Destruction Of Country Houses In 20th-century Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The destruction of country houses in 20th-century Britain was the result of a change in social conditions: many

The destruction of country houses in 20th-century Britain was the result of a change in social conditions: many

Two years before the beginning of

Two years before the beginning of  Thus, it was not just the smaller country houses of the

Thus, it was not just the smaller country houses of the

The vast majority of the houses demolished were of less architectural importance than the great

The vast majority of the houses demolished were of less architectural importance than the great

Before the 19th century, the British upper classes enjoyed a life relatively free from taxation. Staff were plentiful and cheap, and estates not only provided a generous income from tenanted land but also political power. During the 19th century this began to change, by the mid-20th century their political power had weakened and they faced heavy tax burdens. The staff had either been killed in two world wars or forsaken a life of servitude for better wages elsewhere. Thus the owners of large country houses dependent on staff and a large income began by necessity to dispose of their costly non-self sustaining material assets. Large houses had become redundant

Before the 19th century, the British upper classes enjoyed a life relatively free from taxation. Staff were plentiful and cheap, and estates not only provided a generous income from tenanted land but also political power. During the 19th century this began to change, by the mid-20th century their political power had weakened and they faced heavy tax burdens. The staff had either been killed in two world wars or forsaken a life of servitude for better wages elsewhere. Thus the owners of large country houses dependent on staff and a large income began by necessity to dispose of their costly non-self sustaining material assets. Large houses had become redundant  Another consideration was education. Before the late 1950s and the advent of the

Another consideration was education. Before the late 1950s and the advent of the

As land prices and incomes continued to fall, the great London palaces were the first casualties; the peer no longer needed to use his London house to maintain a high prestige presence in the capital. Its site was often more valuable empty than with the anachronistic palace ''in situ''; selling them for redevelopment was the obvious first choice to raise some fast cash. The second choice was to sell part of the landed estate, especially if had been purchased in order to expand political territory. In fact, the buying of land in earlier times, before the reforms of 1885, to expand political territory had had a detrimental effect on country houses too. Often when a second estate was purchased to expand another, the purchased estate also had a country house. If the land (and its subsequent local influence) was the only requirement, its house would then be let or neglected, often both. This was certainly the case at Tong Castle (see below) and many other houses. A large unwanted country house unsupported by land quickly became a liability.

As land prices and incomes continued to fall, the great London palaces were the first casualties; the peer no longer needed to use his London house to maintain a high prestige presence in the capital. Its site was often more valuable empty than with the anachronistic palace ''in situ''; selling them for redevelopment was the obvious first choice to raise some fast cash. The second choice was to sell part of the landed estate, especially if had been purchased in order to expand political territory. In fact, the buying of land in earlier times, before the reforms of 1885, to expand political territory had had a detrimental effect on country houses too. Often when a second estate was purchased to expand another, the purchased estate also had a country house. If the land (and its subsequent local influence) was the only requirement, its house would then be let or neglected, often both. This was certainly the case at Tong Castle (see below) and many other houses. A large unwanted country house unsupported by land quickly became a liability.

The

The

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 was chiefly concerned with development and new planning regulations. However, amongst the small print was Clause 17, which permitted a town council to prevent the demolition of any property within its jurisdiction. This unpopular clause clearly intruded on the "Englishman's home is his castle" philosophy, and provoked similar aristocratic fury to that seen in 1911. The

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 was chiefly concerned with development and new planning regulations. However, amongst the small print was Clause 17, which permitted a town council to prevent the demolition of any property within its jurisdiction. This unpopular clause clearly intruded on the "Englishman's home is his castle" philosophy, and provoked similar aristocratic fury to that seen in 1911. The

The apathy towards the nation's heritage continued after the passing of the

The apathy towards the nation's heritage continued after the passing of the

By 1984 public and Government opinion had so changed that a campaign to save the semi-derelict

By 1984 public and Government opinion had so changed that a campaign to save the semi-derelict

List of ca. 2000 lost English country housesTown and Country Planning Act 1932

Published by Legislation.gov.uk. retrieved 3 December 2010.

Town and Country Planning Act 1968

Published by Legislation.gov.uk. retrieved 3 December 2010.

St Louis Art Museum

retrieved 22 March 2007

retrieved 9 December 2010.

retrieved 23 March 2007

retrieved 23 March 2007

BBC.CO.UK

retrieved 23 March 2007

British History Online

retrieved 25 March 2007

retrieved 25 March 2007

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20120903022529/http://www.scotlandsplaces.gov.uk/search_item/index.php?service=RCAHMS&id=213798 Scotland's Places; Bathgate, Balbardie Houseretrieved 9 December 2010. Demolished buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Houses in the United Kingdom

country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peop ...

s of varying architectural merit were demolished by their owners. Collectively termed by several authors "the lost houses", the destruction of these now often forgotten houses has been described as a cultural tragedy.

The British nobility

The British nobility is made up of the peerage and the (landed) gentry. The nobility of its four constituent home nations has played a major role in shaping the history of the country, although now they retain only the rights to stand for electio ...

had been demolishing some of their country houses since the 15th century, when comfort replaced fortification as an essential need. For many, demolishing and rebuilding their country homes became a lifelong hobby, in particular during the 18th century when it became fashionable to take the Grand Tour

The Grand Tour was the principally 17th- to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italy as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class young European men of sufficient means and rank (typically accompanied by a tut ...

and return home with art treasures, supposedly brought from classical civilization

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

s. During the 19th century, many houses were enlarged to accommodate the increasing numbers of servants needed to create the famed country house lifestyle. Less than a century later, this often meant they were of an unmanageable size.

In the early 20th century, the demolition accelerated while rebuilding largely ceased. The demolitions were not confined to England, but spread throughout Britain. By the end of the century, even some of the "new" country houses by the architect Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memor ...

had been demolished. There were a number of reasons: social, political and, most importantly, financial. In rural areas, the destruction of the country houses and their estates was tantamount to a social revolution. Well into the 20th century, it was common for the local squire to provide large-scale employment, housing, and patronage to the village school, parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

, and a cottage hospital A cottage hospital is a semi-obsolete type of small hospital, most commonly found in the United Kingdom.

The original concept was a small rural building having several beds.The Cottage Hospitals 1859–1990, Dr. Meyrick Emrys-Roberts, Tern Publicati ...

. The "big house" was the bedrock of rural society.

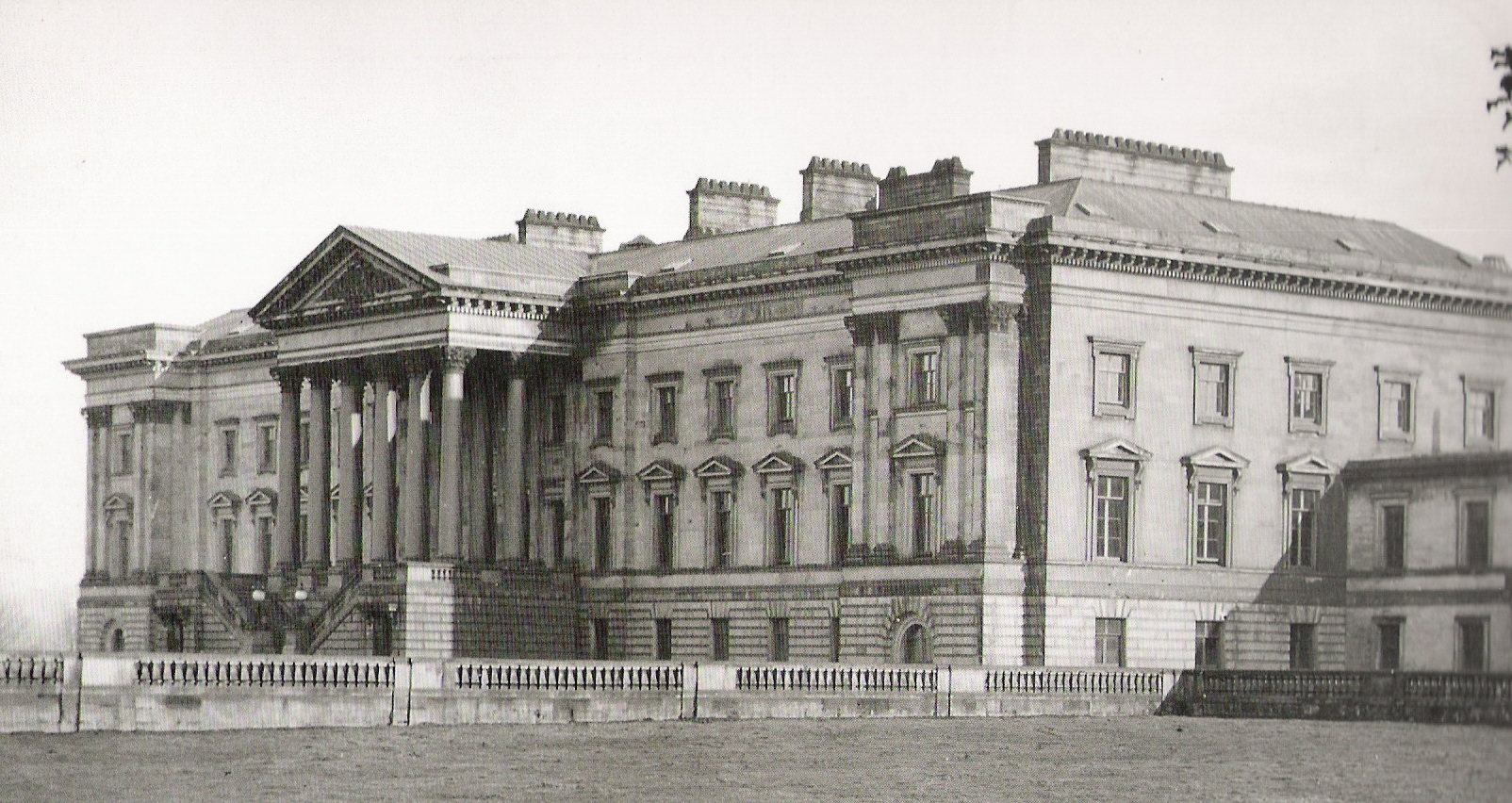

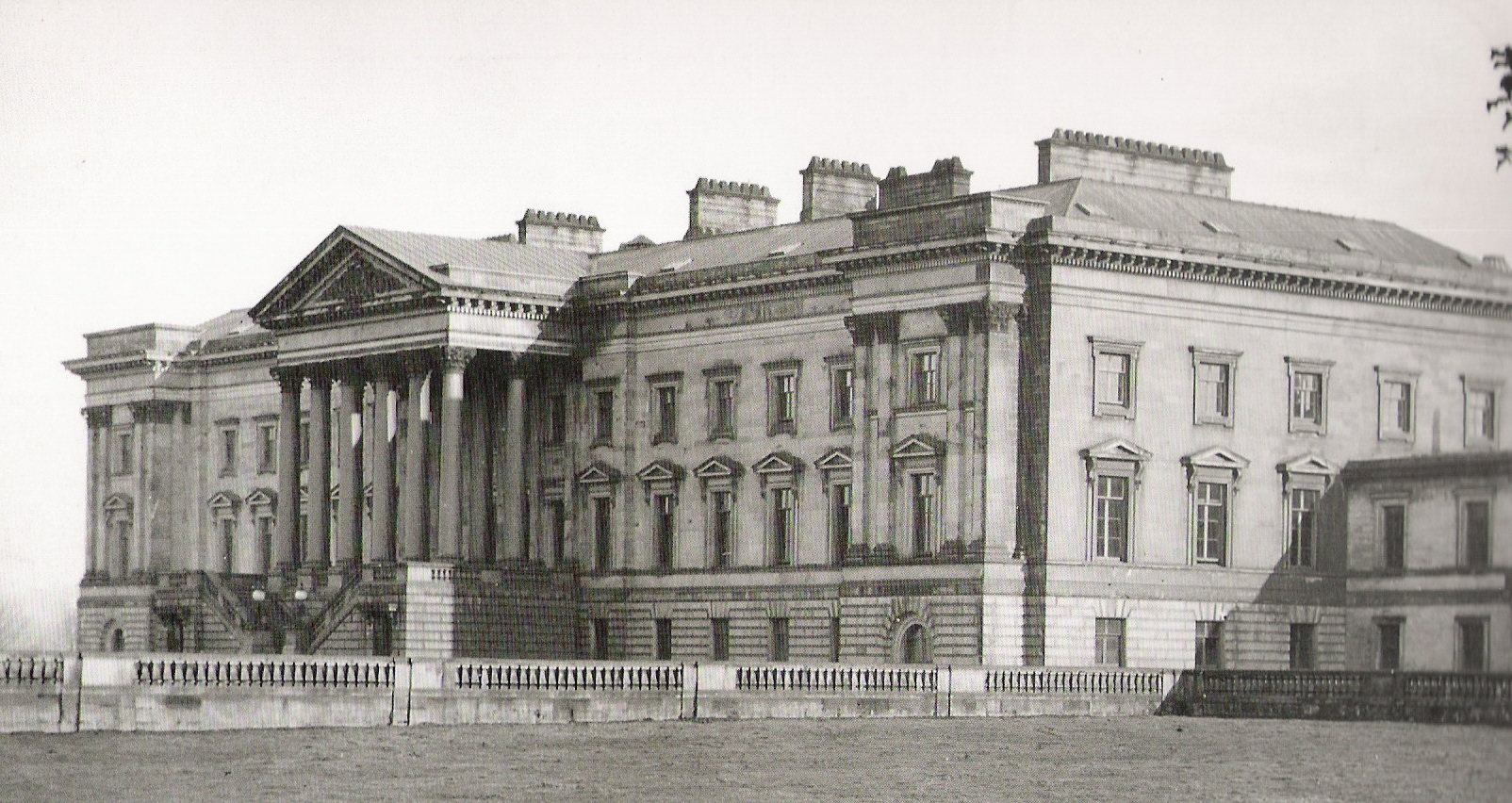

Since 1900, 1,200 country houses have been demolished in England.Worsley, p. 7. In Scotland, the figure is proportionally higher. There, 378 architecturally important country houses have been demolished, 200 of these since 1945. Included in the destruction were works by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his ...

, including Balbardie House and the monumental Hamilton Palace. One firm, Charles Brand of Dundee, demolished at least 56 country houses in Scotland in the 20 years between 1945 and 1965. In England, it has been estimated that one in six of all country houses were demolished during the 20th century.

Historical background

Two years before the beginning of

Two years before the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, on 4 May 1912, the British magazine '' Country Life'' carried a seemingly unremarkable advertisement: the roofing balustrade and urns from the roof of Trentham Hall

The Trentham Estate, in the village of Trentham, is a visitor attraction located on the southern fringe of the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

History

The estate was first recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086. At th ...

could be purchased for £200. One of Britain's great ducal country houses, Trentham Hall was demolished with little public comment or interest. It was its owner's property, to do with as he wished. There was no reason for public interest or concern; the same magazine had frequently published in-depth articles on new country houses being built, designed by fashionable architects such as Lutyens. As far as general opinion was concerned, England's great houses came and they went; as long as their numbers remained, continuing to provide local employment, the public were not largely concerned. The ''Country Life'' advertisement, however, was to prove a hint of things to come.

Before World War I only a few houses were demolished, but the pace increased: by 1955, one house was being demolished every five days. As early as 1944, the trustee

Trustee (or the holding of a trusteeship) is a legal term which, in its broadest sense, is a synonym for anyone in a position of trust and so can refer to any individual who holds property, authority, or a position of trust or responsibility to ...

s of Castle Howard

Castle Howard is a stately home in North Yorkshire, England, within the civil parish of Henderskelfe, located north of York. It is a private residence and has been the home of the Carlisle branch of the Howard family for more than 300 years ...

, convinced there was no future for Britain's great houses, had begun selling the house's contents. Increasing taxation and a shortage of staff meant that the old way of life had ended. The wealth and status of the owner provided no protection to the building: even the wealthier owners became keen to free themselves of not only the expense of a large house, but also the trappings of wealth and privilege which the house represented.Mulvagh, p. 321.

Thus, it was not just the smaller country houses of the

Thus, it was not just the smaller country houses of the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

which were wiped from their – often purposely built – landscapes, but also the huge ducal palaces. Alfred Waterhouse

Alfred Waterhouse (19 July 1830 – 22 August 1905) was an English architect, particularly associated with the Victorian Gothic Revival architecture, although he designed using other architectural styles as well. He is perhaps best known ...

's Gothic Eaton Hall, owned by Britain's wealthiest peer, was razed to the ground in 1963, and replaced by a smaller modern building. Sixteen years earlier the Duke of Bedford

Duke of Bedford (named after Bedford, England) is a title that has been created six times (for five distinct people) in the Peerage of England. The first and second creations came in 1414 and 1433 respectively, in favour of Henry IV's third so ...

had reduced Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

to half its original size, destroying façades and interiors by both Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a simple background: his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court and he began as a joiner by ...

and Henry Holland. The Duke of Devonshire

Duke of Devonshire is a title in the Peerage of England held by members of the Cavendish family. This (now the senior) branch of the Cavendish family has been one of the wealthiest British aristocratic families since the 16th century and ha ...

saved Hardwick Hall

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire is an architecturally significant country house from the Elizabethan era, a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house. Built between 1590 and 1597 for Bess of Hardwick, it was designed by the architect ...

by surrendering it to H.M. Treasury in lieu of death duties, which were charged at up to 80% of the total value of an estate, but this solution was rarely acceptable to the government. As late as 1975, the British Labour government refused to save Mentmore

Mentmore is a village and civil parish in the Aylesbury Vale district of Buckinghamshire, England. It is about three miles east of Wingrave, three miles south east of Wing.

The village toponym is derived from the Old English for "Menta's moor ...

, thus causing the dispersal, and emigration, of one of the country's finest art collections..

In the 1960s, historians and public bodies had begun to realise the loss to the nation of this destruction. However, the process of change was long, and it was not until 1984 with the preservation of Calke Abbey

Calke Abbey is a Grade I listed country house near Ticknall, Derbyshire, England, in the care of the charitable National Trust.

The site was an Augustinian priory from the 12th century until its dissolution by Henry VIII. The present building ...

that it became obvious that opinion had changed. A large public appeal assured the preservation of Tyntesfield in 2002, and in 2007, Dumfries House and its collection were saved, after protracted appeals and debates. Today, demolition has ceased to be a realistic, or legal, option for listed buildings, and an historic house (particularly one with its contents intact) has become recognized as worthy of retention and preservation. However, many country houses are still at risk; and their security, even as an entirety with their contents, is not guaranteed by any legislation.

Impoverished owners and a plethora of country houses

WhenEvelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires '' Decl ...

's novel ''Brideshead Revisited

''Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder'' is a novel by English writer Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1945. It follows, from the 1920s to the early 1940s, the life and romances of the protagonist Charles ...

'', portraying life in the English country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

, was published in 1945, its first few chapters offered a glimpse of an exclusive and enviable world, a world of beautiful country houses with magnificent contents, privileged occupants, a profusion of servants and great wealth. Yet, in its final chapters, Brideshead's author accurately documented a changing and fading world, a world in which the country house as a symbol of power, privilege and a natural order, was not to exist.

As early as June 1940, while Britain was embroiled in the early days of World War II, ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'', confident of future victory, advised its readers that "a new order cannot be based on the preservation of privilege, whether the privilege be that of a county, a class, or an individual." Thus it was after the end of the war, as the government handed back the requisitioned, war-torn and frequently dilapidated mansions to their often demoralised and impoverished owners; it was during a period of not just mounting taxation, to pay for a costly war, but also a time when it seemed all too clear that the old order had passed. In this political climate, many felt it the only option to abandon their ancestral piles. Thus, following the cessation of hostilities, the trickle of demolitions which had begun in the earlier part of the century became a torrent of destruction.

Destroying buildings of national or potential national importance was not an act peculiar to the 20th century in Britain. The demolition in 1874 of Northumberland House, London, a prime example of English Renaissance

The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England from the early 16th century to the early 17th century. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th cent ...

architecture, passed without significant comment. Town houses such as Northumberland House were highly visible displays of wealth and political power, so consequently more likely to be the victims of changing fashions.

The difference in the 20th century was that the acts of demolition were often acts of desperation and last resort; a demolished house could not be valued for probate

Probate is the judicial process whereby a will is "proved" in a court of law and accepted as a valid public document that is the true last testament of the deceased, or whereby the estate is settled according to the laws of intestacy in the st ...

duty. A vacant site was attractive to property developers, who would pay a premium for an empty site that could be rebuilt upon and filled with numerous small houses and bungalows, which would return a quick profit. This was especially true in the years immediately following World War II, when Britain was desperate to replace the thousands of homes destroyed. Thus, in many cases, the demolition of the ancestral seat, strongly entwined with the family's history and identity, followed the earlier loss of the family's London house.Worsley, p. 12.

A significant factor, which explained the seeming ease with which a British aristocrat could dispose of his ancestral seat, was the aristocratic habit of only marrying within the aristocracy and whenever possible to a sole heiress. This meant that by the 20th century, many owners of country houses often owned several country mansions. Thus it became a favoured option to select the most conveniently sited (whether for privacy or sporting reasons), easily managed, or of greatest sentimental value; fill it with the choicest art works from the other properties; and then demolish the less favoured. Thus, one solution not only solved any financial problems, but also removed an unwanted burden.

The vast majority of the houses demolished were of less architectural importance than the great

The vast majority of the houses demolished were of less architectural importance than the great Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including ...

, Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

and Neoclassical mansions by the notable architects. These smaller, but often aesthetically pleasing houses belonged to the gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

rather the aristocracy; in these cases the owners, little more than gentlemen farmers, often razed the ancestral home to save costs and thankfully moved into a smaller but more comfortable farmhouse or purpose-built new house on the estate.

Occasionally an aristocrat of the first rank did find himself in dire financial troubles. The severely impoverished Duke of Marlborough saved Blenheim Palace

Blenheim Palace (pronounced ) is a country house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough and the only non- royal, non-episcopal country house in England to hold the title of palace. The palace, ...

by marrying an heiress, tempted from the USA by the lure of an old title in return for vast riches.Stuart, p. 135. Not all were so fortunate or seemingly eligible. When 2nd Duke of Buckingham found himself bankrupt in 1848, he sold the contents of Stowe House

Stowe House is a grade I listed country house in Stowe, Buckinghamshire, England. It is the home of Stowe School, an independent school and is owned by the Stowe House Preservation Trust who have to date (March 2013) spent more than £25m on t ...

, one of Britain's grandest houses. It proved to be a temporary solution; his heirs, the 3rd and final Duke of Buckingham

Duke of Buckingham held with Duke of Chandos, referring to Buckingham, is a title that has been created several times in the peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. There have also been earls and marquesses of Buckingham.

...

and his heirs, the Earls Temple

The Baronetcy of Temple, of Stowe, in the Baronetage of England, was created on 24 September 1611 for Thomas Temple, eldest son of John Temple of Stowe, Buckinghamshire. His great-grandson Sir Richard, 4th Baronet, was created Baron Cobham on 19 ...

, inherited huge financial problems until finally in 1922 anything left that was moveable, both internal and external, was auctioned off and the house sold, narrowly escaping demolition. It was saved by being transformed into a school. Less fortunate was Clumber Park

Clumber Park is a country park in The Dukeries near Worksop in Nottinghamshire, England. The estate, which was the seat of the Pelham-Clintons, Dukes of Newcastle, was purchased by the National Trust in 1946. It is listed Grade I on the Register ...

, the principal home of the Dukes of Newcastle. Selling the Hope Diamond

The Hope Diamond is a diamond originally extracted in the 17th century from the Kollur Mine in Guntur, India. It is blue in color due to trace amounts of boron. Its exceptional size has revealed new information about the formation of diamonds. ...

and other properties failed to solve the family problems, leaving no alternative but demolition of the huge, expensive-to-maintain house, which was razed to the ground in 1938, leaving the Duke without a ducal seat. Plans to rebuild a smaller house on the site were never executed. Other high-ranking members of the peerage were also forced to off-load minor estates and seats; the Duke of Northumberland retained Alnwick Castle

Alnwick Castle () is a castle and country house in Alnwick in the English county of Northumberland. It is the seat of the 12th Duke of Northumberland, built following the Norman conquest and renovated and remodelled a number of times. It is a G ...

, but sold Stanwick Park

Stanwick Park (also known as Stanwick Hall) was a Palladian country house at Stanwick St John in North Yorkshire, England. It was re-built by the 1st Duke of Northumberland, a great patron of the arts, , mostly to his own designs. The duke's pri ...

in North Yorkshire

North Yorkshire is the largest ceremonial county (lieutenancy area) in England, covering an area of . Around 40% of the county is covered by national parks, including most of the Yorkshire Dales and the North York Moors. It is one of four co ...

to be demolished, leaving him with four other country seats remaining.Worsley, p. 9. Likewise the Duke of Bedford kept Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

, considerably reduced in size, after World War II, while selling other family estates and houses. Whatever the personal choices and reasons for the sales and demolitions, the underlying and unifying factor was almost always financial. This began long before the 20th century with the gradual introduction and increase of taxes on income and further tax on inherited wealth, death duties

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an ...

.

Direct causes

white elephant

A white elephant is a possession that its owner cannot dispose of, and whose cost, particularly that of maintenance, is out of proportion to its usefulness. In modern usage, it is a metaphor used to describe an object, construction project, sch ...

s to be abandoned or demolished. It seemed that in particular regard to the country houses no one was prepared to save them.

There are several reasons which had brought about this situation – most significantly in the early 20th century there was no firmly upheld legislation to protect what is now considered to be the nation's heritage. Additionally, public opinion did not have the sentiment and interest in national heritage that is evident in Britain today. When the loss of Britain's architectural heritage reached its height at the rate of one house every five days in 1955, few were particularly interested or bothered. In the immediate aftermath of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, to the British public still suffering from the deprivations of food rationing and restriction on building work the destruction of these great redundant houses was of little interest. From 1914 onwards there had been a huge exodus away from a life in domestic service; having experienced the less restricted and better-paid life away from the great estates, few were anxious to return – this in itself was a further reason that life in the English country house was becoming near impossible to all but the very rich.

Another consideration was education. Before the late 1950s and the advent of the

Another consideration was education. Before the late 1950s and the advent of the stately home

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

business, very few working-class people had seen the upstairs of these great houses; those who had were there only to clean and serve, with an obligation to keep their eyes down, rather than uplift them and be educated. Thus ignorance of the nation's heritage was a large contributory factor to the indifference that met the destruction.

There were, however, reasons other than public indifference. Successive legislation involving national heritage, often formulated by the aristocracy themselves, had omitted any reference to private houses. The main reasons that so many British country houses were destroyed during the second half of the 20th century are politics and social conditions. During the Second World War many large houses were requisitioned, and subsequently for the duration of the war were used for the billeting of military personnel, government operations, hospitals, schools and a myriad of other uses far removed from the purpose for which they were designed. At the end of the war when handed back to the owners, many were in a poor or ruinous state of repair. During the next two decades, restrictions were applied to building works as Britain was rebuilt, priority being given to replacing what had been lost during the war rather than the oversized home of an elite family. In addition, death duties

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an ...

were raised to all-time highs by the new Labour Government that swept into power in 1945; this hit Britain's aristocracy hard. These factors, coupled with a decrease in people available or willing to work as servants, left the owners of country houses facing major problems of how to manage their estates. The most obvious solution was to off-load the cash-eating family mansion. Many were offered for sale as suitable for institutional use; those not readily purchased were speedily demolished. In the years immediately after the war, the law was powerless — even had it wished to — to stop the demolition of a private house no matter how architecturally important.

Loss of income from the estate

Before the 1870s, these estates often encompassed several thousand acres, generally consisting of several farms let to tenants; the great house was supplied with food from its own home farm (for meat and dairy) and akitchen garden

The traditional kitchen garden, vegetable garden, also known as a potager (from the French ) or in Scotland a kailyaird, is a space separate from the rest of the residential garden – the ornamental plants and lawn areas. It is used for grow ...

(for fruit and vegetables). While such estates were sufficiently profitable to maintain the mansion and provide a partial—if not complete—income, the agricultural depression from the 1870s onwards changed the viability of estates in general. Previously, such holdings yielded at least enough to fund loans on the large debts and mortgages usually undertaken to fund a lavish lifestyle, often spent in entertaining both on the country estate and "in town", in the family's large house of equal status in London.

By 1880, the so-called Long Depression

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic recession, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing st ...

had led some holders into financial shortfalls as they tried to balance maintenance of their estate with the income it provided. Some relied on funds from secondary sources such as banking and trade while others, like the severely impoverished Duke of Marlborough, sought American heiresses.

Loss of political power

The country houses have been described as "power houses", from which their owners controlled not only the vast surrounding estates, but also, through political influence, the people living in the locality. Political elections held in public before 1872 gavesuffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

to only a limited section of the community, many of whom were the landowner's friends, tradesmen with whom he dealt, senior employees or tenants. The local landowner often not only owned an elector's house, but was also his employer, and it was not prudent for the voter to be seen publicly voting against his local candidate.

The Third Reform Act of 1885 widened the number of males eligible to vote to 60% of the population. Males paying an annual rental of £10, or holding land valued at £10 or over, were now eligible to vote. The other factor was the reorganization of constituency boundaries, and a candidate who for years had been returned unopposed suddenly found part of his electorate was from an area outside of his influence. Thus the national power of the landed aristocrats and gentry was slowly diminished. The ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society. In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the capitalist social class who own the means of production and by ex ...

was slowly ceasing to rule. In 1888 the creation of local elected authorities in the form of county councils eroded their immediate local power too. The final blow, the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Pa ...

, proved to be the beginning of the end for the country house lifestyle which had been enjoyed in a similar way for generations of the upper classes.

As land prices and incomes continued to fall, the great London palaces were the first casualties; the peer no longer needed to use his London house to maintain a high prestige presence in the capital. Its site was often more valuable empty than with the anachronistic palace ''in situ''; selling them for redevelopment was the obvious first choice to raise some fast cash. The second choice was to sell part of the landed estate, especially if had been purchased in order to expand political territory. In fact, the buying of land in earlier times, before the reforms of 1885, to expand political territory had had a detrimental effect on country houses too. Often when a second estate was purchased to expand another, the purchased estate also had a country house. If the land (and its subsequent local influence) was the only requirement, its house would then be let or neglected, often both. This was certainly the case at Tong Castle (see below) and many other houses. A large unwanted country house unsupported by land quickly became a liability.

As land prices and incomes continued to fall, the great London palaces were the first casualties; the peer no longer needed to use his London house to maintain a high prestige presence in the capital. Its site was often more valuable empty than with the anachronistic palace ''in situ''; selling them for redevelopment was the obvious first choice to raise some fast cash. The second choice was to sell part of the landed estate, especially if had been purchased in order to expand political territory. In fact, the buying of land in earlier times, before the reforms of 1885, to expand political territory had had a detrimental effect on country houses too. Often when a second estate was purchased to expand another, the purchased estate also had a country house. If the land (and its subsequent local influence) was the only requirement, its house would then be let or neglected, often both. This was certainly the case at Tong Castle (see below) and many other houses. A large unwanted country house unsupported by land quickly became a liability.

Loss of wealth through taxation

Income tax

Income tax

An income tax is a tax imposed on individuals or entities (taxpayers) in respect of the income or profits earned by them (commonly called taxable income). Income tax generally is computed as the product of a tax rate times the taxable income. Ta ...

was first introduced in Great Britain in 1799 as a means of subsidising the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

. While not imposed in Ireland, the rate of 10% on the total income, with reductions only possible in incomes below £200, immediately hit the better off. The tax was repealed for a brief period in 1802 during a cessation in hostilities with the French, but its reintroduction in 1803 set the pattern for all future taxation in Britain. While the tax was again repealed following the victory at Waterloo, the advantages of such taxation were now obvious. In 1841, after the election victory of Sir Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Exchequer ...

, the exchequer was so depleted that the tax made a surprise return on incomes above £150, while still known as a "temporary tax". It was never again repealed. Throughout the 19th century, tax thresholds remained high, permitting the wealthy to live comfortably while paying minimal tax; until in 1907, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom ...

introduced 'differentiation', a tax designed to be more punitive to those with investments rather than an earned income, which directly hit the aristocracy and gentry. Two years later, Lloyd George in his People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

of 1909 announced plans for a supertax for the rich, but the bill introducing the tax was defeated in the House of Lords. This respite for owners of large country houses, many of them members of the House of Lords, was brief and ultimately self-defeating: the bill's defeat led to the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Pa ...

which removed the Lords' power of veto. In 1932, the threat through taxation to the nation's heritage was recognized, and appeals were made for repairs to National Trust and historic properties by their tenants to be tax-deductible; however the pleas fell on deaf ears.

Death duties

Death duties are the taxes most commonly associated with the decline of the British country house. They are not, in fact, a phenomenon peculiar to the 20th century, as they had first been introduced in 1796. "Legacy duty" was a tax payable on money bequeathed from a personal estate. Next of kin inheriting were exempt from payment, but anyone other than wives and children of the deceased had to pay on an increasing scale depending on the distance of the relationship from the deceased. These taxes gradually increased not only the percentage of the estate that had to be paid, but also to include closer heirs liable to payment. By 1815, the tax was payable by all except the spouse of the deceased.The National Archives; Series reference IR 26. In 1853, a new tax was introduced, "succession duty

An inheritance tax is a tax paid by a person who inherits money or property of a person who has died, whereas an estate tax is a levy on the estate (money and property) of a person who has died.

International tax law distinguishes between an e ...

". This not only resulted in tax being payable on all forms of inheritance, but also removed several loopholes to avoid paying inheritance taxes. In 1881 "probate duty" became payable on all personal property bequeathed at death. The wording personal property meant that for the first time not only the house and its estate were taxed but also the contents of the house including jewellery – these were often of greater value than the estate itself. By 1884 estate duty taxed property of any manner bequeathed at death, but even when the Liberal government in 1894 reformed and tidied the complicated system at 8% on properties valued at over one million pounds, they were not punitive to a social class able to live comfortably off inherited wealth far below that sum. Death duties, however, slowly increased and became a serious problem for the country estate throughout the first half of the 20th century, reaching a zenith when assisting in the funding of World War II. This proved to be the deciding factor for many families when in 1940 death duties were raised from 50% to 65%, and following the cessation of hostilities they were twice raised further between 1946 and 1949. Attempts by some families to avoid paying death duties were both helped and hindered by war. Some estate owners gave their properties to their heirs thereby escaping duties; when subsequently that heir was killed fighting, death duties were not payable because a soldier's or sailor's (and later airman's) estate was not subject to the tax. However, if the heir had died single and intestate, the former owner would become the owner again, and when that owner died, the death taxes would have to be paid.

Legislation to protect the national heritage

1882 and 1900 Ancient Monument and Amendment Acts

The

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (as it then was). It was introduced by John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, recognising the need for a governmental administrat ...

was the first serious attempt in Britain to catalogue and preserve ancient British monuments. While the Acts failed to protect any country houses, the Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1900

The Ancient Monuments Act 1900 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that aimed to improve the protection afforded to ancient monuments in Britain.

Details

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 had begun the process of establis ...

provided one important factor which saved many monuments of national importance by making provision for owners of ancient monuments (on list of the 1882 catalogue) to enter into agreement with civil authorities whereby the property was placed under public guardianship.

While these agreements did not divest the owner of the title to the property, they imposed on the civil authority an obligation to maintain and preserve for the nation. So while the Acts may have been in favour of the owner, they set a precedent for the later preservation of structures of national importance. The main problem with the Acts was that, out of all Britain's great buildings, they only found 26 monuments in England, 22 in Scotland, eighteen in Ireland and three in Wales worthy of preservation; all of which were prehistoric.

While neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

monuments were included, the Acts specifically excluded inhabited residences. The aristocratic ruling class of Britain inhabiting their homes and castles were certainly not going to be regulated by some lowly civil servants. This view was exemplified in 1911 when the immensely wealthy Duke of Sutherland

Duke of Sutherland is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom which was created by William IV in 1833 for George Leveson-Gower, 2nd Marquess of Stafford. A series of marriages to heiresses by members of the Leveson-Gower family made th ...

acting on a whim wished to dispose of Trentham Hall

The Trentham Estate, in the village of Trentham, is a visitor attraction located on the southern fringe of the city of Stoke-on-Trent in Staffordshire, United Kingdom.

History

The estate was first recorded in the Domesday Book in 1086. At th ...

, a vast Italianate

The Italianate style was a distinct 19th-century phase in the history of Classical architecture. Like Palladianism and Neoclassicism, the Italianate style drew its inspiration from the models and architectural vocabulary of 16th-century Italian ...

palace in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation Staffs.) is a landlocked county in the West Midlands region of England. It borders Cheshire to the northwest, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, Warwickshire to the southeast, the West Midlands C ...

. After failing to offload the house onto a local authority, he decided to demolish it. The small, but vocal, public resistance to this plan caused the Duke of Rutland

Duke of Rutland is a title in the Peerage of England, named after Rutland, a county in the East Midlands of England. Earldoms named after Rutland have been created three times; the ninth earl of the third creation was made duke in 1703, in whos ...

to write an irate letter to ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' ( ...

'' accusing the objectors of "impudence" and going on to say ''"....fancy my not being allowed to make a necessary alteration to Haddon without first obtaining the leave of some inspector''". There was an irony in the Duke of Rutland's words, as this same duke was responsible for resurrecting one of his own country houses, Haddon Hall

Haddon Hall is an English country house on the River Wye near Bakewell, Derbyshire, a former seat of the Dukes of Rutland. It is the home of Lord Edward Manners (brother of the incumbent Duke) and his family. In form a medieval manor house, ...

, from ruin. Thus, despite money being no problem for its owner, Trentham Hall was obliterated from its park, which the duke retained and then opened to the public. Thus it was that country houses were left unprotected by any compulsory legislation.

The Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913

The Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that aimed to improve the protection afforded to ancient monuments in Britain.

Details

The Ancient Monuments Protection Act 1882 had b ...

was the first Act which had the aim of deliberately preserving ancient monuments built since prehistoric times. The act clearly defined a monument as "Any structure or erection other than one in ecclesiastical use."Mynors, p. 9. Furthermore, the Act compelled the owner of any monument on the list to notify the newly formed Ancient Monuments Board of any proposed alterations, including demolition. The board then had the authority, if minded, to recommend that Parliament place a preservation order on a building, regardless of the owner's wishes, and thus protect it.

Like its predecessors, the 1913 Act deliberately omitted inclusion of inhabited buildings, whether they were castles or palaces. The catalyst for the 1913 Act had been the threat to Tattershall Castle, Lincolnshire. An American millionaire wished to purchase the uninhabited castle, and ship it to the USA in its entirety. To frustrate the proposal, the castle had been purchased and restored by Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

and thus the export of Lord Cromwell

Baron Cromwell is a title that has been created several times in the Peerage of England. The first creation, which was by writ, was for John de Cromwell in 1308. On his death, the barony became extinct. The second creation came in 1375 when Ral ...

's castle was prevented. The 1913 Act was an important step in highlighting the risk to the nation's many historic buildings. The Act also went further than its predecessors by decreeing that the public should have access to the monuments preserved at its expense.

While the catalogue of buildings worthy of preservation was to expand, it remained restrictive, and failed to prevent many of the early demolitions, including, in 1925, the export to the USA of the near ruinous Agecroft Hall

Agecroft Hall is a Tudor architecture, Tudor manor house and estate located at 4305 Sulgrave Road on the James River (Virginia), James River in the Windsor Farms neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia, United States. The manor house was built in the ...

. This fine half-timbered example of Tudor domestic architecture, was shipped, complete with its timbers, wattle and daub, across the Atlantic. In 1929 Virginia House was also bought, disassembled and shipped across the Atlantic.

In 1931, the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913 was amended to restrict development in an area surrounding an ancient monument. The scope of buildings included was also widened to include "any building, structure or other work, above or below the surface".Mynors, p. 10. However, the Act still excluded inhabited buildings. Had it included them, much that was destroyed before World War II could have been saved.

Town and Country Planning Act 1932

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 was chiefly concerned with development and new planning regulations. However, amongst the small print was Clause 17, which permitted a town council to prevent the demolition of any property within its jurisdiction. This unpopular clause clearly intruded on the "Englishman's home is his castle" philosophy, and provoked similar aristocratic fury to that seen in 1911. The

The Town and Country Planning Act 1932 was chiefly concerned with development and new planning regulations. However, amongst the small print was Clause 17, which permitted a town council to prevent the demolition of any property within its jurisdiction. This unpopular clause clearly intruded on the "Englishman's home is his castle" philosophy, and provoked similar aristocratic fury to that seen in 1911. The Marquess of Hartington

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman ...

thundered: "Clause 17 is an abominably bad clause, these buildings have been preserved to us not by Acts of Parliament, but by the loving care of generations of free Englishmen who...did not know what a District Council was".Mynors, p. 11. The marquess, so against enforced preservation, was in fact a member of the Royal Commission of Ancient and Historical Monuments, in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

, the very body which oversaw the implementation of the acts intended to enforce preservation. Thus, when the Act was finally passed after approval from the House of Lords, the final paragraph excluded from the act "any building included in a list of monuments published by the Commissioners of Works" and more tellingly did not "affect any powers of the Commissioners of Works." Ironically, eighteen years later, on the untimely death of the marquess, by then Duke of Devonshire, his son was forced to surrender to the state, in lieu of death duties, one of England's most historic country houses, Hardwick Hall

Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire is an architecturally significant country house from the Elizabethan era, a leading example of the Elizabethan prodigy house. Built between 1590 and 1597 for Bess of Hardwick, it was designed by the architect ...

, now owned by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

. The Devonshire's London house, Devonshire House had been demolished in 1920, and its site redeveloped.

Town and Country Planning Act 1944

The Town and Country Planning Act 1944, with the end of World War II in sight, was chiefly concerned with the redevelopment of bomb sites, but contained one crucial clause which concerned historic buildings: it charged local authorities to draw up a list of all buildings of architectural importance in their area, and, most significantly, for the first time the catalogue was to include inhabited private residences. This legislation created the foundations for what are today known aslisted building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

s. Under the scheme, an interesting or historic building was graded according to its value to the national heritage:

*Grade I (buildings of exceptional interest)

*Grade II* (buildings of more than special interest)

*Grade II (buildings of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them) English Heritage, "Listed Buildings"

The Act criminalised unauthorised alterations, or demolitions, to a listed building, so in theory at least, all historic buildings were now safe from unauthorised demolition. The truth was that the Act was rarely enforced, only a few buildings were listed, over half of them by just one council, Winchelsea

Winchelsea () is a small town in the non-metropolitan county of East Sussex, within the historic county of Sussex, England, located between the High Weald and the Romney Marsh, approximately south west of Rye and north east of Hastings. The ...

. Elsewhere, the fines levied on those failing to comply with the Act were far less than the profit from redeveloping a site. Little changed. In 1946, in what has been described as "an act of sheer class-war vindictiveness", Britain's Labour government insisted on the destruction, by open cast mining, of the park and formal gardens of Wentworth Woodhouse

Wentworth Woodhouse is a Grade I listed country house in the village of Wentworth, in the Metropolitan Borough of Rotherham in South Yorkshire, England. It is currently owned by the Wentworth Woodhouse Preservation Trust. The building has ...

, Britain's largest country house. The Minister of Fuel and Power, Manny Shinwell

Emanuel Shinwell, Baron Shinwell, (18 October 1884 – 8 May 1986) was a British politician who served as a government minister under Ramsay MacDonald and Clement Attlee. A member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament (MP) ...

, insisted, as 300-year-old oaks were uprooted, that "the park be mined right up to the mansion's door." Meanwhile, plans by the socialist government to wrest the house from its owner, the Earl Fitzwilliam, and convert the architecturally important house for "homeless industrial families" were only abandoned at the eleventh hour when Earl Fitzwilliam, through the auspices of his socialist sister, agreed to its conversion to a college—a lesser fate. This was the political climate in which many families abandoned the houses their families had owned for generations.

Town and Country Planning Act 1947

The apathy towards the nation's heritage continued after the passing of the

The apathy towards the nation's heritage continued after the passing of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947

The Town and Country Planning Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo. VI c. 51) was an Act of Parliament in the United Kingdom passed by the Labour government led by Clement Attlee. It came into effect on 1 July 1948, and along with the Town and Country Plannin ...

, even though this was the most comprehensive law pertaining to planning legislation in England. The 1947 Act went further than its predecessors in dealing with historic buildings, as it required owners of property to notify their local authority of intended alterations, and more significantly, demolitions. This caught any property which may have escaped official notice previously. Theoretically, it gave the local authority the opportunity to impose a preservation order on the property and prevent demolition. Under this law the Duke of Bedford was fined for demolishing half of Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

without notification, although it is inconceivable that the duke would have been able to demolish half of the huge house (much of it visible from a public highway) without attracting public attention until the demolition was complete.

Indifference on the part of local authorities and the public resulted in poor enforcement of the Act, and revealed the true root of the problem. When in 1956 Lord Lansdowne notified the "Ministry of Housing and Government" of his intention to demolish the greater part and corps de logis

In architecture, a ''corps de logis'' () is the principal block of a large, (usually classical), mansion or palace. It contains the principal rooms, state apartments and an entry.Curl, James Stevens (2006). ''Oxford Dictionary of Architecture ...

of Bowood

Bowood is a Grade I listed Georgian country house in Wiltshire, England, that has been owned for more than 250 years by the Fitzmaurice family. The house, with interiors by Robert Adam, stands in extensive grounds which include a garden designe ...

designed by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his ...

, no preservation society or historical group raised an objection (with the exception of James Lees-Milne

(George) James Henry Lees-Milne (6 August 1908 – 28 December 1997) was an English writer and expert on country houses, who worked for the National Trust from 1936 to 1973. He was an architectural historian, novelist and biographer. His extensi ...

, the noted biographer and historian of the English country house) and the demolition went ahead unchallenged. The mid-1950s, which should have been regulated by the above Acts, was the era in which most houses were legitimately destroyed, at an estimated rate of one every five days.

Town and Country Planning Act 1968

The demolition finally began to noticeably slow following the passing of the Town and Country Planning Act 1968. This Act compelled owners to seek and wait for permission to demolish a building, rather than merely notify the local authority. It also gave the local authority powers to immediately protect the building by issuing a "Building Preservation Notice", which in effect gave the structurelisted building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern I ...

status. Thus it was that 1968 became the last year that demolition ran into double figures.

The final and perhaps most important factor which secured Britain's heritage was a change in public opinion. This was in part brought about by the Destruction of the Country House exhibition held at London's Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (often abbreviated as the V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and nam ...

in 1974. The response to this highly publicised exhibition was very positive; for the first time the public, rather than a few intellectual bodies, became aware that country houses were an important part of the national heritage and worthy of preservation. Today, over 370,000 buildings are listed, which includes all buildings erected before 1700 and most constructed before 1840. After that date a building has to be of architectural or historical importance to be protected.

Re-evaluation of the country house

The unprecedented demolitions of the 20th century did not result in the complete demise of the country house, but rather in a consolidation of those that were most favoured by their owners. Many were the subject of comprehensive alteration and rearrangement of the interior, to facilitate a new way of life less dependent on vast numbers of servants. Largeservice wing

Servants' quarters are those parts of a building, traditionally in a private house, which contain the domestic offices and staff accommodation. From the late 17th century until the early 20th century, they were a common feature in many large ...

s, often 19th-century additions, were frequently demolished, as at Sandringham House

Sandringham House is a country house in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk, England. It is one of the royal residences of Charles III, whose grandfather, George VI, and great-grandfather, George V, both died there. The house stands in a estat ...

, or allowed to crumble, as was the case at West Wycombe Park.

From around 1900, interior woodwork, including complete panelled rooms and staircases and fittings such as chimneypiece

The fireplace mantel or mantelpiece, also known as a chimneypiece, originated in medieval times as a hood that projected over a fire grate to catch the smoke. The term has evolved to include the decorative framework around the fireplace, and ca ...

s, secured an avid market among rich Americans. In rare cases, complete houses were disassembled, stone by stone, and reassembled in the US; an example is Agecroft Hall

Agecroft Hall is a Tudor architecture, Tudor manor house and estate located at 4305 Sulgrave Road on the James River (Virginia), James River in the Windsor Farms neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia, United States. The manor house was built in the ...

, a Lancashire house sold at auction in 1925, dismantled, crated and shipped across the Atlantic, and then reassembled in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. The Carolean staircase from Cassiobury Park

Cassiobury Park is the principal public park in Watford, Hertfordshire, in England. It was created in 1909 from the purchase by Watford Borough Council of part of the estate of the Earls of Essex around Cassiobury House which was subsequentl ...

has come to rest in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

in New York, as have elements to reassemble "period rooms" de, including the rococo

Rococo (, also ), less commonly Roccoco or Late Baroque, is an exceptionally ornamental and theatrical style of architecture, art and decoration which combines asymmetry, scrolling curves, gilding, white and pastel colours, sculpted moulding, ...

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

ed plasterwork from the dining room of the Dashwood seat, Kirtlington Park

Kirtlington is a village and civil parish in Oxfordshire about west of Bicester. The parish includes the hamlet of Northbrook. The 2011 Census recorded the parish's population as 988. The parish measures nearly north–south and about east ...

; the tapestry room from Croome Court

Croome Court is a mid-18th-century Neo-Palladian mansion surrounded by extensive landscaped parkland at Croome D'Abitot, near Upton-upon-Severn in south Worcestershire, England. The mansion and park were designed by Lancelot "Capability" Brown fo ...

; and the dining room by Robert Adam

Robert Adam (3 July 17283 March 1792) was a British neoclassical architect, interior designer and furniture designer. He was the son of William Adam (1689–1748), Scotland's foremost architect of the time, and trained under him. With his ...

from Lansdowne House, London, where the incidence of lost great residences is higher, naturally enough, than anywhere in the countryside.

Stately home tourism

Many of Britain's greatest houses have frequently been open to the paying public. Well-heeled visitors could knock on the front door and a senior servant would give a guided tour for a small remuneration. In the early 19th century,Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

describes such a trip in ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

'', where Elizabeth Bennet and her aunt and uncle are shown around Mr Darcy's Pemberley

Pemberley is the fictional country estate owned by Fitzwilliam Darcy, the male protagonist in Jane Austen's 1813 novel ''Pride and Prejudice''. It is located near the fictional town of Lambton, and believed by some to be based on Lyme Park, south ...

by the housekeeper. Later in the century, on days when Belvoir Castle

Belvoir Castle ( ) is a faux historic castle and stately home in Leicestershire, England, situated west of the town of Grantham and northeast of Melton Mowbray. The Castle was first built immediately after the Norman Conquest of 1066 an ...

was open to the public, the 7th Duke of Rutland was reported by his granddaughter, the socialite Lady Diana

Diana, Princess of Wales (born Diana Frances Spencer; 1 July 1961 – 31 August 1997) was a member of the British royal family. She was the first wife of King Charles III (then Prince of Wales) and mother of Princes William and Harry. Her ac ...

, to assume a "look of pleasure and welcome."Vickers, Bath obituary. Here and elsewhere, however, that welcome did not extend to a tea room and certainly not to chimpanzees swinging through the shrubbery; that was all to come over 50 years later. At this time, admittance was granted in patrician fashion with all proceeds usually donated to a local charity.

In 1898, the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

(the National Trust) was founded as a charitable society principally for the preservation of landscapes of outstanding beauty or interest. During its infancy its focus gradually changed to include historic buildings. This was due in part to the millionaire philanthropist, Ernest Cook

Ernest Edward Cook (4 September 1865 – 14 March 1955) was an English philanthropist and businessman. He was a grandson of Thomas Cook, the travel entrepreneur.

Cook was born in Camberwell, London and educated at Mill Hill School, as were his t ...

. A man dedicated to preservation of country houses, he had purchased Montacute House

Montacute House is a late Elizabethan era, Elizabethan mansion with a garden in Montacute, South Somerset.

An example of English architecture during a period that was moving from the medieval Gothic to the Renaissance Classical, and one of fe ...

in 1931, one of England's most important Elizabethan mansions, which had been offered for sale with a "scrap value of £5,882". Cook presented the house to the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings

The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) (also known as Anti-Scrape) is an amenity society founded by William Morris, Philip Webb, and others in 1877 to oppose the destructive 'restoration' of ancient buildings occurring in ...

, which promptly passed it to the National Trust. It was one of the Trust's first great houses, and over the next 70 years was to be followed by over three hundred further nationally important houses which the Trust would administer and open to the public.

Following World War II, many owners of vast houses faced a dilemma; often they had already disposed of minor country residences to preserve the principal seat, and now that seat too was in jeopardy. Many considered passing their houses to the National Trust and subsequently received a visit from the Trust's representative, the diarist James Lees-Milne

(George) James Henry Lees-Milne (6 August 1908 – 28 December 1997) was an English writer and expert on country houses, who worked for the National Trust from 1936 to 1973. He was an architectural historian, novelist and biographer. His extensi ...

. He often had to choose between accepting a house and saving it, or declining it and sentencing it to dereliction and demolition. In his published memoirs he writes of the confusion many owners felt in what had become a world they no longer understood. Some were grateful to the Trust, some resented it, and others were openly hostile.

To some owners, the principal house was more than just a dwelling; built when the family was at the height of its power, wealth and glory, it represented the family's history and status. The family seat

A family seat or sometimes just called seat is the principal residence of the landed gentry and aristocracy. The residence usually denotes the social, economic, political, or historic connection of the family within a given area. Some families ...

was an integral part of the family's being and needed to be preserved and retained by the family, even if this meant "entering trade", a prospect which would have been unthinkable just a few years earlier. This turn of events had not been anticipated; Evelyn Waugh in his introduction to the 1959 second edition of ''Brideshead Revisited

''Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder'' is a novel by English writer Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1945. It follows, from the 1920s to the early 1940s, the life and romances of the protagonist Charles ...

'' explained he had not anticipated that Brideshead would in fact have been absorbed by the heritage industry; like the owners of many demolished 'stately homes' Waugh had assumed that such houses were doomed:

It was impossible to foresee, in the spring of 1944, the present cult of the English country house. It seemed then that the ancestral seats which were our chief national artistic achievement were doomed to decay and spoilation like the monasteries in the sixteenth century. So I piled it on rather, with passionate sincerity. Brideshead today would be open to trippers, its treasures rearranged by expert hands and the fabric better maintained than it was by Lord Marchmain.This can be exemplified by the business ventures executed by the

Marquess of Bath

Marquess of Bath is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain. It was created in 1789 for Thomas Thynne, 3rd Viscount Weymouth. The Marquess holds the subsidiary titles Baron Thynne, of Warminster in the County of Wiltshire, and Viscount Weymou ...

at Longleat House

Longleat is an English stately home and the seat of the Marquesses of Bath. A leading and early example of the Elizabethan prodigy house, it is adjacent to the village of Horningsham and near the towns of Warminster and Westbury in Wilts ...

. Reacquiring occupation of this enormous 16th-century mansion, in a state of poor repair, following requisition during World War II, the marquess was faced with death duties of £700,000. The marquess opened the house to the paying public and kept the proceeds himself to fund the mansion. In 1966, to keep attendance numbers high, the peer went a step further and introduced lions to the park, thus creating Britain's' first safari park

A safari park, sometimes known as a wildlife park, is a zoo-like commercial drive-in tourist attraction where visitors can drive their own vehicles or ride in vehicles provided by the facility to observe freely roaming animals.

A safari park ...

. After the initial opening of Longleat, the Dukes of Marlborough, Devonshire and Bedford opened Blenheim Palace

Blenheim Palace (pronounced ) is a country house in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, England. It is the seat of the Dukes of Marlborough and the only non- royal, non-episcopal country house in England to hold the title of palace. The palace, ...

, Chatsworth House

Chatsworth House is a stately home in the Derbyshire Dales, north-east of Bakewell and west of Chesterfield, England. The seat of the Duke of Devonshire, it has belonged to the Cavendish family since 1549. It stands on the east bank of the ...

and what remained of Woburn Abbey

Woburn Abbey (), occupying the east of the village of Woburn, Bedfordshire, England, is a country house, the family seat of the Duke of Bedford. Although it is still a family home to the current duke, it is open on specified days to visitors, ...

. With the example and precedent of "trade" set by those at the top of the aristocratic pyramid, within a few years hundreds of Britain's country houses were open two or three days a week to a public eager to see the rooms which a few years earlier their ancestors had cleaned. Others, such as Knebworth House

Knebworth House is an English country house in the parish of Knebworth in Hertfordshire, England. It is a Grade II* listed building. Its gardens are also listed Grade II* on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. In its surrounding park is t ...

, became venues for pop and rock festivals. By 1992, 600 "stately homes" were visited annually by 50 million members of the paying public. Stately homes were now big business, but opening a few rooms and novelties in the park alone was not going to fund the houses beyond the final decades of the twentieth century. Even during the stately home boom years of the 1960s and 1970s historic houses were still having their contents sold, being demolished or, if permission to demolish was not forthcoming, being left to dereliction and ruin.

By the early 1970s the demolition of great country houses began to slow. However, while the disappearance of the houses eased, the dispersal of the contents of many of these near redundant museums of social history did not, a fact highlighted in the early 1970s by the dispersal sale of Mentmore Towers