Drag Boat on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A hydroplane (or hydro, or ''thunderboat'') is a fast

A hydroplane (or hydro, or ''thunderboat'') is a fast

A hydroplane (or hydro, or ''thunderboat'') is a fast

A hydroplane (or hydro, or ''thunderboat'') is a fast motorboat

A motorboat, speedboat or powerboat is a boat that is exclusively powered by an engine.

Some motorboats are fitted with inboard engines, others have an outboard motor installed on the rear, containing the internal combustion engine, the gea ...

, where the hull shape is such that at speed, the weight of the boat is supported by planing forces, rather than simple buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

.

A key aspect of hydroplanes is that they use the water they are on for lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

rather than buoyancy, as well as for propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived from ...

and steering

Steering is a system of components, linkages, and other parts that allows a driver to control the direction of the vehicle.

Introduction

The most conventional steering arrangement allows a driver to turn the front wheels of a vehicle using ...

: when travelling at high speed water is forced downwards by the bottom of the boat's hull. The water therefore exerts an equal and opposite force upwards, lifting the vast majority of the hull out of the water. This process, happening at the surface

A surface, as the term is most generally used, is the outermost or uppermost layer of a physical object or space. It is the portion or region of the object that can first be perceived by an observer using the senses of sight and touch, and is t ...

of the water, is known as ' foiling'.

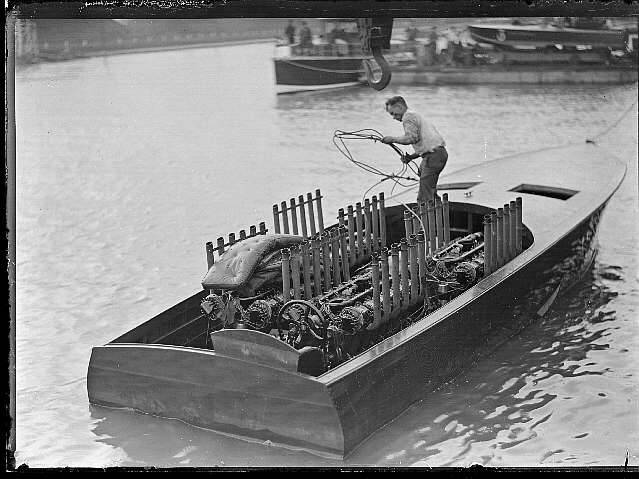

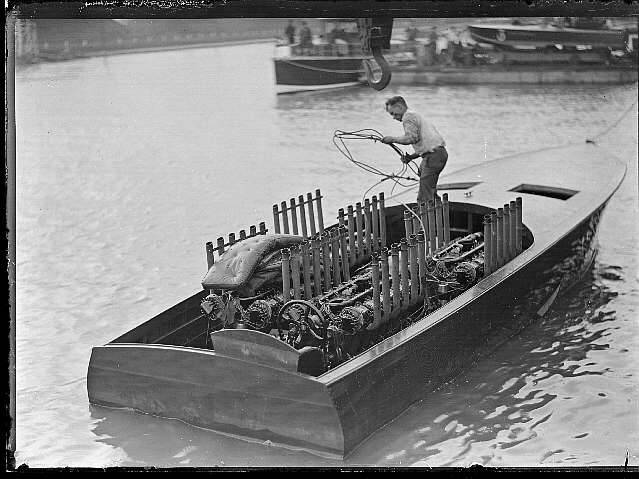

Hydroplane design

Early designs of the 1920s were often built by amateurs, who employed the lightest materials available to them at the time, which were often glued timber boarding or plywood on the floor, plywood topsides, and varnished canvas decks. Most were about long and stepped hulls were employed with a step to induce air under the hull, to enable the boat to float on air bubbles. The principle behind 'planing' was not fully understood. Thus, hulls were flat bottomed with an upward curve at the bow and the step of the way aft. The sheer weight of a 100 hp. engine was enough to keep the bow from digging in. In Ireland the sport was managed by the Motor Yacht Club of Ireland which had a base at theLough Ree Yacht Club

Lough Ree Yacht Club is a sailing club based in Ballglass, Coosan, near Athlone, Ireland. Founded in 1770, albeit under the name Athlone Yacht Club, it claims to be one of the oldest yacht clubs in the world, although another Irish yacht club, ...

near Athlone.

One of the earliest examples can be seen in the May 1935 ''Popular Mechanics

''Popular Mechanics'' (sometimes PM or PopMech) is a magazine of popular science and technology, featuring automotive, home, outdoor, electronics, science, do-it-yourself, and technology topics. Military topics, aviation and transportation o ...

'' issue. "Mile A Minute-Thrills of the Water" tells the story of the ''No-Vac'' by LeRoy F. Malrose Sr. aka. Fred W. McQuigg (pen name). Malrose was the lead design illustrator for ''Popular Mechanics'' magazine, which at the time was located in Chicago. The ''No-Vac'' design and build actually began in 1933, when Malrose conceptualized an airfoil hull surface design which proved to produce far less drag than conventional "V" style boat hull designs of the time. In June 1933 the ''No-Vac'' was put to the test with professional racing driver Jimmy Rodgers at the helm. That day the ''No-Vac'' set the world water speed record for an outboard powered boat of .

The basic hull design of most hydroplanes has remained relatively unchanged since the 1950s: two sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

s in front, one on each side of the bow; behind the wide bow, is a narrower, mostly rectangular section housing the driver, engine, and steering equipment. The aft part of the vessel is supported in the water by the lower half of the propeller, which is designed to operate semi-submerged at all times. The goal is to keep as little of the boat in contact with the water as possible, as water is much denser than air, exerting more drag on the vehicle. Essentially the boat 'flies' over the surface of the water rather than actually traveling through it.

One of the few significant attempts at a radically different design since the three-point propriding design was introduced was referred to as ''Canard''. It reversed the width properties, having a very narrow bow that only touched the water in one place, and two small outrigger

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts ...

sponsons in the back.

Early hydroplanes had mostly straight lines and flat surfaces aside from the uniformly curved bow and sponsons. The curved bow was eventually replaced by what is known as a ''pickle fork'' bow, where a space is left between the front few feet of the sponsons. Also, the centered single, vertical tail (similar to the ones on most modern airplanes) was gradually replaced by a horizontal stabilizer

A tailplane, also known as a horizontal stabiliser, is a small lifting surface located on the tail (empennage) behind the main lifting surfaces of a fixed-wing aircraft as well as other non-fixed-wing aircraft such as helicopters and gyroplan ...

supported by vertical tails on either side of the boat. Later, as fine-tuning the hydrodynamics

In physics and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids—liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including ''aerodynamics'' (the study of air and other gases in motion) and ...

became more important, the bottoms of the main hull have subtle curves to give the best lift.

Unlimited hydroplane engines

The aviation industry has been the main source of engines for the boats. For the first few decades after World War II, they used surplus World War II-erainternal-combustion

An internal combustion engine (ICE or IC engine) is a heat engine in which the combustion of a fuel occurs with an oxidizer (usually air) in a combustion chamber that is an integral part of the working fluid flow circuit. In an internal combus ...

airplane engines, typically Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

Merlins or Griffons

Griffon may refer to:

* Griffin, or griffon, a mythological creature with the body of a lion and head and wings of an eagle

Businesses

* Griffon Aerospace, an American aerospace and defense company

* Griffon Corporation, a multinational cong ...

, or Allison V-1710

The Allison V-1710 aircraft engine designed and produced by the Allison Engine Company was the only US-developed V-12 liquid-cooled engine to see service during World War II. Versions with a turbocharger gave excellent performance at high a ...

s, all liquid-cooled V-12s. The loud roar of these engines earned hydroplanes the nickname ''thunderboats'' or ''dinoboats''.

The Ted Jones-designed ''Slo-Mo-Shun IV'' three-point, Allison-powered hydroplane set the water speed record (160.323 mph) in Lake Washington

Lake Washington is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle.

It is the largest lake in King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington, after Lake Chelan. It borders the cities of Seattle on the west, ...

, off Seattle, Washington's Sand Point, on June 26, 1950, breaking the previous (ten-plus-year-old) record (141.740 mph/228.1 km/h) by almost 20 mph (32 km/h). Donald Campbell

Donald is a masculine given name derived from the Gaelic name ''Dòmhnall''.. This comes from the Proto-Celtic *''Dumno-ualos'' ("world-ruler" or "world-wielder"). The final -''d'' in ''Donald'' is partly derived from a misinterpretation of the ...

set seven world water speed records between 1955 and 1964 in the jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine discharging a fast-moving jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition can include rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and hybrid propulsion, the term ...

hydroplane, ''Bluebird

The bluebirds are a North American group of medium-sized, mostly insectivorous or omnivorous birds in the order of Passerines in the genus ''Sialia'' of the thrush family (Turdidae). Bluebirds are one of the few thrush genera in the Americas.

...

''.

Starting in 1980, they have increasingly used Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

-era turboshaft

A turboshaft engine is a form of gas turbine that is optimized to produce shaftpower rather than jet thrust. In concept, turboshaft engines are very similar to turbojets, with additional turbine expansion to extract heat energy from the exhaust ...

engines from helicopters (in 1973–1974, one hydroplane, ''U-95'', used turbine engines in races to test the technology). The most commonly used turbine is the Lycoming T55

The Honeywell T55 (formerly Lycoming; company designation LTC-4) is a turboshaft engine used on American helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft (in turboprop form) since the 1950s, and in unlimited hydroplanes since the 1980s. Today, there have b ...

, used in the CH-47 Chinook

The Boeing CH-47 Chinook is a tandem rotor helicopter developed by American rotorcraft company Piasecki Helicopter, Vertol and manufactured by Boeing Rotorcraft Systems#Background, Boeing Vertol. The Chinook is a heavy-lift helicopter that is a ...

.

Efforts have occasionally been made to use automotive engines, but they generally have not proven competitive.

The "limited" classes of inboard hydroplane racing

Hydroplane racing (also known as hydro racing) is a sport involving racing hydroplanes on lakes and rivers. It is a popular spectator sport in several countries.

Racing circuits

International professional outboard hydroplane racing

The Union Int ...

are organized under the name Inboard Powerboat Circuit. These classes utilize automotive power, as well as two-stroke power. There are races throughout the country from April to October. Many Unlimited drivers got their start in the "limited" classes.

Prior to 1977, every official water speed record had been set by an American, Briton, Irishman or Canadian. On November 20, Australian Ken Warby

Ken Warby (born 9 May 1939) is an Australian motorboat racer, who currently holds the water speed record of , set on Blowering Dam on 8 October 1978.

As a child, Warby's hero was Donald Campbell, who died attempting to break the record in 19 ...

piloted his '' Spirit of Australia'' purely on the jet thrust of its Westinghouse J34

The Westinghouse J34, company designation Westinghouse 24C, was a turbojet engine developed by Westinghouse Aviation Gas Turbine Division in the late 1940s. Essentially an enlarged version of the earlier Westinghouse J30, the J34 produced 3,000 p ...

turbojet to a velocity of 464.5 km/h (290.313 mph) to beat Lee Taylor's record. Warby, who had built the craft in his back yard, used the publicity to find sponsorship to pay for improvements to the ''Spirit''. On October 8, 1978 Warby travelled to Blowering Dam

The Blowering Dam is a major ungated rock fill with clay core embankment dam with concrete chute spillway impounding a reservoir under the same name. It is located on the Tumut River upstream of Tumut in the Snowy Mountains region of New Sou ...

, Australia, and broke both the 480 km/h (300 mph) and barriers with an average speed of 510 km/h (318.75 mph).

As of 2018, Warby's record still stands, and there have only been two official attempts to break it.

See also

*Hydrofoil

A hydrofoil is a lifting surface, or foil, that operates in water. They are similar in appearance and purpose to aerofoils used by aeroplanes. Boats that use hydrofoil technology are also simply termed hydrofoils. As a hydrofoil craft gains sp ...

, a different concept also applying lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

* Water speed record

References

External links

{{Authority control Racing motorboats Hydroplanes H1 UnlimitedRacing

In sport, racing is a competition of speed, in which competitors try to complete a given task in the shortest amount of time. Typically this involves traversing some distance, but it can be any other task involving speed to reach a specific goa ...

Racing