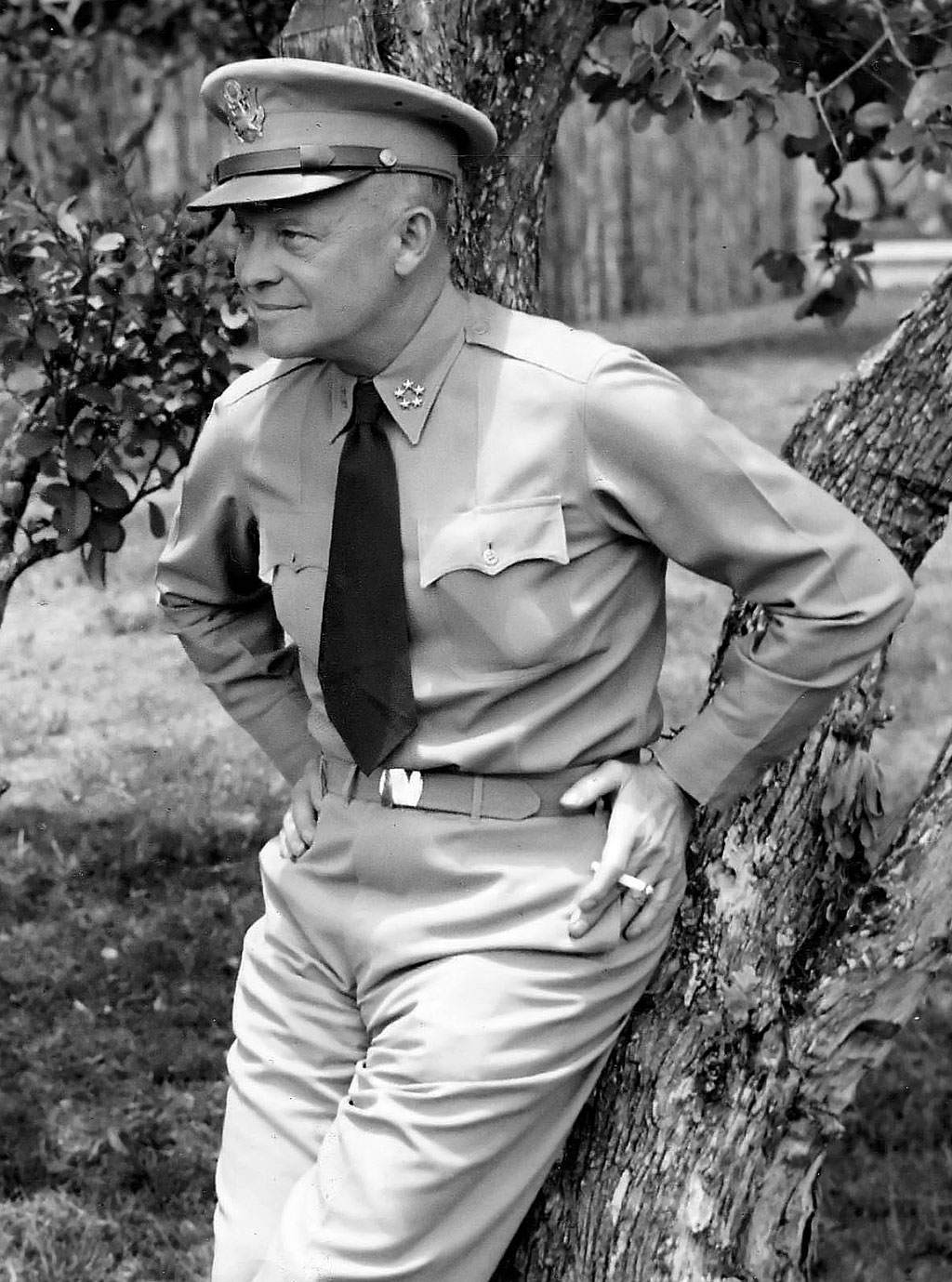

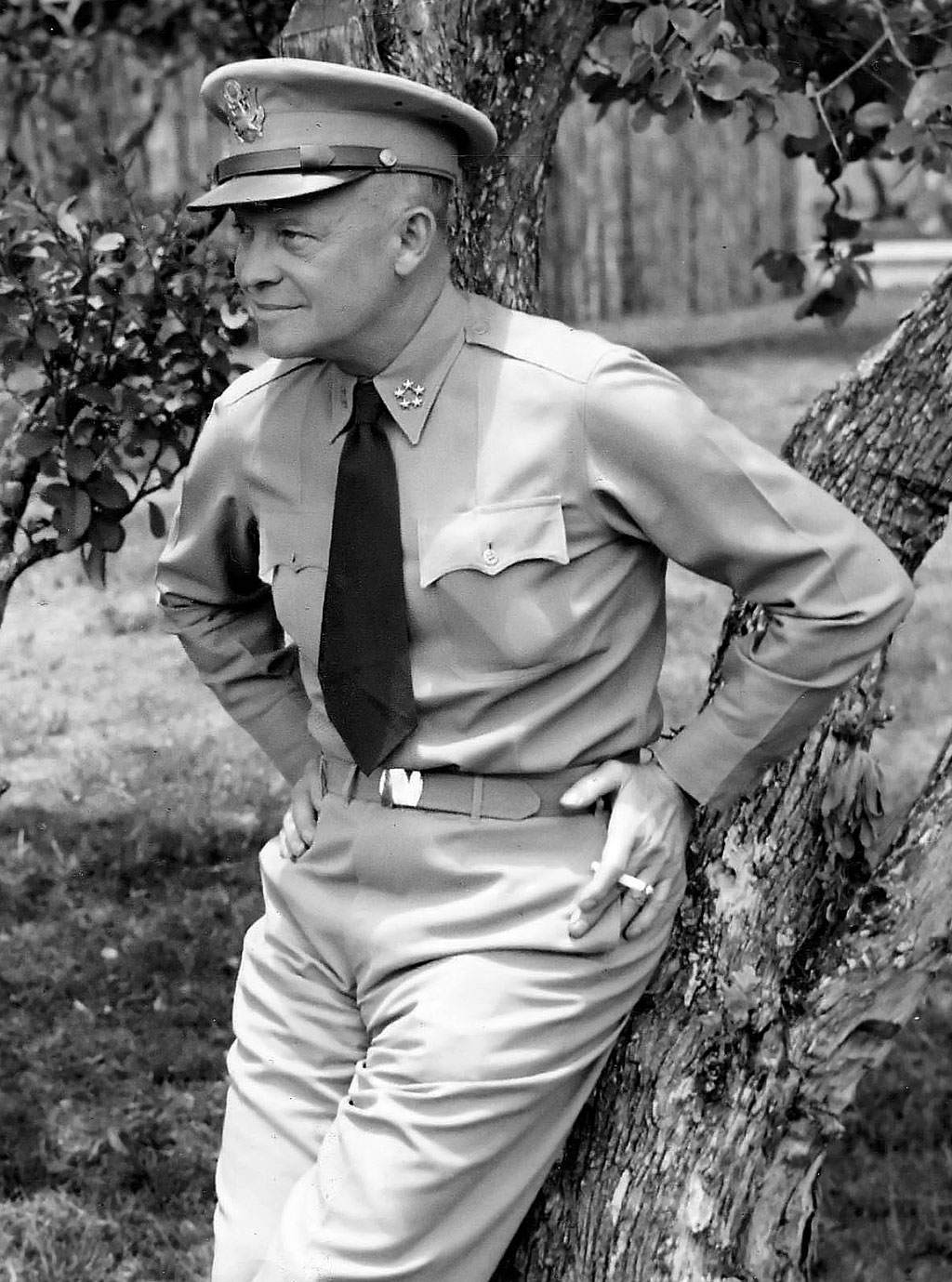

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American

military officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent context ...

and statesman who served as the 34th

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

from 1953 to 1961. During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, he served as

Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and achieved the

five-star rank

A five-star rank is the highest military rank in many countries.Oxford English Dictionary (OED), 2nd Edition, 1989. "five" ... "five-star adj., ... (b) U.S., applied to a general or admiral whose badge of rank includes five stars;" The rank is t ...

of

General of the Army. He planned and supervised the invasion of North Africa in

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while al ...

in 1942–1943 as well as the

invasion of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful invasion of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the Norm ...

(

D-Day

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

) from the

Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

in 1944–1945.

Eisenhower was born into a large family of mostly

Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

ancestry in

Denison, Texas

Denison is a city in Grayson County, Texas, United States. It is south of the Texas–Oklahoma border. The population was 22,682 at the 2010 census. Denison is part of the Texoma region and is one of two principal cities in the Sherman–Deni ...

, and raised in

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum and the ...

. His family had a strong religious background, and his mother became a

Jehovah's Witness

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

. Eisenhower, however, belonged to no organized church until 1952. He graduated from

West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

in 1915 and later married

Mamie Doud

Mary Geneva "Mamie" Eisenhower (; November 14, 1896 – November 1, 1979) was the first lady of the United States from 1953 to 1961 as the wife of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Born in Boone, Iowa, she was raised in a wealthy household in ...

, with whom he had two sons. During

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he was denied a request to serve in Europe and instead commanded a unit that trained tank crews. Following the war, he served under various generals and was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in 1941. After the United States entered World War II, Eisenhower oversaw the invasions of North Africa and Sicily before supervising the invasions of France and Germany. After the war, he served as Army Chief of Staff (1945–1948), as president of

Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

(1948–1953) and as the first

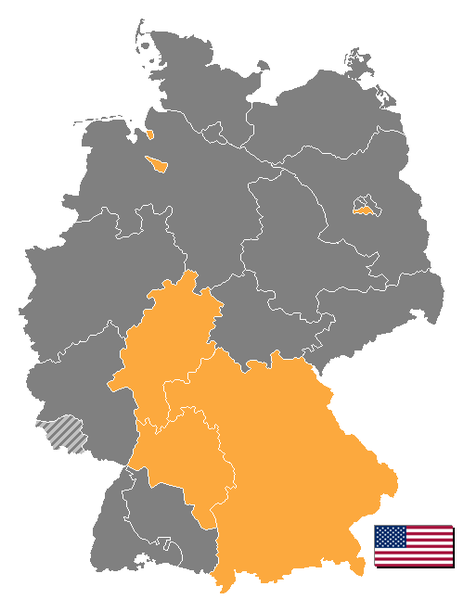

Supreme Commander of NATO (1951–1952).

In 1952, Eisenhower entered the presidential race as a

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

to block the isolationist foreign policies of Senator

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

, who opposed

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

and wanted no foreign entanglements. Eisenhower won

that election and the

1956 election in landslides, both times defeating

Adlai Stevenson II

Adlai Ewing Stevenson II (; February 5, 1900 – July 14, 1965) was an American politician and diplomat who was twice the Democratic nominee for President of the United States. He was the grandson of Adlai Stevenson I, the 23rd vice president o ...

. Eisenhower's main goals in office were to contain the spread of

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

and reduce federal deficits. In 1953, he considered using nuclear weapons to end the

Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top:{ ...

and may have threatened China with nuclear attack if an armistice was not reached quickly. China did agree and

an armistice resulted, which remains in effect. His

New Look policy of nuclear deterrence prioritized "inexpensive" nuclear weapons while reducing funding for expensive Army divisions. He continued

Harry S. Truman's policy of recognizing

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the no ...

as the legitimate government of China, and he won congressional approval of the

Formosa Resolution. His administration provided major aid to help the French fight off Vietnamese Communists in the

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

. After the French left, he gave strong financial support to the new state of

South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

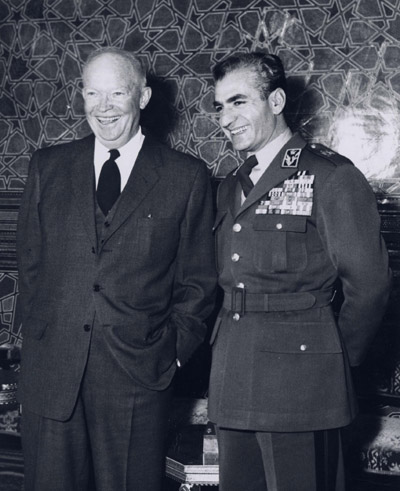

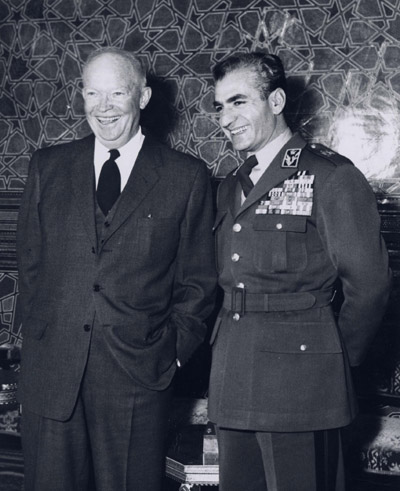

. He supported regime-changing military coups in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and

Guatemala

Guatemala ( ; ), officially the Republic of Guatemala ( es, República de Guatemala, links=no), is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico; to the northeast by Belize and the Caribbean; to the east by Hon ...

orchestrated by his own administration. During the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of 1956, he condemned the Israeli, British, and French invasion of Egypt, and he forced them to withdraw. He also condemned the Soviet invasion during the

Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

but took no action. He deployed 15,000 soldiers during the

1958 Lebanon crisis

The 1958 Lebanon crisis (also known as the Lebanese Civil War of 1958) was a political crisis in Lebanon caused by political and religious tensions in the country that included a United States military intervention. The intervention lasted for aro ...

. Near the end of his term, he failed to set up a summit meeting with the Soviets when a

U.S. spy plane was shot down over the Soviet Union. He approved the

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly fin ...

, which was left to

John F. Kennedy to carry out.

On the domestic front, Eisenhower governed as a moderate conservative who continued

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Con ...

agencies and expanded

Social Security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifical ...

. He covertly opposed

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican United States Senate, U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarth ...

and contributed to the end of

McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

by openly invoking

executive privilege

Executive privilege is the right of the president of the United States and other members of the executive branch to maintain confidential communications under certain circumstances within the executive branch and to resist some subpoenas and othe ...

. He signed the

Civil Rights Act of 1957

The Civil Rights Act of 1957 was the first federal civil rights legislation passed by the United States Congress since the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The bill was passed by the 85th United States Congress and signed into law by President Dwi ...

and sent Army troops to enforce federal court orders which integrated schools in

Little Rock, Arkansas

( The "Little Rock")

, government_type = Council-manager

, leader_title = Mayor

, leader_name = Frank Scott Jr.

, leader_party = D

, leader_title2 = Council

, leader_name2 ...

. His administration undertook the development and construction of the

Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. T ...

, which remains the largest construction of roadways in American history. In 1957, following the Soviet launch of

Sputnik

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for ...

, Eisenhower led the American response which included the creation of

NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeedin ...

and the establishment of a stronger, science-based education via the

National Defense Education Act

The National Defense Education Act (NDEA) was signed into law on September 2, 1958, providing funding to United States education institutions at all levels.Schwegler 1

NDEA was among many science initiatives implemented by President Dwight D. ...

. Following the establishment of NASA, the Soviet Union began to reinforce their own space program, escalating the

Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the t ...

. His two terms saw

unprecedented economic prosperity except for a

minor recession in 1958. In his

farewell address to the nation, he expressed his concerns about the dangers of massive military spending, particularly

deficit spending

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit; the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budget ...

and government contracts to private military manufacturers, which he dubbed "the

military–industrial complex

The expression military–industrial complex (MIC) describes the relationship between a country's military and the defense industry that supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy. A driving factor behind the ...

". Historical evaluations of his presidency place him among the

upper tier of American presidents.

Family background

The Eisenhauer (German for "iron hewer or "iron miner") family migrated from the German village of

Karlsbrunn to the

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to Wi ...

in 1741, initially settling in

York, Pennsylvania

York (Pennsylvania Dutch: ''Yarrick''), known as the White Rose City (after the symbol of the House of York), is the county seat of York County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is located in the south-central region of the state. The populatio ...

. The family moved to Kansas in the 1880s.

Accounts vary as to how and when the German name Eisenhauer was

anglicized

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influenc ...

to Eisenhower. Eisenhower's

Pennsylvania Dutch

The Pennsylvania Dutch ( Pennsylvania Dutch: ), also known as Pennsylvania Germans, are a cultural group formed by German immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. They emigrated primarily from German-spe ...

ancestors, who were primarily farmers, included Hans Nikolaus Eisenhauer of Karlsbrunn, who migrated in 1741 to

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Lancaster, ( ; pdc, Lengeschder) is a city in and the county seat of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. It is one of the oldest inland cities in the United States. With a population at the 2020 census of 58,039, it ranks 11th in population amon ...

.

Hans's great-great-grandson, David Jacob Eisenhower (1863–1942), Eisenhower's father, was a college-educated engineer, despite his own father Jacob's urging to stay on the family farm. Eisenhower's mother,

Ida Elizabeth (Stover) Eisenhower, born in Virginia, of predominantly German Protestant ancestry, moved to Kansas from Virginia. She married David on September 23, 1885, in

Lecompton, Kansas, on the campus of their alma mater,

Lane University.

Dwight David Eisenhower's lineage also included English ancestors (on both sides) and Scottish ancestors (through his maternal line).

David owned a general store in

Hope, Kansas, but the business failed due to economic conditions and the family became impoverished. The Eisenhowers then lived in Texas from 1889 until 1892, and later returned to Kansas, with $24 () to their name at the time. David worked as a railroad mechanic and then at a creamery.

By 1898, the parents made a decent living and provided a suitable home for their large family.

Early life and education

Eisenhower was born David Dwight Eisenhower in

Denison, Texas

Denison is a city in Grayson County, Texas, United States. It is south of the Texas–Oklahoma border. The population was 22,682 at the 2010 census. Denison is part of the Texoma region and is one of two principal cities in the Sherman–Deni ...

, on October 14, 1890, the third of seven sons born to

Ida Stover and David J. Eisenhower. His mother soon reversed his two forenames after his birth to avoid the confusion of having two Davids in the family.

All of the boys were nicknamed "Ike", such as "Big Ike" (

Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

) and "Little Ike" (Eisenhower); the nickname was intended as an abbreviation of their last name. By

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, only Eisenhower was still called "Ike".

In 1892, the family moved to

Abilene, Kansas

Abilene (pronounced ) is a city in, and the county seat of, Dickinson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 6,460. It is home of The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum and the ...

, which Eisenhower considered his hometown. As a child, he was involved in an accident that cost his younger brother

Earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particu ...

an eye, for which he was remorseful for the remainder of his life. Eisenhower developed a keen and enduring interest in exploring the outdoors. He learned about hunting and fishing, cooking, and card playing from an illiterate man named Bob Davis who camped on the

Smoky Hill River

The Smoky Hill River is a river in the central Great Plains of North America, running through Colorado and Kansas.Smoky Hill River. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 22, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.br ...

.

While his mother was against war, it was her collection of history books that first sparked Eisenhower's early and lasting interest in military history. He persisted in reading the books in her collection and became a voracious reader on the subject. Other favorite subjects early in his education were arithmetic and spelling.

His parents set aside specific times at breakfast and at dinner for daily family Bible reading. Chores were regularly assigned and rotated among all the children, and misbehavior was met with unequivocal discipline, usually from David. His mother, previously a member (with David) of the

River Brethren

The River Brethren are a group of historically related Anabaptist Christian denominations originating in 1770, during the Radical Pietist movement among German colonists in Pennsylvania. In the 17th century, Mennonite refugees from Switzerlan ...

sect of the

Mennonite

Mennonites are groups of Anabaptist Christian church communities of denominations. The name is derived from the founder of the movement, Menno Simons (1496–1561) of Friesland. Through his writings about Reformed Christianity during the R ...

s, joined the

International Bible Students Association

A number of corporations are in use by Jehovah's Witnesses. They publish literature and perform other operational and administrative functions, representing the interests of the religious organization. "The Society" has been used as a collective ...

, later known as

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses is a millenarian restorationist Christian denomination with nontrinitarian beliefs distinct from mainstream Christianity. The group reports a worldwide membership of approximately 8.7 million adherents involved in ...

. The Eisenhower home served as the local meeting hall from 1896 to 1915, though Eisenhower never joined the International Bible Students. His later decision to attend West Point saddened his mother, who felt that warfare was "rather wicked", but she did not overrule his decision. While speaking of himself in 1948, Eisenhower said he was "one of the most deeply religious men I know" though unattached to any "sect or organization". He was baptized in the

Presbyterian Church

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

in 1953.

Eisenhower attended

Abilene High School and graduated with the class of 1909.

As a freshman, he injured his knee and developed a leg infection that extended into his groin, which his doctor diagnosed as life-threatening. The doctor insisted that the leg be amputated but Dwight refused to allow it, and surprisingly recovered, though he had to repeat his freshman year. He and brother

Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Eadgar'' (composed of '' ead'' "rich, prosperous" and '' gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the later medieval period; it was, however, r ...

both wanted to attend college, though they lacked the funds. They made a pact to take alternate years at college while the other worked to earn the tuitions.

Edgar took the first turn at school, and Dwight was employed as a night supervisor at the Belle Springs Creamery. When Edgar asked for a second year, Dwight consented and worked for a second year. At that time, a friend

Edward "Swede" Hazlett was applying to the

Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

See also

* Military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally pr ...

and urged Dwight to apply to the school, since no tuition was required. Eisenhower requested consideration for either Annapolis or West Point with his U.S. Senator,

Joseph L. Bristow

Joseph Little Bristow (July 22, 1861July 14, 1944) was a Republican Party (United States), Republican politician from the American state of Kansas. Elected in 1908, Bristow served a single term in the United States Senate where he gained recognit ...

. Though Eisenhower was among the winners of the entrance-exam competition, he was beyond the age limit for the Naval Academy.

He then accepted an appointment to West Point in 1911.

At West Point, Eisenhower relished the emphasis on traditions and on sports, but was less enthusiastic about the hazing, though he willingly accepted it as a plebe. He was also a regular violator of the more detailed regulations and finished school with a less than stellar discipline rating. Academically, Eisenhower's best subject by far was English. Otherwise, his performance was average, though he thoroughly enjoyed the typical emphasis of engineering on science and mathematics.

In athletics, Eisenhower later said that "not making the baseball team at West Point was one of the greatest disappointments of my life, maybe my greatest".

He made the

varsity football team and was a starter at

halfback in 1912, when he tried to tackle the legendary

Jim Thorpe

James Francis Thorpe ( Sac and Fox (Sauk): ''Wa-Tho-Huk'', translated as "Bright Path"; May 22 or 28, 1887March 28, 1953) was an American athlete and Olympic gold medalist. A member of the Sac and Fox Nation, Thorpe was the first Native ...

of the

Carlisle Indians. Eisenhower suffered a torn knee while being tackled in the next game, which was the last he played; he reinjured his knee on horseback and in the boxing ring,

[Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1967). ''At Ease: Stories I Tell to Friends'', Garden City, New York, Doubleday & Company, Inc.] so he turned to fencing and gymnastics.

Eisenhower later served as junior varsity football coach and cheerleader, which caught the attention of General

Frederick Funston

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a general in the United States Army, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War. He received ...

.

He graduated from West Point in the middle of the class of 1915, which became known as "

the class the stars fell on

"The class the stars fell on" is an expression used to describe the class of 1915 at the United States Military Academy in West Point, New York. In the United States Army, the insignia reserved for generals is one or more stars. Of the 164 gradu ...

", because 59 members eventually became

general officer

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED ...

s. After graduation in 1915, Second Lieutenant Eisenhower requested an assignment in the Philippines, which was denied; because of the ongoing

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution ( es, Revolución Mexicana) was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from approximately 1910 to 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It resulted in the destruction ...

, he was instead posted to

Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

in

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

, Texas, under the command of General Funston. In 1916, while stationed at Fort Sam Houston, Eisenhower was convinced by Funston to become the football coach for

Peacock Military Academy

The Peacock Military Academy was a college-preparatory school in San Antonio, Texas.

It was founded in 1894 by Dr. Wesley Peacock, Sr., who envisioned "the most thorough military school west of the Mississippi, governed by the honor system, and c ...

,

and later became the coach at St. Louis College, now

St. Mary's University; Eisenhower was an honorary member of the Sigma Beta Chi fraternity at St. Mary's University.

Personal life

While Eisenhower was stationed in Texas, he met

Mamie Doud

Mary Geneva "Mamie" Eisenhower (; November 14, 1896 – November 1, 1979) was the first lady of the United States from 1953 to 1961 as the wife of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Born in Boone, Iowa, she was raised in a wealthy household in ...

of

Boone, Iowa

Boone ( ) is a city in Des Moines Township, and county seat of Boone County, Iowa, United States.

It is the principal city of the Boone, Iowa Micropolitan Statistical Area, which encompasses all of Boone County. This micropolitan statistical ...

. They were immediately taken with each other. He proposed to her on

Valentine's Day

Valentine's Day, also called Saint Valentine's Day or the Feast of Saint Valentine, is celebrated annually on February 14. It originated as a Christian feast day honoring one or two early Christian martyrs named Saint Valentine and, thr ...

in 1916. A November wedding date in Denver was moved up to July 1 due to the impending

U.S. entry into World War I; Funston approved 10 days of leave for their wedding. The Eisenhowers moved many times during their first 35 years of marriage.

The Eisenhowers had two sons. In late 1917 while he was in charge of training at

Fort Oglethorpe in

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, his wife Mamie had their first son, Doud Dwight "Icky" Eisenhower (1917–1921), who died of

scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by '' Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects chi ...

at the age of three. Eisenhower was mostly reluctant to discuss his death. Their second son,

John Eisenhower

John Sheldon Doud Eisenhower (August 3, 1922 – December 21, 2013) was a United States Army officer, diplomat, and military historian. He was a son of President Dwight D. Eisenhower and First Lady Mamie Eisenhower. His military career sp ...

(1922–2013), was born in

Denver, Colorado

Denver () is a consolidated city and county, the capital, and most populous city of the U.S. state of Colorado. Its population was 715,522 at the 2020 census, a 19.22% increase since 2010. It is the 19th-most populous city in the Unit ...

. John served in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

, retired as a brigadier general, became an author and served as

U.S. Ambassador to Belgium

In 1832, shortly after the creation of the Kingdom of Belgium, the United States established diplomatic relations. Since that time, a long line of distinguished envoys have represented American interests in Belgium. These diplomats included men ...

from 1969 to 1971. Coincidentally, John graduated from

West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

on D-Day, June 6, 1944. He married Barbara Jean Thompson on June 10, 1947. John and Barbara had four children:

David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, Barbara Ann,

Susan Elaine and

Mary Jean. David, after whom

Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwest ...

is named, married

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

's daughter

Julie

Julie may refer to:

* Julie (given name), a list of people and fictional characters with the name

Film and television

* ''Julie'' (1956 film), an American film noir starring Doris Day

* ''Julie'' (1975 film), a Hindi film by K. S. Sethumadhav ...

in 1968.

Eisenhower was a golf enthusiast later in life, and he joined the

Augusta National Golf Club

Augusta National Golf Club, sometimes referred to as Augusta or the National, is a golf club in Augusta, Georgia, United States. Unlike most private clubs which operate as non-profits, Augusta National is a for-profit corporation, and it does ...

in 1948. He played golf frequently during and after his presidency and was unreserved in expressing his passion for the game, to the point of golfing during winter; he ordered his golf balls painted black so he could see them better against snow on the ground. He had a small, basic golf facility installed at

Camp David

Camp David is the country retreat for the president of the United States of America. It is located in the wooded hills of Catoctin Mountain Park, in Frederick County, Maryland, near the towns of Thurmont and Emmitsburg, about north-northwest ...

, and he became close friends with the Augusta National Chairman

Clifford Roberts, inviting Roberts to stay at the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

on numerous occasions. Roberts, an investment broker, also handled the Eisenhower family's investments.

Oil painting

Oil painting is the process of painting with pigments with a medium of drying oil as the binder. It has been the most common technique for artistic painting on wood panel or canvas for several centuries, spreading from Europe to the rest ...

was one of Eisenhower's hobbies. He began painting while at Columbia University, after watching

Thomas E. Stephens paint Mamie's portrait. In order to relax, Eisenhower painted about 260 oils during the last 20 years of his life. The images were mostly landscapes but also portraits of subjects such as Mamie, their grandchildren, General Montgomery,

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, and

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

.

stated that Eisenhower's paintings, "simple and earnest," caused her to "wonder at the hidden depths of this reticent president". A conservative in both art and politics, Eisenhower in a 1962 speech denounced modern art as "a piece of canvas that looks like a broken-down

Tin Lizzie

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relati ...

, loaded with paint, has been driven over it".

''

Angels in the Outfield'' was Eisenhower's favorite movie. His favorite reading material for relaxation were the Western novels of

Zane Grey

Pearl Zane Grey (January 31, 1872 – October 23, 1939) was an American author and dentist. He is known for his popular adventure novels and stories associated with the Western genre in literature and the arts; he idealized the American fronti ...

.

With his excellent memory and ability to focus, Eisenhower was skilled at card games. He learned poker, which he called his "favorite indoor sport", in Abilene. Eisenhower recorded West Point classmates' poker losses for payment after graduation and later stopped playing because his opponents resented having to pay him. A friend reported that after learning to play

contract bridge

Contract bridge, or simply bridge, is a trick-taking card game using a standard 52-card deck. In its basic format, it is played by four players in two competing partnerships, with partners sitting opposite each other around a table. Millions ...

at West Point, Eisenhower played the game six nights a week for five months.

Eisenhower continued to play bridge throughout his military career. While stationed in the Philippines, he played regularly with President

Manuel Quezon

Manuel Luis Quezon y Molina, (; 19 August 1878 – 1 August 1944), also known by his initials MLQ, was a Filipino lawyer, statesman, soldier and politician who served as president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines from 1935 until his d ...

, earning him the nickname the "Bridge Wizard of Manila".

During WWII, an unwritten qualification for an officer's appointment to Eisenhower's staff was the ability to play a sound game of bridge. He played even during the stressful weeks leading up to the D-Day landings. His favorite partner was General

Alfred Gruenther

General Alfred Maximilian Gruenther (March 3, 1899 – May 30, 1983) was a senior United States Army officer, Red Cross president, and bridge player. After being commissioned towards the end of World War I, he served in the army throughout t ...

, considered the best player in the U.S. Army; he appointed Gruenther his second-in-command at NATO partly because of his skill at bridge. Saturday night bridge games at the White House were a feature of his presidency. He was a strong player, though not an expert by modern standards. The great bridge player and popularizer

Ely Culbertson

Elie Almon Culbertson (July 22, 1891 – December 27, 1955), known as Ely Culbertson, was an American contract bridge entrepreneur and personality dominant during the 1930s. He played a major role in the popularization of the new game and was wide ...

described his game as classic and sound with "flashes of brilliance" and said that "you can always judge a man's character by the way he plays cards. Eisenhower is a calm and collected player and never whines at his losses. He is brilliant in victory but never commits the bridge player's worst crime of gloating when he wins." Bridge expert

Oswald Jacoby frequently participated in the White House games and said, "The President plays better bridge than golf. He tries to break 90 at golf. At bridge, you would say he plays in the 70s."

World War I (1914–1918)

Eisenhower served initially in logistics and then the

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and mar ...

at various camps in Texas and

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

until 1918. When the U.S. entered

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, he immediately requested an overseas assignment but was again denied and then assigned to

Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. In February 1918, he was transferred to

Camp Meade

Camp George G. Meade near Middletown, Pennsylvania, was a camp established and subsequently abandoned by the U.S. Volunteers during the Spanish–American War.

History

Camp Meade was established August 24, 1898, and soon thereafter was occupie ...

in

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

with the

65th Engineers. His unit was later ordered to France, but, to his chagrin, he received orders for the new

tank corps, where he was promoted to brevet

lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

in the

National Army. He commanded a unit that trained tank crews at

Camp Colt

Camp may refer to:

Outdoor accommodation and recreation

* Campsite or campground, a recreational outdoor sleeping and eating site

* a temporary settlement for nomads

* Camp, a term used in New England, Northern Ontario and New Brunswick to descri ...

– his first command – at the site of "

Pickett's Charge

Pickett's Charge (July 3, 1863), also known as the Pickett–Pettigrew–Trimble Charge, was an infantry assault ordered by Confederate General Robert E. Lee against Major General George G. Meade's Union positions on the last day of the ...

" on the

Gettysburg Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

battleground. Though Eisenhower and his tank crews never saw combat, he displayed excellent organizational skills as well as an ability to accurately assess junior officers' strengths and make optimal placements of personnel.

Once again his spirits were raised when the unit under his command received orders overseas to France. This time his wishes were thwarted when the

armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

was signed a week before his departure date. Completely missing out on the warfront left him depressed and bitter for a time, despite receiving the

Distinguished Service Medal Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a high award of a nation.

Examples include:

*Distinguished Service Medal (Australia) (established 1991), awarded to personnel of the Australian Defence Force for distinguished leadership in action

* Distinguishe ...

for his work at home. In World War II, rivals who had combat service in the Great War (led by Gen.

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence an ...

) sought to denigrate Eisenhower for his previous lack of combat duty, despite his stateside experience establishing a camp, completely equipped, for thousands of troops and developing a full combat training schedule.

In service of generals

After the war, Eisenhower reverted to his regular rank of

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

and a few days later was promoted to

major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

, a rank he held for 16 years.

The major was assigned in 1919 to a

transcontinental Army convoy to test vehicles and dramatize the need for improved roads in the nation. Indeed, the convoy averaged only from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco; later the improvement of highways became a signature issue for Eisenhower as president.

He assumed duties again at

Camp Meade

Camp George G. Meade near Middletown, Pennsylvania, was a camp established and subsequently abandoned by the U.S. Volunteers during the Spanish–American War.

History

Camp Meade was established August 24, 1898, and soon thereafter was occupie ...

,

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

, commanding a battalion of tanks, where he remained until 1922. His schooling continued, focused on the nature of the next war and the role of the tank in it. His new expertise in

tank warfare was strengthened by a close collaboration with

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

,

Sereno E. Brett

Sereno Elmer Brett (October 31, 1891 – September 9, 1952) was a highly decorated brigadier general in the United States Army who fought in both World War I and World War II and played a key, if little recognized today, role in the develop ...

, and other senior tank leaders. Their leading-edge ideas of speed-oriented offensive tank warfare were strongly discouraged by superiors, who considered the new approach too radical and preferred to continue using tanks in a strictly supportive role for the infantry. Eisenhower was even threatened with

court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

for continued publication of these proposed methods of tank deployment, and he relented.

From 1920, Eisenhower served under a succession of talented generals –

Fox Conner

Fox Conner (November 2, 1874 – October 13, 1951) was a Major general (United States), major general of the United States Army. He served as operations officer for the American Expeditionary Force during World War I, and is best remembered as a ...

,

John J. Pershing,

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

and

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

. He first became executive officer to General Conner in the

Panama Canal Zone

The Panama Canal Zone ( es, Zona del Canal de Panamá), also simply known as the Canal Zone, was an unincorporated territory of the United States, located in the Isthmus of Panama, that existed from 1903 to 1979. It was located within the ter ...

, where, joined by Mamie, he served until 1924. Under Conner's tutelage, he studied military history and theory (including

Carl von Clausewitz

Carl Philipp Gottfried (or Gottlieb) von Clausewitz (; 1 June 1780 – 16 November 1831) was a Prussian general and military theorist who stressed the "moral", in modern terms meaning psychological, and political aspects of waging war. His mo ...

's ''

On War

''Vom Kriege'' () is a book on war and military strategy by Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831), written mostly after the Napoleonic wars, between 1816 and 1830, and published posthumously by his wife Marie von Brühl in 1832. ...

''), and later cited Conner's enormous influence on his military thinking, saying in 1962 that "Fox Conner was the ablest man I ever knew." Conner's comment on Eisenhower was, "

eis one of the most capable, efficient and loyal officers I have ever met." On Conner's recommendation, in 1925–26 he attended the

Command and General Staff College

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Kansas, where he graduated first in a class of 245 officers. He then served as a

battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions ...

commander at

Fort Benning

Fort Benning is a United States Army post near Columbus, Georgia, adjacent to the Alabama– Georgia border. Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve component soldiers, retirees and civilian employee ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, until 1927.

During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Eisenhower's career in the post-war army stalled somewhat, as military priorities diminished; many of his friends resigned for high-paying business jobs. He was assigned to the

American Battle Monuments Commission

The American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) is an independent agency of the United States government that administers, operates, and maintains permanent U.S. military cemeteries, memorials and monuments primarily outside the United States.

...

directed by General Pershing, and with the help of his brother

Milton Eisenhower

Milton Stover Eisenhower (September 15, 1899 – May 2, 1985) was an American academic administrator. He served as president of three major American universities: Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Johns Hopkins Universit ...

, then a journalist at the

U.S. Agriculture Department, he produced a guide to American battlefields in Europe. He then was assigned to the

Army War College and graduated in 1928. After a one-year assignment in France, Eisenhower served as executive officer to General

George V. Moseley,

Assistant Secretary of War

The United States Assistant Secretary of War was the second–ranking official within the American Department of War from 1861 to 1867, from 1882 to 1883, and from 1890 to 1940. According to thMilitary Laws of the United States "The act of August 5 ...

, from 1929 to February 1933. Major Dwight D. Eisenhower graduated from the

Army Industrial College

The Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy (Eisenhower School), formerly known as the Industrial College of the Armed Forces (ICAF), is a part of the National Defense University. It was renamed on September 6, 20 ...

(Washington, DC) in 1933 and later served on the faculty (it was later expanded to become the Industrial College of the Armed Services and is now known as the

Dwight D. Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy).

His primary duty was planning for the next war, which proved most difficult in the midst of the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. He then was posted as chief military aide to General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was ...

,

Army Chief of Staff. In 1932, he participated in the clearing of the

Bonus March

The Bonus Army was a group of 43,000 demonstrators – 17,000 veterans of U.S. involvement in World War I, their families, and affiliated groups – who gathered in Washington, D.C., in mid-1932 to demand early cash redemption of their servi ...

encampment in Washington, D.C. Although he was against the actions taken against the veterans and strongly advised MacArthur against taking a public role in it, he later wrote the Army's official incident report, endorsing MacArthur's conduct.

In 1935, he accompanied MacArthur to

the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, where he served as assistant military adviser to the

Philippine government

The Government of the Philippines ( fil, Pamahalaan ng Pilipinas) has three interdependent branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. The Philippines is governed as a unitary state under a presidential representative and d ...

in developing their army. Eisenhower had strong philosophical disagreements with MacArthur regarding the role of the

Philippine Army

The Philippine Army (PA) (Tagalog: ''Hukbong Katihan ng Pilipinas''; in literal English: ''Army of the Ground of the Philippines''; in literal Spanish: ''Ejército de la Tierra de la Filipinas'') is the main, oldest and largest branch of the ...

and the leadership qualities that an American army officer should exhibit and develop in his subordinates. The resulting antipathy between Eisenhower and MacArthur lasted the rest of their lives.

Historians have concluded that this assignment provided valuable preparation for handling the challenging personalities of

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from ...

,

George S. Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France ...

,

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Chief of Staff of the US Army under Pre ...

, and

Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence an ...

during World War II. Eisenhower later emphasized that too much had been made of the disagreements with MacArthur and that a positive relationship endured. While in Manila, Mamie suffered a life-threatening stomach ailment but recovered fully. Eisenhower was promoted to the rank of permanent lieutenant colonel in 1936. He also learned to fly, making a solo flight over the Philippines in 1937, and obtained his private pilot's license in 1939 at

Fort Lewis. Also around this time, he was offered a post by the

Philippine Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of the Philippines ( es, Commonwealth de Filipinas or ; tl, Komonwelt ng Pilipinas) was the administrative body that governed the Philippines from 1935 to 1946, aside from a period of exile in the Second World War from 1942 ...

Government, namely by then Philippine President

Manuel L. Quezon on recommendations by MacArthur, to become the chief of police of a new capital being planned, now named

Quezon City

Quezon City (, ; fil, Lungsod Quezon ), also known as the City of Quezon and Q.C. (read in Filipino as Kyusi), is the List of cities in the Philippines, most populous city in the Philippines. According to the 2020 census, it has a populatio ...

, but he declined the offer.

Eisenhower returned to the United States in December 1939 and was assigned as

commanding officer

The commanding officer (CO) or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually given wide latitu ...

(CO) of the 1st Battalion,

15th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Lewis, Washington, later becoming the regimental

executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

. In March 1941 he was promoted to colonel and assigned as chief of staff of the newly activated

IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German ...

under Major General

Kenyon Joyce

Kenyon A. Joyce was a major general in the United States Army. He commanded the 1st Cavalry Division and later IX Corps in World War II.

Joyce was a prominent cavalry officer in the early outset of the war and was a mentor to a young George S. ...

. In June 1941, he was appointed chief of staff to General

Walter Krueger

Walter Krueger (26 January 1881 – 20 August 1967) was an American soldier and general officer in the first half of the 20th century. He commanded the Sixth United States Army in the South West Pacific Area during World War II. He rose fr ...

, Commander of the

Third Army, at

Fort Sam Houston

Fort Sam Houston is a U.S. Army post in San Antonio, Texas.

"Fort Sam Houston, TX • About Fort Sam Houston" (overview),

US Army, 2007, webpageSH-Army.

Known colloquially as "Fort Sam," it is named for the U.S. Senator from Texas, U.S. Represen ...

in

San Antonio

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_ ...

,

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. After successfully participating in the

Louisiana Maneuvers

The Louisiana Maneuvers were a series of major U.S. Army exercises held in 1941 in northern and west-central Louisiana, an area bounded by the Sabine River to the west, the Calcasieu River to the east, and by the city of Shreveport to the nort ...

, he was promoted to

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointe ...

on October 3, 1941. Although his administrative abilities had been noticed, on the eve of the American entry into

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

he had never held an active command above a battalion and was far from being considered by many as a potential commander of major operations.

World War II (1939–1945)

After the

Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower was assigned to the General Staff in

Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, where he served until June 1942 with responsibility for creating the major war plans to defeat

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

and

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. He was appointed Deputy Chief in charge of Pacific Defenses under the Chief of War Plans Division (WPD), General

Leonard T. Gerow, and then succeeded Gerow as Chief of the War Plans Division. Next, he was appointed Assistant Chief of Staff in charge of the new Operations Division (which replaced WPD) under Chief of Staff General

George C. Marshall, who spotted talent and promoted accordingly.

At the end of May 1942, Eisenhower accompanied Lt. Gen.

Henry H. Arnold, commanding general of the

Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

, to

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

to assess the effectiveness of the theater commander in

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, Maj. Gen.

James E. Chaney

James Eucene Chaney (March 16, 1885 – August 21, 1967) was a senior United States Army officer. He served in both World War I and World War II.

Early life

James Eucene Chaney was born in Chaneyville, Maryland. He studied at public schools ...

. He returned to Washington on June 3 with a pessimistic assessment, stating he had an "uneasy feeling" about Chaney and his staff. On June 23, 1942, he returned to London as Commanding General,

European Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground For ...

(ETOUSA), based in London and with a house on

Coombe, Kingston upon Thames

Coombe is a historic neighbourhood in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames in south west London, England. It sits on high ground, east of Norbiton. Most of the area was part of the former Municipal Borough of Malden and Coombe before local ...

, and took over command of ETOUSA from Chaney.

He was promoted to lieutenant general on July 7.

Operations Torch and Avalanche

In November 1942, Eisenhower was also appointed

Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force of the

North African Theater of Operations

The Mediterranean Theater of Operations, United States Army (MTOUSA), originally called the North African Theater of Operations, United States Army (NATOUSA), was a military formation of the United States Army that supervised all U.S. Army fo ...

(NATOUSA) through the new operational Headquarters

Allied (Expeditionary) Force Headquarters (A(E)FHQ). The word "expeditionary" was dropped soon after his appointment for security reasons. The campaign in North Africa was designated

Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while al ...

and was planned

in the underground headquarters within the

Rock of Gibraltar

The Rock of Gibraltar (from the Arabic name Jabel-al-Tariq) is a monolithic limestone promontory located in the British territory of Gibraltar, near the southwestern tip of Europe on the Iberian Peninsula, and near the entrance to the Medite ...

. Eisenhower was the first non-British person to command

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

in 200 years.

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

cooperation was deemed necessary to the campaign and Eisenhower encountered a "preposterous situation" with the multiple rival factions in France. His primary objective was to move forces successfully into

Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and intending to facilitate that objective, he gave his support to

François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his service ...

as High Commissioner in North Africa, despite Darlan's previous high offices of state in

Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

and his continued role as commander-in-chief of the

French armed forces

The French Armed Forces (french: Forces armées françaises) encompass the Army, the Navy, the Air and Space Force and the Gendarmerie of the French Republic. The President of France heads the armed forces as Chief of the Armed Forces.

France ...

. The

Allied leaders were "thunderstruck" by this from a political standpoint, though none of them had offered Eisenhower guidance with the problem in the course of planning the operation. Eisenhower was severely criticized for the move. Darlan was assassinated on December 24 by

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle

Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle (4 November 1922 – 26 December 1942) was a royalist member of the French resistance during World War II. He assassinated Admiral of the Fleet François Darlan, the former chief of government of Vichy France and th ...

, a French antifascist monarchist. Eisenhower later appointed, as High Commissioner, General

Henri Giraud

Henri Honoré Giraud (18 January 1879 – 11 March 1949) was a French general and a leader of the Free French Forces during the Second World War until he was forced to retire in 1944.

Born to an Alsatian family in Paris, Giraud graduated from ...

, who had been installed by the Allies as Darlan's commander-in-chief.

Operation Torch also served as a valuable training ground for Eisenhower's combat command skills; during the initial phase of ''

Generalfeldmarschall

''Generalfeldmarschall'' (from Old High German ''marahscalc'', "marshal, stable master, groom"; en, general field marshal, field marshal general, or field marshal; ; often abbreviated to ''Feldmarschall'') was a rank in the armies of several ...

''

Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

's move into the

Kasserine Pass

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a series of battles of the Tunisian campaign of World War II that took place in February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia.

The Axis forces, ...

, Eisenhower created some confusion in the ranks by some interference with the execution of battle plans by his subordinates. He also was initially indecisive in his removal of

Lloyd Fredendall

Lieutenant General Lloyd Ralston Fredendall (December 28, 1883 – October 4, 1963) was a senior officer of the United States Army who served during World War II. He is best known for his leadership failure during the Battle of Kasserine Pass ...

, commanding

U.S. II Corps. He became more adroit in such matters in later campaigns. In February 1943, his authority was extended as commander of AFHQ across the

Mediterranean basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

to include the

British Eighth Army

The Eighth Army was an Allied field army formation of the British Army during the Second World War, fighting in the North African and Italian campaigns. Units came from Australia, British India, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Free French Force ...

, commanded by

General

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". O ...

Sir Bernard Montgomery. The Eighth Army had

advanced across the Western Desert from the east and was ready for the start of the

Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the Second World War, between Axis and Allied forces from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943. Th ...

. Eisenhower gained his

fourth star and gave up command of ETOUSA to become commander of NATOUSA.

After the capitulation of

Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

forces in North Africa, Eisenhower oversaw the

invasion of Sicily

The Allied invasion of Sicily, also known as Operation Husky, was a major campaign of World War II in which the Allied forces invaded the island of Sicily in July 1943 and took it from the Axis powers ( Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany). It bega ...

. Once

Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until Fall of the Fascist re ...

, the

Italian leader, had fallen in

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the Allies switched their attention to the mainland with

Operation Avalanche. But while Eisenhower argued with

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

and

British Prime Minister

The prime minister of the United Kingdom is the head of government of the United Kingdom. The prime minister advises the sovereign on the exercise of much of the royal prerogative, chairs the Cabinet and selects its ministers. As moder ...

Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

, who both insisted on unconditional terms of surrender in exchange for helping the

Italians

, flag =

, flag_caption = The national flag of Italy

, population =

, regions = Italy 55,551,000

, region1 = Brazil

, pop1 = 25–33 million

, ref1 =

, region2 ...

, the Germans pursued an aggressive buildup of forces in the country. The Germans made the already tough battle more difficult by adding 19

divisions and initially outnumbering the

Allied forces 2 to 1.

Supreme Allied commander and Operation Overlord

In December 1943, President Roosevelt decided that Eisenhower – not Marshall – would be Supreme Allied Commander in

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

. The following month, he resumed command of ETOUSA and the following month was officially designated as the