Daniel Defoe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist,

Defoe's first notable publication was '' An Essay Upon Projects'', a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a

Defoe's first notable publication was '' An Essay Upon Projects'', a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a

In despair during his imprisonment for the seditious libel case, Defoe wrote to William Paterson, the London Scot and founder of the

In despair during his imprisonment for the seditious libel case, Defoe wrote to William Paterson, the London Scot and founder of the

Defoe's description of

Defoe's description of

From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including ''Religious Courtship'' (1722), ''The Complete English Tradesman'' (1726) and ''The New Family Instructor'' (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as ''The Great Law of Subordination Considered'' (1724) and ''Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business'' (1725) and works on the supernatural, like '' The Political History of the Devil'' (1726), ''A System of Magick'' (1727) and ''An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions'' (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include ''A General History of Discoveries and Improvements'' (1727) and ''Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis'' (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement, apart from the novels, is the magisterial ''

From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including ''Religious Courtship'' (1722), ''The Complete English Tradesman'' (1726) and ''The New Family Instructor'' (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as ''The Great Law of Subordination Considered'' (1724) and ''Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business'' (1725) and works on the supernatural, like '' The Political History of the Devil'' (1726), ''A System of Magick'' (1727) and ''An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions'' (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include ''A General History of Discoveries and Improvements'' (1727) and ''Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis'' (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement, apart from the novels, is the magisterial ''

Published when Defoe was in his late fifties, ''

Published when Defoe was in his late fifties, ''

Desert island scripts

''

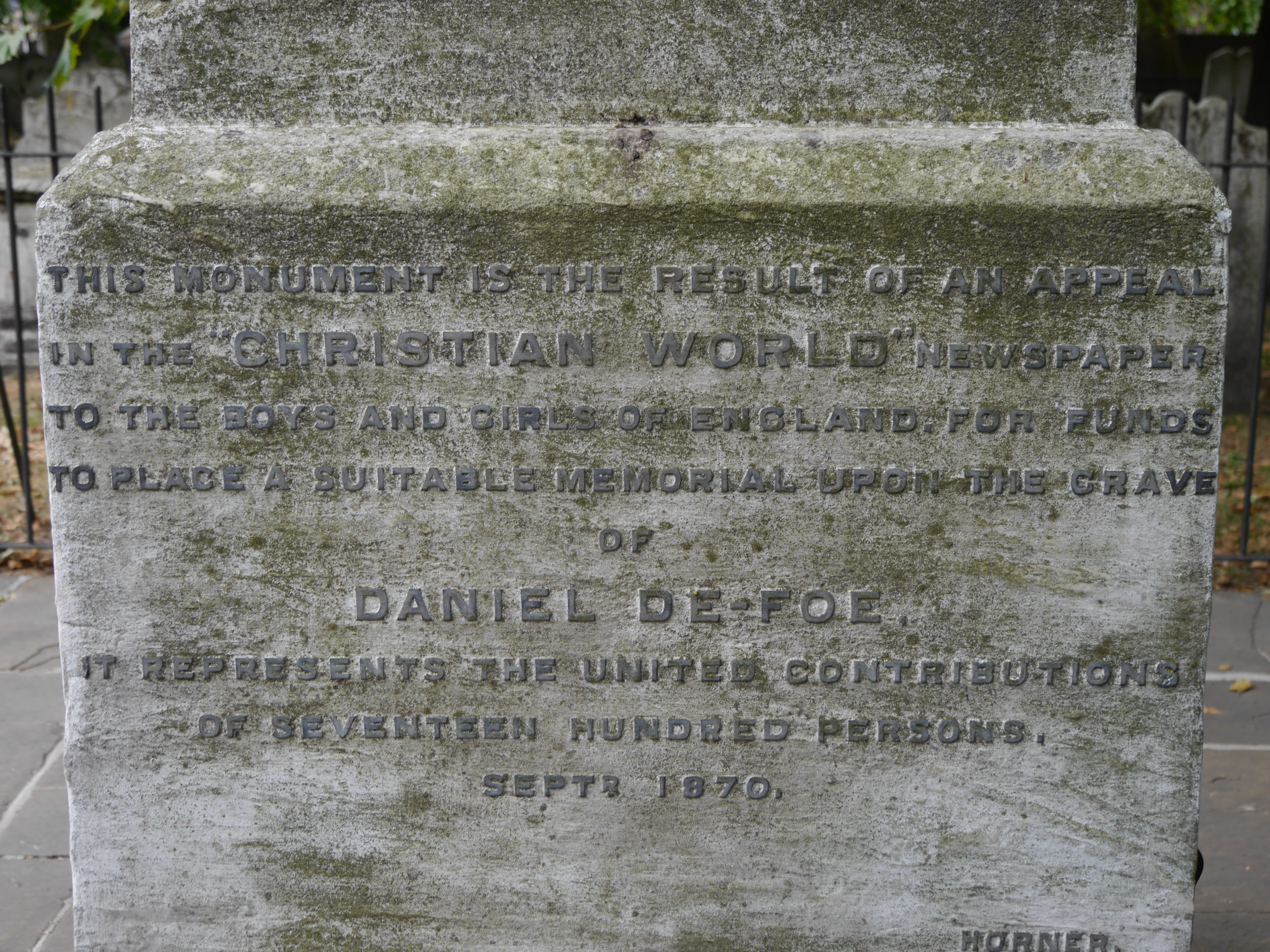

Defoe died on 24 April 1731, probably while in hiding from his creditors. He was often in debtors' prison. The cause of his death was labelled as lethargy, but he probably experienced a stroke. He was interred in Bunhill Fields (today Bunhill Fields Burial and Gardens), just outside the medieval boundaries of the City of London, in what is now the Borough of Islington, where a monument was erected to his memory in 1870.

Defoe died on 24 April 1731, probably while in hiding from his creditors. He was often in debtors' prison. The cause of his death was labelled as lethargy, but he probably experienced a stroke. He was interred in Bunhill Fields (today Bunhill Fields Burial and Gardens), just outside the medieval boundaries of the City of London, in what is now the Borough of Islington, where a monument was erected to his memory in 1870.

''

Full online versions of various copies of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe and the Robinsonades

Full texts in German and English

– eLibrary Projekt (eLib)

The Journeys of Daniel Defoe around Britain

(from a Vision of Britain) * *

Defoe, Daniel 1661?–1731 WorldCat Identity

A System of Magick

''The Thief-Taker Hangings: How Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard Captivated London and Created the Celebrity Criminal'' by Aaron Skirboll

{{DEFAULTSORT:Defoe, Daniel 1660 births 1731 deaths People from Chadwell St Mary People from the City of London 17th-century English people 17th-century spies 18th-century English male writers 18th-century English novelists 18th-century spies Burials at Bunhill Fields English children's writers English essayists English male journalists English male novelists English pamphleteers English Presbyterians English people of Flemish descent English people of French descent English satirists English spies Haberdashers Male essayists Neoclassical writers Anti-contraception activists 18th-century British journalists 17th-century journalists Maritime writers

pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articulate a poli ...

and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translations. He has been seen as one of the earliest proponents of the English novel

The English novel is an important part of English literature. This article mainly concerns novels, written in English, by novelists who were born or have spent a significant part of their lives in England, Scotland, Wales, or Northern Ireland ( ...

, and helped to popularise the form in Britain with others such as Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

and Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of ...

. Defoe wrote many political tracts, was often in trouble with the authorities, and spent a period in prison. Intellectuals and political leaders paid attention to his fresh ideas and sometimes consulted him.

Defoe was a prolific and versatile writer, producing more than three hundred works—books, pamphlets, and journals — on diverse topics, including politics, crime, religion, marriage, psychology, and the supernatural. He was also a pioneer of business journalism

Business journalism is the part of journalism that tracks, records, analyzes and interprets the business, economic and financial activities and changes that take place in societies. Topics widely cover the entire purview of all commercial activ ...

and economic journalism.

Early life

Daniel Foe (his original name) was probably born inFore Street

"Fore Street" is a name often used for the main street of a town or village in Great Britain. Usage is prevalent in the south-west of England, with over seventy "Fore Streets" in Cornwall and about seventy-five in Devon, but it does also occur ...

in the parish of St Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

Cripplegate

Cripplegate was a gate in the London Wall which once enclosed the City of London.

The gate gave its name to the Cripplegate ward of the City which straddles the line of the former wall and gate, a line which continues to divide the ward into tw ...

, London. Defoe later added the aristocratic-sounding "De" to his name, and on occasion made the false claim of descent from a family named De Beau Faux. "De" is also a common prefix in Flemish surnames. His birthdate and birthplace are uncertain, and sources offer dates from 1659 to 1662, with the summer or early autumn of 1660 considered the most likely. His father, James Foe, was a prosperous tallow

Tallow is a rendering (industrial), rendered form of beef or mutton fat, primarily made up of triglycerides.

In industry, tallow is not strictly defined as beef or mutton fat. In this context, tallow is animal fat that conforms to certain techn ...

chandler

Chandler or The Chandler may refer to:

* Chandler (occupation), originally head of the medieval household office responsible for candles, now a person who makes or sells candles

* Ship chandler, a dealer in supplies or equipment for ships

Arts ...

of Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

descent, and a member of the Worshipful Company of Butchers

The Worshipful Company of Butchers is one of the Livery Companies of the City of London, England. Records indicate that an organisation of butchers existed as early as 975; the Butchers' Guild, the direct predecessor of the present Company, was ...

. In Defoe's early childhood, he experienced some of the most unusual occurrences in English history: in 1665, 70,000 were killed by the Great Plague of London

The Great Plague of London, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long Second Pandemic, a period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics that origi ...

, and the next year, the Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London was a major conflagration that swept through central London from Sunday 2 September to Thursday 6 September 1666, gutting the medieval City of London inside the old Roman city wall, while also extending past the ...

left only Defoe's and two other houses standing in his neighbourhood.Richard West (1998) ''Daniel Defoe: The Life and Strange, Surprising Adventures''. New York: Carroll & Graf. . In 1667, when he was probably about seven, a Dutch fleet sailed up the Medway

Medway is a unitary authority district and conurbation in Kent, South East England. It had a population of 278,016 in 2019. The unitary authority was formed in 1998 when Rochester-upon-Medway amalgamated with the Borough of Gillingham to for ...

via the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

and attacked the town of Chatham

Chatham may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions Canada

* Chatham Islands (British Columbia)

* Chatham Sound, British Columbia

* Chatham, New Brunswick, a former town, now a neighbourhood of Miramichi

* Chatham (electoral district), New Brunswic ...

in the raid on the Medway

The Raid on the Medway, during the Second Anglo-Dutch War in June 1667, was a successful attack conducted by the Dutch navy on English warships laid up in the fleet anchorages off Chatham Dockyard and Gillingham in the county of Kent. At the ...

. His mother, Alice, had died by the time he was about ten.

Education

Defoe was educated at the Rev. James Fisher's boarding school in Pixham Lane inDorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England, about south of London. It is in Mole Valley District and the council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs roughly east–west, parallel to the Pipp Br ...

, Surrey. His parents were Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, an ...

, and around the age of 14, he was sent to Charles Morton's dissenting academy

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

at Newington Green

Newington Green is an open space in North London that straddles the border between Islington and Hackney. It gives its name to the surrounding area, roughly bounded by Ball's Pond Road to the south, Petherton Road to the west, Green Lanes and ...

, then a village just north of London, where he is believed to have attended the Dissenting church there. He lived on Church Street, Stoke Newington, at what is now nos. 95–103. During this period, the English government persecuted those who chose to worship outside the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

.

Business career

Defoe entered the world of business as a general merchant, dealing at different times in hosiery, general woollen goods, and wine. His ambitions were great and he was able to buy a country estate and a ship (as well ascivet

A civet () is a small, lean, mostly nocturnal mammal native to tropical Asia and Africa, especially the tropical forests. The term civet applies to over a dozen different species, mostly from the family Viverridae. Most of the species diversit ...

s to make perfume), though he was rarely out of debt. On 1 January 1684, Defoe married Mary Tuffley at St Botolph's Aldgate

St Botolph's Aldgate is a Church of England parish church in the City of London and also, as it lies outside the line of the city's former eastern walls, a part of the East End of London.

The full name of the church is St Botolph without Aldga ...

. She was the daughter of a London merchant, and brought with her a dowry

A dowry is a payment, such as property or money, paid by the bride's family to the groom or his family at the time of marriage. Dowry contrasts with the related concepts of bride price and dower. While bride price or bride service is a payment b ...

of £3,700—a huge amount by the standards of the day. Given his debts and political difficulties, the marriage may have been troubled, but it lasted 47 years and produced eight children.

In 1685, Defoe joined the ill-fated Monmouth Rebellion but gained a pardon, by which he escaped the Bloody Assizes

The Bloody Assizes were a series of trials started at Winchester on 25 August 1685 in the aftermath of the Battle of Sedgemoor, which ended the Monmouth Rebellion in England.

History

There were five judges: Sir William Montague (Lord Chief B ...

of Judge George Jeffreys. Queen Mary and her husband William III were jointly crowned in 1689, and Defoe became one of William's close allies and a secret agent. Some of the new policies led to conflict with France, thus damaging prosperous trade relationships for Defoe. In 1692, he was arrested for debts of £700 and, in the face of total debts that may have amounted to £17,000, was forced to declare bankruptcy. He died with little wealth and evidently embroiled in lawsuits with the royal treasury.

Following his release from debtors’ prison, he probably travelled in Europe and Scotland, and it may have been at this time that he traded wine to Cadiz, Porto

Porto or Oporto () is the second-largest city in Portugal, the capital of the Porto District, and one of the Iberian Peninsula's major urban areas. Porto city proper, which is the entire municipality of Porto, is small compared to its metropol ...

and Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

. By 1695, he was back in England, now formally using the name "Defoe" and serving as a "commissioner of the glass duty", responsible for collecting taxes on bottles. In 1696, he ran a tile and brick factory in what is now Tilbury

Tilbury is a port town in the borough of Thurrock, Essex, England. The present town was established as separate settlement in the late 19th century, on land that was mainly part of Chadwell St Mary. It contains a 16th century fort and an ancie ...

in Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

and lived in the parish of Chadwell St Mary

Chadwell St Mary is an area of the unitary authority of Thurrock in Essex, England. It is one of the traditional (Church of England) parishes in Thurrock and a former civil parish. Its residential areas are on the higher ground overlooking the ...

.

Writing

As many as 545 titles have been attributed to Defoe, including satirical poems, political and religious pamphlets, and volumes.Pamphleteering and prison

Defoe's first notable publication was '' An Essay Upon Projects'', a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a

Defoe's first notable publication was '' An Essay Upon Projects'', a series of proposals for social and economic improvement, published in 1697. From 1697 to 1698, he defended the right of King William III to a standing army

A standing army is a permanent, often professional, army. It is composed of full-time soldiers who may be either career soldiers or conscripts. It differs from army reserves, who are enrolled for the long term, but activated only during wars or n ...

during disarmament, after the Treaty of Ryswick

The Peace of Ryswick, or Rijswijk, was a series of treaties signed in the Dutch city of Rijswijk between 20 September and 30 October 1697. They ended the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War between France and the Grand Alliance (League of Augsburg), Gran ...

(1697) had ended the Nine Years' War

The Nine Years' War (1688–1697), often called the War of the Grand Alliance or the War of the League of Augsburg, was a conflict between France and a European coalition which mainly included the Holy Roman Empire (led by the Habsburg monarch ...

(1688–1697). His most successful poem, ''The True-Born Englishman

''The True-Born Englishman'' is a satirical poem published in 1701 by English writer Daniel Defoe defending King William III, who was Dutch-born, against xenophobic attacks by his political enemies in England. The poem quickly became a bestsell ...

'' (1701), defended William against xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

attacks from his political enemies in England, and English anti-immigration sentiments more generally. In 1701, Defoe presented the ''Legion's Memorial'' to Robert Harley, then Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

—and his subsequent employer—while flanked by a guard of sixteen gentlemen of quality. It demanded the release of the Kentish petitioners, who had asked Parliament to support the king in an imminent war against France.

The death of William III in 1702 once again created a political upheaval, as the king was replaced by Queen Anne who immediately began her offensive against Nonconformists. Defoe was a natural target, and his pamphleteering and political activities resulted in his arrest and placement in a pillory on 31 July 1703, principally on account of his December 1702 pamphlet entitled '' The Shortest-Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church'', purporting to argue for their extermination. In it, he ruthlessly satirised both the high church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

and those Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

s who hypocritically practised so-called "occasional conformity", such as his Stoke Newington

Stoke Newington is an area occupying the north-west part of the London Borough of Hackney in north-east London, England. It is northeast of Charing Cross. The Manor of Stoke Newington gave its name to Stoke Newington the ancient parish.

The ...

neighbour Sir Thomas Abney

Sir Thomas Abney (January 1640 – 6 February 1722) was a merchant and banker who served as Lord Mayor of London for the year 1700 to 1701.

Abney was the son of James Abney and was born in Willesley, then in Derbyshire but now in Leicestershire ...

. It was published anonymously, but the true authorship was quickly discovered and Defoe was arrested. He was charged with seditious libel and found guilty in a trial at the Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

in front of the notoriously sadistic judge Salathiel Lovell

Sir Salathiel Lovell (1631/2–1713) was an English judge, Recorder of London, an ancient and bencher of Gray's Inn, and a Baron of the Exchequer.

Origins and education

Lovell was the son of Benjamin Lovell, rector of Lapworth, Warwickshire, and ...

. Lovell sentenced him to a punitive fine of 200 marks

Marks may refer to:

Business

* Mark's, a Canadian retail chain

* Marks & Spencer, a British retail chain

* Collective trade marks, trademarks owned by an organisation for the benefit of its members

* Marks & Co, the inspiration for the novel ...

(£336 then, £ in ), to public humiliation in a pillory, and to an indeterminate length of imprisonment which would only end upon the discharge of the punitive fine. According to legend, the publication of his poem ''Hymn to the Pillory'' caused his audience at the pillory to throw flowers instead of the customary harmful and noxious objects and to drink to his health. The truth of this story is questioned by most scholars, although John Robert Moore later said that "no man in England but Defoe ever stood in the pillory and later rose to eminence among his fellow men".

After his three days in the pillory, Defoe went into Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

. Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, Order of the Garter, KG Privy Council of Great Britain, PC Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (5 December 1661 – 21 May 1724) was an English statesman and peer of the late Stuart dynasty, Stu ...

, brokered his release in exchange for Defoe's cooperation as an intelligence agent for the Tories. In exchange for such cooperation with the rival political side, Harley paid some of Defoe's outstanding debts, improving his financial situation considerably.

Within a week of his release from prison, Defoe witnessed the Great Storm of 1703

The great storm of 1703 was a destructive extratropical cyclone that struck central and southern England on 26 November 1703. High winds caused 2,000 chimney stacks to collapse in London and damaged the New Forest, which lost 4,000 oaks. Ships wer ...

, which raged through the night of 26/27 November. It caused severe damage to London and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, uprooted millions of trees, and killed more than 8,000 people, mostly at sea. The event became the subject of Defoe's '' The Storm'' (1704), which includes a collection of witness accounts of the tempest. Many regard it as one of the world's first examples of modern journalism.

In the same year, he set up his periodical

A periodical literature (also called a periodical publication or simply a periodical) is a published work that appears in a new edition on a regular schedule. The most familiar example is a newspaper, but a magazine or a journal are also examples ...

''A Review of the Affairs of France'', which supported the Harley Ministry, chronicling the events of the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict that took place from 1701 to 1714. The death of childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700 led to a struggle for control of the Spanish Empire between his heirs, Phil ...

(1702–1714). The ''Review'' ran three times a week without interruption until 1713. Defoe was amazed that a man as gifted as Harley left vital state papers lying in the open, and warned that he was almost inviting an unscrupulous clerk to commit treason; his warnings were fully justified by the William Gregg affair.

When Harley was ousted from the ministry in 1708, Defoe continued writing the ''Review'' to support Godolphin, then again to support Harley and the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

in the Tory ministry of 1710–1714. The Tories fell from power with the death of Queen Anne, but Defoe continued doing intelligence work for the Whig government, writing "Tory" pamphlets that undermined the Tory point of view.

Not all of Defoe's pamphlet writing was political. One pamphlet was originally published anonymously, entitled '' A True Relation of the Apparition of One Mrs. Veal the Next Day after her Death to One Mrs. Bargrave at Canterbury the 8th of September, 1705''. It deals with the interaction between the spiritual realm and the physical realm and was most likely written in support of Charles Drelincourt

Charles Drelincourt (10 July 1595 in Sedan3 November 1669) was a French Protestant divine.

Life

His father, Pierre Drelincourt, fled from Protestant persecution in Caen and became secretary to Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, Duke of Bouillon at S ...

's ''The Christian Defence against the Fears of Death'' (1651). It describes Mrs. Bargrave's encounter with her old friend Mrs. Veal after she had died. It is clear from this piece and other writings that the political portion of Defoe's life was by no means his only focus.

Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

and part instigator of the Darien scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing ''New Caledonia'', a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The plan was for the co ...

, who was in the confidence of Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer, Order of the Garter, KG Privy Council of Great Britain, PC Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS (5 December 1661 – 21 May 1724) was an English statesman and peer of the late Stuart dynasty, Stu ...

, leading minister and spymaster in the English government

There has not been a government of England since 1707 when the Kingdom of England ceased to exist as a sovereign state, as it merged with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.Act of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

.

Defoe began his campaign in ''The Review'' and other pamphlets aimed at English opinion, claiming that it would end the threat from the north, gaining for the Treasury an "inexhaustible treasury of men", a valuable new market increasing the power of England. By September 1706, Harley ordered Defoe to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

as a secret agent to do everything possible to help secure acquiescence in the Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

. He was conscious of the risk to himself. Thanks to books such as ''The Letters of Daniel Defoe'' (edited by G. H. Healey, Oxford 1955), far more is known about his activities than is usual with such agents.

His first reports included vivid descriptions of violent demonstrations against the Union. "A Scots rabble is the worst of its kind", he reported. Years later John Clerk of Penicuik

John Clerk of Penicuik (1611–1674) was a Scottish merchant noted for maintaining a comprehensive archive of family papers, now held by the National Archives of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland.

Background

Born in Montrose, he wa ...

, a leading Unionist, wrote in his memoirs that it was not known at the time that Defoe had been sent by Godolphin :

Defoe was a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

who had suffered in England for his convictions, and as such he was accepted as an adviser to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland

The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland is the sovereign and highest court of the Church of Scotland, and is thus the Church's governing body.''An Introduction to Practice and Procedure in the Church of Scotland'' by A. Gordon McGillivray, ...

and committees of the Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council o ...

. He told Harley that he was "privy to all their folly" but "Perfectly unsuspected as with corresponding with anybody in England". He was then able to influence the proposals that were put to Parliament and reported,

For Scotland, he used different arguments, even the opposite of those which he used in England, usually ignoring the English doctrine of the Sovereignty of Parliament

Parliamentary sovereignty, also called parliamentary supremacy or legislative supremacy, is a concept in the constitutional law of some parliamentary democracies. It holds that the legislative body has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over all ...

, for example, telling the Scots that they could have complete confidence in the guarantees in the Treaty. Some of his pamphlets were purported to be written by Scots, misleading even reputable historians into quoting them as evidence of Scottish opinion of the time. The same is true of a massive history of the Union which Defoe published in 1709 and which some historians still treat as a valuable contemporary source for their own works. Defoe took pains to give his history an air of objectivity by giving some space to arguments against the Union but always having the last word for himself.

He disposed of the main Union opponent, Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun

East Saltoun and West Saltoun are separate villages in East Lothian, Scotland, about 5 miles (8 kilometres) south-west of Haddington and 20 miles (32 kilometres) east of Edinburgh.

Geography

The villages of East Saltoun and West Saltoun, toge ...

, by ignoring him. Nor does he account for the deviousness of the Duke of Hamilton

Duke of Hamilton is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in April 1643. It is the senior dukedom in that peerage (except for the Dukedom of Rothesay held by the Sovereign's eldest son), and as such its holder is the premier peer of Sco ...

, the official leader of the various factions opposed to the Union, who seemingly betrayed his former colleagues when he switched to the Unionist/Government side in the decisive final stages of the debate.

Aftermath

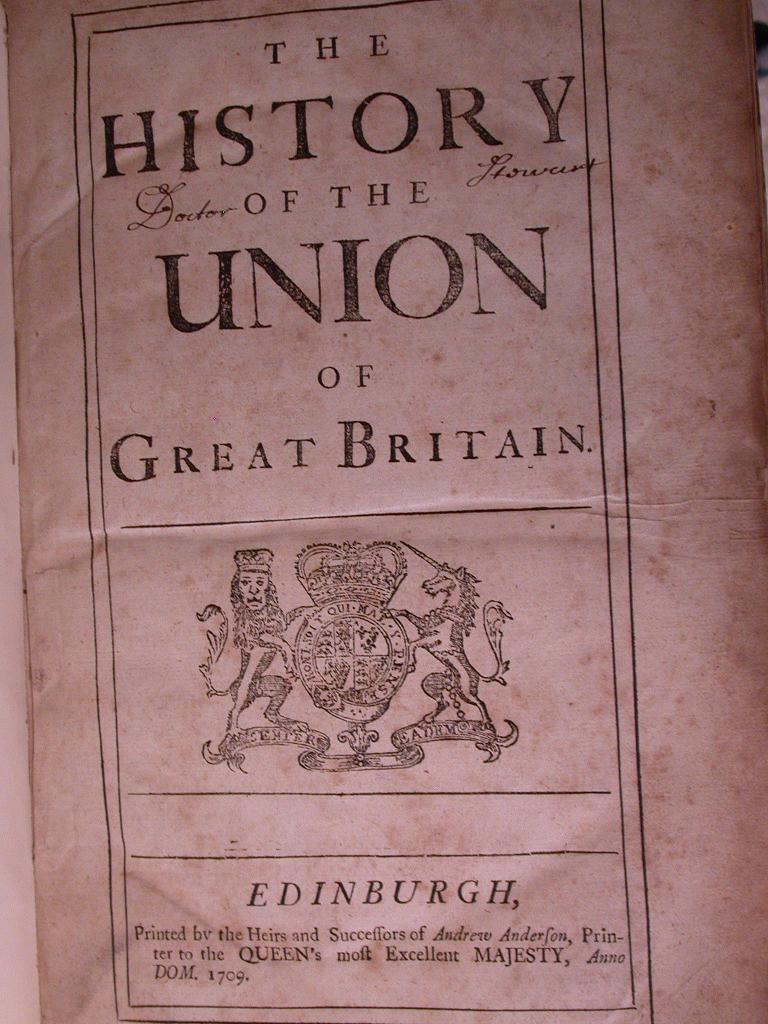

In 1709, Defoe authored a rather lengthy book entitled ''The History of the Union of Great Britain'', an Edinburgh publication printed by the Heirs of Anderson. The book cites Defoe twice as being its author and gives details leading up to the ''Acts of Union 1707

The Acts of Union ( gd, Achd an Aonaidh) were two Acts of Parliament: the Union with Scotland Act 1706 passed by the Parliament of England, and the Union with England Act 1707 passed by the Parliament of Scotland. They put into effect the te ...

'' by means of presenting information that dates all the way back to 6 December 1604 when King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

was presented with a proposal for unification. And so, such so-called "first draft" for unification took place just a little over 100 years before the signing of the 1707 accord, which respectively preceded the commencement of ''Robinson Crusoe'' by another ten years.

Defoe made no attempt to explain why the same Parliament of Scotland which was so vehement for its independence from 1703 to 1705 became so supine in 1706. He received very little reward from his paymasters and of course no recognition for his services by the government. He made use of his Scottish experience to write his ''Tour thro' the whole Island of Great Britain'', published in 1726, where he admitted that the increase of trade and population in Scotland which he had predicted as a consequence of the Union was "not the case, but rather the contrary".

Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

(Glaschu) as a "Dear Green Place" has often been misquoted as a Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

translation for the town's name. The Gaelic ''Glas'' could mean grey or green, while ''chu'' means dog or hollow. ''Glaschu'' probably means "Green Hollow". The "Dear Green Place", like much of Scotland, was a hotbed of unrest against the Union. The local Tron

''Tron'' (stylized as ''TRON'') is a 1982 American science fiction action-adventure film written and directed by Steven Lisberger from a story by Lisberger and Bonnie MacBird. The film stars Jeff Bridges as Kevin Flynn, a computer programmer a ...

minister urged his congregation "to up and anent for the City of God".

The "Dear Green Place" and "City of God" required government troops to put down the rioters tearing up copies of the Treaty at almost every mercat cross in Scotland. When Defoe visited in the mid-1720s, he claimed that the hostility towards his party was "because they were English and because of the Union, which they were almost universally exclaimed against".

Late writing

The extent and particulars are widely contested concerning Defoe's writing in the period from the Tory fall in 1714 to the publication of ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'' in 1719. Defoe comments on the tendency to attribute tracts of uncertain authorship to him in his apologia ''Appeal to Honour and Justice'' (1715), a defence of his part in Harley's Tory ministry (1710–1714). Other works that anticipate his novelistic career include ''The Family Instructor'' (1715), a conduct manual on religious duty; ''Minutes of the Negotiations of Monsr. Mesnager'' (1717), in which he impersonates Nicolas Mesnager

Nicolas Mesnager (or Le Mesnager or Ménager) (1658–1714) was a French diplomat.

Le Mesnager belonged to a wealthy merchant family, forsaking a commercial career, to become a parliamentary lawyer for Rouen under the Ancient régime. In 1700 he ...

, the French plenipotentiary who negotiated the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne o ...

(1713); and ''A Continuation of the Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy

''Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy'' (french: L'Espion Turc) is an eight-volume collection of fictional letters claiming to have been written by an Ottoman spy named "Mahmut", in the French court of Louis XIV.

Authorship and publication

It is agre ...

'' (1718), a satire of European politics and religion, ostensibly written by a Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

in Paris.

From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including ''Religious Courtship'' (1722), ''The Complete English Tradesman'' (1726) and ''The New Family Instructor'' (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as ''The Great Law of Subordination Considered'' (1724) and ''Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business'' (1725) and works on the supernatural, like '' The Political History of the Devil'' (1726), ''A System of Magick'' (1727) and ''An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions'' (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include ''A General History of Discoveries and Improvements'' (1727) and ''Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis'' (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement, apart from the novels, is the magisterial ''

From 1719 to 1724, Defoe published the novels for which he is famous (see below). In the final decade of his life, he also wrote conduct manuals, including ''Religious Courtship'' (1722), ''The Complete English Tradesman'' (1726) and ''The New Family Instructor'' (1727). He published a number of books decrying the breakdown of the social order, such as ''The Great Law of Subordination Considered'' (1724) and ''Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business'' (1725) and works on the supernatural, like '' The Political History of the Devil'' (1726), ''A System of Magick'' (1727) and ''An Essay on the History and Reality of Apparitions'' (1727). His works on foreign travel and trade include ''A General History of Discoveries and Improvements'' (1727) and ''Atlas Maritimus and Commercialis'' (1728). Perhaps his greatest achievement, apart from the novels, is the magisterial ''A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain

''A Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain'' is an account of his travels by English author Daniel Defoe, first published in three volumes between 1724 and 1727. Other than ''Robinson Crusoe'', ''Tour'' was Defoe's most popular and financial ...

'' (1724–1727), which provided a panoramic survey of British trade on the eve of the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

.

''The Complete English Tradesman''

Published in 1726, ''The Complete English Tradesman'' is an example of Defoe's political works. In the work, Defoe discussed the role of thetradesman

A tradesman, tradeswoman, or tradesperson is a skilled worker that specializes in a particular trade (occupation or field of work). Tradesmen usually have work experience, on-the-job training, and often formal vocational education in contrast to ...

in England in comparison to tradesmen internationally, arguing that the British system of trade is far superior. Defoe also implied that trade was the backbone of the British economy

The economy of the United Kingdom is a highly developed social market and market-orientated economy. It is the sixth-largest national economy in the world measured by nominal gross domestic product (GDP), ninth-largest by purchasing power pa ...

: "estate's a pond, but trade's a spring." efoe, Daniel. The complete English tradesman. London: Tegg, 1841. Print./ref> In the work, Defoe praised the practicality of trade not only within the economy but the social stratification as well. Defoe argued that most of the British gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest c ...

was at one time or another inextricably linked with the institution of trade, either through personal experience, marriage or genealogy. Oftentimes younger members of noble families entered into trade, and marriages to a tradesman's daughter by a nobleman

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteris ...

was also common. Overall, Defoe demonstrated a high respect for tradesmen, being one himself.

Not only did Defoe elevate individual British tradesmen to the level of gentleman, but he praised the entirety of British trade as a superior system to other systems of trade. Trade, Defoe argues, is a much better catalyst for social and economic change than war. Defoe also argued that through the expansion of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and British mercantile influence, Britain would be able to "increase commerce at home" through job creations and increased consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

. He wrote in the work that increased consumption, by laws of supply and demand, increases production and in turn raises wages for the poor therefore lifting part of British society further out of poverty.

Novels

''Robinson Crusoe''

Published when Defoe was in his late fifties, ''

Published when Defoe was in his late fifties, ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'' relates the story of a man's shipwreck on a desert island for twenty-eight years and his subsequent adventures. Throughout its episodic narrative, Crusoe's struggles with faith are apparent as he bargains with God in times of life-threatening crises, but time and again he turns his back after his deliverances. He is finally content with his lot in life, separated from society, following a more genuine conversion experience.

In the opening pages of ''The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

''The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'' (now more commonly rendered as ''The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'') is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1719. Just as in its significantly more popular predecessor, ''Robinson C ...

'', the author describes how Crusoe settled in Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council wa ...

, married and produced a family, and that when his wife died, he went off on these further adventures. Bedford is also the place where the brother of "H. F." in ''A Journal of the Plague Year'' retired to avoid the danger of the plague, so that by implication, if these works were not fiction, Defoe's family met Crusoe in Bedford, from whence the information in these books was gathered. Defoe went to school Newington Green with a friend named Caruso.

The novel has been assumed to be based in part on the story of the Scottish castaway Alexander Selkirk

Alexander Selkirk (167613 December 1721) was a Scottish privateer and Royal Navy officer who spent four years and four months as a castaway (1704–1709) after being marooned by his captain, initially at his request, on an uninhabited island i ...

, who spent four years stranded in the Juan Fernández Islands

The Juan Fernández Islands ( es, Archipiélago Juan Fernández) are a sparsely inhabited series of islands in the South Pacific Ocean reliant on tourism and fishing. Situated off the coast of Chile, they are composed of three main volcanic i ...

, but his experience is inconsistent with the details of the narrative. The island Selkirk lived on, Más a Tierra (Closer to Land) was renamed Robinson Crusoe Island

Robinson Crusoe Island ( es, Isla Róbinson Crusoe, ), formerly known as Más a Tierra (), is the second largest of the Juan Fernández Islands, situated 670 km (362 nmi; 416 mi) west of San Antonio, Chile, in the South Pacific Oc ...

in 1966. It has been supposed that Defoe may have also been inspired by a translation of a book by the Andalusian-Arab Muslim polymath Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theolo ...

, who was known as "Abubacer" in Europe. The Latin edition was entitled ''Philosophus Autodidactus

''Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān'' () is an Arabic philosophical novel and an allegorical tale written by Ibn Tufail (c. 1105 – 1185) in the early 12th century in Al-Andalus. Names by which the book is also known include the ('The Self-Taught Philosop ...

'';Martin Wainwright (22 March 2003Desert island scripts

''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

''. Simon Ockley

Simon Ockley (16789 August 1720) was a British Orientalist.

Biography

Ockley was born at Exeter. He was educated at Queens' College, Cambridge, and graduated B.A. in 1697, MA. in 1701, and B.D. in 1710. He became fellow of Jesus College and vi ...

published an English translation in 1708, entitled ''The improvement of human reason, exhibited in the life of Hai ebn Yokdhan''.

''Captain Singleton''

Defoe's next novel was ''Captain Singleton

''The Life, Adventures and Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, originally published in 1720. It has been re-published multiple times since, some of which times were in 1840 1927, 1972 and 2008. ''Captain Si ...

'' (1720), an adventure story whose first half covers a traversal of Africa which anticipated subsequent discoveries by David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

and whose second half taps into the contemporary fascination with piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

. The novel has been commended for its sensitive depiction of the close relationship between the hero and his religious mentor, Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

William Walters. Its description of the geography of Africa and some of its fauna does not use the language or knowledge of a fiction writer and suggests an eyewitness experience.

''Memoirs of a Cavalier''

'' Memoirs of a Cavalier'' (1720) is set during theThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (80 ...

and the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

.

''A Journal of the Plague Year''

'' A Journal of the Plague Year'', published in 1722, can be read both as novel and as nonfiction. It is an account of theGreat Plague of London

The Great Plague of London, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long Second Pandemic, a period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics that origi ...

in 1665, which is undersigned by the initials "H. F.", suggesting the author's uncle Henry Foe as its primary source. It is a historical account of the events based on extensive research and written as if by an eyewitness, even though Defoe was only about five years old when it occurred.

''Colonel Jack''

''Colonel Jack

''Colonel Jack'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. The considerably longer title under which it was originally published is ''The History and Remarkable Life of the truly Honourable Col. Jacque, commonly call'd Col. Jack, who ...

'' (1722) follows an orphaned boy from a life of poverty and crime to prosperity in the colonies, military and marital imbroglios, and religious conversion, driven by a problematic notion of becoming a "gentleman."

''Moll Flanders''

Also in 1722, Defoe wrote ''Moll Flanders

''Moll Flanders'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, wit ...

'', another first-person picaresque novel

The picaresque novel ( Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for "rogue" or "rascal") is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish, but "appealing hero", usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corru ...

of the fall and eventual redemption, both material and spiritual, of a lone woman in 17th-century England. The titular heroine appears as a whore, bigamist, and thief, lives in The Mint, commits adultery and incest, and yet manages to retain the reader's sympathy. Her savvy manipulation of both men and wealth earns her a life of trials but ultimately an ending in reward. Although Moll struggles with the morality of some of her actions and decisions, religion seems to be far from her concerns throughout most of her story. However, like Robinson Crusoe, she finally repents. ''Moll Flanders'' is an important work in the development of the novel, as it challenged the common perception of femininity and gender roles in 18th-century British society. More recently it has come to be misunderstood as an example of erotica

Erotica is literature or art that deals substantively with subject matter that is erotic, sexually stimulating or sexually arousing. Some critics regard pornography as a type of erotica, but many consider it to be different. Erotic art may use ...

.

''Roxana''

Defoe's final novel, '' Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress'' (1724), which narrates the moral and spiritual decline of a high society courtesan, differs from other Defoe works because the main character does not exhibit a conversion experience, even though she claims to be a penitent later in her life, at the time that she is relating her story.Patterns

In Defoe's writings, especially in his fiction, are traits that can be seen across his works. Defoe was well known for hisdidacticism

Didacticism is a philosophy that emphasizes instructional and informative qualities in literature, art, and design. In art, design, architecture, and landscape, didacticism is an emerging conceptual approach that is driven by the urgent need to ...

, with most of his works aiming to convey a message of some kind to the readers (typically a moral one, stemming from his religious background). Connected to Defoe's didacticism is his use of the genre of spiritual autobiography

Spiritual autobiography is a genre of non-fiction prose that dominated Protestant writing during the seventeenth century, particularly in England, particularly that of Dissenters. The narrative follows the believer from a state of damnation to a s ...

, particularly in ''Robinson Crusoe''. Another common feature of Defoe's fictional works is that he claimed them to be the true stories of their subjects.

Attribution and de-attribution

Defoe is known to have used at least 198pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

s. It was a very common practice in eighteenth-century novel publishing to initially publish works under a pen name, with most other authors at the time publishing their works anonymously. As a result of the anonymous ways in which most of his works were published, it has been a challenge for scholars over the years to properly credit Defoe for all of the works that he wrote in his lifetime. If counting only works that Defoe published under his own name, or his known pen name "the author of the True-Born Englishman," there would be about 75 works that could be attributed to him.

Beyond these 75 works, scholars have used a variety of strategies to determine what other works should be attributed to Defoe. Writer George Chalmers was the first to begin the work of attributing anonymously published works to Defoe. In ''History of the Union'', he created an expanded list with over a hundred titles that he attributed to Defoe, alongside twenty additional works that he designated as "Books which are supposed to be De Foe's." Chalmers included works in his canon of Defoe that were particularly in line with his style and way of thinking, and ultimately attributed 174 works to Defoe.

Biographer P. N. Furbank and W. R. Owens built upon this canon, also relying on what they believed could be Defoe's work, without a means to be absolutely certain. In the ''Cambridge History of English Literature'', the section on Defoe by author William P. Trent attributes 370 works to Defoe. J.R. Moore generated the largest list of Defoe's work, with approximately five hundred and fifty works that he attributed to Defoe.

Death

Selected works

Novels

* '' The Consolidator, or Memoirs of Sundry Transactions from the World in the Moon: Translated from the Lunar Language'' (1705)"Defoe, Daniel"''

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction

''The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction'' (SFE) is an English language reference work on science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and f ...

''. Online edition (3rd ed., 2011). Biographical entry by editors John Clute and Peter Nicholls. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

* ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'' (1719) – originally published in two volumes:

** ''The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner: Who Lived Eight and Twenty Years ..'

** ''The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe

''The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'' (now more commonly rendered as ''The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe'') is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1719. Just as in its significantly more popular predecessor, ''Robinson C ...

: Being the Second and Last Part of His Life ..'

* '' Serious Reflections During the Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe: With his Vision of the Angelick World'' (1720)

* ''Captain Singleton

''The Life, Adventures and Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, originally published in 1720. It has been re-published multiple times since, some of which times were in 1840 1927, 1972 and 2008. ''Captain Si ...

'' (1720)

* '' Memoirs of a Cavalier'' (1720)

* '' A Journal of the Plague Year'' (1722)

* ''Colonel Jack

''Colonel Jack'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. The considerably longer title under which it was originally published is ''The History and Remarkable Life of the truly Honourable Col. Jacque, commonly call'd Col. Jack, who ...

'' (1722)

* ''Moll Flanders

''Moll Flanders'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, wit ...

'' (1722)

* '' Roxana: The Fortunate Mistress'' (1724)

Nonfiction

* '' An Essay Upon Projects'' (1697) – subsections of the text include: "The History of Projects," "Of Projectors," "Of Banks," "Of the Highways," "Of Assurances," "Of Friendly Societies," "The Proposal is for a Pension Office," "Of Wagering," "Of Fools," "A Charity-Lottery," "Of Bankrupts," "Of Academies" (including a section proposing an academy for women), "Of a Court Merchant," and "Of Seamen." * '' The Storm'' (1704) – describes the worst storm ever to hit Britain in recorded times. Includes eyewitness accounts. * '' Atlantis Major'' (1711) * '' The Family Instructor'' (1715) * '' Memoirs of the Church of Scotland'' (1717) * '' The History of the Remarkable Life of John Sheppard'' (1724) – describing Sheppard's life of crime and concluding with the miraculous escapes from prison for which he had become a public sensation. * '' A Narrative of All The Robberies, Escapes, &c. of John Sheppard'' (1724) – written by or taken from Sheppard himself in the condemned cell before he was hanged for theft, apparently by way of conclusion to the Defoe work. According to the Introduction to Volume 16 of the works of Defoe published by J M Dent in 1895, Sheppard handed the manuscript to the publisher Applebee from the prisoners' cart as he was taken away to be hanged. It included a correction of a factual detail and an explanation of how his escapes from prison were achieved. * ''A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies

''A Tour Thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain'' is an account of his travels by English author Daniel Defoe, first published in three volumes between 1724 and 1727. Other than ''Robinson Crusoe'', ''Tour'' was Defoe's most popular and financia ...

'' (1724–1727)

* ''A New Voyage Round the World'' (1724)

* '' The Political History of the Devil'' (1726)

* '' The Complete English Tradesman'' (1726)

* '' A treatise concerning the use and abuse of the marriage bed... (1727)''

* '' A Plan of the English Commerce'' (1728) – describes how the English woolen textile industrial base was developed by protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

policies by Tudor monarchs, especially by Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 – 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beaufort ...

and Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

, including such policies as high tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

s on the importation of finished woolen goods, high taxes on raw wool leaving England, bringing in artisans skilled in wool textile manufacturing from the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, selective government-granted monopoly

economics, a government-granted monopoly (also called a "de jure monopoly" or "regulated monopoly") is a form of coercive monopoly by which a government grants exclusive privilege to a private individual or firm to be the sole provider of a good ...

rights, and government-sponsored industrial espionage.

Pamphlets or essays in prose

* '' The Poor Man's Plea'' (1698) * '' The History of the Kentish Petition'' (1701) * '' The Shortest Way with the Dissenters'' (1702) * '' The Great Law of Subordination Consider'd'' (1704) * '' Giving Alms No Charity, and Employing the Poor'' (1704) * '' The Apparition of Mrs. Veal'' (1706) * '' An Appeal to Honour and Justice, Tho' it be of his Worst Enemies, by Daniel Defoe, Being a True Account of His Conduct in Publick Affairs'' (1715) * ''A Vindication of the Press: Or, An Essay on the Usefulness of Writing, on Criticism, and the Qualification of Authors'' (1718) * '' Every-body's Business, Is No-body's Business'' (1725) * '' The Protestant Monastery'' (1726) * '' Parochial Tyranny'' (1727) * '' Augusta Triumphans'' (1728) * '' Second Thoughts are Best'' (1729) * '' An Essay Upon Literature'' (1726) * ''Mere Nature Delineated

''Mere Nature Delineated'' is a pamphlet by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1726.Novak 2009, p. 40. The longer title under which it was originally published is ''Mere nature delineated: or, A body without a soul. Being observations upon the youn ...

'' (1726)

* '' Conjugal Lewdness'' (1727) – Anti-Contraception Essay

Pamphlets or essays in verse

* ''The True-Born Englishman

''The True-Born Englishman'' is a satirical poem published in 1701 by English writer Daniel Defoe defending King William III, who was Dutch-born, against xenophobic attacks by his political enemies in England. The poem quickly became a bestsell ...

: A Satyr'' (1701)

* ''Hymn to the Pillory'' (1703)

* ''An Essay on the Late Storm'' (1704)

Some contested works attributed to Defoe

* '' A Friendly Epistle by way of reproof from one of the people called Quakers, to T. B., a dealer in many words'' (1715). * '' The King of Pirates'' (1719) – purporting to be an account of the pirateHenry Avery

Henry Every, also known as Henry Avery (20 August 1659after 1696), sometimes erroneously given as Jack Avery or John Avery, was an English pirate who operated in the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the mid-1690s. He probably used several aliases ...

.

* '' The Pirate Gow'' (1725) – an account of John Gow

John Gow (c. 1698–11 June 1725) was a notorious pirate whose short career was immortalised by Charles Johnson in the 1725 work ''The History and Lives of All the Most Notorious Pirates and Their Crews''. Little is known of his life, except f ...

.

* ''A General History of the Pyrates

''A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates'' is a 1724 book published in Britain containing biographies of contemporary pirates,

'' (1724, 1725, 1726, 1828) – published in two volumes by Charles Rivington, who had a shop near St. Paul's Cathedral, London. Published under the name of Captain Charles Johnson

Captain Charles Johnson was the British author of the 1724 book ''A General History of the Pyrates, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates'', whose identity remains a mystery. No record exists of a captain b ...

, it sold in many editions.

* Captain Carleton's ''Memoirs of an English Officer'' (1728).

* '' The life and adventures of Mrs. Christian Davies, commonly call'd Mother Ross'' (1740) – published anonymously; printed and sold by R. Montagu in London; and attributed to Defoe but more recently not accepted.

See also

*Apprentice complex The apprentice complex is a psychodynamic constellation whereby a boy or youth resolves the Oedipus complex by an identification with his father, or father figure, as someone from whom to learn the future secrets of masculinity.

The term was introd ...

* Moubray House

Moubray House, 51 and 53 High Street, is one of the oldest buildings on the Royal Mile, and one of the oldest occupied residential buildings in Edinburgh, Scotland. The façade dates from the early 17th century, built on foundations laid .

The t ...

Notes

References

Further reading

* Backscheider, Paula R. ''Daniel Defoe: His Life'' (1989). * Backscheider, Paula R. ''Daniel Defoe: Ambition and Innovation'' (UP of Kentucky, 2015). * Baines, Paul. ''Daniel Defoe-Robinson Crusoe/Moll Flanders'' (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). * * * * Gregg, Stephen H. ''Defoe's Writings and Manliness: Contrary Men'' (Routledge, 2016). * Guilhamet, Leon. ''Defoe and the Whig Novel: A Reading of the Major Fiction'' (U of Delaware Press, 2010). * Hammond, John R. ed. ''A Defoe companion'' (Macmillan, 1993). * * Novak, Maximillian E. ''Daniel Defoe: Master of Fictions: His Life and Ideas'' (2001) * * Novak, Maximillian E. ''Realism, myth, and history in Defoe's fiction'' (U of Nebraska Press, 1983). * Richetti, John. ''The Life of Daniel Defoe: A Critical Biography'' (2015). * * Sutherland, J.R. ''Defoe'' (Taylor & Francis, 1950)Primary sources

* Curtis, Laura Ann, ed. ''The Versatile Defoe: An Anthology of Uncollected Writings by Daniel Defoe'' (Rowman and Littlefield, 1979). * Defoe, Daniel. ''The Best of Defoe's Review: An Anthology'' (Columbia University Press, 1951). * W. R. Owens, and Philip Nicholas Furbank, eds. ''The True-Born Englishman and Other Writings'' (Penguin Books, 1997). * W. R. Owens, and Philip Nicholas Furbank, eds. ''Political and Economic Writings of Daniel Defoe'' (Pickering & Chatto, 2000). * W. R. Owens, and Philip Nicholas Furbank, eds. ''Writings on Travel, Discovery, and History'' (Pickering & Chatto, 2001–2002).External links

* * * * *Full online versions of various copies of Defoe's Robinson Crusoe and the Robinsonades

Full texts in German and English

– eLibrary Projekt (eLib)

The Journeys of Daniel Defoe around Britain

(from a Vision of Britain) * *

Defoe, Daniel 1661?–1731 WorldCat Identity

A System of Magick

''The Thief-Taker Hangings: How Daniel Defoe, Jonathan Wild, and Jack Sheppard Captivated London and Created the Celebrity Criminal'' by Aaron Skirboll

{{DEFAULTSORT:Defoe, Daniel 1660 births 1731 deaths People from Chadwell St Mary People from the City of London 17th-century English people 17th-century spies 18th-century English male writers 18th-century English novelists 18th-century spies Burials at Bunhill Fields English children's writers English essayists English male journalists English male novelists English pamphleteers English Presbyterians English people of Flemish descent English people of French descent English satirists English spies Haberdashers Male essayists Neoclassical writers Anti-contraception activists 18th-century British journalists 17th-century journalists Maritime writers