Donough MacCarty, 1st Earl of Clancarty on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Donough MacCarty, 1st Earl of Clancarty (1594–1665), was an Irish

/> but about 1638 his father had bought him a baronetcy of

/>

The Munster insurgents then attacked the castles of Sir

The Munster insurgents then attacked the castles of Sir

As the Confederates sent no troops to the King, their armies kept their full strength. The Munster Army, under Glamorgan, favoured by Rinuccini, was sent to besiege

As the Confederates sent no troops to the King, their armies kept their full strength. The Munster Army, under Glamorgan, favoured by Rinuccini, was sent to besiege

In April 1650, Muskerry lost Macroom Castle, where his family had been living. An Irish force raised by Fermoy and

In April 1650, Muskerry lost Macroom Castle, where his family had been living. An Irish force raised by Fermoy and

At the Restoration of the Stuarts, Clancarty, as he now was, returned to Ireland. He used Ormond's influence to recover his estates, which Charles II confirmed to him in his "Gracious Declaration" of 30 November 1660. The Cromwellian occupiers had to leave at once. Now-Admiral William Penn, to whom Macroom had been granted in 1654, was compensated with land at

At the Restoration of the Stuarts, Clancarty, as he now was, returned to Ireland. He used Ormond's influence to recover his estates, which Charles II confirmed to him in his "Gracious Declaration" of 30 November 1660. The Cromwellian occupiers had to leave at once. Now-Admiral William Penn, to whom Macroom had been granted in 1654, was compensated with land at

/> Charles left an infant son, called Charles James, who became the new heir apparent. Only one and a half months later, on 4 or 5 August 1665, Clancarty died at Ormond's house at Moor Park, Hertfordshire. Ormond, despite being a Protestant, called in a Catholic priest for the last rites of his friend. The Catholic political pamphlet ''The Unkinde Deserter of Loyall Men and True Frinds'' claims that in his last hour Clancarty expressed regret at having trusted Ormond. Charles's infant son Charles James succeeded his grandfather as the 2nd Earl of Clancarty but died a year later. The succession then reverted to the 1st Earl's second son, Callaghan, who succeeded as the 3rd Earl of Clancarty.

magnate

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

, soldier, and politician. He succeeded as 2nd Viscount Muskerry in 1641. He rebelled against the government, demanding religious freedom as a Catholic and defending the rights of the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

nobility in the Irish Catholic Confederation

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

. Later, he supported the King against his Parliamentarian enemies during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland w ...

, a part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, also known as the British Civil War.

He sat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

of the Irish parliaments of 1634–1635 and 1640–1649 where he opposed Strafford, King Charles I's authoritarian viceroy. In 1642 he sided with the Irish Rebellion when it reached his estates in Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following th ...

. He fought for the insurgents at the Siege of Limerick and the Battle of Liscarroll

The Battle of Liscarroll was fought on 3 September 1642 in northern County Cork, Munster, between Catholic Irish insurgents and government troops. The battle was part of the Irish Rebellion, which had started in the north in 1641 reac ...

. He joined the Irish Catholic Confederates and sat on their Supreme Council. Having fought in the Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Confederate Wars, also called the Eleven Years' War (from ga, Cogadh na hAon-déag mBliana), took place in Ireland between 1641 and 1653. It was the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, a series of civil wars in the kin ...

, he negotiated the Cessation of 1643, a cease-fire between the Confederates and the King. He tried to transform this cease-fire into a permanent peace and was the leader of the Confederates' peace party, which opposed the clerical faction led by Rinuccini Rinuccini is a surname, and may refer to:

*Giovanni Battista Rinuccini (1592–1653), an Italian archbishop.

*Ottavio Rinuccini

Ottavio Rinuccini (20 January 1562 – 28 March 1621) was an Italian poet, courtier, and opera librettist at the end of ...

, the papal nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international org ...

. Together with President Mountgarret, he negotiated the Glamorgan Peace in 1645, which was diavowed by the King. In 1646 he captured Bunratty Castle

Bunratty Castle (, meaning "castle at the mouth of the Ratty") is a large 15th-century tower house in County Clare, Ireland. It is located in the centre of Bunratty village ( ga, Bun Ráite), by the N18 road (Ireland), N18 road between Limerick ...

from the Parliamentarians and negotiated the First Ormond Peace, which was rejected by Rinuccini, who went so far as excommunicating

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose o ...

him. During the Cromwellian conquest, he lost the Battle of Knocknaclashy

The battle of Knocknaclashy (also known as Knockbrack), took place in County Cork in southern Ireland in 1651. In it, an Irish Confederate force led by Viscount Muskerry was defeated by an English Parliamentarian force under Lord Broghil ...

in 1651 but held on until 1652, defending Ross Castle

Ross Castle ( ga, Caisleán an Rois) is a 15th-century tower house and keep on the edge of Lough Leane, in Killarney National Park, County Kerry, Ireland. It is the ancestral home of the Chiefs of the Clan O'Donoghue, later associated w ...

. He was one of the last to surrender.

In 1653 during the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with " republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from th ...

he stood trial for war crimes but was acquitted. In exile on the continent, Charles II created him Earl of Clancarty

Earl of Clancarty is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Ireland.

History

The title was created for the first time in 1658 in favour of Donough MacCarty, 2nd Viscount Muskerry, of the MacCarthy of Muskerry dynasty. He had e ...

. He recovered his lands at the restoration of the monarchy

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

*Restoration ecology

...

in 1660.

Birth and origins

Donough MacCarty was born in 1594 inCounty Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns ar ...

, most likely at Blarney Castle

Blarney Castle ( ga, Caisleán na Blarnan) is a medieval stronghold in Blarney, near Cork, Ireland. Though earlier fortifications were built on the same spot, the current keep was built by the MacCarthy of Muskerry dynasty, a cadet branch of t ...

or Macroom Castle, residences of his parents. He was the second but eldest surviving son of Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

(alias Cormac Oge) MacCarthy and his first wife Margaret O'Brien. His father was at that time known as Sir Charles MacCarthy while his paternal grandfather, Cormac MacDermot MacCarthy, held the title as 16th Lord of Muskerry and owned the ancestral land covering large parts of central County Cork. His father's family were the MacCarthys of Muskerry

The MacCarthy dynasty of Muskerry is a tacksman branch of the MacCarthy Mor dynasty, the Kings of Desmond.

Origins and advancement

The MacCarthy of Muskerry are a cadet branch of the MacCarthy Mor, ...

, a Gaelic Irish

The Gaels ( ; ga, Na Gaeil ; gd, Na Gàidheil ; gv, Ny Gaeil ) are an ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man in the British Isles. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languag ...

dynasty that had branched from the MacCarthy-Mor line in the 14th century when a younger son received Muskerry

Muskerry ( ga, Múscraí) is a central region of County Cork, Ireland which incorporates the baronies of Muskerry West

as appanage

An appanage, or apanage (; french: apanage ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a sovereign, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture. It was common in much ...

.

Donough's mother was the eldest daughter of Donogh O'Brien, 4th Earl of Thomond. Donough was named for this grandfather (there were no Donoughs in the line of the MacCarthy of Muskerry). The name is an anglicised, shortened form of the Gaelic

Gaelic is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". As a noun it refers to the group of languages spoken by the Gaels, or to any one of the languages individually. Gaelic languages are spoken in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and Ca ...

first name Donnchadh Donnchadh () is a masculine given name common to the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages. It is composed of the elements ''donn'', meaning "brown" or "dark" from Donn a Gaelic God; and ''chadh'', meaning "chief" or "noble". The name is also writt ...

. Her family, the O'Briens

The O'Brien dynasty ( ga, label=Classical Irish, Ua Briain; ga, label=Modern Irish, Ó Briain ; genitive ''Uí Bhriain'' ) is a noble house of Munster, founded in the 10th century by Brian Boru of the Dál gCais (Dalcassians). After becomin ...

, were another Gaelic Irish dynasty that descended from Brian Boru

Brian Boru ( mga, Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig; modern ga, Brian Bóramha; 23 April 1014) was an Irish king who ended the domination of the High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill and probably ended Viking invasion/domination of Ireland. ...

, medieval high king of Ireland.

His parents had married about 1590. He was one of seven siblings (two brothers and five sisters), who are listed in his father's article.

Religion

Although most Irish remained Catholics under the Protestant monarchs Henry VIII and Queen Elizabeth, both of MacCarty's grandfathers were Protestants. His paternal grandfather, Cormac MacDermot MacCarthy, had conformed to theestablished religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a ...

. MacCarty's maternal grandfather, Donogh O'Brien, 4th Earl of Thomond, had been brought up as Protestant at the English court. MacCarty's father seems to have been a protestant in his youth but later became Catholic.

Early life, marriage, and children

When MacCarty's mother died, his father remarried to Ellen Roche, who therefore became his stepmother. She was the eldest daughter ofDavid Roche, 7th Viscount Fermoy

David Roche, 7th Viscount Fermoy (1573–1635) was an Irish magnate, soldier, and politician.

Birth and origins

David was born about 1573, probably in Castletownroche, County Cork, Ireland. He was the only surviving son of Maurice Roche and ...

and widow of Donnell MacCarthy Reagh. The date of the marriage is disputed. It seems that Ellen's first husband was Donal MacCarthy Reagh of Kilbrittain

Donal MacCarthy Reagh of Kilbrittain (died 1636) was an Irish magnate who owned the extensive lands of Carbery (almost half a million acres) in south-western County Cork.

Birth and origins

Donal was born the son of Cormac MacCarthy Reagh a ...

, that she had a son Charles (also called Cormac) with Donal, and that Donal died in 1636. However, Jane Ohlmeyer

Jane Ohlmeyer, , is a historian and academic, specialising in early modern Irish and British history. She is the Erasmus Smith's Professor of Modern History (1762) at Trinity College Dublin and Chair of the Irish Research Council, which funds ...

gives 1599 as date of the marriage, more than 30 years earlier.

None of the cited works mention children from this marriage. His stepmother's father was a zealous Catholic but a loyal supporter of the government.

In 1616 MacCarty's father succeeded as the 17th Lord of Muskerry. In 1628 King Charles I created MacCarty's father Baron Blarney and Viscount Muskerry. The titles were probably purchased. They had a special remainder

In mathematics, the remainder is the amount "left over" after performing some computation. In arithmetic, the remainder is the integer "left over" after dividing one integer by another to produce an integer quotient (integer division). In algeb ...

that designated Donough as successor, excluding his elder brother, who was alive at the time but probably had an intellectual disability

Intellectual disability (ID), also known as general learning disability in the United Kingdom and formerly mental retardation, Rosa's Law, Pub. L. 111-256124 Stat. 2643(2010). is a generalized neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by signif ...

.

MacCarty married Eleanor Butler some time before 1633 as their eldest son was born in 1633 or 1634. She was a Catholic, the eldest daughter of Thomas Butler, Viscount Thurles

Thomas Butler, Viscount Thurles (before 1596 – 1619) was the son and heir apparent of Walter Butler, 11th Earl of Ormond (1559 – 1633), whom he predeceased. He lived at the Westgate Castle in Thurles, County Tipperary. He was the father o ...

. The Butlers were an Old English family descending from Theobald Walter

Theobald Walter (sometimes Theobald FitzWalter, Theobald Butler, or Theobald Walter le Boteler) was the first Chief Butler of Ireland. He also held the office of Chief Butler of England and was the High Sheriff of Lancashire for 1194. Theobald ...

, who came to Ireland during the reign of King Henry II. MacCarty was already in his late thirties while she was about twenty. He had been married before and had a son Donall from this wife, but this earlier marriage seems to have been ignored by his family. His marriage to Eleanor made him a brother-in-law of James Butler, who succeeded as 12th Earl of Ormond in 1633, just before or just after MacCarty's marriage. Ormond was a Protestant, as he had been brought up in England as a ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a priso ...

under the care of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Donough and Eleanor had three sons:

#Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was ...

(1633 or 1634–1665), also called Cormac, predeceased his father, being slain at sea in the Battle of Lowestoft

The Battle of Lowestoft took place on during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. A fleet of more than a hundred ships of the United Provinces commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Jacob van Wassenaer, Lord Obdam attacked an English fleet of equal size comm ...

# Callaghan (died 1676), succeeded his elder brother's infant son, Charles James, as the 3rd Earl of Clancarty

#Justin

Justin may refer to: People

* Justin (name), including a list of persons with the given name Justin

* Justin (historian), a Latin historian who lived under the Roman Empire

* Justin I (c. 450–527), or ''Flavius Iustinius Augustus'', Eastern Rom ...

( – 1694), fought for the Jacobites and became Viscount Mountcashel

—and two daughters:

# Helen (died 1722), became Countess of Clanricarde

Clanricarde (; ), also known as Mac William Uachtar (Upper Mac William) or the Galway Burkes, were a fully Gaelicised branch of the Hiberno-Norman House of Burgh who were important landowners in Ireland from the 13th to the 20th centuries.

Te ...

. She married first Sir John FitzGerald of Dromana

Sir John FitzGerald of Dromana ( – 1662 or 1664) was the last of the FitzGeralds of Dromana. He sat as MP for Dungarvan in the Irish Parliament of 1661–1666.

Birth and origins

John was born about 1635 probab ...

and secondly William Burke, 7th Earl of Clanricarde

William Burke, 7th Earl of Clanricarde, PC (Ire) (; ; died 1687), was an Irish peer who fought in his youth together with his brother Richard, 6th Earl of Clanricarde under their cousin, Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde against the P ...

.

#Margaret (died 1704), became Countess of Fingall by marrying Luke Plunket, 3rd Earl of Fingall

House of Commons

When Charles I summoned the Irish Parliament of 1634–1635, MacCarty, already in his forties, stood forCork County

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

and was elected as one of its two "knights of the shire

Knight of the shire ( la, milites comitatus) was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistributio ...

" as county MPs were then called. He had been knighted in 1634. The Lord Deputy of Ireland, Thomas Wentworth (the future Lord Strafford) asked to vote taxes: six subsidies of £50,000 (equivalent to about £ in ) were passed unanimously. The parliament also belatedly and incompletely ratified the Graces of 1628, in which the King conceded rights for money.

MacCarty was re-elected for Cork County to the Irish Parliament of 1640–1649. The parliamentary records list him as a knight,609/> but about 1638 his father had bought him a baronetcy of

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native En ...

. The King sold these for 3,000 merk Scots

The merk is a long-obsolete Scottish silver coin. Originally the same word as a money mark

Mark Ramos Nishita (born February 10, 1960), known professionally as Money Mark, is an American producer and musician, best known for his collaborati ...

each or £166 13s. 4d. sterling (equivalent to about £ in ). Under Strafford's guidance, the parliament unanimously voted four subsidies of £45,000 (equivalent to about £ in ) to raise an Irish army of 9,000 for use against the Scots in the Second Bishops' War

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds eac ...

.

In April Strafford left Ireland to advise the King during the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on the 20th of February 1640 and sat from 13th of April to the 5th of May 1640. It was so called because of its short life of only three weeks.

Af ...

at Westminster. The Irish Commons saw their chance to complain about Strafford's authoritarian regime. They formed a committee for grievances of which MacCarty was a member. The committee prepared a remonstrance, called the November Petition, which was signed by all its members. The petition was then voted and approved by the Commons. MacCarty also was part of the delegation of 13 MPs that went to London in November to submit the petition to the King. The Lords sent a separate delegation for their grievances. MacCarty's father was part of it.244/>

Viscount Muskerry

In February 1641, MacCarty's father, aged about 70, died in London during his parliamentary mission. He was buried inWestminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. MacCarty succeeded as 2nd Viscount Muskerry. He lost his seat in the Commons where he was replaced by Redmond Roche

Redmond Roche ( – after 1654) was an Irish politician who sat for Cork County in the Parliament of 1640–1649. He was a Protestant during his earlier life but joined the Confederateses in 1642.

Birth and origins

...

, an uncle by his stepmother. As his ailing elder brother had died some time before, the title's special remainder did not need to be invoked. In March when Strafford was tried by the English House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster ...

, Muskerry gave evidence that Strafford had prevented Irish people from seeing the King. When he came back to Dublin, Muskerry took his seat in the Irish House of Lords

The Irish House of Lords was the upper house of the Parliament of Ireland that existed from medieval times until 1800. It was also the final court of appeal of the Kingdom of Ireland.

It was modelled on the House of Lords of England, with mem ...

.

Irish wars

Ireland suffered 11 years of war from 1641 to 1652, which can be divided into theRebellion of 1641

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1641) was an uprising by Irish Catholics in the Kingdom of Ireland, who wanted an end to anti-Catholic discrimination, greater Irish self-governance, and to partially or fully reverse the plantatio ...

, the Confederate Wars, and the Cromwellian Conquest. This Eleven Year War in turn forms part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, also known as the British Civil Wars.

Rebellion

Seeing the King weak and trying to opposeplantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

, Sir Phelim O'Neill

Sir Phelim Roe O'Neill of Kinard ( Irish: ''Sir Féilim Rua Ó Néill na Ceann Ard''; 1604–1653) was an Irish politician and soldier who started the Irish rebellion in Ulster on 23 October 1641. He joined the Irish Catholic Confedera ...

launched the Rebellion from the northern province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label=Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kin ...

in October 1641. He pretended, in his Proclamation of Dungannon

The Proclamation of Dungannon was a document produced by Sir Phelim O'Neill on 24 October 1641 in the Irish town of Dungannon. O'Neill was one of the leaders of the Irish Rebellion which had been launched the previous day. O'Neill's Proclamati ...

, to have a royal commission sanctioning his actions. In Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following th ...

Muskerry socialised with Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork

Richard Boyle, 1st Earl of Cork (13 October 1566 – 15 September 1643), also known as the Great Earl of Cork, was an English politician who served as Lord Treasurer of the Kingdom of Ireland.

Lord Cork was an important figure in the continuing ...

, an English Protestant established in Ireland, with whom he had opposed Strafford. News of the rebellion reached Lord Cork at a dinner at Castlelyons

Castlelyons () is a small village in the east of County Cork, Ireland. It is also a civil parish in the barony of Barrymore.

where David Barry, 1st Earl of Barrymore

David Barry, 1st Earl of Barrymore, 19th Baron Barry, 6th Viscount Buttevant (1605–1642) was an Irish peer.

Birth and Origins

David was born on 10 March 1605 probably at Buttevant, County Cork, a posthumous child of David de Barry and h ...

entertained Muskerry and Cork's son Roger, Lord Broghill. Barrymore was an Irish Protestant and Cork's son-in-law. Muskerry would later oppose Barrymore and Broghill in battle, but in February 1642 Muskerry still sided with Sir William St Leger, Lord President of Munster

The post of Lord President of Munster was the most important office in the English government of the Irish province of Munster from its introduction in the Elizabethan era for a century, to 1672, a period including the Desmond Rebellions in Munste ...

, against the insurgents. Muskerry offered to raise an armed force of his tenants and dependants to maintain law and order. He and his wife tried to save Protestants fleeing from the insurgents. In January 1642 the Munster insurgents under Maurice Roche, 8th Viscount Fermoy besieged Lord Cork in Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long and narrow layout. ...

.

However, the rebellion was gaining ground, and on 2 March, Muskerry changed sides, to defend the Catholic faith and the King as he explained on 17 March in a letter to Barrymore. Muskerry believed Phelim O'Neill acted under a royal warrant, but the King had already denounced the Irish insurgents as traitors in January. Hearing of his defection, the Irish Parliament declared Muskerry's estates forfeit

Forfeit or forfeiture may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Forfeit'', a 2007 thriller film starring Billy Burke

* "Forfeit", a song by Chevelle from '' Wonder What's Next''

* '' Forfeit/Fortune'', a 2008 album by Crooked Fingers

...

. He lost the Dublin townhouse that his father had built about 1640, but the government could not seize his Munster estates.

Like many Catholic royalists, Muskerry imagined Charles could be convinced to accept Catholicism in Ireland as he accepted Presbyterianism in Scotland. He was also prompted to take up arms by the atrocities committed by William St Leger

Sir William St Leger PC (Ire) (1586–1642) was an Anglo-Irish landowner, administrator and soldier, who began his military career in the Eighty Years' War against Habsburg Spain. He settled in Ireland in 1624, where he was MP for Cork Count ...

against the Catholic population and by the approach of Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret

Richard Butler, 3rd Viscount Mountgarret (1578–1651) was the son of Edmund Butler, 2nd Viscount Mountgarret and Grany or Grizzel, daughter of Barnaby Fitzpatrick, 1st Baron Upper Ossory. He is best known for his participation in the Irish Confede ...

with his rebel army. Muskerry refused to serve under Mountgarret and competed for the leadership in Munster with Fermoy, an uncle by his stepmother. Fermoy had led the rebellion in Munster before Muskerry joined and outclassed him in terms of precedence

Precedence may refer to:

* Message precedence of military communications traffic

* Order of precedence, the ceremonial hierarchy within a nation or state

* Order of operations, in mathematics and computer programming

* Precedence Entertainment, a ...

, but Muskerry was richer. At a meeting of the leaders at Blarney, Garret Barry, a veteran of the Spanish Army of Flanders

The Army of Flanders ( es, Ejército de Flandes nl, Leger van Vlaanderen) was a multinational army in the service of the kings of Spain that was based in the Spanish Netherlands during the 16th to 18th centuries. It was notable for being the long ...

, was made general of the Munster insurgents' army as a compromise. Muskerry was his second-in-command.

In March and April, Muskerry and Fermoy with 4,000 men unsuccessfully besieged St Leger in Cork City. On 13 April Murrough O'Brien, 6th Baron Inchiquin, an Irish Protestant, lifted the siege by driving the insurgents from their base at Rochfordstown. Muskerry lost his armour, tent, and trunks in this action. He and his lady stayed nearby at Blarney Castle at the time. On 16 May, Muskerry and Fermoy captured Barrymore Castle at Castlelyons, Barrymore's seat. St Leger died on 2 July, and Inchiquin, the vice-president, took over the command of the government forces in Munster.

Siege of Limerick

In May and June 1642, Muskerry, Garret Barry, Patrick Purcell of Croagh, and Fermoy attacked Limerick. The town opened its gates willingly, but the Protestants defended King John's Castle in the Siege of Limerick. They were led by George Courtenay, 1st Baronet, of Newcastle, who was the constable of Limerick Castle. Muskerry had a cannon placed on the tower of St Mary's Cathedral, which overlooked the castle. The besiegers attacked the castle's eastern wall and thebastion

A bastion or bulwark is a structure projecting outward from the curtain wall of a fortification, most commonly angular in shape and positioned at the corners of the fort. The fully developed bastion consists of two faces and two flanks, with fi ...

on its south-east corner by digging mines. The castle surrendered on 21 June and Muskerry took possession. The insurgents had already attacked castles in the Connello area west of Limerick, which had been settled with English during the Plantation of Munster

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, angl ...

. On 26 March Patrick Purcell had laid siege to Castletown, defended by Hardress Waller

Sir Hardress Waller (1666), was an English Protestant who settled in Ireland and fought for Parliament in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A leading member of the radical element within the New Model Army, he signed the death warrant for the Exe ...

, the future Cromwellian general. The castle fell in May. In July, Muskerry and Patrick Purcell used artillery, captured at King John's Castle, to take Kilfinny, defended by Elizabeth Dowdall

Elizabeth Dowdall ( Southwell); – after 1642) was a member of the Irish gentry, famed for having defended Kilfinny Castle, County Limerick, against the insurgents during the Irish Rebellion of 1641.

Birth and background

Elizabeth was born ...

, Waller's mother-in-law.

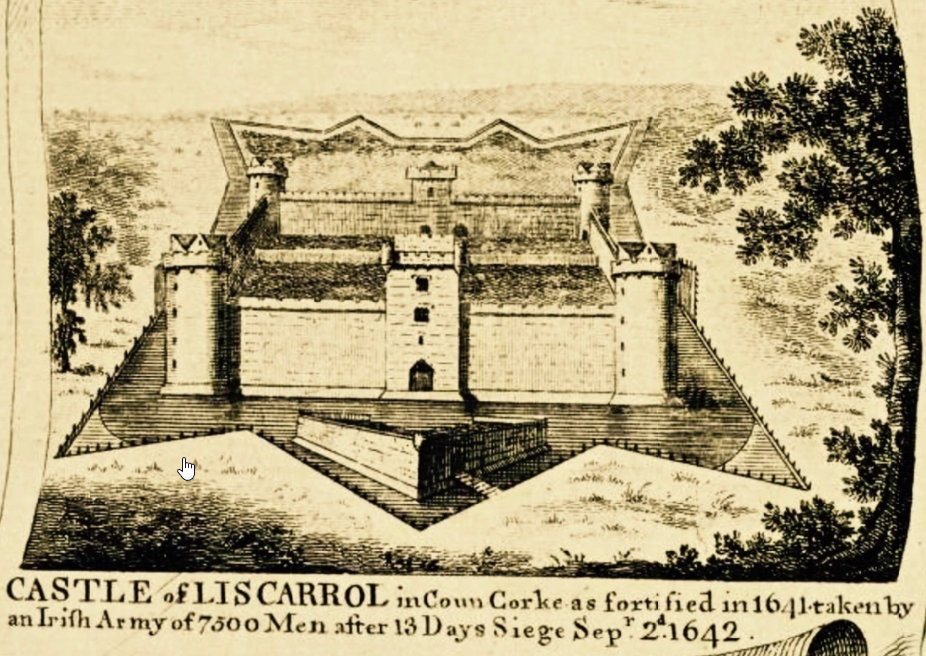

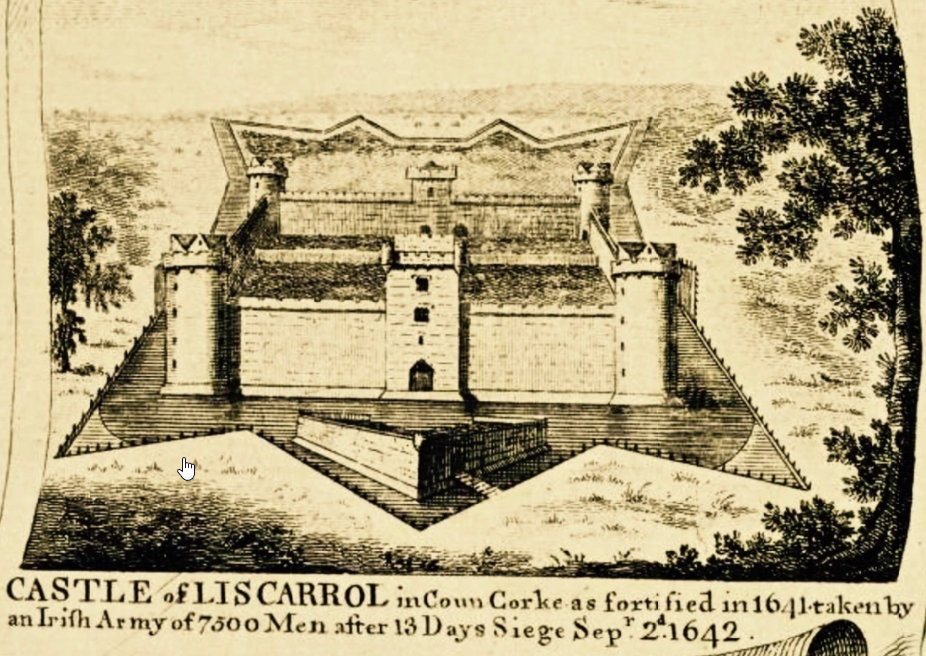

Siege and Battle of Liscarroll

The Munster insurgents then attacked the castles of Sir

The Munster insurgents then attacked the castles of Sir Philip Perceval

Sir Philip Perceval (1605 – 10 November 1647) was an English politician and knight. He was knighted in 1638, obtained grants of forfeited lands in Ireland to the amount of , and lost extensive property in Ireland owing to the rebellion of 164 ...

. In the summer of 1642 Muskerry took Annagh Castle, County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region. The county is named afte ...

, and in August besieged Liscarroll Castle, County Cork. The castle surrendered on 2 September. The next day Inchiquin with his army appeared before the castle. Despite inferior numbers Inchiquin defeated the insurgents under General Garret Barry in the ensuing Battle of Liscarroll

The Battle of Liscarroll was fought on 3 September 1642 in northern County Cork, Munster, between Catholic Irish insurgents and government troops. The battle was part of the Irish Rebellion, which had started in the north in 1641 reac ...

. Muskerry allegedly panicked, fled, and caused others to flee. His Protestant acquaintance Barrymore died in September, supposedly of wounds received in the battle.

Confederation

In 1642 the insurgents organised themselves in theIrish Catholic Confederation

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

. In May the Catholic Church declared the war lawful. An oath of association was dawn up. In October Muskerry attended the first Confederate General Assembly at Kilkenny where Mountgarret was elected president of the Confederation. Muskerry was not elected to the Supreme Council, but his rival Fermoy was. Garret Barry was made general of the Munster Army, despite his recent defeat and advanced age. Barry seems to have held the position until his death in March 1646 in Limerick, but others commanded in his stead. In 1643 Muskerry and Fermoy were both elected to the Supreme Council.

Muskerry commanded the infantry at the Battle of Cloughleagh

The Battle of Cloghleagh, Cloghlea, Cloughleagh, Cloughleigh also known as the Battle of Funcheon Ford or the Battle of Manning Water, was a battle fought between a Royalist force and an Irish Confederate force during the Irish Confederate ...

on 4 June 1643 where the Irish cavalry under James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven

James Tuchet, 3rd Earl of Castlehaven ( - 11 October 1684) was the son of Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven and his first wife, Elizabeth Barnham (1592 - ). Castlehaven played a prominent role in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms that took pl ...

, routed a detachment of Inchiquin's troops under Sir Charles Vavasour, 1st Baronet, of Killingthorpe, who had taken the Cloughleagh Tower House near Fermoy

Fermoy () is a town on the River Blackwater in east County Cork, Ireland. As of the 2016 census, the town and environs had a population of approximately 6,500 people. It is located in the barony of Condons and Clangibbon, and is in the D� ...

the day before. Muskerry with the infantry arrived only after the decisive cavalry charge. Castlehaven considered him slow and called him "the old general".

Later that year, Muskerry led the Munster Army in an offensive against Inchiquin in County Waterford

County Waterford ( ga, Contae Phort Láirge) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and is part of the South-East Region. It is named after the city of Waterford. Waterford City and County Council is the local authority for ...

. Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

, Patrick Purcell, unsuccessfully besieged Lismore Castle

Lismore Castle ( ga, Caisleán an Lios Mhóir) is a castle located in the town of Lismore, County Waterford, Lismore, County Waterford in the Republic of Ireland. It belonged to the Earl of Desmond, Earls of Desmond, and subsequently to the Caven ...

, the seat of the Earls of Cork

Earl of Cork is a title in the Peerage of Ireland, held in conjunction with the Earldom of Orrery since 1753. It was created in 1620 for Richard Boyle, 1st Baron Boyle. He had already been created Lord Boyle, Baron of Youghal, in the County ...

. Muskerry was about to take Cappoquin

Cappoquin, also spelt Cappaquin or Capaquin (), is a town in west County Waterford, Ireland. It is on the Blackwater river at the junction of the N72 national secondary road and the R669 regional road. It is positioned on a sharp 90-degree ben ...

but engaged in parley

A parley (from french: link=no, parler – "to speak") refers to a discussion or conference, especially one designed to end an argument or hostilities between two groups of people. The term can be used in both past and present tense; in pre ...

s and was outwitted by Inchiquin, who delayed the town's surrender until September when the cease-fire ended the war.

Cessation and Oxford conference

Muskerry, like most of themagnates

The magnate term, from the late Latin ''magnas'', a great man, itself from Latin ''magnus'', "great", means a man from the higher nobility, a man who belongs to the high office-holders, or a man in a high social position, by birth, wealth or ot ...

among the Confederates, was afraid to lose title and land when the King regained control. He therefore adhered to a faction within the Confederates, called the peace party or the Ormondists, that sought an agreement that would protect against such a loss. The King, on the other hand, sought peace with the Confederates to be able to withdraw troops from Ireland for use in the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians ("Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of Kingdom of England, England's governanc ...

. In 1643, the King asked Ormond to open talks with the Confederates. On 15 September 1643 at Sigginstown, Strafford's unfinished house, the Confederates signed a cease-fire with Ormond, called the "Cessation". Muskerry was one of the signatories. The Confederates agreed to pay the King £30,000 (equivalent to about £ in ) in several instalments. In return, the Confederates gained some degree of diplomatic recognition. The articles of the Cessation gave Lismore Castle and Cappoquin to Inchiquin.

In November 1643 the Supreme Council appointed seven delegates, with Muskerry as leader, to submit grievances to the King and negotiate a peace treaty. In January 1644 they obtained safe-conduct

Safe conduct, safe passage, or letters of transit, is the situation in time of international conflict or war where one state, a party to such conflict, issues to a person (usually an enemy state's subject) a pass or document to allow the enemy ...

s from the Lords Justices. It must have been their last days in office as Ormond was sworn-in as lord lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the King ...

on 21 January. The delegates arrived on 24 March at Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

where the King held his court. Muskerry demanded public exercise of the Catholic religion, independence from the English parliament, and full amnesty for their rebellion. The King offered Muskerry an earldom, which he refused. A competing Irish Protestant delegation arrived on 17 April. End of June the Confederate delegates returned to Ireland empty-handed.

The Cessation allowed the Confederates to focus on their war with the Covenanters

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covenan ...

in Ulster, who were aligned with the English Parliament. Owen Roe O'Neill

Owen Roe O'Neill ( Irish: ''Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill;'' – 1649) was a Gaelic Irish soldier and one of the most famous of the O'Neill dynasty of Ulster. O'Neill left Ireland at a young age and spent most of his life as a mercenary in the Spanish ...

led the Confederate Ulster army, deployed on that front, but the Supreme Council imposed Castlehaven as general-in-chief for the campaign of 1644. Castlehaven marched north to Charlemont but did not bring the Covenanters to battle. In July Inchiquin declared for Parliament, reactivating the southern front around the city of Cork, where the Munster Army was deployed. The fourth general assembly, in July 1644, elected the fourth Supreme Council. Muskerry regained his seat, but Fermoy did not. The cessation had a duration of one year, expiring on 15 September 1644. It was extended twice:

by Muskerry and Ormond in August 1644 until 1 December; and by Muskerry and Lord Chancellor Bolton

Bolton (, locally ) is a large town in Greater Manchester in North West England, formerly a part of Lancashire. A former mill town, Bolton has been a production centre for textiles since Flemish weavers settled in the area in the 14th ce ...

in September until 31 January 1645.

In the campaign of 1645, Castlehaven commanded the Munster Army in its fight against Inchiquin. Under Castlehaven's command Patrick Purcell took Lismore Castle, but Inchiquin doggedly defended the rest. In the fifth general assembly in summer 1645, Muskerry was re-elected to the Supreme Council.

Glamorgan Treaty

In 1645 the King sent Edward Somerset, Earl of Glamorgan, to Ireland to speed up the peace negotiations with the Confederates. Glamorgan was an English Catholic and son ofHenry Somerset, 1st Marquess of Worcester

Henry may refer to:

People

* Henry (given name)

* Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal ...

, an important royalist. Ormond sent Glamorgan to Kilkenny with a letter of introduction to Muskerry dated 11 August. He was received by Mountgarret and Muskerry. On 25 August Glamorgan signed the first Glamorgan Treaty with the Confederates. Muskerry was one of the signatories. The treaty was kept secret. It ceded to the Catholics the churches that the Confederates had seized since the beginning of the rebellion. Sir Charles Coote divulged it in October after he found a copy in the luggage of Malachy Queally, bishop of Tuam, killed in action near Sligo. The King disavowed the treaty in January 1646.

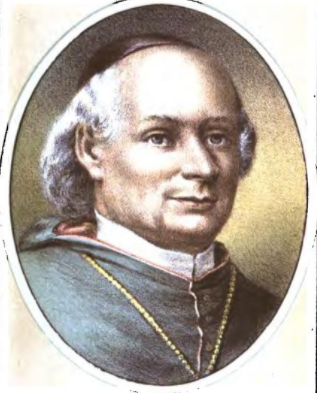

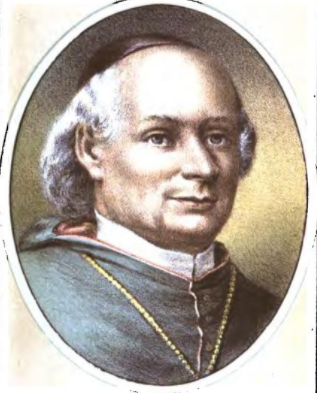

Nuncio

In 1645 the pope sentGiovanni Battista Rinuccini

Giovanni Battista Rinuccini (1592–1653) was an Italian Roman Catholic archbishop in the mid-seventeenth century. He was a noted legal scholar and became chamberlain to Pope Gregory XV. In 1625 Pope Urban VIII made him the Archbishop of Ferm ...

as nuncio to the Irish Catholic Confederation. Rinuccini landed in October on Ireland's south-west coast with money and weapons. On his way to Kilkenny, the Confederate capital, Rinuccini visited Macroom Castle where Lady Muskerry and her 11-year-old eldest son, Charles, received him while her husband was negotiating with Ormond in Dublin. The nuncio stayed for four days and then continued to Kilkenny arriving on 12 November.

In town, the nuncio was attended to by Muskerry, who had just returned from Dublin, and by General Preston. They accompanied him to Kilkenny Castle

Kilkenny Castle ( ga, Caisleán Chill Chainnigh, IPA: �kaʃlʲaːnˠˈçiːl̪ʲˈxan̪ʲiː is a castle in Kilkenny, Ireland built in 1195 to control a fording-point of the River Nore and the junction of several routeways. It was a symbol o ...

for his official reception by Mountgarret and escorted him back to his residence.

First Ormond Peace

The Confederate assembly on 6 March 1646 authorised its delegates to conclude a peace with Ormond. Muskerry signed the "First Ormond Peace" on 28 March 1646 for the Confederates. The treaty's 30 articles covered civil rights, but left the religious ones to be decided by a future Irish parliament. The parties agreed to defer the treaty's publication for now. According to the treaty, the Confederates were expected to send an Irish army of 10,000 men, about half the Confederate army, to England before 1 May, but by then it was already too late.Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city i ...

had fallen in September 1645 and Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

in February 1646, depriving the King of his main harbours on the Irish sea. Admiral Richard Swanley

Richard Swanley (died September 1650) was a British Royal Navy commander.

Biography

Swanley is probably to be identified with the Richard Swanley, a commander in the East India Company's service, who in 1623 went out as master of the Great Jame ...

and Captain William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy an ...

patrolled the sea with the Irish Squadron

The Irish Squadron originally known as the Irish Fleet was a series of temporary naval formations assembled for specific military campaigns of the English Navy, the Navy Royal and later the Royal Navy from 1297 to 1731.

History

From the 13t ...

of the Parliamentarian Navy. Muskerry wrote to Ormond on 3 April that the Irish army's expedition to England had to be abandoned. The First English Civil War ended shortly after the First Ormond Peace was signed. The Scots took the King into custody on 5 May.

Siege of Bunratty

As the Confederates sent no troops to the King, their armies kept their full strength. The Munster Army, under Glamorgan, favoured by Rinuccini, was sent to besiege

As the Confederates sent no troops to the King, their armies kept their full strength. The Munster Army, under Glamorgan, favoured by Rinuccini, was sent to besiege Bunratty Castle

Bunratty Castle (, meaning "castle at the mouth of the Ratty") is a large 15th-century tower house in County Clare, Ireland. It is located in the centre of Bunratty village ( ga, Bun Ráite), by the N18 road (Ireland), N18 road between Limerick ...

near Limerick, into which the 6th Earl of Thomond, a Protestant, had admitted a Parliamentarian garrison in March 1646. The Confederates lacked money to pay their army. After a setback on 1 April, in which the garrison drove the besiegers from their camp at Sixmilebridge

Sixmilebridge (), is a large village in County Clare, Ireland. Located midway between Ennis and Limerick city, the village is a short distance away from the main N18 road.

Sixmilebridge partly serves as a dormitory village for workers in the ...

, the Supreme Council replaced Glamorgan with Muskerry at the end of May. Muskerry had Lieutenant-General Purcell, Major-General Stephenson, and Colonel Purcell under him with three Leinster regiments and all the Munster forces. The castle's defences had been modernised by surrounding the castle proper, essentially a big tower house, with modern earthworks and forts defended by cannons. These fortifications abutted on the sea and Bunratty was supported by a small squadron of the Parliamentarian Navy under now-Vice-Admiral Penn. On 9 May, Lord Thomond left Bunratty for England by sea. On 13 June arrived the news of Owen Roe O'Neill's victory over the Covenanters at Benburb

Benburb ()) is a village and townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It lies 7.5 miles from Armagh and 8 miles from Dungannon. The River Blackwater runs alongside the village as does the Ulster Canal.

History

It is best known, in his ...

, won with the financial support from the nuncio. At the end of June Rinuccini came and paid the soldiers £600 (equivalent of about £ in ), exhausting the last of his funds. Muskerry brought two heavy cannons from Limerick for the siege. His rivals accused him of having spared the castle because Thomond was his uncle. When on 1 July a chance shot through a window killed McAdam, the Parliamentarian commander, Muskerry pressed on and the castle capitulated on 14 July. The garrison was evacuated to Cork by the Parliamentarian Navy, but had to leave arms, ammunition, and provisions behind.

Early in 1646, while Muskerry was at the siege of Bunratty, Broghill with a Parliamentarian force from Cork captured Blarney Castle. It must have been a bold coup as Muskerry was accused of having betrayed the castle.

Rejection of the First Ormond Peace

Muskerry and Ormond confirmed and signed the First Ormond Peace again in July 1646. The peace was thus concluded twice: on 28 March and in July 1646. Muskerry got the treatyratified

Ratification is a principal's approval of an act of its agent that lacked the authority to bind the principal legally. Ratification defines the international act in which a state indicates its consent to be bound to a treaty if the parties inte ...

by a vote in the Supreme Council despite the nuncio's opposition. Ormond had it proclaimed in Dublin on 30 July and the Supreme Council did so in Kilkenny on 3 August.

Rinuccini held a meeting of the clergy at Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

, which on 12 August 1646 condemned the treaty. Rinuccini then excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

Muskerry and others who supported it. On 18 September, Rinuccini overturned the Confederate government in a coup d'état with help of the Ulster Army, which Owen Roe O'Neill had marched to Leinster. On 26 September Rinuccini made himself president and appointed a new, the seventh, Supreme Council in which sat Glamorgan, Fermoy, and Owen Roe O'Neill. Rinuccini arrested Muskerry, Richard Bellings

Sir Richard Bellings (1613–1677) was a lawyer and political figure in 17th century Ireland and in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. He is best known for his participation in Confederate Ireland, a short-lived independent Irish state, in which ...

, and other Ormondist members of the previous Supreme Council. Most were detained in Kilkenny Castle, but Muskerry was put under house arrest. Muskerry had to cede the command of the Munster Army to Glamorgan. Being under arrest in Kilkenny Muskerry missed out on the attempted siege of Dublin by Owen Roe O'Neill and Preston in November 1646.

Having failed to take Dublin, Rinuccini released Muskerry and other political prisoners as demanded by Nicholas Plunkett

Sir Nicholas Plunkett (1602–1680) was an Anglo-Irish lawyer and politician. He was a younger son of Christopher Plunkett, 9th Baron Killeen and Jane (or Genet) Dillon, daughter of Sir Lucas Dillon: his brother Luke was created Earl of Fingall ...

, and called a general assembly, which met on 10 January 1647 in Kilkenny. It lasted until the beginning of April. The assembly elected a new Supreme Council, the eighth, with the Marquess of Antrim

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman wi ...

as president. It was dominated by the clerical faction but also included Muskerry and three other Ormondists.

Mutiny of the Munster Army

The Supreme Council had in 1647 confirmed Glamorgan, who had become the 2nd Marquess of Worcester in December 1646, as general of the Munster Army, but the Confederation lacked the funds to pay the army. Worcester was unpopular with the troops and the Munster gentry because he was English. Several regiments mutinied demanding that Muskerry should be appointed general. Three Dominican chaplains of the army insinuated that killing Muskerry would not be a sin. One of them was Patrick Hackett, a Gaelic poet. Gaelic was still the predominant language among the rank and file. Early in June 1647 the Supreme Council met atClonmel

Clonmel () is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Drogheda and Wexford. With the exception of the townland ...

near the Munster Army's camp. On 12 June Muskerry, together with Patrick Purcell, rode over from the council meeting to the army's camp where the troops acclaimed him as their leader and turned Worcester out of his command. The Supreme Council ignored Muskerry's de facto take-over, upheld Worcester as the de jure commander who then passed the command officially to Muskerry. Early in August Muskerry handed the command over to Theobald Viscount Taaffe of Corren. Neither Worcester, nor Muskerry, nor Taaffe stopped Inchiquin, who took Cappoquin and Dungarvan in May and sacked Cashel in September.

Decline of the Confederation

Meanwhile, on 6 June 1647, Ormond had accepted Colonel Michael Jones with 2,000 Parliamentarian troops into Dublin. On 28 July, Ormond handed Dublin over to the Parliamentarians and left for England. In August Preston tried to march on Dublin with the Leinster army, but Jones defeated him atDungan's Hill

Summerhill () is a heritage village in County Meath, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is located in the south of the county, between Trim, County Meath, Trim and Kilcock on the R158 road, R158 and west of Dunboyne on the R156 road, R156. It is ...

. Muskerry called in Owen Roe O'Neill to defend Leinster. In November, Taaffe lost the Battle of Knocknanuss against Inchiquin.

Towards the end of 1647, the Supreme Council sent Muskerry, Geoffrey Browne, and the Marquess of Antrim to negotiate with the exiled Queen Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

, at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

The Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a former royal palace in the commune of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the ''département'' of Yvelines, about 19 km west of Paris, France. Today, it houses the ''musée d'Archéologie nationale'' (Na ...

, France. They wanted to invite the Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rule ...

, the future Charles II, then aged 17, to Ireland, and negotiate another peace to replace the one concluded with Ormond. In February 1648 Ormond left England and joined the Queen. Antrim departed before Muskerry and Browne and arrived early in March. Muskerry and Browne departed in February and had reached Saint-Germain by 23 March. On 24 March 1648, the Queen received the three envoys in an audience. However, 1648 was the year of the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641–1653 Irish Confeder ...

and plans were made for the Prince of Wales to go to Scotland to support the Engagers

The Engagers were a faction of the Scottish Covenanters, who made "The Engagement" with King Charles I in December 1647 while he was imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle by the English Parliamentarians after his defeat in the First Civil War.

Bac ...

rather than to go to Ireland, but eventually, he stayed in France. With regard to a new peace, Antrim, representing the clerical faction, insisted that no peace should be accepted in Ireland without the pope's approval and that a Catholic lord lieutenant should be appointed, an office he hoped to obtain for himself.

On 3 April 1648, Inchiquin changed sides, leaving the Parliamentarians and declaring for the king. Muskerry convinced the Queen to appoint Ormond as lord lieutenant and Inchiquin as an ally. Muskerry returned to Ireland in June to prepare for Ormond's arrival. Ormond landed at Cork in September. Muskerry was made Irish lord high admiral and president of the high Court of Admiralty. In November he signed letters of marque for the privateers

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

'' Mary of Antrim'' and the ''St John of Waterford

ST, St, or St. may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Stanza, in poetry

* Suicidal Tendencies, an American heavy metal/hardcore punk band

* Star Trek, a science-fiction media franchise

* Summa Theologica, a compendium of Catholic philosophy ...

''.

In January 1649, the Second Ormond Peace was signed. The Irish Catholic Confederation was dissolved, and replaced with a provisional royalist government. Power was handed to 12 Commissioners of Trust. Muskerry was one of them.

Cromwellian conquest

On 15 August 1649,Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

landed in Dublin. He wanted to avenge the uprising of 1641, confiscate enough Irish Catholic-owned land to pay off the English Parliament's debts, and eliminate a dangerous outpost of royalism.

Boetius MacEgan

Boetius MacEgan ( ga, Baothnalach Mac Aodhagáin; died May 1650) was a 17th-century Irish Roman Catholic Bishop of Ross.

He was born in the barony of Duhallow in north-west County Cork and educated in France and Spain. He returned to his nativ ...

, Catholic Bishop of Ross, tried to relieve the Siege of Clonmel

The Siege of Clonmel, from 27 April to 18 May 1650, took place during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, when Clonmel in County Tipperary was besieged by 8,000 men from the New Model Army under Oliver Cromwell. The garrison of 1,500 c ...

. Led by Colonel David Roche and the bishop, this force passed by Macroom and camped in the castle's park. Macroom's garrison burned the castle and joined Roche's force, Cromwell sent Broghill to intercept the Irish, which were routed in the Battle of Macroom

The Battle of Macroom was a skirmish fought on 10 May 1650, near Macroom, County Cork, in southern Ireland, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. An English Parliamentarian force under Roger Boyle, (Lord Broghill), defeated an Iris ...

on 10 April. Clonmel surrendered to Cromwell in May. Cromwell had to hurry away to counter a threat from Scotland and passed the Irish command to Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton ((baptised) 3 November 1611 – 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 16 ...

on 19 May.

In April 1651 Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde

Ulick MacRichard Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde, 5th Earl of Clanricarde, 2nd Earl of St Albans (; ; ; ; 1604, in London – July 1657, in Kent), was an Anglo-Irish nobleman who was involved in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Catholic Ro ...

, appointed Muskerry supreme commander in Munster. Muskerry tried to relieve the Siege of Limerick, but Broghill intercepted and defeated him on 26 July 1651 at the Battle of Knocknaclashy

The battle of Knocknaclashy (also known as Knockbrack), took place in County Cork in southern Ireland in 1651. In it, an Irish Confederate force led by Viscount Muskerry was defeated by an English Parliamentarian force under Lord Broghil ...

(also called Knockbrack), near Dromagh Castle, west of Kanturk

Kanturk () is a town in the north west of County Cork, Ireland. It is situated at the confluence of the Allua (Allow) and Dallow (Dalua) rivers, which stream further on as tributaries to the River Blackwater. It is about from Cork, Blarney an ...

, the war's last pitched battle. Limerick surrendered in October.

Muskerry fell back into the mountains of Kerry

Kerry or Kerri may refer to:

* Kerry (name), a given name and surname of Gaelic origin (including a list of people with the name)

Places

* Kerry, Queensland, Australia

* County Kerry, Ireland

** Kerry Airport, an international airport in County ...

and based himself at Ross Castle

Ross Castle ( ga, Caisleán an Rois) is a 15th-century tower house and keep on the edge of Lough Leane, in Killarney National Park, County Kerry, Ireland. It is the ancestral home of the Chiefs of the Clan O'Donoghue, later associated w ...

near Killarney, owned by Sir Valentine Browne

Sir Valentine Browne (died 1589), of Croft, Lincolnshire, was auditor, treasurer and victualler of Berwick-upon-Tweed. He acquired large estates in Ireland during the Plantation of Munster, in particular the seignory of Molahiffe. He lived at ...

, his nephew by his sister Mary. Browne, born in 1638, was a minor and had become Muskerry's ward after his father's untimely death. In 1652 the government put a bounty of £500

(about £ in ) on Muskerry's head. Muskerry hoped that the Duke of Lorraine

The rulers of Lorraine have held different posts under different governments over different regions, since its creation as the kingdom of Lotharingia by the Treaty of Prüm, in 855. The first rulers of the newly established region were kings o ...

would intervene to save the Irish royalists.

Edmund Ludlow

Edmund Ludlow (c. 1617–1692) was an English parliamentarian, best known for his involvement in the execution of Charles I, and for his ''Memoirs'', which were published posthumously in a rewritten form and which have become a major source ...

besieged Muskerry in Ross Castle, on the shore of Lough Leane

Lough Leane (; ) is the largest of the three lakes of Killarney, in County Kerry. The River Laune flows from the lake into the Dingle Bay to the northwest.

Etymology and history

The lake's name means "lake of learning" probably in reference to ...

. The defenders were supplied by boat over the lake. Ludlow brought boats of his own whereupon Muskerry surrendered on 27 June 1652 after a siege of three weeks. The terms took a possible prosecution into account. Muskerry gave two hostages to guarantee his compliance with the terms: one of his sons and Daniel O'Brien. Muskerry disbanded his 5,000-strong army. He was excluded from pardon of life and estate in the Commonwealth's Act of Settlement

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, b ...

on 12 August and therefore lost his estates. His surrender was one of the last, but Clanricarde, 28 June, and Philip O'Reilly, 27 April 1653, surrendered later.

Exile and prosecution

Muskerry was allowed to embark for Spain where he was rejected as Ormondist. He then sought employment with theVenetian Republic

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

for himself and the Irish soldiers that he brought with him, but the project fell through. He returned to Ireland late in 1653 landing at Cork to recruit soldiers for service on the continent but was arrested for war crimes and detained until the opening of his trial on 1 December in Dublin. He was accused of having been an accessory to murders of English settlers on three occasions.

The first case was the murder of William Deane and others at Kilfinny, County Limerick, by soldiers of the Munster army on 29 July 1642. The victims died when Lady Dowdall surrendered Kilfinny Castle to Patrick Purcell, who commanded the besiegers. It had been agreed that the English would be allowed to leave escorted by a detachment sent by Inchiquin. The second case was the murder of Mrs Hussey and others near Blarney Castle, County Cork, by Irish soldiers on 1 August 1642. The victims were refugees that Muskerry had sheltered at Macroom and was sending to Cork in a guarded convoy so that they could leave the country. The third case was the murder of Roger Skinner and others at Inniskerry, County Cork, in August 1642. Muskerry was acquitted of these three charges.

In February 1654 he was tried for having participated in royalist conspiracies. Lady Ormond, who had been allowed to return to Ireland from her French exile, secretly visited Gerard Lowther, president of the High Court of Justice at the time, who gave her legal advice for Muskerry. This helped him convince the court of his innocence and he was acquitted.

In May 1654 he had to defend himself against another murder charge concerning the killing of an unnamed man and woman. He was acquitted.

Muskerry was again allowed to embark for Spain but went to France. Henrietta Maria, now the Queen Mother, still lived there, but in July 1654 Charles II and his exile court were about to leave France and start their wanderings in the Netherlands and Germany. Lady Muskerry lived in Paris. Muskerry's daughter Helen found shelter at the abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs

Port-Royal-des-Champs was an abbey of Cistercian nuns in Magny-les-Hameaux, in the Vallée de Chevreuse southwest of Paris that launched a number of culturally important institutions.

History

The abbey was established in 1204, but became fa ...

near Versailles. The abbess, La Mère Angélique, tried to help Muskerry and his Irish soldiers in their need. In November 1654 she wrote to Queen Marie Louise Gonzaga

Marie Louise Gonzaga ( pl, Ludwika Maria; 18 August 1611 – 10 May 1667) was Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania by marriage to two kings of Poland and grand dukes of Lithuania, brothers Władysław IV and John II Casimir. Toget ...

of Poland proposing to employ Muskerry and his followers – 5,000 men – in Polish service. In 1655 Muskerry and Bellings led them to the Polish King, who fought the Swedes in the Second Northern War

The Second Northern War (1655–60), (also First or Little Northern War) was fought between Sweden and its adversaries the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1655–60), the Tsardom of Russia ( 1656–58), Brandenburg-Prussia (1657–60), th ...

. Muskerry and Bellings returned with £20,000 for Charles II. In 1657 the King sent Muskerry to Madrid to ask the Spanish to let the Irish exiles now in Spain invade Ireland. They stayed seven months but achieved nothing. Muskerry's eldest son fought the French and Cromwell's English at the Battle of the Dunes in June 1658 The King, in exile at Brussels, rewarded Muskerry in November 1658 with the title of Earl of Clancarty. His title of Viscount Muskerry, now subsidiary, passed to his eldest son Charles, his heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

, as courtesy title

A courtesy title is a title that does not have legal significance but rather is used through custom or courtesy, particularly, in the context of nobility, the titles used by children of members of the nobility (cf. substantive title).

In some c ...

.

Restoration and death

At the Restoration of the Stuarts, Clancarty, as he now was, returned to Ireland. He used Ormond's influence to recover his estates, which Charles II confirmed to him in his "Gracious Declaration" of 30 November 1660. The Cromwellian occupiers had to leave at once. Now-Admiral William Penn, to whom Macroom had been granted in 1654, was compensated with land at

At the Restoration of the Stuarts, Clancarty, as he now was, returned to Ireland. He used Ormond's influence to recover his estates, which Charles II confirmed to him in his "Gracious Declaration" of 30 November 1660. The Cromwellian occupiers had to leave at once. Now-Admiral William Penn, to whom Macroom had been granted in 1654, was compensated with land at Shanagarry

Shanagarry () is a village in east County Cork in Ireland. The village is located near Ireland's south coast, approximately east of Cork, on the R632 regional road.

Shanagarry is known for the Ballymaloe Cookery School, in the home and garden ...

(east of Cork). Broghill had to return Blarney and Kilcrea

Kilcrea Friary () is a ruined medieval abbey located near Ovens, County Cork, Ireland. Both the friary and Kilcrea Castle, located in ruin to the west, were built by Observant Franciscans in the mid 15th century under the invitation of Cormac ...

. The Clancartys repaired and enlarged Macroom Castle. Clancarty also recovered his townhouse, which now became Clancarty House. Clancarty found wealthy Irish spouses for his eldest son and his two daughters. This son married Margaret Bourke in 1660 or 1661. She was a rich heiress, the only child of Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde. Clancarty's elder daughter Helen married first after 1660 Sir John FitzGerald of Dromana

Sir John FitzGerald of Dromana ( – 1662 or 1664) was the last of the FitzGeralds of Dromana. He sat as MP for Dungarvan in the Irish Parliament of 1661–1666.

Birth and origins

John was born about 1635 probab ...

, a Protestant, as his second wife. The marriage was childless. After his death in 1664 Helen married secondly William Burke, 7th Earl of Clanricarde

William Burke, 7th Earl of Clanricarde, PC (Ire) (; ; died 1687), was an Irish peer who fought in his youth together with his brother Richard, 6th Earl of Clanricarde under their cousin, Ulick Burke, 1st Marquess of Clanricarde against the P ...

. Clancarty's younger daughter Margaret married Luke Plunket, 3rd Earl of Fingall, before 1666.

In the winter of 1661/2, Clancarty signed the Catholic Remonstrance drawn up by Bellings and promoted by Peter Walsh. in an attempt to improve the Catholics' condition in Ireland by demonstrating their loyalty to the King. However, the remonstrance proved inefficient, mainly because too few of the clergy signed.

In August 1660, Charles II made George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle

George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle JP KG PC (6 December 1608 – 3 January 1670) was an English soldier, who fought on both sides during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A prominent military figure under the Commonwealth, his support was cru ...

, lord lieutenant of Ireland. As Albemarle never went to Ireland, the King appointed three lords justices to govern in his stead. When the King summoned the Parliament of 1661–1666, it was opened by the lords justices on 8 May 1661. Clancarty joined the House of Lords on 20 May. On 11 June Clancarty became the proxy of Lord Inchiquin, therefore voting in his stead. The passing of the Act of Settlement

The Act of Settlement is an Act of the Parliament of England that settled the succession to the English and Irish crowns to only Protestants, which passed in 1701. More specifically, anyone who became a Roman Catholic, or who married one, b ...

was one of the main purposes of the parliament. Clancarty was absent on 30 May 1662 when the Lords finally passed it. Clancarty sat on the committee that organised the gift of £30,000 (about £ in ) made to the Duke of Ormond. However, Clancarty's eldest son, Charles MacCarty, replaced him in that function on 19 August. On 11 December, the Lords passed the Irish version of the Tenures Abolition Act 1660

The Tenures Abolition Act 1660 (12 Car 2 c 24), sometimes known as the Statute of Tenures, was an Act of the Parliament of England which changed the nature of several types of feudal land tenure in England. The long title of the Act was ''An act ...

. Clancarty attended parliament regularly until April 1663 when he moved to London. He visited his Irish estates in 1664 for a last time and returned to England.

On 3 June 1665, Charles, Viscount Muskerry, Clancarty's eldest son and heir apparent, was killed during the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes, whe ...

in the Battle of Lowestoft

The Battle of Lowestoft took place on during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. A fleet of more than a hundred ships of the United Provinces commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Jacob van Wassenaer, Lord Obdam attacked an English fleet of equal size comm ...

, a naval engagement with the Dutch and buried in Westminster Abbey as his grandfather, the 1st Viscount, had been.77/> Charles left an infant son, called Charles James, who became the new heir apparent. Only one and a half months later, on 4 or 5 August 1665, Clancarty died at Ormond's house at Moor Park, Hertfordshire. Ormond, despite being a Protestant, called in a Catholic priest for the last rites of his friend. The Catholic political pamphlet ''The Unkinde Deserter of Loyall Men and True Frinds'' claims that in his last hour Clancarty expressed regret at having trusted Ormond. Charles's infant son Charles James succeeded his grandfather as the 2nd Earl of Clancarty but died a year later. The succession then reverted to the 1st Earl's second son, Callaghan, who succeeded as the 3rd Earl of Clancarty.

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

Sources

Subject matter monographs: * Click here. McGrath 1997a in ''A Biographical Dictionary of the Membership of the Irish House of Commons 1640 to 1641'' * Click here. Ohlmeyer 2004 inOxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

* Click here. Ó Siochrú in Dictionary of Irish Biography

The ''Dictionary of Irish Biography'' (DIB) is a biographical dictionary of notable Irish people and people not born in the country who had notable careers in Ireland, including both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.Click here. Seccombe 1893 in

Portrait

at the Hunt Museum, Limerick

Biography of Donough MacCarthy, Viscount Muskerry