Daniel K. Inouye on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

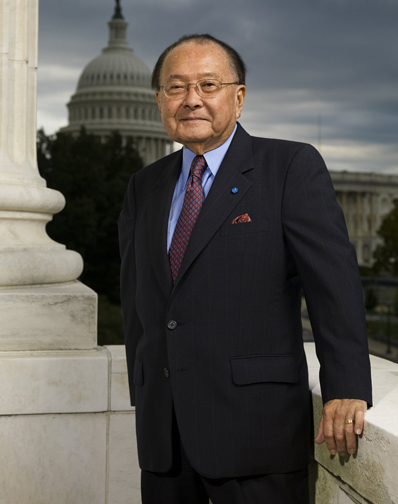

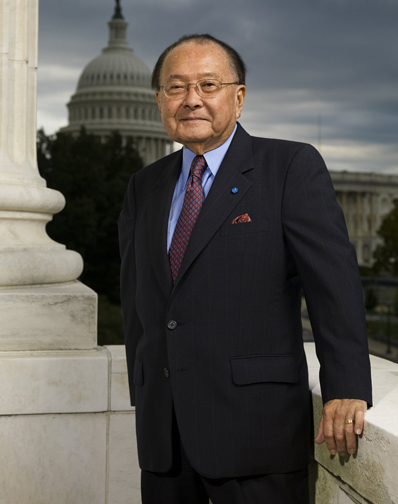

Daniel Ken Inouye ( ; September 7, 1924 – December 17, 2012) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a

In March 1943, US President

In March 1943, US President

Shortly before the Japanese surrender and end of World War II in August 1945, Inouye was shipped back to the United States to recover for eleven months at a rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers in

Shortly before the Japanese surrender and end of World War II in August 1945, Inouye was shipped back to the United States to recover for eleven months at a rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers in

Inouye decided to study law hoping it would lead him into a political career. He enrolled at the

Inouye decided to study law hoping it would lead him into a political career. He enrolled at the

In 1962, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, succeeding retiring fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

He was the chairman of the

In 1962, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, succeeding retiring fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

He was the chairman of the

In March 1982, amid controversy surrounding Democratic Senator Harrison A. Williams for taking bribes in the

In March 1982, amid controversy surrounding Democratic Senator Harrison A. Williams for taking bribes in the

Inouye's first wife was Margaret "Maggie" Shinobu Awamura, who was working as a speech instructor at the University of Hawaiʻi when Inouye was attending as a prelaw student after the war. The two married on June 12, 1948 at the Harris Memorial Methodist Church in Honolulu. She died of cancer on March 13, 2006. On May 24, 2008, he married Irene Hirano in a private ceremony in

Inouye's first wife was Margaret "Maggie" Shinobu Awamura, who was working as a speech instructor at the University of Hawaiʻi when Inouye was attending as a prelaw student after the war. The two married on June 12, 1948 at the Harris Memorial Methodist Church in Honolulu. She died of cancer on March 13, 2006. On May 24, 2008, he married Irene Hirano in a private ceremony in

* Golden Plate Award of the

* Golden Plate Award of the

On May 27, 1947, Inouye was honorably discharged and returned home as a Captain with a Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star Medal, two Purple Hearts, and 12 other medals and citations. In 2000, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

On May 27, 1947, Inouye was honorably discharged and returned home as a Captain with a Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star Medal, two Purple Hearts, and 12 other medals and citations. In 2000, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

In 2012, Inouye began using a wheelchair in the Senate to preserve his knees, and received an

In 2012, Inouye began using a wheelchair in the Senate to preserve his knees, and received an

Daniel K. Inouye Institute

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Inouye, Daniel 1924 births 2012 deaths 20th-century American politicians 21st-century American politicians American amputees American military personnel of Japanese descent American politicians of Japanese descent American politicians with disabilities American United Methodists American writers of Japanese descent Asian-American members of the United States House of Representatives Asian-American United States senators Burials in the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur Deaths from respiratory failure Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Hawaii Democratic Party United States senators from Hawaii George Washington University Law School alumni George Washington University trustees Grand Cordons of the Order of the Rising Sun Grand Crosses of the Order of Lakandula Hawaii politicians of Japanese descent Members of the Hawaii Territorial Legislature Members of the United States Congress of Japanese descent Military personnel from Hawaii Politicians from Honolulu Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients Presidents pro tempore of the United States Senate Recipients of the Four Freedoms Award Recipients of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers United States Army Medal of Honor recipients United States Army officers United States Army personnel of World War II University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa alumni Watergate scandal investigators World War II recipients of the Medal of Honor

United States senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

from Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only ...

from 1963 until his death in 2012. Beginning in 1959, he was the first U.S. representative for the State of Hawaii, and a Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor ...

recipient. A member of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

* Botswana Democratic Party

* Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*De ...

, he also served as the president pro tempore of the United States Senate

The president pro tempore of the United States Senate (often shortened to president pro tem) is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate, after the vice president. According to Article One, Section Three of the United ...

from 2010 until his death. Inouye was the highest-ranking Asian-American

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous people ...

politician in U.S. history, until Kamala Harris

Kamala Devi Harris ( ; born October 20, 1964) is an American politician and attorney who is the 49th vice president of the United States. She is the first female vice president and the highest-ranking female official in U.S. history, as well ...

became vice president in 2021. Inouye also chaired various senate committees, including those on Intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can be ...

, Indian Affairs

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), also known as Indian Affairs (IA), is a United States federal agency within the Department of the Interior. It is responsible for implementing federal laws and policies related to American Indians and Al ...

, Commerce

Commerce is the large-scale organized system of activities, functions, procedures and institutions directly and indirectly related to the exchange (buying and selling) of goods and services among two or more parties within local, regional, nation ...

, and Appropriations.

Inouye fought in World War II as part of the 442nd Infantry Regiment. He lost his right arm to a grenade wound and received several military decorations, including the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor ...

(the nation's highest military award). He later earned a J.D. degree from George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital. GW Law offers the largest range of cou ...

. Returning to Hawaii, Inouye was elected to Hawaii's territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

House of Representatives in 1953, and was elected to the territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

Senate in 1957. When Hawaii achieved statehood

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "sta ...

in 1959, Inouye was elected as its first member of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they ...

. He was first elected to the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

in 1962. He never lost an election in 58 years as an elected official, and he exercised an exceptionally large influence on Hawaii politics.

Inouye was the second Asian American

Asian Americans are Americans of Asian ancestry (including naturalized Americans who are immigrants from specific regions in Asia and descendants of such immigrants). Although this term had historically been used for all the indigenous peopl ...

senator following Hawaii Republican Hiram Fong

Hiram Leong Fong (born Yau Leong Fong; October 15, 1906 – August 18, 2004) was an American businessman, lawyer, and politician from Hawaii. Born to a sugar plantation Cantonese immigrant worker, Fong became the first Chinese-American and first ...

. Inouye was the first Japanese American

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in number to constitute the sixth largest Asi ...

to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives and the first Japanese American to serve in the U.S. Senate. Because of his seniority, Inouye became president pro tempore of the Senate following the death of Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A ...

on June 29, 2010, making him third in the presidential line of succession after the Vice President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives. At the time of his death, Inouye was the most senior sitting U.S. senator, the second-oldest sitting U.S. senator (seven and a half months younger than Frank Lautenberg

Frank Raleigh Lautenberg (; January 23, 1924 June 3, 2013) was an American businessman and Democratic Party politician who served as United States Senator from New Jersey from 1982 to 2001, and again from 2003 until his death in 2013. He was ori ...

of New Jersey), and the last sitting U.S. senator to have served during the presidencies of John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, and Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

.

Inouye was a posthumous recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

and the Order of the Paulownia Flowers. Among other public structures, Honolulu International Airport has since been renamed Daniel K. Inouye International Airport

Daniel K. Inouye International Airport , also known as Honolulu International Airport, is the main airport of Oahu, Hawaii.Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an Unincorporated area, unincorporated county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of H ...

, Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory ( Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 30, 1900, until August 21, 1959, when most of its territory, excluding ...

on September 7, 1924. His father, Hyotaro Inouye, was a jeweler who had immigrated to Hawaii from Japan as a child. His mother, Kame (''née'' Imanaga) Inouye, was a homemaker born on Maui

The island of Maui (; Hawaiian: ) is the second-largest of the islands of the state of Hawaii at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2) and is the 17th largest island in the United States. Maui is the largest of Maui County's four islands, which ...

to Japanese immigrants. Her parents died young and she was adopted and raised by a family in Honolulu. Both of Daniel's parents were Christian, and met at the River Street Methodist Church in Honolulu. They married in 1923. This heritage makes Daniel a ''Nisei

is a Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants (who are called ). The are considered the second generation ...

'' (second-generation Japanese-American) through his father and a ''Sansei

is a Japanese and North American English term used in parts of the world such as South America and North America to specify the children of children born to ethnic Japanese in a new country of residence. The ''nisei'' are considered the second g ...

'' (third-generation) through his mother. Daniel was named after Kame's adoptive father.

Inouye grew up in Bingham Tract, a Chinese-American enclave in Honolulu. He was raised Christian, and was the oldest of four children. As a child, he collected homing pigeon

The homing pigeon, also called the mail pigeon or messenger pigeon, is a variety of domestic pigeons (''Columba livia domestica'') derived from the wild rock dove, selectively bred for its ability to find its way home over extremely long dist ...

s which he hatched from eggs given to him at an army base in Schofield Barracks

Schofield Barracks is a United States Army installation and census-designated place (CDP) located in the City and County of Honolulu and in the Wahiawa District of the Hawaiian island of Oahu, Hawaii. Schofield Barracks lies adjacent to the ...

in return for him cleaning the coops. As a teenager, he worked on the local beaches teaching tourists how to surf. Inouye's parents raised him and his siblings with a mix of American and Japanese customs. His parents spoke English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

at home, but had their children attend a private Japanese language

is spoken natively by about 128 million people, primarily by Japanese people and primarily in Japan, the only country where it is the national language. Japanese belongs to the Japonic or Japanese- Ryukyuan language family. There have been ...

school in addition to public school. Inouye dropped out of the Japanese school in 1939 because he disagreed with his instructor's anti-American rhetoric, and focused on his studies at President William McKinley High School. He intended to go to college and medical school after his planned 1942 graduation.

Inouye witnessed the attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawai ...

on December 7, 1941 while still a senior in high school. The Japanese surprise attack brought the United States into World War II. Being a volunteer first aid instructor with the Red Cross

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a humanitarian movement with approximately 97 million volunteers, members and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ensure respect for all human beings, an ...

, his supervisor called on him to report to Lunalilo Elementary School which had become a Red Cross station. There, he tended to civilians injured by antiaircraft shells that had fallen into the city. After the United States declared war on Japan the next day, Inouye took up a paid job from his Red Cross supervisor to work there as a medical aide. For the remainder of his senior year, Inouye attended school during the day, and worked at the Red Cross station at night. He graduated from McKinley High School in 1942. Although Inouye wanted to join the armed forces after graduating, he did not possess that right as a Japanese-American. The United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet department originally responsible for the operation and maintenance of the United States Army, a ...

had declared all Japanese-Americans as "enemy alien

In customary international law, an enemy alien is any native, citizen, denizen or subject of any foreign nation or government with which a domestic nation or government is in conflict and who is liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and ...

s", which stipulated they could not volunteer or be drafted for military service. Inouye enrolled at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

The University of Hawaii at Mānoa (University of Hawaii—Mānoa, UH Mānoa, Hawai'i, or simply UH) is a public land-grant research university in Mānoa, a neighborhood in Honolulu, Hawaii. It is the flagship campus of the University of Haw ...

in September 1942 as a premedical student with the goal of becoming a surgeon.

Army service (1943–1947)

In March 1943, US President

In March 1943, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As th ...

established the 442nd Regimental Combat Team

The 442nd Infantry Regiment ( ja, 第442歩兵連隊) was an infantry regiment of the United States Army. The regiment is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-gene ...

, an all-''Nisei'' combat unit. Inouye applied and was initially turned down because his work at the Red Cross was deemed critical, but was inducted later that month. The unit was composed of over 2,500 ''Nisei'' from Hawaii, and 800 from the mainland. Inouye went with his unit in April to Camp Shelby

Camp Shelby is a military post whose North Gate is located at the southern boundary of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on United States Highway 49. It is the largest state-owned training site in the nation. During wartime, the camp's mission is to s ...

in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Missis ...

for a 10-month training period, postponing his medical studies. While in Mississippi, the unit visited the Rohwer War Relocation Center

The Rohwer War Relocation Center was a World War II Japanese American concentration camp located in rural southeastern Arkansas, in Desha County. It was in operation from September 18, 1942, until November 30, 1945, and held as many as 8,475 Ja ...

in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Os ...

, where Inouye witnessed the internment of Japanese Americans

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simp ...

first hand.

The 442nd shipped off to Italy in May 1944 after the conclusion of their training, shortly before the liberation of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

. Inouye was promoted to sergeant within the first three months of fighting in the Italian countryside north of Rome. The 442nd was then sent to eastern France, where they seized the towns of Bruyères

Bruyères () is a commune in the Vosges department in Grand Est in northeastern France.

The town built up around a castle built on a hill in the locality in the 6th century. It was the birthplace of Jean Lurçat, in 1892.

History

In World W ...

, Belmont, and Biffontaine from the Germans. In late October, the regiment was transferred to the Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

region of France, where they rescued 211 members of the 1st Battalion of the 141st Infantry Regiment, otherwise known as the " Lost Battalion". Inouye received a battlefield commission

A battlefield promotion (or field promotion) is an advancement in military rank that occurs while deployed in combat. A standard field promotion is advancement from current rank to the next higher rank; a "jump-step" promotion allows the recipient ...

to second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until 1 ...

for his actions there, becoming the youngest officer in his regiment. During the battle, a shot struck him in the chest directly above his heart, but the bullet was stopped by the two silver dollars he happened to have stacked in his shirt pocket. He continued to carry the coins throughout the war in his shirt pocket as good luck charms, but lost them later, shortly before the battle in which he lost his arm. The 442nd spent the next several months near Nice, guarding the French-Italian border until early 1945, when they were called to Northern Italy to assist with an assault on German strongholds in the Apennine Mountains

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

.

Arm injury

On April 21, 1945, Inouye was grievously wounded while leading an assault on the heavily defended Colle Musatello ridge near San Terenzo, Italy. The ridge served as a strongpoint of the German fortifications known as theGothic Line

The Gothic Line (german: Gotenstellung; it, Linea Gotica) was a German defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II. It formed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's last major line of defence along the summits of the northern part of ...

, the last and most unyielding line of German defensive works in Italy. During a flanking maneuver

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver is a movement of an armed force around an enemy force's side, or flank, to achieve an advantageous position over it. Flanking is useful because a force's fighting strength is typically concentrated i ...

against German machine gun nests, Inouye was shot in the stomach from 40 yards away. Ignoring his wound, he proceeded with the attack and together with the unit, destroyed the first two machine gun nests. As his squad distracted the third machine gunner, the injured Inouye crawled toward the final bunker and came within 10 yards. As he prepared to toss a grenade within, a German soldier fired out a 30 mm Schiessbecher

The Schiessbecher (alternatively: ''Schießbecher'') - literally "shooting cup" - was a German grenade launcher of World War II.

A ''Gewehrgranatgerät'' ("rifle grenade device") based on rifle grenade launcher models designed during World War ...

antipersonnel rifle grenade at Inouye, striking him in the right elbow. Although it failed to detonate, the blunt force of the grenade amputated

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on indiv ...

most of his right arm at the elbow. The nature of the injury caused his arm muscles to involuntarily squeeze the grenade tightly via a reflex arc

A reflex arc is a neural pathway that controls a reflex. In vertebrates, most sensory neurons do not pass directly into the brain, but synapse in the spinal cord. This allows for faster reflex actions to occur by activating spinal motor neurons w ...

, preventing his arm from going limp and dropping a live grenade at his feet. This left him crippled, in terrible pain, under fire with minimal cover and staring at a live grenade "clenched in a fist that suddenly didn't belong to me anymore."

Inouye's platoon moved to his aid, but he shouted for them to keep back out of fear his severed fist would involuntarily relax and drop the grenade. As the German inside the bunker began reloading his rifle with regular full metal jacket

''Full Metal Jacket'' is a 1987 war drama film directed and produced by Stanley Kubrick, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford. The film is based on Hasford's 1979 novel '' The Short-Timers'' and stars Matthe ...

ammunition to finish off Inouye, Inouye pried the live hand grenade from his useless right hand with his left, and tossed it into the bunker, killing the German. Stumbling to his feet, Inouye continued forward, killing at least one more German before suffering his fifth and final wound of the day in his left leg. Inouye fell unconscious, and awoke to see the worried men of his platoon hovering over him. His only comment before being carried away was to gruffly order them back to their positions, saying "Nobody called off the war!" By the end of the day, the ridge had fallen to American control, without the loss of any soldiers in Inouye's platoon. The remainder of Inouye's mutilated right arm was later amputated

Amputation is the removal of a limb by trauma, medical illness, or surgery. As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb, such as malignancy or gangrene. In some cases, it is carried out on indiv ...

at a field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile Ar ...

without proper anesthesia, as he had been given too much morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a pain medication, and is also commonly used recreationally, or to make other illicit opioids. There ...

at an aid station and it was feared any more would lower his blood pressure enough to kill him. The war in Europe ended on May 8, less than three weeks later.

Rehabilitation and discharge

Shortly before the Japanese surrender and end of World War II in August 1945, Inouye was shipped back to the United States to recover for eleven months at a rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers in

Shortly before the Japanese surrender and end of World War II in August 1945, Inouye was shipped back to the United States to recover for eleven months at a rehabilitation center for wounded soldiers in Atlantic City, New Jersey

Atlantic City, often known by its initials A.C., is a coastal resort city in Atlantic County, New Jersey, United States. The city is known for its casinos, boardwalk, and beaches. In 2020, the city had a population of 38,497.

. In mid-1946, Inouye was transferred to the Percy Jones Army Hospital

The English surname Percy is of Norman origin, coming from Normandy to England, United Kingdom. It was from the House of Percy, Norman lords of Northumberland, derives from the village of Percy-en-Auge in Normandy. From there, it came into us ...

in Battle Creek, Michigan

Battle Creek is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan, in northwest Calhoun County, at the confluence of the Kalamazoo and Battle Creek rivers. It is the principal city of the Battle Creek, Michigan Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), which en ...

to continue his rehabilitation for nine more months. While recovering there, Inouye met future Republican senator and presidential candidate Bob Dole

Robert Joseph Dole (July 22, 1923 – December 5, 2021) was an American politician and attorney who represented Kansas in the United States Senate from 1969 to 1996. He was the Republican Leader of the Senate during the final 11 years of his ...

, then a fellow patient. The two became friends and would often play bridge together. Dole shared with Inouye his long term plans to attend law school and become an attorney, and later run for state legislature and eventually the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washi ...

. With Inouye's plans to become a surgeon dashed due to his injury, Dole's plans for a career in public service inspired Inouye to consider entering politics. Inouye ultimately beat Dole to congress. The two remained lifelong friends. In 2003, the hospital was renamed the Hart–Dole–Inouye Federal Center in honor of the two World War II veteran

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in a military.

A military veteran that ha ...

s, as well as Democratic senator Philip Hart

Philip Aloysius Hart (December 10, 1912December 26, 1976) was an American lawyer and politician. A Democrat, he served as a United States Senator from Michigan from 1959 until his death from cancer in Washington, D.C. in 1976. He was known a ...

, who had been a patient at the hospital after sustaining injuries on D-Day.

Inouye was honorably discharged

A military discharge is given when a member of the armed forces is released from their obligation to serve. Each country's military has different types of discharge. They are generally based on whether the persons completed their training and the ...

with the rank of captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in May 1947 after 20 months of rehabilitation. At the time, he was a recipient of the Bronze Star Medal

The Bronze Star Medal (BSM) is a United States Armed Forces decoration awarded to members of the United States Armed Forces for either heroic achievement, heroic service, meritorious achievement, or meritorious service in a combat zone.

W ...

, Distinguished Service Cross, and three Purple Heart

The Purple Heart (PH) is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving, on or after 5 April 1917, with the U.S. military. With its forerunner, the Badge of Military Merit, w ...

s. Many in his regiment believed that, were he not Japanese-American, he would have been awarded the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor ...

, the nation's highest military award. Inouye eventually received the Medal of Honor on June 21, 2000 from President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, along with 19 other Japanese American servicemen in the 442nd.

Entry into politics

Inouye decided to study law hoping it would lead him into a political career. He enrolled at the

Inouye decided to study law hoping it would lead him into a political career. He enrolled at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

The University of Hawaii at Mānoa (University of Hawaii—Mānoa, UH Mānoa, Hawai'i, or simply UH) is a public land-grant research university in Mānoa, a neighborhood in Honolulu, Hawaii. It is the flagship campus of the University of Haw ...

in late 1947 as a prelaw student, majoring in government and economics. He relied on the financial benefits of the G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

to fund his education. When not in class, Inouye would volunteer for the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

* Botswana Democratic Party

* Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*De ...

at the Honolulu County Democratic Committee. He had been talked into joining the party by John A. Burns

John Anthony Burns (March 30, 1909 – April 5, 1975) was an American politician. Burns was born in Montana and became a resident of Hawaii in 1913. He served as the second governor of Hawaii from 1962 to 1974.

Early life

John Burns was ...

, a former police captain and future governor, who had ties to the Japanese American community. Though the territory of Hawaii had been politically dominated by the Republican Party, Burns convinced Inouye that the Democratic Party could help Japanese Hawaiians achieve social and economic reform. During these years, Inouye met speech instructor Margaret Awamura at the university, whom he married in 1948.

After graduating in 1950, Inouye moved with his wife to Washington D.C. so he could continue his studies at George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital. GW Law offers the largest range of cou ...

. While there, he volunteered at the Democratic National Committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is the governing body of the United States Democratic Party. The committee coordinates strategy to support Democratic Party candidates throughout the country for local, state, and national office, as well ...

(DNC) headquarters to gain more experience to bring back with him to Hawaii. Inouye earned his J.D. degree in two years, and moved back with his wife to Hawaii in late 1952. Inouye spent the next year studying for the Hawaii bar exam

A bar examination is an examination administered by the bar association of a jurisdiction that a lawyer must pass in order to be admitted to the bar of that jurisdiction.

Australia

Administering bar exams is the responsibility of the bar associ ...

and volunteering with the Democratic Party. After passing the bar exam in August 1953, Inouye was appointed assistant public prosecutor for the city and county of Honolulu by the city mayor and fellow Democrat John Wilson.

At the urging of Burns, Inouye successfully ran for the Hawaii Territorial House of Representatives in the November 1954 election, representing the Fourth District. The election came to be known as the Hawaii Democratic Revolution of 1954

The Hawaii Democratic Revolution of 1954 is a popular term for the territorial elections of 1954 in which the long dominance of the Hawaii Republican Party in the legislature came to an abrupt end, replaced by the Democratic Party of Hawaii wh ...

, as the long entrenched Republican control of the Hawaii Territorial Legislature abruptly ended with a wave of Democratic candidates taking their seats. The election also filled the legislature with Japanese American politicians, who previously held few seats. Inouye was immediately elected majority leader. He served two terms there, and was elected to the Hawaii territorial senate in 1957. Midway through Inouye's first term in the territorial senate, Hawaii achieved statehood. He won a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives as Hawaii's first full member, and took office on August 21, 1959, the same date Hawaii became a state; he was re-elected in 1960.

United States Senate (1963–2012)

In 1962, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, succeeding retiring fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

He was the chairman of the

In 1962, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, succeeding retiring fellow Democrat Oren E. Long.

He was the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee

The United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (sometimes referred to as the Intelligence Committee or SSCI) is dedicated to overseeing the United States Intelligence Community—the agencies and bureaus of the federal government of ...

between 1976 and 1979, and the chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee between 1987 and 1995. He introduced the National Museum of the American Indian Act in 1984 which led to the inauguration of the National Museum of the American Indian

The National Museum of the American Indian is a museum in the United States devoted to the culture of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. It is part of the Smithsonian Institution group of museums and research centers.

The museum has three ...

in 2004. He was chairman of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee between 2001 and 2003, chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation is a standing committee of the United States Senate. Besides having broad jurisdiction over all matters concerning interstate commerce, science and technology policy, a ...

between 2007 and 2009 and chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Appropriations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It has jurisdiction over all discretionary spending legislation in the Senate.

The Senate Appropriations Committee is the largest committe ...

between 2009 and 2012.

He was reelected eight times, usually without serious difficulty. His closest race was in 1992

File:1992 Events Collage V1.png, From left, clockwise: 1992 Los Angeles riots, Riots break out across Los Angeles, California after the Police brutality, police beating of Rodney King; El Al Flight 1862 crashes into a residential apartment buildi ...

, when state senator Rick Reed held him to 57 percent of the vote; this was the only time he received less than 69 percent of the vote. He delivered the keynote address at the turbulent 1968 Democratic National Convention

The 1968 Democratic National Convention was held August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Earlier that year incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson had announced he would not seek reelection, thus mak ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

Associated Press (Chicago), "Keynoter Knows Sting of Bias, Poverty", ''St. Petersburg Times'', August 27, 1968. and gained national attention for his service on the Senate Watergate Committee

The Senate Watergate Committee, known officially as the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, was a special committee established by the United States Senate, , in 1973, to investigate the Watergate scandal, with the power to i ...

.

Inouye was also involved in the Iran-Contra investigations of the 1980s, chairing a special committee ( Senate Select Committee on Secret Military Assistance to Iran and the Nicaraguan Opposition) from 1987 until 1989. During the hearings, Inouye referred to the operations that had been revealed as a "secret government", saying:

Criticizing the logic of Marine Lt. Colonel Oliver North

Oliver Laurence North (born October 7, 1943) is an American political commentator, television host, military historian, author, and retired United States Marine Corps lieutenant colonel.

A veteran of the Vietnam War, North was a National Secu ...

's justifications for his actions in the affair, Inouye made reference to the Nuremberg trials, provoking a heated interruption from North's attorney Brendan Sullivan, an exchange that was widely repeated in the media at the time. He was also seen as a pro-Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a Country, country in East Asia, at the junction of the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the China, People's Republic of China (PRC) to the n ...

senator and helped in forming the Taiwan Relations Act

The Taiwan Relations Act (TRA; ; Pha̍k-fa-sṳ: ''Thôi-van Kwan-hè-fap''; ) is an act of the United States Congress. Since the formal recognition of the People's Republic of China, the Act has defined the officially substantial but non-dipl ...

.

On May 1, 1977, Inouye stated that President Carter had telephoned him to express his objections to a sentence in the Senate Intelligence Committee's report on the Central Intelligence Agency.

On November 20, 1993, Inouye voted against the North American Free Trade Agreement

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA ; es, Tratado de Libre Comercio de América del Norte, TLCAN; french: Accord de libre-échange nord-américain, ALÉNA) was an agreement signed by Canada, Mexico, and the United States that crea ...

. The trade agreement linked the United States, Canada, and Mexico into a single free trade zone and was signed into law on December 8 by President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

.

In 2009, Inouye assumed leadership of the powerful Senate Committee on Appropriations after longtime chairman Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A ...

stepped down. Following the latter's death on June 28, 2010, Inouye was elected President pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase ''pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being".

...

, the officer third in the presidential line of succession.

In 2010, Inouye announced his decision to run for a ninth term. He easily won the Democratic primary—the real contest in this heavily Democratic state—and then trounced Republican state representative Campbell Cavasso with 74 percent of the vote.

Inouye ran for Senate Majority Leader

The positions of majority leader and minority leader are held by two United States senators and members of the party leadership of the United States Senate. They serve as the chief spokespersons for their respective political parties holding ...

several times without success.

Prior to his death, Inouye announced that he planned to run for a record tenth term in 2016 when he would have been 92 years old. He also said,

1980s

In 1986, West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd opted to run for Senate Majority Leader, believing that his two opponents to claiming the position would be Inouye and Louisiana SenatorJ. Bennett Johnston

John Bennett Johnston Jr. (born June 10, 1932) is a retired American attorney, politician, and later lobbyist. A member of the Democratic Party, Johnston represented Louisiana in the U.S. Senate from 1972 to 1997.

Beginning his political caree ...

. Cutting a deal with Inouye, Byrd pledged that he would step aside from the position in 1989 if Inouye would support him for Senate Majority Leader of the 100th United States Congress

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1. I ...

. Inouye accepted the offer and was given the chance to select the new Senate sergeant-at-arms.

Foreign policy

In early 1981, Inouye called for tighter restrictions on what Americans can ship overseas, citing his belief that American international stature would be harmed along with the country's foreign policy interests in the event of the shipments causing environmental damage. In March 1981, Inouye was one of 24 elected officials to issue a joint statement calling on the Reagan administration to compose a method of finding a peaceful solution that would end The Troubles inNorthern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label=Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is #Descriptions, variously described as ...

.

In July 1981, a Federal commission began hearings to decide on rewarding compensations to Japanese-Americans placed in internment camps during World War II, Inouye and fellow Hawaii Senator Spark M. Matsunaga delivering opening statements. In November, during an appearance at the opening of a 10-day public forum at Tufts University on Japanese internment, Inouye stated his opposition to distributing reparation fees for Japanese-Americans previously incarcerated during World War II, adding that it "would be insulting even to try to do so." In August 1988, Inouye attended President Reagan's signing of legislation apologizing for the internment camps and establishing a $1.25 billion trust fund to pay reparations to both those who were placed in camps and to their families. In September 1989, during the Senate's debate over bestowing reparations to Japanese-Americans interned during World War II, Inouye delivered his first public speech on the issue and noted $22,000 were bestowed to each captive American in the Iran hostage crisis

On November 4, 1979, 52 United States diplomats and citizens were held hostage after a group of militarized Iranian college students belonging to the Muslim Student Followers of the Imam's Line, who supported the Iranian Revolution, took over ...

.

In October 2002, Inouye was one of 23 senators who voted against authorization of the use of military force in Iraq.

Domestic policy

In March 1982, amid controversy surrounding Democratic Senator Harrison A. Williams for taking bribes in the

In March 1982, amid controversy surrounding Democratic Senator Harrison A. Williams for taking bribes in the Abscam

Abscam (sometimes written ABSCAM) was an FBI sting operation in the late 1970s and early 1980s that led to the convictions of seven members of the United States Congress, among others, for bribery and corruption. The two-year investigation init ...

sting operation, Inouye delivered a closing defense argument stating the possibility of the Senate looking foolish in the event the conviction was reversed on appeal. Inouye confirmed that he had received telephone calls regarding Williams critiquing his remarks during his defense of himself the previous week and questioned if the Senate was going to punish him "because his presentation was rambling, not in the tradition of Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

" and for his wife believing in him.

In October 1982, after President Reagan appointed two new members to the board of the Legal Services Corporation, Inouye was one of 32 Senators to sign a letter expressing grave concerns over the appointments.

On December 23, Inouye voted against a 5 cent a gallon increase in gasoline taxes across the US imposed to aid the financing of highway repairs and mass transit. The bill passed on the last day of the 97th United States Congress

The 97th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from January 3, 1981 ...

.

In March 1984, Inouye voted against a constitutional amendment authorizing periods in public school for silent prayer and against President Reagan's unsuccessful proposal for a constitutional amendment permitting organized school prayer in public schools. In August, Inouye secured the acceptance of the Senate's defense appropriations subcommittee for an amendment meant to cure mainland milk arriving at Hawaiian and Alaskan military bases sour, arguing thousands of gallons of milk coming from the mainland must be dumped due to their souring and said shipments were arriving eight days after pasteurization.

In February 1989, after Oliver North went on trial in Federal District Court amid accusations of a dozen crimes in accordance with his role in diverting profits from the secret sale of arms to Iran to the Nicaraguan rebels and Jack Brooks questioned North's role in composing a "contingency plan in the event of an emergency that would suspend the American Constitution," Inouye replied that the inquiry touched on both a classified and sensitive matter that would only be discussed in a closed session.

Gang of 14

On May 23, 2005, Inouye was a member of a bipartisan group of 14 moderate senators, known as the Gang of 14, to forge a compromise on the Democrats' use of the judicialfilibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

, thus blocking the Republican leadership's attempt to implement the "nuclear option

In the United States Senate, the nuclear option is a parliamentary procedure that allows the Senate to override a standing rule by a simple majority, avoiding the two-thirds supermajority normally required to invoke cloture on a resolution to ...

," a means of forcibly ending a filibuster. Under the agreement, the Democrats would retain the power to filibuster a Bush judicial nominee only in an "extraordinary circumstance," and the three most conservative Bush appellate court

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of ...

nominees (Janice Rogers Brown

Janice Rogers Brown (born May 11, 1949) is an American jurist. She served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit from 2005 to 2017 and before that, Associate Justice of the Cal ...

, Priscilla Owen

Priscilla Richman (formerly Priscilla Richman Owen) (born October 4, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as the chief United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. She was previously a justice ...

, and William H. Pryor, Jr.) would receive a vote by the full U.S. Senate.

Electoral history

Inouye never lost an election. In August 1968, PresidentLyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

placed a phone call to vice president and Democratic presumptive presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey

Hubert Horatio Humphrey Jr. (May 27, 1911 – January 13, 1978) was an American pharmacist and politician who served as the 38th vice president of the United States from 1965 to 1969. He twice served in the United States Senate, representing M ...

, urging him to select Inouye as his running mate. Johnson went as far as to request a background check on Inouye from the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

. Johnson told Humphrey that Inouye's World War II injuries would silence Humphrey's critics on the Vietnam War: "He answers Vietnam with that empty sleeve. He answers your problems with (Republican presumptive presidential nominee and former vice president Richard) Nixon with that empty sleeve", Johnson said. Humphrey eventually chose Edmund Muskie

Edmund Sixtus Muskie (March 28, 1914March 26, 1996) was an American statesman and political leader who served as the 58th United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter, a List of United States Senators from Maine, United States S ...

as his running mate, and lost the election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has oper ...

. According to his chief of staff, Jennifer Sabas, Inouye knew that he was being considered as a vice presidential pick, but was uninterested in the possibility, apparently content with his current position.

Family

Inouye's first wife was Margaret "Maggie" Shinobu Awamura, who was working as a speech instructor at the University of Hawaiʻi when Inouye was attending as a prelaw student after the war. The two married on June 12, 1948 at the Harris Memorial Methodist Church in Honolulu. She died of cancer on March 13, 2006. On May 24, 2008, he married Irene Hirano in a private ceremony in

Inouye's first wife was Margaret "Maggie" Shinobu Awamura, who was working as a speech instructor at the University of Hawaiʻi when Inouye was attending as a prelaw student after the war. The two married on June 12, 1948 at the Harris Memorial Methodist Church in Honolulu. She died of cancer on March 13, 2006. On May 24, 2008, he married Irene Hirano in a private ceremony in Beverly Hills, California

Beverly Hills is a city located in Los Angeles County, California. A notable and historic suburb of Greater Los Angeles, it is in a wealthy area immediately southwest of the Hollywood Hills, approximately northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Be ...

. Hirano was president and founding chief executive officer of the Japanese American National Museum

The is located in Los Angeles, California, and dedicated to preserving the history and culture of Japanese Americans. Founded in 1992, it is located in the Little Tokyo area near downtown. The museum is an affiliate within the Smithsonian Aff ...

in Los Angeles, California. She resigned the position at the time of her marriage, in order to be closer to her husband. According to the ''Honolulu Advertiser

''The Honolulu Advertiser'' was a daily newspaper published in Honolulu, Hawaii. At the time publication ceased on June 6, 2010, it was the largest daily newspaper in the American state of Hawaii. It published daily with special Sunday and Int ...

'', Inouye was 24 years older than Hirano. On May 27, 2010, Hirano was elected chair of the nation's second largest non-profit organization, The Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the death ...

. Hirano outlived him by more than seven years; she died on April 7, 2020.

Inouye's son Kenny was the guitarist for the hardcore punk

Hardcore punk (also known as simply hardcore) is a punk rock music genre and subculture that originated in the late 1970s. It is generally faster, harder, and more aggressive than other forms of punk rock. Its roots can be traced to earlier pu ...

band Marginal Man.

Honors

* Golden Plate Award of the

* Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet o ...

in 1968.

* Grand Cross of the Philippine Legion of Honor in 1993.

* On June 21, 2000, Inouye was presented the Medal of Honor

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is the United States Armed Forces' highest military decoration and is awarded to recognize American soldiers, sailors, marines, airmen, guardians and coast guardsmen who have distinguished themselves by acts of valor ...

by President Bill Clinton for his service during World War II.

* Also in 2000, Inouye was awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese government, created on 10 April 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight f ...

by the Emperor of Japan

The Emperor of Japan is the monarch and the head of the Imperial Family of Japan. Under the Constitution of Japan, he is defined as the symbol of the Japanese state and the unity of the Japanese people, and his position is derived from "the wi ...

in recognition of his long and distinguished career in public service.

* In 2006, the U.S. Navy Memorial awarded Inouye its Naval Heritage award for his support of the U.S. Navy and the military during his terms in the Senate.

* Grand Cross (''Bayani'') of the Order of Lakandula on August 14, 2006.

* In 2007, Inouye was personally inducted as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

by President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

Nicolas Sarkozy

Nicolas Paul Stéphane Sarközy de Nagy-Bocsa (; ; born 28 January 1955) is a French politician who served as President of France from 2007 to 2012.

Born in Paris, he is of Hungarian, Greek Jewish, and French origin. Mayor of Neuilly-sur-Sei ...

.

* In February 2009, a bill was introduced in the Philippine House of Representatives by Rep. Antonio Diaz seeking to confer honorary Filipino citizenship on Inouye, Senators Ted Stevens

Theodore Fulton Stevens Sr. (November 18, 1923 – August 9, 2010) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a U.S. Senator from Alaska from 1968 to 2009. He was the longest-serving Republican Senator in history at the time he left ...

and Daniel Akaka

Daniel Kahikina Akaka (; September 11, 1924 – April 6, 2018) was an American educator and politician who served as a United States Senator from Hawaii from 1990 to 2013. A member of the Democratic Party, Akaka was the first U.S. Senator of Nati ...

, and Representative Bob Filner

Robert Earl "Bob" Filner (born September 4, 1942) is an American former politician who was the 35th mayor of San Diego from December 2012 through August 2013, when he resigned amid multiple allegations of sexual harassment. He later pleaded gui ...

for their role in securing the passage of benefits for Filipino World War II veterans.

* In June 2011, Inouye was appointed a Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers, the highest Japanese honor which may be conferred upon a foreigner who is not a head of state. Only the seventh American to be so honored, he is also the first American of Japanese descent to receive it. The conferment of the order was "to recognize his continued significant and unprecedented contributions to the enhancement of goodwill and understanding between Japan and the United States."

* In 2011, Philippine president Benigno Aquino III

Benigno Simeon Cojuangco Aquino III (; February 8, 1960 – June 24, 2021), also known as Noynoy Aquino and Colloquialism, colloquially as PNoy, was a Filipino politician who served as the List of presidents of the Philippines, 15th presid ...

conferred Order of Sikatuna upon Inouye. He had previously been awarded Order of Lakandula

The Order of Lakandula ( fil, Orden ni Lakandula) is one of the highest civilian orders of the Philippines, established on September 19, 2003. It is awarded for political and civic merit and in memory of King Lakandula’s dedication to the res ...

and a Philippine Republic Presidential Unit Citation

The Philippine Presidential Unit citation BadgeThe AFP Adjutant General, ''Awards and Decorations Handbook'', 1997, OTAG, p. 65. is a unit decoration of the Republic of the Philippines. It has been awarded to certain units of the United States m ...

.

* Inouye was inducted as an honorary member of the Navajo Nation

The Navajo Nation ( nv, Naabeehó Bináhásdzo), also known as Navajoland, is a Native Americans in the United States, Native American Indian reservation, reservation in the United States. It occupies portions of northeastern Arizona, northwe ...

and titled "The Leader Who Has Returned With a Plan."

* On August 8, 2013, Inouye was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merito ...

by President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

. The citation in the press release reads as follows:

::Daniel Inouye was a lifelong public servant. As a young man, he fought in World War II with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, for which he received the Medal of Honor. He was later elected to the Hawaii Territorial House of Representatives, the United States House of Representatives, and the United States Senate. Senator Inouye was the first Japanese American to serve in Congress, representing the people of Hawaii from the moment they joined the Union.

* In August 2021, while visiting Japan for the Tokyo Olympics, First Lady

First lady is an unofficial title usually used for the wife, and occasionally used for the daughter or other female relative, of a non- monarchical head of state or chief executive. The term is also used to describe a woman seen to be at the ...

Jill Biden

Jill Tracy Jacobs Biden (born June 3, 1951) is an American educator and the current first lady of the United States since 2021, as the wife of President Joe Biden. She was the second lady of the United States from 2009 to 2017 when her husb ...

dedicated a room in the U.S. ambassador's residence to Inouye and his wife, Irene.

Awards and decorations

On May 27, 1947, Inouye was honorably discharged and returned home as a Captain with a Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star Medal, two Purple Hearts, and 12 other medals and citations. In 2000, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

On May 27, 1947, Inouye was honorably discharged and returned home as a Captain with a Distinguished Service Cross, Bronze Star Medal, two Purple Hearts, and 12 other medals and citations. In 2000, his Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

Death

In 2012, Inouye began using a wheelchair in the Senate to preserve his knees, and received an

In 2012, Inouye began using a wheelchair in the Senate to preserve his knees, and received an oxygen concentrator

An oxygen concentrator is a device that concentrates the oxygen from a gas supply (typically ambient air) by selectively removing nitrogen to supply an oxygen-enriched product gas stream. They are used industrially and as medical devices for ox ...

to aid his breathing. In November 2012, he suffered a minor cut after falling in his apartment and was treated at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

The Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), formerly known as the National Naval Medical Center and colloquially referred to as the Bethesda Naval Hospital, Walter Reed, or Navy Med, is a United States' tri-service military med ...

. On December 6, he was again hospitalized at George Washington University Hospital

The George Washington University Hospital is a for-profit hospital, located in Washington, D.C. in the United States. It is affiliated with the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. The current facility opened o ...

so doctors could further regulate his oxygen intake, and was transferred to Walter Reed Medical Center on December 10. He died there of respiratory complications seven days later on December 17, 2012. According to the senator's Congressional website, his last word was "Aloha

''Aloha'' ( , ) is the Hawaiian word for love, affection, peace, compassion and mercy, that is commonly used as a simple greeting but has a deeper cultural and spiritual significance to native Hawaiians, for whom the term is used to define a f ...

." Prior to his death, Inouye left a letter encouraging Governor Neil Abercrombie

Neil Abercrombie (born June 26, 1938) is an American politician who served as the seventh governor of Hawaii from 2010 to 2014. He is a member of the Democratic Party.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Abercrombie is a graduate of Union College and th ...

to appoint Colleen Hanabusa

Colleen Wakako Hanabusa ( ja, 花房 若子; born May 4, 1951) is an American lawyer and politician who served as the U.S. representative for from 2011 to 2015 and again from 2016 to 2019. A member of the Democratic Party, she ran for her party's ...

to succeed Inouye should he become incapacitated; instead Abercrombie appointed Hawaii's Lieutenant Governor Brian Schatz

Brian Emanuel Schatz (; born October 20, 1972) is an American educator and politician serving as the senior United States senator from Hawaii, a seat he has held since 2012. A member of the Democratic Party, Schatz served in the Hawaii House o ...

.

Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid

Harry Mason Reid Jr. (; December 2, 1939 – December 28, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Nevada from 1987 to 2017. He led the Senate Democratic Caucus from 2005 to 2017 and was the Senat ...

announced Inouye's death on the floor of the Senate, referring to Inouye as "certainly one of the giants of the Senate." Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell

Addison Mitchell McConnell III (born February 20, 1942) is an American politician and retired attorney serving as the senior United States senator from Kentucky and the Senate minority leader since 2021. Currently in his seventh term, McConne ...

referred to Inouye as one of the finest Senators in United States history. President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, Obama was the first Af ...

referred to him as a "true American hero".

Inouye's body lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda

The United States Capitol rotunda is the tall central rotunda of the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. It has been described as the Capitol's "symbolic and physical heart". Built between 1818 and 1824, the rotunda is located below the ...

on December 20, 2012. President Obama, former President Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and again ...

, Vice President Joe Biden, House Speaker John Boehner

John Andrew Boehner ( ; born , 1949) is an American retired politician who served as the 53rd speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 2011 to 2015. A member of the Republican Party, he served 13 terms as the U.S. repres ...

and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid spoke at a funeral service at the Washington National Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington, commonly known as Washington National Cathedral, is an American cathedral of the Episcopal Church. The cathedral is located in Washington, D.C., the ca ...

on December 21. Inouye's body was then flown to Hawaii where it lay in state at the Hawaii State Capitol

The Hawaii State Capitol is the official statehouse or capitol building of the U.S. state of Hawaii. From its chambers, the executive and legislative branches perform the duties involved in governing the state. The Hawaii State Legislature—com ...

on December 22. A second funeral service was held at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific

The National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific (informally known as Punchbowl Cemetery) is a United States national cemetery, national cemetery located at Punchbowl Crater in Honolulu, Hawaii. It serves as a memorial to honor those men and wo ...

in Honolulu the following day.

Legacy

The Daniel K. Inouye Graduate School of Nursing, founded in 1993, is part of theUniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU) is a health science university of the U.S. federal government. The primary mission of the school is to prepare graduates for service to the U.S. at home and abroad in the medical corps a ...

.

He made a cameo appearance as himself in the 1994 film ''The Next Karate Kid

''The Next Karate Kid'' is a 1994 American martial arts drama film, and the fourth installment in ''The Karate Kid'' franchise, following ''The Karate Kid Part III'' (1989). It stars Hilary Swank as Julie Pierce (in her first theatrical appeara ...

'', giving the opening speech at Arlington National Cemetery

Arlington National Cemetery is one of two national cemeteries run by the United States Army. Nearly 400,000 people are buried in its 639 acres (259 ha) in Arlington, Virginia. There are about 30 funerals conducted on weekdays and 7 held on Sa ...

for a commendation for Japanese-Americans who fought in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team

The 442nd Infantry Regiment ( ja, 第442歩兵連隊) was an infantry regiment of the United States Army. The regiment is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-gene ...

during World War II.

In 2007, The Citadel

The Citadel, The Military College of South Carolina, commonly known simply as The Citadel, is a public senior military college in Charleston, South Carolina. Established in 1842, it is one of six senior military colleges in the United States. ...

dedicated Inouye Hall at the Citadel/South Carolina Army National Guard Marksmanship Center to Senator Inouye, who helped make the Center possible.

In May 2013, Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus announced that the next would be named . The destroyer was officially christened at Bath Iron Works on June 22, 2019.

In December 2013, the Advanced Technology Solar Telescope at Haleakala Observatory on Maui

The island of Maui (; Hawaiian: ) is the second-largest of the islands of the state of Hawaii at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2) and is the 17th largest island in the United States. Maui is the largest of Maui County's four islands, which ...

was renamed the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope.

Numerous federal properties at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam and around Hawai'i have been dedicated to Senator Inouye, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (abbreviated as NOAA ) is an United States scientific and regulatory agency within the United States Department of Commerce that forecasts weather, monitors oceanic and atmospheric conditi ...

''Daniel K. Inouye Regional Center'' (2013), the Hawaii Air National Guard ''Daniel K. Inouye Fighter Squadron Operations & Aircraft Maintenance Facility'' (2014), the ''Senator Daniel K. Inouye'' Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) is an agency within the U.S. Department of Defense whose mission is to recover American military personnel listed as prisoners of war (POW) or missing in action (MIA) from designated past conflicts, ...

building (2015), the ''Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies The Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies (DKI APCSS) is a U.S. Department of Defense institute that officially opened Sept. 4, 1995, in Honolulu, Hawaii. The Center addresses regional and global security issues, inviting militar ...

'' at Fort Derussy (2015), and the Pacific Missile Range Facility

The Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands is a U.S. naval facility and airport located five nautical miles (9 km) northwest of the central business district of Kekaha, in Kauai County, Hawaii, United States.

PMRF is the world's ...

''Daniel K. Inouye Range and Operations Center'' on Kauai (2016).

In 2014, Israel named the simulator room of the Arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers ca ...

anti-missile defense system in his honor, the first time that a military facility has been named after a foreign national.

A Boeing C-17 Globemaster III

The McDonnell Douglas/Boeing C-17 Globemaster III is a large military transport aircraft that was developed for the United States Air Force (USAF) from the 1980s to the early 1990s by McDonnell Douglas. The C-17 carries forward the name of two ...

, tail number 5147, of the 535th Airlift Squadron

The 535th Airlift Squadron is part of the 15th Wing at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, Hawaii. It operates C-17 Globemaster III aircraft providing airlift in the Pacific theater.

The squadron was first established during World War II as the ...

, was dedicated ''Spirit of Daniel Inouye'' on August 20, 2014.

The Parade Field at Fort Benning