Dino Segre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Pitigrilli was the

Pitigrilli was the

p. 356. Picador, 1991 (reissued by Macmillan, 2003) Stille noted that the Fascist secret police used intelligence from these conversations to arrest and prosecute anti-fascist Jewish friends and relatives of Pitigrilli. Stille used many documents and accounts by members of the clandestine anti-fascist movement Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Freedom) operating in Turin. An Italian post-war government committee investigating collaborators and OVRA concluded about the writer: "…the last doubt (on Pitigrilli being OVRA informant number 373) could not stand after the unequivocal and categorical testimonies … about encounters and confidential conversations that took place exclusively with Pitigrilli."

Hathi Trust Digital Library, University of California, accessed 23 June 2013 * ''La Donna di 30, 40, 50, 60 Anni'' (1967) * ''L'Ombelico di Adamo. Peperoni dolci'' (1970) * ''Sette delitti'' (1971) * ''Nostra Signora di Miss Tif'' (1974)

New Vessel Press

Angiolo Paschetta, ''Il fenomeno Pitigrilli''

, Torino: Casa Editrice Sfinge, 1922, text online at Hathi Trust Digital Library, University of California {{Authority control 1893 births 1975 deaths Writers from Turin Italian male writers University of Turin alumni Italian spies Jewish Italian writers

Pitigrilli was the

Pitigrilli was the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

of Dino Segre, (9 May 1893 - 8 May 1975), an Italian writer who made his living as a journalist and novelist. His most noted novel was ''Cocaina'' (Cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly recreational drug use, used recreationally for its euphoria, euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from t ...

) (1921), published under his pseudonym and placed on the list of prohibited books by the Catholic Church because of his treatment of drug use and sex. It has been translated into several languages and re-issued in several editions. Pitigrilli published novels up until 1974, the year before his death.

He founded the literary magazine '' Grandi Firme,'' which was published in Turin from 1924 to 1938, when it was banned under the anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

Race Laws of the Fascist government. Although baptized a Catholic, Segre was classified as Jewish at that time. His father was Jewish, and Pitigrilli had married a Jewish woman (although they had long lived apart). He had worked in the 1930s as an informant for OVRA

The OVRA, whose most probable name was Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism ( it, Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Repressione dell'Antifascismo), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy, founded in 1927 under the ...

, the Fascist secret service, but was dismissed in 1939 after being exposed in Paris.

Pitigrilli had traveled in Europe in the 1930s while maintaining his house in Turin. His efforts, beginning in 1938, to change his racial status were not successful, and he was interned as a Jew in 1940, after Italy's entrance into the war as an ally of Germany. He was released the same year, and wrote anonymously in Rome to earn money. After Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

's government fell in 1943 and the Germans began to occupy Italy, Pitigrilli fled to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where his second wife (a Catholic) and their daughter joined him. They lived there until 1947, then moved to Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

. Segre and his family returned to Europe in 1958 and settled in Paris, occasionally visiting Turin.

Biography

Early life and family

Dino Segre was born inTurin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

. His mother was Catholic and father was Jewish; he was baptized a Catholic. He went to local schools and to the University of Turin, Faculty of Law

The University of Turin Department of Law is the law school of the University of Turin.

It is commonly shortened ''UNITO Department of Law''.

It traces its roots to the founding of the University of Turin, and has produced or hosted some of the m ...

, where he graduated in 1916. After university he spent time among literary and art circles in Paris.

Segre had a short-lived relationship with the poet Amalia Guglielminetti

Amalia Guglielminetti (4 April 1881 – 4 December 1941) was an Italian poet and writer.

Life

Amalia, who had two sisters, Emma and Erminia, and a brother, Ernesto, was born in Turin to Pietro Guglielminetti and his wife Felicita Lavezzato. He ...

. In 1932 he married a Jewish woman after she became pregnant during their relationship. They married outside the Catholic Church. They had one son, Gianni Segre. By the late 1930s they had long been separated and were living apart, but there was no divorce in Italy.

It was Pitigrilli's marriage to a Jewish woman more than his own ancestry that initially made him the focus of the 1938 Racial Laws. By 1939 he was being referred to in OVRA files as a "Jewish writer." Claiming to seek exemption from the Racial Laws for his son, in 1938 Pitigrilli sought a ruling on his marriage from the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Vatican City, the city-state ruled by the pope in Rome, including St. Peter's Basilica, Sistine Chapel, Vatican Museum

The Holy See

* The Holy See, the governing body of the Catholic Church and sovereign entity recognized ...

, which held it had never happened, as it took place outside the church. They ruled his first wife was effectively a concubine.

In July 1940 in Genoa, after he had already been interned as a Jew in Uscio, a small town nearby, Pitigrilli married the attorney Lina Furlan of Turin, who had handled his case with the Vatican. A Catholic, she was violating racial purity laws by marrying someone considered to be Jewish. They had a son in mid-1943, Pier Maria Furlan, who was baptized a Catholic.Stille (1991/2003), ''Benevolence and Betrayal'', p. 155

Career

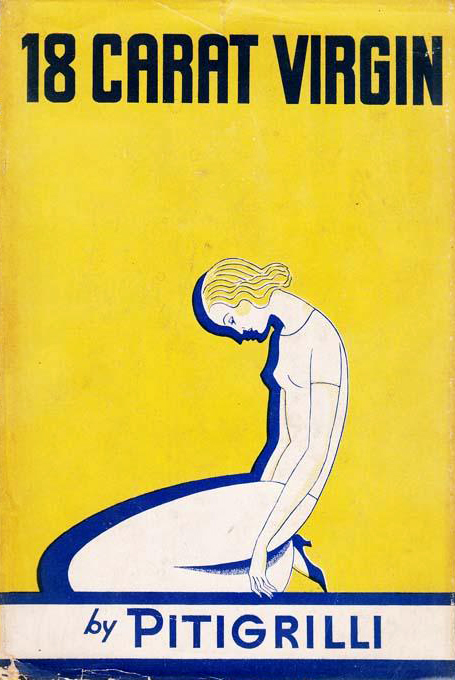

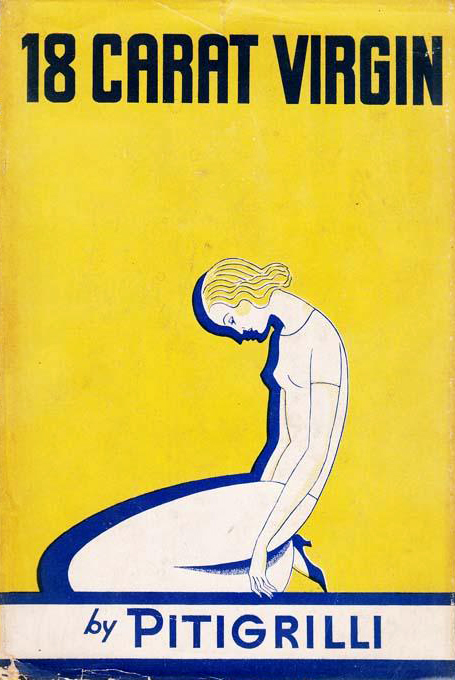

As a young adult, Segre had started working as a journalist and novelist in Turin, a center of literary culture. His early experiences in Paris inspired his most famous novel, ''Cocaine'' (1921), published in Italian under his pseudonym of "Pitigrilli". Due to his portrayal of drug use and sex, the Catholic Church listed it as a " forbidden book." It has been translated into numerous languages, reprinted in new editions, and become a classic. ''Cocaine'' established Pitigrilli as a literary figure in Italy. It was not translated into English until 1933; it was reissued in the 1970s, and a release byNew Vessel Press

New Vessel Press is an independent publishing house specializing in the translation of foreign literature and narrative nonfiction into English.

New Vessel Press books have been widely reviewed in publications including ''The New York Times' ...

is scheduled for September 2013. ''The New York Times'' wrote: “The name of the author Pitigrilli … is so well known in Italy as to be almost a byword for ‘naughtiness’ … The only wonder to us is that some enterprising translator did not render some of his books available in English sooner.”

Alexander Stille, who documented Segre's later collaboration with the fascist government (see below), wrote:

In 1924 Segre founded the literary magazine '' Grandi Firme'', which attracted a large readership of young literati. Rising young writers and illustrators had work featured in the magazine. Redesigned by César Civita

César Civita, born Cesare Civita (September 4, 1905 — April 9, 2005) was an American- Argentine publisher, who in 1936 became general manager of Arnoldo Mondadori Editore in Italy. Following passage of the Race Laws in 1938, he emigrated with ...

, the magazine operated until 1938, when the Fascist government of Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

banned publications owned by Jews under the anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

Race Laws.

Pitigrilli was noted as an aphorist

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by trad ...

. Among his most well-known aphorisms are "Fragments: a providential resource for writers who don't know how to put together an entire book" and "Grammar: a complicated structure that teaches language but impedes speaking."

Fascism and World War II

From 1930 Segre started traveling around Europe, staying mainly in Paris with brief periods in Italy. In 1936 the fascist government prevented reprinting of his books, on moral grounds. Seeking to join the Fascist Party, he wrote directly to Mussolini in 1938. By that time, he was already working as an informant forOVRA

The OVRA, whose most probable name was Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism ( it, Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Repressione dell'Antifascismo), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy, founded in 1927 under the ...

, the secret service of the Fascist government. He provided information about anti-fascist Jewish writers in his circle, as well as Jewish relatives. OVRA dismissed him in 1939, after he was exposed in Paris when a file including his name was found by French police in the flat of Vincenzo Bellavia, the OVRA director there.Stille (1991/2003), ''Benevolence and Betrayal'', pp. 150-152

Despite his work for the government, Pitigrilli began to be persecuted as a Jew. His books were banned, as was his magazine, and he could not write for other magazines. In June 1940, Italy entered the war as an ally of Nazi Germany. Turin police included Pitigrilli on a list of "dangerous Jews" to be interned in the south of Italy in Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

. He and his lawyer, with the help of the intervention of Edvige Mussolini

Edvige Mussolini (; Predappio, 10 November 1888 - Rome, 20 May 1952) was the younger sister of Arnaldo and Benito Mussolini.

Biography

Edvige was the daughter of Alessandro Mussolini, a blacksmith and activist, first anarchist and later socialis ...

, were able to have the place of internment changed to Uscio

Uscio ( lij, Aosci) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Genoa in the Italian region Liguria, located about east of Genoa.

Uscio borders the following municipalities: Avegno, Lumarzo, Neirone, Sori, Tribogna

Tribogna ( ...

, a small town near the Riviera that was two hours from Turin.

Pitigrilli appealed directly to the government for release from internal exile, and was freed by the end of the year. By 1941 he went to Rome, where he wrote movie dialog anonymously to circumvent the racial law and make some kind of living. He offered his services again to OVRA, saying his status as a persecuted Jew would provide him cover. He was seeking to have Aryan status confirmed, as he had been baptized Catholic. He was never rehired, and never gained a change in his racial status.

In July 1943 Mussolini's fascist regime fell. Six weeks later the Germans occupied Italy, and Pitigrilli fled to neutral Switzerland. His wife and daughter, who were recorded as Catholic, could travel openly and joined him there. They lived in Switzerland until 1947 and after the war's end.

Postwar years

In 1948 Segre and his family moved to Argentina, then under the rule ofJuan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine Army general and politician. After serving in several government positions, including Minister of Labour and Vice President of a military dictatorship, he was elected P ...

. They remained there for ten years. He continued to write but had no novels published in Italy from 1938 to 1948.

In 1958, Pitigrilli moved with his family again, returning to Europe to live in Paris. He occasionally visited his house in Turin

Turin ( , Piedmontese language, Piedmontese: ; it, Torino ) is a city and an important business and cultural centre in Northern Italy. It is the capital city of Piedmont and of the Metropolitan City of Turin, and was the first Italian capital ...

, which he had managed to keep. He continued to write and publish novels as Pitigrilli until 1974. He died in Turin in 1975.

Following his death, his ''Dolicocefala Bionda'' and ''L'Esperimento di Pott,'' two early novels, were re-issued in one edition in 1976 with an introduction by the noted Italian author Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian medievalist, philosopher, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular 1980 novel ''The Name of the ...

. Eco wrote: “Pitigrilli was an enjoyable writer – spicy and rapid – like lightning.”

Collaboration with the Fascist regime

In 1991Alexander Stille

Alexander Stille (born 1 January 1957 in New York City) is an American author and journalist. He is the son of Ugo Stille, a well-known Italian journalist and a former editor of Italy's Milan-based Corriere della Sera newspaper. Alexander Stille g ...

published ''Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families under Fascism''. Stille documents how Pitigrilli acted as an informant for the Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

secret police OVRA

The OVRA, whose most probable name was Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism ( it, Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Repressione dell'Antifascismo), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy, founded in 1927 under the ...

during the 1930s, until 1939.Alexander Stille. ''Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families under Fascism''p. 356. Picador, 1991 (reissued by Macmillan, 2003) Stille noted that the Fascist secret police used intelligence from these conversations to arrest and prosecute anti-fascist Jewish friends and relatives of Pitigrilli. Stille used many documents and accounts by members of the clandestine anti-fascist movement Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Freedom) operating in Turin. An Italian post-war government committee investigating collaborators and OVRA concluded about the writer: "…the last doubt (on Pitigrilli being OVRA informant number 373) could not stand after the unequivocal and categorical testimonies … about encounters and confidential conversations that took place exclusively with Pitigrilli."

Works

* ''Mammiferi di Lusso'' (1920) * ''Cocaina'' (1921) * ''The Man Who Searched for Love'' (1929) * ''L'esperimento di Pott'' (1929) * ''Dolicocefala Bionda'' (1936) * ''Le Amanti. La Decadenza del Paradosso'' (1938) * ''La Piscina di Siloe'' (1948) * ''La moglie di Putifarre'' (1953) * ''Amore a Prezzo Fesso'' (short stories, 1963)"Pitigrilli", search for worksHathi Trust Digital Library, University of California, accessed 23 June 2013 * ''La Donna di 30, 40, 50, 60 Anni'' (1967) * ''L'Ombelico di Adamo. Peperoni dolci'' (1970) * ''Sette delitti'' (1971) * ''Nostra Signora di Miss Tif'' (1974)

English translations

* ''The Man Who Searched for Love'', translated by Warre B. Wells. New York: R. M. McBride & Company, 1932. * ''Cocaine'', New York: Greenberg, 1933. Reissued in 1974, AND/OR Press, San Francisco. Reissue in 2013 byNew Vessel Press

New Vessel Press is an independent publishing house specializing in the translation of foreign literature and narrative nonfiction into English.

New Vessel Press books have been widely reviewed in publications including ''The New York Times' ...

, release on 15 September 2013.''Cocaine''New Vessel Press

References

External links

Angiolo Paschetta, ''Il fenomeno Pitigrilli''

, Torino: Casa Editrice Sfinge, 1922, text online at Hathi Trust Digital Library, University of California {{Authority control 1893 births 1975 deaths Writers from Turin Italian male writers University of Turin alumni Italian spies Jewish Italian writers