Dublin Lock-out on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Dublin lock-out was a major

Among the employers in Ireland opposed to trade unions such as Larkin's ITGWU was William Martin Murphy, Ireland's most prominent capitalist, born in Castletownbere, County Cork. In 1913, Murphy was chairman of the

Among the employers in Ireland opposed to trade unions such as Larkin's ITGWU was William Martin Murphy, Ireland's most prominent capitalist, born in Castletownbere, County Cork. In 1913, Murphy was chairman of the

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in the

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in the

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914, when the TUC in Britain rejected Larkin and Connolly's request for a sympathetic strike. Most workers, many of whom were on the brink of starvation, went back to work and signed pledges not to join the ITGWU. It was badly damaged by its defeat in the Lockout and was further hit by the departure of Larkin to the United States in 1914 and the execution of Connolly, one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916.

The union was rebuilt by

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914, when the TUC in Britain rejected Larkin and Connolly's request for a sympathetic strike. Most workers, many of whom were on the brink of starvation, went back to work and signed pledges not to join the ITGWU. It was badly damaged by its defeat in the Lockout and was further hit by the departure of Larkin to the United States in 1914 and the execution of Connolly, one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916.

The union was rebuilt by

Postcolonial Yeats: Culture, Enlightenment, and the Public Sphere

, ''Field Day Review'', Volume 2 (2008), p. 67 and footnote In the poem, Yeats wrote mockingly of commerciants who "fumble in a greasy till, and add the halfpence to the pence" and asked:

Was it for this the wild geese spread

The grey wing upon every tide;

For this that all that blood was shed,

For this Edward Fitzgerald died,

And Robert Emmet and Wolfe Tone,

All that delirium of the brave?

Romantic Ireland's dead and gone,

It's with O'Leary in the grave.

Padraig Yeates, ''The Dublin 1913 Lockout'', History Ireland, 2001.

* Dublin Disturbances Commission (HMSO 1914) *

''Report''

''Minutes of Evidence and Appendices''

The Irish Story archive on the Lockout

Retrieved 2013-07-09 * * *

Church opposition to sending children to England * * * {{Authority control History of Ireland (1801–1923) 1913 labor disputes and strikes 1914 labor disputes and strikes History of County Dublin Labour disputes in Ireland Labour disputes in the United Kingdom 1913 in Ireland 1914 in Ireland

industrial dispute

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the I ...

between approximately 20,000 workers and 300 employers that took place in Ireland's capital and largest city, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

. The dispute, lasting from 26 August 1913 to 18 January 1914, is often viewed as the most severe and significant industrial dispute in Irish history. Central to the dispute was the workers' right to unionise

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical th ...

.

Background

Poverty and housing

Many of Dublin's workers lived in terrible conditions intenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, i ...

s. For example, over 830 people lived in just 15 houses in Henrietta Street's Georgian tenements. At 10 Henrietta Street, the Irish Sisters of Charity The Religious Sisters of Charity or Irish Sisters of Charity is a Roman Catholic religious institute founded by Mary Aikenhead in Ireland on 15 January 1815. Its motto is ('The love Christ urges us on'; ).

The institute has its headquarters in D ...

ran a laundry that was inhabited by more than 50 single women. An estimated four million pledges were taken in pawnbrokers every year. The infant mortality rate among the poor was 142 per 1,000 births, extraordinarily high for a European city. The situation was made considerably worse by the high rate of disease in the slums, which was worsened by the lack of health care and cramped living conditions. The most prevalent disease in the Dublin slums at the time was tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in w ...

(TB), which spread through tenements very quickly and caused many deaths in the poor. A report, published in 1912, found that TB-related deaths in Ireland were 50% higher than in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

or Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

. The vast majority of TB-related deaths in Ireland occurred among the poorer classes. The report updated a 1903 study by Dr John Lumsden.

Poverty was perpetuated in Dublin by the lack of work for unskilled workers, who did not have any form of representation before trade unions were founded. The unskilled workers often had to compete with one another for work every day, with the job generally going to whoever agreed to work for the lowest wages.

James Larkin and formation of ITGWU

James Larkin

James Larkin (28 January 1874 – 30 January 1947), sometimes known as Jim Larkin or Big Jim, was an Irish republicanism, Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. He was one of the founders of the Irish Labour Party (Ireland), Labou ...

, the main protagonist on the side of the workers in the dispute, was a docker in Liverpool

Liverpool is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the List of English districts by population, 10th largest English district by population and its E ...

and a union organiser. In 1907, he was sent to Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingd ...

as a local organiser of the British-based National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL). In Belfast, Larkin organised a strike of dock and transport workers. It was also in Belfast that Larkin began to use the tactic of the sympathetic strike

Solidarity action (also known as secondary action, a secondary boycott, a solidarity strike, or a sympathy strike) is industrial action by a trade union in support of a strike initiated by workers in a separate corporation, but often the same en ...

in which workers who were not directly involved in an industrial dispute with employers would go on strike in support of other workers, who were striking. The Belfast strike was moderately successful and boosted Larkin's standing among Irish workers. However, his tactics were highly controversial and so Larkin was transferred to Dublin.

Unskilled workers in Dublin were very much at the mercy of their employers. Employers who suspected workers of trying to organise themselves could blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, ...

them to destroy them any chance of future employment. Larkin set about organising the unskilled workers of Dublin, which was a cause of concern for the NUDL, which was reluctant to engage in a full-scale industrial dispute with the powerful Dublin employers. It suspended Larkin from the NUDL in 1908. Larkin then left the NUDL and set up an Irish union, the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union

The Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU), was a trade union representing workers, initially mainly labourers, in Ireland.

History

The union was founded by James Larkin in January 1909 as a general union. Initially drawing its ...

(ITGWU).

The ITGWU was the first Irish trade union to cater for both skilled and unskilled workers. In its first few months, it quickly gained popularity and soon spread to other Irish cities. The ITGWU was used as a vehicle for Larkin's syndicalist

Syndicalism is a revolutionary current within the left-wing of the labor movement that seeks to unionize workers according to industry and advance their demands through strikes with the eventual goal of gaining control over the means of pro ...

views. He believed in bringing about a socialist revolution

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

by the establishment of trade unions and calling general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

s.

The ITGWU initially lost several strikes between 1908 and 1910 but after 1913 won strikes involving carters and railway workers like the 1913 Sligo dock strike. Between 1911 and 1913, membership of the ITGWU rose from 4,000 to 10,000, to the alarm of employers.

Larkin had learned from the methods of the 1910 Tonypandy riots and the 1911 Liverpool general transport strike

The 1911 Liverpool general transport strike, also known as the great transport workers' strike, involved dockers, railway workers, sailors and other tradesmen. The strike paralysed Liverpool commerce for most of the summer of 1911. It also transf ...

.

Larkin, Connolly and Irish Labour Party

Another important figure in the rise of an organised workers' movement in Ireland at the time wasJames Connolly

James Connolly ( ga, Séamas Ó Conghaile; 5 June 1868 – 12 May 1916) was an Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader. Born to Irish parents in the Cowgate area of Edinburgh, Scotland, Connolly left school for working life at the ...

, an Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

-born Marxist of Irish parentage. Connolly was a talented orator and a fine writer. He became known for his speeches on the streets of Dublin in support of socialism and Irish nationalism. In 1896, Connolly established the Irish Socialist Republican Party

The Irish Socialist Republican Party was a small, but pivotal Irish political party founded in 1896 by James Connolly. Its aim was to establish an Irish workers' republic. The party split in 1904 following months of internal political rows.

Hi ...

and the newspaper ''The Workers' Republic''. In 1911, Connolly was appointed the ITGWU's Belfast organiser. In 1912, Connolly and Larkin formed the Irish Labour Party to represent workers in the imminent Home Rule Bill

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1870 to the e ...

debate in the British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the Parliamentary sovereignty in the United Kingdom, supreme Legislature, legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of We ...

. Home rule, although passed in the House of Commons, was postponed, by the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

. The plan was then suspended for one year, then indefinitely, after the rise of militant nationalism after the 1916 Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

.

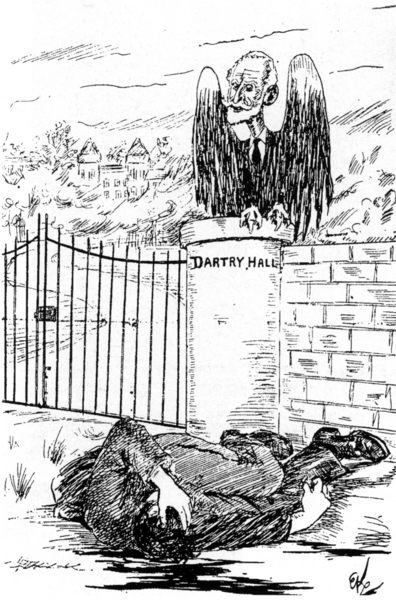

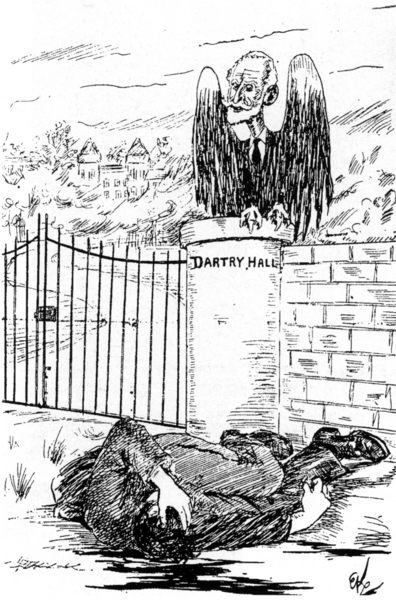

William Martin Murphy and employers

Among the employers in Ireland opposed to trade unions such as Larkin's ITGWU was William Martin Murphy, Ireland's most prominent capitalist, born in Castletownbere, County Cork. In 1913, Murphy was chairman of the

Among the employers in Ireland opposed to trade unions such as Larkin's ITGWU was William Martin Murphy, Ireland's most prominent capitalist, born in Castletownbere, County Cork. In 1913, Murphy was chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company

The Dublin United Transport Company (DUTC) operated trams and buses in Dublin, Ireland until 1945. Following legislation in the Oireachtas, the ''Transport Act, 1944'', the DUTC and the Great Southern Railways were vested in the newly formed C ...

and owned Clery's department store and the Imperial Hotel. He controlled the ''Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper and online publication which is owned by Independent News & Media (INM), a subsidiary of Mediahuis.

The newspaper version often includes glossy magazines.

Traditionally a broadsheet n ...

'', ''Evening Herald

''The Herald'' is a nationwide mid-market tabloid newspaper headquartered in Dublin, Ireland, and published by Independent News & Media who are a subsidiary of Mediahuis. It is published Monday–Saturday. The newspaper was known as the ''Eve ...

'' and ''Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the Briti ...

'' newspapers and was a major shareholder in the B&I Line. Murphy was also a prominent Irish nationalist

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of ...

and a former Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

MP in Parliament.

Even today, his defenders insist that he was a charitable man and a good employer and that his workers received fair wages. However, conditions in his many enterprises were often poor or worse, with employees given only one day off in 10 and being forced to labour up to 17 hours a day. Dublin tramway workers were paid substantially less than their counterparts in Belfast and Liverpool and were subjected to a regime of punitive fines, probationary periods extending for as long as six years and a culture of company surveillance involving the widespread use of informers.

Murphy was not opposed in principle to trade unions, particularly craft unions, but he was vehemently opposed to the ITGWU and saw its leader, Larkin, as a dangerous revolutionary. In July 1913, Murphy presided over a meeting of 300 employers during which a collective response to the rise of trade unionism was agreed. Murphy and the employers were determined not to allow the ITGWU to unionise the Dublin workforce. On 15 August, Murphy dismissed 40 workers whom he suspected of ITGWU membership, followed by another 300 over the next week.

Dispute

Escalation

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in the

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in the history of Ireland

The first evidence of human presence in Ireland dates to around 33,000 years ago, with further findings dating the presence of homo sapiens to around 10,500 to 7,000 BC. The receding of the ice after the Younger Dryas cold phase of the Quatern ...

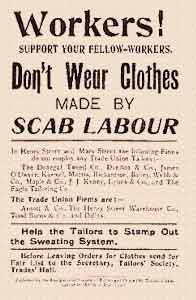

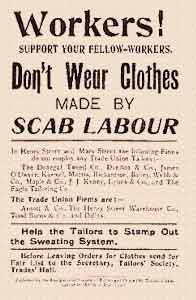

. Employers in Dublin locked out their workers and employed blackleg labour from Britain and elsewhere in Ireland. Dublin's workers, despite being some of the poorest in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the European mainland, continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

at the time, applied for help and were sent £150,000 by the British Trades Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions in England and Wales, representing the majority of trade unions. There are 48 affiliated unions, with a total of about 5.5 million members. Frances O ...

(TUC) and other sources in Ireland, doled out dutifully by the ITGWU.

The "Kiddies' Scheme" for the starving children of Irish strikers to be temporarily looked after by British trade unionists was blocked by the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and especially the Ancient Order of Hibernians

The Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH; ) is an Irish Catholic fraternal organization. Members must be male, Catholic, and either born in Ireland or of Irish descent. Its largest membership is now in the United States, where it was founded in ...

, which claimed that Catholic children would be subject to Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

or atheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

influences when in Britain. The Church supported the employers during the dispute and condemned Larkin as a socialist revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor. ...

.

Notably, Guinness

Guinness () is an Irish dry stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at St. James's Gate, Dublin, Ireland, in 1759. It is one of the most successful alcohol brands worldwide, brewed in almost 50 countries, and available in ...

, the largest employer and biggest exporter in Dublin, refused to lock out its workforce. It refused to join Murphy's group but sent £500 to the employers' fund. It had a policy against sympathetic strikes and expected its workers, whose conditions were far better than the norm in Ireland, not to strike in sympathy; six who had done so were dismissed. It had 400 of its staff who were already ITGWU members and so it had a working relationship with the union. Larkin appealed to have the six reinstated but without success.

Strikers used mass pickets and intimidation against strike-breakers, who were also violent towards strikers. The Dublin Metropolitan Police carried out a baton charge

A baton charge is a coordinated tactic for dispersing crowds of people, usually used by police or military in response to public disorder. In South Asia, a long bamboo stick, called ''lathi'' in Hindi, is used for crowd control, and the expressi ...

st worker's rallies. On 31 August 1913, the DMP attacked a meeting on Sackville Street (Noé O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections bisected by Henry ...

) that had been publicly banned. It caused the deaths of two workers: James Nolan and John Byrne. Over 300 more were injured.

The baton charge was a response to the appearance of James Larkin, who had been banned from holding a meeting, to speak for the workers. He had been smuggled into William Martin Murphy's Imperial Hotel by Nellie Gifford

Nellie Gifford (9 November 1880 – 23 June 1971) was an Irish republican activist and nationalist.

Early life

Born Helen Ruth Gifford on 9 November 1880 in Phibsborough, Dublin to Frederick Gifford (1835/6–1917), a solicitor, and Isabella ...

, the sister-in-law of Thomas MacDonagh

Thomas Stanislaus MacDonagh ( ga, Tomás Anéislis Mac Donnchadha; 1 February 1878 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish political activist, poet, playwright, educationalist and revolutionary leader. He was one of the seven leaders of the Easter Rising ...

, and spoke from a balcony. The event is remembered as Bloody Sunday, a term used for two subsequent days in 20th-century Ireland and for the murderous charge of police in the Liverpool general strike. Another worker, Alice Brady, was later shot dead by a strike-breaker as she brought home a food parcel from the union office. Michael Byrne, an ITGWU official from Kingstown

Kingstown is the capital, chief port, and main commercial centre of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. With a population of 12,909 (2012), Kingstown is the most populous settlement in the country. It is the island's agricultural industry centr ...

, died after he had been tortured in a police cell.

Connolly, Larkin and ex-British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Jack White formed a worker's militia, the Irish Citizen Army

The Irish Citizen Army (), or ICA, was a small paramilitary group of trained trade union volunteers from the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU) established in Dublin for the defence of workers' demonstrations from the Dublin ...

, to protect workers' demonstrations.

For seven months, the lock-out affected tens of thousands of Dublin families. Murphy's three main newspapers, the ''Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper and online publication which is owned by Independent News & Media (INM), a subsidiary of Mediahuis.

The newspaper version often includes glossy magazines.

Traditionally a broadsheet n ...

'', the '' Sunday Independent'' and the ''Evening Herald

''The Herald'' is a nationwide mid-market tabloid newspaper headquartered in Dublin, Ireland, and published by Independent News & Media who are a subsidiary of Mediahuis. It is published Monday–Saturday. The newspaper was known as the ''Eve ...

'', portrayed Larkin as the villain. Influential figures such as Patrick Pearse

Patrick Henry Pearse (also known as Pádraig or Pádraic Pearse; ga, Pádraig Anraí Mac Piarais; 10 November 1879 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish teacher, barrister, poet, writer, nationalist, republican political activist and revolutionary who ...

, Countess Markievicz and William Butler Yeats

William Butler Yeats (13 June 186528 January 1939) was an Irish poet, dramatist, writer and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. He was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival and became a pillar of the Irish liter ...

supported the workers in the media.

End

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914, when the TUC in Britain rejected Larkin and Connolly's request for a sympathetic strike. Most workers, many of whom were on the brink of starvation, went back to work and signed pledges not to join the ITGWU. It was badly damaged by its defeat in the Lockout and was further hit by the departure of Larkin to the United States in 1914 and the execution of Connolly, one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916.

The union was rebuilt by

The lock-out eventually concluded in early 1914, when the TUC in Britain rejected Larkin and Connolly's request for a sympathetic strike. Most workers, many of whom were on the brink of starvation, went back to work and signed pledges not to join the ITGWU. It was badly damaged by its defeat in the Lockout and was further hit by the departure of Larkin to the United States in 1914 and the execution of Connolly, one of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916.

The union was rebuilt by William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

and Thomas Johnson. By 1919, its membership had surpassed that of 1913.

Many of the blacklisted workers joined the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gur ...

since they had no other source of pay to support their families, and they found themselves in the trenches of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

within the year.

Although the actions of the ITGWU and the smaller UBLU had been unsuccessful in achieving substantially better pay and conditions for workers, they marked a watershed in Irish labour history. The principle of union action and workers' solidarity had been firmly established. No future employer would ever try to "break" a union as Murphy had attempted to with the ITGWU. The lock-out had damaged commercial businesses in Dublin, with many forced to declare bankruptcy.

W.B. Yeats' "September 1913"

''September 1913'', one of the most famous of W. B. Yeats' poems, was published in ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' during the lock-out. Although the occasion of the poem was the decision of Dublin Corporation not to build a gallery to house the Hugh Lane collection of paintings (William Martin Murphy was one of the most vocal opponents of the plan), it has sometimes been viewed by scholars as a commentary on the lock-out.Marjorie Howes,Postcolonial Yeats: Culture, Enlightenment, and the Public Sphere

, ''Field Day Review'', Volume 2 (2008), p. 67 and footnote In the poem, Yeats wrote mockingly of commerciants who "fumble in a greasy till, and add the halfpence to the pence" and asked:

See also

*Great Unrest

The Great Unrest, also known as the Great Labour Unrest, was a period of labour revolt between 1911 and 1914 in the United Kingdom. The agitation included the 1911 Liverpool general transport strike, the Tonypandy riots, the National coal strike ...

References

Bibliography

* Conor McNamara, Padraig Yeates, 'Dublin Lockout 1913, New Perspectives on Class War and its Legacy' (Irish Academic Press, 2017). * *Padraig Yeates, ''The Dublin 1913 Lockout'', History Ireland, 2001.

* Dublin Disturbances Commission (HMSO 1914) *

''Report''

d. 7269 D. or d. may refer to, usually as an abbreviation:

* Don (honorific), a form of address in Spain, Portugal, Italy, and their former overseas empires, usually given to nobles or other individuals of high social rank.

* Date of death, as an abbreviati ...

Command paper

A command paper is a document issued by the Government of the United Kingdom, UK Government and presented to Parliament of the United Kingdom, Parliament.

White papers, green papers, treaty, treaties, government responses, draft bills, reports fr ...

s, 1914: Vol. XVIII p. 513

*''Minutes of Evidence and Appendices''

d. 7272 D. or d. may refer to, usually as an abbreviation:

* Don (honorific), a form of address in Spain, Portugal, Italy, and their former overseas empires, usually given to nobles or other individuals of high social rank.

* Date of death, as an abbreviati ...

Command papers, 1914: Vol. XVIII p. 533

External links

The Irish Story archive on the Lockout

Retrieved 2013-07-09 * * *

Church opposition to sending children to England * * * {{Authority control History of Ireland (1801–1923) 1913 labor disputes and strikes 1914 labor disputes and strikes History of County Dublin Labour disputes in Ireland Labour disputes in the United Kingdom 1913 in Ireland 1914 in Ireland