Discovery of human antiquity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The discovery of human antiquity was a major achievement of science in the middle of the 19th century, and the foundation of scientific

Once the question is reformulated as dating the transition of the evolution of '' H. sapiens'' from a precursor species, the issue can be refined into two further questions. These are: the analysis and dating of the evolution of Archaic Homo sapiens, and of the evolution from "archaic" forms of the species '' H. sapiens sapiens''. The second question is given an answer in two parts: anatomically modern humans are thought to be about 300,000 years old, with

Once the question is reformulated as dating the transition of the evolution of '' H. sapiens'' from a precursor species, the issue can be refined into two further questions. These are: the analysis and dating of the evolution of Archaic Homo sapiens, and of the evolution from "archaic" forms of the species '' H. sapiens sapiens''. The second question is given an answer in two parts: anatomically modern humans are thought to be about 300,000 years old, with

There was interest in matters arising from modification of the biblical narrative, therefore, and it was fuelled by the new knowledge of the world in

There was interest in matters arising from modification of the biblical narrative, therefore, and it was fuelled by the new knowledge of the world in

paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship ...

. The antiquity of man, human antiquity, or in simpler language the age of the human race, are names given to the series of scientific debates it involved, which with modifications continue in the 21st century. These debates have clarified and given scientific evidence, from a number of disciplines, towards solving the basic question of dating the first human being

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedality, bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex Human brain, brain. This has enabled the development of ad ...

.

Controversy was very active in this area in parts of the 19th century, with some dormant periods also. A key date was the 1859 re-evaluation of archaeological evidence that had been published 12 years earlier by Boucher de Perthes

Boucher may refer to:

*Boucher (surname), a family name (including a list of people with that name)

* Boucher Manufacturing Company, an American toy company

*'' R. v. Boucher'', a 1951 Supreme Court of Canada decision that overturned a conviction ...

. It was then widely accepted, as validating the suggestion that man was much older than had previously been believed, for example than the 6,000 years implied by some traditional chronologies.

In 1863 T. H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

argued that man was an evolved species; and in 1864 Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

combined natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

with the issue of antiquity. The arguments from science for what was then called the "great antiquity of man" became convincing to most scientists, over the following decade. The separate debate on the antiquity of man had in effect merged into the larger one on evolution, being simply a chronological aspect. It has not ended as a discussion, however, since the current science of human antiquity is still in flux.

Contemporary formulations

Modern science has no single answer to the question of how old humanity is. What the question now means indeed depends on choosinggenus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

or species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

in the required answer. It is thought that the genus of man has been around for ten times as long as our species. Currently, fresh examples of (extinct) species of the genus ''Homo'' are still being discovered, so that definitive answers are not available. The consensus view is that human beings are one species, the only existing species of the genus. With the rejection of polygenism

Polygenism is a theory of human origins which posits the view that the human races are of different origins (''polygenesis''). This view is opposite to the idea of monogenism, which posits a single origin of humanity. Modern scientific views no ...

for human origins, it is asserted that this species had a definite and single origin in the past. (That assertion leaves aside the point whether the origin meant is of the current species, however. The multiregional hypothesis The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evoluti ...

allows the origin to be otherwise.) The hypothesis of recent African origin of modern humans

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans, also called the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA), recent single-origin hypothesis (RSOH), replacement hypothesis, or recent African origin model (RAO), is the dominant model of the ...

is now widely accepted, and states that anatomically modern humans

Early modern human (EMH) or anatomically modern human (AMH) are terms used to distinguish ''Homo sapiens'' (the only extant Hominina species) that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans from extin ...

had a single origin, in Africa.

The genus ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus ''Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely relate ...

'' is now estimated to be about 2.3 to 2.4 million years old, with the appearance of ''H. habilis

''Homo habilis'' ("handy man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.31 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, ''H. habilis'' was highly c ...

''; meaning that the existence of all types of humans has been within the Quaternary

The Quaternary ( ) is the current and most recent of the three periods of the Cenozoic Era in the geologic time scale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). It follows the Neogene Period and spans from 2.58 million years ...

.

behavioral modernity

Behavioral modernity is a suite of behavioral and cognitive traits that distinguishes current ''Homo sapiens'' from other anatomically modern humans, hominins, and primates. Most scholars agree that modern human behavior can be characterized by ...

dating back to 40,000 or 50,000 years ago. The first question is still subject to debates on its definition.

Historical debates

Discovering the age of the first human is one facet ofanthropogeny

Anthropogeny is the study of human origins. It is not simply a synonym for human evolution by natural selection, which is only a part of the processes involved in human origins. Many other factors besides natural selection were involved, ranging o ...

, the study of human origins, and a term dated by the ''Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

'' to 1839 and the ''Medical Dictionary'' of Robert Hooper. Given the history of evolutionary thought

Evolutionary thought, the recognition that species change over time and the perceived understanding of how such processes work, has roots in antiquity—in the ideas of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Church Fathers as well as in medie ...

, and the history of paleontology

The history of paleontology traces the history of the effort to understand the history of life on Earth by studying the fossil record left behind by living organisms. Since it is concerned with understanding living organisms of the past, paleonto ...

, the question of the antiquity of man became quite natural to ask at around this period. It was by no means a new question, but it was being asked in a new context of knowledge, particularly in comparative anatomy

Comparative anatomy is the study of similarities and differences in the anatomy of different species. It is closely related to evolutionary biology and phylogeny (the evolution of species).

The science began in the classical era, continuing in t ...

and palaeontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

. The development of relative dating

Relative dating is the science of determining the relative order of past events (i.e., the age of an object in comparison to another), without necessarily determining their absolute age (i.e., estimated age). In geology, rock or superficial dep ...

as a principled method allowed deductions of chronology relative to events tied to fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s and strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum ( : strata) is a layer of rock or sediment characterized by certain lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by visible surfaces known as ei ...

. This meant, though, that the issue of the antiquity of man was not separable from other debates of the period, on geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

and foundations of scientific archaeology.

The first strong scientific arguments for the antiquity of man as very different from accepted biblical chronology

The chronology of the Bible is an elaborate system of lifespans, 'generations', and other means by which the Masoretic Hebrew Bible (the text of the Bible most commonly in use today) measures the passage of events from the creation to around 164 ...

were certainly also strongly controverted. Those who found the conclusion unacceptable could be expected to examine the whole train of reasoning for weak points. This can be seen, for example, in the ''Systematic Theology'' of Charles Hodge

Charles Hodge (December 27, 1797 – June 19, 1878) was a Reformed Presbyterian theologian and principal of Princeton Theological Seminary between 1851 and 1878.

He was a leading exponent of the Princeton Theology, an orthodox Calvinist theol ...

(1871–3).

For a period, once the scale of geological time

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochronol ...

had become clear in the 19th century, the "antiquity of man" stood for a theory opposed to the "modern origin of man", for which arguments of other kinds were put forward. The choice was logically independent of monogenism versus polygenism; but monogenism with the modern origin implied time scales on the basis of the geographical spread, physical differences and cultural diversity

Cultural diversity is the quality of diverse or different cultures, as opposed to monoculture, the global monoculture, or a homogenization of cultures, akin to cultural evolution. The term "cultural diversity" can also refer to having different cu ...

of humans. The choice was also logically independent of the notion of transmutation of species

Transmutation of species and transformism are unproven 18th and 19th-century evolutionary ideas about the change of one species into another that preceded Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection. The French ''Transformisme'' was a term used ...

, but that was considered to be a slow process.

William Benjamin Carpenter

William Benjamin Carpenter CB FRS (29 October 1813 – 19 November 1885) was an English physician, invertebrate zoologist and physiologist. He was instrumental in the early stages of the unified University of London.

Life

Carpenter was born ...

wrote in 1872 of a fixed conviction of the "modern origin" as the only reason for resisting the human creation of flint implements. Henry Williamson Haynes writing in 1880 could call the antiquity of man "an established fact".

Theological debates

The Biblical account included *the story of theGarden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan-Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the Bible, biblical paradise described in Book of Genesis, Genes ...

and the descent of humans from a single couple;

*the story of the universal biblical Flood

The Genesis flood narrative (chapters 6–9 of the Book of Genesis) is the Hebrew version of the universal flood myth. It tells of God's decision to return the universe to its pre- creation state of watery chaos and remake it through the microc ...

, after which all humans descended from Noah and his wife, and all animals from those saved in the Ark;

*genealogies providing in theory a way of dating events in the Old Testament (see Genealogy of the Bible).

These points were debated by scholars as well as theologians. Biblical literalism

Biblical literalism or biblicism is a term used differently by different authors concerning biblical hermeneutics, biblical interpretation. It can equate to the dictionary definition of wikt:literalism, literalism: "adherence to the exact letter ...

was not a given in the medieval and early modern periods, for Christians or Jews.

Human origins and the "universal deluge" debated

The Flood could explain extinctions of species at that date, on the hypothesis that the Ark had not contained all species of animal. A Flood that was not universal, on the other hand, had implications for the biblical theory of races and Noah's sons. The theory ofcatastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow increment ...

, which was as much secular as theological in attitude, could be used in analogous ways.

There was interest in matters arising from modification of the biblical narrative, therefore, and it was fuelled by the new knowledge of the world in

There was interest in matters arising from modification of the biblical narrative, therefore, and it was fuelled by the new knowledge of the world in early modern Europe

Early modern Europe, also referred to as the post-medieval period, is the period of European history between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, roughly the late 15th century to the late 18th century. Histori ...

, and then by the growth of the sciences. One hypothesis was of people not descended from Adam. This hypothesis of polygenism (no unique origin of humans) implied nothing on the antiquity of man, but the issue was implicated in counter-arguments, for monogenism.

La Peyrère and the completeness of the Biblical account

Isaac La Peyrère Isaac La Peyrère (1596–1676), also known as Isaac de La Peyrère or Pererius, was a French-born theologian, writer, and lawyer. La Peyrère is best known as a 17th-century predecessor of the scientific racism, scientific racialist theory of polyg ...

appealed in formulating his Preadamite theory of polygenism to Jewish tradition; it was intended to be compatible with the biblical creation of man

The Genesis creation narrative is the creation myth of both Judaism and Christianity. The narrative is made up of two stories, roughly equivalent to the first two chapters of the Book of Genesis. In the first, Elohim (the Hebrew generic word f ...

. It was rejected by many contemporary theologians. This idea of humans before Adam had been current in earlier Christian scholars and those of unorthodox and heretical beliefs; La Peyrère's significance was his synthesis of the dissent. Influentially, he revived the classical idea of Marcus Terentius Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

, preserved in Censorinus

Censorinus was a Roman grammarian and miscellaneous writer from the 3rd century AD.

Biography

He was the author of a lost work ''De Accentibus'' and of an extant treatise ''De Die Natali'', written in 238, and dedicated to his patron Quintus ...

, of a three-fold division of historical time into "uncertain" (to a universal flood), "mythical", and "historical" (with certain chronology).

Debate on race

The biblical narrative had implications forethnology

Ethnology (from the grc-gre, ἔθνος, meaning 'nation') is an academic field that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them (compare cultural anthropology, cultural, social anthropolo ...

(division into Hamitic

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races which was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery. ...

, Japhetic

The term Japhetites (in adjective form Japhethitic or Japhetic) refers to the descendents of Japheth, one of the three sons of Noah in the Bible. The term has been adopted in ethnological and linguistic writing from the 18th to the 20th century ...

and Semitic peoples

Semites, Semitic peoples or Semitic cultures is an obsolete term for an ethnic, cultural or racial group.Matthew Hale wrote his ''Primitive Origination of Mankind'' (1677) against La Peyrère, it has been suggested, in order to defend the propositions of a young human race and universal Flood, and the Native Americans as descended from Noah. Anthony John Maas writing in the 1913 ''

Cave remains proved of great importance to the science of the antiquity of man.

Cave remains proved of great importance to the science of the antiquity of man.  The

The

Internet Archive

Postulating cultural change, in itself and without explaining a rate of change, did not generate reasons to revise traditional chronology. But the concept of The debate moved on only in the context of

*further

The debate moved on only in the context of

*further

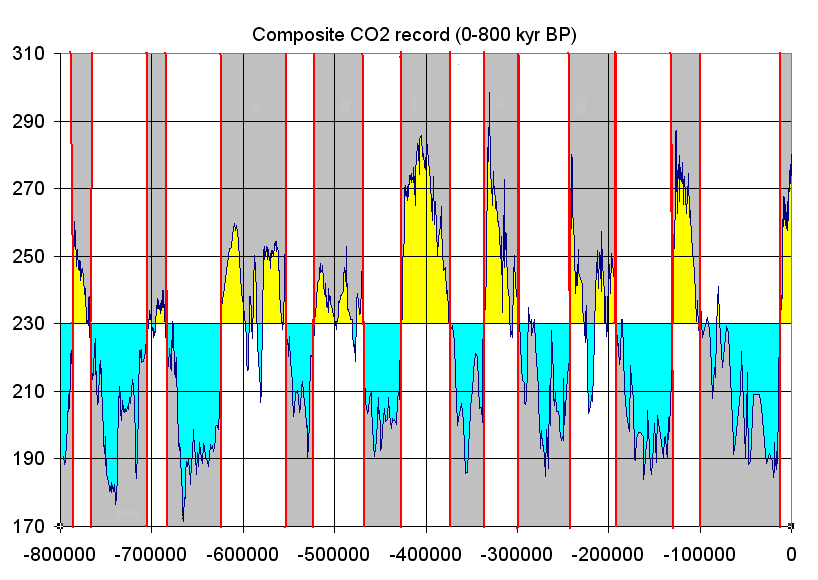

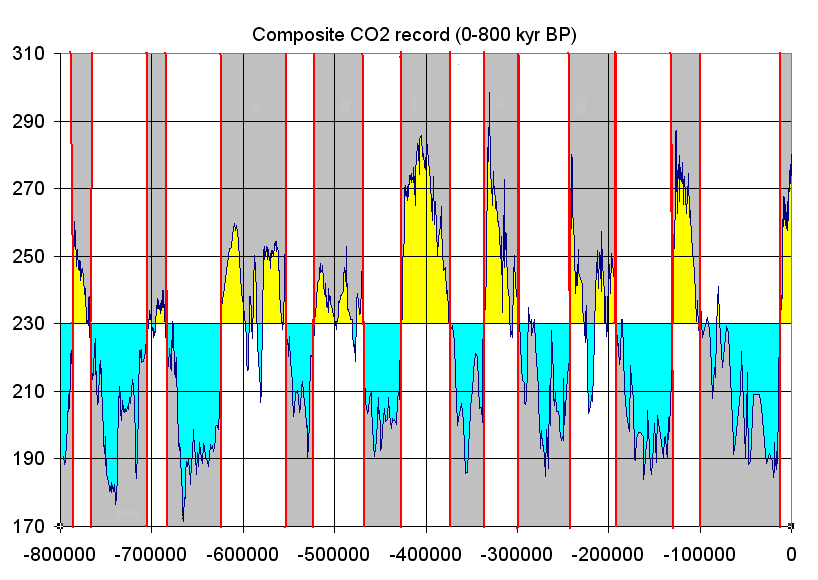

The identification of ice ages was important context for the antiquity of man because it was accepted that certain mammals had died out with the last of the ice ages; and the ice ages were clearly marked in the geological record.

The identification of ice ages was important context for the antiquity of man because it was accepted that certain mammals had died out with the last of the ice ages; and the ice ages were clearly marked in the geological record.  Given that the animals were associated with these strata, establishing the date of the strata could be by geological arguments, based on uniformity of stratigraphy; and so the animals' extinction was dated. An extinction can still strictly only be dated on assumptions, as evidence of absence; for a particular site, however, the argument can be from

Given that the animals were associated with these strata, establishing the date of the strata could be by geological arguments, based on uniformity of stratigraphy; and so the animals' extinction was dated. An extinction can still strictly only be dated on assumptions, as evidence of absence; for a particular site, however, the argument can be from

This debate was concurrent with that over the book ''

This debate was concurrent with that over the book ''

'Natural Selection' '' (1864)

*

Encyclopedia of Virginia Biography

/ref> ''The Epoch of the Mammoth and the Apparition of man upon the Earth'' (1878) *

Catholic Encyclopedia

The ''Catholic Encyclopedia: An International Work of Reference on the Constitution, Doctrine, Discipline, and History of the Catholic Church'' (also referred to as the ''Old Catholic Encyclopedia'' and the ''Original Catholic Encyclopedia'') i ...

'' commented that pro-slavery

Proslavery is a support for slavery. It is found in the Bible, in the thought of ancient philosophers, in British writings and in American writings especially before the American Civil War but also later through 20th century. Arguments in favor o ...

sentiment indirectly supported the Preadamite theories of the middle of the 19th century. The antiquity of man found support in the opposed theories of monogenism of this time that justified abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

by discrediting scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

.

Already in the 18th century polygenism was applied as a theory of race (see Scientific racism#Blumenbach and Buffon). A variant racist Preadamism was introduced, in particular by Reginald Stuart Poole

Reginald Stuart Poole (27 January 18328 February 1895), known as Stuart Poole, was an English archaeologist, numismatist and Orientalist. Poole was from a famous Orientalist family as his mother Sophia Lane Poole, his uncle Edward William Lane and ...

(''The Genesis of the Earth and of Man'', London, 1860) and Dominic M'Causland (''Adam and the Adamite, or the Harmony of Scripture and Ethnology'', London, 1864). They followed the views of Samuel George Morton

Samuel George Morton (January 26, 1799 – May 15, 1851) was an American physician, natural scientist, and writer who argued against the single creation story of the Bible, monogenism, instead supporting a theory of multiple racial creations, poly ...

, Josiah C. Nott

Josiah Clark Nott (March 31, 1804March 31, 1873) was an American surgeon and anthropologist. He is known for his studies into the etiology of yellow fever and malaria, including the theory that they originate from germs.

Nott, who owned slaves ...

, George Gliddon

George Robbins Gliddon (1809 – November 16, 1857) was an English-born American Egyptologist.

Biography

He was born in Devonshire, England. His father, a merchant, was United States consul at Alexandria where Gliddon was taken at an early age. ...

, and Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz ( ; ) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

Spending his early life in Switzerland, he rec ...

; and maintained that Adam was the progenitor of the Caucasian race

The Caucasian race (also Caucasoid or Europid, Europoid) is an obsolete racial classification of human beings based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. The ''Caucasian race'' was historically regarded as a biological taxon which, de ...

, while the other races descended from Preadamite ancestry.

James Cowles Prichard

James Cowles Prichard, FRS (11 February 1786 – 23 December 1848) was a British physician and ethnologist with broad interests in physical anthropology and psychiatry. His influential ''Researches into the Physical History of Mankind'' touched ...

argued against polygenism, wishing to support the account drawn from the ''Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek ; Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, ( "In the beginning") ...

'' of a single human origin. In particular he argued that humans were one species, using the interfertility

In biology, a hybrid is the offspring resulting from combining the qualities of two organisms of different breeds, varieties, species or genera through sexual reproduction. Hybrids are not always intermediates between their parents (such as in ...

criterion of hybridity Hybridity, in its most basic sense, refers to mixture. The term originates from biology and was subsequently employed in linguistics and in racial theory in the nineteenth century. Young, Robert. ''Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and R ...

. By his use of a form of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

to argue for change of human skin colour

Human skin color ranges from the darkest brown to the lightest hues. Differences in skin color among individuals is caused by variation in pigmentation, which is the result of genetics (inherited from one's biological parents and or individu ...

as a historical process, he also implied a time scale long enough for such a process to have produced the observed differences.

Incompatible views of chronology

TheEarly Christian Church

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

contested claims that pagan traditions were older than that of the Bible. Theophilus of Antioch

:''There is also a Theophilus of Alexandria'' (c. 412 AD).

Theophilus ( el, Θεόφιλος ὁ Ἀντιοχεύς) was Patriarch of Antioch from 169 until 182. He succeeded Eros c. 169, and was succeeded by Maximus I c. 183, according to Henr ...

and Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North Af ...

both argued against Egyptian views that the world was at least 100,000 years old. This figure was too high to be compatible with biblical chronology. One of La Peyrère's propositions, that China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

was at least 10,000 years old, gained wider currency; Martino Martini

Martino Martini () (20 September 1614 – 6 June 1661), born and raised in Trento (Prince-Bishopric of the Holy Roman Empire), was a Jesuit missionary. As cartographer and historian, he mainly worked on ancient Imperial China.

Early years

Mart ...

had provided details of traditional Chinese chronology, from which it was deduced by Isaac Vossius

Isaak Vossius, sometimes anglicised Isaac Voss (1618 in Leiden – 21 February 1689 in Windsor, Berkshire) was a Dutch scholar and manuscript collector.

Life

He was the son of the humanist Gerhard Johann Vossius. Isaak formed what was accoun ...

that Noah's Flood was local rather than universal.

One of the considerations detected in La Peyrère by Otto Zöckler

Otto Zöckler (27 May 1833, Grünberg, Hesse – 19 February 1906) was a German theologian, professor at Greifswald

Greifswald (), officially the University and Hanseatic City of Greifswald (german: Universitäts- und Hansestadt Greifswald, Lo ...

was concern with the Antipodes

In geography, the antipode () of any spot on Earth is the point on Earth's surface diametrically opposite to it. A pair of points ''antipodal'' () to each other are situated such that a straight line connecting the two would pass through Ear ...

and their people: were they pre-Adamites, or indeed had there been a second "Adam of the Antipodes"? In a 19th-century sequel, Alfred Russel Wallace in an 1867 book review pointed to the Pacific Islanders

Pacific Islanders, Pasifika, Pasefika, or rarely Pacificers are the peoples of the Pacific Islands. As an ethnic/racial term, it is used to describe the original peoples—inhabitants and diasporas—of any of the three major subregions of Ocea ...

as posing a problem for those holding both to monogenism and a recent date for human origins. In other words, he took migration from an original location to remote islands that are now populated to imply a long time scale. A significant consequence of the recognition of the antiquity of man was the greater scope for conjectural history Conjectural history is a type of historiography isolated in the 1790s by Dugald Stewart, who termed it "theoretical or conjectural history," as prevalent in the historians and early social scientists of the Scottish Enlightenment. As Stewart saw it, ...

, in particular for all aspects of diffusionism

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technolo ...

and social evolutionism

Sociocultural evolution, sociocultural evolutionism or social evolution are theories of sociobiology and cultural evolution that describe how Society, societies and culture change over time. Whereas sociocultural development traces processes th ...

.

Creation of man in a world not ready

While extinction of species came with the development of geology to be widely accepted in the early 19th century, there was resistance on theological grounds to extinctions after the creation of man. It was argued, in particular in the 1820s and 1830s, that man would not be created into an "imperfect" world as far as design of its collection of species was concerned. This reasoning cut across that which was conclusive for the science of the antiquity of man, a generation later.Archaeological context

The late 18th century was a period in which French and German caves were explored, and remains taken for study:caving

Caving – also known as spelunking in the United States and Canada and potholing in the United Kingdom and Ireland – is the recreational pastime of exploring wild cave systems (as distinguished from show caves). In contrast, speleology i ...

was in fashion, if speleology

Speleology is the scientific study of caves and other karst features, as well as their make-up, structure, physical properties, history, life forms, and the processes by which they form (speleogenesis) and change over time (speleomorphology). ...

was only in its infancy, and the St. Beatus Caves

Beatus of Lungern, known also by the honorific Apostle of Switzerland or as Beatus of Beatenberg or Beatus of Thun, was probably a legendary monk and hermit of early Christianity, and is revered as a saint. Though his legend states that he died in ...

, for example, attracted many visitors. Caves were a theme of the art of the time, also. Cave remains proved of great importance to the science of the antiquity of man.

Cave remains proved of great importance to the science of the antiquity of man. Stalagmite

A stalagmite (, ; from the Greek , from , "dropping, trickling")

is a type of rock formation that rises from the floor of a cave due to the accumulation of material deposited on the floor from ceiling drippings. Stalagmites are typically ...

formation was a clearcut mechanism of formation of fossils, and its stratigraphy could be understood. Other sites of importance were associated with alluvial deposit

Alluvium (from Latin ''alluvius'', from ''alluere'' 'to wash against') is loose clay, silt, sand, or gravel that has been deposited by running water in a stream bed, on a floodplain, in an alluvial fan or beach, or in similar settings. Alluv ...

s of gravel and clay, or peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

. The early example of the Gray's Inn Lane Hand Axe

The Gray's Inn Lane Hand Axe is a pointed flint hand axe, found buried in gravel under Gray's Inn Lane, London, England, by pioneering archaeologist John Conyers in 1679, and now in the British Museum. The hand axe is a fine example from about ...

was from gravel in a bed of a tributary of the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

, but remained isolated for about a century.

The

The three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human pre-history (with some overlap into the historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age; although the concept may also refer to o ...

was in place from about 1820, in the form given to it by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen

Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (29 December 1788 – 21 May 1865) was a Danish antiquarian who developed early archaeological techniques and methods.

In 1816 he was appointed head of 'antiquarian' collections which later developed into the Nati ...

in his work on the collections that became the National Museum of Denmark

The National Museum of Denmark (Nationalmuseet) in Copenhagen is Denmark's largest museum of cultural history, comprising the histories of Danish and foreign cultures, alike. The museum's main building is located a short distance from Strøget ...

. He published his ideas in 1836.Grahame Clark, ''The Identity of Man: as seen by an archaeologist'' (1983), p. 48Internet Archive

Postulating cultural change, in itself and without explaining a rate of change, did not generate reasons to revise traditional chronology. But the concept of

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

artifacts became current. Thomsen's book in Danish, ''Ledetraad til Nordisk Oldkyndighed'', was translated into German (''Leitfaden zur Nordischen Alterthumskunde'', 1837), and English (''Guide to Northern Archæology'', 1848).

John Frere

John Frere (10 August 1740 – 12 July 1807) was an English antiquary and a pioneering discoverer of Old Stone Age or Lower Palaeolithic tools in association with large extinct animals at Hoxne, Suffolk in 1797.

Life

Frere was born in Royd ...

's 1797 discovery of the Hoxne handaxeFrere, John, , in ''Archaeologia'', v. 13 (London, 1800): 204–205 helped to initiate the 19th century debate, but it started in earnest around 1810. There were then a number of false starts relating to different European sites. William Buckland

William Buckland Doctor of Divinity, DD, Royal Society, FRS (12 March 1784 – 14 August 1856) was an English theologian who became Dean of Westminster. He was also a geologist and paleontology, palaeontologist.

Buckland wrote the first full ...

misjudged what he had found in 1823 with the misnamed Red Lady of Paviland

The Red Lady of Paviland is an Upper Paleolithic partial skeleton of a male dyed in red ochre and buried in Wales 33,000 BP. The bones were discovered in 1823 by William Buckland in an archaeological dig at Goat's Hole Cave (Paviland cave) – ...

, and explained away the mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

remains with the find. He also was dismissive of the Kent's Cavern

Kents Cavern is a cave system in Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable for its archaeological and geological features. The cave system is open to the public and has been a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest since 1952 and a Schedu ...

findings of John MacEnery

John MacEnery (27 November 1796 – 18 February 1841) was a Roman Catholic priest from Limerick, Ireland and early archaeologist who came to Devon as Chaplain to the Cary family at Torre Abbey in 1822. In 1825, 1826 and 1829, he investigated the ...

in the later 1820s. In 1829 Philippe-Charles Schmerling

Philippe-Charles or Philip Carel Schmerling (2 March 1791 Delft – 7 November 1836, Liège) was a Dutch/Belgian prehistorian, pioneer in paleontology, and geologist. He is often considered the founder of paleontology.

In 1829 he discovered ...

discovered a Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

fossil skull (at Engis

Engis (; wa, Indji) is a municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium.

On 1 January 2006 Engis had a total population of 5,686. The total area is 27.74 km² which gives a population density of 205 inhabitants per km� ...

). At that point, however, its significance was not recognised, and Rudolf Virchow

Rudolf Ludwig Carl Virchow (; or ; 13 October 18215 September 1902) was a German physician, anthropologist, pathologist, prehistorian, biologist, writer, editor, and politician. He is known as "the father of modern pathology" and as the founder ...

consistently opposed the theory that it was very old. The 1847 book ''Antiquités Celtiques et Antediluviennes'' by Boucher de Perthes about Saint-Acheul

Saint-Acheul is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France. It is not to be confused with Saint-Acheul, a suburb of Amiens after which the Acheulean archaeological culture of the Lower Paleolithic is named.

Geograph ...

was found unconvincing in its presentation, until it was reconsidered about a decade later.

The debate moved on only in the context of

*further

The debate moved on only in the context of

*further stone tools

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric (particularly Stone Ag ...

that were admitted to be made by Stone Age man, found

*on sites where the stratigraphy could be argued to be clear and undisturbed, with

*remains of animals that were (in the consensus of palaeontologists) now extinct.

It was this combination, "extinct faunal remains" + "human artifacts", that provided the evidence that came to be seen as crucial. A sudden acceleration of research was seen from mid-1858, when the Geological Society

The Geological Society of London, known commonly as the Geological Society, is a learned society based in the United Kingdom. It is the oldest national geological society in the world and the largest in Europe with more than 12,000 Fellows.

Fe ...

set up a "cave committee". Besides Hugh Falconer

Hugh Falconer MD FRS (29 February 1808 – 31 January 1865) was a Scottish geologist, botanist, palaeontologist, and paleoanthropologist. He studied the flora, fauna, and geology of India, Assam,Burma,and most of the Mediterranean islands ...

who had pressed for it, the committee comprised Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

, Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, William Pengelly

William Pengelly, Royal Society, FRS Geological Society, FGS (12 January 1812 – 16 March 1894) was a British geologist and amateur archaeologist who was one of the first to contribute proof that the Biblical chronology of the earth calculated ...

, Joseph Prestwich

Sir Joseph Prestwich, FRS (12 March 1812 – 23 June 1896) was a British geologist and businessman, known as an expert on the Tertiary Period and for having confirmed the findings of Boucher de Perthes of ancient flint tools in the Somme valle ...

, and Andrew Ramsay.

Debate on uniformity and change

On the one hand, lack of uniformity inprehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

is what gave science traction on the question of the antiquity of man; and, on the other hand, there were at the time theories that tended to rule out certain types of lack of regularity. John Lubbock outlined in 1890 the way the antiquity of man had in his time been established as derived from change in prehistory: in fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

, geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

and climate

Climate is the long-term weather pattern in an area, typically averaged over 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorologic ...

. The hypotheses required to establish that these changes were facts of prehistory were themselves in tension with the uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

that was held to by some scientists; therefore the protean concept "uniformitarianism" was adjusted to accommodate the past changes that could be established.

Zoological uniformity on earth was debated already in the early eighteenth century.

George Berkeley

George Berkeley (; 12 March 168514 January 1753) – known as Bishop Berkeley (Bishop of Cloyne of the Anglican Church of Ireland) – was an Anglo-Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immate ...

argued in ''Alciphron

Alciphron ( grc-gre, Ἀλκίφρων) was an ancient Greek sophist, and the most eminent among the Greek epistolographers. Regarding his life or the age in which he lived we possess no direct information whatsoever.

Works

We possess under the ...

'' that the lack of human artifacts in deeper excavations suggested a recent origin of man. Evidence of absence

Evidence of absence is evidence of any kind that suggests something is missing or that it does not exist. What counts as evidence of absence has been a subject of debate between scientists and philosophers. It is often distinguished from absence o ...

was, of course, seen as problematic to establish. Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

in his ''Protogaea

''Protogaea'' is a work by Gottfried Leibniz on geology and natural history. Unpublished in his lifetime, but made known by Johann Georg von Eckhart in 1719, it was conceived as a preface to his incomplete history of the House of Brunswick.

Lif ...

'' produced arguments against identification of a species via morphology

Morphology, from the Greek and meaning "study of shape", may refer to:

Disciplines

* Morphology (archaeology), study of the shapes or forms of artifacts

* Morphology (astronomy), study of the shape of astronomical objects such as nebulae, galaxies ...

, without evidence of descent (having in mind a characterisation of humans by possession of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

); and against the discreteness of species and their extinction.

Uniformitarianism held the field against the competitor theories of Neptunism

Neptunism is a superseded scientific theory of geology proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817) in the late 18th century, proposing that rocks formed from the crystallisation of minerals in the early Earth's oceans.

The theory took its na ...

and catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow increment ...

, which partook of Romantic science and theological cosmogony; it established itself as the successor of Plutonism

Plutonism is the geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on the sea bed, re- ...

, and became the foundation of modern geology. Its tenets were correspondingly firmly held. Charles Lyell

Sir Charles Lyell, 1st Baronet, (14 November 1797 – 22 February 1875) was a Scottish geologist who demonstrated the power of known natural causes in explaining the earth's history. He is best known as the author of ''Principles of Geolo ...

put forward at one point views on what were called "uniformity of kind" and "uniformity of degree" that were incompatible with what was argued later. Lyell's theory, in fact, was of a "steady state" geology, which he deduced from his principles. This went too far in restricting actual geological processes, to a predictable closed system

A closed system is a natural physical system that does not allow transfer of matter in or out of the system, although — in contexts such as physics, chemistry or engineering — the transfer of energy (''e.g.'' as work or heat) is allowed.

In ...

, if it ruled out ice ages

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

(see ice ages#Causes of ice ages), as became clearer not long after Lyell's ''Principles of Geology

''Principles of Geology: Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth's Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation'' is a book by the Scottish geologist Charles Lyell that was first published in 3 volumes from 1830–1833. Ly ...

'' appeared (1830–3). Of Lubbock's three types of change, the geographical included the theory of migration over land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and Colonisation (biology), colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regre ...

s in biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems in geographic space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities often vary in a regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, ...

, which in general acted as an explanatory stopgap, rather than in most cases being one supported by science. Sea level changes were easier to justify.

Glacial conditions

The identification of ice ages was important context for the antiquity of man because it was accepted that certain mammals had died out with the last of the ice ages; and the ice ages were clearly marked in the geological record.

The identification of ice ages was important context for the antiquity of man because it was accepted that certain mammals had died out with the last of the ice ages; and the ice ages were clearly marked in the geological record. Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, Baron Cuvier (; 23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier, was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuvier ...

's ''Recherches sur les ossements fossiles de quadrupèdes'' (1812) had made accepted facts of the extinctions of mammals that were to be relevant to human antiquity. The concept of an ice age was proposed in 1837 by Louis Agassiz, and it opened the way to the study of glacial history of the Quaternary. William Buckland came to see evidence of glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its Ablation#Glaciology, ablation over many years, often Century, centuries. It acquires dis ...

s in what he had taken to be remains of the biblical Flood. It seemed adequately proved that the woolly mammoth

The woolly mammoth (''Mammuthus primigenius'') is an extinct species of mammoth that lived during the Pleistocene until its extinction in the Holocene epoch. It was one of the last in a line of mammoth species, beginning with '' Mammuthus subp ...

and woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a me ...

were mammals of the ice ages, and had ceased to exist with the ice ages: they inhabited Europe when it was tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

, and not afterwards. In fact such extinct mammals were typically found in ''diluvium'' as it was then called (distinctive gravel or boulder clay

Boulder clay is an unsorted agglomeration of clastic sediment that is unstratified and structureless and contains gravel of various sizes, shapes, and compositions distributed at random in a fine-grained matrix. The fine-grained matrix consists ...

).

Given that the animals were associated with these strata, establishing the date of the strata could be by geological arguments, based on uniformity of stratigraphy; and so the animals' extinction was dated. An extinction can still strictly only be dated on assumptions, as evidence of absence; for a particular site, however, the argument can be from

Given that the animals were associated with these strata, establishing the date of the strata could be by geological arguments, based on uniformity of stratigraphy; and so the animals' extinction was dated. An extinction can still strictly only be dated on assumptions, as evidence of absence; for a particular site, however, the argument can be from local extinction

Local extinction, also known as extirpation, refers to a species (or other taxon) of plant or animal that ceases to exist in a chosen geographic area of study, though it still exists elsewhere. Local extinctions are contrasted with global extinct ...

.

Neither Agassiz nor Buckland adopted the new views on the antiquity of man.

Acceptance of human association with extinct animal species

Boucher de Perthes had written up discoveries in theSomme valley

The Somme ( , , ) is a river in Picardy, northern France.

The river is in length, from its source in the high ground of the former at Fonsomme near Saint-Quentin, to the Bay of the Somme, in the English Channel. It lies in the geological ...

in 1847. Joseph Prestwich and John Evans in April 1859, and Charles Lyell with others also in 1859, made field trips to the sites, and returned convinced that humans had coexisted with extinct mammals. In general and qualitative terms, Lyell felt the evidence established the "antiquity of man": that humans were much older than the traditional assumptions had made them. His conclusions were shared by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

and other British learned institutions, as well as in France. It was this recognition of the early date of Acheulean handaxe

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

s that first established the scientific credibility of the ''deep'' antiquity of humans.

This debate was concurrent with that over the book ''

This debate was concurrent with that over the book ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'', published in 1859, and was evidently related; but was not one in which Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

initially made his own views public. Consolidation of the "antiquity of man" required more work, with stricter methods; and this proved possible over the next two decades. The discoveries of Boucher de Perthes therefore motivated further researches to try to repeat and confirm the findings at other sites. Significant in this were excavations by William Pengelly

William Pengelly, Royal Society, FRS Geological Society, FGS (12 January 1812 – 16 March 1894) was a British geologist and amateur archaeologist who was one of the first to contribute proof that the Biblical chronology of the earth calculated ...

at Brixham Cavern, and with a systematic approach at Kents Cavern

Kents Cavern is a cave system in Torquay, Devon, England. It is notable for its archaeological and geological features. The cave system is open to the public and has been a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest since 1952 and a Schedule ...

(1865–1880). Another major project, which produced quicker findings, was that of Henry Christy

Henry Christy (26 July 1810 – 4 May 1865) was an English banker and collector, who left his substantial collections to the British Museum.

Early life

Christy was born at Kingston upon Thames, the second son of William Miller Christy of Woodbin ...

and Édouard Lartet

Édouard Lartet (15 April 180128 January 1871) was a French geologist and paleontologist, and a pioneer of Paleolithic archaeology.

Biography

Lartet was born near Castelnau-Barbarens, ' of Gers, France, where his family had lived for more than ...

. Lartet in 1860 had published results from a cave near Massat

Massat () is a commune in the Ariège department in southwestern France.

It is situated on the former Route nationale 618, the "Route of the Pyrenees".

History

The area dates back to paleolithic times, when tribes left some traces in painte ...

( Ariège) claiming stone tool cuts on bones of extinct mammals, made when the bones were fresh.

List of key sites for the 19th century debate

Further issues

Antiquity of man in the New World

Tertiary Man

When the science was considered reasonably settled as to the existence of "Quaternary Man" (humans of thePleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

), there remained the issue as to whether man had existed in the Tertiary

Tertiary ( ) is a widely used but obsolete term for the geologic period from 66 million to 2.6 million years ago.

The period began with the demise of the non-avian dinosaurs in the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, at the start ...

, a now obsolete term used for the preceding geological period. The debate on the antiquity of man resonated in the later debate over eolith

An eolith (from Greek "''eos''", dawn, and "''lithos''", stone) is a knapped flint nodule. Eoliths were once thought to have been artifacts, the earliest stone tools, but are now believed to be geofacts (stone fragments produced by fully natur ...

s, which were supposed proof of the existence of man in the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Neogene

The Neogene ( ), informally Upper Tertiary or Late Tertiary, is a geologic period and system that spans 20.45 million years from the end of the Paleogene Period million years ago ( Mya) to the beginning of the present Quaternary Period Mya. ...

). In this case the sceptical view won out.

Publications

Publications of the central years of the debate

*Édouard Lartet

Édouard Lartet (15 April 180128 January 1871) was a French geologist and paleontologist, and a pioneer of Paleolithic archaeology.

Biography

Lartet was born near Castelnau-Barbarens, ' of Gers, France, where his family had lived for more than ...

, ''The Antiquity of Man in Western Europe'' (1860)

*——, ''New Researches on the Coexistence of Man and of the Great Fossil Mammifers characteristic of the Last Geological Period'' (1861)

*Charles Lyell, ''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man

''Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man'' is a book written by British geologist, Charles Lyell in 1863. The first three editions appeared in February, April, and November 1863, respectively. A much-revised fourth edition appeared in 18 ...

'' (1863). It was a major synthesis that discussed the issue of human antiquity, in parallel with the further issues of the Ice Ages and human evolution

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of ''Homo sapiens'' as a distinct species of the hominid family, which includes the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of ...

that promised to throw light on the origins of man.

*T. H. Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley (4 May 1825 – 29 June 1895) was an English biologist and anthropologist specialising in comparative anatomy. He has become known as "Darwin's Bulldog" for his advocacy of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution.

The stor ...

, ''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature

''Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature'' is an 1863 book by Thomas Henry Huxley, in which he gives evidence for the evolution of humans and apes from a common ancestor. It was the first book devoted to the topic of human evolution, and discussed ...

'' (1863)

*Alfred Russel Wallace, ''The Origin of Human Races and the Antiquity of Man Deduced from the Theory of James Geikie

James Murdoch Geikie PRSE FRS LLD (23 August 1839 – 1 March 1915) was a Scottish geologist. He was professor of geology at Edinburgh University from 1882 to 1914.

Life

Education

He was born in Edinburgh, the son of James Stuart Geikie a ...

, ''The Great Ice Age and its Relation to the Antiquity of Man'' (1874).

Publications of the latter stages of the debate

*John Patterson MacLean

John Patterson MacLean (March 12, 1848 – August 12, 1939) was an American Universalist minister and archaeologist and historian. While at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a pub ...

, ''A Manual of the Antiquity of Man'' (1877)

*James Cocke Southall,/ref> ''The Epoch of the Mammoth and the Apparition of man upon the Earth'' (1878) *

William Boyd Dawkins

Sir William Boyd Dawkins (26 December 183715 January 1929) was a British geologist and archaeologist. He was a member of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, Curator of the Manchester Museum and Professor of Geology at Owens College, Manc ...

, ''Early Man in Britain and His Place in the Tertiary Period'' (1880)

*Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and paleontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkable gift for interpreting fossils.

Owe ...

, ''Antiquity of Man as deduced from the Discovery of a Human Skeleton during Excavations of the Docks at Tilbury'' (1884)

*George Frederick Wright

George Frederick Wright (January 22, 1838 – April 20, 1921) was an American geologist and a professor at Oberlin Theological Seminary, first of New Testament language and literature (1881 – 1892), and then of "harmony of science and revelati ...

, ''The Ice Age in North America, and its Bearings upon the Antiquity of Man'' (1889)

*George Grant MacCurdy

George Grant MacCurdy (April 17, 1863 – November 15, 1947) was an American anthropologist, born at Warrensburg, Mo., where he graduated from the State Normal School in 1887, after which he attended Harvard (AB, 1893; AM, 1894); then studied in ...

, ''Recent Discoveries Bearing on the Antiquity of Man in Europe'' (1910)

*George Frederick Wright

George Frederick Wright (January 22, 1838 – April 20, 1921) was an American geologist and a professor at Oberlin Theological Seminary, first of New Testament language and literature (1881 – 1892), and then of "harmony of science and revelati ...

, ''Origin and Antiquity of Man'' (1912)

*Arthur Keith

Sir Arthur Keith FRS FRAI (5 February 1866 – 7 January 1955) was a British anatomist and anthropologist, and a proponent of scientific racism. He was a fellow and later the Hunterian Professor and conservator of the Hunterian Museum of the R ...

, ''The Antiquity of Man'' (1915)

See also

*Tool use by animals

Tool use by animals is a phenomenon in which an animal uses any kind of tool in order to achieve a goal such as acquiring food and water, grooming, defence, communication, recreation or construction. Originally thought to be a skill possessed o ...

*List of first human settlements

This is a list of dates associated with the prehistoric peopling of the world (first known presence of ''Homo sapiens'').

The list is divided into four categories, Middle Paleolithic (before 50,000 years ago),

Upper Paleolithic (50,000 to 12,500 ...

References and sources

;References ;Sources *{{CE1913, wstitle=Preadamites Paleoanthropology History of science