Digestive System on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The human digestive system consists of the

There are several organs and other components involved in the digestion of food. The organs known as the accessory digestive organs are the

There are several organs and other components involved in the digestion of food. The organs known as the accessory digestive organs are the

The

The

There are three pairs of main

There are three pairs of main

Food enters the mouth where the first stage in the digestive process takes place, with the action of the

Food enters the mouth where the first stage in the digestive process takes place, with the action of the

The

The

The

The

The

The

The

The

Partially digested food starts to arrive in the

Partially digested food starts to arrive in the

gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

plus the accessory organs of digestion (the tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered by taste ...

, salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary ...

s, pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an ...

, liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

, and gallbladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

). Digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

involves the breakdown of food into smaller and smaller components, until they can be absorbed and assimilated into the body. The process of digestion has three stages: the cephalic phase, the gastric phase, and the intestinal phase

The nervous system, and endocrine system collaborate in the digestive system to control gastric secretions, and motility associated with the movement of food throughout the gastrointestinal tract, including peristalsis, and segmentation contraction ...

.

The first stage, the cephalic phase of digestion, begins with secretions from gastric glands in response to the sight and smell of food. This stage includes the mechanical breakdown of food by chewing

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by teeth. It is the first step of digestion, and it increases the surface area of foods to allow a more efficient break down by enzymes. During the mastication process, th ...

, and the chemical breakdown by digestive enzyme

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

s, that takes place in the mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

. Saliva

Saliva (commonly referred to as spit) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which DNA can ...

contains the digestive enzymes amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large amounts of ...

, and lingual lipase, secreted by the salivary and serous glands on the tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered by taste ...

. Chewing, in which the food is mixed with saliva, begins the mechanical process of digestion. This produces a bolus which is swallowed down the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

to enter the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

.

The second stage of digestion begins in the stomach with the gastric phase. Here the food is further broken down by mixing with gastric acid

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the ...

until it passes into the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine m ...

, the first part of the small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

.

The third stage begins in the duodenum with the intestinal phase, where partially digested food is mixed with a number of enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

s produced by the pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an ...

. Digestion is helped by the chewing of food carried out by the muscles of mastication

There are four classical muscles of mastication. During mastication, three muscles of mastication (''musculi masticatorii'') are responsible for adduction of the jaw, and one (the lateral pterygoid) helps to abduct it. All four move the jaw lat ...

, the tongue, and the teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

, and also by the contractions of peristalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, whi ...

, and segmentation. Gastric acid

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the ...

, and the production of mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

in the stomach, are essential for the continuation of digestion.

Peristalsis is the rhythmic contraction of muscle

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of mus ...

s that begins in the esophagus and continues along the wall of the stomach and the rest of the gastrointestinal tract. This initially results in the production of chyme

Chyme or chymus (; from Greek χυμός ''khymos'', "juice") is the semi-fluid mass of partly digested food that is expelled by a person's stomach, through the pyloric valve, into the duodenumchyle

Chyle (from the Greek word χυλός ''chylos'', "juice") is a milky bodily fluid consisting of lymph and emulsified fats, or free fatty acids (FFAs). It is formed in the small intestine during digestion of fatty foods, and taken up by lymph ...

into the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid ...

. Most of the digestion of food takes place in the small intestine. Water and some minerals

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid chemical compound with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.John P. Rafferty, ed ...

are reabsorbed back into the blood in the colon of the large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

. The waste products of digestion (feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a rela ...

) are defecated

Defecation (or defaecation) follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus. The act has a variety of names ranging fro ...

from the rectum

The rectum is the final straight portion of the large intestine in humans and some other mammals, and the gut in others. The adult human rectum is about long, and begins at the rectosigmoid junction (the end of the sigmoid colon) at the l ...

via the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, ...

.

Components

There are several organs and other components involved in the digestion of food. The organs known as the accessory digestive organs are the

There are several organs and other components involved in the digestion of food. The organs known as the accessory digestive organs are the liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

, gall bladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

and pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an ...

. Other components include the mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

, salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary ...

s, tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered by taste ...

, teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

and epiglottis

The epiglottis is a leaf-shaped flap in the throat that prevents food and water from entering the trachea and the lungs. It stays open during breathing, allowing air into the larynx. During swallowing, it closes to prevent aspiration of food in ...

.

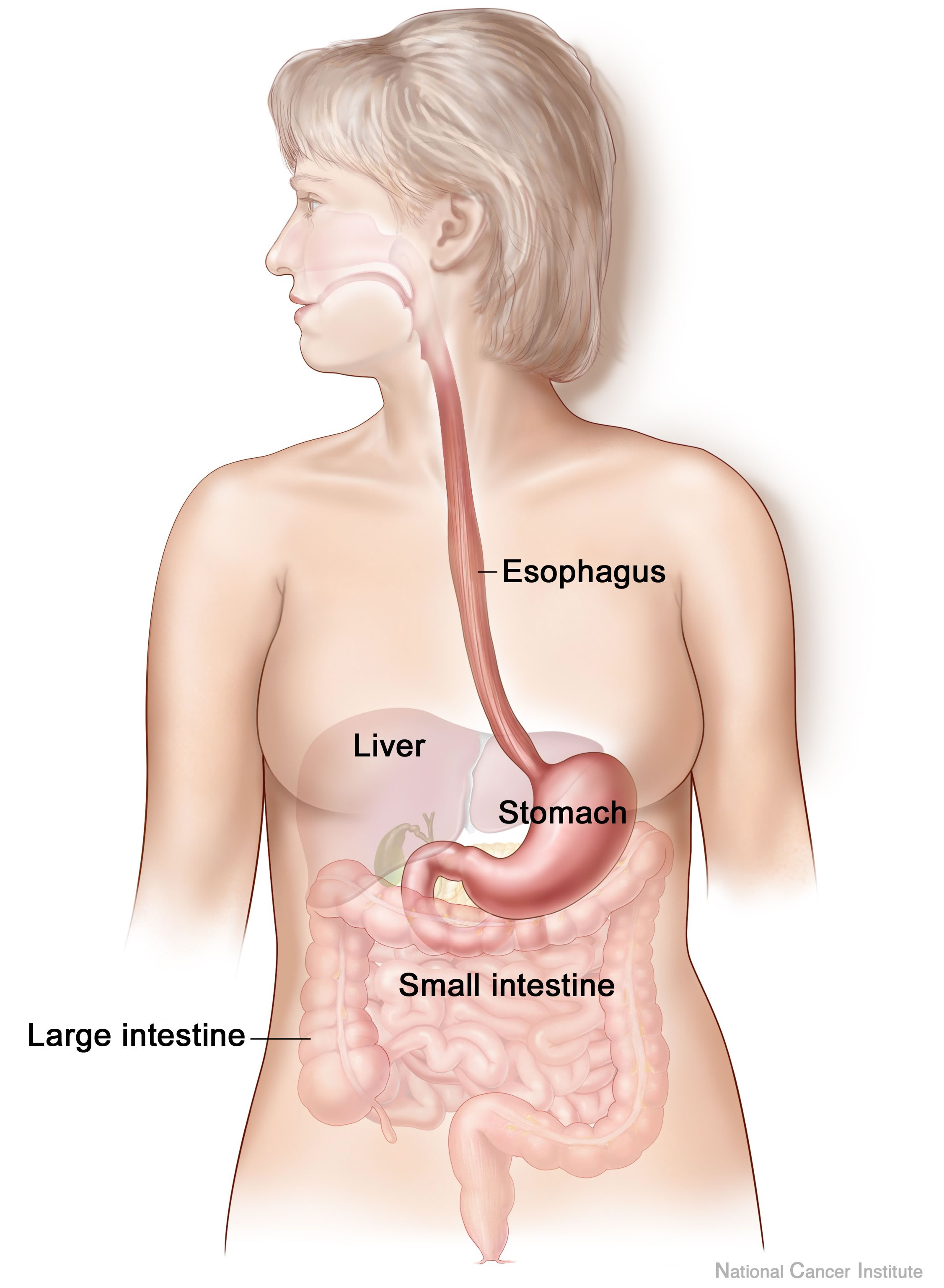

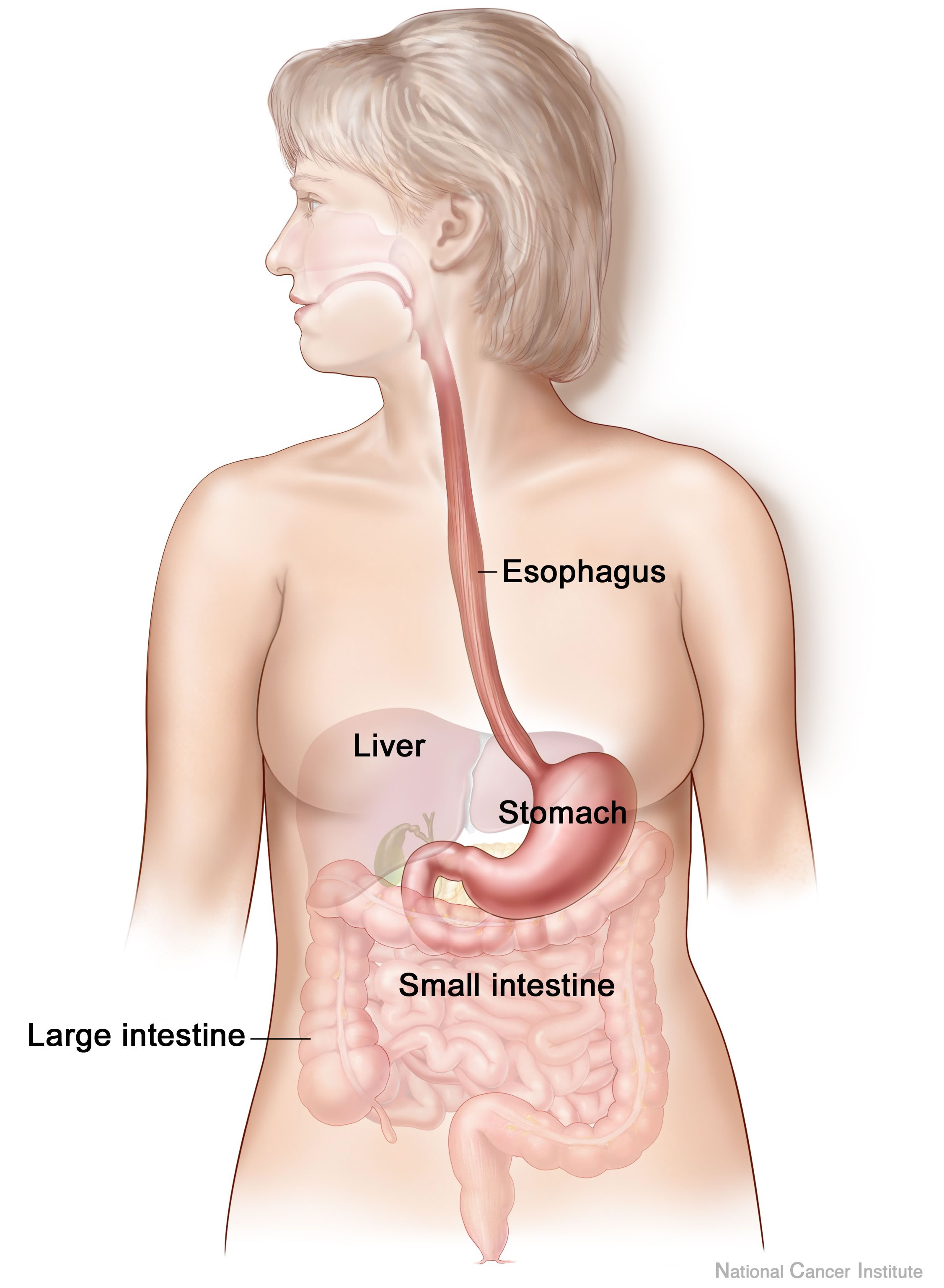

The largest structure of the digestive system

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and express ...

is the gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans and ...

(GI tract). This starts at the mouth and ends at the anus

The anus (Latin, 'ring' or 'circle') is an opening at the opposite end of an animal's digestive tract from the mouth. Its function is to control the expulsion of feces, the residual semi-solid waste that remains after food digestion, which, ...

, covering a distance of about nine metres.

A major digestive organ is the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

. Within its mucosa

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

are millions of embedded gastric glands

The gastric glands are glands in the lining of the stomach that play an essential role in the process of digestion. All of the glands have mucus-secreting foveolar cells. Mucus lines the entire stomach, and protects the stomach lining from the ...

. Their secretions are vital to the functioning of the organ.

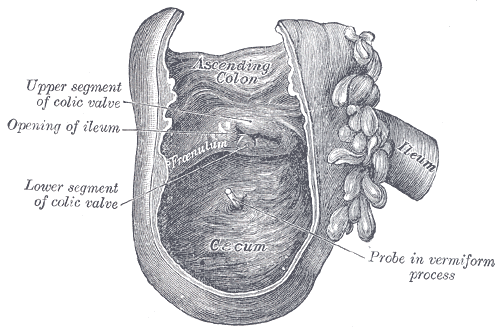

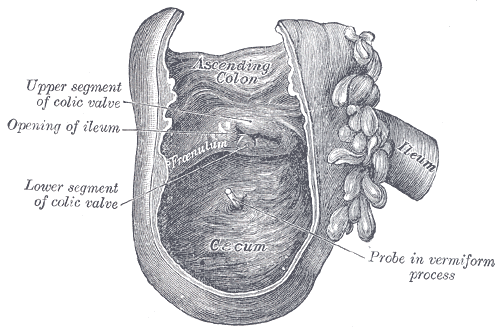

Most of the digestion of food takes place in the small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ (anatomy), organ in the human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract where most of the #Absorption, absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intes ...

which is the longest part of the GI tract.

The largest part of the GI tract is the colon or large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before bein ...

. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste matter is stored prior to defecation

Defecation (or defaecation) follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus. The act has a variety of names ranging f ...

.

There are many specialised cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

of the GI tract. These include the various cells of the gastric glands, taste cells, pancreatic duct cell

Centroacinar cells are spindle-shaped cells in the exocrine pancreas. They represent an extension of the intercalated duct into each pancreatic acinus. These cells are commonly known as duct cells, and secrete an aqueous bicarbonate solution und ...

s, enterocyte

Enterocytes, or intestinal absorptive cells, are simple columnar epithelial cells which line the inner surface of the small and large intestines. A glycocalyx surface coat contains digestive enzymes. Microvilli on the apical surface increase i ...

s and microfold cells.

Some parts of the digestive system are also part of the excretory system

The excretory system is a passive biological system that removes excess, unnecessary materials from the body fluids of an organism, so as to help maintain internal chemical homeostasis and prevent damage to the body. The dual function of excreto ...

, including the large intestine.

Mouth

The

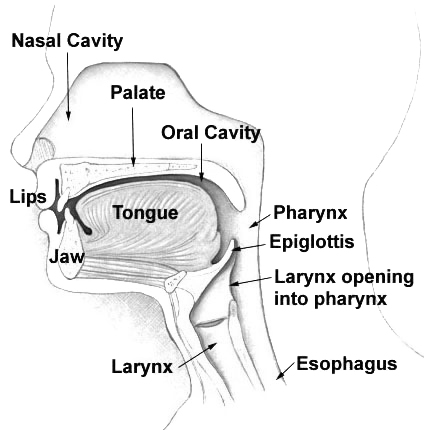

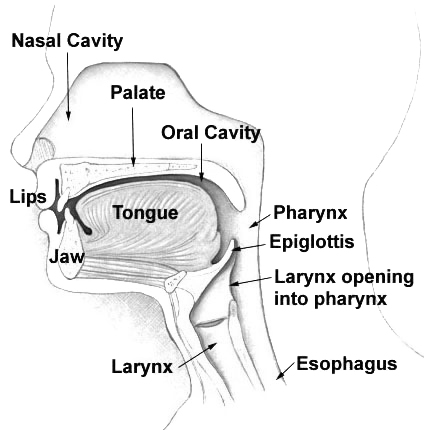

The mouth

In animal anatomy, the mouth, also known as the oral cavity, or in Latin cavum oris, is the opening through which many animals take in food and issue vocal sounds. It is also the cavity lying at the upper end of the alimentary canal, bounded on ...

is the first part of the upper gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans an ...

and is equipped with several structures that begin the first processes of digestion. These include salivary glands, teeth and the tongue. The mouth consists of two regions; the vestibule and the oral cavity proper. The vestibule is the area between the teeth, lips and cheeks, and the rest is the oral cavity proper. Most of the oral cavity is lined with oral mucosa

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. It comprises stratified squamous epithelium, termed "oral epithelium", and an underlying connective tissue termed '' lamina propria''. The oral cavity has sometimes been de ...

, a mucous membrane

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It i ...

that produces a lubricating mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

, of which only a small amount is needed. Mucous membranes vary in structure in the different regions of the body but they all produce a lubricating mucus, which is either secreted by surface cells or more usually by underlying glands. The mucous membrane in the mouth continues as the thin mucosa which lines the bases of the teeth. The main component of mucus is a glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glyco ...

called mucin

Mucins () are a family of high molecular weight, heavily glycosylated proteins (glycoconjugates) produced by epithelial tissues in most animals. Mucins' key characteristic is their ability to form gels; therefore they are a key component in most ...

and the type secreted varies according to the region involved. Mucin is viscous, clear, and clinging. Underlying the mucous membrane in the mouth is a thin layer of smooth muscle tissue

Smooth muscle is an involuntary non- striated muscle, so-called because it has no sarcomeres and therefore no striations (''bands'' or ''stripes''). It is divided into two subgroups, single-unit and multiunit smooth muscle. Within single-unit ...

and the loose connection to the membrane gives it its great elasticity. It covers the cheeks, inner surfaces of the lip

The lips are the visible body part at the mouth of many animals, including humans. Lips are soft, movable, and serve as the opening for food intake and in the articulation of sound and speech. Human lips are a tactile sensory organ, and can be ...

s, and floor of the mouth, and the mucin produced is highly protective against tooth decay

Tooth decay, also known as cavities or caries, is the breakdown of teeth due to acids produced by bacteria. The cavities may be a number of different colors from yellow to black. Symptoms may include pain and difficulty with eating. Complicatio ...

.

The roof of the mouth is termed the palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly separ ...

and it separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity. The palate is hard at the front of the mouth since the overlying mucosa is covering a plate of bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, ...

; it is softer and more pliable at the back being made of muscle and connective tissue, and it can move to swallow food and liquids. The soft palate

The soft palate (also known as the velum, palatal velum, or muscular palate) is, in mammals, the soft tissue constituting the back of the roof of the mouth. The soft palate is part of the palate of the mouth; the other part is the hard palat ...

ends at the uvula

The palatine uvula, usually referred to as simply the uvula, is a conic projection from the back edge of the middle of the soft palate, composed of connective tissue containing a number of racemose glands, and some muscular fibers. It also conta ...

. The surface of the hard palate

The hard palate is a thin horizontal bony plate made up of two bones of the facial skeleton, located in the roof of the mouth. The bones are the palatine process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of palatine bone. The hard palate spans t ...

allows for the pressure needed in eating food, to leave the nasal passage clear. The opening between the lips is termed the oral fissure, and the opening into the throat is called the fauces.

At either side of the soft palate are the palatoglossus muscle

The palatoglossus or palatoglossal muscle is a muscle of the soft palate and extrinsic muscle of the tongue. Its surface is covered by oral mucosa and forms the visible palatoglossal arch.

Structure

Palatoglossus arises from the palatine aponeur ...

s which also reach into regions of the tongue. These muscles raise the back of the tongue and also close both sides of the fauces to enable food to be swallowed. Mucus helps in the mastication of food in its ability to soften and collect the food in the formation of the bolus.

Salivary glands

There are three pairs of main

There are three pairs of main salivary gland

The salivary glands in mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of minor salivary glands. Salivary ...

s and between 800 and 1,000 minor salivary glands, all of which mainly serve the digestive process, and also play an important role in the maintenance of dental health and general mouth lubrication, without which speech would be impossible. The main glands are all exocrine gland

Exocrine glands are glands that secrete substances on to an epithelial surface by way of a duct. Examples of exocrine glands include sweat, salivary, mammary, ceruminous, lacrimal, sebaceous, prostate and mucous. Exocrine glands are one ...

s, secreting via ducts. All of these glands terminate in the mouth. The largest of these are the parotid gland

The parotid gland is a major salivary gland in many animals. In humans, the two parotid glands are present on either side of the mouth and in front of both ears. They are the largest of the salivary glands. Each parotid is wrapped around the ma ...

s—their secretion is mainly serous

In physiology, serous fluid or serosal fluid (originating from the Medieval Latin word ''serosus'', from Latin ''serum'') is any of various body fluids resembling serum, that are typically pale yellow or transparent and of a benign nature. The fl ...

. The next pair are underneath the jaw, the submandibular gland

The paired submandibular glands (historically known as submaxillary glands) are major salivary glands located beneath the floor of the mouth. They each weigh about 15 grams and contribute some 60–67% of unstimulated saliva secretion; on stimul ...

s, these produce both serous fluid

In physiology, serous fluid or serosal fluid (originating from the Medieval Latin word ''serosus'', from Latin ''serum'') is any of various body fluids resembling serum, that are typically pale yellow or transparent and of a benign nature. The fl ...

and mucus

Mucus ( ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both serous and mucous cells. It ...

. The serous fluid is produced by serous gland

Serous glands secrete serous fluid. They contain serous acini, a grouping of serous cells that secrete serous fluid, isotonic with blood plasma, that contains enzymes such as alpha-amylase.

Serous glands are most common in the parotid gland and ...

s in these salivary glands which also produce lingual lipase. They produce about 70% of the oral cavity saliva. The third pair are the sublingual gland

The paired sublingual glands are major salivary glands in the mouth. They are the smallest, most diffuse, and the only unencapsulated major salivary glands. They provide only 3-5% of the total salivary volume. There are also two other types of s ...

s located underneath the tongue and their secretion is mainly mucous with a small percentage of saliva.

Within the oral mucosa

The oral mucosa is the mucous membrane lining the inside of the mouth. It comprises stratified squamous epithelium, termed "oral epithelium", and an underlying connective tissue termed '' lamina propria''. The oral cavity has sometimes been de ...

, and also on the tongue, palates, and floor of the mouth, are the minor salivary glands; their secretions are mainly mucous and they are innervated by the facial nerve

The facial nerve, also known as the seventh cranial nerve, cranial nerve VII, or simply CN VII, is a cranial nerve that emerges from the pons of the brainstem, controls the muscles of facial expression, and functions in the conveyance of taste ...

( CN7).Illustrated Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Fehrenbach and Herring, Elsevier, 2012, p. 157 The glands also secrete amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large amounts of ...

a first stage in the breakdown of food acting on the carbohydrate in the food to transform the starch content into maltose. There are other serous gland

Serous glands secrete serous fluid. They contain serous acini, a grouping of serous cells that secrete serous fluid, isotonic with blood plasma, that contains enzymes such as alpha-amylase.

Serous glands are most common in the parotid gland and ...

s on the surface of the tongue that encircle taste bud

Taste buds contain the taste receptor cells, which are also known as gustatory cells. The taste receptors are located around the small structures known as papillae found on the upper surface of the tongue, soft palate, upper esophagus, the c ...

s on the back part of the tongue and these also produce lingual lipase. Lipase

Lipase ( ) is a family of enzymes that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats. Some lipases display broad substrate scope including esters of cholesterol, phospholipids, and of lipid-soluble vitamins and sphingomyelinases; however, these are usually ...

is a digestive enzyme

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

that catalyses the hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water is the nucleophile.

Biological hydrolysi ...

of lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

s (fats). These glands are termed Von Ebner's glands which have also been shown to have another function in the secretion of histatins which offer an early defense (outside of the immune system) against microbes in food, when it makes contact with these glands on the tongue tissue. Sensory information can stimulate the secretion of saliva providing the necessary fluid for the tongue to work with and also to ease swallowing of the food.

=Saliva

=Saliva

Saliva (commonly referred to as spit) is an extracellular fluid produced and secreted by salivary glands in the mouth. In humans, saliva is around 99% water, plus electrolytes, mucus, white blood cells, epithelial cells (from which DNA can ...

moistens and softens food, and along with the chewing action of the teeth, transforms the food into a smooth bolus. The bolus is further helped by the lubrication provided by the saliva in its passage from the mouth into the esophagus. Also of importance is the presence in saliva of the digestive enzymes amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large amounts of ...

and lipase

Lipase ( ) is a family of enzymes that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats. Some lipases display broad substrate scope including esters of cholesterol, phospholipids, and of lipid-soluble vitamins and sphingomyelinases; however, these are usually ...

. Amylase starts to work on the starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human die ...

in carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

s, breaking it down into the simple sugars

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or double ...

of maltose

}

Maltose ( or ), also known as maltobiose or malt sugar, is a disaccharide formed from two units of glucose joined with an α(1→4) bond. In the isomer isomaltose, the two glucose molecules are joined with an α(1→6) bond. Maltose is the tw ...

and dextrose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, usin ...

that can be further broken down in the small intestine. Saliva in the mouth can account for 30% of this initial starch digestion. Lipase starts to work on breaking down fats. Lipase is further produced in the pancreas

The pancreas is an organ of the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a gland. The pancreas is a mixed or heterocrine gland, i.e. it has both an ...

where it is released to continue this digestion of fats. The presence of salivary lipase is of prime importance in young babies whose pancreatic lipase has yet to be developed.

As well as its role in supplying digestive enzyme

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

s, saliva has a cleansing action for the teeth and mouth. It also has an immunological

Immunology is a branch of medicineImmunology for Medical Students, Roderick Nairn, Matthew Helbert, Mosby, 2007 and biology that covers the medical study of immune systems in humans, animals, plants and sapient species. In such we can see the ...

role in supplying antibodies to the system, such as immunoglobulin A

Immunoglobulin A (Ig A, also referred to as sIgA in its secretory form) is an antibody that plays a role in the immune function of mucous membranes. The amount of IgA produced in association with mucosal membranes is greater than all other typ ...

. This is seen to be key in preventing infection

An infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable di ...

s of the salivary glands, importantly that of parotitis.

Saliva also contains a glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glyco ...

called haptocorrin which is a binding protein to vitamin B12. It binds with the vitamin in order to carry it safely through the acidic content of the stomach. When it reaches the duodenum, pancreatic enzymes break down the glycoprotein and free the vitamin which then binds with intrinsic factor.

Tongue

Food enters the mouth where the first stage in the digestive process takes place, with the action of the

Food enters the mouth where the first stage in the digestive process takes place, with the action of the tongue

The tongue is a muscular organ in the mouth of a typical tetrapod. It manipulates food for mastication and swallowing as part of the digestive process, and is the primary organ of taste. The tongue's upper surface (dorsum) is covered by taste ...

and the secretion of saliva. The tongue is a fleshy and muscular

Skeletal muscles (commonly referred to as muscles) are organs of the vertebrate muscular system and typically are attached by tendons to bones of a skeleton. The muscle cells of skeletal muscles are much longer than in the other types of muscle ...

sensory organ

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the world through the detection of stimuli. (For example, in the human body, the brain which is part of the central nervous system re ...

, and the first sensory information is received via the taste buds in the papillae on its surface. If the taste is agreeable, the tongue will go into action, manipulating the food in the mouth which stimulates the secretion of saliva from the salivary glands. The liquid quality of the saliva will help in the softening of the food and its enzyme content will start to break down the food whilst it is still in the mouth. The first part of the food to be broken down is the starch of carbohydrates (by the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products ...

amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large amounts of ...

in the saliva).

The tongue is attached to the floor of the mouth by a ligamentous band called the frenum and this gives it great mobility for the manipulation of food (and speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

); the range of manipulation is optimally controlled by the action of several muscles and limited in its external range by the stretch of the frenum. The tongue's two sets of muscles, are four intrinsic muscles

Anatomical terminology is used to uniquely describe aspects of skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle such as their actions, structure, size, and location.

Types

There are three types of muscle tissue in the body: skeletal, smooth ...

that originate in the tongue and are involved with its shaping, and four extrinsic muscles originating in bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, ...

that are involved with its movement.

=Taste

=

Taste

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste (flavor). Taste is the perception produced or stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste receptor ...

is a form of chemoreception that takes place in the specialised taste receptor

A taste receptor or tastant is a type of cellular receptor which facilitates the sensation of taste. When food or other substances enter the mouth, molecules interact with saliva and are bound to taste receptors in the oral cavity and other loc ...

s, contained in structures called taste buds

Taste buds contain the taste receptor cells, which are also known as gustatory cells. The taste receptors are located around the small structures known as papillae found on the upper surface of the tongue, soft palate, upper esophagus, the che ...

in the mouth. Taste buds are mainly on the upper surface (dorsum) of the tongue. The function of taste perception is vital to help prevent harmful or rotten foods from being consumed. There are also taste buds on the epiglottis

The epiglottis is a leaf-shaped flap in the throat that prevents food and water from entering the trachea and the lungs. It stays open during breathing, allowing air into the larynx. During swallowing, it closes to prevent aspiration of food in ...

and upper part of the esophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

. The taste buds are innervated by a branch of the facial nerve the chorda tympani

The chorda tympani is a branch of the facial nerve that originates from the taste buds in the front of the tongue, runs through the middle ear, and carries taste messages to the brain. It joins the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII) inside the fa ...

, and the glossopharyngeal nerve

The glossopharyngeal nerve (), also known as the ninth cranial nerve, cranial nerve IX, or simply CN IX, is a cranial nerve that exits the brainstem from the sides of the upper medulla, just anterior (closer to the nose) to the vagus nerve. ...

. Taste messages are sent via these cranial nerves

Cranial nerves are the nerves that emerge directly from the brain (including the brainstem), of which there are conventionally considered twelve pairs. Cranial nerves relay information between the brain and parts of the body, primarily to and f ...

to the brain

A brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as Visual perception, vision. I ...

. The brain can distinguish between the chemical qualities of the food. The five basic tastes are referred to as those of saltiness

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste (flavor). Taste is the perception produced or stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste receptor ...

, sourness, bitterness, sweetness

Sweetness is a basic taste most commonly perceived when eating foods rich in sugars. Sweet tastes are generally regarded as pleasurable. In addition to sugars like sucrose, many other chemical compounds are sweet, including aldehydes, ketone ...

, and umami

Umami ( from ja, 旨味 ), or savoriness, is one of the five basic tastes. It has been described as savory and is characteristic of broths and cooked meats.

People taste umami through taste receptors that typically respond to glutamates and ...

. The detection of saltiness and sourness enables the control of salt and acid balance. The detection of bitterness warns of poisons—many of a plant's defences are of poisonous compounds that are bitter. Sweetness guides to those foods that will supply energy; the initial breakdown of the energy-giving carbohydrates by salivary amylase creates the taste of sweetness since simple sugars are the first result. The taste of umami is thought to signal protein-rich food. Sour tastes are acidic which is often found in bad food. The brain has to decide very quickly whether the food should be eaten or not. It was the findings in 1991, describing the first olfactory

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

receptors that helped to prompt the research into taste. The olfactory receptors are located on cell surfaces in the nose

A nose is a protuberance in vertebrates that houses the nostrils, or nares, which receive and expel air for respiration alongside the mouth. Behind the nose are the olfactory mucosa and the sinuses. Behind the nasal cavity, air next passe ...

which bind to chemicals enabling the detection of smells. It is assumed that signals from taste receptors work together with those from the nose, to form an idea of complex food flavours.

Teeth

Teeth

A tooth ( : teeth) is a hard, calcified structure found in the jaws (or mouths) of many vertebrates and used to break down food. Some animals, particularly carnivores and omnivores, also use teeth to help with capturing or wounding prey, ...

are complex structures made of materials specific to them. They are made of a bone-like material called dentin

Dentin () (American English) or dentine ( or ) (British English) ( la, substantia eburnea) is a calcified tissue of the body and, along with enamel, cementum, and pulp, is one of the four major components of teeth. It is usually covered by e ...

, which is covered by the hardest tissue in the body— enamel. Teeth have different shapes to deal with different aspects of mastication

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by teeth. It is the first step of digestion, and it increases the surface area of foods to allow a more efficient break down by enzymes. During the mastication process, ...

employed in tearing and chewing pieces of food into smaller and smaller pieces. This results in a much larger surface area for the action of digestive enzymes.

The teeth are named after their particular roles in the process of mastication—incisors

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

are used for cutting or biting off pieces of food; canines, are used for tearing, premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

and molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

are used for chewing and grinding. Mastication of the food with the help of saliva and mucus results in the formation of a soft bolus which can then be swallowed to make its way down the upper gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The GI tract contains all the major organs of the digestive system, in humans an ...

to the stomach.

The digestive enzymes in saliva also help in keeping the teeth clean by breaking down any lodged food particles.

Epiglottis

The

The epiglottis

The epiglottis is a leaf-shaped flap in the throat that prevents food and water from entering the trachea and the lungs. It stays open during breathing, allowing air into the larynx. During swallowing, it closes to prevent aspiration of food in ...

is a flap of elastic cartilage

Elastic cartilage, fibroelastic cartilage or yellow fibrocartilage is a type of cartilage present in the pinnae (auricles) of the ear giving it shape, provides shape for the lateral region of the external auditory meatus, medial part of the aud ...

attached to the entrance of the larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

. It is covered with a mucous membrane and there are taste buds on its lingual surface which faces into the mouth. Its laryngeal surface faces into the larynx. The epiglottis functions to guard the entrance of the glottis

The glottis is the opening between the vocal folds (the rima glottidis). The glottis is crucial in producing vowels and voiced consonants.

Etymology

From Ancient Greek ''γλωττίς'' (glōttís), derived from ''γλῶττα'' (glôtta), v ...

, the opening between the vocal folds

In humans, vocal cords, also known as vocal folds or voice reeds, are folds of throat tissues that are key in creating sounds through vocalization. The size of vocal cords affects the pitch of voice. Open when breathing and vibrating for speec ...

. It is normally pointed upward during breathing with its underside functioning as part of the pharynx, but during swallowing, the epiglottis folds down to a more horizontal position, with its upper side functioning as part of the pharynx. In this manner it prevents food from going into the trachea and instead directs it to the esophagus, which is behind. During swallowing, the backward motion of the tongue forces the epiglottis over the glottis' opening to prevent any food that is being swallowed from entering the larynx which leads to the lungs; the larynx is also pulled upwards to assist this process. Stimulation of the larynx by ingested matter produces a strong cough reflex in order to protect the lungs.

Pharynx

Thepharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its st ...

is a part of the conducting zone

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of respiration in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory mucosa.

Air is breathed in through the nose to ...

of the respiratory system

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies g ...

and also a part of the digestive system. It is the part of the throat immediately behind the nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal ...

at the back of the mouth and above the esophagus and larynx

The larynx (), commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about ...

. The pharynx is made up of three parts. The lower two parts—the oropharynx

The pharynx (plural: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the oesophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its struc ...

and the laryngopharynx are involved in the digestive system. The laryngopharynx connects to the esophagus and it serves as a passageway for both air and food. Air enters the larynx anteriorly but anything swallowed has priority and the passage of air is temporarily blocked. The pharynx is innervated by the pharyngeal plexus of the vagus nerve. Muscles in the pharynx push the food into the esophagus. The pharynx joins the esophagus at the oesophageal inlet which is located behind the cricoid cartilage

The cricoid cartilage , or simply cricoid (from the Greek ''krikoeides'' meaning "ring-shaped") or cricoid ring, is the only complete ring of cartilage around the trachea. It forms the back part of the voice box and functions as an attachment si ...

.

Esophagus

Theesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to t ...

, commonly known as the foodpipe or gullet, consists of a muscular tube through which food passes from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is continuous with the laryngopharynx. It passes through the posterior mediastinum

The mediastinum (from ) is the central compartment of the thoracic cavity. Surrounded by loose connective tissue, it is an undelineated region that contains a group of structures within the thorax, namely the heart and its vessels, the esopha ...

in the thorax

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the c ...

and enters the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

through a hole in the thoracic diaphragm

The thoracic diaphragm, or simply the diaphragm ( grc, διάφραγμα, diáphragma, partition), is a sheet of internal skeletal muscle in humans and other mammals that extends across the bottom of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm is the m ...

—the esophageal hiatus, at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebra (T10). Its length averages 25 cm, varying with an individual's height. It is divided into cervical, thoracic

The thorax or chest is a part of the anatomy of humans, mammals, and other tetrapod animals located between the neck and the abdomen. In insects, crustaceans, and the extinct trilobites, the thorax is one of the three main divisions of the crea ...

and abdominal

The abdomen (colloquially called the belly, tummy, midriff, tucky or stomach) is the part of the body between the thorax (chest) and pelvis, in humans and in other vertebrates. The abdomen is the front part of the abdominal segment of the to ...

parts. The pharynx joins the esophagus at the esophageal inlet which is behind the cricoid cartilage

The cricoid cartilage , or simply cricoid (from the Greek ''krikoeides'' meaning "ring-shaped") or cricoid ring, is the only complete ring of cartilage around the trachea. It forms the back part of the voice box and functions as an attachment si ...

.

At rest the esophagus is closed at both ends, by the upper and lower esophageal sphincters. The opening of the upper sphincter is triggered by the swallowing reflex

Swallowing, sometimes called deglutition in scientific contexts, is the process in the human or animal body that allows for a substance to pass from the mouth, to the pharynx, and into the esophagus, while shutting the epiglottis. Swallowing is ...

so that food is allowed through. The sphincter also serves to prevent back flow from the esophagus into the pharynx. The esophagus has a mucous membrane and the epithelium which has a protective function is continuously replaced due to the volume of food that passes inside the esophagus. During swallowing, food passes from the mouth through the pharynx into the esophagus. The epiglottis folds down to a more horizontal position to direct the food into the esophagus, and away from the trachea

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all air- breathing animals with lungs. The trachea extends from t ...

.

Once in the esophagus, the bolus travels down to the stomach via rhythmic contraction and relaxation of muscles known as peristalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, whi ...

. The lower esophageal sphincter is a muscular sphincter surrounding the lower part of the esophagus. The gastroesophageal junction between the esophagus and the stomach is controlled by the lower esophageal sphincter, which remains constricted at all times other than during swallowing and vomiting to prevent the contents of the stomach from entering the esophagus. As the esophagus does not have the same protection from acid as the stomach, any failure of this sphincter can lead to heartburn.

Diaphragm

Thediaphragm

Diaphragm may refer to:

Anatomy

* Thoracic diaphragm, a thin sheet of muscle between the thorax and the abdomen

* Pelvic diaphragm or pelvic floor, a pelvic structure

* Urogenital diaphragm or triangular ligament, a pelvic structure

Other

* Diap ...

is an important part of the body's digestive system. The muscular diaphragm separates the thoracic cavity

The thoracic cavity (or chest cavity) is the chamber of the body of vertebrates that is protected by the thoracic wall (rib cage and associated skin, muscle, and fascia). The central compartment of the thoracic cavity is the mediastinum. There ...

from the abdominal cavity

The abdominal cavity is a large body cavity in humans and many other animals that contains many organs. It is a part of the abdominopelvic cavity. It is located below the thoracic cavity, and above the pelvic cavity. Its dome-shaped roof is th ...

where most of the digestive organs are located. The suspensory muscle attaches the ascending duodenum to the diaphragm. This muscle is thought to be of help in the digestive system in that its attachment offers a wider angle to the duodenojejunal flexure for the easier passage of digesting material. The diaphragm also attaches to, and anchors the liver at its bare area. The esophagus enters the abdomen through a hole in the diaphragm at the level of T10.

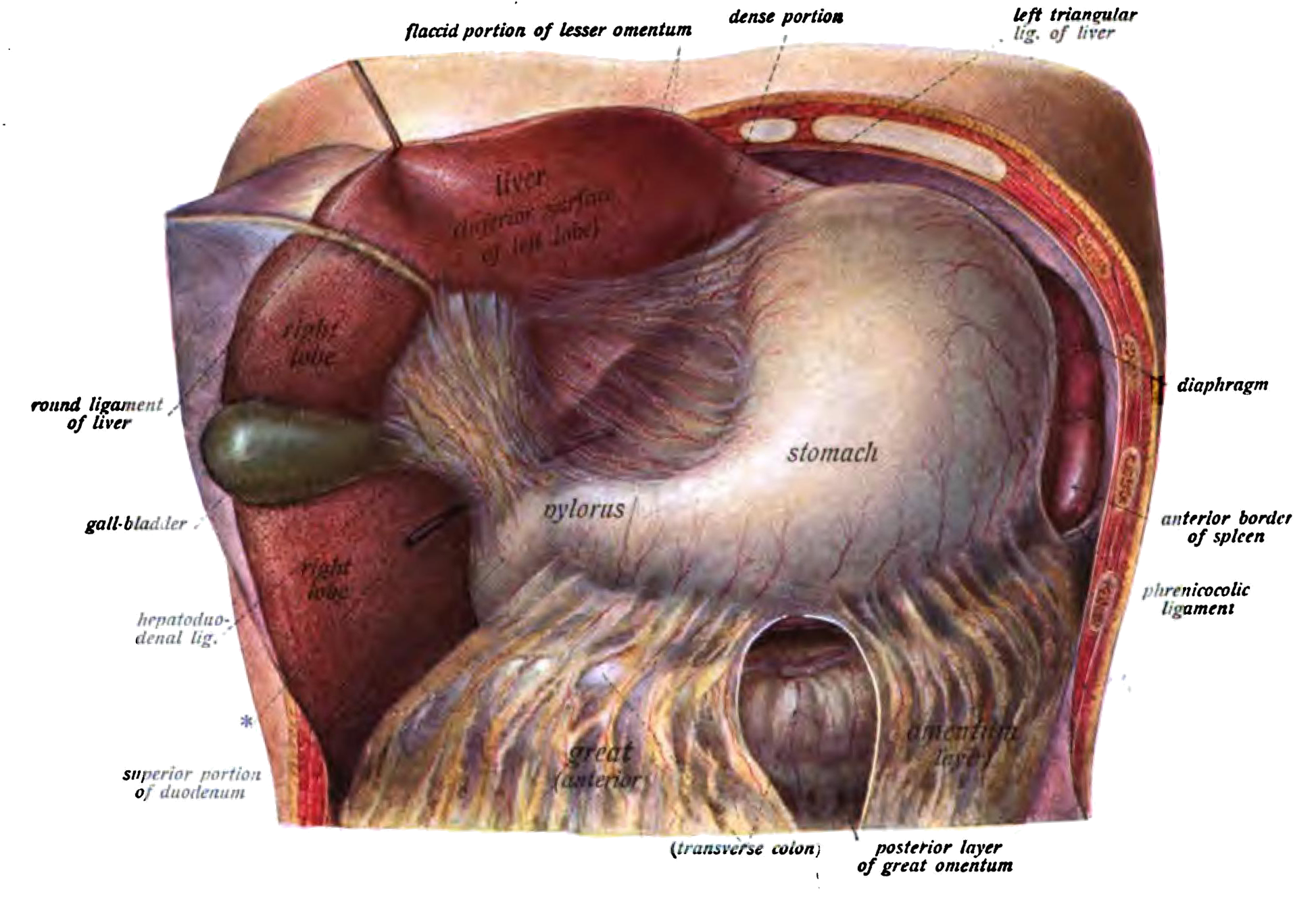

Stomach

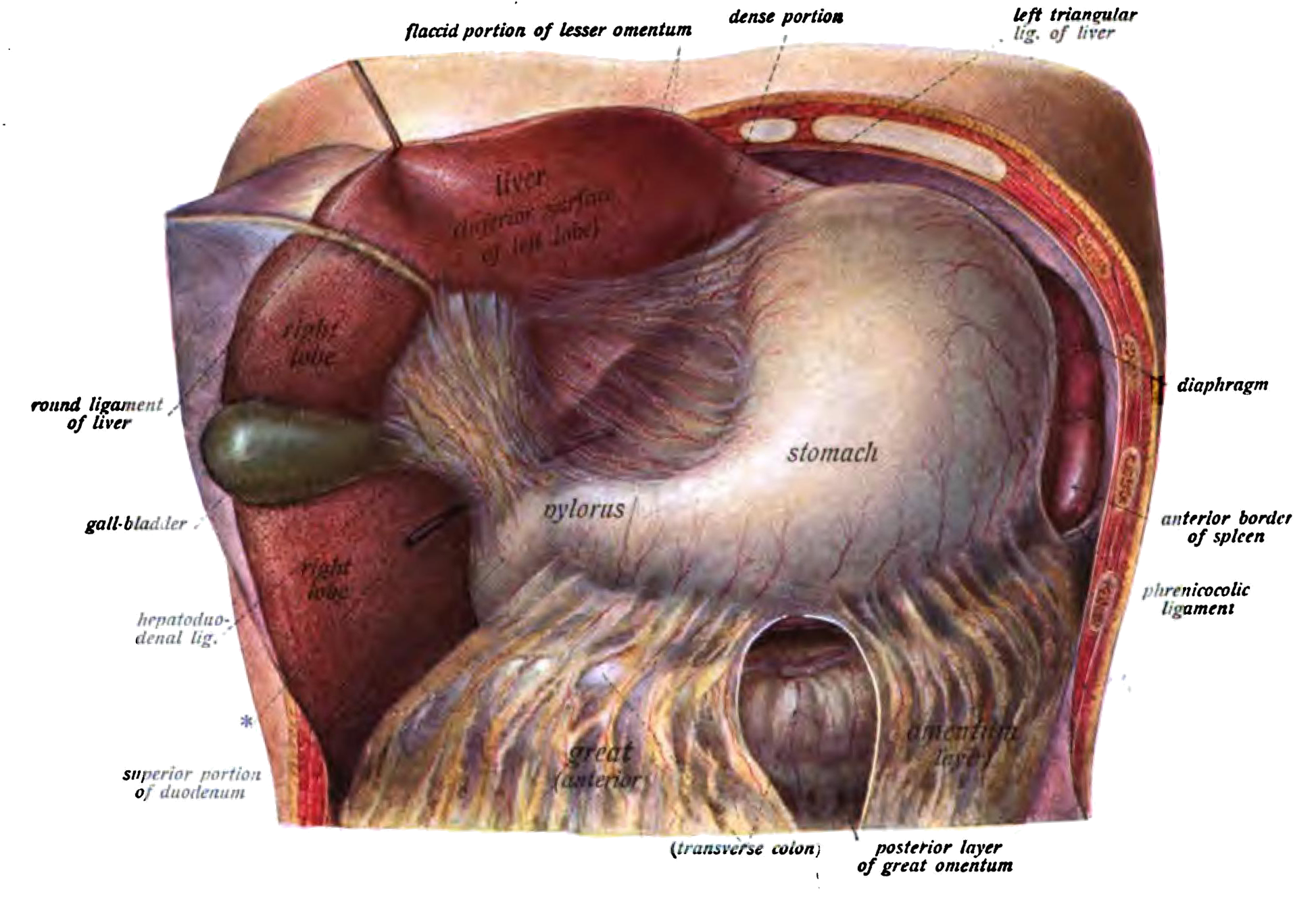

Thestomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach i ...

is a major organ of the gastrointestinal tract and digestive system. It is a consistently J-shaped organ joined to the esophagus at its upper end and to the duodenum at its lower end.

Gastric acid

Gastric acid, gastric juice, or stomach acid is a digestive fluid formed within the stomach lining. With a pH between 1 and 3, gastric acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins by activating digestive enzymes, which together break down the ...

(informally ''gastric juice''), produced in the stomach plays a vital role in the digestive process, and mainly contains hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride. It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungent smell. It is classified as a strong acid. It is a component of the gastric acid in the dige ...

and sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as salt (although sea salt also contains other chemical salts), is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. With molar masses of 22.99 and 35. ...

. A peptide hormone

Peptide hormones or protein hormones are hormones whose molecules are peptide, or proteins, respectively. The latter have longer amino acid chain lengths than the former. These hormones have an effect on the endocrine system of animals, including h ...

, gastrin

Gastrin is a peptide hormone that stimulates secretion of gastric acid (HCl) by the parietal cells of the stomach and aids in gastric motility. It is released by G cells in the pyloric antrum of the stomach, duodenum, and the pancreas.

Gast ...

, produced by G cell

In anatomy, the G cell or gastrin cell, is a type of cell in the stomach and duodenum that secretes gastrin. It works in conjunction with gastric chief cells and parietal cells. G cells are found deep within the pyloric glands of the stomach antru ...

s in the gastric glands

The gastric glands are glands in the lining of the stomach that play an essential role in the process of digestion. All of the glands have mucus-secreting foveolar cells. Mucus lines the entire stomach, and protects the stomach lining from the ...

, stimulates the production of gastric juice which activates the digestive enzyme

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

s. Pepsinogen

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, ...

is a precursor enzyme (zymogen

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the activ ...

) produced by the gastric chief cells, and gastric acid activates this to the enzyme pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides. It is produced in the gastric chief cells of the stomach lining and is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, w ...

which begins the digestion of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s. As these two chemicals would damage the stomach wall, mucus is secreted by innumerable gastric glands in the stomach, to provide a slimy protective layer against the damaging effects of the chemicals on the inner layers of the stomach.

At the same time that protein is being digested, mechanical churning occurs through the action of peristalsis

Peristalsis ( , ) is a radially symmetrical contraction and relaxation of muscles that propagate in a wave down a tube, in an anterograde direction. Peristalsis is progression of coordinated contraction of involuntary circular muscles, whi ...

, waves of muscular contractions that move along the stomach wall. This allows the mass of food to further mix with the digestive enzymes

Digestive enzymes are a group of enzymes that break down polymeric macromolecules into their smaller building blocks, in order to facilitate their absorption into the cells of the body. Digestive enzymes are found in the digestive tracts of anima ...

. Gastric lipase

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the gastrointestinal tract of humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The stomach has a dilated structure and functions as a vital organ in the digestive system. The stomach ...

secreted by the chief cells in the fundic glands in the gastric mucosa

The gastric mucosa is the mucous membrane layer of the stomach, which contains the glands and the gastric pits. In humans, it is about 1 mm thick, and its surface is smooth, soft, and velvety. It consists of simple columnar epithelium, lamin ...

of the stomach, is an acidic lipase, in contrast with the alkaline pancreatic lipase. This breaks down fats to some degree though is not as efficient as the pancreatic lipase.

The pylorus, the lowest section of the stomach which attaches to the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine m ...

via the pyloric canal

The pylorus ( or ), or pyloric part, connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pylori ...

, contains countless glands which secrete digestive enzymes including gastrin. After an hour or two, a thick semi-liquid called chyme

Chyme or chymus (; from Greek χυμός ''khymos'', "juice") is the semi-fluid mass of partly digested food that is expelled by a person's stomach, through the pyloric valve, into the duodenumpyloric sphincter

The pylorus ( or ), or pyloric part, connects the stomach to the duodenum. The pylorus is considered as having two parts, the ''pyloric antrum'' (opening to the body of the stomach) and the ''pyloric canal'' (opening to the duodenum). The ''pylori ...

, or valve opens, chyme enters the duodenum where it mixes further with digestive enzymes from the pancreas, and then passes through the small intestine, where digestion continues.

The parietal cells in the fundus of the stomach, produce a glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known as glyco ...

called intrinsic factor which is essential for the absorption of vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism. It is one of eight B vitamins. It is required by animals, which use it as a cofactor in DNA synthesis, in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. ...

. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin), is carried to, and through the stomach, bound to a glycoprotein secreted by the salivary glands - transcobalamin I also called haptocorrin, which protects the acid-sensitive vitamin from the acidic stomach contents. Once in the more neutral duodenum, pancreatic enzymes break down the protective glycoprotein. The freed vitamin B12 then binds to intrinsic factor which is then absorbed by the enterocyte

Enterocytes, or intestinal absorptive cells, are simple columnar epithelial cells which line the inner surface of the small and large intestines. A glycocalyx surface coat contains digestive enzymes. Microvilli on the apical surface increase i ...

s in the ileum.

The stomach is a distensible organ and can normally expand to hold about one litre of food. This expansion is enabled by a series of gastric folds in the inner walls of the stomach. The stomach of a newborn baby will only be able to expand to retain about 30 ml.

Spleen

Thespleen

The spleen is an organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter. The word spleen comes .

is the largest lymphoid organ in the body but has other functions. It breaks down both red and white blood cells that are ''spent''. This is why it is sometimes known as the 'graveyard of red blood cells'. A product of this ''digestion'' is the pigment bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) ( Latin for "red bile") is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normal catabolic pathway that breaks down heme in vertebrates. This catabolism is a necessary process in the body's clearance of waste products that arise from t ...

, which is sent to the liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

and secreted in the bile

Bile (from Latin ''bilis''), or gall, is a dark-green-to-yellowish-brown fluid produced by the liver of most vertebrates that aids the digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In humans, bile is produced continuously by the liver (liver bi ...

. Another product is iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, which is used in the formation of new blood cells in the bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

. Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

treats the spleen solely as belonging to the lymphatic system

The lymphatic system, or lymphoid system, is an organ system in vertebrates that is part of the immune system, and complementary to the circulatory system. It consists of a large network of lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, lymphatic or lymphoid ...

, though it is acknowledged that the full range of its important functions is not yet understood.

Liver

The

The liver

The liver is a major organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for digestion and growth. In humans, it i ...

is the second largest organ (after the skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

) and is an accessory digestive gland which plays a role in the body's metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

. The liver has many functions some of which are important to digestion. The liver can detoxify various metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, ...

s; synthesise protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, res ...

s and produce biochemical

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology an ...

s needed for digestion. It regulates the storage of glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. The polysaccharide structure represents the main storage form of glucose in the body.

Glycogen functions as one of ...

which it can form from glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, u ...

(glycogenesis

Glycogenesis is the process of glycogen synthesis, in which glucose molecules are added to chains of glycogen for storage. This process is activated during rest periods following the Cori cycle, in the liver, and also activated by insulin in ...

). The liver can also synthesise glucose from certain amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s. Its digestive functions are largely involved with the breaking down of carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may o ...

s. It also maintains protein metabolism in its synthesis and degradation. In lipid

Lipids are a broad group of naturally-occurring molecules which includes fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids in ...

metabolism it synthesises cholesterol

Cholesterol is any of a class of certain organic molecules called lipids. It is a sterol (or modified steroid), a type of lipid. Cholesterol is biosynthesized by all animal cells and is an essential structural component of animal cell memb ...

. Fats are also produced in the process of lipogenesis

In biochemistry, lipogenesis is the conversion of fatty acids and glycerol into fats, or a metabolic process through which acetyl-CoA is converted to triglyceride for storage in fat. Lipogenesis encompasses both fatty acid and triglyceride s ...

. The liver synthesises the bulk of lipoproteins. The liver is located in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen and below the diaphragm to which it is attached at one part, the bare area of the liver

The bare area of the liver (nonperitoneal area) is a large triangular area on the diaphragmatic surface of the liver. It is the only part of the liver with no peritoneal covering, although it is still covered by Glisson’s capsule. It is attach ...

. This is to the right of the stomach and it overlies the gall bladder

In vertebrates, the gallbladder, also known as the cholecyst, is a small hollow organ where bile is stored and concentrated before it is released into the small intestine. In humans, the pear-shaped gallbladder lies beneath the liver, although ...

. The liver synthesises bile acid

Bile acids are steroid acids found predominantly in the bile of mammals and other vertebrates. Diverse bile acids are synthesized in the liver. Bile acids are conjugated with taurine or glycine residues to give anions called bile salts.

Primar ...

s and lecithin

Lecithin (, from the Greek ''lekithos'' "yolk") is a generic term to designate any group of yellow-brownish fatty substances occurring in animal and plant tissues which are amphiphilic – they attract both water and fatty substances (and so a ...

to promote the digestion of fat.

Bile

Bile

Bile (from Latin ''bilis''), or gall, is a dark-green-to-yellowish-brown fluid produced by the liver of most vertebrates that aids the digestion of lipids in the small intestine. In humans, bile is produced continuously by the liver (liver bi ...

produced by the liver is made up of water (97%), bile salts, mucus and pigments

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compoun ...

, 1% fats and inorganic salts. Bilirubin

Bilirubin (BR) ( Latin for "red bile") is a red-orange compound that occurs in the normal catabolic pathway that breaks down heme in vertebrates. This catabolism is a necessary process in the body's clearance of waste products that arise from t ...

is its major pigment. Bile acts partly as a surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension between two liquids, between a gas and a liquid, or interfacial tension between a liquid and a solid. Surfactants may act as detergents, wetting agents, emulsion#Emulsifiers , ...

which lowers the surface tension between either two liquids or a solid and a liquid and helps to emulsify

An emulsion is a mixture of two or more liquids that are normally immiscible (unmixable or unblendable) owing to liquid-liquid phase separation. Emulsions are part of a more general class of two-phase systems of matter called colloids. Althoug ...

the fats in the chyme

Chyme or chymus (; from Greek χυμός ''khymos'', "juice") is the semi-fluid mass of partly digested food that is expelled by a person's stomach, through the pyloric valve, into the duodenummicelle

A micelle () or micella () (plural micelles or micellae, respectively) is an aggregate (or supramolecular assembly) of surfactant amphipathic lipid molecules dispersed in a liquid, forming a colloidal suspension (also known as associated coll ...

s. The breaking down into micelles creates a much larger surface area for the pancreatic enzyme, lipase