Dragon Mascots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A dragon is a reptilian

The word ''dragon'' entered the

The word ''dragon'' entered the

, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', at Perseus project The Greek and Latin term referred to any great serpent, not necessarily mythological. The Greek word is most likely derived from the Greek verb () meaning "I see", the

Draconic creatures appear in virtually all cultures around the globe and the earliest attested reports of draconic creatures resemble giant snakes. Draconic creatures are first described in the mythologies of the

Draconic creatures appear in virtually all cultures around the globe and the earliest attested reports of draconic creatures resemble giant snakes. Draconic creatures are first described in the mythologies of the

legendary creature

A legendary creature (also mythical or mythological creature) is a type of fictional entity, typically a hybrid, that has not been proven and that is described in folklore (including myths and legends), but may be featured in historical accoun ...

that appears in the folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, rangin ...

of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

have often been depicted as winged, horned, and capable of breathing fire. Dragons in eastern cultures are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, serpentine creatures with above-average intelligence. Commonalities between dragons' traits are often a hybridization of feline, reptilian and avian

Avian may refer to:

* Birds or Aves, winged animals

*Avian (given name) (russian: Авиа́н, link=no), a male forename

Aviation

*Avro Avian, a series of light aircraft made by Avro in the 1920s and 1930s

*Avian Limited, a hang glider manufactur ...

features. Scholars believe huge extinct or migrating crocodiles

Crocodiles (family Crocodylidae) or true crocodiles are large semiaquatic reptiles that live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas and Australia. The term crocodile is sometimes used even more loosely to include all extant memb ...

bear the closest resemblance, especially when encountered in forested or swampy areas, and are most likely the template of modern Oriental dragon imagery.

Etymology

The word ''dragon'' entered the

The word ''dragon'' entered the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the ...

in the early 13th century from Old French

Old French (, , ; Modern French: ) was the language spoken in most of the northern half of France from approximately the 8th to the 14th centuries. Rather than a unified language, Old French was a linkage of Romance dialects, mutually intel ...

''dragon'', which in turn comes from la, draconem (nominative ) meaning "huge serpent, dragon", from Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

, (genitive , ) "serpent, giant seafish".Δράκων, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', at Perseus project The Greek and Latin term referred to any great serpent, not necessarily mythological. The Greek word is most likely derived from the Greek verb () meaning "I see", the

aorist

Aorist (; abbreviated ) verb forms usually express perfective aspect and refer to past events, similar to a preterite. Ancient Greek grammar had the aorist form, and the grammars of other Indo-European languages and languages influenced by th ...

form of which is (). This is thought to have referred to something with a "deadly glance," or unusually bright or "sharp" eyes, or because a snake's eyes appear to be always open; each eye actually sees through a big transparent scale in its eyelids, which are permanently shut. The Greek word probably derives from an Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

base meaning "to see"; the Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cultural diffusion ...

root () also means "to see".

Myth origins

ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

and appear in ancient Mesopotamian art and literature. Stories about storm-gods slaying giant serpents occur throughout nearly all Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

and Near Eastern mythologies. Famous prototypical draconic creatures include the '' mušḫuššu'' of ancient Mesopotamia

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing i ...

; Apep

Apep, also spelled Apepi or Aapep, ( Ancient Egyptian: ; Coptic: Erman, Adolf, and Hermann Grapow, eds. 1926–1953. ''Wörterbuch der aegyptischen Sprache im Auftrage der deutschen Akademien''. 6 vols. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'schen Buc ...

in Egyptian mythology

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyp ...

; Vṛtra in the ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only on ...

''; the Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to some ...

in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

'' Grand'Goule in the

In

In

The word "dragon" has come to be applied to the

The word "dragon" has come to be applied to the

探究中华龙纹设计的历史流变(Exploring the historical evolution of Chinese dragon design)

J].今古文创,2021(46):92-93. However, since the Tang and Song dynasties (618-1279 A.D.), the image of the real dragon symbolizing China's imperial power was no longer the Yinglong with wings, but the common wingless Yellow Dragon in modern times. For the evolution of Yinglong and Huanglong (Yellow Dragon, Scholar Chen Zheng proposed in "Yinglong - the origin of the image of the real dragon" that from the middle of the Zhou Dynasty, Yinglong's wings gradually became the form of flame pattern and cloud pattern at the dragon's shoulder in artistic creation, which derived the wingless long snake shape. The image of Huanglong was used together with the winged Yinglong. Since then, with a series of wars, Chinese civilization suffered heavy losses, resulting in the forgetting of the image of winged Yinglong, and the image of wingless Yellow Dragon replaced the original Yinglong and became the real dragon symbolizing China's imperial power. On this basis, scholars Xiao Congrong(肖聪榕)put forward that the simplified artistic creation of Ying Long's wings by Chinese ancestors is a continuous process, that is, the simplification of dragon's wings is an irreversible trend. Xiao Congrong believes that the phenomenon of "Yellow Dragon" Replacing "Ying Long" can not be avoided regardless of whether Chinese civilization has suffered disaster or not. One of the most famous dragon stories is about the Lord Ye Gao, who loved dragons obsessively, even though he had never seen one. He decorated his whole house with dragon motifs and, seeing this display of admiration, a real dragon came and visited Ye Gao, but the lord was so terrified at the sight of the creature that he ran away. In Chinese legend, the culture hero A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China. The ''

A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China. The '' In China, dragon is thought to have power over rain. Dragons and their associations with rain are the source of the Chinese customs of dragon dancing and dragon boat racing.Dragons are closely associated with rain and

In China, dragon is thought to have power over rain. Dragons and their associations with rain are the source of the Chinese customs of dragon dancing and dragon boat racing.Dragons are closely associated with rain and  Many traditional Chinese customs revolve around dragons. During various holidays, including the Spring Festival and

Many traditional Chinese customs revolve around dragons. During various holidays, including the Spring Festival and

File:Changshadragon.jpg,

Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China. Like some other dragons, most Japanese dragons are water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. Gould writes (1896:248), the Japanese dragon is "invariably figured as possessing three claws". A story about the ''

Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China. Like some other dragons, most Japanese dragons are water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. Gould writes (1896:248), the Japanese dragon is "invariably figured as possessing three claws". A story about the ''

In the ''

In the ''

Ancient people across the

Ancient people across the

In the

In the

describing a shepherd having a fight with a big constriction, constricting snake, calls it " Hesiod also mentions that the hero

Hesiod also mentions that the hero  In the

In the  In the

In the

In the

In the

The modern, western image of a dragon developed in

The modern, western image of a dragon developed in  The oldest recognizable image of a fully modern, western dragon appears in a hand-painted illustration from the medieval manuscript ''MS Harley 3244'', which was produced in around 1260 AD. The dragon in the illustration has two sets of wings and its tail is longer than most modern depictions of dragons, but it clearly displays many of the same distinctive features. Dragons are generally depicted as living in rivers or having an underground lair or cave. They are envisioned as greedy and gluttonous, with voracious appetites. They are often identified with Satan, due to the references to Satan as a "dragon" in the Book of Revelation. The thirteenth-century ''

The oldest recognizable image of a fully modern, western dragon appears in a hand-painted illustration from the medieval manuscript ''MS Harley 3244'', which was produced in around 1260 AD. The dragon in the illustration has two sets of wings and its tail is longer than most modern depictions of dragons, but it clearly displays many of the same distinctive features. Dragons are generally depicted as living in rivers or having an underground lair or cave. They are envisioned as greedy and gluttonous, with voracious appetites. They are often identified with Satan, due to the references to Satan as a "dragon" in the Book of Revelation. The thirteenth-century '' The legend of

The legend of

In Albanian mythology and folklore, ''

In Albanian mythology and folklore, ''

Dragons and dragon motifs are featured in many works of modern literature, particularly within the

Dragons and dragon motifs are featured in many works of modern literature, particularly within the

(in Game of Thrones)

an

(Smaug, as in the movie)

File:Jabberwocky.jpg,

''The Dragon in China and Japan''

, Amsterdam, J. Müller 1913. * * * * *

'' Grand'Goule in the

Poitou

Poitou (, , ; ; Poitevin: ''Poetou'') was a province of west-central France whose capital city was Poitiers. Both Poitou and Poitiers are named after the Pictones Gallic tribe.

Geography

The main historical cities are Poitiers (historical c ...

region in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

; Python, Ladon, Wyvern

A wyvern ( , sometimes spelled wivern) is a legendary winged dragon that has two legs.

The wyvern in its various forms is important in heraldry, frequently appearing as a mascot of schools and athletic teams (chiefly in the United States, U ...

, Kulshedra

The kulshedra or kuçedra is a water, storm, fire and chthonic demon in Albanian mythology and folklore, usually described as a huge multi-headed female serpentine dragon. The kulshedra is believed to spit fire, cause drought, storms, floodi ...

in Albanian Mythology

Albanian folk beliefs ( sq, Besimet folklorike shqiptare) comprise the beliefs expressed in the customs, rituals, myths, legends and tales of the Albanian people. The elements of Albanian mythology are of Paleo-Balkanic origin and almost all ...

and the Lernaean Hydra

The Lernaean Hydra or Hydra of Lerna ( grc-gre, Λερναῖα Ὕδρα, ''Lernaîa Hýdra''), more often known simply as the Hydra, is a snake, serpentine water monster in Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Its lair was the lake of Le ...

in Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities o ...

; Jörmungandr

In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr ( non, Jǫrmungandr, lit=the Vast gand, see Etymology), also known as the Midgard Serpent or World Serpent ( non, Miðgarðsormr), is an unfathomably large sea serpent or worm who dwells in the world sea, encir ...

, Níðhöggr

In Norse mythology, Níðhöggr (''Malice Striker'', in Old Norse traditionally also spelled Níðhǫggr , often anglicized NidhoggWhile the suffix of the name, ''-höggr'', clearly means "striker" the prefix is not as clear. In particular, the ...

, and Fafnir in Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern per ...

; and the dragon from ''Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. ...

''.

Nonetheless, scholars dispute where the idea of a dragon originates from and a wide variety of hypotheses have been proposed.

In his book ''An Instinct for Dragons

''An Instinct for Dragons'' is a book by University of Central Florida anthropologist, David E. Jones, in which he seeks to explain the universality of dragon images in the folklore of human societies. In the introduction, Jones conducts a survey ...

'' (2000), David E. Jones (anthropologist) suggests a hypothesis that humans, like monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomple ...

s, have inherited instinctive reactions to snakes, large cats, and birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predat ...

. He cites a study which found that approximately 39 people in a hundred are afraid of snakes and notes that fear of snakes is especially prominent in children, even in areas where snakes are rare. The earliest attested dragons all resemble snakes or have snakelike attributes. Jones therefore concludes that dragons appear in nearly all cultures because humans have an innate fear of snakes and other animals that were major predators of humans' primate ancestors. Dragons are usually said to reside in "dank caves, deep pools, wild mountain reaches, sea bottoms, haunted forests", all places which would have been fraught with danger for early human ancestors.

In her book ''The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times'' (2000), Adrienne Mayor

Adrienne Mayor (born 1946) is a historian of ancient science and a classical folklorist.

Mayor specializes in ancient history and the study of "folk science", or how pre-scientific cultures interpreted data about the natural world, and how these ...

argues that some stories of dragons may have been inspired by ancient discoveries of fossils belonging to dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s and other prehistoric animals. She argues that the dragon lore of northern India may have been inspired by "observations of oversized, extraordinary bones in the fossilbeds of the Siwalik Hills

The Sivalik Hills, also known as the Shivalik Hills and Churia Hills, are a mountain range of the outer Himalayas that stretches over about from the Indus River eastwards close to the Brahmaputra River, spanning the northern parts of the Indian ...

below the Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

" and that ancient Greek artistic depictions of the Monster of Troy may have been influenced by fossils of ''Samotherium

''Samotherium'' ("beast of Samos") is an extinct genus of Giraffidae from the Miocene and Pliocene of Eurasia and Africa. ''Samotherium'' had two ossicones on its head, and long legs. The ossicones usually pointed upward, and were curved ba ...

'', an extinct species of giraffe whose fossils are common in the Mediterranean region. In China, a region where fossils of large prehistoric animals are common, these remains are frequently identified as "dragon bones" and are commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. It has been described as "fraught with pseudoscience", with the majority of its treatments having no logical mechanism of acti ...

. Mayor, however, is careful to point out that not all stories of dragons and giants are inspired by fossils and notes that Scandinavia has many stories of dragons and sea monsters, but has long "been considered barren of large fossils." In one of her later books, she states that "Many dragon images around the world were based on folk knowledge or exaggerations of living reptiles, such as Komodo dragon

The Komodo dragon (''Varanus komodoensis''), also known as the Komodo monitor, is a member of the monitor lizard family Varanidae that is endemic to the Indonesian islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang. It is the largest extant ...

s, Gila monster

The Gila monster (''Heloderma suspectum'', ) is a species of venomous lizard native to the Southwestern United States and the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora. It is a heavy, typically slow-moving reptile, up to long, and it is the only ve ...

s, iguanas, alligator

An alligator is a large reptile in the Crocodilia order in the genus ''Alligator'' of the family Alligatoridae. The two extant species are the American alligator (''A. mississippiensis'') and the Chinese alligator (''A. sinensis''). Additional ...

s, or, in California, alligator lizards

An alligator lizard is any one of various species of lizards in the family Anguidae that have some shared characteristics.

The term may specifically refer to:

Species of the genus ''Elgaria'':

* Northern alligator lizard (''Elgaria coerulea'')

...

, though this still fails to account for the Scandinavian legends, as no such animals (historical or otherwise) have ever been found in this region."

Robert Blust in ''The Origin Of Dragons'' (2000) argues that, like many other creations of traditional cultures, dragons are largely explicable as products of a convergence of rational pre-scientific speculation about the world of real events. In this case, the event is the natural mechanism governing rainfall and drought, with particular attention paid to the phenomenon of the rainbow.

Egyptian folklore

Egypt

In

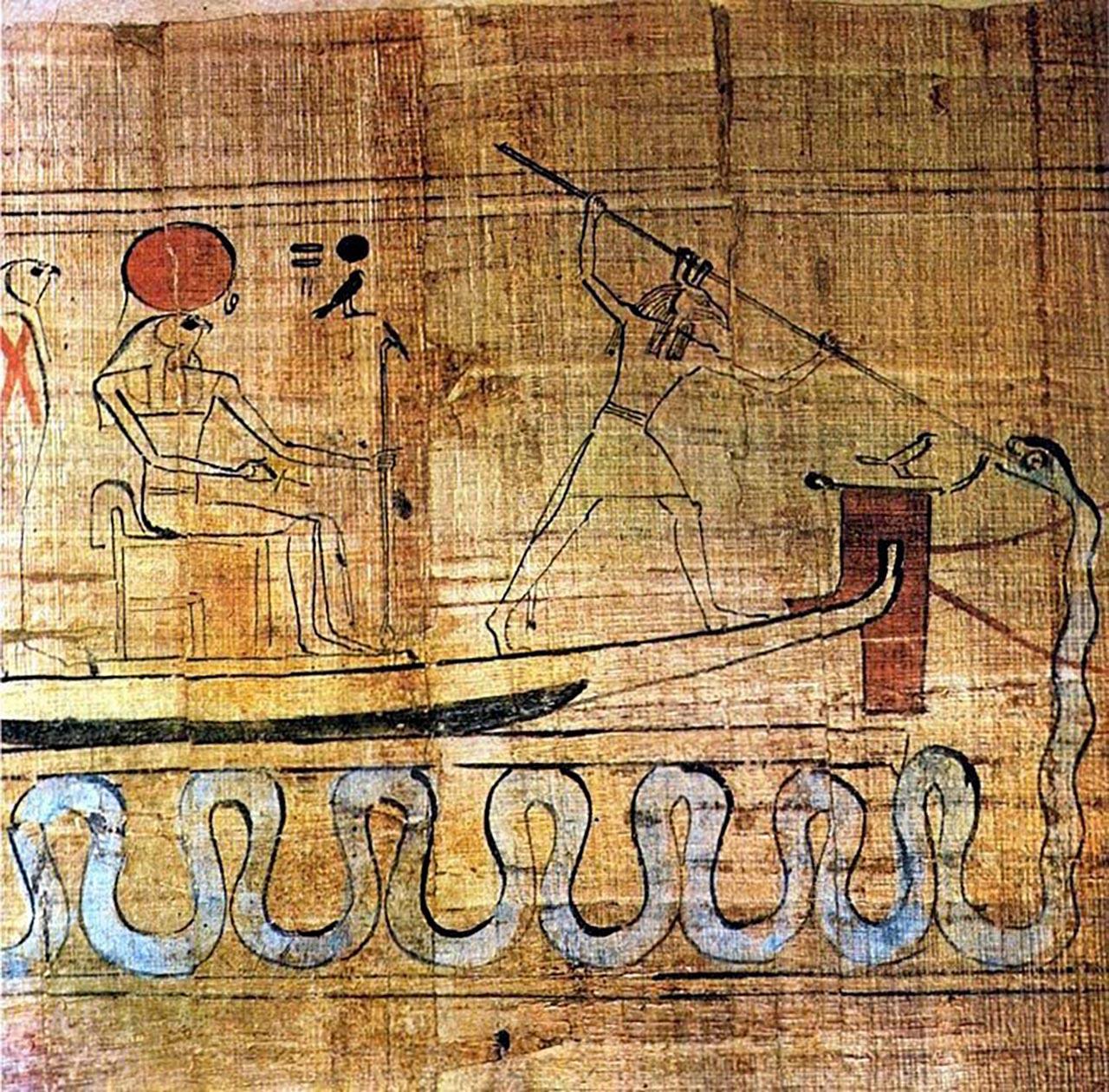

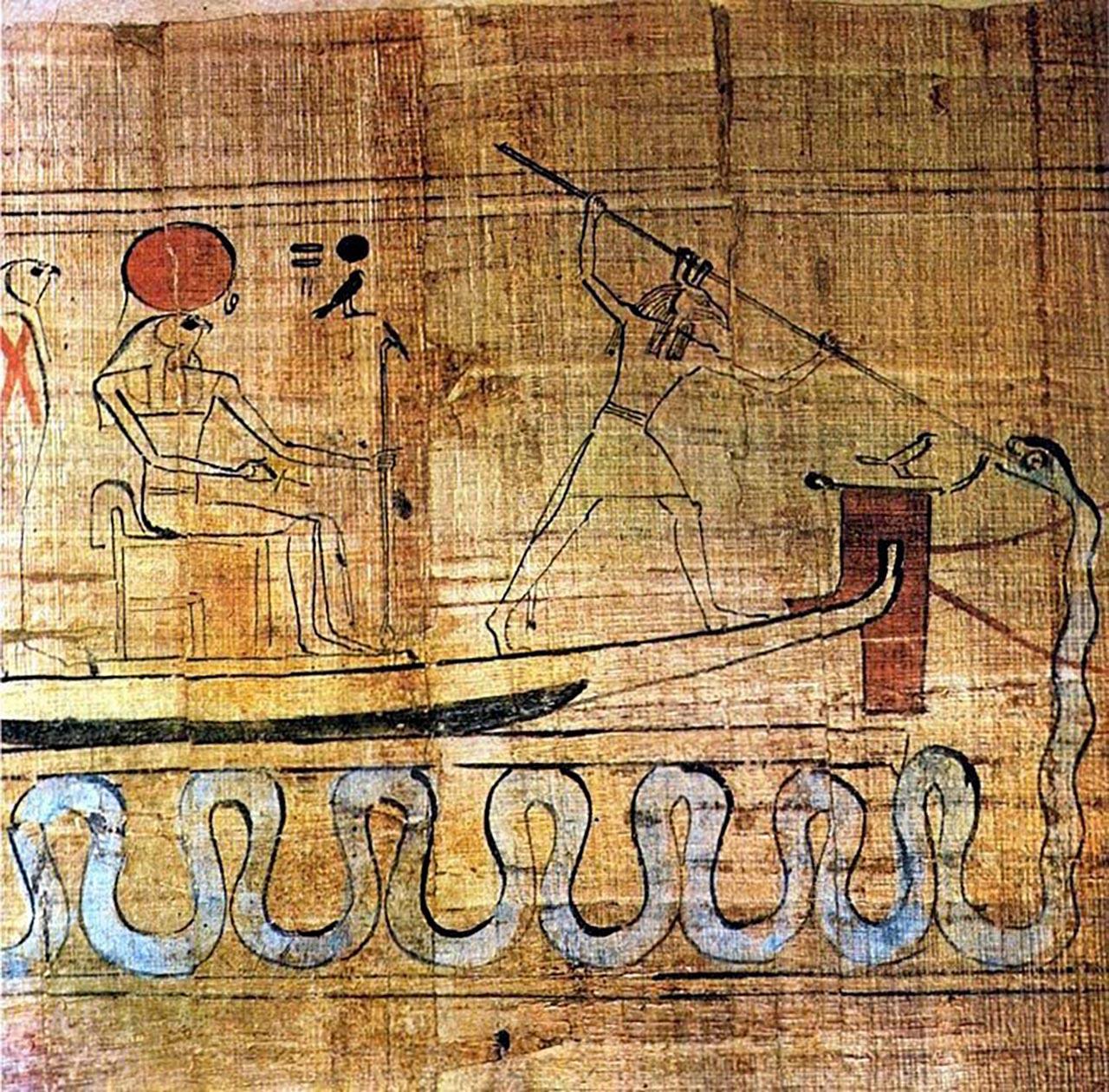

In Egyptian mythology

Egyptian mythology is the collection of myths from ancient Egypt, which describe the actions of the Egyptian gods as a means of understanding the world around them. The beliefs that these myths express are an important part of ancient Egyp ...

, Apep

Apep, also spelled Apepi or Aapep, ( Ancient Egyptian: ; Coptic: Erman, Adolf, and Hermann Grapow, eds. 1926–1953. ''Wörterbuch der aegyptischen Sprache im Auftrage der deutschen Akademien''. 6 vols. Leipzig: J. C. Hinrichs'schen Buc ...

or Apophis is a giant serpentine creature who resides in the Duat

The Duat ( egy, dwꜣt, Egyptological pronunciation "do-aht", cop, ⲧⲏ, also appearing as ''Tuat'', ''Tuaut'' or ''Akert'', ''Amenthes'', ''Amenti'', or ''Neter-khertet'') is the realm of the dead in ancient Egyptian mythology. It has been ...

, the Egyptian Underworld. The Bremner-Rhind papyrus, written in around 310 BC, preserves an account of a much older Egyptian tradition that the setting of the sun is caused by Ra descending to the Duat to battle Apep. In some accounts, Apep is as long as the height of eight men with a head made of flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start ...

. Thunderstorms and earthquakes were thought to be caused by Apep's roar and solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six mon ...

s were thought to be the result of Apep attacking Ra during the daytime. In some myths, Apep is slain by the god Set

Set, The Set, SET or SETS may refer to:

Science, technology, and mathematics Mathematics

*Set (mathematics), a collection of elements

*Category of sets, the category whose objects and morphisms are sets and total functions, respectively

Electro ...

. Nehebkau is another giant serpent who guards the Duat and aided Ra in his battle against Apep. Nehebkau was so massive in some stories that the entire earth was believed to rest atop his coils. Denwen is a giant serpent mentioned in the Pyramid Texts

The Pyramid Texts are the oldest ancient Egyptian funerary texts, dating to the late Old Kingdom. They are the earliest known corpus of ancient Egyptian religious texts. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved onto the subterran ...

whose body was made of fire and who ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed all the gods of the Egyptian pantheon. He was ultimately defeated by the Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

, a victory which affirmed the Pharaoh's divine right to rule.

The ouroboros

The ouroboros or uroboros () is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon eating its own tail. The ouroboros entered Western tradition via ancient Egyptian iconography and the Greek magical tradition. It was adopted as a symbol in Gnost ...

was a well-known Egyptian symbol of a serpent swallowing its own tail. The precursor to the ouroboros was the "Many-Faced", a serpent with five heads, who, according to the Amduat

The Amduat ( egy, jmj dwꜣt, literally "That Which Is In the Afterworld", also translated as "Text of the Hidden Chamber Which is in the Underworld" and "Book of What is in the Underworld"; ar, كتاب الآخرة, Kitab al-Akhira) is an imp ...

, the oldest surviving Book of the Afterlife, was said to coil around the corpse of the sun god Ra protectively. The earliest surviving depiction of a "true" ouroboros comes from the gilded shrines in the tomb of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun (, egy, twt-ꜥnḫ-jmn), Egyptological pronunciation Tutankhamen () (), sometimes referred to as King Tut, was an Egyptian pharaoh who was the last of his royal family to rule during the end of the Eighteenth Dynasty (ruled ...

. In the early centuries AD, the ouroboros was adopted as a symbol by Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized p ...

Christians and chapter 136 of the ''Pistis Sophia

''Pistis Sophia'' ( grc-koi, Πίστις Σοφία) is a Gnostic text discovered in 1773, possibly written between the 3rd and 4th centuries AD. The existing manuscript, which some scholars place in the late 4th century, relates one Gnostic g ...

'', an early Gnostic text, describes "a great dragon whose tail is in its mouth". In medieval alchemy, the ouroboros became a typical western dragon with wings, legs, and a tail. A famous image of the dragon gnawing on its tail from the eleventh-century Codex Marcianus was copied in numerous works on alchemy.

Asian folklore

East Asia

China

The word "dragon" has come to be applied to the

The word "dragon" has come to be applied to the legendary creature

A legendary creature (also mythical or mythological creature) is a type of fictional entity, typically a hybrid, that has not been proven and that is described in folklore (including myths and legends), but may be featured in historical accoun ...

in Chinese mythology

Chinese mythology () is mythology that has been passed down in oral form or recorded in literature in the geographic area now known as Greater China. Chinese mythology includes many varied myths from regional and cultural traditions.

Much of ...

, ''loong'' (traditional 龍, simplified 龙, Japanese simplified 竜, Pinyin

Hanyu Pinyin (), often shortened to just pinyin, is the official romanization system for Standard Mandarin Chinese in China, and to some extent, in Singapore and Malaysia. It is often used to teach Mandarin, normally written in Chinese fo ...

''lóng''), which is associated with good fortune, and many East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

n deities and demigods have dragons as their personal mounts or companions. Dragons were also identified with the Emperor of China

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heav ...

, who, during later Chinese imperial history, was the only one permitted to have dragons on his house, clothing, or personal articles.

Archaeologist Zhōu Chong-Fa believes that the Chinese word for dragon is an onomatopoeia

Onomatopoeia is the process of creating a word that phonetically imitates, resembles, or suggests the sound that it describes. Such a word itself is also called an onomatopoeia. Common onomatopoeias include animal noises such as ''oink'', ''m ...

of the sound of thunder or ''lùhng'' in Cantonese

Cantonese ( zh, t=廣東話, s=广东话, first=t, cy=Gwóngdūng wá) is a language within the Chinese (Sinitic) branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages originating from the city of Guangzhou (historically known as Canton) and its surrounding a ...

.

The Chinese dragon () is the highest-ranking creature in the Chinese animal hierarchy. Its origins are vague, but its "ancestors can be found on Neolithic pottery as well as Bronze Age ritual vessels." A number of popular stories deal with the rearing of dragons. The '' Zuo zhuan'', which was probably written during the Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in History of China#Ancient China, ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded ...

, describes a man named Dongfu, a descendant of Yangshu'an, who loved dragons and, because he could understand a dragon's will, he was able to tame them and raise them well. He served Emperor Shun, who gave him the family name Huanlong, meaning "dragon-raiser". In another story, Kong Jia

Kǒng Jiǎ (孔甲) was a king of ancient China, family name Sì (姒), the 14th ruler of the semi-legendary Xia dynasty. He possibly ruled for 31 years.

Family

Kong Jia was a son of King Bù Jiàng and an unknown woman and grandson of King ...

, the fourteenth emperor of the Xia dynasty

The Xia dynasty () is the first dynasty in traditional Chinese historiography. According to tradition, the Xia dynasty was established by the legendary Yu the Great, after Shun, the last of the Five Emperors, gave the throne to him. In tradit ...

, was given a male and a female dragon as a reward for his obedience to the god of heaven, but could not train them, so he hired a dragon-trainer named Liulei, who had learned how to train dragons from Huanlong. One day, the female dragon died unexpectedly, so Liulei secretly chopped her up, cooked her meat, and served it to the king, who loved it so much that he demanded Liulei to serve him the same meal again. Since Liulei had no means of procuring more dragon meat, he fled the palace.

The image of the Chinese dragon was roughly established in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, but there was no great change for a long time. In the Han dynasty(202 B.C.-220 A.D.), Yinglong, as a symbol of feudal imperial power, frequently appeared in Royal Dragon vessels, which means that most of the dragon image designs used by the royal family in the Han Dynasty are Yinglong patterns. Yinglong is a winged dragon in ancient Chinese legend. At present, the literature records of Yinglong's winged image can be tested from "Guangya"(广雅), "wide elegant" during the Three Kingdoms period, but Yinglong's winged design has been found in bronze ware from the Shang and Zhou Dynasties to stone carvings, silk paintings and lacquerware of the Han Dynasty. The literature records of Yinglong can be traced back to the documents of the pre-Qin period, such as "Classic of Mountains and Seas", "Chuci" and so on. According to the records in "Classic of Mountains and Seas", the Chinese mythology in 2200 years ago, Ying long had the main characteristics of later Chinese dragons - the power to control the sky and the noble mythical status.XiaoCongRon探究中华龙纹设计的历史流变(Exploring the historical evolution of Chinese dragon design)

J].今古文创,2021(46):92-93. However, since the Tang and Song dynasties (618-1279 A.D.), the image of the real dragon symbolizing China's imperial power was no longer the Yinglong with wings, but the common wingless Yellow Dragon in modern times. For the evolution of Yinglong and Huanglong (Yellow Dragon, Scholar Chen Zheng proposed in "Yinglong - the origin of the image of the real dragon" that from the middle of the Zhou Dynasty, Yinglong's wings gradually became the form of flame pattern and cloud pattern at the dragon's shoulder in artistic creation, which derived the wingless long snake shape. The image of Huanglong was used together with the winged Yinglong. Since then, with a series of wars, Chinese civilization suffered heavy losses, resulting in the forgetting of the image of winged Yinglong, and the image of wingless Yellow Dragon replaced the original Yinglong and became the real dragon symbolizing China's imperial power. On this basis, scholars Xiao Congrong(肖聪榕)put forward that the simplified artistic creation of Ying Long's wings by Chinese ancestors is a continuous process, that is, the simplification of dragon's wings is an irreversible trend. Xiao Congrong believes that the phenomenon of "Yellow Dragon" Replacing "Ying Long" can not be avoided regardless of whether Chinese civilization has suffered disaster or not. One of the most famous dragon stories is about the Lord Ye Gao, who loved dragons obsessively, even though he had never seen one. He decorated his whole house with dragon motifs and, seeing this display of admiration, a real dragon came and visited Ye Gao, but the lord was so terrified at the sight of the creature that he ran away. In Chinese legend, the culture hero

Fu Hsi

Fuxi or Fu Hsi (伏羲 ~ 伏犧 ~ 伏戲) is a culture hero in Chinese legend and mythology, credited along with his sister and wife Nüwa with creating humanity and the invention of music, hunting, fishing, domestication, and cooking as well a ...

is said to have been crossing the Lo River, when he saw the '' lung ma'', a Chinese horse-dragon with seven dots on its face, six on its back, eight on its left flank, and nine on its right flank. He was so moved by this apparition that, when he arrived home, he drew a picture of it, including the dots. He later used these dots as letters and invented Chinese writing

Written Chinese () comprises Chinese characters used to represent the Chinese language. Chinese characters do not constitute an alphabet or a compact syllabary. Rather, the writing system is roughly Logogram, logosyllabic; that is, a character gen ...

, which he used to write his book ''I Ching

The ''I Ching'' or ''Yi Jing'' (, ), usually translated ''Book of Changes'' or ''Classic of Changes'', is an ancient Chinese divination text that is among the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zh ...

''. In another Chinese legend, the physician Ma Shih Huang is said to have healed a sick dragon. Another legend reports that a man once came to the healer Lo Chên-jen, telling him that he was a dragon and that he needed to be healed. After Lo Chên-jen healed the man, a dragon appeared to him and carried him to heaven.

In the ''Shanhaijing

The ''Classic of Mountains and Seas'', also known as ''Shan Hai Jing'', formerly romanized as the ''Shan-hai Ching'', is a Chinese classic text and a compilation of mythic geography and beasts. Early versions of the text may have existed sin ...

'', a classic mythography probably compiled mostly during the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

, various deities and demigods are associated with dragons. One of the most famous Chinese dragons is Ying Long ("responding dragon"), who helped the Huangdi, the Yellow Emperor, defeat the tyrant Chiyou

Chiyou (蚩尤, ) is a mythological being that appears in East Asian mythology.

Individual

According to the Song dynasty history book '' Lushi'', Chiyou's surname was Jiang (), and he was a descendant of flame.

According to legend, Chiyou had a ...

. The dragon Zhulong ("torch dragon") is a god "who composed the universe with his body." In the ''Shanhaijing'', many mythic heroes are said to have been conceived after their mothers copulated with divine dragons, including Huangdi, Shennong

Shennong (), variously translated as "Divine Farmer" or "Divine Husbandman", born Jiang Shinian (), was a mythological Chinese ruler known as the first Yan Emperor who has become a deity in Chinese and Vietnamese folk religion. He is vene ...

, Emperor Yao

Emperor Yao (; traditionally c. 2356 – 2255 BCE) was a legendary Chinese ruler, according to various sources, one of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors.

Ancestry and early life

Yao's ancestral name is Yi Qi () or Qi (), clan name i ...

, and Emperor Shun

Emperor Shun () was a legendary leader of ancient China, regarded by some sources as one of the Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors being the last of the Five Emperors. Tradition holds that he lived sometime between 2294 and 2184 BC. Tradition a ...

. The god Zhurong

Zhurong (), also known as Chongli (), is an important personage in Chinese mythology and Chinese folk religion. According to the '' Huainanzi'' and the philosophical texts of Mozi and his followers, Zhurong is a god of fire and of the south.

Th ...

and the emperor Qi are both described as being carried by two dragons, as are Huangdi, Zhuanxu

Zhuanxu (Chinese: trad. , simp. , pinyin ''Zhuānxū''), also known as Gaoyang ( t , s , p ''Gāoyáng''), was a mythological emperor of ancient China.

In the traditional account recorded by Sima Qian, Z ...

, Yuqiang Yuqiang (, alternatively Yujiang 禺疆 or Yujing 禺京), in Chinese mythology is one of the descendants of Huang Di, the "Yellow Emperor". Yuqiang was also the god of the north sea and a wind god. His father was Yuhao, another sea god. Some accou ...

, and Roshou in various other texts. According to the ''Huainanzi

The ''Huainanzi'' is an ancient Chinese text that consists of a collection of essays that resulted from a series of scholarly debates held at the court of Liu An, Prince of Huainan, sometime before 139. The ''Huainanzi'' blends Daoist, Confuci ...

'', an evil black dragon once caused a destructive deluge, which was ended by the mother goddess Nüwa

Nüwa, also read Nügua, is the mother goddess of Chinese mythology. She is credited with creating humanity and repairing the Pillar of Heaven.

As creator of mankind, she molded humans individually by hand with yellow clay.

In the Huaina ...

by slaying the dragon.

A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China. The ''

A large number of ethnic myths about dragons are told throughout China. The ''Houhanshu

The ''Book of the Later Han'', also known as the ''History of the Later Han'' and by its Chinese name ''Hou Hanshu'' (), is one of the Twenty-Four Histories and covers the history of the Han dynasty from 6 to 189 CE, a period known as the Later ...

'', compiled in the fifth century BC by Fan Ye, reports a story belonging to the Ailaoyi people, which holds that a woman named Shayi who lived in the region around Mount Lao

Mount Lao, or Laoshan (), is a mountain located near the East China Sea on the southeastern coastline of the Shandong Peninsula in China. The mountain is culturally significant due to its long affiliation with Taoism and is often regarded as on ...

became pregnant with ten sons after being touched by a tree trunk floating in the water while fishing. She gave birth to the sons and the tree trunk turned into a dragon, who asked to see his sons. The woman showed them to him, but all of them ran away except for the youngest, who the dragon licked on the back and named Jiu Long, meaning "sitting back". The sons later elected him king and the descendants of the ten sons became the Ailaoyi people, who tattoo

A tattoo is a form of body modification made by inserting tattoo ink, dyes, and/or pigments, either indelible or temporary, into the dermis layer of the skin to form a design. Tattoo artists create these designs using several tattooing ...

ed dragons on their backs in honor of their ancestor. The Miao people

The Miao are a group of linguistically-related peoples living in Southern China and Southeast Asia, who are recognized by the government of China as one of the 56 official ethnic groups. The Miao live primarily in southern China's mountains, in ...

of southwest China have a story that a divine dragon created the first humans by breathing on monkeys that came to play in his cave. The Han people

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive var ...

have many stories about Short-Tailed Old Li, a black dragon who was born to a poor family in Shandong

Shandong ( , ; ; Chinese postal romanization, alternately romanized as Shantung) is a coastal Provinces of China, province of the China, People's Republic of China and is part of the East China region.

Shandong has played a major role in His ...

. When his mother saw him for the first time, she fainted and, when his father came home from the field and saw him, he hit him with a spade and cut off part of his tail. Li burst through the ceiling and flew away to the Black Dragon River in northeast China, where he became the god of that river. On the anniversary of his mother's death on the Chinese lunar calendar, Old Li returns home, causing it to rain. He is still worshipped as a rain god.

drought

A drought is defined as drier than normal conditions.Douville, H., K. Raghavan, J. Renwick, R.P. Allan, P.A. Arias, M. Barlow, R. Cerezo-Mota, A. Cherchi, T.Y. Gan, J. Gergis, D. Jiang, A. Khan, W. Pokam Mba, D. Rosenfeld, J. Tierney, an ...

is thought to be caused by a dragon's laziness. Prayers invoking dragons to bring rain are common in Chinese texts. The ''Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals

The ''Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals'' () is one of the works attributed to Dong Zhongshu that has survived to the present, though its compilation might have continued past his lifetime into the 4th century. It is 82 chapters long ...

'', attributed to the Han dynasty scholar Dong Zhongshu

Dong Zhongshu (; 179–104 BC) was a Chinese philosopher, politician, and writer of the Han Dynasty. He is traditionally associated with the promotion of Confucianism as the official ideology of the Chinese imperial state. He apparently favored ...

, prescribes making clay figurines of dragons during a time of drought and having young men and boys pace and dance among the figurines in order to encourage the dragons to bring rain. Texts from the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

advise hurling the bone of a tiger or dirty objects into the pool where the dragon lives; since dragons cannot stand tigers or dirt, the dragon of the pool will cause heavy rain to drive the object out. Rainmaking rituals invoking dragons are still very common in many Chinese villages, where each village has its own god said to bring rain and many of these gods are dragons. The Chinese dragon kings are thought of as the inspiration for the Hindu myth of the naga. According to these stories, every body of water is ruled by a dragon king, each with a different power, rank, and ability, so people began establishing temples across the countryside dedicated to these figures.

Many traditional Chinese customs revolve around dragons. During various holidays, including the Spring Festival and

Many traditional Chinese customs revolve around dragons. During various holidays, including the Spring Festival and Lantern Festival

The Lantern Festival ( zh, t=元宵節, s=元宵节, first=t, hp=Yuánxiāo jié), also called Shangyuan Festival ( zh, t=上元節, s=上元节, first=t, hp=Shàngyuán jié), is a Chinese traditional festival celebrated on the fifteenth d ...

, villagers will construct an approximately sixteen-foot-long dragon from grass, cloth, bamboo strips, and paper, which they will parade through the city as part of a dragon dance

Dragon dance () is a form of traditional dance and performance in Chinese culture. Like the lion dance, it is most often seen during festive celebrations. The dance is performed by a team of experienced dancers who manipulate a long flexible ...

. The original purpose of this ritual was to bring good weather and a strong harvest, but now it is done mostly only for entertainment. During the Duanwu

The Dragon Boat Festival ( zh, s=端午节, t=端午節) is a traditional Chinese holiday which occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar, which corresponds to late May or June in the Gregorian calendar.

Names

The Engl ...

festival, several villages, or even a whole province, will hold a dragon boat race

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

, in which people race across a body of water in boats carved to look like dragons, while a large audience watches on the banks. The custom is traditionally said to have originated after the poet Qu Yuan

Qu Yuan ( – 278 BCE) was a Chinese poet and politician in the State of Chu during the Warring States period. He is known for his patriotism and contributions to classical poetry and verses, especially through the poems of the '' ...

committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River

The Miluo River (, and with modified Wade–Giles using the form Mi-lo) is located on the eastern bank of Dongting Lake, the largest tributary of the Xiang River in the northern Hunan Province. It is an important river in the Dongting Lake watershe ...

and people raced out in boats hoping to save him, but most historians agree that the custom actually originated much earlier as a ritual to avert ill fortune. Starting during the Han dynasty and continuing until the Qing dynasty, the Chinese emperor

''Huangdi'' (), translated into English as Emperor, was the superlative title held by monarchs of China who ruled various imperial regimes in Chinese history. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was considered the Son of Heave ...

gradually became closely identified with dragons, and emperors themselves claimed to be the incarnations of a divine dragon. Eventually, dragons were only allowed to appear on clothing, houses, and articles of everyday use belonging to the emperor and any commoner who possessed everyday items bearing the image of the dragon were ordered to be executed. After the last Chinese emperor was overthrown in 1911, this situation changed and now many ordinary Chinese people identify themselves as descendants of dragons.

The impression of dragons in a large number of Asian countries has been influenced by Chinese culture, such as Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and so on. Chinese tradition has always used the dragon totem as the national emblem, and the "Yellow Dragon flag" of the Qing dynasty has influenced the impression that China is a dragon in many European countries.

Silk painting depicting a man riding a dragon

''Silk painting depicting a man riding a dragon'' (人物御龍帛畫) is a Chinese painting on silk from the Warring States period (475-221 BC). It was discovered in the Zidanku Tomb no. 1 in Changsha, Hunan Province in 1973. Now in the Huna ...

, dated to 5th–3rd centuries BC

File:Attributed to Li Zhaodao Dragon-boat Race. Palace Museum, Beijing.jpg, Tang dynasty painting of a dragon boat race

A dragon is a reptilian legendary creature that appears in the folklore of many cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as ...

attributed to Li Zhaodao

File:Flag of China (1889–1912).svg, Flag of the Qing dynasty

The flag of the Qing dynasty was an emblem adopted in the late 19th century featuring the Azure Dragon on a plain yellow field with the red flaming pearl in the upper left corner. It became the first national flag of China and is usually refe ...

from 1889 to 1912, showing a Chinese dragon

File:Dragon on Longshan Temple.JPG, Dragon sculpture on top of Lungshan Temple, Taipei, Taiwan

File:Dança do dragão.jpg, Members of the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/ Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a metro ...

performing for Chinese New Year, at Crown Casino

Crown Melbourne (also referred to as Crown Casino and Entertainment Complex) is a casino and resort located on the south bank of the Yarra River, in Melbourne, Australia. Crown Casino is a unit of Crown Limited, and the first casino of th ...

, demonstrate a basic "corkscrew" routine

Korea

The Korean dragon is in many ways similar in appearance to other East Asian dragons such as the Chinese andJapanese dragon

Japanese dragons (, ''Nihon no ryū'') are diverse legendary creatures in Japanese mythology and folklore. Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China, Korea and the Indian subcontinent. The ...

s. It differs from the Chinese dragon in that it developed a longer beard. Very occasionally a dragon may be depicted as carrying an orb known as the Yeouiju (여의주), the Korean name for the mythical Cintamani

Cintāmaṇi ( Sanskrit; Devanagari: चिंतामणि; Chinese: 如意寶珠; Pinyin: ''Rúyì bǎozhū''; Japanese Romaji: ''Nyoihōju; Tamil:சிந்தாமணி''), also spelled as Chintamani (or the ''Chintamani Stone''), i ...

, in its claws or its mouth. It was said that whoever could wield the Yeouiju was blessed with the abilities of omnipotence and creation at will, and that only four-toed dragons (who had thumbs with which to hold the orbs) were both wise and powerful enough to wield these orbs, as opposed to the lesser, three-toed dragons. As with China, the number nine is significant and auspicious in Korea, and dragons were said to have 81 (9×9) scales on their backs, representing yang essence. Dragons in Korean mythology are primarily benevolent beings related to water and agriculture, often considered bringers of rain and clouds. Hence, many Korean dragons are said to have resided in rivers, lakes, oceans, or even deep mountain ponds. And human journeys to undersea realms, and especially the undersea palace of the Dragon King (용왕), are common in Korean folklore.

In Korean myths, some kings who founded kingdoms were described as descendants of dragons because the dragon was a symbol of the monarch. Lady Aryeong

Lady Aryeong (, a.k.a. Al-yeong, Al-yong) was married to Hyeokgeose of Silla who was the founder of Silla. According to ''Samguk Yusa'' (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms), Aryeong was born from the left side of the dragon which appeared near th ...

, who was the first queen of Silla

Silla or Shilla (57 BCE – 935 CE) ( , Old Korean: Syera, Old Japanese: Siraki2) was a Korean kingdom located on the southern and central parts of the Korean Peninsula. Silla, along with Baekje and Goguryeo, formed the Three Kingdoms o ...

is said to have been born from a cockatrice

A cockatrice is a mythical beast, essentially a two-legged dragon, wyvern, or serpent-like creature with a rooster's head. Described by Laurence Breiner as "an ornament in the drama and poetry of the Elizabethans", it was featured prominently i ...

, while the grandmother of Taejo of Goryeo

Taejo of Goryeo (31 January 877 – 4 July 943), also known as Taejo Wang Geon (; ), was the founder of the Goryeo dynasty, which ruled Korea from the 10th to the 14th century. Taejo ruled from 918 to 943, achieving unification of the Later Three ...

, founder of Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificat ...

, was reportedly the daughter of the dragon king of the West Sea. And King Munmu of Silla, who on his deathbed wished to become a dragon of the East Sea in order to protect the kingdom. Dragon patterns were used exclusively by the royal family. The royal robe was also called the dragon robe (용포). In Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and r ...

, the royal insignia, featuring embroidered dragons, were attached to the robe's shoulders, the chest, and back. The King wore five-taloned dragon insignia while the Crown Prince wore four-taloned dragon insignia.

Korean folk mythology states that most dragons were originally Imugis (이무기), or lesser dragons, which were said to resemble gigantic serpents. There are a few different versions of Korean folklore that describe both what imugis are and how they aspire to become full-fledged dragons. Koreans thought that an Imugi could become a true dragon, ''yong'' or ''mireu'', if it caught a Yeouiju which had fallen from heaven. Another explanation states they are hornless creatures resembling dragons who have been cursed and thus were unable to become dragons. By other accounts, an Imugi is a ''proto-dragon'' which must survive one thousand years in order to become a fully fledged dragon. In either case they are said to be large, benevolent, python-like creatures that live in water or caves, and their sighting is associated with good luck.

Japan

Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China. Like some other dragons, most Japanese dragons are water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. Gould writes (1896:248), the Japanese dragon is "invariably figured as possessing three claws". A story about the ''

Japanese dragon myths amalgamate native legends with imported stories about dragons from China. Like some other dragons, most Japanese dragons are water deities associated with rainfall and bodies of water, and are typically depicted as large, wingless, serpentine creatures with clawed feet. Gould writes (1896:248), the Japanese dragon is "invariably figured as possessing three claws". A story about the ''samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They ...

'' Minamoto no Mitsunaka

was a Japanese samurai and court official of the Heian period. He served as ''Chinjufu-shōgun'' and acting governor of Settsu Province''.'' His association with the Fujiwara clan made him one of the wealthiest and most powerful courtiers of his ...

tells that, while he was hunting in his own territory of Settsu, he dreamt under a tree and had a dream in which a beautiful woman appeared to him and begged him to save her land from a giant serpent which was defiling it. Mitsunaka agreed to help and the maiden gave him a magnificent horse. When he woke up, the seahorse was standing before him. He rode it to the Sumiyoshi temple, where he prayed for eight days. Then he confronted the serpent and slew it with an arrow.

It was believed that dragons could be appeased or exorcised with metal. Nitta Yoshisada

was a samurai lord of the Nanboku-chō period Japan. He was the head of the Nitta clan in the early fourteenth century, and supported the Southern Court of Emperor Go-Daigo in the Nanboku-chō period. He famously marched on Kamakura, besieging ...

is said to have hurled a famous sword into the sea at Sagami to appease the dragon-god of the sea and Ki no Tsurayuki

was a Japanese author, poet and court noble of the Heian period. He is best known as the principal compiler of the ''Kokin Wakashū'', also writing its Japanese Preface, and as a possible author of the '' Tosa Diary'', although this was publish ...

threw a metal mirror into the sea at Sumiyoshi for the same purpose. Japanese Buddhism has also adapted dragons by subjecting them to Buddhist law

The dharmachakra ( Sanskrit: धर्मचक्र; Pali: ''dhammacakka'') or wheel of dharma is a widespread symbol used in Indian religions such as Hinduism, Jainism, and especially Buddhism.John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, ''The Circ ...

; the Japanese Buddhist deities Benten

Benzaiten (''shinjitai'': 弁才天 or 弁財天; ''kyūjitai'': 辯才天, 辨才天, or 辨財天, lit. "goddess of eloquence"), also simply known as Benten (''shinjitai'': 弁天; ''kyūjitai'': 辯天 / 辨天), is a Japanese Buddhist g ...

and Kwannon are often shown sitting or standing on the back of a dragon. Several Japanese ''sennin

''Xian'' () refers to a person or similar entity having a long life or being immortal. The concept of ''xian'' has different implications dependent upon the specific context: philosophical, religious, mythological, or other symbolic or cultural ...

'' ("immortals") have taken dragons as their mounts. Bômô is said to have hurled his staff into a puddle of water, causing a dragon to come forth and let him ride it to heaven. The '' rakan'' Handaka is said to have been able to conjure a dragon out of a bowl, which he is often shown playing with on ''kagamibuta''. The ''shachihoko

A – or simply – is a sea monster in Japanese folklore with the head of a tiger and the body of a carp covered entirely in black or grey scales.Joya. ''Japan and Things Japanese.'' Taylor and Francis, 2017;2016;, doi:10.4324/9780203041130. ...

'' is a creature with the head of a dragon, a bushy tail, fishlike scales, and sometimes fire emerging from its armpits. The ''fun'' has the head of a dragon, feathered wings, and the tail and claws of a bird. A white dragon was believed to reside in a pool in Yamashiro Province

was a province of Japan, located in Kinai. It overlaps the southern part of modern Kyoto Prefecture on Honshū. Aliases include , the rare , and . It is classified as an upper province in the '' Engishiki''.

Yamashiro Province included Kyot ...

and, every fifty years, it would turn into a bird called the Ogonchô, which had a call like the "howling of a wild dog". This event was believed to herald terrible famine. In the Japanese village of Okumura, near Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

, during times of drought, the villagers would make a dragon effigy out of straw, magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendr ...

leaves, and bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, ...

and parade it through the village to attract rainfall.

South Asia

India

In the ''

In the ''Rigveda

The ''Rigveda'' or ''Rig Veda'' ( ', from ' "praise" and ' "knowledge") is an ancient Indian collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns (''sūktas''). It is one of the four sacred canonical Hindu texts ('' śruti'') known as the Vedas. Only on ...

'', the oldest of the four Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

, Indra

Indra (; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is the king of the devas (god-like deities) and Svarga (heaven) in Hindu mythology. He is associated with the sky, lightning, weather, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war. volumes/ref> I ...

, the Vedic god of storms, battles Vṛtra, a giant serpent who represents drought. Indra kills Vṛtra using his ''vajra

The Vajra () is a legendary and ritual weapon, symbolising the properties of a diamond (indestructibility) and a thunderbolt (irresistible force).

The vajra is a type of club with a ribbed spherical head. The ribs may meet in a ball-shap ...

'' (thunderbolt) and clears the path for rain, which is described in the form of cattle: "You won the cows, hero, you won the Soma

Soma may refer to:

Businesses and brands

* SOMA (architects), a New York–based firm of architects

* Soma (company), a company that designs eco-friendly water filtration systems

* SOMA Fabrications, a builder of bicycle frames and other bicycle ...

,/You freed the seven streams to flow" (''Rigveda'' 1.32.12). In another Rigvedic legend, the three-headed serpent Viśvarūpa, the son of Tvaṣṭṛ, guards a wealth of cows and horses. Indra delivers Viśvarūpa to a god named Trita Āptya, who fights and kills him and sets his cattle free. Indra cuts off Viśvarūpa's heads and drives the cattle home for Trita. This same story is alluded to in the Younger Avesta, in which the hero Thraētaona, the son of Āthbya, slays the three-headed dragon Aži Dahāka

Zahhāk or Zahāk () ( fa, ضحّاک), also known as Zahhak the Snake Shoulder ( fa, ضحاک ماردوش, Zahhāk-e Mārdoush), is an evil figure in Persian mythology, evident in ancient Persian folklore as Azhi Dahāka ( fa, اژی دهاک) ...

and takes his two beautiful wives as spoils. Thraētaona's name (meaning "third grandson of the waters") indicates that Aži Dahāka, like Vṛtra, was seen as a blocker of waters and cause of drought.

The Druk ( dz, འབྲུག་), also known as 'Thunder Dragon', is one of the National symbols of Bhutan

The national symbols of Bhutan include the national flag, national emblem, national anthem, and the mythical ''druk'' thunder featured in all three. Other distinctive symbols of Bhutan and its dominant Ngalop culture include Dzongkha, the national ...

. In the Dzongkha

Dzongkha (; ) is a Sino-Tibetan language that is the official and national language of Bhutan. It is written using the Tibetan script.

The word means "the language of the fortress", from ' "fortress" and ' "language". , Dzongkha had 171,080 ...

language, Bhutan

Bhutan (; dz, འབྲུག་ཡུལ་, Druk Yul ), officially the Kingdom of Bhutan,), is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is situated in the Eastern Himalayas, between China in the north and India in the south. A mountainou ...

is known as ''Druk Yul'' "Land of Druk", and Bhutanese leaders are called Druk Gyalpo

The Druk Gyalpo (; 'Dragon King') is the head of state of the Kingdom of Bhutan. In the Dzongkha language, Bhutan is known as ''Drukyul'' which translates as "The Land of the Thunder Dragon". Thus, while kings of Bhutan are known as ''Druk ...

, "Thunder Dragon Kings". The druk was adopted as an emblem by the Drukpa Lineage

The Drukpa Kagyu (), or simply Drukpa, sometimes called either Dugpa or " Red Hat sect" in older sources,

, which originated in Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa people, ...

and later spread to Bhutan.

Southeast Asia

Vietnam

The Vietnamese dragon ( vi, rồng 龍) was a mythical creature that was often used as a deity symbol and associated with royalty. Similar to other cultures, dragons in Vietnamese culture represent yang and godly being associated with creation and life.West Asia

Ancient

=Mesopotamia

= Ancient people across the

Ancient people across the Near East

The ''Near East''; he, המזרח הקרוב; arc, ܕܢܚܐ ܩܪܒ; fa, خاور نزدیک, Xāvar-e nazdik; tr, Yakın Doğu is a geographical term which roughly encompasses a transcontinental region in Western Asia, that was once the hist ...

believed in creatures similar to what modern people call "dragons". These ancient people were unaware of the existence of dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

s or similar creatures in the distant past. References to dragons of both benevolent and malevolent characters occur throughout ancient Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n literature. In Sumerian poetry

Sumerian literature constitutes the earliest known corpus of recorded literature, including the religious writings and other traditional stories maintained by the Sumerian civilization and largely preserved by the later Akkadian and Babylonian em ...

, great kings are often compared to the '' ušumgal'', a gigantic, serpentine monster. A draconic creature with the foreparts of a lion and the hind-legs, tail, and wings of a bird appears in Mesopotamian artwork from the Akkadian Period ( 2334 – 2154 BC) until the Neo-Babylonian Period (626 BC–539 BC). The dragon is usually shown with its mouth open. It may have been known as the ''(ūmu) nā’iru'', which means "roaring weather beast", and may have been associated with the god Ishkur

Hadad ( uga, ), Haddad, Adad (Akkadian: 𒀭𒅎 '' DIM'', pronounced as ''Adād''), or Iškur ( Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions.

He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. ...

(Hadad). A slightly different lion-dragon with two horns and the tail of a scorpion appears in art from the Neo-Assyrian Period

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

(911 BC–609 BC). A relief probably commissioned by Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynas ...

shows the gods Ashur, Sin, and Adad standing on its back.

Another draconic creature with horns, the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird appears in Mesopotamian art from the Akkadian Period until the Hellenistic Period

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

(323 BC–31 BC). This creature, known in Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic ...

as the '' mušḫuššu'', meaning "furious serpent", was used as a symbol for particular deities and also as a general protective emblem. It seems to have originally been the attendant of the Underworld god Ninazu

Ninazu ( sux, ) was a Mesopotamian god of the underworld of Sumerian origin. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. He was frequently associated with Ereshkigal, either as a ...

, but later became the attendant to the Hurrian

The Hurrians (; cuneiform: ; transliteration: ''Ḫu-ur-ri''; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri or Hurriter) were a people of the Bronze Age Near East. They spoke a Hurrian language and lived in Anatolia, Syria and Norther ...

storm-god Tishpak

Tishpak (Tišpak) was a Mesopotamian god associated with the ancient city Eshnunna and its sphere of influence, located in the Diyala area of Iraq. He was primarily a war deity, but he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mus ...

, as well as, later, Ninazu's son Ningishzida

Ningishzida ( Sumerian: DNIN-G̃IŠ-ZID-DA, possible meaning "Lord f theGood Tree") was a Mesopotamian deity of vegetation, the underworld and sometimes war. He was commonly associated with snakes. Like Dumuzi, he was believed to spend a part ...

, the Babylonian national god

A national god is a guardian divinity whose special concern is the safety and well-being of an ethnic group (''nation''), and of that group's leaders. This is contrasted with other guardian figures such as family gods responsible for the well-be ...

Marduk

Marduk (Cuneiform: dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: ''amar utu.k'' "calf of the sun; solar calf"; ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of ...

, the scribal god Nabu

Nabu ( akk, cuneiform: 𒀭𒀝 Nabû syr, ܢܵܒܼܘܼ\ܢܒܼܘܿ\ܢܵܒܼܘܿ Nāvū or Nvō or Nāvō) is the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes, and wisdom.

Etymology and meaning

The Akkadian "n ...

, and the Assyrian national god Ashur.

Scholars disagree regarding the appearance of Tiamat

In Mesopotamian religion, Tiamat ( akk, or , grc, Θαλάττη, Thaláttē) is a primordial goddess of the sea, mating with Abzû, the god of the groundwater, to produce younger gods. She is the symbol of the chaos of primordial crea ...

, the Babylonian goddess personifying primeval chaos slain by Marduk in the Babylonian creation epic '' Enûma Eliš''. She was traditionally regarded by scholars as having had the form of a giant serpent, but several scholars have pointed out that this shape "cannot be imputed to Tiamat with certainty" and she seems to have at least sometimes been regarded as anthropomorphic. Nonetheless, in some texts, she seems to be described with horns, a tail, and a hide that no weapon can penetrate, all features which suggest she was conceived as some form of dragoness.

=Levant

= In the

In the Ugarit

)

, image =Ugarit Corbel.jpg

, image_size=300

, alt =

, caption = Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit

, map_type = Near East#Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size = 300

, relief=yes

, location = Latakia Governorate, Syria

, region = ...

ic Baal Cycle

The Baal Cycle is an Ugaritic cycle of stories about the Canaanite god Baʿal ( "Owner", "Lord"), a storm god associated with fertility. It is one of the Ugarit texts, dated to c. 1500-1300 BCE.

The text identifies Baal as the god Hadad, t ...

, the sea-dragon Lōtanu is described as "the twisting serpent / the powerful one with seven heads." In ''KTU'' 1.5 I 2–3, Lōtanu is slain by the storm-god Baal

Baal (), or Baal,; phn, , baʿl; hbo, , baʿal, ). ( ''baʿal'') was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied t ...

, but, in ''KTU'' 1.3 III 41–42, he is instead slain by the virgin warrior goddess Anat

Anat (, ), Anatu, classically Anath (; uga, 𐎓𐎐𐎚 ''ʿnt''; he, עֲנָת ''ʿĂnāṯ''; ; el, Αναθ, translit=Anath; Egyptian: '' ꜥntjt'') was a goddess associated with warfare and hunting, best known from the Ugaritic text ...

. In the Book of Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived ...

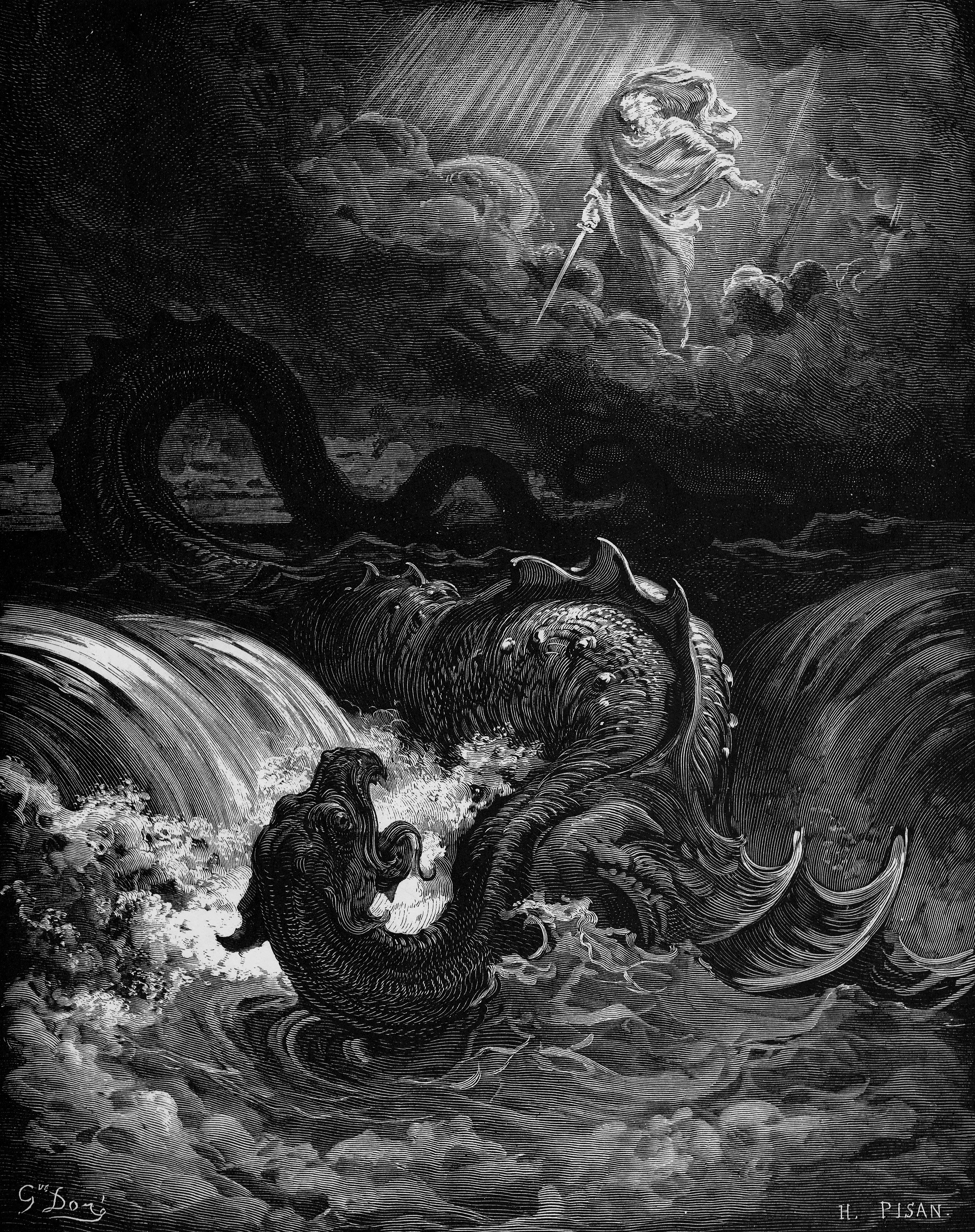

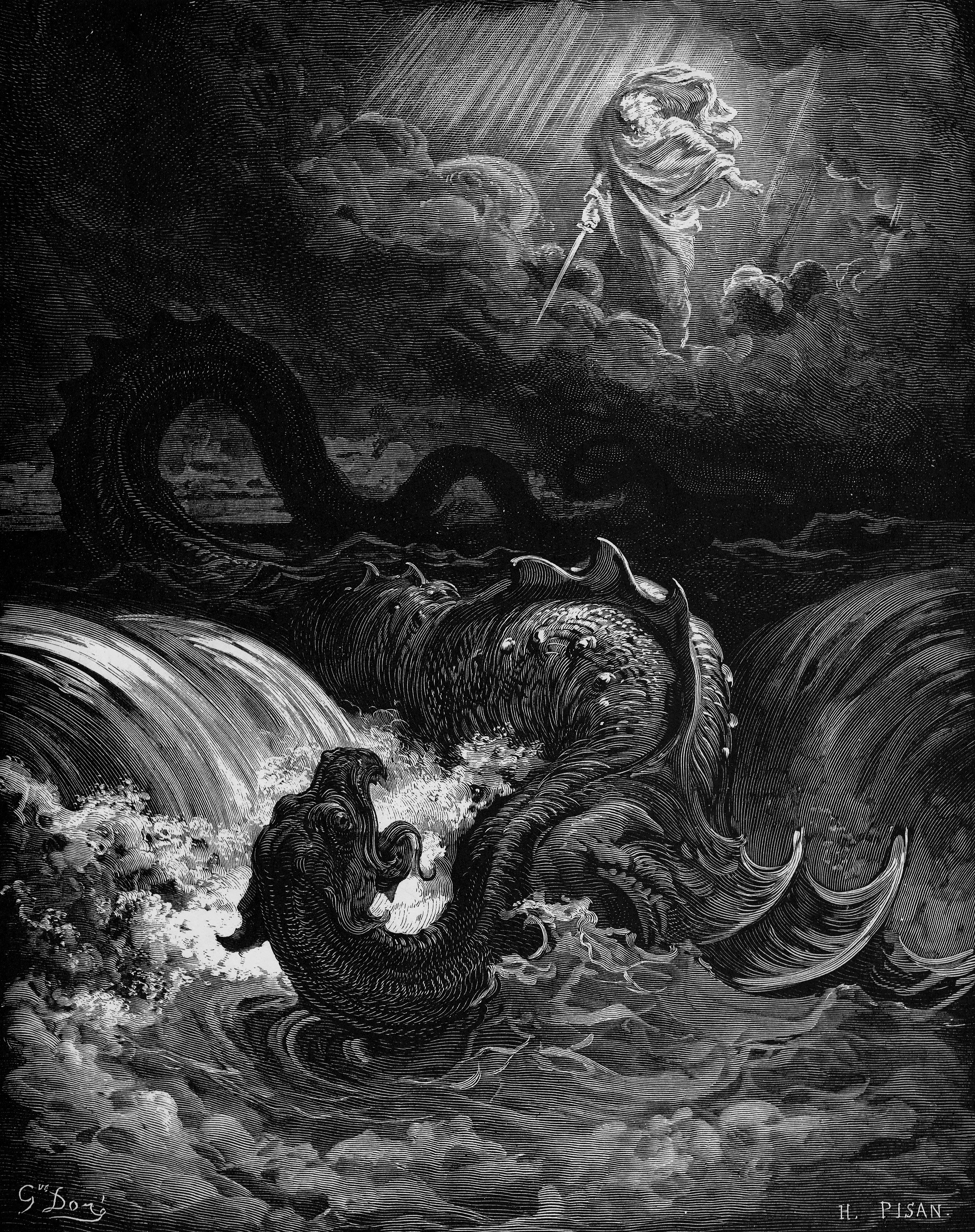

, Psalm 74, Psalm 74:13–14, the sea-dragon Leviathan

Leviathan (; he, לִוְיָתָן, ) is a sea serpent noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, the Book of Amos, and, according to some ...

, is slain by The LORD, God of the kingdoms of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Judah, as part of the creation of the world. In Isaiah 27:1, The LORD's destruction of Leviathan is foretold as part of The LORD's impending overhaul of the universal order:

Job 41:1–34 contains a detailed description of the Leviathan, who is described as being so powerful that only The LORD can overcome it. Job 41:19–21 states that the Leviathan exhales fire and smoke, making its identification as a mythical dragon clearly apparent. In some parts of the Old Testament, the Leviathan is historicized as a symbol for the nations that stand against The LORD. Rahab, a synonym for "Leviathan", is used in several Biblical passages in reference to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

. Isaiah 30:7 declares: "For Egypt's help is worthless and empty, therefore I have called her 'the silenced Rahab

Rahab (; Arabic: راحاب, a vast space of a land) was, according to the Book of Joshua, a woman who lived in Jericho in the Promised Land and assisted the Israelites in capturing the city by hiding two men who had been sent to scout the city ...

'." Similarly, Psalm 87:3 reads: "I reckon Rahab and Babylon as those that know me..." In Ezekiel 29:3–5 and Ezekiel 32:2–8, the pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

of Egypt is described as a "dragon" (''tannîn''). In the story of Bel and the Dragon

The narrative of Bel and the Dragon is incorporated as chapter 14 of the extended Book of Daniel. The original Septuagint text in Greek survives in a single manuscript, Codex Chisianus, while the standard text is due to Theodotion, the 2nd-cent ...

from the Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th century BC setting. Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon", it combines a prophecy of history with an eschatology (a ...

, the prophet Daniel

Daniel is a masculine given name and a surname of Hebrew origin. It means "God is my judge"Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 68. (cf. Gabriel—"God is my strength"), ...

sees a dragon being worshipped by the Babylonians. Daniel makes "cakes of pitch, fat, and hair"; the dragon eats them and bursts open.

Ancient and Post-classical

Iran/Persia

Azhi Dahaka (Avestan Great Snake) is a dragon or demonic figure in the texts and mythology of Zoroastrian Persia, where he is one of the subordinates of Angra Mainyu. Alternate names include Azi Dahak, Dahaka, Dahak. Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon. The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian azdahāg are the source of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed "Az", Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, Modern Persian 'aždehâ/aždahâ', Tajik Persian 'azhdahâ', Urdu 'azhdahā' (اژدها), as well as the Kurdish ejdîha (ئەژدیها). The name also migrated to Eastern Europe, assumed the form "azhdaja" and the meaning "dragon", "dragoness" or "water snake"in Balkanic and Slavic languages. Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples. TheAzhdarchid