Diseases And Epidemics Of The 19th Century on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as

In London, in June 1866Johnson, S: The Ghost Map(), a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems.

In London, in June 1866Johnson, S: The Ghost Map(), a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems.

Cholera is an infection of the

Cholera is an infection of the

UCLA School of Public Health. A two-year outbreak began in The

The

This disease is transmitted by the bite of female mosquito; the higher prevalence of transmission by

This disease is transmitted by the bite of female mosquito; the higher prevalence of transmission by

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

, yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. In ...

, and scarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

. In addition, cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

emerged as an epidemic threat and spread worldwide in six pandemics in the nineteenth century. The third plague pandemic

The third plague pandemic was a major bubonic plague pandemic that began in Yunnan, China, in 1855. This episode of bubonic plague spread to all inhabited continents, and ultimately led to more than 12 million deaths in India and China (and perha ...

emerged in China in the mid-nineteenth century and spread worldwide in the 1890s.

Medical responses

Medicine in the 19th century

Epidemics of the 19th century were faced without the medical advances that made 20th-century epidemics much rarer and less lethal.Micro-organisms

A microorganism, or microbe,, ''mikros'', "small") and ''organism'' from the el, ὀργανισμός, ''organismós'', "organism"). It is usually written as a single word but is sometimes hyphenated (''micro-organism''), especially in olde ...

(viruses and bacteria) had been discovered in the 18th century, but it was not until the late 19th century that the experiments of Lazzaro Spallanzani and Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named afte ...

disproved spontaneous generation conclusively, allowing germ theory

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade ...

and Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

's discovery of micro-organisms as the cause of disease transmission

In medicine, public health, and biology, transmission is the passing of a pathogen causing communicable disease from an infected host individual or group to a particular individual or group, regardless of whether the other individual was previous ...

. Thus throughout the majority of the 19th century, there was only the most basic, common-sense understanding of the causes, amelioration, and treatment of epidemic disease.

The 19th century did, however, mark a transformation period in medicine. This included the first uses of chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, HChlorine, Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to ...

and nitrous dioxides as anesthesia, important discoveries in regards of pathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

and the perfection of the autopsy

An autopsy (post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of death or to evaluate any di ...

, and advances in our understanding of the human body. Medical institutions were also transitioning to new hospital styles to try to prevent the spread of disease and stop over crowding with the mixing of the poor and the sick which had been a common practice. With the increasing rise in urban population, disease and epidemic crisis became much more prevalent and was seen as a consequence of urban living. Problems arose as both governments and the medical professionals at the time tried to get a handle on the spread of disease. They had yet to figure out what actually causes disease. So as those in authority scrambled to make leaps and bounds in science and track down what may be the cause of these epidemics, entire communities would be lost to the grips of terrible ailments.

Exploring Potential Cures

During these many outbreaks, members of the medical professional rapidly began trying different cures to treat their patients. During thecholera epidemic of 1832

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

in London one doctor had found a cure. His name was Thomas Latta

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

and he figured out that by injecting saline solutions into the arms of those infected, they would survive the disease. But, because of the chaos of cures and treatments you could find being tried out on the streets, his cure was subsequently lost to the chaos of the times. In fact, a lot was lost this way. At this time, with the increasing circulation of mass media and no form of content review in medical journals, almost anyone with or without proper education could publish a potential cure for disease. Actual practicing medical professionals also had to compete with the ever expanding pharmacy companies that were all to ready to provide new elixirs and promising treatments for the epidemics of the time.

Emerging from the medical chaos were legitimate and life changing treatments. The late 19th century was the beginning of widespread use of vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

s. Baxby, Derrick (1999). "Edward Jenner's Inquiry; a bicentenary analysis". Vaccine 17 (4): 301–07 The cholera bacterium was isolated in 1854 by Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini, and a vaccine, the first to immunize humans against a bacterial disease, was developed by Spanish physician Jaume Ferran i Clua

''Jaime Ferrán y Clúa'' (Corbera d'Ebre, 1851 – Barcelona 1929) was a Spanish- French bacteriologist and sanitarian , contemporary of Robert Koch, and said by his fellows to have made some of the discoveries attributed to Koch. As early ...

in 1885, and by Russian–Jewish bacteriologist Waldemar Haffkine

Waldemar Mordechai Wolff Haffkine ( uk, Володимир Мордехай-Вольф Хавкін; russian: Мордехай-Вольф Хавкин; 15 March 1860 Odessa – 26 October 1930 Lausanne) was a Ukrainian-French bacteriologist kno ...

in July 1892.

Antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

drugs did not appear until the middle of the 20th century. Sulfonamide

In organic chemistry, the sulfonamide functional group (also spelled sulphonamide) is an organosulfur group with the structure . It consists of a sulfonyl group () connected to an amine group (). Relatively speaking this group is unreactive. ...

s did not appear until 1935, and penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' moulds, principally '' P. chrysogenum'' and '' P. rubens''. Most penicillins in clinical use are synthesised by P. chrysogenum using ...

, discovered in 1928, was not available as a treatment until 1950.

A big response and potential cure to these epidemics were better sanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

in the cities. Sanitation prior to this was very poor and sometimes attempts to get better sanitation often exacerbated the diseases, especially during the cholera epidemics because their understanding of diseases relied on the miasma (bad air) theory. During the first cholera epidemic, Edwin Chadwick

Sir Edwin Chadwick KCB (24 January 18006 July 1890) was an English social reformer who is noted for his leadership in reforming the Poor Laws in England and instituting major reforms in urban sanitation and public health. A disciple of Uti ...

made an inquiry into sanitation and used quantitative data to link poor living conditions and disease and low life expectancy. As a result, the Board of Health in London took measure to improve drainage and ventilation around the city. Unfortunately, the measures helped clean the city but it further contaminated the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

(the primary drinking water for the city) and the epidemic got worse.

Beliefs about the Causes

During the second cholera pandemic of 1816–1837, the scientific community varied in its beliefs about its causes. In France, doctors believed cholera was associated with the poverty of certain communities or poor environment. Russians believed the disease was contagious and quarantined their citizens. The United States believed that cholera was brought by recent immigrants, specifically the Irish. Lastly, some British thought the disease might arise from divine intervention. During the third pandemic, Tunisia, which had not been affected by the two previous pandemics, thought Europeans had brought the disease. They blamed theirsanitation

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage. Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems ...

practices. The prevalence of the disease in the South in areas of black populations convinced United States scientists that cholera was associated with African Americans. Current researchers note they lived near the waterways by which travelers and ships carried the disease and their populations were underserved with sanitation infrastructure and health care.

The Soho outbreak in London in 1854 ended after the physician John Snow

John Snow (15 March 1813 – 16 June 1858) was an English physician and a leader in the development of anaesthesia and medical hygiene. He is considered one of the founders of modern epidemiology, in part because of his work in tracing the so ...

identified a neighborhood Broad Street pump

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develo ...

as contaminated and convinced officials to remove its handle. Snow believed that germ-contaminated water was the source of cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

, rather than particles in the air (referred to as "miasmata"). His study proved contaminated water was the main agent spreading cholera, although he did not identify the contaminant. Though Filippo Pacini had isolated ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe and comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in brackish or saltwater where they attach themselves easily to the chitin-containing shells of crabs, shrimps, and oth ...

'' as the causative agent for cholera that year, it would be many years before miasma theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmatic theory) is an obsolete medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or the Black Death—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad ...

would fall out of favor.

In London, in June 1866Johnson, S: The Ghost Map(), a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems.

In London, in June 1866Johnson, S: The Ghost Map(), a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as the city was completing construction of its major sewage and water treatment systems. William Farr

William Farr CB (30 November 1807 – 14 April 1883) was a British epidemiologist, regarded as one of the founders of medical statistics.

Early life

William Farr was born in Kenley, Shropshire, to poor parents. He was effectively adopted by ...

, using the work of John Snow, ''et al.'', as to contaminated drinking water being the likely source of the disease, relatively quickly identified the East London Water Company as the source of the contaminated water. Quick action prevented further deaths.

During the fifth cholera pandemic

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash that ...

, Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( , ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera (though the Vibrio ...

isolated ''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe and comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in brackish or saltwater where they attach themselves easily to the chitin-containing shells of crabs, shrimps, and oth ...

'' and proposed postulates to explain how bacteria caused disease. His work helped to establish the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can lead to disease. These small organisms, too small to be seen without magnification, invade h ...

. Prior to this time, many physicians believed that microorganisms were spontaneously generated, and disease was caused by direct exposure to filth and decay. Koch helped establish that the disease was more specifically contagious

Contagious may refer to:

* Contagious disease

Literature

* Contagious (magazine), a marketing publication

* ''Contagious'' (novel), a science fiction thriller novel by Scott Sigler

Music

Albums

*''Contagious'' (Peggy Scott-Adams album), 1997

* ...

and was transmittable through the contaminated water supply. The fifth was the last serious European cholera outbreak, as cities improved their sanitation and water systems.

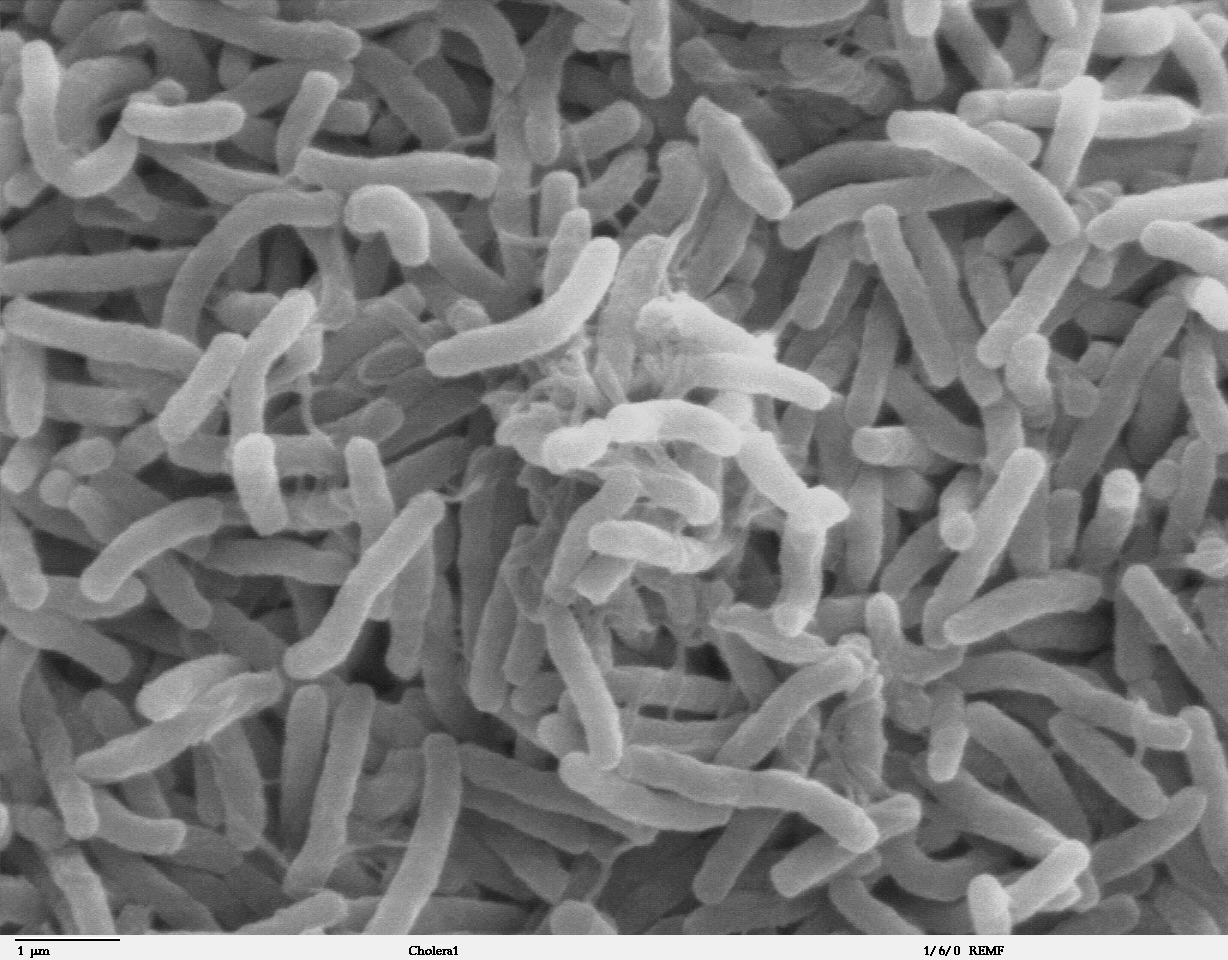

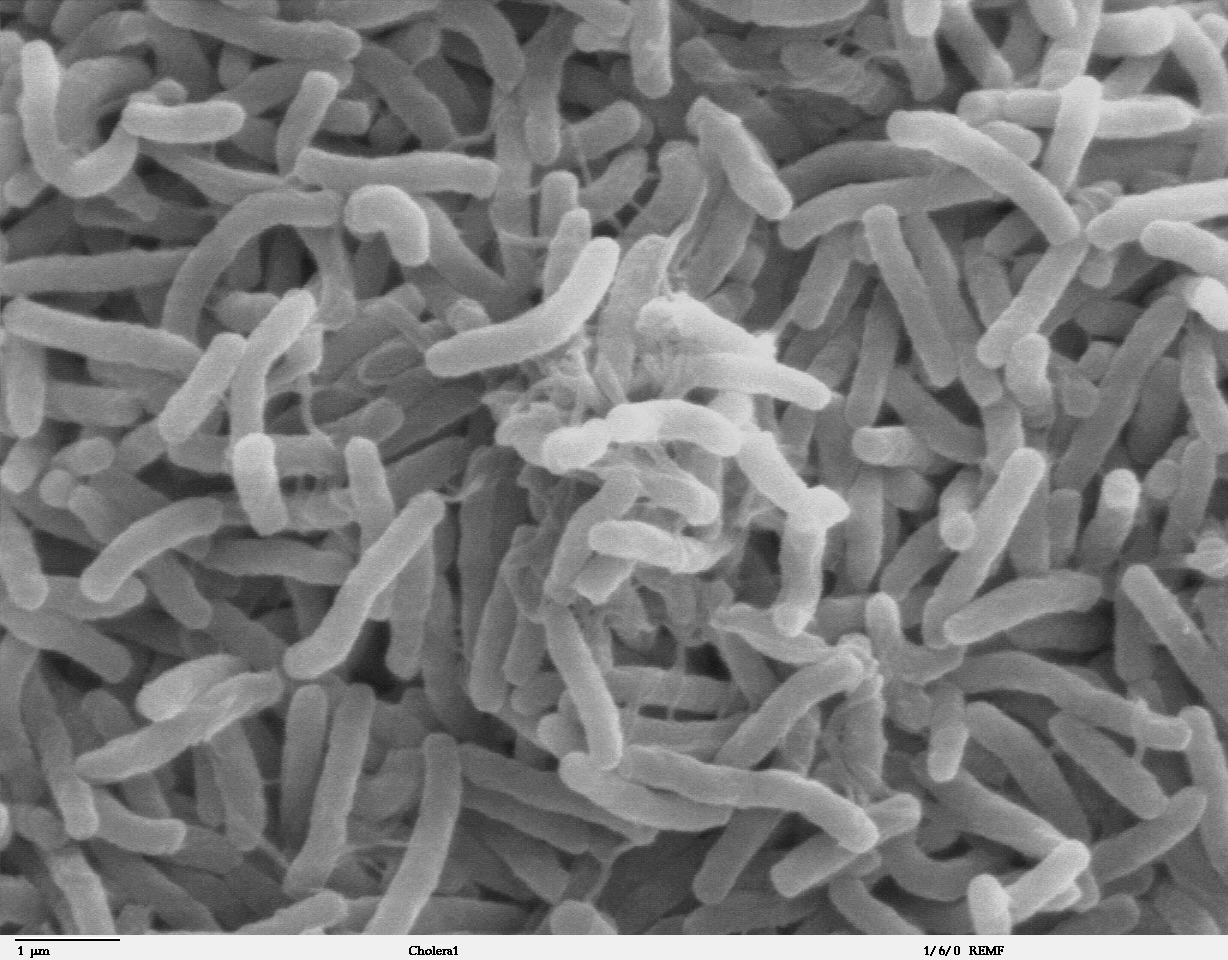

Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine

The small intestine or small bowel is an organ in the gastrointestinal tract where most of the absorption of nutrients from food takes place. It lies between the stomach and large intestine, and receives bile and pancreatic juice through the p ...

caused by the bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

''Vibrio cholerae

''Vibrio cholerae'' is a species of Gram-negative, facultative anaerobe and comma-shaped bacteria. The bacteria naturally live in brackish or saltwater where they attach themselves easily to the chitin-containing shells of crabs, shrimps, and oth ...

''. Cholera is transmitted primarily by drinking water or eating food that has been contaminated by the cholera bacterium. The bacteria multiply in the small intestine; the feces

Feces ( or faeces), known colloquially and in slang as poo and poop, are the solid or semi-solid remains of food that was not digested in the small intestine, and has been broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Feces contain a relati ...

(waste product) of an infected person, including one with no apparent symptoms, can pass on the disease if it contacts the water supply by any means.

History does not recount any incidents of cholera until the 19th century. Cholera came in seven waves, the last two of which occurred in the 20th century.

The first cholera pandemic

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and reco ...

started in 1816, spread across India by 1820, and extended to Southeast Asia and Central Europe, lasting until 1826.

A second cholera pandemic

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

began in 1829, reached Russia, causing the Cholera riots

Cholera Riots refers to civil disturbances associated with an outbreak or epidemic of cholera.

In Russia

The Cholera Riots (''Холерные бунты'' in Russian) were the riots of the urban population, peasants and soldiers in 1830–183 ...

. It spread to Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

, Germany and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

in 1831, and London, Paris, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

, Ontario

Ontario ( ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada.Ontario is located in the geographic eastern half of Canada, but it has historically and politically been considered to be part of Central Canada. Located in Central Ca ...

and New York City the following year. Cholera reached the Pacific coast of North America by 1834, reaching into the center of the country by steamboat and other river traffic.

The third cholera pandemic

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

began in 1846 and lasted until 1860. It hit Russia hardest, with over one million deaths. In 1846, cholera struck Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

, killing over 15,000.Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846–63UCLA School of Public Health. A two-year outbreak began in

England and Wales

England and Wales () is one of the three legal jurisdictions of the United Kingdom. It covers the constituent countries England and Wales and was formed by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542. The substantive law of the jurisdiction is Eng ...

in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives. In 1849, outbreak occurred again in Paris, and in London, killing 14,137, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a h ...

survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever. In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the major port city of Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

, England, an embarkation point for immigrants to North America, and 1,834 in Hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* Chassis, of an armored fighting vehicle

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a ship

* Submarine hull

Mathematics

* Affine hull, in affi ...

, England. Cholera spread throughout the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

system. Thousands died in New York City, a major destination for Irish immigrants. Cholera killed 200,000 people in Mexico. That year, cholera was transmitted along the California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, Mormon

Mormons are a religious and cultural group related to Mormonism, the principal branch of the Latter Day Saint movement started by Joseph Smith in upstate New York during the 1820s. After Smith's death in 1844, the movement split into several ...

and Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what ...

s, killing people that are believed to have died on their way to the California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

, Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

and Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

in the cholera years of 1849–1855. In 1851, a ship coming from Cuba carried the disease to Gran Canaria, killing up to 6,000 people.

The pandemic spread east to Indonesia by 1852, and China and Japan in 1854. The Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

were infected in 1858 and Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

in 1859. In 1859, an outbreak in Bengal contributed to transmission of the disease by travelers and troops to Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

and Russia. Japan suffered at least seven major outbreaks of cholera between 1858 and 1902. The Ansei outbreak of 1858–60, for example, is believed to have killed between 100,000 and 200,000 people in Tokyo alone. An outbreak of cholera in Chicago in 1854 took the lives of 5.5% of the population (about 3,500 people). In 1853–4, London's epidemic claimed 10,738 lives. Throughout Spain, cholera caused more than 236,000 deaths in 1854–55. In 1854, it entered Venezuela; Brazil also suffered in 1855.

The

The fourth cholera pandemic

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'' (1972 film), a Sovie ...

(1863–1875) spread mostly in Europe and Africa. At least 30,000 of the 90,000 Mecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

pilgrims died from the disease. Cholera ravaged northern Africa in 1865 and southeastward to Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

, killing 70,000 in 1869–70. Cholera claimed 90,000 lives in Russia in 1866. The epidemic of cholera that spread with the Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

(1866) is estimated to have killed 165,000 people in the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

. In 1867, 113,000 died from cholera in Italy. and 80,000 in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

.

Outbreaks in North America in 1866–1873 killed some 50,000 Americans. In 1866, localized epidemics occurred in the East End of London, in southern Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

, and Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

. In the 1870s, cholera spread in the U.S. as an epidemic from New Orleans along the Mississippi River and to ports on its tributaries.

In the fifth cholera pandemic

Fifth is the ordinal form of the number five.

Fifth or The Fifth may refer to:

* Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as in the expression "pleading the Fifth"

* Fifth column, a political term

* Fifth disease, a contagious rash that ...

(1881–1896), according to Dr A. J. Wall, the 1883–1887 part of the epidemic cost 250,000 lives in Europe and at least 50,000 in the Americas. Cholera claimed 267,890 lives in Russia (1892); 120,000 in Spain; 90,000 in Japan and over 60,000 in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. In Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, cholera claimed more than 58,000 lives. The 1892 outbreak in Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

killed 8,600 people.

Smallpox

Smallpox is caused by either of the two viruses, Variola major and Variola minor. Smallpox vaccine was available in Europe, the United States, and the Spanish Colonies during the last part of the century. The Latin names of this disease are Variola Vera. The words come from various (spotted) or varus (pimple). In England, this disease was first known as the "pox" or the "red plague". Smallpox settles itself in small blood vessels of the skin and in the mouth and throat. The symptoms of smallpox are rash on the skin and blisters filled with raised liquid. The disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans annually during the 19th century and one-third of all the blindness of that time was caused by smallpox. 20 to 60% of all the people that were infected died and 80% of all the children with the infection also died. It caused also many deaths in the 20th century, over 300–500 million. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart also had smallpox when he was only 11 years old. He survived the smallpox outbreak in Austria.Typhus

Epidemic typhus is caused by the bacteria Rickettsia Prowazekii; it comes fromlice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a result o ...

. Murine typhus

Murine typhus, also known as endemic typhus or flea-borne typhus, is a form of typhus transmitted by fleas (''Xenopsylla cheopis''), usually on rats, in contrast to epidemic typhus which is usually transmitted by lice. Murine typhus is an under- ...

is caused by the Rickettsia Typhi bacteria, from the flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s on rats. Scrub typhus is caused by the Orientia Tsutsugamushi bacteria, from the harvest mite

Trombiculidae (); commonly referred to in North America as chiggers and in Britain as harvest mites, but also known as berry bugs, bush-mites, red bugs or scrub-itch mites, are a family of mites. Chiggers are often confused with jiggers – a t ...

s on humans and rodents. Queensland tick typhus

Queensland tick typhus is a zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium ''Rickettsia australis''.

It is transmitted by the ticks ''Ixodes holocyclus'' and '' Ixodes tasmani''.

Signs and symptoms

Queensland tick typhus is a tick-borne disease. Onse ...

is caused by the Rickettsia Australis bacteria, from tick

Ticks (order Ixodida) are parasitic arachnids that are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, species, and "fullness". Ticks are external parasites, living by ...

s.

During Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's retreat from Moscow in 1812, more French soldiers died of typhus than were killed by the Russians. A major epidemic occurred in Ireland between 1816 and 1819, during the Year Without a Summer

The year 1816 is known as the Year Without a Summer because of severe climate abnormalities that caused average global temperatures to decrease by . Summer temperatures in Europe were the extreme weather, coldest on record between the years of 1 ...

; an estimated 100,000 Irish perished. Typhus appeared again in the late 1830s, and between 1846 and 1849 during the Great Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a ...

. Spreading to England, and called "Irish fever", it was noted for its virulence. It killed people of all social classes, as lice were endemic and inescapable, but it hit particularly hard in the lower or "unwashed" social strata. In Canada alone, the typhus epidemic of 1847

The typhus epidemic of 1847 was an outbreak of epidemic typhus caused by a massive Irish emigration in 1847, during the Great Famine, aboard crowded and disease-ridden "coffin ships".

Canada

In Canada, more than 20,000 people died from 1847 to ...

killed more than 20,000 people from 1847 to 1848, mainly Irish immigrants in fever shed

A pest house, plague house, pesthouse or fever shed was a type of building used for persons afflicted with communicable diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera, smallpox or typhus. Often used for forcible quarantine, many towns and cities had one ...

s and other forms of quarantine, who had contracted the disease aboard coffin ships

A coffin ship () was any of the ships that carried Irish immigrants escaping the Great Irish Famine and Highlanders displaced by the Highland Clearances.

Coffin ships carrying emigrants, crowded and disease-ridden, with poor access to foo ...

. In the United States, epidemics occurred in Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Memphis and Washington DC between 1865 and 1873, and during the US Civil War.

Yellow fever

This disease is transmitted by the bite of female mosquito; the higher prevalence of transmission by

This disease is transmitted by the bite of female mosquito; the higher prevalence of transmission by Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its legs ...

has led to it being known as the Yellow Fever Mosquito. The transmission of yellow fever is entirely a matter of available habitat for vector mosquito and prevention such as mosquito netting. They mostly infect other primates, but humans can be infected. The symptoms of the fever are: Headaches, back and muscle pain, chills and vomiting, bleeding in the eyes and mouth, and vomit containing blood.

Yellow fever accounted for the largest number of the 19th-century's individual epidemic outbreaks, and most of the recorded serious outbreaks of yellow fever occurred in the 19th century. It is most prevalent in tropical-like climates, but the United States was not exempted from the fever. New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

was plagued with major epidemics during the 19th century, most notably in 1833 and 1853. At least 25 major outbreaks took place in the Americas during the 18th and 19th centuries, including particularly serious ones in Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 (Distrito Nacional)

, websi ...

in 1803 and Memphis in 1878. Major outbreaks occurred repeatedly in Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

; outbreaks in 1804, 1814, and again in 1828. Barcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

suffered the loss of several thousand citizens during an outbreak in 1821. Urban epidemics continued in the United States until 1905, with the last outbreak affecting New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

.

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Plague

The third plague pandemic was a majorbubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

pandemic

A pandemic () is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has spread across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. A widespread endemic (epidemiology), endemic disease wi ...

that began in Yunnan

Yunnan , () is a landlocked Provinces of China, province in Southwest China, the southwest of the People's Republic of China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 48.3 million (as of 2018). The capital of the province is ...

, China in 1855. This episode of bubonic plague spread to all inhabited continents in the 1890s and first years of the 1900s, and ultimately led to more than 12,000,000 deaths in India and China, with about 10,000,000 killed in India alone.

A natural reservoir of plague is located in western Yunnan and is an ongoing health risk today. The third pandemic of plague originated in this area after a rapid influx of Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

to exploit the demand for minerals, primarily copper, in the latter half of the 19th century. By 1850, the population had exploded to over 7,000,000 people. Increasing transportation throughout the region brought people in contact with plague-infected fleas, the primary vector between the yellow-breasted rat (''Rattus flavipectus'') and humans. The spread of European empires and the development of new forms of transport such as the steam engine made it easier for both humans and rats to spread the disease along existing trade routes.

Scarlet Fever

Haemolytic streptococcus, which was identified in the 1880s, causesscarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

, which is a bacterial disease. Scarlet fever spreads through respiratory droplets and children between the ages of 5 to 15 years were most affected by scarlet fever. Scarlet fever had several epidemic phases, and around 1825 to 1885 outbreaks began to recur cyclically and often highly fatal. In the mid-19th century, the mortality caused by scarlet fever rose in England and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. The major outbreak in England and Wales took place during 1825–1885 with high mortality marking this as remarkable. There were several other notable outbreaks across Europe, South America, and the United States in the 19th century.

United Kingdom

In the UK, scarlet fever was considered benign for two centuries, but fatal epidemics were seen in the 1700s. Scarlet fever broke out in England in the 19th century and was responsible for an enormous number of deaths in the 60-year period from 1825 to 1885; decades that followed had lower levels of annual mortality from scarlet fever. In NW England there was heavy mortality inLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

. Babies born in Liverpool with a birthday in 1861 were only expected to live 26 years, and in larger cities, life expectancy was less than 35 years. Over time, the life expectancy changed as well as the number of fatalities from scarlet fever. There was a reduction in child mortality from scarlet fever when you compare the decades, 1851–60 and 1891–1900. The decline of mortality seen for scarlet fever was noticed after the identification of streptococcus, but the decline was not associated with a treatment. A treatment would not be available until the introduction of sulphonamides in the 1930s, and the decline in mortality was due to the quality of air, food, and water improving. Outbreaks of scarlet fever also took place in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

in 1986 with 1,354 cases and 149 deaths, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

from 1862 to 1884, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

in 1861, and in the rest of United Kingdom. The United Kingdom saw cases in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

from 1839 to 1865 with 305 deaths, Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

in 1870 with 106 deaths and in 1875, and Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

in 1886 with six cases.

South America

Chile reported scarlet fever the first time in 1827 and highest rates were seen during winter months. The disease spread from Valparaiso toSantiago

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

from 1831 to 1832 and claimed 7,000 lives. There were multiple outbreaks in different locations of Chile, including Copaipo in 1875 and Caldera

A caldera ( ) is a large cauldron-like hollow that forms shortly after the emptying of a magma chamber in a volcano eruption. When large volumes of magma are erupted over a short time, structural support for the rock above the magma chamber is ...

in 1876.

United States

Similarly to Europe,America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

considered scarlet fever to be benign for two centuries. In the early 19th century the scarlet fever impact drastically changed and lethal epidemics started to arise in the United States. The United States had a notable outbreak of scarlet fever in Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

in 1847 and Augusta, Georgia

Augusta ( ), officially Augusta–Richmond County, is a consolidated city-county on the central eastern border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. The city lies across the Savannah River from South Carolina at the head of its navig ...

had a lethal epidemic in 1832–1833. Scarlet fever had low mortality rates in New York for many years before 1828, but remained high for long after. Cases of scarlet fever were also seen in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

during a period of decreasing severity after 1885. Boston City Hospital opened a scarlet fever pavilion in 1887 to house patients with infectious diseases and saw nearly 25,000 patients during 1895–1905. In the mid-1800s, more specific epidemiological information was emerging and incidence in infants were found to be low. In 1870, the US census showed a decrease in scarlet fever mortality in children below the age of one.

References

{{reflist * *19th

19 (nineteen) is the natural number following 18 and preceding 20. It is a prime number.

Mathematics

19 is the eighth prime number, and forms a sexy prime with 13, a twin prime with 17, and a cousin prime with 23. It is the third full re ...

Bacterial diseases

Intestinal infectious diseases

Smallpox

Epidemic typhus