Division of labour on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, and either form combinations or trade to take advantage of the capabilities of others in addition to their own. Specialised capabilities may include equipment or

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, and either form combinations or trade to take advantage of the capabilities of others in addition to their own. Specialised capabilities may include equipment or  Historically, an increasing division of labour is associated with the growth of total

Historically, an increasing division of labour is associated with the growth of total

Sir William Petty was the first modern writer to take note of the division of labour, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically, the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. But the Dutch had it organised with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships. People with a particular task to do must have discovered new methods that were only later observed and justified by writers on political economy.

Petty also applied the principle to his survey of

Sir William Petty was the first modern writer to take note of the division of labour, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically, the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. But the Dutch had it organised with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships. People with a particular task to do must have discovered new methods that were only later observed and justified by writers on political economy.

Petty also applied the principle to his survey of

Bernard de Mandeville discussed the matter in the second volume of '' The Fable of the Bees'' (1714). This elaborates many matters raised by the original poem about a 'Grumbling Hive'. He says:

Bernard de Mandeville discussed the matter in the second volume of '' The Fable of the Bees'' (1714). This elaborates many matters raised by the original poem about a 'Grumbling Hive'. He says:

In his introduction to ''The Art of the Pin-Maker'' (''Art de l'Épinglier'', 1761), du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1761. " Introduction." In ''Art de l'Épinglier'', by R. Réaumur, and A. de Ferchault. Paris: Saillant et Nyon. Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau writes about the "division of this work":

By "division of this work," du Monceau is referring to the subdivisions of

the text describing the various trades involved in the pin making activity; this can also be described as a division of labour.

In his introduction to ''The Art of the Pin-Maker'' (''Art de l'Épinglier'', 1761), du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1761. " Introduction." In ''Art de l'Épinglier'', by R. Réaumur, and A. de Ferchault. Paris: Saillant et Nyon. Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau writes about the "division of this work":

By "division of this work," du Monceau is referring to the subdivisions of

the text describing the various trades involved in the pin making activity; this can also be described as a division of labour.

In the first sentence of ''

In the first sentence of ''

In the '' Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (1785), Immanuel Kant notes the value of the division of labour:

In the '' Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (1785), Immanuel Kant notes the value of the division of labour:

As social solidarity cannot be directly quantified, Durkheim indirectly studies solidarity by "classify ngthe different types of law to find...the different types of social solidarity which correspond to it." Durkheim categorises: Anderson, Margaret L. and Howard F. Taylor. 2008. ''Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Print.

* criminal laws and their respective punishments as promoting mechanical solidarity, a sense of unity resulting from individuals engaging in similar work who hold shared backgrounds, traditions, and values; and

* civil laws as promoting organic solidarity, a society in which individuals engage in different kinds of work that benefit society and other individuals.

Durkheim believes that organic solidarity prevails in more advanced societies, while mechanical solidarity typifies less developed societies. He explains that in societies with more mechanical solidarity, the diversity and division of labour is much less, so individuals have a similar worldview. Similarly, Durkheim opines that in societies with more organic solidarity, the diversity of occupations is greater, and individuals depend on each other more, resulting in greater benefits to society as a whole. Durkheim's work enabled

As social solidarity cannot be directly quantified, Durkheim indirectly studies solidarity by "classify ngthe different types of law to find...the different types of social solidarity which correspond to it." Durkheim categorises: Anderson, Margaret L. and Howard F. Taylor. 2008. ''Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Print.

* criminal laws and their respective punishments as promoting mechanical solidarity, a sense of unity resulting from individuals engaging in similar work who hold shared backgrounds, traditions, and values; and

* civil laws as promoting organic solidarity, a society in which individuals engage in different kinds of work that benefit society and other individuals.

Durkheim believes that organic solidarity prevails in more advanced societies, while mechanical solidarity typifies less developed societies. He explains that in societies with more mechanical solidarity, the diversity and division of labour is much less, so individuals have a similar worldview. Similarly, Durkheim opines that in societies with more organic solidarity, the diversity of occupations is greater, and individuals depend on each other more, resulting in greater benefits to society as a whole. Durkheim's work enabled

Marx's theories, including his negative claims regarding the division of labour, have been criticised by the Austrian economists, notably Ludwig von Mises. The primary argument is that the economic gains accruing from the division of labour far outweigh the costs, thus developing on the thesis that division of labor leads to cost efficiencies. It is argued that it is fully possible to achieve balanced human development within

Marx's theories, including his negative claims regarding the division of labour, have been criticised by the Austrian economists, notably Ludwig von Mises. The primary argument is that the economic gains accruing from the division of labour far outweigh the costs, thus developing on the thesis that division of labor leads to cost efficiencies. It is argued that it is fully possible to achieve balanced human development within

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, and either form combinations or trade to take advantage of the capabilities of others in addition to their own. Specialised capabilities may include equipment or

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (specialisation). Individuals, organizations, and nations are endowed with, or acquire specialised capabilities, and either form combinations or trade to take advantage of the capabilities of others in addition to their own. Specialised capabilities may include equipment or natural resource

Natural resources are resources that are drawn from nature and used with few modifications. This includes the sources of valued characteristics such as commercial and industrial use, aesthetic value, scientific interest and cultural value. ...

s as well as skills, and training and combinations of such assets acting together are often important. For example, an individual may specialise by acquiring tools and the skills to use them effectively just as an organization may specialise by acquiring specialised equipment and hiring or training skilled operators. The division of labour is the motive for trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

and the source of economic interdependence.

output

Output may refer to:

* The information produced by a computer, see Input/output

* An output state of a system, see state (computer science)

* Output (economics), the amount of goods and services produced

** Gross output in economics, the value ...

and trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

, the rise of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

, and the increasing complexity of industrialised

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econom ...

processes. The concept and implementation of division of labour has been observed in ancient Sumerian (Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

n) culture, where assignment of jobs in some cities coincided with an increase in trade and economic interdependence. Division of labour generally also increases both producer and individual worker productivity.

After the Neolithic Revolution, pastoralism and agriculture led to more reliable and abundant food supplies, which increased the population and led to specialisation of labour, including new classes of artisans, warriors, and the development of elites. This specialisation was furthered by the process of industrialisation, and Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

-era factories. Accordingly, many classical economists as well as some mechanical engineers, such as Charles Babbage, were proponents of division of labour. Also, having workers perform single or limited tasks eliminated the long training period required to train craftsmen, who were replaced with less-paid but more productive unskilled workers.

Ancient theories

Plato

InPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

's '' Republic'', the origin of the state lies in the natural inequality of humanity, which is embodied in the division of labour:

Silvermintz (2010) notes that "Historians of economic thought credit Plato, primarily on account of arguments advanced in his Republic, as an early proponent of the division of labour." Notwithstanding this, Silvermintz argues that "While Plato recognises both the economic and political benefits of the division of labour, he ultimately critiques this form of economic arrangement insofar as it hinders the individual from ordering his own soul by cultivating acquisitive motives over prudence and reason."

Xenophon

Xenophon, in the 4th century BC, makes a passing reference to division of labour in his '' Cyropaedia'' (a.k.a. ''Education of Cyrus'').Augustine of Hippo

A simile used by Augustine of Hippo shows that the division of labour was practised and understood in late Imperial Rome. In a brief passage of his '' The City of God'', Augustine seems to be aware of the role of different social layers in the production of goods, like household ( ''familiae''), corporations (''collegia'') and the state.Ibn Khaldun

The 14th-century scholar Ibn Khaldun emphasised the importance of the division of labour in the production process. In his '' Muqaddimah'', he states:Modern theories

William Petty

Sir William Petty was the first modern writer to take note of the division of labour, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically, the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. But the Dutch had it organised with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships. People with a particular task to do must have discovered new methods that were only later observed and justified by writers on political economy.

Petty also applied the principle to his survey of

Sir William Petty was the first modern writer to take note of the division of labour, showing its existence and usefulness in Dutch shipyards. Classically, the workers in a shipyard would build ships as units, finishing one before starting another. But the Dutch had it organised with several teams each doing the same tasks for successive ships. People with a particular task to do must have discovered new methods that were only later observed and justified by writers on political economy.

Petty also applied the principle to his survey of Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. His breakthrough was to divide up the work so that large parts of it could be done by people with no extensive training.

Bernard de Mandeville

Bernard de Mandeville discussed the matter in the second volume of '' The Fable of the Bees'' (1714). This elaborates many matters raised by the original poem about a 'Grumbling Hive'. He says:

Bernard de Mandeville discussed the matter in the second volume of '' The Fable of the Bees'' (1714). This elaborates many matters raised by the original poem about a 'Grumbling Hive'. He says:

David Hume

- David Hume, A Treatise on Human NatureHenri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau

In his introduction to ''The Art of the Pin-Maker'' (''Art de l'Épinglier'', 1761), du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1761. " Introduction." In ''Art de l'Épinglier'', by R. Réaumur, and A. de Ferchault. Paris: Saillant et Nyon. Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau writes about the "division of this work":

By "division of this work," du Monceau is referring to the subdivisions of

the text describing the various trades involved in the pin making activity; this can also be described as a division of labour.

In his introduction to ''The Art of the Pin-Maker'' (''Art de l'Épinglier'', 1761), du Monceau, Henri-Louis Duhamel. 1761. " Introduction." In ''Art de l'Épinglier'', by R. Réaumur, and A. de Ferchault. Paris: Saillant et Nyon. Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau writes about the "division of this work":

By "division of this work," du Monceau is referring to the subdivisions of

the text describing the various trades involved in the pin making activity; this can also be described as a division of labour.

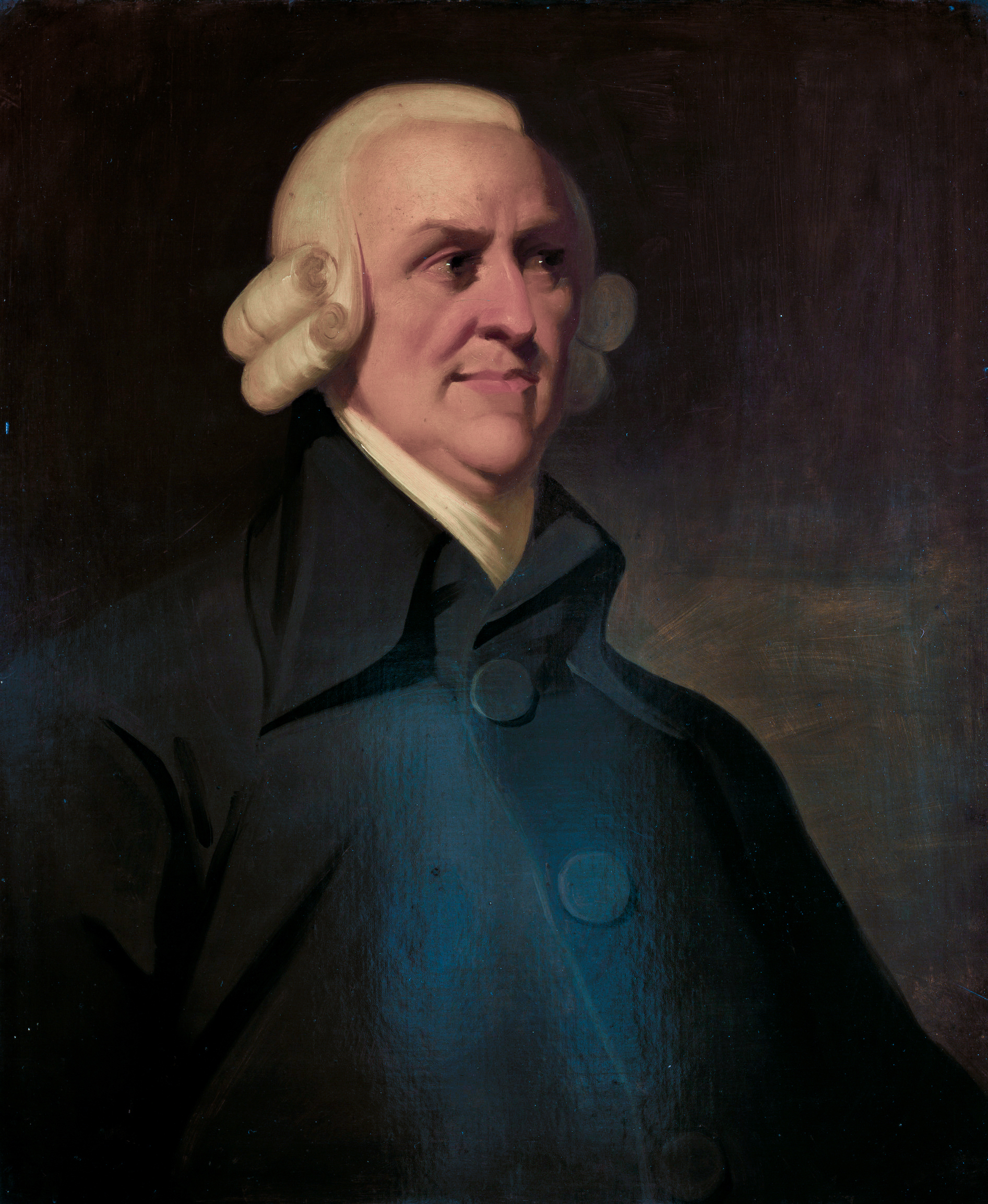

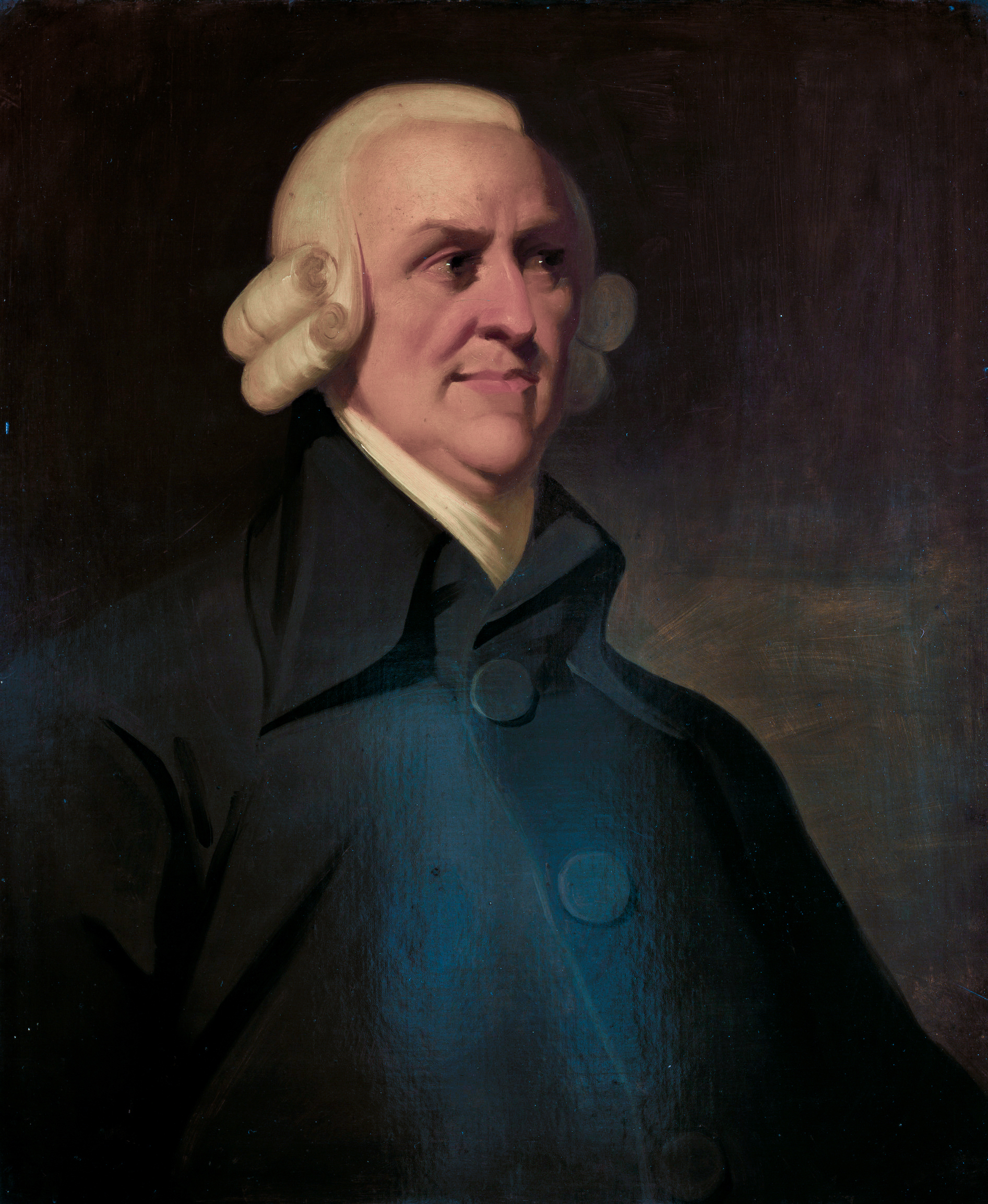

Adam Smith

In the first sentence of ''

In the first sentence of ''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the ''Masterpiece, magnum opus'' of the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosopher Ada ...

'' (1776), Adam Smith foresaw the essence of industrialism by determining that division of labour represents a substantial increase in productivity. Like du Monceau, his example was the making of pins.

Unlike Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, Smith famously argued that the difference between a street porter and a philosopher was as much a consequence of the division of labour as its cause. Therefore, while for Plato the level of specialisation determined by the division of labour was externally determined, for Smith it was the dynamic engine of economic progress. However, in a further chapter of the same book, Smith criticised the division of labour saying it can lead to "the almost entire corruption and degeneracy of the great body of the people.…unless the government takes some pains to prevent it." The contradiction has led to some debate over Smith's opinion of the division of labour. Alexis de Tocqueville agreed with Smith: "Nothing tends to materialize man, and to deprive his work of the faintest trace of mind, more than extreme division of labor." Adam Ferguson shared similar views to Smith, though was generally more negative.

The specialisation and concentration of the workers on their single subtasks often leads to greater skill and greater productivity on their particular subtasks than would be achieved by the same number of workers each carrying out the original broad task, in part due to increased quality of production, but more importantly because of increased efficiency of production, leading to a higher nominal output of units produced per time unit. Smith uses the example of a production capability of an individual pin maker compared to a manufacturing business that employed 10 men:One man draws out the wire; another straights it; a third cuts it; a fourth points it; a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business; to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind, where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty-eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day.Smith saw the importance of matching skills with equipment—usually in the context of an organisation. For example, pin makers were organised with one making the head, another the body, each using different equipment. Similarly, he emphasised a large number of skills, used in cooperation and with suitable equipment, were required to build a ship. In the modern economic discussion, the term '' human capital'' would be used. Smith's insight suggests that the huge increases in productivity obtainable from

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, scie ...

or technological progress are possible because human and physical capital are matched, usually in an organisation. See also a short discussion of Adam Smith's theory in the context of business processes. Babbage wrote a seminal work "On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures" analysing perhaps for the first time the division of labour in factories.

Immanuel Kant

In the '' Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (1785), Immanuel Kant notes the value of the division of labour:

In the '' Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals'' (1785), Immanuel Kant notes the value of the division of labour:All crafts, trades and arts have profited from the division of labour; for when each worker sticks to one particular kind of work that needs to be handled differently from all the others, he can do it better and more easily than when one person does everything. Where work is not thus differentiated and divided, where everyone is a jack-of-all-trades, the crafts remain at an utterly primitive level.

Karl Marx

Marx argued that increasing the specialisation may also lead to workers with poorer overall skills and a lack of enthusiasm for their work. He described the process asalienation

Alienation may refer to:

* Alienation (property law), the legal transfer of title of ownership to another party

* ''Alienation'' (video game), a 2016 PlayStation 4 video game

* "Alienation" (speech), an inaugural address by Jimmy Reid as Rector ...

: workers become more and more specialised and work becomes repetitive, eventually leading to complete alienation from the process of production. The worker then becomes "depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine."

Additionally, Marx argued that the division of labour creates less-skilled workers. As the work becomes more specialised, less training is needed for each specific job, and the workforce, overall, is less skilled than if one worker did one job entirely.

Among Marx's theoretical contributions is his sharp distinction between the economic and the social division of labour. That is, some forms of labour co-operation are purely due to "technical necessity", but others are a result of a "social control" function related to a class and status hierarchy. If these two divisions are conflated, it might appear as though the existing division of labour is technically inevitable and immutable, rather than (in good part) socially constructed and influenced by power relationships. He also argues that in a communist society, the division of labour is transcended, meaning that balanced human development occurs where people fully express their nature in the variety of creative work that they do.

Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Henry David Thoreau criticised the division of labour in '' Walden'' (1854), on the basis that it removes people from a sense of connectedness with society and with the world at large, including nature. He claimed that the average man in a civilised society is less wealthy, in practice than one in "savage" society. The answer he gave was that self-sufficiency was enough to cover one's basic needs. Thoreau's friend and mentor,Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a cham ...

, criticised the division of labour in his "The American Scholar

"The American Scholar" was a speech given by Ralph Waldo Emerson on August 31, 1837, to the Phi Beta Kappa Society of Harvard College at the First Parish in Cambridge in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was invited to speak in recognition of his g ...

" speech: a widely informed, holistic citizenry is vital for the spiritual and physical health of the country.

Émile Durkheim

In his seminal work, '' The Division of Labor in Society'', Émile Durkheim observes that the division of labour appears in all societies and positively correlates with societal advancement because it increases as a society progresses. Durkheim arrived at the same conclusion regarding the positive effects of the division of labour as his theoretical predecessor, Adam Smith. In ''The Wealth of Nations'', Smith observes the division of labour results in "a proportionable increase of the productive powers of labour." While they shared this belief, Durkheim believed the division of labour applied to all "biological organisms generally," while Smith believed this law applied "only to human societies."Jones, Robert. 1986. ''Emile Durkheim: An Introduction to Four Major Works.'' Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Print. This difference may result from the influence ofCharles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's '' On the Origin of Species'' on Durkheim's writings. For example, Durkheim observed an apparent relationship between "the functional specialisation of the parts of an organism" and "the extent of that organism's evolutionary development," which he believed "extended the scope of the division of labour so as to make its origins contemporaneous with the origins of life itself…implying that its conditions must be found in the essential properties of all organised matter."

Since Durkheim's division of labour applied to all organisms, he considered it a "natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacted ...

" and worked to determine whether it should be embraced or resisted by first analysing its functions. Durkheim hypothesised that the division of labour fosters social solidarity, yielding "a wholly moral phenomenon" that ensures "mutual relationships" among individuals.Durkheim, Emile. 8931997. '' The Division of Labor in Society.'' New York: The Free Press. Print.

As social solidarity cannot be directly quantified, Durkheim indirectly studies solidarity by "classify ngthe different types of law to find...the different types of social solidarity which correspond to it." Durkheim categorises: Anderson, Margaret L. and Howard F. Taylor. 2008. ''Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Print.

* criminal laws and their respective punishments as promoting mechanical solidarity, a sense of unity resulting from individuals engaging in similar work who hold shared backgrounds, traditions, and values; and

* civil laws as promoting organic solidarity, a society in which individuals engage in different kinds of work that benefit society and other individuals.

Durkheim believes that organic solidarity prevails in more advanced societies, while mechanical solidarity typifies less developed societies. He explains that in societies with more mechanical solidarity, the diversity and division of labour is much less, so individuals have a similar worldview. Similarly, Durkheim opines that in societies with more organic solidarity, the diversity of occupations is greater, and individuals depend on each other more, resulting in greater benefits to society as a whole. Durkheim's work enabled

As social solidarity cannot be directly quantified, Durkheim indirectly studies solidarity by "classify ngthe different types of law to find...the different types of social solidarity which correspond to it." Durkheim categorises: Anderson, Margaret L. and Howard F. Taylor. 2008. ''Sociology: Understanding a Diverse Society.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. Print.

* criminal laws and their respective punishments as promoting mechanical solidarity, a sense of unity resulting from individuals engaging in similar work who hold shared backgrounds, traditions, and values; and

* civil laws as promoting organic solidarity, a society in which individuals engage in different kinds of work that benefit society and other individuals.

Durkheim believes that organic solidarity prevails in more advanced societies, while mechanical solidarity typifies less developed societies. He explains that in societies with more mechanical solidarity, the diversity and division of labour is much less, so individuals have a similar worldview. Similarly, Durkheim opines that in societies with more organic solidarity, the diversity of occupations is greater, and individuals depend on each other more, resulting in greater benefits to society as a whole. Durkheim's work enabled social science

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soc ...

to progress more efficiently "in…the understanding of human social behavior."

Ludwig von Mises

Marx's theories, including his negative claims regarding the division of labour, have been criticised by the Austrian economists, notably Ludwig von Mises. The primary argument is that the economic gains accruing from the division of labour far outweigh the costs, thus developing on the thesis that division of labor leads to cost efficiencies. It is argued that it is fully possible to achieve balanced human development within

Marx's theories, including his negative claims regarding the division of labour, have been criticised by the Austrian economists, notably Ludwig von Mises. The primary argument is that the economic gains accruing from the division of labour far outweigh the costs, thus developing on the thesis that division of labor leads to cost efficiencies. It is argued that it is fully possible to achieve balanced human development within capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

and alienation

Alienation may refer to:

* Alienation (property law), the legal transfer of title of ownership to another party

* ''Alienation'' (video game), a 2016 PlayStation 4 video game

* "Alienation" (speech), an inaugural address by Jimmy Reid as Rector ...

is downplayed as mere romantic fiction.

According to Mises, the idea has led to the concept of mechanization

Mechanization is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text a machine is defined as follows:

In some fields, mechanization includes the ...

in which a specific task is performed by a mechanical device, instead of an individual labourer. This method of production is significantly more effective in both yield and cost-effectiveness, and utilises the division of labour to the fullest extent possible. Mises saw the very idea of a task being performed by a specialised mechanical device as being the greatest achievement of division of labour.

Friedrich A. Hayek

In " The Use of Knowledge in Society", Friedrich A. Hayek states:

Globalisation and global division of labour

The issue reaches its broadest scope in the controversies about globalisation, which is often interpreted as a euphemism for the expansion ofinternational trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (see: World economy)

In most countries, such trade represents a significan ...

based on comparative advantage. This would mean that countries specialise in the work they can do at the lowest relative cost measured in terms of the opportunity cost of not using resources for other work, compared to the opportunity costs experienced by countries. Critics, however, allege that international specialisation cannot be explained sufficiently in terms of "the work nations do best", rather that this specialisation is guided more by commercial criteria, which favour some countries over others.

The OECD advised in June 2005 that:

Few studies have taken place regarding the global division of labour. Information can be drawn from ILO

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and ol ...

and national statistical offices. In one study, Deon Filmer estimated that 2.474 billion people participated in the global non-domestic labour force in the mid-1990s. Of these:

* around 15%, or 379 million people, worked in the industry;

* a third, or 800 million worked in services and

* over 40%, or 1,074 million, in agriculture.

The majority of workers in industry and services were wage and salary earners—58 percent of the industrial workforce and 65 percent of the services workforce. But a large portion was self-employed or involved in family labour. Filmer suggests the total of employees worldwide in the 1990s was about 880 million, compared with around a billion working on their own account on the land (mainly peasants), and some 480 million working on their own account in industry and services. The 2007 ILO

The International Labour Organization (ILO) is a United Nations agency whose mandate is to advance social and economic justice by setting international labour standards. Founded in October 1919 under the League of Nations, it is the first and ol ...

Global Employment Trends Report indicated that services have surpassed agriculture for the first time in human history:In 2006 the service sector’s share of global employment overtook agriculture for the first time, increasing from 39.5 to 40 percent. Agriculture decreased from 39.7 percent to 38.7 percent. The industry sector accounted for 21.3 percent of total employment.

Contemporary theories

In the modern world, those specialists most preoccupied in their work with theorising about the division of labour are those involved in management and organisation. In general, in capitalist economies, such things are not decided consciously. Different people try different things, and that which is most effective cost-wise (produces the most and best output with the least input) will generally be adopted. Often, techniques that work in one place or time do not work as well in another.Styles of division of labour

Two styles of management that are seen in modern organisations are control and commitment:McAlister-Kizzier, Donna. 2007. "Division of Labor." ''Encyclopedia of Business and Finance'' (2nd ed.). – viaEncyclopedia.com

Encyclopedia.com (also known as HighBeam Encyclopedia) is an online encyclopedia. It aggregates information from other published dictionaries, encyclopedias and reference works including pictures and videos.

History

The website was launched by ...

. 1 December 2014

# Control management, the style of the past, is based on the principles of job specialisation and the division of labour. This is the assembly-line style of job specialisation, where employees are given a very narrow set of tasks or one specific task.

# Commitment division of labour, the style of the future, is oriented on including the employee and building a level of internal commitment towards accomplishing tasks. Tasks include more responsibility and are coordinated based on expertise rather than a formal position.

Job specialisation is advantageous in developing employee expertise in a field and boosting organisational production. However, disadvantages of job specialisation included limited employee skill, dependence on entire department fluency, and employee discontent with repetitive tasks.

Labour hierarchy

It is widely accepted among economists and social theorists that the division of labour is, to a great extent, inevitable within capitalist societies, simply because no one can do all tasks at once. Labour hierarchy is a very common feature of the modern capitalist workplace structure, and the way these hierarchies are structured can be influenced by a variety of different factors, including: * Size: as organisations increase in size, there is a correlation in the rise of the division of labour. * Cost: cost limits small organisations from dividing their labour responsibilities. * Development of new technology: technological developments have led to a decrease in the amount of job specialisation in organisations as new technology makes it easier for fewer employees to accomplish a variety of tasks and still enhance production. New technology has also been helpful in the flow of information between departments helping to reduce the feeling of department isolation. It is often argued that the most equitable principle in allocating people within hierarchies is that of true (or proven) competency or ability. This concept of meritocracy could be read as an explanation or as a justification of why a division of labour is the way it is. This claim, however, is often disputed by various sources, particularly: * Marxists claim hierarchy is created to support the power structures in capitalist societies which maintain the capitalist class as the owner of the labour of workers, in order to exploit it. Anarchists often add to this analysis by defending that the presence of coercive hierarchy in any form is contrary to the values of liberty and equality. *Anti-imperialists

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is a term used in a variety of contexts, usually by nationalist movements who want to secede from a larger polity (usually in the form of an empire, but also in a multi-ethnic so ...

see the globalised labour hierarchy between