Denali National Park on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is an American

In 1906, conservationist

In 1906, conservationist

The name of Mount McKinley National Park was subject to local criticism from the beginning of the park. The word Denali means "the high one" in the native

The name of Mount McKinley National Park was subject to local criticism from the beginning of the park. The word Denali means "the high one" in the native

Martinson, Erica. '' Alaska Dispatch News'', 30 August 2015

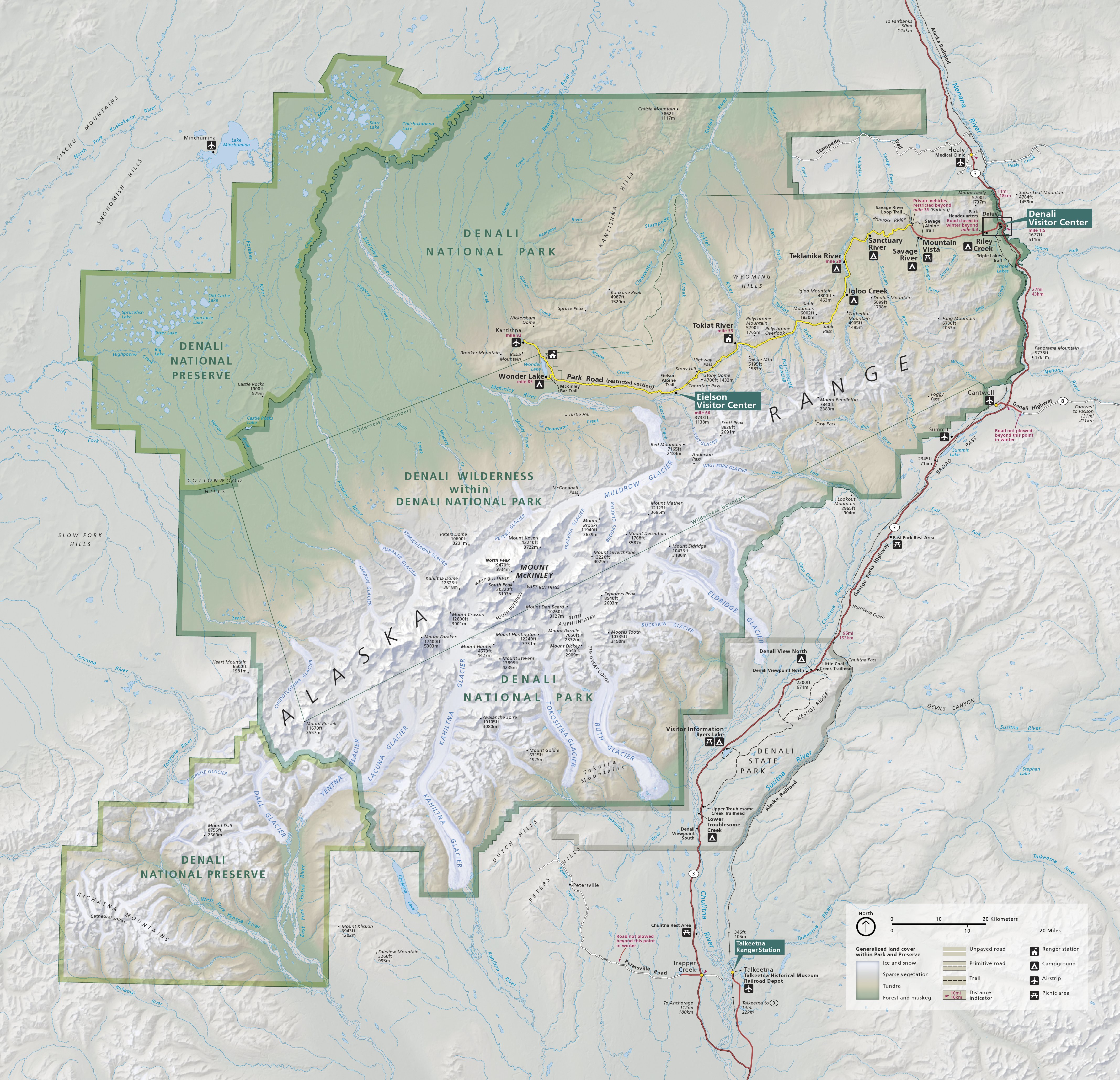

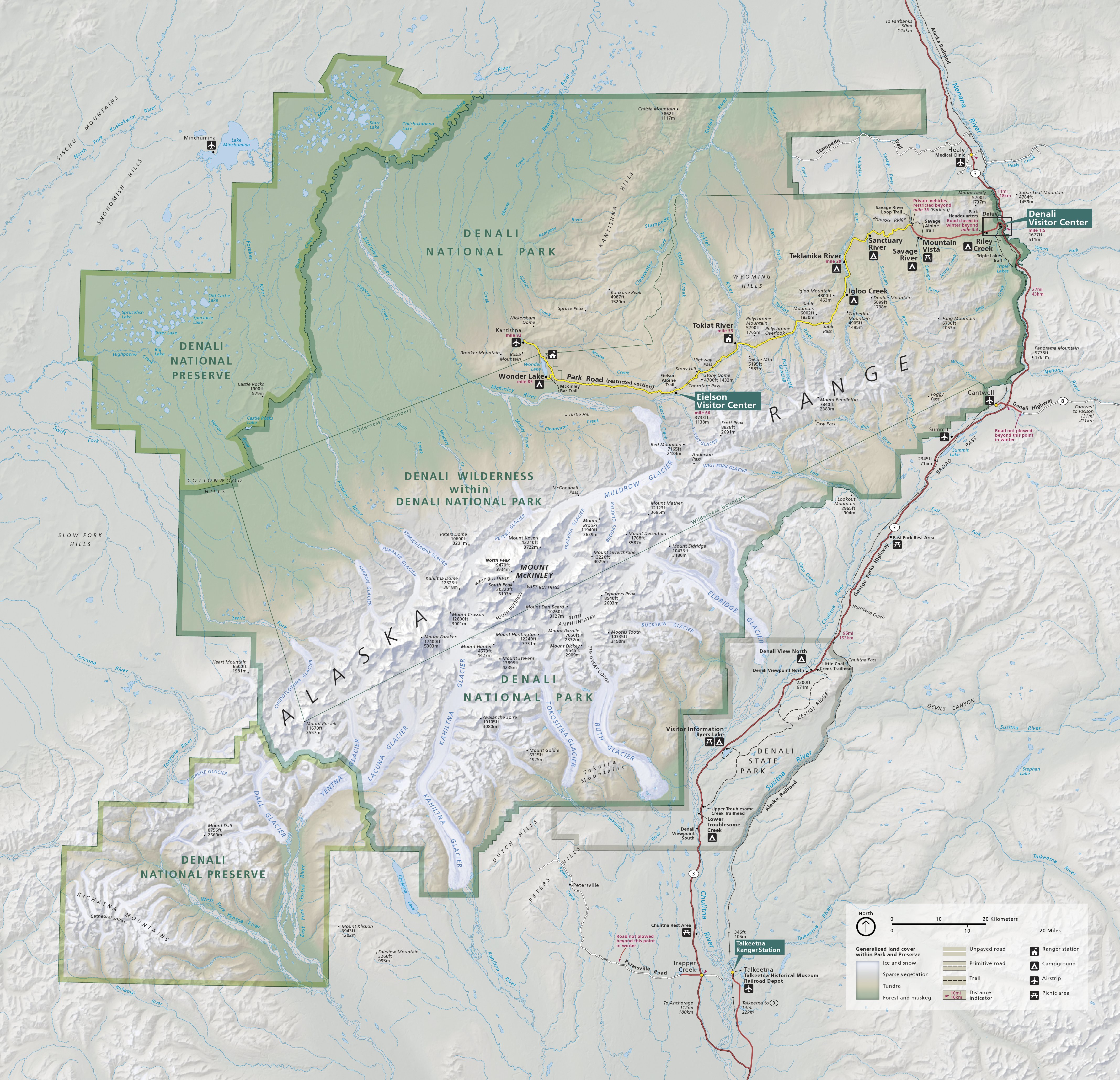

There are four camping areas located within the interior of the park (Sanctuary River, Teklanika River, Igloo Creek, and Wonder Lake). Camper buses provide transportation to these campgrounds, but only passengers camping in the park can use these particular buses. At mile marker 53 on road is the Toklat River Contact Station. All shuttle and tour buses make a stop at Toklat River. The contact station features restrooms, visitor information, and a small bookstore. Eielson Visitor Center is located four hours into the park on the road (at mile marker 66). It features restrooms, daily ranger-led programs during the summer, and on clear days, views of Denali and the Alaska Range. Wonder Lake and Kantishna are a six-hour bus ride from the Visitors Center. During the winter, only the portion of Denali Park Road near the Visitors Center remains open.

Kantishna features five lodges: the Denali Backcountry Lodge, Kantishna Roadhouse, Skyline Lodge, Camp Denali, and North Face Lodge. Visitors can bypass the six-hour bus ride and charter an air taxi flight to the Kantishna Airport. The Kantishna resorts have no TVs, and there is no cell phone service in the area. Lodging with services can be found in McKinley Park, one mile north of the park entrance on the George Parks Highway. Many hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and convenience stores are located in Denali Park.

While the main park road goes straight through the middle of the Denali Wilderness, the national preserve and portions of the park not designated

There are four camping areas located within the interior of the park (Sanctuary River, Teklanika River, Igloo Creek, and Wonder Lake). Camper buses provide transportation to these campgrounds, but only passengers camping in the park can use these particular buses. At mile marker 53 on road is the Toklat River Contact Station. All shuttle and tour buses make a stop at Toklat River. The contact station features restrooms, visitor information, and a small bookstore. Eielson Visitor Center is located four hours into the park on the road (at mile marker 66). It features restrooms, daily ranger-led programs during the summer, and on clear days, views of Denali and the Alaska Range. Wonder Lake and Kantishna are a six-hour bus ride from the Visitors Center. During the winter, only the portion of Denali Park Road near the Visitors Center remains open.

Kantishna features five lodges: the Denali Backcountry Lodge, Kantishna Roadhouse, Skyline Lodge, Camp Denali, and North Face Lodge. Visitors can bypass the six-hour bus ride and charter an air taxi flight to the Kantishna Airport. The Kantishna resorts have no TVs, and there is no cell phone service in the area. Lodging with services can be found in McKinley Park, one mile north of the park entrance on the George Parks Highway. Many hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and convenience stores are located in Denali Park.

While the main park road goes straight through the middle of the Denali Wilderness, the national preserve and portions of the park not designated

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in the central area of the Alaska Range, a mountain chain extending across Alaska. Its best-known geologic feature is

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in the central area of the Alaska Range, a mountain chain extending across Alaska. Its best-known geologic feature is  Some of the youngest rocks in the park include the Kahiltna terrane, which is a

Some of the youngest rocks in the park include the Kahiltna terrane, which is a

Glaciers cover about 16% of the 6 million acres of Denali National Park and Preserve. Measurements indicate that

Glaciers cover about 16% of the 6 million acres of Denali National Park and Preserve. Measurements indicate that  Large amounts of rock debris are carried on, in, and beneath the ice as the glaciers move downslope. Lateral

Large amounts of rock debris are carried on, in, and beneath the ice as the glaciers move downslope. Lateral

Thermal expansion and contraction cause permafrost cracking. In the summer water fills these cracks and forms veins called ice wedges. These wedges enlarge with seasonal freezing/thawing cycles. Some ice wedges buried for centuries are revealed during excavations or landslides.

Thermal expansion and contraction cause permafrost cracking. In the summer water fills these cracks and forms veins called ice wedges. These wedges enlarge with seasonal freezing/thawing cycles. Some ice wedges buried for centuries are revealed during excavations or landslides.

The

The  Denali is home to a variety of North American birds and mammals, including an estimated 300-350

Denali is home to a variety of North American birds and mammals, including an estimated 300-350  Ten species of fish, including

Ten species of fish, including

A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, Alaska

National Park Service *Collier, Michael (2007), ''The Geology of Denali National Park and Preserve''. Alaska Geographic. *Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (2004). ''Geology of the National Parks'', 6th ed. Kendall/Hunt. *Murie, Adolph (1961), ''A Naturalist in Alaska''. Devin-Adair. *Murie, Adolph (1981)

National Park Service *Murie, Adolph (1944)

''Fauna of the National Parks of the United States Series No. 5'', National Park Service *Norris, Frank (2006)

''Crown Jewel of the North:An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve''

Volume 1, National Park Service (10 MB download) *Norris, Frank (2006)

''Crown Jewel of the North:An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve''

Volume 2, National Park Service (80 MB download) *Scoggins, Dow (2004), ''Discovering Denali: A Complete Reference Guide to Denali National Park and Mount McKinley, Alaska''. iUniverse Star. * Sheldon, Charles (1930), ''The Wilderness of Denali''. Derrydale Press (reprint), *Waits, Ike (2010), ''Denali National Park, Alaska: Guide to Hiking, Photography and Camping''. Wild Rose Guidebooks.

-

NPS education packet''Small Mammal Population in Mount McKinley National Park, Alaska'' Manuscript

at Dartmouth College Library * *

national park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

and preserve

The word preserve may refer to:

Common uses

* Fruit preserves, a type of sweet spread or condiment

* Nature reserve, an area of importance for wildlife, flora, fauna or other special interest, usually protected

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the ...

, the highest mountain in North America. The park and contiguous preserve encompass which is larger than the state of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. On December 2, 1980, Denali Wilderness was established within the park. Denali's landscape is a mix of forest at the lowest elevations, including deciduous taiga

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, sp ...

, with tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

at middle elevations, and glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s, snow, and bare rock at the highest elevations. The longest glacier is the Kahiltna Glacier

Kahiltna Glacier is the longest glacier of the Alaska Range in the U.S. state of Alaska. It starts on the southwest slope of Denali near Kahiltna Pass (elevation ). Its main channel runs almost due south between Mount Foraker to the west and ...

. Wintertime activities include dog sled

A dog sled or dog sleigh is a sled pulled by one or more sled dogs used to travel over ice and through snow. Numerous types of sleds are used, depending on their function. They can be used for dog sled racing. Traditionally in Greenland and th ...

ding, cross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing where skiers rely on their own locomotion to move across snow-covered terrain, rather than using ski lifts or other forms of assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreatio ...

, and snowmobiling

A snowmobile, also known as a Ski-Doo, snowmachine, sled, motor sled, motor sledge, skimobile, or snow scooter, is a motorized vehicle designed for winter travel and recreation on snow. It is designed to be operated on snow and ice and does not ...

. The park received 594,660 recreational visitors in 2018.

History

Prehistory and protohistory

Human habitation in the Denali Region extends to more than 11,000 years before the present, with documented sites just outside park boundaries dated to more than 8,000 years before the present. However, relatively few archaeological sites have been documented within the park boundaries, owing to the region's high elevation, with harsh winter conditions and scarce resources compared to lower elevations in the area. The oldest site within park boundaries is the Teklanika River site, dated to about 7130 BC. More than 84 archaeological sites have been documented within the park. The sites are typically characterized as hunting camps rather than settlements and provide little cultural context. The presence ofAthabaskan

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific ...

peoples in the region is dated to 1,500 - 1,000 years before present on linguistic and archaeological evidence, while researchers have proposed that Athabaskans may have inhabited the area for thousands of years before then. The principal groups in the park area in the last 500 years include the Koyukon

The Koyukon (russian: Коюконы) are an Alaska Native Athabascan people of the Athabascan-speaking ethnolinguistic group. Their traditional territory is along the Koyukuk and Yukon rivers where they subsisted for thousands of years b ...

, Tanana and Dena'ina people.Norris, Vol. 1, pp. 2-3

Establishment of the park

In 1906, conservationist

In 1906, conservationist Charles Alexander Sheldon

Charles Alexander Sheldon (17 October 1867 – 21 September 1928) was an American conservationist and the "Father of Denali National Park". He had a special interest in the bighorn sheep and spent time hunting with the Seri Indians in Sonora, ...

conceived the idea of preserving the Denali region as a national park. He presented the plan to his co-members of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United Sta ...

. They decided that the political climate at the time was unfavorable for congressional action and that the best hope of success rested on the approval and support of the Alaskans themselves. Sheldon wrote, "The first step was to secure the approval and cooperation of the delegate who represented Alaska in Congress."

In October 1915, Sheldon took up the matter with Dr. E. W. Nelson of the Biological Survey at Washington, D.C., and with George Bird Grinnell

George Bird Grinnell (September 20, 1849 – April 11, 1938) was an American anthropologist, historian, naturalist, and writer. Grinnell was born in Brooklyn, New York, and graduated from Yale University with a B.A. in 1870 and a Ph.D. in 1880. ...

, with the purpose to introduce a suitable bill in the coming session of Congress. The matter was then taken to the Game Committee of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United Sta ...

and, after a full discussion, it received the committee's full endorsement.

On December 3, 1915, the plan was presented to Alaska's delegate, James Wickersham, who after some deliberation gave his approval. The plan then went to the executive committee of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United Sta ...

and, on December 15, 1915, it was unanimously accepted. The plan was thereupon endorsed by the club and presented to Stephen Mather, Assistant Secretary of the Interior in Washington, D.C., who immediately approved it.

The bill was introduced in April 1916, by Delegate Wickersham in the House and by Senator Key Pittman of Nevada in the Senate. Much lobbying took place the following year, and on February 19, 1917, the bill passed. On February 26, 1917, 11 years from its conception, the bill was signed in legislation by the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

, thereby creating Mount McKinley National Park.

A portion of Denali, excluding the summit, was included in the original park boundary. The boundary was expanded in 1922 and again in 1932 and 1947 to include the area of the hotel and railroad.

On Thanksgiving Day in 1921, the Mount McKinley Park Hotel opened. In July 1923, President Warren Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th president of the United States, serving from 1921 until his death in 1923. A member of the Republican Party, he was one of the most popular sitting U.S. presidents. A ...

stopped at the hotel, on a tour of the length of the Alaska Railroad

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S. ...

, during which he drove a golden spike signaling its completion at Nenana. The hotel was the first thing visitors saw stepping down from the train. The flat-roofed, two-story log building featured exposed balconies, glass windows, and electric lights. Inside were two dozen guest rooms, a shop, a lunch counter, a kitchen, and a storeroom. By the 1930s, there were reports of lice, dirty linen, drafty rooms, and marginal food, which led to the hotel eventually closing. After being abandoned for many years, the hotel was destroyed in 1972 by a fire.

The Park Road was completed in 1938 after 17 years of construction.

There was no road access to the park entrance until 1957 when the Denali Highway

Denali Highway (Alaska Route 8) is a lightly traveled, mostly gravel highway in the U.S. state of Alaska. It leads from Paxson on the Richardson Highway to Cantwell on the Parks Highway. Opened in 1957, it was the first road access to Denali Na ...

opened; park attendance greatly expanded: there were 5,000 visitors in 1956 and 25,000 visitors by 1958. In 1971, the George Parks Highway

The George Parks Highway (numbered Interstate A-4 and signed Alaska Route 3), usually called simply the Parks Highway, runs 323 miles (520 km) from the Glenn Highway 35 miles (56 km) north of Anchorage to Fairbanks in the Alaska Inte ...

, under piecemeal construction for several years, was completed, providing direct highway connections to Anchorage and Fairbanks. Visitation doubled to 88,000 from 1971 to 1972.

In 1967, the park was the site of one of the deadliest mountaineering accidents in the United States with the Mount McKinley disaster, where seven climbers died in an intense blizzard

A blizzard is a severe snowstorm characterized by strong sustained winds and low visibility, lasting for a prolonged period of time—typically at least three or four hours. A ground blizzard is a weather condition where snow is not falling ...

on Denali. The Park Service debated closing the mountain to climbing in the wake of the accident, but ultimately it remained open.

The park was designated an international biosphere reserve in 1976. A surrounding Denali National Monument was proclaimed by President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

on December 1, 1978, which was combined with the park in 1980.

Naming dispute

The name of Mount McKinley National Park was subject to local criticism from the beginning of the park. The word Denali means "the high one" in the native

The name of Mount McKinley National Park was subject to local criticism from the beginning of the park. The word Denali means "the high one" in the native Athabaskan

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific ...

language and refers to the mountain itself. The mountain was named after newly elected US president William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in t ...

in 1897 by local prospector William A. Dickey. The United States government formally adopted the name Mount McKinley after President Wilson signed the bill creating Mount McKinley National Park into effect in 1917. In 1980, Mount McKinley National Park was combined with Denali National Monument, and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) is a United States federal law signed by President Jimmy Carter on December 2, 1980. ANILCA provided varying degrees of special protection to over of land, including national parks, n ...

named the combined unit the Denali National Park and Preserve. At that time the Alaska state Board of Geographic Names changed the name of the mountain to Denali. However, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names did not recognize the change and continued to denote the official name as Mount McKinley. This situation lasted until August 30, 2015, when President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

directed Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry

An ...

Sally Jewell

Sarah Margaret "Sally" Roffey Jewell (born February 21, 1956) is a British-American businessperson who served as the 51st United States secretary of the interior in the Obama administration from 2013 to 2017.

Jewell was born in London and move ...

to rename the mountain to Denali, using statutory authority to act on requests when the Board of Geographic Names does not do so in a "reasonable" period.McKinley no more: North America's tallest peak to be renamed DenaliMartinson, Erica. '' Alaska Dispatch News'', 30 August 2015

1990s

In 1992,Christopher McCandless

Christopher Johnson McCandless (; February 12, 1968 – August 1992), also known by his pseudonym "Alexander Supertramp", was an American adventurer who sought an increasingly nomadic lifestyle as he grew up. McCandless is the subject of '' In ...

ventured into the Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

n wilderness and settled in an abandoned bus in the park on the Stampede Trail

The Stampede Trail is a remote road and trail located in the Denali Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Apart from a paved or maintained gravel road for between Eight Mile Lake and the trail's eastern end, the route consists of a primitive an ...

at , near Lake Wentitika. He carried little food or equipment, and hoped to live simply for a time in solitude. Almost four months later, McCandless' starved remains were found, weighing only . His story has been widely publicized via articles, books, and films, and the bus where his remains were found has become a shrine attracting people from around the world.

On September 24, 2020, the Museum of The North at the University of Alaska

The University of Alaska System is a system of public universities in the U.S. state of Alaska. It was created in 1917 and comprises three separately accredited universities on 19 campuses. The system serves nearly 30,000 full- and part-time stu ...

(Fairbanks

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the p ...

) announced it became the permanent home of McCandless' 'Magic Bus 142' where it will be restored and an outdoor exhibit will be created.

2000s

On November 5, 2012, theUnited States Mint

The United States Mint is a bureau of the Department of the Treasury responsible for producing coinage for the United States to conduct its trade and commerce, as well as controlling the movement of bullion. It does not produce paper money; tha ...

released the 15th of its America the Beautiful Quarters series, which honors Denali National Park. The coin's reverse side features a Dall sheep with Denali in the background.

In September 2013, President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

signed the Denali National Park Improvement Act into law. The statute allows the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is one of the executive departments of the U.S. federal government headquartered at the Main Interior Building, located at 1849 C Street NW in Washington, D.C. It is responsible for the ma ...

to "issue permits for microhydroelectric projects in the Kantishna Hills area of the Denali National Park and Preserve in Alaska"; it authorizes the Department of the Interior and a company called Doyon Tourism, Inc. to exchange some land in the area; it authorizes the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational properti ...

(NPS) to "issue permits to construct a natural gas pipeline in the Denali National Park"; and it renames the existing Talkeetna Ranger Station the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station. The National Parks Conservation Association supported the bill because the legislation "takes a thoughtful approach to protecting roadless Alaska, promoting renewable energy development, and honoring native Alaskans."

Geography

Denali National Park and Preserve includes the central, highest portion of theAlaska Range

The Alaska Range is a relatively narrow, 600-mile-long (950 km) mountain range in the southcentral region of the U.S. state of Alaska, from Lake Clark at its southwest endSources differ as to the exact delineation of the Alaska Range. ThBo ...

, together with many of the glaciers and glacial valleys running southwards out of the range. To the north the park and preserve encompass the valleys of the McKinley, Toklat, and Foraker Rivers, as well as the Kantishna and Wyoming Hills. The George Parks Highway

The George Parks Highway (numbered Interstate A-4 and signed Alaska Route 3), usually called simply the Parks Highway, runs 323 miles (520 km) from the Glenn Highway 35 miles (56 km) north of Anchorage to Fairbanks in the Alaska Inte ...

runs along the eastern edge of the park, crossing the Alaska Range at the divide between the valleys of the Chultina River and the Nenana River. The entrance to the park is about south of Healy. The Denali Visitor Center and the park headquarters are located just inside the entrance. The park road parallels the Alaska Range for , ending at Kantishna. Preserve lands are located on the west side of the park, with one parcel encompassing areas of lakes in the Highpower Creek and Muddy River areas, and the second preserve area covering the southwest end of the high Alaska Range around Mount Dall

Mount Dall is a mountain in the Alaska Range, in Denali National Park and Preserve, southwest of Denali. Mount Dall was named in 1902 by A.H. Brooks of the U.S. Geological Survey after naturalist and Alaska explorer William Healey Dall.

See also ...

. In contrast to the park, where hunting is prohibited or restricted to subsistence hunting by local residents, sport hunting is allowed in the preserve lands. Nikolai, Telida, Lake Minchumina, and Cantwell residents are authorized to hunt inside the park because large portions of these communities historically hunted in the area for subsistence purposes.

Vehicle access

The park is serviced by the long Denali Park Road, which begins at theGeorge Parks Highway

The George Parks Highway (numbered Interstate A-4 and signed Alaska Route 3), usually called simply the Parks Highway, runs 323 miles (520 km) from the Glenn Highway 35 miles (56 km) north of Anchorage to Fairbanks in the Alaska Inte ...

and continues to the west, ending at Kantishna. Located within the park, the Denali Bus Depot (which houses a small gift shop, a coffee stand, and an information desk) is the main location to arrange a bus trip into the park or reserve/check-in for a campground site. All shuttle buses depart from here, as do some tours. The Denali Visitor Center is at mile marker 1.5 on the park road and is the main source of visitor information. Most ranger-led programs begin at the Denali Visitor Center. Other features include an exhibit hall. Within a short walking distance from the Visitor Center are a restaurant, a bookstore, the Murie Science and Learning Center, the Denali National Park railroad depot, and the McKinley National Park Airport.

The Denali Park Road runs north of and roughly parallel to the imposing Alaska Range

The Alaska Range is a relatively narrow, 600-mile-long (950 km) mountain range in the southcentral region of the U.S. state of Alaska, from Lake Clark at its southwest endSources differ as to the exact delineation of the Alaska Range. ThBo ...

. Only a small fraction of the road is paved because permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

and the freeze-thaw cycle would create a high cost for maintaining a paved road. The first of the road are available to private vehicles, allowing easy access to the Riley Creek and Savage River campgrounds. Private vehicle access is prohibited beyond the Savage River Bridge. There is a turnaround for motorists at this point, as well as a nearby parking area for those who wish to hike the Savage River Loop Trail. Beyond this point, visitors must access the interior of the park through tour/shuttle buses.

The road has been impacted by the Pretty Rocks landslide at Polychrome Pass at Mile 45.4. NPS believes the landslide has been active since before the road was built, but only required moderate maintenance every 2–3 years. Beginning in 2014, the landslide accelerated considerably, requiring the road crew to spread 100 truckloads of gravel per week to keep the road passable until August 2021, when the park decided to close the road beyond Mile 45 until 2023 at the earliest. After studying potential solutions including re-routing the road, park officials decided to construct a bridge over the landslide which will cost $55 million and is expected to begin in 2022 and take two or three seasons to complete.

The tours travel from the initial boreal forest

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruc ...

s through tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

to the Toklat River or Kantishna. Several portions of the road run alongside sheer cliffs

In geography and geology, a cliff is an area of rock which has a general angle defined by the vertical, or nearly vertical. Cliffs are formed by the processes of weathering and erosion, with the effect of gravity. Cliffs are common on coa ...

that drop hundreds of feet at the edges. There are no guardrails. As a result of the danger involved, and because most of the gravel

Gravel is a loose aggregation of rock fragments. Gravel occurs naturally throughout the world as a result of sedimentary and erosive geologic processes; it is also produced in large quantities commercially as crushed stone.

Gravel is classifi ...

road is only one lane wide, drivers must be trained in procedures for navigating the sharp mountain curves and yielding the right-of-way

Right of way is the legal right, established by grant from a landowner or long usage (i.e. by prescription), to pass along a specific route through property belonging to another.

A similar ''right of access'' also exists on land held by a gov ...

to opposing buses and park vehicles.

There are four camping areas located within the interior of the park (Sanctuary River, Teklanika River, Igloo Creek, and Wonder Lake). Camper buses provide transportation to these campgrounds, but only passengers camping in the park can use these particular buses. At mile marker 53 on road is the Toklat River Contact Station. All shuttle and tour buses make a stop at Toklat River. The contact station features restrooms, visitor information, and a small bookstore. Eielson Visitor Center is located four hours into the park on the road (at mile marker 66). It features restrooms, daily ranger-led programs during the summer, and on clear days, views of Denali and the Alaska Range. Wonder Lake and Kantishna are a six-hour bus ride from the Visitors Center. During the winter, only the portion of Denali Park Road near the Visitors Center remains open.

Kantishna features five lodges: the Denali Backcountry Lodge, Kantishna Roadhouse, Skyline Lodge, Camp Denali, and North Face Lodge. Visitors can bypass the six-hour bus ride and charter an air taxi flight to the Kantishna Airport. The Kantishna resorts have no TVs, and there is no cell phone service in the area. Lodging with services can be found in McKinley Park, one mile north of the park entrance on the George Parks Highway. Many hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and convenience stores are located in Denali Park.

While the main park road goes straight through the middle of the Denali Wilderness, the national preserve and portions of the park not designated

There are four camping areas located within the interior of the park (Sanctuary River, Teklanika River, Igloo Creek, and Wonder Lake). Camper buses provide transportation to these campgrounds, but only passengers camping in the park can use these particular buses. At mile marker 53 on road is the Toklat River Contact Station. All shuttle and tour buses make a stop at Toklat River. The contact station features restrooms, visitor information, and a small bookstore. Eielson Visitor Center is located four hours into the park on the road (at mile marker 66). It features restrooms, daily ranger-led programs during the summer, and on clear days, views of Denali and the Alaska Range. Wonder Lake and Kantishna are a six-hour bus ride from the Visitors Center. During the winter, only the portion of Denali Park Road near the Visitors Center remains open.

Kantishna features five lodges: the Denali Backcountry Lodge, Kantishna Roadhouse, Skyline Lodge, Camp Denali, and North Face Lodge. Visitors can bypass the six-hour bus ride and charter an air taxi flight to the Kantishna Airport. The Kantishna resorts have no TVs, and there is no cell phone service in the area. Lodging with services can be found in McKinley Park, one mile north of the park entrance on the George Parks Highway. Many hotels, restaurants, gift shops, and convenience stores are located in Denali Park.

While the main park road goes straight through the middle of the Denali Wilderness, the national preserve and portions of the park not designated wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

are even more inaccessible. No roads are extending out to the preserve areas, which are on the northwest and southwest ends of the park. The far north of the park, characterized by hills and rivers, is accessed from the east by the Stampede Trail

The Stampede Trail is a remote road and trail located in the Denali Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Apart from a paved or maintained gravel road for between Eight Mile Lake and the trail's eastern end, the route consists of a primitive an ...

, a dirt road that effectively stops at the park boundary near the former location of the '' Into the Wild'' bus. The rugged south portion of the park, characterized by large glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

-filled canyons

A canyon (from ; archaic British English spelling: ''cañon''), or gorge, is a deep cleft between escarpments or cliffs resulting from weathering and the erosive activity of a river over geologic time scales. Rivers have a natural tendency to cu ...

, is accessed by Petersville Road, a dirt road that stops about outside the park. The mountains can be accessed most easily by air taxis that land on the glaciers. Kantishna can also be reached by air taxi via the Purkeypile Airport, which is just outside the park boundary.

Visitors who want to climb Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the ...

need to obtain a climbing permit first and go through an orientation as well. These can be found at the Walter Harper Talkeetna Ranger Station in Talkeetna, Alaska, about south of the entrance to Denali National Park and Preserve. This center serves as the center of mountaineering operations. Hours of operation vary, check the National Park

A national park is a natural park in use for conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state declares or owns. Although individual ...

website for specific details.

Savage River, Eielson Visitor Center, and Wonder Lake offer maintained hiking

Hiking is a long, vigorous walk, usually on trails or footpaths in the countryside. Walking for pleasure developed in Europe during the eighteenth century.AMATO, JOSEPH A. "Mind over Foot: Romantic Walking and Rambling." In ''On Foot: A Histor ...

trails, and at Riley Creek, there are several maintained trails including a hike up to Mt. Healy Overlook trail. The park also encourages off-trail hiking.

Wilderness

The Denali Wilderness is a wilderness area within Denali National Park that protects the higher elevations of the centralAlaska Range

The Alaska Range is a relatively narrow, 600-mile-long (950 km) mountain range in the southcentral region of the U.S. state of Alaska, from Lake Clark at its southwest endSources differ as to the exact delineation of the Alaska Range. ThBo ...

, including Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the ...

. The wilderness comprises about one-third of the current national park and preserve— that correspond with the former park boundaries before 1980.

Geology

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in the central area of the Alaska Range, a mountain chain extending across Alaska. Its best-known geologic feature is

Denali National Park and Preserve is located in the central area of the Alaska Range, a mountain chain extending across Alaska. Its best-known geologic feature is Denali

Denali (; also known as Mount McKinley, its former official name) is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. With a topographic prominence of and a topographic isolation of , Denali is the ...

, formerly known as Mount McKinley. Its elevation of makes it the highest mountain in North America. Its vertical relief (distance from base to peak) of is the highest of any mountain in the world. The mountain is still gaining about in height each year due to the continued convergence of the North American

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the ...

and Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and I ...

s. The mountain is primarily made of granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies un ...

, a hard rock that does not erode easily; this is why it has retained such a great height rather than being eroded.

The park area is characterized by collision tectonics: over the past millions of years, exotic terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its ow ...

s in the Pacific Ocean have been moving toward the North American landmass and accreting, or attaching, to the area that now makes up Alaska. The oldest rocks in the park are part of the Yukon-Tanana terrane. They originated from ocean sediments deposited between 400 million and 1 billion years ago. The original rocks have been affected by the processes of regional metamorphism, folding, and faulting to form rocks such as schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

, quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tec ...

, phyllite

Phyllite ( ) is a type of foliated metamorphic rock created from slate that is further metamorphosed so that very fine grained white mica achieves a preferred orientation.Stephen Marshak ''Essentials of Geology'', 3rd ed. It is primarily compo ...

, slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

, marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

, and limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

. The next oldest group of rocks is the Farewell terrane. It is composed of rocks from the Paleozoic era (250-500 million years old). The sediments that make up these rocks were deposited in a variety of marine environments, ranging from deep ocean basins to continental shelf areas. The abundant marine fossils are evidence that around 380 million years ago, this area had a warm, tropical climate. The Pingston, McKinley, and Chulitna terranes are the next oldest; they were deposited in the Mesozoic era

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

. The rock types include marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

, chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a ...

, limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especiall ...

, and sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

. There are intrusions of igneous

Igneous rock (derived from the Latin word ''ignis'' meaning fire), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rock is formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or ...

rocks, such as gabbro

Gabbro () is a phaneritic (coarse-grained), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling of magnesium-rich and iron-rich magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ...

, diabase

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-grain ...

, and diorite

Diorite ( ) is an intrusive igneous rock formed by the slow cooling underground of magma (molten rock) that has a moderate content of silica and a relatively low content of alkali metals. It is intermediate in composition between low-sil ...

. Special features include pillow basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low- viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron ( mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More th ...

s, which are formed when molten lava flows into water and a hard outer crust forms, making a puffy, pillow-shaped feature; as well as an ophiolite

An ophiolite is a section of Earth's oceanic crust and the underlying upper mantle that has been uplifted and exposed above sea level and often emplaced onto continental crustal rocks.

The Greek word ὄφις, ''ophis'' (''snake'') is found ...

sequence, which is a distinct sequence of rocks indicating that a section of the oceanic crust has been uplifted and thrust onto a continental area.

Some of the youngest rocks in the park include the Kahiltna terrane, which is a

Some of the youngest rocks in the park include the Kahiltna terrane, which is a flysch

Flysch () is a sequence of sedimentary rock layers that progress from deep-water and turbidity flow deposits to shallow-water shales and sandstones. It is deposited when a deep basin forms rapidly on the continental side of a mountain building epi ...

sequence (a sedimentary rock sequence deposited in a marine environment during the early stages of mountain building) formed about 100 million years ago, during late Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 145 to 66 million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era, as well as the longest. At around 79 million years, it is the longest geological period of ...

time. Another rock sequence is the McKinley Intrusive Sequence, which includes Denali. The Cantwell Volcanics include basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the surface of a rocky planet or moon. More than 90 ...

and rhyolite

Rhyolite ( ) is the most silica-rich of volcanic rocks. It is generally glassy or fine-grained (aphanitic) in texture, but may be porphyritic, containing larger mineral crystals ( phenocrysts) in an otherwise fine-grained groundmass. The miner ...

flows, as well as ash deposits. An example can be seen at Polychrome Pass in the park.Harris, A.G., Tuttle, E., Tuttle S.D. Geology of National Parks. 6th ed. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company 2004.

Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

fossils include fossil trackway

A fossil track or ichnite (Greek "''ιχνιον''" (''ichnion'') – a track, trace or footstep) is a fossilized footprint. This is a type of trace fossil. A fossil trackway is a sequence of fossil tracks left by a single organism. Over the yea ...

s from therizinosaurid

Therizinosauridae (meaning 'scythe lizards')Translated paper

is a family of derived (advanc ...

s and is a family of derived (advanc ...

hadrosaurids

Hadrosaurids (), or duck-billed dinosaurs, are members of the ornithischian family Hadrosauridae. This group is known as the duck-billed dinosaurs for the flat duck-bill appearance of the bones in their snouts. The ornithopod family, which includ ...

in the Cantwell Formation indicate the area was once an immigration point for dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s traveling between Asia and North America during the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', ...

period. Studies of fossil plants from the same formation indicate the area was wet, with marshes and ponds throughout the region.

Denali National Park and Preserve are located in an area of intense tectonic activity: the Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and I ...

is subducting under the North American plate

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate covering most of North America, Cuba, the Bahamas, extreme northeastern Asia, and parts of Iceland and the Azores. With an area of , it is the Earth's second largest tectonic plate, behind the Paci ...

, creating the Denali fault system, which is a right-lateral strike-slip fault

In geology, a fault is a planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust result from the action of plate tectoni ...

over long. This is a part of the larger fault system which includes the famous San Andreas Fault

The San Andreas Fault is a continental transform fault that extends roughly through California. It forms the tectonic boundary between the Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, and its motion is right-lateral strike-slip (horizontal) ...

of California. Over 600 earthquakes occur in the park each year, helping seismologists to understand this fault system. Most of these earthquakes are too small to be felt, although two large earthquakes did occur in 2002. On October 23, 2002, a magnitude 6.7 earthquake occurred in the park, and on November 3, 2002, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake occurred. These earthquakes did not cause a significant loss of life or property, since the area is very sparsely populated, but they did trigger thousands of landslides.National Park Service: Denali National Park and Preserve. Denali Rocks! The Geology of Denali National Park and Preserve: A Curriculum Guide for Grades 6-8. 2011.

Glaciers

Glaciers cover about 16% of the 6 million acres of Denali National Park and Preserve. Measurements indicate that

Glaciers cover about 16% of the 6 million acres of Denali National Park and Preserve. Measurements indicate that glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s in the park are losing about 6.6 ft (2 m) of vertical water equivalency each year. There are more extensive glaciers on the southeastern side of the range because more snow is dropped on this side from the moisture-bearing winds from the Gulf of Alaska. The 5 largest south-facing glaciers are Yentna ( long), Kahiltna (), Tokositna (), Ruth (), and Eldrige (). The Ruth glacier is thick. However, the largest glacier, Muldrow Glacier

Muldrow Glacier, also known as McKinley Glacier, is a large glacier in Denali National Park and Preserve in the U.S. state of Alaska. Native names for the glacier include, Henteel No' Loo' and Henteel No' Loot.

The glacier originates from the G ...

( long), is located on the north side. Nonetheless, the northern side has smaller and shorter glaciers overall. Muldrow glacier has "surged" twice in the last hundred years. Surging means that it has moved forward for a short time at greatly increased speed, due to a build-up of water between the bottom of the glacier and the bedrock channel floating on the ice (due to hydrostatic pressure).

At the upper ends of Denali's glaciers are steep-walled semicircular basins called cirque

A (; from the Latin word ') is an amphitheatre-like valley formed by glacial erosion. Alternative names for this landform are corrie (from Scottish Gaelic , meaning a pot or cauldron) and (; ). A cirque may also be a similarly shaped landf ...

s. Cirques form from freeze-thaw cycles of meltwater in the rocks above the glacier and glacial erosion and mass wasting occur under the glacier. As cirques on the opposite sides of a ridge are cut deeper into the divide, they form a narrow, sharp, serrated ridge called an arête

An arête ( ) is a narrow ridge of rock which separates two valleys. It is typically formed when two glaciers erode parallel U-shaped valleys. Arêtes can also form when two glacial cirques erode headwards towards one another, although frequ ...

. As the arête wears away from glacial ice erosion, the low point between cirques is called a col

In geomorphology, a col is the lowest point on a mountain ridge between two peaks.Whittow, John (1984). ''Dictionary of Physical Geography''. London: Penguin, 1984, p. 103. . It may also be called a gap. Particularly rugged and forbidding co ...

(or if it is large a pass). Cols are saddle-shaped depressions in the ridge between cirques. A spire-like sharp peak, the horn, forms when cirques cut back into a mountaintop from three or four sides.

Glaciers deposit rock fragments, but the most notable of the depositions are the erratics, which are large rock fragments carried some distance from the source, found on glacial terraces and ridge tops in many places throughout Denali. Headquarter erratics are made of granite and can be the size of a house. Some erratics (like those from the Yanert Valley) are located away from their original location.

Large amounts of rock debris are carried on, in, and beneath the ice as the glaciers move downslope. Lateral

Large amounts of rock debris are carried on, in, and beneath the ice as the glaciers move downslope. Lateral moraines

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris ( regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice she ...

are created as debris accumulates as low ridges of till that ride along the edge of the moving glaciers. When lateral moraines

A moraine is any accumulation of unconsolidated debris ( regolith and rock), sometimes referred to as glacial till, that occurs in both currently and formerly glaciated regions, and that has been previously carried along by a glacier or ice she ...

adjacent to each other join, they create medial moraines, which are also carried down on the surface of the moving ice.

Braided meltwater streams heavily loaded with rock debris continually shift and intertwine their channels over valley floors. Valley trains are built up as streams drop quantities of poorly sorted sediment. Valley trains are long, narrow accumulations of glacial outwash, confined by valley walls.

Kettles are formed when glacial retreat and melting is rapid, and blocks of ice are still buried under till

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

. When the ice under the till melts, the till slumps in and forms depressions called kettles. When kettles fill with water, they are known as kettle lakes

A kettle (also known as a kettle lake, kettle hole, or pothole) is a depression/hole in an outwash plain formed by retreating glaciers or draining floodwaters. The kettles are formed as a result of blocks of dead ice left behind by retreating g ...

. Kettle lakes are visible near the Polychrome Overlook, the Teklanika rest stop, and Wonder Lake.

Permafrost

Permanently frozen ground is known aspermafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

. The permafrost is discontinuous in Denali due to differences in vegetation, temperatures, snow cover, and hydrology. The active layer freezing and thawing seasonally can be from 1 inch (25 mm) to 10 feet (3.0 m) thick. The permafrost layer is located between 30 and 100 feet (9.1 and 30.5 m) below the active layer. A stand of oddly leaning white spruce growing on a lower slope of Denali is called the Drunken Forest. The trees lean due to the soil sliding as a result of permafrost freeze/thaw cycles. Permafrost impacts the ecosystem in the park by influencing hydrology, patterns of vegetation, and wildlife. During the very cold Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

climates, all of Denali was solidly frozen. The northern areas of the range are still frozen due to continued cold temperatures. About 75% of Denali had near-surface permafrost, or an active permafrost layer, in the 1950s. In the 2000s, around 50% of Denali had near-surface permafrost. It is suspected that by the 2050s, only about 6% of surface permafrost will remain. Because of climate change, most of the shallow permafrost is thawing. It is estimated that with an additional 1-2 degree warming, most of Denali's permafrost will thaw. Permafrost thaw causes landslides as the ice-rich soil transforms into mud slurry. Landslides have previously impacted accessibility in Denali by obstructing the roads in the park. Permafrost thaw releases addition carbon into the atmosphere.

Shallow ponds in Denali are known as thaw lakes and cave-in lakes formed when the water warmed by the sun forms basins in the underlying permafrost. These ponds deepen gradually during the summer and, if the temperature is high enough, they will grow in size as their rims collapse.

Thermal expansion and contraction cause permafrost cracking. In the summer water fills these cracks and forms veins called ice wedges. These wedges enlarge with seasonal freezing/thawing cycles. Some ice wedges buried for centuries are revealed during excavations or landslides.

Thermal expansion and contraction cause permafrost cracking. In the summer water fills these cracks and forms veins called ice wedges. These wedges enlarge with seasonal freezing/thawing cycles. Some ice wedges buried for centuries are revealed during excavations or landslides.

Climate

According to theKöppen climate classification

The Köppen climate classification is one of the most widely used climate classification systems. It was first published by German-Russian climatologist Wladimir Köppen (1846–1940) in 1884, with several later modifications by Köppen, nota ...

, Denali National Park has a subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of an ocean, g ...

(''Dfc''). The plant hardiness zone

A hardiness zone is a geographic area defined as having a certain average annual minimum temperature, a factor relevant to the survival of many plants. In some systems other statistics are included in the calculations. The original and most wide ...

at Denali Visitor Center is 3a with an average annual extreme minimum temperature of .

Long winters are followed by short growing seasons. Eighty percent of the bird population returns after cold months, raising their young. Most mammals and other wildlife in the park spend the brief summer months preparing for winter and raising their young.

Summers are usually cool and damp, but temperatures in the 70s are not rare. The weather is so unpredictable that there have even been instances of snow in August.

The north and south side of the Alaskan Range have completely different climates. The Gulf of Alaska carries moisture to the south side, but the mountains block water to the north side. This brings a drier climate and huge temperature fluctuations to the north. The south has transitional maritime continental climates, with moister, cooler summers, and warmer winters.

Ecology

The

The Alaska Range

The Alaska Range is a relatively narrow, 600-mile-long (950 km) mountain range in the southcentral region of the U.S. state of Alaska, from Lake Clark at its southwest endSources differ as to the exact delineation of the Alaska Range. ThBo ...

is a mountainous expanse running through the entire park, strongly influencing the park's ecosystems. Vegetation in the park depends on the altitude. The treeline

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures, extreme snowp ...

is at , causing most of the park to be a vast expanse of tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mou ...

. In the lowland areas of the park, such as the western sections surrounding Wonder Lake, spruce

A spruce is a tree of the genus ''Picea'' (), a genus of about 35 species of coniferous evergreen trees in the family Pinaceae, found in the northern temperate and boreal (taiga) regions of the Earth. ''Picea'' is the sole genus in the subfam ...

s and willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist so ...

s dominate the forest. Most trees and shrubs do not reach full size, due to unfavorable climate and thin soils. There are three types of forest in the park: from lowest to highest, they are low brush bog, bottomland spruce-poplar forest, and upland spruce-hardwood forest. The forest grows in a mosaic, due to periodic fires.

In the tundra of the park, layers of topsoil collect on rotten fragmented rock moved by thousands of years of glacial activity. Moss

Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophyta (, ) '' sensu stricto''. Bryophyta ('' sensu lato'', Schimp. 1879) may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and ...

es, fern

A fern (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta ) is a member of a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. The polypodiophytes include all living pteridophytes exce ...

s, grasses, and fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately fr ...

grow on the topsoil. In areas of muskeg

Muskeg (Ojibwe: mashkiig; cr, maskīk; french: fondrière de mousse, lit. ''moss bog'') is a peat-forming ecosystem found in several northern climates, most commonly in Arctic and boreal areas. Muskeg is approximately synonymous with bog or p ...

, tussocks form and may collect algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular micr ...

. The term 'muskeg' includes spongy waterlogged tussocks as well as deep pools of water covered by solid-looking moss. Wild blueberries

Blueberries are a widely distributed and widespread group of perennial flowering plants with blue or purple berries. They are classified in the section ''Cyanococcus'' within the genus ''Vaccinium''. ''Vaccinium'' also includes cranberries, b ...

and soap berries thrive in the tundra and provide the bears of Denali with the main part of their diet.

Over 450 species of flowering plants fill the park and can be viewed in bloom throughout summer. Images of goldenrod

Goldenrod is a common name for many species of flowering plants in the sunflower family, Asteraceae, commonly in reference to the genus '' Solidago''.

Several genera, such as '' Euthamia'', were formerly included in a broader concept of the gen ...

, fireweed

''Chamaenerion angustifolium'' is a perennial herbaceous flowering plant in the willowherb family Onagraceae. It is known in North America as fireweed, in some parts of Canada as great willowherb, in Britain and Ireland as rosebay willowherb. ...

, bluebell, and gentian filling the valleys of Denali are often used on postcards and in the artwork.

Denali is home to a variety of North American birds and mammals, including an estimated 300-350

Denali is home to a variety of North American birds and mammals, including an estimated 300-350 grizzly bear

The grizzly bear (''Ursus arctos horribilis''), also known as the North American brown bear or simply grizzly, is a population or subspecies of the brown bear inhabiting North America.

In addition to the mainland grizzly (''Ursus arctos horri ...

s on the north side of the Alaska Range (70 bears per 1,000 square miles) and an estimated 2,700 black bears (334 per 1,000 square miles). , park biologists were monitoring about 51 wolves

The wolf (''Canis lupus''; : wolves), also known as the gray wolf or grey wolf, is a large canine native to Eurasia and North America. More than thirty subspecies of ''Canis lupus'' have been recognized, and gray wolves, as popularly un ...

in 13 packs (7.4 wolves per 1,000 square miles), while surveys estimated 2,230 caribou

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

in 2013, and 1,477 moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

in 2011. Dall sheep are often seen on mountainsides. Smaller animals such as coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans'') is a species of canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the wolf, and slightly smaller than the closely related eastern wolf and red wolf. It fills much of the same ecological nich ...

s, hoary marmots, shrew

Shrews (family Soricidae) are small mole-like mammals classified in the order Eulipotyphla. True shrews are not to be confused with treeshrews, otter shrews, elephant shrews, West Indies shrews, or marsupial shrews, which belong to differ ...

s, Arctic ground squirrel

The Arctic ground squirrel (''Urocitellus parryii'') (Inuktitut: ''ᓯᒃᓯᒃ, siksik'') is a species of ground squirrel native to the Arctic and Subarctic of North America and Asia. People in Alaska, particularly around the Aleutians, refer to ...

s, beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers a ...

s, pikas, and snowshoe hare

The snowshoe hare (''Lepus americanus''), also called the varying hare or snowshoe rabbit, is a species of hare found in North America. It has the name "snowshoe" because of the large size of its hind feet. The animal's feet prevent it from sin ...

s are seen in abundance. Red and Arctic fox

The Arctic fox (''Vulpes lagopus''), also known as the white fox, polar fox, or snow fox, is a small fox native to the Arctic regions of the Northern Hemisphere and common throughout the Arctic tundra biome. It is well adapted to living in ...

species, marten

A marten is a weasel-like mammal in the genus ''Martes'' within the subfamily Guloninae, in the family Mustelidae. They have bushy tails and large paws with partially retractile claws. The fur varies from yellowish to dark brown, depending on ...

s, Canada lynx

The Canada lynx (''Lynx canadensis''), or Canadian lynx, is a medium-sized North American lynx that ranges across Alaska, Canada, and northern areas of the contiguous United States. It is characterized by its long, dense fur, triangular ears ...

, and wolverine

The wolverine (), (''Gulo gulo''; ''Gulo'' is Latin for " glutton"), also referred to as the glutton, carcajou, or quickhatch (from East Cree, ''kwiihkwahaacheew''), is the largest land-dwelling species of the family Mustelidae. It is a musc ...

s also inhabit the park but are more rarely seen due to their elusive natures.

Many migratory bird species reside in the park during late spring and summer. There are waxwing

The waxwings are three species of passerine birds classified in the genus ''Bombycilla''. They are pinkish-brown and pale grey with distinctive smooth plumage in which many body feathers are not individually visible, a black and white eyestri ...

s, Arctic warblers, pine grosbeak

The pine grosbeak (''Pinicola enucleator'') is a large member of the true finch family, Fringillidae. It is the only species in the genus ''Pinicola''. It is found in coniferous woods across Alaska, the western mountains of the United States, Can ...

s, and northern wheatears, as well as ptarmigan

''Lagopus'' is a small genus of birds in the grouse subfamily commonly known as ptarmigans (). The genus contains three living species with numerous described subspecies, all living in tundra or cold upland areas.

Taxonomy and etymology

The ge ...

and the tundra swan

The tundra swan (''Cygnus columbianus'') is a small swan of the Holarctic. The two taxa within it are usually regarded as conspecific, but are also sometimes split into two species: Bewick's swan (''Cygnus bewickii'') of the Palaearctic and th ...

. Raptors include a variety of hawk

Hawks are birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. They are widely distributed and are found on all continents except Antarctica.

* The subfamily Accipitrinae includes goshawks, sparrowhawks, sharp-shinned hawks and others. This subfa ...

s, owls, and gyrfalcon

The gyrfalcon ( or ) (), the largest of the falcon species, is a bird of prey. The abbreviation gyr is also used. It breeds on Arctic coasts and tundra, and the islands of northern North America and the Eurosiberian region. It is mainly a resid ...

s, as well as the abundant but striking golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird ...

s.

Ten species of fish, including

Ten species of fish, including trout

Trout are species of freshwater fish belonging to the genera '' Oncorhynchus'', '' Salmo'' and '' Salvelinus'', all of the subfamily Salmoninae of the family Salmonidae. The word ''trout'' is also used as part of the name of some non-salm ...

, salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus '' Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus '' Onco ...

, and Arctic grayling, share the waters of the park. Because many of the rivers and lakes of Denali are fed by glaciers, glacial silt and cold temperatures slow the metabolism of the fish, preventing them from reaching normal sizes. A single amphibious species, the wood frog

''Lithobates sylvaticus'' or ''Rana sylvatica'', commonly known as the wood frog, is a frog species that has a broad distribution over North America, extending from the boreal forest of the north to the southern Appalachians, with several nota ...

, also lives among the lakes of the park.

There are several non-native species in the park including common dandelion

''Taraxacum officinale'', the dandelion or common dandelion, is a flowering herbaceous perennial plant of the dandelion genus in the family Asteraceae (syn. Compositae). The common dandelion is well known for its yellow flower heads that turn in ...

, narrowleaf hawksbeard, white sweet clover, bird vetch, yellow toadflax, and scentless false mayweed. There are 28 invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species adv ...

documented in the park and 15 of these species are considered a threat. Volunteers and park rangers work to keep non-native plant populations low.

Denali park rangers maintain a constant effort to keep wildlife wild by limiting the interaction between humans and park animals. Feeding any animal is strictly forbidden, as it may cause adverse effects on the feeding habits of the creature. Visitors are encouraged to view animals from safe distances. In August 2012 the park experienced its first known fatal bear attack when a lone hiker apparently startled a large male grizzly while photographing it. Analysis of the scene and the hiker's camera strongly suggest he violated park regulations regarding backcountry bear encounters, which all permit holders are made aware of. Certain areas of the park are often closed due to uncommon wildlife activity, such as denning areas of wolves and bears or recent kill sites.

See also

* List of birds of Denali National Park and Preserve * List of national parks of the United StatesReferences

Bibliography

*Brown, William E. (1991A History of the Denali-Mount McKinley Region, Alaska

National Park Service *Collier, Michael (2007), ''The Geology of Denali National Park and Preserve''. Alaska Geographic. *Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (2004). ''Geology of the National Parks'', 6th ed. Kendall/Hunt. *Murie, Adolph (1961), ''A Naturalist in Alaska''. Devin-Adair. *Murie, Adolph (1981)

National Park Service *Murie, Adolph (1944)

''Fauna of the National Parks of the United States Series No. 5'', National Park Service *Norris, Frank (2006)

''Crown Jewel of the North:An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve''

Volume 1, National Park Service (10 MB download) *Norris, Frank (2006)

''Crown Jewel of the North:An Administrative History of Denali National Park and Preserve''

Volume 2, National Park Service (80 MB download) *Scoggins, Dow (2004), ''Discovering Denali: A Complete Reference Guide to Denali National Park and Mount McKinley, Alaska''. iUniverse Star. * Sheldon, Charles (1930), ''The Wilderness of Denali''. Derrydale Press (reprint), *Waits, Ike (2010), ''Denali National Park, Alaska: Guide to Hiking, Photography and Camping''. Wild Rose Guidebooks.

External links

-

National Park Service