Daniel M'Naghten on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

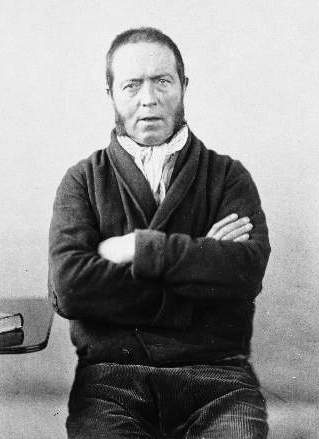

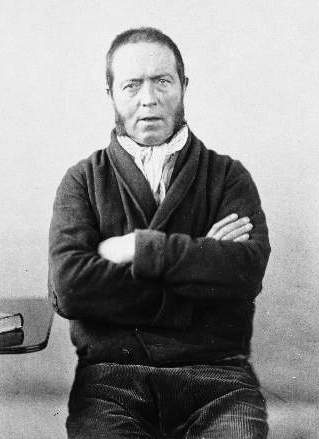

Daniel M'Naghten (sometimes spelled McNaughtan or McNaughton) (1813 – 3 May 1865) was a Scottish woodturner who assassinated English civil servant Edward Drummond while suffering from paranoid

Daniel M'Naghten (sometimes spelled McNaughtan or McNaughton) (1813 – 3 May 1865) was a Scottish woodturner who assassinated English civil servant Edward Drummond while suffering from paranoid

Daniel (1802/3–1865)''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008.

There is disagreement over how M'Naghten's name should be spelt (Mc or M' at the beginning, au or a in the middle, a, e, o or u at the end). M'Naghten is favoured in both English and American law reports, although the original trial report used M'Naughton; Bethlem and Broadmoor records use McNaughton and McNaughten.BL Diamond 1964 on the spelling of Daniel M'Naghten's name. ''Ohio State Law Journal'' 25(1). Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 86–90. In a 1981 book about the case, Richard Moran, Professor of Criminology at Mount Holyoke College, uses the spelling McNaughtan, arguing that this was the family spelling.R Moran 1981 ''Knowing Right from Wrong: the insanity defense of Daniel McNaughtan.'' The Free Press. Until 1981, there was only one known signature: that which M'Naghten affixed to a sworn statement given before the magistrate at Bow Street during his arraignment. This signature, preserved in the Metropolitan Police File at the Public Records Office in Chancery Lane, London, first came to the attention of legal scholars in 1956. According to an authority at the

There is disagreement over how M'Naghten's name should be spelt (Mc or M' at the beginning, au or a in the middle, a, e, o or u at the end). M'Naghten is favoured in both English and American law reports, although the original trial report used M'Naughton; Bethlem and Broadmoor records use McNaughton and McNaughten.BL Diamond 1964 on the spelling of Daniel M'Naghten's name. ''Ohio State Law Journal'' 25(1). Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 86–90. In a 1981 book about the case, Richard Moran, Professor of Criminology at Mount Holyoke College, uses the spelling McNaughtan, arguing that this was the family spelling.R Moran 1981 ''Knowing Right from Wrong: the insanity defense of Daniel McNaughtan.'' The Free Press. Until 1981, there was only one known signature: that which M'Naghten affixed to a sworn statement given before the magistrate at Bow Street during his arraignment. This signature, preserved in the Metropolitan Police File at the Public Records Office in Chancery Lane, London, first came to the attention of legal scholars in 1956. According to an authority at the

After his acquittal M'Naghten was transferred from Newgate Prison to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at

After his acquittal M'Naghten was transferred from Newgate Prison to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at

Transcript of the trial

(search terms: M'Naughten or t18430227-874)

{{DEFAULTSORT:M'Naghten, Daniel 1813 births 1865 deaths Scottish assassins People acquitted by reason of insanity People acquitted of murder People from Glasgow 19th-century Scottish people People detained at Broadmoor Hospital 19th-century Scottish businesspeople

Daniel M'Naghten (sometimes spelled McNaughtan or McNaughton) (1813 – 3 May 1865) was a Scottish woodturner who assassinated English civil servant Edward Drummond while suffering from paranoid

Daniel M'Naghten (sometimes spelled McNaughtan or McNaughton) (1813 – 3 May 1865) was a Scottish woodturner who assassinated English civil servant Edward Drummond while suffering from paranoid delusion

A delusion is a false fixed belief that is not amenable to change in light of conflicting evidence. As a pathology, it is distinct from a belief based on false or incomplete information, confabulation, dogma, illusion, hallucination, or som ...

s. Through his trial and its aftermath, he has given his name to the legal test of criminal insanity

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to an episodic psychiatric disease at the time of the c ...

in England and other common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

jurisdictions known as the M'Naghten rules.R MoraDaniel (1802/3–1865)''

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2008.

Life

Name and spelling

There is disagreement over how M'Naghten's name should be spelt (Mc or M' at the beginning, au or a in the middle, a, e, o or u at the end). M'Naghten is favoured in both English and American law reports, although the original trial report used M'Naughton; Bethlem and Broadmoor records use McNaughton and McNaughten.BL Diamond 1964 on the spelling of Daniel M'Naghten's name. ''Ohio State Law Journal'' 25(1). Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 86–90. In a 1981 book about the case, Richard Moran, Professor of Criminology at Mount Holyoke College, uses the spelling McNaughtan, arguing that this was the family spelling.R Moran 1981 ''Knowing Right from Wrong: the insanity defense of Daniel McNaughtan.'' The Free Press. Until 1981, there was only one known signature: that which M'Naghten affixed to a sworn statement given before the magistrate at Bow Street during his arraignment. This signature, preserved in the Metropolitan Police File at the Public Records Office in Chancery Lane, London, first came to the attention of legal scholars in 1956. According to an authority at the

There is disagreement over how M'Naghten's name should be spelt (Mc or M' at the beginning, au or a in the middle, a, e, o or u at the end). M'Naghten is favoured in both English and American law reports, although the original trial report used M'Naughton; Bethlem and Broadmoor records use McNaughton and McNaughten.BL Diamond 1964 on the spelling of Daniel M'Naghten's name. ''Ohio State Law Journal'' 25(1). Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 86–90. In a 1981 book about the case, Richard Moran, Professor of Criminology at Mount Holyoke College, uses the spelling McNaughtan, arguing that this was the family spelling.R Moran 1981 ''Knowing Right from Wrong: the insanity defense of Daniel McNaughtan.'' The Free Press. Until 1981, there was only one known signature: that which M'Naghten affixed to a sworn statement given before the magistrate at Bow Street during his arraignment. This signature, preserved in the Metropolitan Police File at the Public Records Office in Chancery Lane, London, first came to the attention of legal scholars in 1956. According to an authority at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

this signature was spelt McNaughtun. Since this spelling did not conform to any of those in popular use, it did not help to resolve the controversy.

Moran discovered a second signature during his research. On the front page of the ''Scotch Reformers Gazette'', supplementary edition for 4 March 1843, there appeared an artist's sketch of Daniel M'Naghten standing in the dock at Old Bailey, accompanied by an engraving of his signature. This signature revealed that the apparent u in the Bow Street signature was actually an a. It also indicated that the apostrophe was used by printers to signify a small letter c placed above the line, since the ''Scotch Reformers Gazette'', in the article accompanying the sketch and signature, used an inverted apostrophe to resemble more closely the letter c. The spelling "McNaughtan" was confirmed in the Glasgow Postal Directory for the years 1835 to 1844. While the Victorians were not always consistent in the way they spelled their names, even in official documents, several signatures of M'Naghten's father, uncovered while examining financial records at the Bank of Scotland, indicate that the "McNaughtan" spelling was the one used by the family.

Early life

Most of what is known about M'Naghten comes from evidence given at his trial and newspaper reports that appeared between his arrest and his trial. He was born inScotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to ...

(probably Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popu ...

) in 1813, the illegitimate son of a Glasgow woodturner and landlord, also called Daniel M'Naghten. After the death of his mother Ada, M'Naghten went to live with his father's family and became an apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

and later a journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

at his father's workshop in Stockwell Street, Glasgow. When his father decided not to offer him a partnership, M'Naghten left the business and, after a three-year career as an actor, returned to Glasgow in 1835 to set up his own woodturning workshop.

For the next five years, he ran a successful woodturning business, first in Turners Court and then in Stockwell Street. He was sober and industrious, and by living frugally was able to save a considerable sum of money. In his spare time, he attended the Glasgow Mechanics' Institute and the Athenaeum Debating Society, walked, and read. He taught himself French so that he could read La Rochefoucauld. His political views were radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

, and he employed the Chartist Abram Duncan in his workshop.

In December 1840, M'Naghten sold his business and spent the next two years in London and Glasgow, with a brief trip to France. In the summer of 1842, he attended lectures on anatomy in Glasgow, but otherwise, it is not known what he did with his time. Whilst in Glasgow in 1841, he complained to various people, including his father, the Glasgow commissioner of police, and an MP, that he was being persecuted by the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

and followed by their spies. No one took him seriously, believing him to be deluded.State Trials Report: The Queen v. Daniel McNaughton, 1843. Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 12–73.

Murder of Edward Drummond

In January 1843, M'Naghten was noticed acting suspiciously aroundWhitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Sq ...

in London. On the afternoon of 20 January, the Prime Minister's private secretary, civil servant Edward Drummond, was walking towards Downing Street

Downing Street is a street in Westminster in London that houses the official residences and offices of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Situated off Whitehall, it is long, and a few minutes' walk f ...

from Charing Cross

Charing Cross ( ) is a junction in Westminster, London, England, where six routes meet. Clockwise from north these are: the east side of Trafalgar Square leading to St Martin's Place and then Charing Cross Road; the Strand leading to the City ...

when M'Naghten approached him from behind, drew a pistol and fired at point-blank range into his back. M'Naghten was overpowered by a police constable before he could fire a second pistol. It is generally thought, although the evidence is not conclusive, that M'Naghten was under the impression that he had shot Prime Minister Robert Peel

Sir Robert Peel, 2nd Baronet, (5 February 1788 – 2 July 1850) was a British Conservative statesman who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1834–1835 and 1841–1846) simultaneously serving as Chancellor of the Excheque ...

.

At first it was thought that Drummond's wound was not serious. He managed to walk away, the bullet was removed and the first newspaper reports were optimistic: "The ball has been extracted. No vital part is injured, and urgeonsMr Guthrie and Mr Bransby Cooper have every reason to believe that Mr. Drummond is doing very well." But complications set in and possibly because of the surgeons' bleeding and leeching, Drummond died five days later.

M'Naghten appeared at the Bow Street magistrates' court the morning after the assassination attempt. He made a brief statement in which he described how persecution by the Tories had driven him to act: "The Tories in my native city have compelled me to do this. They follow, persecute me wherever I go, and have entirely destroyed my peace of mind... It can be proved by evidence. That is all I have to say." It was indeed all he had to say. He never spoke about the assassination again (apart from a dozen words when asked to plead guilty or not guilty at arraignment).

Trial

When M'Naghten was arrested, a bank receipt for £750 was found on him. His father successfully applied to the court to have the money released to finance his defence, and for the case to be adjourned for evidence relating to M'Naghten's state of mind to be gathered. A date was set for Friday 3 March. The speed and efficiency with which M'Naghten's defense was organized suggest that a number of powerful people in law and medicine were waiting for an opportunity to bring about changes in the law on criminal insanity.R Ormrod 1977 The McNaughton case and its predecessors. In DJ West and A Walk (eds) ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 4–11. M'Naghten's trial for the "willful murder of Mr. Drummond" took place at the Central Criminal Court,Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

, Thursday and Friday, 2–3 March 1843, before Chief Justice Tindal, Justice Williams and Justice Coleridge. When asked to plead guilty or not guilty, M'Naghten had said "I was driven to desperation by persecution" and, when pressed, "I am guilty of firing", which was taken as a not guilty plea. M'Naghten's defense team was led by one of London's best-known barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

s, Alexander Cockburn

Alexander Claud Cockburn ( ; 6 June 1941 – 21 July 2012) was a Scottish-born Irish-American political journalist and writer. Cockburn was brought up by British parents in Ireland, but lived and worked in the United States from 1972. Together ...

. The case was prosecuted by the solicitor-general, Sir William Follett (the attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

being busy in Lancaster prosecuting Feargus O'Connor

Feargus Edward O'Connor (18 July 1796 – 30 August 1855) was an Irish Chartist leader and advocate of the Land Plan, which sought to provide smallholdings for the labouring classes. A highly charismatic figure, O'Connor was admired for his ...

and 57 other Chartists

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, ...

following the plug riots).

Both prosecution and defense based their cases on what constituted a legal defense of insanity. Both sides agreed that M'Naghten suffered from delusions of persecution. The prosecution argued that, in spite of his "partial insanity", he was a responsible agent, capable of distinguishing right from wrong, and conscious that he was committing a crime. Witnesses, including his landlady and his anatomy lecturer, were produced to testify that he appeared generally sane. Cockburn opened his defense by acknowledging that there were difficulties in the practical application of the principle of English law that held an insane person exempt from legal responsibility and legal punishment. He went on to say that M'Naghten's delusions had led to a breakdown of moral sense and loss of self-control, which, according to medical experts, had left him in a state where he was no longer a "reasonable and responsible being". He quoted extensively from Scottish jurist Baron Hume and American psychiatrist Isaac Ray. Witnesses were produced from Glasgow to give evidence about M'Naghten's odd behavior and complaints of persecution. The defense then called medical witnesses, including Dr. Edward Monro, Sir Alexander Morison

Sir Alexander Morison M.D. (1 May 1779 – 14 March 1866) was a Scottish physician and alienist (psychiatrist).

Life

Morison was born at Anchorfield, near Edinburgh, and was educated at Edinburgh High School and the University of Edinburgh ...

and Dr Forbes Winslow, who testified that M'Naghten's delusions had deprived him of "all restraint over his actions". When the prosecution declined to produce any medical witnesses to counter this evidence, the trial was halted. Follet then made a brief, apologetic closing speech which he concluded with the words "I cannot press for a verdict against the prisoner". Chief Justice Tindal, in his summing up, stressed that the medical evidence was all on one side and reminded the jury that if they found the prisoner not guilty on the ground of insanity, proper care would be taken of him. The jury, without retiring, duly returned a verdict of not guilty on the ground of insanity.

Bethlem and Broadmoor

After his acquittal M'Naghten was transferred from Newgate Prison to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at

After his acquittal M'Naghten was transferred from Newgate Prison to the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum at Bethlem Hospital

Bethlem Royal Hospital, also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam, is a psychiatric hospital in London. Its famous history has inspired several horror books, films and TV series, most notably ''Bedlam'', a 1946 film with Bo ...

under the 1800 Act for the Safe Custody of Insane Persons charged with Offences.P Allderidge 1977 Why was McNaughton sent to Bethlem? in DJ West and A Walk (eds)''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 100–112. His admission papers describe him in the following words: "Imagines the Tories are his enemies, shy and retiring in his manner." Apart from one hunger strike, which ended with force-feeding, M'Naghten's 21 years at Bethlem appear to have been uneventful. Although no regular employment was provided for the men on the criminal wing of Bethlem, they were encouraged to keep themselves occupied with activities such as painting, drawing, knitting, board games, reading and musical instruments, and also did carpentry and decorating for the hospital.

In 1864, M'Naghten was transferred to the newly opened Broadmoor Asylum, where his admission papers describe him as: "A native of Glasgow, an intelligent man" and record how, when asked if he thinks he must have been out of his mind when he shot Edward Drummond, he answers: "Such was the Verdict – the opinion of the Jury after hearing the Evidence." During his later years at Bethlem, he had been classified as an "imbecile." He developed diabetes

Diabetes, also known as diabetes mellitus, is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by a high blood sugar level ( hyperglycemia) over a prolonged period of time. Symptoms often include frequent urination, increased thirst and increased ...

and heart problems in Bethlem; by the time he was transferred to Broadmoor, his health was declining, and he died on 3 May 1865.

Significance

The verdict in M'Naghten's trial provoked an outcry in the press and Parliament.Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, who had been the target of assassination attempts, wrote to the prime minister expressing her concern at the verdict, and the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

revived an ancient right to put questions to judges. Five questions relating to crimes committed by individuals with delusions were put to the 12 judges of the Court of Common Pleas

A court of common pleas is a common kind of court structure found in various common law jurisdictions. The form originated with the Court of Common Pleas at Westminster, which was created to permit individuals to press civil grievances against one ...

. Chief Justice Tindal delivered the answers of 11 judges ( Mr Justice Maule dissented in part) to the House of Lords on 19 June 1843. The answer to one of the questions became enshrined in law as the M'Naghten Rules and stated:

To establish a defence on the ground of insanity it must be clearly proved, that, at the time of committing the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing, or if he did know it, that he did not know that what he was doing was wrong.The House of Lords and the Judges' 'Rules' 1843 Reprinted in DJ West and A Walk (eds) 1977 ''Daniel McNaughton: his trial and the aftermath.'' Gaskell Books: 74–81.The rules dominated the law on criminal responsibility in England and Wales, the United States and many countries throughout the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

for over 100 years. In England and Wales, the defence of insanity to which the rules apply was largely superseded, in cases of murder, by the Scottish concept of diminished responsibility following the passage of the Homicide Act 1957

The Homicide Act 1957 (5 & 6 Eliz.2 c.11) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was enacted as a partial reform of the common law offence of murder in English law by abolishing the doctrine of constructive malice (except in limi ...

.

M'Naghten's defence had successfully argued that he was not legally responsible for an act that arose from a delusion; the rules represented a step backwards to the traditional 'knowing right from wrong' test of criminal insanity. Had the rules been applied in M'Naghten's own case, the verdict might have been different.

One of M'Naghten's younger half-brothers, Thomas McNaughtan, a doctor, became mayor of Blackpool

Blackpool is a seaside resort in Lancashire, England. Located on the northwest coast of England, it is the main settlement within the borough also called Blackpool. The town is by the Irish Sea, between the Ribble and Wyre rivers, and is ...

and was a magistrate.

Alternative theories

In 1843, a surgeon who was opposed to blood-letting published an anonymous pamphlet claiming that Drummond was killed not by M'Naghten's shot, but by the medical treatment he received afterwards. He said that a gunshot wound of the type sustained by Drummond was not necessarily fatal and criticised Drummond's doctors for their hasty removal of the bullet and repeated blood-lettings.An old army surgeon 1843 ''What killed Mr Drummond, the LEAD or the LANCET?'' Simpkin & Marshall. In his book ''Knowing Right From Wrong'', Richard Moran, professor of sociology atMount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a private liberal arts women's college in South Hadley, Massachusetts. It is the oldest member of the historic Seven Sisters colleges, a group of elite historically women's colleges in the Northeastern United States. ...

, argues that there are aspects of M'Naghten's case which have never been fully explained. He doubts that the money found on M'Naghten at the time of his arrest – £750 (currently worth £) – could have come entirely from his woodturning business, and points out that M'Naghten's political activity and the possibility that there may have been an element of truth to his complaints of persecution were ignored by the court. More recently, he has said that new evidence suggests that M'Naghten was a "political activist who was financed to assassinate the prime minister" and who subsequently feigned insanity.

References

Further reading

* * * *Schneider, R. D. (2009) The Lunatic and the Lords. Irwin Law, Toronto.External links

Transcript of the trial

(search terms: M'Naughten or t18430227-874)

{{DEFAULTSORT:M'Naghten, Daniel 1813 births 1865 deaths Scottish assassins People acquitted by reason of insanity People acquitted of murder People from Glasgow 19th-century Scottish people People detained at Broadmoor Hospital 19th-century Scottish businesspeople