Disruption of 1843 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

In 1834, the

In 1834, the

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led by

On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led by  Perhaps a third of the evangelicals, the "middle party", remained within the established church – wishing to preserve its unity. However, for those who left, the issue was clear. It was not the democratising of the church (although concern with power for ordinary people was a movement sweeping Europe at the time), but whether the Church was sovereign within its own domain. The body of the church reflecting Jesus Christ, not the monarch nor Parliament, was to be its head. The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the

Perhaps a third of the evangelicals, the "middle party", remained within the established church – wishing to preserve its unity. However, for those who left, the issue was clear. It was not the democratising of the church (although concern with power for ordinary people was a movement sweeping Europe at the time), but whether the Church was sovereign within its own domain. The body of the church reflecting Jesus Christ, not the monarch nor Parliament, was to be its head. The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the  There was also the issue of needing to train its clergy, resulting in the establishment of New College, with Chalmers appointed as its first principal. It was founded as an institution to educate future ministers and the Scottish leadership, who would in turn guide the moral and religious lives of the Scottish people. New College opened its doors to 168 students in November 1843, including about 100 students who had begun their theological studies before the Disruption.

Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

There was also the issue of needing to train its clergy, resulting in the establishment of New College, with Chalmers appointed as its first principal. It was founded as an institution to educate future ministers and the Scottish leadership, who would in turn guide the moral and religious lives of the Scottish people. New College opened its doors to 168 students in November 1843, including about 100 students who had begun their theological studies before the Disruption.

Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450

The Disruption of 1843, also known as the Great Disruption, was a schism in 1843 in which 450 evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

ministers broke away from the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Reformation of 1560, when it split from the Catholic Church ...

to form the Free Church of Scotland.

The main conflict was over whether the Church of Scotland or the British Government had the power to control clerical positions and benefits. The Disruption came at the end of a bitter conflict within the Church of Scotland, and had major effects in the church and upon Scottish civic life.

The patronage issue

"The Church of Scotland was recognised by Acts of the Parliament as thenational church

A national church is a Christian church associated with a specific ethnic group or nation state. The idea was notably discussed during the 19th century, during the emergence of modern nationalism.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a draft discussing ...

of the Scottish people". Particularly under John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

and later Andrew Melville, the Church of Scotland had always claimed an inherent right to exercise independent spiritual jurisdiction over its own affairs. To some extent, this right was recognised by the Claim of Right of 1689, which ended royal and parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

interference in the order and worship of the church. It was ratified by the Act of Union in 1707.

On the other hand, the right of patronage, in which the patron of a parish had the right to install a minister of his choice, became a point of contention. Many church members believed that this right infringed on the spiritual independence of the church. Others felt that this right was a property of the state. As early as 1712 the right of patronage had been restored in Scotland, amid remonstrances from the church. For many years afterwards, the church's General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of pres ...

tried to reform this practice. However the dominant Moderate Party

The Moderate Party ( sv, Moderata samlingspartiet , ; M), commonly referred to as the Moderates ( ), is a liberal-conservative political party in Sweden. The party generally supports tax cuts, the free market, civil liberties and economic ...

in the church blocked reform out of fear of conflict with the British Government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_est ...

.

The "Ten Years' Conflict"

Veto Act

In 1834, the

In 1834, the evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual expe ...

party attained a majority in the General Assembly for the first time in 100 years. One of their actions was to pass the Veto Act, which gave parishioners the right to reject a minister nominated by their patron. The Veto Act was to prevent the intrusion of ministers on unwilling parishioners, and to restore the importance of the congregational "call". However, it served to polarise positions in the church, and set it on a collision course with the government.

The first test of the Veto Act came with the ''Auchterarder'' case of 1834. The parish of Auchterarder

Auchterarder (; gd, Uachdar Àrdair, meaning Upper Highland) is a small town located north of the Ochil Hills in Perth and Kinross, Scotland, and home to the Gleneagles Hotel. The High Street of Auchterarder gave the town its popular name of "T ...

unanimously rejected the patron's nominee – and the Presbytery refused to proceed with his ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform ...

and induction. The nominee, Robert Young, appealed to the Court of Session

The Court of Session is the supreme civil court of Scotland and constitutes part of the College of Justice; the supreme criminal court of Scotland is the High Court of Justiciary. The Court of Session sits in Parliament House in Edinburg ...

. In 1838, by an 8–5 majority, the court held that in passing the Veto Act, the church had acted '' ultra vires'', and had infringed the statutory rights of patrons. It also ruled Church of Scotland was a creation of the state and derived its legitimacy from act of Parliament

Acts of Parliament, sometimes referred to as primary legislation, are texts of law passed by the legislative body of a jurisdiction (often a parliament or council). In most countries with a parliamentary system of government, acts of parliame ...

.

The'' Auchterarder'' ruling contradicted the Scottish church's Confession of Faith

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) in a form which is structured by subjects which summarize its core tenets.

The ea ...

. As Burleigh puts it: "The notion of the Church as an independent community governed by its own officers and capable of entering into a compact with the state was repudiated" (p. 342). An appeal to the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

was rejected.

Further conflicts

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of

In a second case, the Court of Session summoned the Presbytery of Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, sco, Dunkell, from gd, Dùn Chailleann, "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to t ...

for proceeding with an ordination despite a court interdict. In 1839, the General Assembly suspended seven ministers from Strathbogie for proceeding with an induction in Marnoch in defiance of its orders. In 1841, the seven Strathbogie ministers were deposed for acknowledging the superiority of the secular court in spiritual matters.

The evangelical party later presented to parliament a ''Claim, Declaration and Protest Anent the Encroachments of the Court of Session''. The claim recognised the jurisdiction of the civil courts over the endowments that the government gave to the Scottish church. This "The Claim of Right" was drawn up by Alexander Murray Dunlop

Alexander Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop (27 December 1798 – 1 September 1870) was a Scottish church advocate and Liberal Party politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Greenock from 1852 to 1868. He was a very influential fi ...

. However, the claim resolved that the church give up these endowments rather than see the 'Crown Rights of the Redeemer' (i.e. the spiritual independence of the church) compromised. This claim was rejected by parliament in January 1843, leading to the Disruption in May.

The Disruption

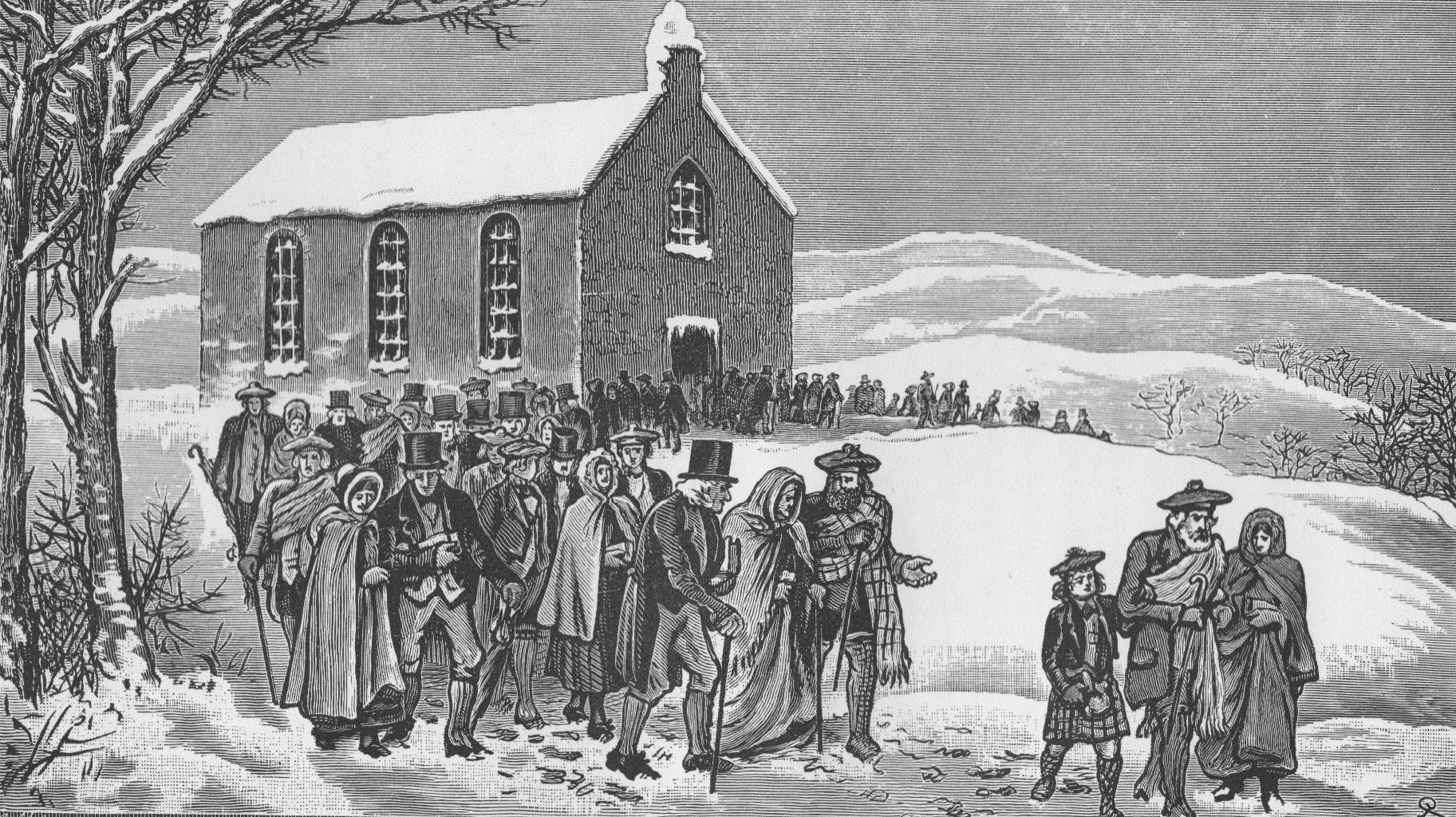

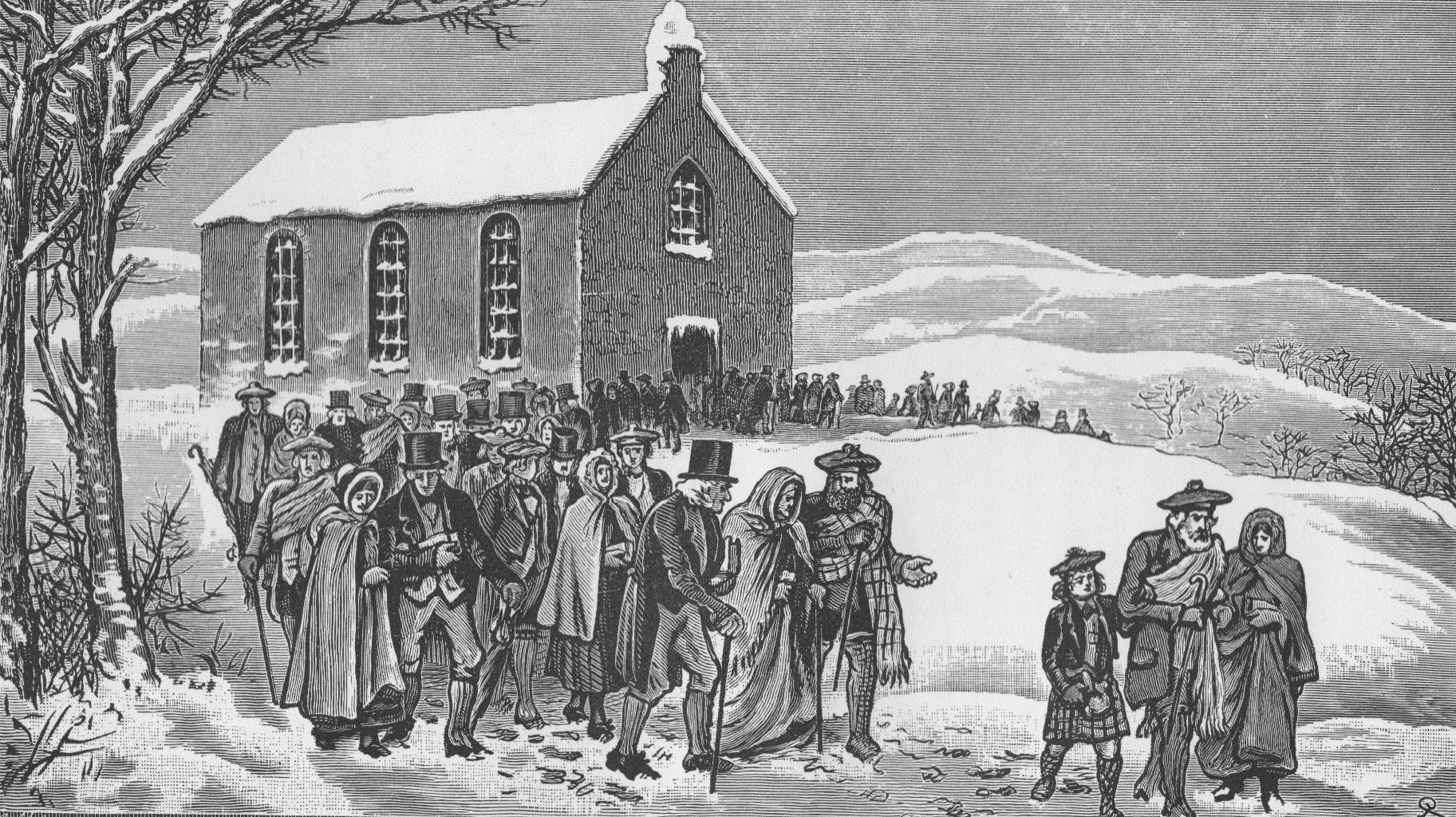

On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led by

On 18 May 1843, 121 ministers and 73 elders led by David Welsh

David Welsh FRSE (11 December 179324 April 1845) was a Scottish divine and academic. He was Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1842. In the Disruption of 1843 he was one of the leading figures in the establishmen ...

met at the Church of St Andrew in George Street, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. After Welsh read a Protest, the group left St. Andrews and walked down the hill to the Tanfield Hall at Canonmills. There they held the first meeting of the Free Church of Scotland, the Disruption Assembly. Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

was appointed the first Moderator. On 23 May , a second meeting was held for the signing of the Act of Separation by the ministers. Eventually, 474 of about 1,200 ministers left the Church of Scotland for the Free Church.

In leaving the established church, however, they did not reject the principle of establishment. As Chalmers declared: "Though we quit the Establishment, we go out on the Establishment principle; we quit a vitiated Establishment but would rejoice in returning to a pure one. We are advocates for a national recognition of religion – and we are not voluntaries."

Perhaps a third of the evangelicals, the "middle party", remained within the established church – wishing to preserve its unity. However, for those who left, the issue was clear. It was not the democratising of the church (although concern with power for ordinary people was a movement sweeping Europe at the time), but whether the Church was sovereign within its own domain. The body of the church reflecting Jesus Christ, not the monarch nor Parliament, was to be its head. The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the

Perhaps a third of the evangelicals, the "middle party", remained within the established church – wishing to preserve its unity. However, for those who left, the issue was clear. It was not the democratising of the church (although concern with power for ordinary people was a movement sweeping Europe at the time), but whether the Church was sovereign within its own domain. The body of the church reflecting Jesus Christ, not the monarch nor Parliament, was to be its head. The Disruption was basically a spiritual phenomenon – and for its proponents it stood in a direct line with the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

and the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' The Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on the church ...

s.

Splitting the church had major implications. Those who left forfeited livings, manses and pulpits, and had, without the aid of the establishment, to found and finance a national church from scratch. This was done with remarkable energy, zeal and sacrifice. Another implication was that the church they left was more tolerant of a wider range of doctrinal views.

There was also the issue of needing to train its clergy, resulting in the establishment of New College, with Chalmers appointed as its first principal. It was founded as an institution to educate future ministers and the Scottish leadership, who would in turn guide the moral and religious lives of the Scottish people. New College opened its doors to 168 students in November 1843, including about 100 students who had begun their theological studies before the Disruption.

Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

There was also the issue of needing to train its clergy, resulting in the establishment of New College, with Chalmers appointed as its first principal. It was founded as an institution to educate future ministers and the Scottish leadership, who would in turn guide the moral and religious lives of the Scottish people. New College opened its doors to 168 students in November 1843, including about 100 students who had begun their theological studies before the Disruption.

Most of the principles on which the protestors went out were conceded by Parliament by 1929, clearing the way for the re-union of that year, but the Church of Scotland never fully regained its position after the division.

Photographic portraiture

The painterDavid Octavius Hill

David Octavius Hill (20 May 1802 – 17 May 1870) was a Scottish painter, photographer and arts activist. He formed Hill & Adamson studio with the engineer and photographer Robert Adamson between 1843 and 1847 to pioneer many aspects of ph ...

was present at the Disruption Assembly and decided to record the scene. He received encouragement from another spectator, the physicist Sir David Brewster who suggested using the new invention, photography, to get likenesses of all the ministers present, and introduced Hill to the photographer Robert Adamson. Subsequently, a series of photographs were taken of those who had been present, and the 5-foot x 11-foot 4 inches (1.53 m x 3.45 m) painting was eventually completed in 1866. The partnership that developed between Hill and Adamson pioneered the art of photography in Scotland. The painting predominantly features the ministers involved in the Disruption but Hill also included many other men – and some women – who were involved in the establishment of the Free Church. The painting depicts 457 people of the 1500 or so who were present at the assembly on 23 May 1843.

See also

* History of Scotland * Religion in the United KingdomReferences

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Cameron, N. ''et al.'' (eds.) ''Dictionary of Scottish Church History and Theology'', Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1993. * Burleigh, J. H. S. ''A Church History of Scotland'' Edinburgh: Hope Trust 1988. {{Nineteenth-century Scotland History of the Church of Scotland Presbyterianism in Scotland Schisms in Christianity 1843 in Scotland 19th-century Calvinism 1843 in Christianity Church of Scotland