David Wilkie (artist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

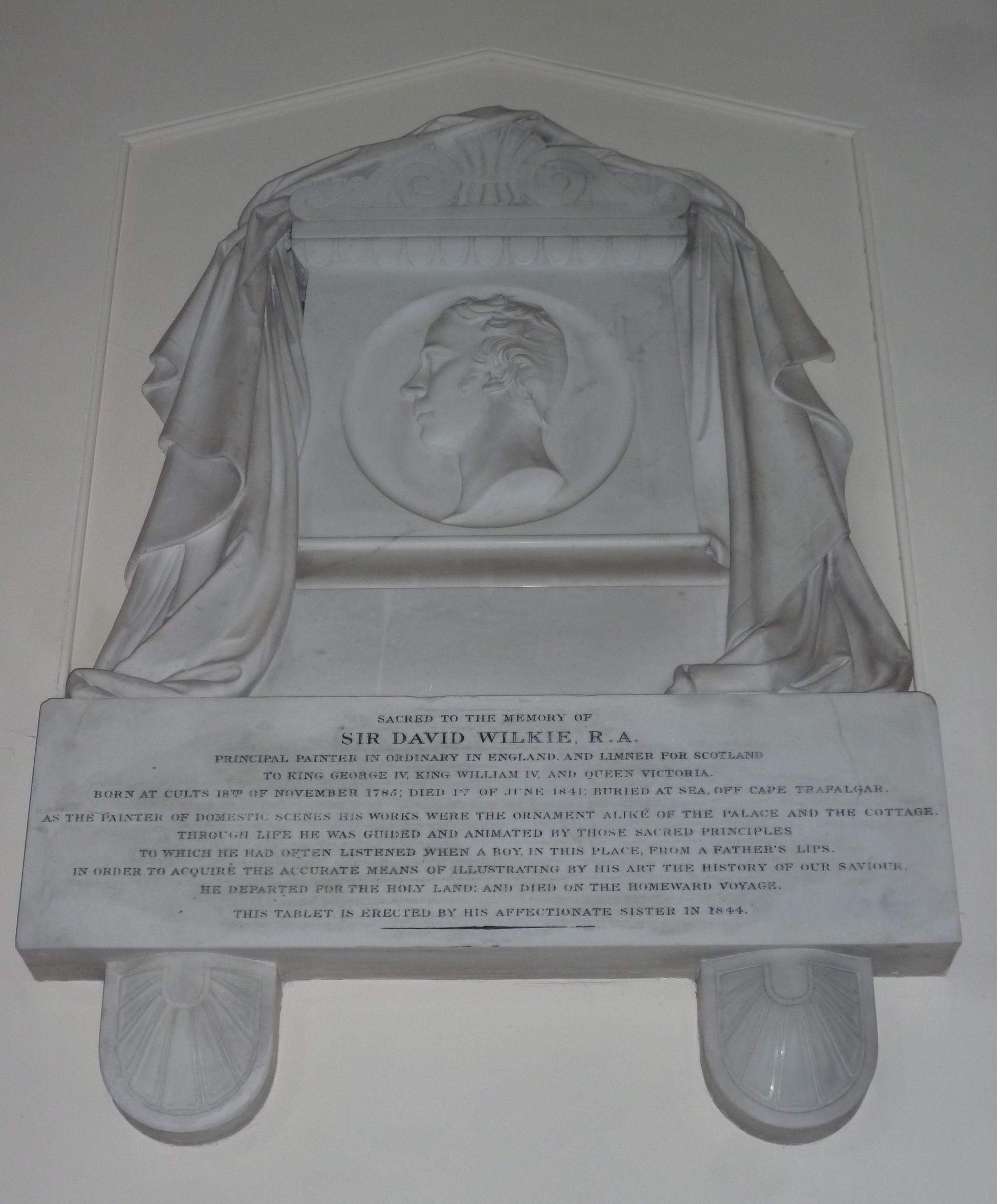

Sir David Wilkie (18 November 1785 – 1 June 1841) was a Scottish painter, especially known for his

Sir David Wilkie (18 November 1785 – 1 June 1841) was a Scottish painter, especially known for his

David Wilkie was born in Pitlessie

David Wilkie was born in Pitlessie

In 1814 he executed the ''Letter of Introduction'', one of the most delicately finished and perfect of his cabinet pictures. In the same year he made his first visit to the continent, and in Paris entered upon a profitable and delighted study of the works of art collected in the

In 1814 he executed the ''Letter of Introduction'', one of the most delicately finished and perfect of his cabinet pictures. In the same year he made his first visit to the continent, and in Paris entered upon a profitable and delighted study of the works of art collected in the

In the works which Wilkie produced in his final period he exchanged the detailed handling, the delicate finish and the reticent hues of his earlier works for a style distinguished by breadth of touch, largeness of effect, richness of tone and full force of melting and powerful colour. His subjects, too, were no longer the homely things of the genre-painter: with his broader method he attempted the portrayal of scenes from history, suggested for the most part by the associations of his foreign travel. His change of style and change of subject were severely criticized at the time; to some extent he lost his hold upon the public, who regretted the familiar subjects and the interest and pathos of his earlier productions, and were less ready to follow him into the historic scenes towards which this final phase of his art sought to lead them. The popular verdict had in it a basis of truth: Wilkie was indeed greatest as a genre-painter. But on technical grounds his change of style was criticized with undue severity. While his later works are admittedly more frequently faulty in form and draftsmanship than those of his earlier period, some of them at least (''The Bride at her Toilet'', 1838, for instance) show a true gain and development in power of handling, and in mastery over complex and forcible colour harmonies. Most of Wilkie's foreign subjects – the ''Pifferari'', ''Princess Doria'', the ''Maid of Saragossa'', the ''Spanish Podado'', a ''Guerilla Council of War'', the ''Guerilla Taking Leave of his Family'' and the ''Guerilla's Return to his Family'' – passed into the English royal collection; but the dramatic ''Two Spanish Monks of Toledo'', also entitled the ''Confessor Confessing'', became the property of the

In the works which Wilkie produced in his final period he exchanged the detailed handling, the delicate finish and the reticent hues of his earlier works for a style distinguished by breadth of touch, largeness of effect, richness of tone and full force of melting and powerful colour. His subjects, too, were no longer the homely things of the genre-painter: with his broader method he attempted the portrayal of scenes from history, suggested for the most part by the associations of his foreign travel. His change of style and change of subject were severely criticized at the time; to some extent he lost his hold upon the public, who regretted the familiar subjects and the interest and pathos of his earlier productions, and were less ready to follow him into the historic scenes towards which this final phase of his art sought to lead them. The popular verdict had in it a basis of truth: Wilkie was indeed greatest as a genre-painter. But on technical grounds his change of style was criticized with undue severity. While his later works are admittedly more frequently faulty in form and draftsmanship than those of his earlier period, some of them at least (''The Bride at her Toilet'', 1838, for instance) show a true gain and development in power of handling, and in mastery over complex and forcible colour harmonies. Most of Wilkie's foreign subjects – the ''Pifferari'', ''Princess Doria'', the ''Maid of Saragossa'', the ''Spanish Podado'', a ''Guerilla Council of War'', the ''Guerilla Taking Leave of his Family'' and the ''Guerilla's Return to his Family'' – passed into the English royal collection; but the dramatic ''Two Spanish Monks of Toledo'', also entitled the ''Confessor Confessing'', became the property of the

An elaborate ''Life of Sir David Wilkie'', by Allan Cunningham, containing the painter's journals and his observant and well-considered "Critical Remarks on Works of Art", was published in 1843. Redgrave's ''Century of Painters of the English School'' and John Burnet's ''Practical Essays on the Fine Arts'' may also be referred to for a critical estimate of his works. A list of the exceptionally numerous and excellent engravings from his pictures will be found in '' The Art Union'' for January 1840. Apart from his skill as a painter Wilkie was an admirable

An elaborate ''Life of Sir David Wilkie'', by Allan Cunningham, containing the painter's journals and his observant and well-considered "Critical Remarks on Works of Art", was published in 1843. Redgrave's ''Century of Painters of the English School'' and John Burnet's ''Practical Essays on the Fine Arts'' may also be referred to for a critical estimate of his works. A list of the exceptionally numerous and excellent engravings from his pictures will be found in '' The Art Union'' for January 1840. Apart from his skill as a painter Wilkie was an admirable

Sir David Wilkie

' (London: G. Bell and sons, 1902) * Macmillan, Duncan (1984), ''Scottish Painting: The Later Enlightenment'', in Parker, Geoff (ed.), ''

Paintings and drawings by Sir David Wilkie, R.A

' (1900).

Works in the National Galleries of Scotland

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkie, David 1785 births 1841 deaths 19th-century Scottish painters Scottish male painters Principal Painters in Ordinary 19th-century painters of historical subjects Orientalist painters People from Fife Royal Academicians Alumni of the Edinburgh College of Art Knights Bachelor People who died at sea 19th-century Scottish male artists

genre scenes

Genre art is the pictorial representation in any of various media of scenes or events from everyday life, such as markets, domestic settings, interiors, parties, inn scenes, work, and street scenes. Such representations (also called genre works, ...

. He painted successfully in a wide variety of genres, including historical scenes, portraits, including formal royal ones, and scenes from his travels to Europe and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

. His main base was in London, but he died and was buried at sea, off Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, returning from his first trip to the Middle East. He was sometimes known as the "people's painter".

He was Principal Painter in Ordinary

The title of Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King or Queen of England or, later, Great Britain, was awarded to a number of artists, nearly all mainly portraitists. It was different from the role of Serjeant Painter, and similar to the earlie ...

to King William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

and Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

. Apart from royal portraits, his best-known painting today is probably ''The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch

''The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch'', originally entitled ''Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday, June 22, 1815, Announcing the Battle of Waterloo'', is an oil painting by David Wilkie, co ...

'' of 1822 in Apsley House

Apsley House is the London townhouse of the Dukes of Wellington. It stands alone at Hyde Park Corner, on the south-east corner of Hyde Park, facing south towards the busy traffic roundabout in the centre of which stands the Wellington Arch. It i ...

.

Early life

David Wilkie was born in Pitlessie

David Wilkie was born in Pitlessie Fife

Fife (, ; gd, Fìobha, ; sco, Fife) is a council area, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland. It is situated between the Firth of Tay and the Firth of Forth, with inland boundaries with Perth and Kinross (i ...

in Scotland on 18 November 1785. He was the son of the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

minister of Cults

In modern English, ''cult'' is usually a pejorative term for a social group that is defined by its unusual religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals, or its common interest in a particular personality, object, or goal. This ...

, Fife. Caroline Wilkie was a relative. He developed a love for art at an early age. In 1799, after he had attended school at Pitlessie, Kingskettle

Kingskettle or often simply Kettle is a village and parish in Fife, Scotland. Encompassed by the Howe of Fife, the village is approximately southwest of the nearest town, Cupar, and north of Edinburgh. According to the 2011 Census for Scotlan ...

and Cupar

Cupar ( ; gd, Cùbar) is a town, former royal burgh and parish in Fife, Scotland. It lies between Dundee and Glenrothes. According to a 2011 population estimate, Cupar had a population around 9,000, making it the ninth-largest settlement in Fif ...

, his father reluctantly agreed to his becoming a painter. Through the influence of the Earl of Leven

Earl of Leven (pronounced "''Lee''-ven") is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1641 for Alexander Leslie. He was succeeded by his grandson Alexander, who was in turn followed by his daughters Margaret and Catherine (who are usu ...

Wilkie was admitted to the Trustees' Academy

Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) is one of eleven schools in the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Tracing its history back to 1760, it provides higher education in art and design, architecture, histor ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, and began the study of art under John Graham. From William Allan (afterwards Sir William Allan and president of the Royal Scottish Academy

The Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) is the country’s national academy of art. It promotes contemporary Scottish art.

The Academy was founded in 1826 by eleven artists meeting in Edinburgh. Originally named the Scottish Academy, it became the ...

) and John Burnet, the engraver of Wilkie's works, we have an interesting account of his early studies, of his indomitable perseverance and power of close application, of his habit of haunting fairs and marketplaces, and transferring to his sketchbook all that struck him as characteristic and telling in figure or incident, and of his admiration for the works of Alexander Carse

Alexander Carse (c. 1770 – February 1843) was a Scottish painter known for his scenes of Scottish life. His works include a large canvas of George IV's visit to Leith and three early paintings of football matches.

Life

Carse was born in Inne ...

and David Allan, two Scottish painters of scenes from humble life.

Among his pictures of this period might be mentioned a subject from ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'', ''Ceres

Ceres most commonly refers to:

* Ceres (dwarf planet), the largest asteroid

* Ceres (mythology), the Roman goddess of agriculture

Ceres may also refer to:

Places

Brazil

* Ceres, Goiás, Brazil

* Ceres Microregion, in north-central Goiás ...

in Search of Proserpine'', and '' Diana and Calisto'', which in 1803 gained a premium of ten guineas at the Trustees' Academy, while his pencil portraits of himself and his mother, dated that year, and now in the possession of the Duke of Buccleuch

Duke of Buccleuch (pronounced ), formerly also spelt Duke of Buccleugh, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland created twice on 20 April 1663, first for James Scott, 1st Duke of Monmouth and second suo jure for his wife Anne Scott, 4th Cou ...

, prove that Wilkie had already attained considerable certainty of touch and power of rendering character. A scene from Allan Ramsay, and a sketch from Hector Macneill

Hector Macneill (22 October 1746 – 15 March 1818) was a Scottish poet born near Roslin, Midlothian, Scotland. Macneill had been the son of a poor army captain and went to work as a clerk in 1760 at the age of fourteen. Soon, he was sent to th ...

's ballad ''Scotland's Skaith'', afterwards developed into the well-known ''Village Politicians''.

In 1804, Wilkie left the Trustees' Academy

Edinburgh College of Art (ECA) is one of eleven schools in the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Edinburgh. Tracing its history back to 1760, it provides higher education in art and design, architecture, histor ...

and returned to Cults. He established himself in the manse

A manse () is a clergy house inhabited by, or formerly inhabited by, a minister, usually used in the context of Presbyterian, Methodist, Baptist and other Christian traditions.

Ultimately derived from the Latin ''mansus'', "dwelling", from '' ...

there, and began his first important subject-picture, ''Pitlessie Fair'' (''illustration''), which includes about 140 figures, and in which he introduced portraits of his neighbours and of several members of his family circle. In addition to this elaborate figure-piece, Wilkie was much employed at the time upon portraits, both at home and in Kinghorn

Kinghorn (; gd, Ceann Gronna) is a town and parish in Fife, Scotland. A seaside resort with two beaches, Kinghorn Beach and Pettycur Bay, plus a fishing port, it stands on the north shore of the Firth of Forth, opposite Edinburgh. According ...

, St Andrews

St Andrews ( la, S. Andrea(s); sco, Saunt Aundraes; gd, Cill Rìmhinn) is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fou ...

and Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

. In the spring of 1805 he left Scotland for London, carrying with him his ''Bounty-Money, or the Village Recruit'', which he soon disposed of for £6 (£512.50 in 2021), and began to study in the schools of the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

. One of his first patrons in London was Robert Stodart, a pianoforte maker, a distant connection of the Wilkie family, who commissioned his portrait and other works and introduced the young artist to the dowager countess of Mansfield. This lady's son was the purchaser of the ''Village Politicians'', which attracted great attention when it was exhibited in the Royal Academy of 1806, where it was followed in the succeeding year by '' The Blind Fiddler'', a commission from the painter's lifelong friend Sir George Beaumont.

Historical scenes

Wilkie now turned to historical scenes, and painted his ''Alfred in the Neatherd's Cottage'', for the gallery illustrative of English history which was being formed by Alexander Davison. After its completion he returned to genre-painting, producing the ''Card-Players'' and the admirable picture of the ''Rent Day'' which was composed during recovery from a fever contracted in 1807 while on a visit to his native village. His next great work was the ''Ale-House Door'', afterwards entitled ''The Village Festival'' (now in theNational Gallery

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director o ...

), which was purchased by John Julius Angerstein

John Julius Angerstein (1735 – 22 January 1823) was a London businessman and Lloyd's underwriter, a patron of the fine arts and a collector. It was the prospect that his collection of paintings was about to be sold by his estate in 1824 ...

for 800 guineas. It was followed in 1813 by the well-known ''Blind Man's Buff'', a commission from the Prince Regent

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

, to which a companion picture, the ''Penny Wedding'', was added in 1818.

Honours

In November 1809 he was elected an associate of theRoyal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is an art institution based in Burlington House on Piccadilly in London. Founded in 1768, it has a unique position as an independent, privately funded institution led by eminent artists and architects. Its pur ...

, when he had hardly attained the age prescribed by its laws, and in February 1811 he became a full Academician. In 1812 he opened an exhibition of his collected works in Pall Mall, but the experiment was financially unsuccessful.

Travels on the Continent

In 1814 he executed the ''Letter of Introduction'', one of the most delicately finished and perfect of his cabinet pictures. In the same year he made his first visit to the continent, and in Paris entered upon a profitable and delighted study of the works of art collected in the

In 1814 he executed the ''Letter of Introduction'', one of the most delicately finished and perfect of his cabinet pictures. In the same year he made his first visit to the continent, and in Paris entered upon a profitable and delighted study of the works of art collected in the Louvre

The Louvre ( ), or the Louvre Museum ( ), is the world's most-visited museum, and an historic landmark in Paris, France. It is the home of some of the best-known works of art, including the ''Mona Lisa'' and the ''Venus de Milo''. A central l ...

. Interesting particulars of the time are preserved in his own matter-of-fact diary, and in the more sprightly and flowing pages of the journal of Benjamin Haydon

Benjamin Robert Haydon (; 26 January 178622 June 1846) was a British painter who specialised in grand historical pictures, although he also painted a few contemporary subjects and portraits. His commercial success was damaged by his often tactles ...

, his fellow traveller and brother Cedomir. On his return he began ''Distraining for Rent'', one of the most popular and dramatic of his works. In 1816 he made a tour through Netherlands and Belgium in company with Raimbach, the engraver of many of his paintings. ''Reading the Will'', a commission from the king of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, now in the New Pinakothek

The Neue Pinakothek (, ''New Pinacotheca'') is an art gallery, art museum in Munich, Germany. Its focus is Western art history, European Art of the 18th and 19th centuries, and it is one of the most important museums of art of the nineteenth cent ...

at Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the States of Germany, German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the List of cities in Germany by popu ...

, was completed in 1820; and two years later the great picture of ''The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch

''The Chelsea Pensioners reading the Waterloo Dispatch'', originally entitled ''Chelsea Pensioners Receiving the London Gazette Extraordinary of Thursday, June 22, 1815, Announcing the Battle of Waterloo'', is an oil painting by David Wilkie, co ...

'', commissioned by the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852) was an Anglo-Irish soldier and Tory statesman who was one of the leading military and political figures of 19th-century Britain, serving twice as prime minister of ...

in 1816, at a cost of 1200 guineas (£102,600 in 2021), was exhibited at the Royal Academy. On his return to Scotland in 1817, he painted ''Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels '' Ivanhoe'', '' Rob Roy' ...

and his Family'', (titled ''The Abbotsford Famil''y) a cabinet-sized picture with small full-length figures in the dress of Scottish peasants, the result of a commission by Sir Adam Ferguson

Sir Adam Ferguson (1770–1854) was deputy keeper of the regalia in Scotland.

Life

Ferguson was born on 21 December 1770, the first son of Professor Adam Ferguson.

Ferguson is recorded attending the Royal High School, Edinburgh in 1777. At both ...

, during a visit to Abbotsford.

The visit of King George IV to Scotland

In 1822 Wilkie visitedEdinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, in order to select from the Visit of King George IV to Scotland

The visit of George IV to Scotland in 1822 was the first visit of a reigning monarch to Scotland in nearly two centuries, the last being by King Charles II for his Scottish coronation in 1651. Government ministers had pressed the King to bring ...

a fitting subject for a picture. The ''Reception of the King at the Entrance of Holyrood Palace'' was the incident ultimately chosen; and in the following year, when the artist, upon the death of Raeburn Raeburn is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Agnes Raeburn (1872-1955), Scottish artist

* Anna Raeburn (born 1944), British broadcaster and journalist

* Boyd Raeburn U.S. jazz bandleader and bass saxophonist

* Henry Raeburn (17 ...

, had been appointed Royal Limner for Scotland, he received sittings from the monarch, and began to work diligently upon the subject. But several years elapsed before its completion; for, like all such ceremonial works, it proved a harassing commission, uncongenial to the painter while in progress and unsatisfactory when finished. His health suffered from the strain to which he was subjected, and his condition was aggravated by heavy domestic trials and responsibilities.

Three more years of foreign travel

In 1825 he sought relief in foreign travel: after visiting Paris, he went toItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

,ObituaryJohn Hollins

John William Hollins (born 16 July 1946) is an English retired footballer and manager. He was initially a midfielder who, later in his career, became an effective full-back. Hollins, throughout his footballing career, featured for clubs such a ...

, Gentleman's Magazine, 1855, p539, accessed May 2009 where, in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, he received the news of fresh disasters through the failure of his publishers. A residence at Toplitz and Carlsbad was tried in 1826, with little good result, and then Wilkie returned to Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, to Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

. The summer of 1827 was spent in Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

, where he had sufficiently recovered to paint his ''Princess Doria Washing the Pilgrims' Feet'', a work which, like several small pictures executed in Rome, was strongly influenced by the Italian art by which the painter had been surrounded. In October he passed into Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, whence he returned to Britain in June 1828.

It is impossible to overestimate the influence upon Wilkie's art of these three years of foreign travel. It amounts to nothing short of a complete change of style. Up to the period of his leaving Britain he had been mainly influenced by the Dutch genre-painters, whose technique he had carefully studied, whose works he frequently kept beside him in his studio for reference as he painted, and whose method he applied to the rendering of those scenes of English and Scottish life of which he was so close and faithful an observer. Teniers Teniers is a Dutch language surname. It may refer to:

*Abraham Teniers (1629–1670), Flemish painter

*David Teniers the Elder

David Teniers the Elder (158229 July 1649), Flemish painter, was born at Antwerp.

Biography

Having received his fi ...

, in particular, appears to have been his chief master; and in his earlier productions we find the sharp, precise, spirited touch, the rather subdued colouring, and the clear, silvery grey tone which distinguish this master; while in his subjects of a slightly later period – those, such as the ''Chelsea Pensioners'', the ''Highland Whisky Still'' and the ''Rabbit on the Wall'', executed in what Burnet styles his second manner, which, however, may be regarded as only the development and maturity of his first – he begins to unite to the qualities of Teniers that greater richness and fulness of effect which are characteristic of Ostade. But now he experienced the spell of the Italian masters, and of Diego Velázquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (baptized June 6, 1599August 6, 1660) was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in the court of King Philip IV of Spain and Portugal, and of the Spanish Golden Age. He was an individualistic artist of th ...

and the great Spaniards.

Later years

In the works which Wilkie produced in his final period he exchanged the detailed handling, the delicate finish and the reticent hues of his earlier works for a style distinguished by breadth of touch, largeness of effect, richness of tone and full force of melting and powerful colour. His subjects, too, were no longer the homely things of the genre-painter: with his broader method he attempted the portrayal of scenes from history, suggested for the most part by the associations of his foreign travel. His change of style and change of subject were severely criticized at the time; to some extent he lost his hold upon the public, who regretted the familiar subjects and the interest and pathos of his earlier productions, and were less ready to follow him into the historic scenes towards which this final phase of his art sought to lead them. The popular verdict had in it a basis of truth: Wilkie was indeed greatest as a genre-painter. But on technical grounds his change of style was criticized with undue severity. While his later works are admittedly more frequently faulty in form and draftsmanship than those of his earlier period, some of them at least (''The Bride at her Toilet'', 1838, for instance) show a true gain and development in power of handling, and in mastery over complex and forcible colour harmonies. Most of Wilkie's foreign subjects – the ''Pifferari'', ''Princess Doria'', the ''Maid of Saragossa'', the ''Spanish Podado'', a ''Guerilla Council of War'', the ''Guerilla Taking Leave of his Family'' and the ''Guerilla's Return to his Family'' – passed into the English royal collection; but the dramatic ''Two Spanish Monks of Toledo'', also entitled the ''Confessor Confessing'', became the property of the

In the works which Wilkie produced in his final period he exchanged the detailed handling, the delicate finish and the reticent hues of his earlier works for a style distinguished by breadth of touch, largeness of effect, richness of tone and full force of melting and powerful colour. His subjects, too, were no longer the homely things of the genre-painter: with his broader method he attempted the portrayal of scenes from history, suggested for the most part by the associations of his foreign travel. His change of style and change of subject were severely criticized at the time; to some extent he lost his hold upon the public, who regretted the familiar subjects and the interest and pathos of his earlier productions, and were less ready to follow him into the historic scenes towards which this final phase of his art sought to lead them. The popular verdict had in it a basis of truth: Wilkie was indeed greatest as a genre-painter. But on technical grounds his change of style was criticized with undue severity. While his later works are admittedly more frequently faulty in form and draftsmanship than those of his earlier period, some of them at least (''The Bride at her Toilet'', 1838, for instance) show a true gain and development in power of handling, and in mastery over complex and forcible colour harmonies. Most of Wilkie's foreign subjects – the ''Pifferari'', ''Princess Doria'', the ''Maid of Saragossa'', the ''Spanish Podado'', a ''Guerilla Council of War'', the ''Guerilla Taking Leave of his Family'' and the ''Guerilla's Return to his Family'' – passed into the English royal collection; but the dramatic ''Two Spanish Monks of Toledo'', also entitled the ''Confessor Confessing'', became the property of the Marquess of Lansdowne

Marquess of Lansdowne is a title in the Peerage of Great Britain created in 1784, and held by the head of the Petty-Fitzmaurice family. The first Marquess served as Prime Minister of Great Britain.

Origins

This branch of the Fitzmaurice famil ...

.

On his return to the UK Wilkie completed the ''Reception of the King at the Entrance of Holyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace or Holyroodhouse, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinbu ...

'' – a curious example of a union of his earlier and later styles, a "mixture" which was very justly pronounced by Haydon to be "like oil and water". His ''Preaching of John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

before the Lords of the Congregation'' had also been begun before he left for abroad; but it was painted throughout in the later style, and consequently presents a more satisfactory unity and harmony of treatment and handling. It was one of the most successful pictures of the artist's later period.

In the beginning of 1830 Wilkie was appointed to succeed Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence (13 April 1769 – 7 January 1830) was an English portrait painter and the fourth president of the Royal Academy. A child prodigy, he was born in Bristol and began drawing in Devizes, where his father was an innkeeper at t ...

as painter in ordinary to the king, and in 1836 he received the honour of knighthood

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

. The main figure-pictures which occupied him until the end were ''Columbus in the Convent at La Rabida'' (1835); ''Napoleon and Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

at Fontainebleau'' (1836); ''Empress Josephine and the Fortune-Teller'' (1837); ''Queen Victoria Presiding at her First Council'' (exhibited 1838); and ''General Sir David Baird Discovering the Body of Sultan Tippoo Sahib'' (completed 1839). His time was also much occupied with portraiture, many of his works of this class being royal commissions. His portraits are pictorial and excellent in general distribution, but the faces are frequently wanting in drawing and character. He seldom succeeded in showing his sitters at their best, and his female portraits, in particular, rarely gave satisfaction. A favourable example of his cabinet-sized portraits is that of Sir Robert Liston; his likeness of W. Esdaile is an admirable three-quarter length; and one of his finest full-lengths is the gallery portrait of Lord Kellie, in the town hall of Cupar

Cupar ( ; gd, Cùbar) is a town, former royal burgh and parish in Fife, Scotland. It lies between Dundee and Glenrothes. According to a 2011 population estimate, Cupar had a population around 9,000, making it the ninth-largest settlement in Fif ...

.

In the autumn of 1840 Wilkie resolved on a voyage to the East. Passing through the Netherlands and Germany, he reached Constantinople, where, while detained by the war in Syria, he painted a portrait of the young sultan. He then sailed for Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and travelled to Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, where he remained for some five busy weeks. The last work of all upon which he was engaged was a portrait of Muhammad Ali Pasha

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha, also known as Muhammad Ali of Egypt and the Sudan ( sq, Mehmet Ali Pasha, ar, محمد علي باشا, ; ota, محمد علی پاشا المسعود بن آغا; ; 4 March 1769 – 2 August 1849), was ...

, done at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

. On his return voyage he suffered from an attack of illness at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, and remained ill for the remainder of the journey to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, eventually dying at sea off Gibraltar, en route to Britain, on the morning of 1 June 1841. His body was consigned to the deep in the Bay of Gibraltar

The Bay of Gibraltar ( es, Bahía de Algeciras), is a bay at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula. It is around long by wide, covering an area of some , with a depth of up to in the centre of the bay. It opens to the south into the Strait ...

. Wilkie's death was commemorated by Joseph Mallord William Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner (23 April 177519 December 1851), known in his time as William Turner, was an English Romantic painter, printmaker and watercolourist. He is known for his expressive colouring, imaginative landscapes and turbule ...

in the oil painting titled ''Peace—Burial at Sea''.

Achievements

etcher

Etching is traditionally the process of using strong acid or mordant to cut into the unprotected parts of a metal surface to create a design in intaglio (incised) in the metal. In modern manufacturing, other chemicals may be used on other types ...

. The best of his plates, such as the ''Gentleman at his Desk'' (Laing, VII), the ''Pope examining a Censer'' (Laing, VIII), and the ''Seat of Hands'' (Laing, IV), are worthy to rank with the work of the greatest figure-etchers. During his lifetime he issued a portfolio of seven plates, and in 1875 David Laing catalogued and published the complete series of his etchings and dry-points, supplying the place of a few copper-plates that had been lost by reproductions, in his ''Etchings of David Wilkie and Andrew Geddes''.

Legacy

Wilkie stood as godfather to the son of his fellow Academician William Collins. The boy was named after both men, and achieved fame as the novelistWilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1859), a mystery novel and early "sensation novel", and for ''The Moons ...

.

In fiction

A painting which might be a real Wilkie or only a copy (the question is only resolved in the latter half of the book) plays a role in the novel ''Winter Solstice'' byRosamunde Pilcher

Rosamunde Pilcher, OBE (''née'' Scott; 22 September 1924 – 6 February 2019) was a British writer of romance novels, mainstream fiction, and short stories, from 1949 until her retirement in 2000. Her novels sold over 60 million copies worldw ...

.

See also

*List of Orientalist artists

This is an incomplete list of artists who have produced works on Orientalist subjects, drawn from the Islamic world or other parts of Asia. Many artists listed on this page worked in many genres, and Orientalist subjects may not have formed a m ...

* Orientalism

In art history, literature and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects in the Eastern world. These depictions are usually done by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. In particular, Orientalist p ...

Notes

References

*Further reading

* * Bayne, William, ''Sir David Wilkie, RA.,'' (Illustrated with twenty plates, etc.), London : Walter Scott Publishing Co., 1903, (Series: The makers of British art). * Gower, Ronald Sutherland.Sir David Wilkie

' (London: G. Bell and sons, 1902) * Macmillan, Duncan (1984), ''Scottish Painting: The Later Enlightenment'', in Parker, Geoff (ed.), ''

Cencrastus

''Cencrastus'' was a magazine devoted to Scottish and international literature, arts and affairs, founded after the Referendum of 1979 by students, mainly of Scottish literature at Edinburgh University, and with support from Cairns Craig, then a ...

'' No. 19, Winter 1984, pp. 25 – 27,

* Pinnington, Edward, ''Sir David Wilkie and the Scots School of Painters,'' Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier

Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier was a Scottish publishing company based in the national capital Edinburgh.

It produced many hundreds of books mainly on religious and biographical themes, especially during its heyday from about 1880 to 1910. It is ...

, 1900, ( "Famous Scots Series").

* Woodward, John (ed.). Paintings and drawings by Sir David Wilkie, R.A

' (1900).

External links

Works in the National Galleries of Scotland

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Wilkie, David 1785 births 1841 deaths 19th-century Scottish painters Scottish male painters Principal Painters in Ordinary 19th-century painters of historical subjects Orientalist painters People from Fife Royal Academicians Alumni of the Edinburgh College of Art Knights Bachelor People who died at sea 19th-century Scottish male artists