Diamond Marimba on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harry Partch (June 24, 1901 – September 3, 1974) was an American composer,

Partch was born on June 24, 1901, in

Partch was born on June 24, 1901, in

The family moved to Los Angeles in 1919 following the death of Partch's father. There, his mother was killed in a trolley accident in 1920. He enrolled in the

The family moved to Los Angeles in 1919 following the death of Partch's father. There, his mother was killed in a trolley accident in 1920. He enrolled in the

Partch made public his theories in his book ''

Partch made public his theories in his book ''

File:Harry Partch Institute-6.jpg, alt=A closeup of a keyboard, whose keys are colorfully painted and marked with numbers, Part of the keyboard of the Chromelodeon

File:Harry Partch Institute-8.jpg, Boo II on display at a Harry Partch Institute open house

File:Harry Partch Institute-3.jpg, Quadrangularis Reversum

Corporeal Meadows – The Legacy of Harry Partch: produced for the Harry Parch Estate

Corporeal Meadows Archive – of the earlier incarnation of Corporeal Meadows

* ttps://www.secondinversion.org/2017/05/30/harry-partch-party-celebrating-a-musical-maverick/ Harry Partch: Celebrating a Musical Maverickat Second Inversion

Not even Harry Partch can be an island

at Second Inversion

Art of the States: Harry Partch – Three works by the composer

Enclosures Series: Harry Partch's archives published as book, film and audio from innova

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090501192041/http://www.pas.org/About/HofDetails.cfm?IFile=partch PAS Hall of Fame listing for Harry Partch

Listen to an excerpt from Partch's "Delusion of the Fury" at Acousmata music blog

Finding Aid for Harry Partch Estate Archive, 1918–1991, The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music

Transcript of BBC documentary "The Outsider: The Life and Times of Harry Partch"

Harry Partch

at Music of the United States of America (MUSA) * *

MSS 629

Special Collections & Archives

UC San Diego Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Partch, Harry 1901 births 1974 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American inventors 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century LGBT people 20th-century American musicologists American avant-garde musicians American classical composers American classical violists American gay musicians American male classical composers American multi-instrumentalists American music theorists American musical instrument makers Columbia Records artists Experimental composers Inventors of musical instruments Inventors of musical tunings Just intonation composers LGBT artists from the United States LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians American LGBT musicians LGBT people from California Marimbists Modernist composers Music & Arts artists Music theorists Musicians from Oakland, California Outsider musicians People from Benson, Arizona

music theorist

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. ''The Oxford Companion to Music'' describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the " rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (k ...

, and creator of unique musical instruments

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

. He composed using scales of unequal intervals in just intonation, and was one of the first 20th-century composers in the West to work systematically with microtonal

Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones— intervals smaller than a semitone, also called "microintervals". It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Western tuning of t ...

scales, alongside Lou Harrison

Lou Silver Harrison (May 14, 1917 – February 2, 2003) was an American composer, music critic, music theorist, painter, and creator of unique musical instruments. Harrison initially wrote in a dissonant, ultramodernist style similar to his for ...

. He built custom-made instruments

An experimental musical instrument (or custom-made instrument) is a musical instrument that modifies or extends an existing instrument or class of instruments, or defines or creates a new class of instrument. Some are created through simple modi ...

in these tunings on which to play his compositions, and described the method behind his theory and practice in his book ''Genesis of a Music

''Genesis of a Music'' is a book first published in 1949 by microtonal composer Harry Partch (1901–1974).

Partch first presents a polemic against both equal temperament and the long history of stagnation in the teaching of music; according ...

'' (1947).

Partch composed with scales dividing the octave into 43 unequal tones derived from the natural harmonic series; these scales allowed for more tones of smaller intervals

Interval may refer to:

Mathematics and physics

* Interval (mathematics), a range of numbers

** Partially ordered set#Intervals, its generalization from numbers to arbitrary partially ordered sets

* A statistical level of measurement

* Interval e ...

than in standard Western tuning, which uses twelve equal intervals to the octave. To play his music, Partch built many unique instruments, with such names as the Chromelodeon, the Quadrangularis Reversum, and the Zymo-Xyl. Partch described his music as corporeal, and distinguished it from abstract music

Absolute music (sometimes abstract music) is music that is not explicitly 'about' anything; in contrast to program music, it is non- representational.M. C. Horowitz (ed.), ''New Dictionary of the History of Ideas'', , vol.1, p. 5 The idea of abs ...

, which he perceived as the dominant trend in Western music since the time of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

. His earliest compositions were small-scale pieces to be intoned to instrumental backing; his later works were large-scale, integrated theater productions in which he expected each of the performers to sing, dance, speak, and play instruments. Ancient Greek theatre

Ancient Greek theatre was a theatrical culture that flourished in ancient Greece from 700 BC. The city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political, and religious place during this period, was its centre, where the theatre w ...

and Japanese Noh

is a major form of classical Japanese dance-drama that has been performed since the 14th century. Developed by Kan'ami and his son Zeami, it is the oldest major theatre art that is still regularly performed today. Although the terms Noh and ' ...

and kabuki

is a classical form of Japanese dance- drama. Kabuki theatre is known for its heavily-stylised performances, the often-glamorous costumes worn by performers, and for the elaborate make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki is though ...

heavily influenced his music theatre

Music theatre is a performance genre that emerged over the course of the 20th century, in opposition to more conventional genres like opera and musical theatre. The term came to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s to describe an avant-garde approac ...

.

Encouraged by his mother, Partch learned several instruments at a young age. By fourteen, he was composing, and in particular took to setting dramatic situations. He dropped out of the University of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8.1 ...

's School of Music in 1922 over dissatisfaction with the quality of his teachers. He took to self-study in San Francisco's libraries, where he discovered Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

's ''Sensations of Tone

''On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music'' (German ), commonly referred to as ''Sensations of Tone'', is a foundational work on music acoustics and the perception of sound by Hermann von Helmholtz.

The first ...

'', which convinced him to devote himself to music based on scales tuned in just intonation. In 1930, he burned all his previous compositions in a rejection of the European concert tradition. Partch frequently moved around the US. Early in his career, he was a transient worker, and sometimes a hobo; later he depended on grants, university appointments, and record sales to support himself. In 1970, supporters created the Harry Partch Foundation to administer Partch's music and instruments.

Personal history

Early life (1901–1919)

Partch was born on June 24, 1901, in

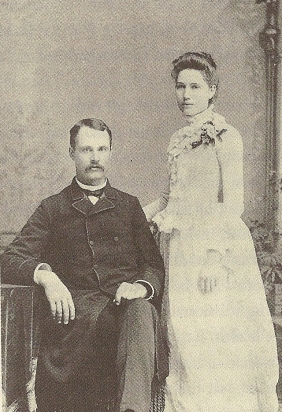

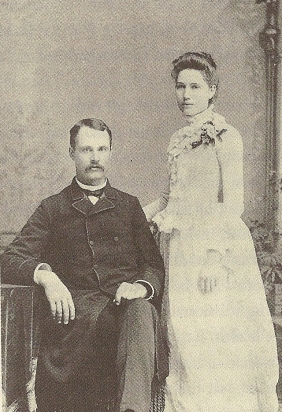

Partch was born on June 24, 1901, in Oakland, California

Oakland is the largest city and the county seat of Alameda County, California, United States. A major West Coast of the United States, West Coast port, Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, the third ...

. His parents were Virgil Franklin Partch (1860–1919) and Jennie ( Childers, 1863–1920). The Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

couple were missionaries, and served in China from 1888 to 1893, and again from 1895 to 1900, when they fled the Boxer Rebellion.

Partch moved with his family to Arizona for his mother's health. His father worked for the Immigration Service there, and they settled in the small town of Benson. It was still the Wild West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

there in the early twentieth century, and Partch recalled seeing outlaws in town. Nearby, there were native Yaqui people

The Yaqui, Hiaki, or Yoeme, are a Native American people of the southwest, who speak a Uto-Aztecan language. Their homelands include the Río Yaqui valley in Sonora, Mexico, and the area below the Gila River in Arizona, Southwestern United St ...

, whose music he heard. His mother sang to him in Mandarin Chinese

Mandarin (; ) is a group of Chinese (Sinitic) dialects that are natively spoken across most of northern and southwestern China. The group includes the Beijing dialect, the basis of the phonology of Standard Chinese, the official language ...

, and he heard and sang songs in Spanish. His mother encouraged her children to learn music, and he learned the mandolin, violin

The violin, sometimes known as a '' fiddle'', is a wooden chordophone ( string instrument) in the violin family. Most violins have a hollow wooden body. It is the smallest and thus highest-pitched instrument ( soprano) in the family in regu ...

, piano

The piano is a stringed keyboard instrument in which the strings are struck by wooden hammers that are coated with a softer material (modern hammers are covered with dense wool felt; some early pianos used leather). It is played using a keybo ...

, reed organ

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. T ...

, and cornet. His mother taught him to read music.

The family moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1913, where Partch seriously studied the piano. He had work playing keyboards for silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized Sound recording and reproduction, recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) ...

s while he was in high school. By 14, he was composing for the piano. He early found an interest in writing music for dramatic situations, and often cited the lost composition ''Death and the Desert'' (1916) as an early example. Partch graduated from high school in 1919.

Early experiments (1919–1947)

The family moved to Los Angeles in 1919 following the death of Partch's father. There, his mother was killed in a trolley accident in 1920. He enrolled in the

The family moved to Los Angeles in 1919 following the death of Partch's father. There, his mother was killed in a trolley accident in 1920. He enrolled in the University of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8.1 ...

's School of Music in 1920, but was dissatisfied with his teachers and left after the summer of 1922. He moved to San Francisco and studied books on music in the libraries there and continued to compose. In 1923 he came to reject the standard twelve-tone equal temperament of Western concert music when he discovered a translation of Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

's ''Sensations of Tone

''On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music'' (German ), commonly referred to as ''Sensations of Tone'', is a foundational work on music acoustics and the perception of sound by Hermann von Helmholtz.

The first ...

''. The book pointed Partch towards just intonation as an acoustic basis for his music. Around this time, while working as an usher for the Los Angeles Philharmonic, he had a romantic relationship with the actor Ramon Novarro

José Ramón Gil Samaniego (February 6, 1899 – October 30, 1968), known professionally as Ramon Novarro, was a Mexican-American actor. He began his career in silent films in 1917 and eventually became a leading man and one of the top box ...

, then known by his birth name Ramón Samaniego; Samaniego broke off the affair when he started to become successful in his acting career.

By 1925, Partch was putting his theory into practice by developing paper coverings for violin and viola with fingerings in just intonation, and wrote a string quartet using such tunings. He put his theories in words in May 1928 in the first draft for a book, then called ''Exposition of Monophony''. He supported himself during this time doing a variety of jobs, including teaching piano, proofreading, and working as a sailor. In New Orleans in 1930, he resolved to break with the European tradition entirely, and burned all his earlier scores in a potbelly stove

A potbelly stove is a cast-iron, coal-burning or wood-burning stove that is cylindrical with a bulge in the middle. Gove PB (editor in chief) (1981). ''Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged''. Springfield ...

.

Partch had a New Orleans violin maker build a viola with the fingerboard of a cello. He used this instrument, dubbed the Adapted Viola, to write music using a scale with twenty-nine tones to the octave. Partch's earliest work to survive comes from this period, including works based on Biblical verse and Shakespeare, and ''Seventeen Lyrics of Li Po'' based on translations of the Chinese poetry of Li Bai

Li Bai (, 701–762), also pronounced as Li Bo, courtesy name Taibai (), was a Chinese poet, acclaimed from his own time to the present as a brilliant and romantic figure who took traditional poetic forms to new heights. He and his friend Du F ...

. In 1932, Partch performed the music in San Francisco and Los Angeles with sopranos he had recruited. A February 9, 1932, performance at Henry Cowell's New Music Society of California attracted reviews. A private group of sponsors sent Partch to New York in 1933, where he gave solo performances and won the support of composers Roy Harris

Roy Ellsworth Harris (February 12, 1898 – October 1, 1979) was an American composer. He wrote music on American subjects, and is best known for his Symphony No. 3.

Life

Harris was born in Chandler, Oklahoma on February 12, 1898. His ancestr ...

, Charles Seeger

Charles Louis Seeger Jr. (December 14, 1886 – February 7, 1979) was an American musicologist, composer, teacher, and folklorist. He was the father of the American folk singers Pete Seeger (1919–2014), Peggy Seeger (b. 1935), and Mike Seeger ( ...

, Henry Cowell, Howard Hanson

Howard Harold Hanson (October 28, 1896 – February 26, 1981)''The New York Times'' – Obituaries. Harold C. Schonberg. February 28, 1981 p. 1011/ref> was an American composer, conductor, educator, music theorist, and champion of American class ...

, Otto Luening

Otto Clarence Luening (June 15, 1900 – September 2, 1996) was a German-American composer and conductor, and an early pioneer of tape music and electronic music.

Luening was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to German parents, Eugene, a conduct ...

, Walter Piston

Walter Hamor Piston, Jr. (January 20, 1894 – November 12, 1976), was an American composer of classical music, music theorist, and professor of music at Harvard University.

Life

Piston was born in Rockland, Maine at 15 Ocean Street to Walter Ha ...

, and Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

.

Partch unsuccessfully applied for Guggenheim grants in 1933 and 1934. The Carnegie Corporation of New York granted him $1500 so he could do research in England. He gave readings at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

and traveled in Europe. He met W. B. Yeats in Dublin, whose translation of Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

' ''King Oedipus

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'' he wanted to set to his music; he studied the spoken inflection in Yeats's recitation of the text. He built a keyboard instrument, the Chromatic Organ, which used a scale with forty-three tones to the octave. He met musicologist Kathleen Schlesinger, who had recreated an ancient Greek kithara from images she found on a vase at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. Partch made sketches of the instrument in her home, and discussed ancient Greek music theory with her.

Partch returned to the U.S. in 1935 at the height of the Great Depression, and spent a transient nine years, often as a hobo, often picking up work or obtaining grants from organizations such as the Federal Writers' Project. For the first eight months of this period, he kept a journal which was published posthumously as ''Bitter Music''. Partch included notation on the speech inflections of people he met in his travels. He continued to compose music, build instruments, and develop his book and theories, and make his first recordings. He had alterations made by sculptor and designer friend Gordon Newell to the Kithara sketches he had made in England. After taking some woodworking courses in 1938, he built his first Kithara at Big Sur, California, at a scale of roughly twice the size of Schlesinger's. In 1942 in Chicago, he built his Chromelodeon—another 43-tone reed organ. He was staying on the eastern coast of the U.S. when he was awarded a Guggenheim grant in March 1943 to construct instruments and complete a seven-part ''Monophonic Cycle''. On April 22, 1944, the first performance of his ''Americana'' series of compositions was given at Carnegie Chamber Music Hall put on by the League of Composers.

University work (1947–1962)

Supported by Guggenheim and university grants, Partch took up residence at theUniversity of Wisconsin

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, ...

from 1944 until 1947. This was a productive period, in which he lectured, trained an ensemble, staged performances, released his first recordings, and completed his book, now called ''Genesis of a Music

''Genesis of a Music'' is a book first published in 1949 by microtonal composer Harry Partch (1901–1974).

Partch first presents a polemic against both equal temperament and the long history of stagnation in the teaching of music; according ...

''. ''Genesis'' was completed in 1947 and published in 1949 by the University of Wisconsin Press

The University of Wisconsin Press (sometimes abbreviated as UW Press) is a non-profit university press publishing peer-reviewed books and journals. It publishes work by scholars from the global academic community; works of fiction, memoir and p ...

. He left the university, as it never accepted him as a member of the permanent staff, and there was little space for his growing stock of instruments.

In 1949, pianist Gunnar Johansen

Gunnar Johansen (January 21, 1906, Copenhagen – May 25, 1991, Blue Mounds, Wisconsin) was a Danish-born pianist and composer. He was one of the chief proponents of the music of Ferruccio Busoni, whose mature keyboard works he recorded in their ...

allowed Partch to convert a smithy on his ranch to a studio. Partch worked there with support from the Guggenheim Foundation, and did recordings, primarily of his ''Eleven Intrusions'' (1949–1950). He was assisted for six months by composer Ben Johnston, who performed on Partch's recordings. In spring 1951, Partch moved to Oakland for health reasons, and prepared for a production of ''King Oedipus'' at Mills College

Mills College at Northeastern University is a private college in Oakland, California and part of Northeastern University's global university system. Mills College was founded as the Young Ladies Seminary in 1852 in Benicia, California; it was ...

, with the support of designer Arch Lauterer. Performances of ''King Oedipus'' in March were extensively reviewed, but a planned recording was blocked by the Yeats estate, which refused to grant permission to use Yeats's translation.

In February 1953, Partch founded the studio Gate 5 in an abandoned shipyard in Sausalito

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located southeast of Marin City, south-southeast of San Rafael, and about north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.

Sausalito's ...

, California, where he composed, built instruments and staged performances. Subscriptions to raise money for recordings were organized by the Harry Partch Trust Fund, an organization put together by friends and supporters. The recordings were sold via mail order, as were later releases on the Gate 5 Records label. The money raised from these recordings became his main source of income. Partch's three ''Plectra and Percussion Dances'', ''Ring Around the Moon'' (1949–1950), ''Castor and Pollux'', and ''Even Wild Horses'', premiered on Berkeley's KPFA radio in November 1953.

After completing ''The Bewitched'' in January 1955, Partch tried to find the means to put on a production of it. Ben Johnston introduced Danlee Mitchell to Partch at the University of Illinois

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (U of I, Illinois, University of Illinois, or UIUC) is a public land-grant research university in Illinois in the twin cities of Champaign and Urbana. It is the flagship institution of the Univer ...

; Mitchell later became Partch's heir. In March 1957, with the help of Johnston and the Fromm Foundation

Paul Fromm (September 28, 1906 – July 4, 1987) was a Jewish Chicago wine merchant and performing arts patron through the Fromm Music Foundation. The ''Organum for Paul Fromm'' was composed by John Harbison in his honor.

Early life

Born in Kitz ...

, ''The Bewitched'' was performed at the University of Illinois, and later at Washington University in St. Louis

Washington University in St. Louis (WashU or WUSTL) is a private research university with its main campus in St. Louis County, and Clayton, Missouri. Founded in 1853, the university is named after George Washington. Washington University is r ...

, though Partch was displeased with choreographer Alwin Nikolais

Alwin Nikolais (November 25, 1910 – May 8, 1993) was an American choreographer, dancer, composer, musician, teacher. He had created the Nikolais Dance Theatre, and was best known for his self-designed innovative costume, lighting and production ...

's interpretation. Later in 1957, Partch provided the music for Madeline Tourtelot's film ''Windsong'', the first of six film collaborations between the two. From 1959 to 1962, Partch received further appointments from the University of Illinois, and staged productions of ''Revelation in the Courthouse Park'' in 1961 and ''Water! Water!'' in 1962. Though these two works were based, as ''King Oedipus'' had been, on Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

, they modernized the settings and incorporated elements of popular music. Partch had support from several departments and organizations at the university, but continuing hostility from the music department convinced him to leave and return to California.

Later life in California (1962–1974)

Partch set up a studio in late 1962 inPetaluma

Petaluma (Miwok: ''Péta Lúuma'') is a city in Sonoma County, California, located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. Its population was 59,776 according to the 2020 census.

Petaluma's name comes from the Miwok village nam ...

, California, in a former chick hatchery. There he composed ''And on the Seventh Day, Petals Fell in Petaluma''. He left in summer 1964, and spent his remaining decade in various cities in southern California. He rarely had university work during this period, and survived on grants, commissions, and record sales. A turning point in his popularity was the 1969 Columbia LP ''The World of Harry Partch'', the first modern recording of Partch's music and its first release on a major record label.

His final theater work was '' Delusion of the Fury'', which incorporated music from ''Petaluma'', and was first produced at the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Franci ...

in early 1969. In 1970, the Harry Partch Foundation was founded to handle the expenses and administration of Partch's work. His final completed work was the soundtrack to Betty Freeman's ''The Dreamer that Remains''. He retired to San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

in 1973, where he died after suffering a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

on September 3, 1974. The same year, a second edition of ''Genesis of a Music'' was published with extra chapters about work and instruments Partch made since the book's original publication.

In 1991, Partch's journals from June 1935 to February 1936 were discovered and published—journals that Partch had believed to have been lost or destroyed. In 1998, musicologist Bob Gilmore

Bob Gilmore (6 June 1961 – 2 January 2015) was a musicologist, educator and keyboard player.

Born in Larne, Northern Ireland, he spent his early years in Carrickfergus. He studied music at York University, England, then at Queen's Univers ...

published a biography of Partch.

Personal life

Partch was first cousins with gag cartoonistVirgil Partch

Virgil Franklin Partch (October 17, 1916 – August 10, 1984), who generally signed his work Vip,Virgil F ...

(1916–1984). Partch was sterile, probably due to childhood mumps, and he had a romantic relationship with the film actor Ramon Novarro

José Ramón Gil Samaniego (February 6, 1899 – October 30, 1968), known professionally as Ramon Novarro, was a Mexican-American actor. He began his career in silent films in 1917 and eventually became a leading man and one of the top box ...

(Ramón Samaniego).

Legacy

Partch met Danlee Mitchell while he was at the University of Illinois; Partch made Mitchell his heir, and Mitchell serves as the Executive Director of the Harry Partch Foundation. Dean Drummond and his group Newband took charge of Partch's instruments, and performed his repertoire. After Drummond's death in 2013, Charles Corey assumed responsibility for the instruments. TheSousa Archives and Center for American Music

The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music (SACAM) documents American music through historical artifacts and archival records in multiple formats. The center is part of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign's library system an ...

in Urbana, Illinois, holds the Harry Partch Estate Archive, 1918–1991, which consists of Partch's personal papers, musical scores, films, tapes and photographs documenting his career as a composer, writer, and producer. It also holds the Music and performing Arts Library Harry Partch Collection, 1914–2007, which consists of books, music, films, personal papers, artifacts and sound recordings collected by the staff of the Music and Performing Arts Library and the University of Illinois School of Music documenting the life and career of Harry Partch, and those associated with him, throughout his career as a composer and writer.

Partch's notation is an obstacle, as it mixes a sort of tablature

Tablature (or tabulature, or tab for short) is a form of musical notation indicating instrument fingering rather than musical pitches.

Tablature is common for fretted stringed instruments such as the guitar, lute or vihuela, as well as many fr ...

with indications of pitch ratios. This makes it difficult for those trained in traditional Western notation, and gives no visual indication as to what the music is intended to sound like.

Paul Simon used Partch's instruments in the creation of songs for the album ''Stranger to Stranger

''Stranger to Stranger'' is the thirteenth solo studio album by American folk rock singer-songwriter Paul Simon. Produced by Paul Simon and Roy Halee, it was released on June 3, 2016 through Concord Records. Simon wrote the material over a period ...

''.

Recognition

In 1974, Partch was inducted into the Hall of Fame of the Percussive Arts Society, a music service organization promoting percussion education, research, performance and appreciation throughout the world. In 2004, ''U.S. Highball'' was selected by theLibrary of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

's National Recording Preservation Board

The United States National Recording Preservation Board selects recorded sounds for preservation in the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry. The National Recording Registry was initiated to maintain and preserve "sound recordings that ...

as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Music

Theory

Genesis of a Music

''Genesis of a Music'' is a book first published in 1949 by microtonal composer Harry Partch (1901–1974).

Partch first presents a polemic against both equal temperament and the long history of stagnation in the teaching of music; according ...

'' (1947). He opens the book with an overview of music history, and argues that Western music began to suffer from the time of Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the ''Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wor ...

, after which twelve-tone equal temperament was adopted to the exclusion of other tuning systems, and abstract, instrumental music became the norm. Partch sought to bring vocal music back to prominence, and adopted tunings and scales he believed more suitable to singing.

Inspired by ''Sensations of Tone

''On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music'' (German ), commonly referred to as ''Sensations of Tone'', is a foundational work on music acoustics and the perception of sound by Hermann von Helmholtz.

The first ...

'', Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Associatio ...

's book on acoustics and the perception of sound, Partch based his music strictly on just intonation. He tuned his instruments using the overtone series

A harmonic series (also overtone series) is the sequence of harmonics, musical tones, or pure tones whose frequency is an integer multiple of a ''fundamental frequency''.

Pitched musical instruments are often based on an acoustic resonator suc ...

, and extended it up to the eleventh partial. This allowed for a larger number of smaller, unequal intervals than found in the Western classical music tradition's twelve-tone equal temperament. Partch's tuning is often classed as microtonality

Microtonal music or microtonality is the use in music of microtones—interval (music), intervals smaller than a semitone, also called "microintervals". It may also be extended to include any music using intervals not found in the customary Wes ...

, as it allowed for intervals smaller than 100 cents, though Partch did not conceive his tuning in such a context. Instead, he saw it as a return to pre-Classical Western musical roots, in particular to the music of the ancient Greeks. By taking the principles he found in Helmholtz's book, he expanded his tuning system until it allowed for a division of the octave into 43 tones based on ratios of small integers.

Partch uses the terms Otonality and Utonality

''Otonality'' and ''utonality'' are terms introduced by Harry Partch to describe chords whose pitch classes are the harmonics or subharmonics of a given fixed tone ( identity), respectively. For example: , , ,... or , , ,....

Definitio ...

to describe chords whose pitch class

In music, a pitch class (p.c. or pc) is a set of all pitches that are a whole number of octaves apart; for example, the pitch class C consists of the Cs in all octaves. "The pitch class C stands for all possible Cs, in whatever octave positio ...

es are the harmonics or subharmonics of a given fixed tone. These six-tone chords function in Partch's music much the same that the three-tone major and minor chords (or triads) do in classical music. The Otonalities are derived from the overtone series

A harmonic series (also overtone series) is the sequence of harmonics, musical tones, or pure tones whose frequency is an integer multiple of a ''fundamental frequency''.

Pitched musical instruments are often based on an acoustic resonator suc ...

, and the Utonalities from the undertone series

In music, the undertone series or subharmonic series is a sequence of notes that results from inverting the intervals of the overtone series. While overtones naturally occur with the physical production of music on instruments, undertones must ...

.

Style

Partch rejected the Western concert music tradition, saying that the music of composers such as Beethoven "has only the feeblest roots" in Western culture. His Orientalism was particularly pronounced—sometimes explicitly, as when he set to music the poetry ofLi Bai

Li Bai (, 701–762), also pronounced as Li Bo, courtesy name Taibai (), was a Chinese poet, acclaimed from his own time to the present as a brilliant and romantic figure who took traditional poetic forms to new heights. He and his friend Du F ...

, or when he combined two Noh dramas with one from Ethiopia in ''The Delusion of the Fury''.

Partch believed that Western music of the 20th century suffered from excessive specialization. He objected to the theatre of the day which he believed had divorced music and drama, and strove to create complete, integrated theatre works in which he expected each performer to sing, dance, play instruments, and take on speaking parts. Partch used the words "ritual" and "corporeal" to describe his theatre works—musicians and their instruments were not hidden in an orchestra pit

An orchestra pit is the area in a theater (usually located in a lowered area in front of the stage) in which musicians perform. Orchestral pits are utilized in forms of theatre that require music (such as opera and ballet) or in cases when incide ...

or offstage, but were a visual part of the performance.

Rhythmic range

Partch's approach to rhythm ranged from unspecified to complex. In ''Seventeen Lyrics of Li Po'' for the Adapted Viola, Partch "doesn't bother with rhythmic notation at all, but simply directs performers to follow the natural rhythms of the poem." His rhythmic structures that were specified in ''Castor and Pollux'' were far more structured: "Each of the duets last 234 beats. In the first half (Castor) the music alternates between 4 and 5 beats to a bar, and there’s usually a rest on the eighth of the nine beats. In the second half (Pollux) the rhythm’s a bit more complicated, with six bars of 7 beats alternating with six bars of 9 beats until 234 beats are reached."Instruments

Partch called himself "a philosophic music-man seduced into carpentry". The path towards Partch's use of various unique instruments was gradual. Partch began in the 1920s using traditional instruments, and wrote a string quartet in just intonation (now lost). He had his first specialized instrument built for him in 1930—the Adapted Viola, a viola with a cello's neck fitted on it. Most of Partch's works used the instruments he created exclusively. Some works made use of unaltered standard instruments such as clarinet orcello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a bowed (sometimes plucked and occasionally hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifths: from low to high, C2, G ...

; ''Revelation in the Courtyard Park'' (1960) used an unaltered small wind band, and ''Yankee Doodle Fantasy'' (1944) used unaltered oboe

The oboe ( ) is a type of double reed woodwind instrument. Oboes are usually made of wood, but may also be made of synthetic materials, such as plastic, resin, or hybrid composites. The most common oboe plays in the treble or soprano range.

...

and flute.

In 1991, Dean Drummond became the custodian of the original Harry Partch instrument collection until his death in 2013. In 1999 Drummond brought the instruments to Montclair State University

Montclair State University (MSU) is a public research university in Montclair, New Jersey, with parts of the campus extending into Little Falls. As of fall 2018, Montclair State was, by enrollment, the second largest public university in New ...

in Montclair, New Jersey

Montclair () is a township in Essex County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. Situated on the cliffs of the Watchung Mountains, Montclair is a wealthy and diverse commuter town and suburb of New York City within the New York metropolitan area. ...

where they resided until November 2014 when they moved to University of Washington in Seattle. They are currently under the care of Charles Corey.

Works

Partch's later works were large-scale, integrated theater productions in which he expected each of the performers to sing, dance, speak, and play instruments. Partch described the theory and practice of his music in his book ''Genesis of a Music'', which he had published first in 1947, and in an expanded edition in 1974. A collection of essays, journals, and librettos by Partch was published as posthumously as ''Bitter Music'' 1991. Partch partially supported himself with the sales of recordings, which he began making in the late 1930s. He published his recordings under the Gate 5 Records label beginning in 1953. On recordings such as the soundtrack to ''Windsong'', he used multitrack recording, which allowed him to play all the instruments himself. He never used synthesized or computer-generated sounds, though he had access to such technology. Partch scored six films by Madeline Tourtelot, starting with 1957's ''Windsong'', and was the subject of a number of documentaries.References

Explanatory notes

Citations

General bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * ''Musical Outsiders: An American Legacy: Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, and Terry Riley''. Directed by Michael Blackwood. (1995) * Zimmerman, Walter, ''Desert Plants – Conversations with 23 American Musicians'', Berlin: Beginner Press in cooperation with Mode Records, 2020 (originally published in 1976 by A.R.C., Vancouver). The 2020 edition includes a cd featuring the original interview recordings with Larry Austin,Robert Ashley

Robert Reynolds Ashley (March 28, 1930 – March 3, 2014) was an American composer, who was best known for his television operas and other theatrical works, many of which incorporate electronics and extended techniques. His works often involve i ...

, Jim Burton, John Cage, Philip Corner, Morton Feldman

Morton Feldman (January 12, 1926 – September 3, 1987) was an American composer. A major figure in 20th-century classical music, Feldman was a pioneer of indeterminate music, a development associated with the experimental New York School ...

, Philip Glass, Joan La Barbara

Joan Linda La Barbara (born June 8, 1947) is an American vocalist and composer known for her explorations of non-conventional or "extended" vocal techniques. Considered to be a vocal virtuoso in the field of contemporary music, she is credited w ...

, Garrett List

Garrett List (September 10, 1943 – December 27, 2019) was an American trombonist, vocalist, and composer.

List was born in Phoenix, Arizona. He studied at California State University, Long Beach, and the Juilliard School. He was a member of Ital ...

, Alvin Lucier, John McGuire, Charles Morrow, J.B. Floyd (on Conlon Nancarrow

Samuel Conlon Nancarrow (; October 27, 1912 – August 10, 1997) was an American- Mexican composer who lived and worked in Mexico for most of his life. Nancarrow is best remembered for his ''Studies for Player Piano'', being one of the firs ...

), Pauline Oliveros

Pauline Oliveros (May 30, 1932 – November 24, 2016) was an American composer, accordionist and a central figure in the development of post-war experimental and electronic music.

She was a founding member of the San Francisco Tape Music Cente ...

, Charlemagne Palestine

Chaim Moshe Tzadik Palestine (born 1947), known professionally as Charlemagne Palestine, is an American visual artist and musician. He has been described as being one of the founders of New York school of minimalist music, first initiated by La M ...

, Ben Johnston (on Harry Partch), Steve Reich, David Rosenboom

David Rosenboom (born 1947 in Fairfield, Iowa) is a composer-performer, interdisciplinary artist, author, and educator known for his work in American experimental music.

Rosenboom has explored various forms of music, languages for improvisation, ...

, Frederic Rzewski

Frederic Anthony Rzewski ( ; April 13, 1938 – June 26, 2021) was an American composer and pianist, considered to be one of the most important American composer-pianists of his time. His major compositions, which often incorporate social an ...

, Richard Teitelbaum

Richard Lowe Teitelbaum (May 19, 1939 – April 9, 2020) was an American composer, keyboardist, and improvisor. A student of Allen Forte, Mel Powell, and Luigi Nono, he was known for his live electronic music and synthesizer performances. He was ...

, James Tenney

James Tenney (August 10, 1934 – August 24, 2006) was an American composer and music theorist. He made significant early musical contributions to plunderphonics, sound synthesis, algorithmic composition, process music, spectral music, microto ...

, Christian Wolff, and La Monte Young.

External links

Corporeal Meadows – The Legacy of Harry Partch: produced for the Harry Parch Estate

Corporeal Meadows Archive – of the earlier incarnation of Corporeal Meadows

* ttps://www.secondinversion.org/2017/05/30/harry-partch-party-celebrating-a-musical-maverick/ Harry Partch: Celebrating a Musical Maverickat Second Inversion

Not even Harry Partch can be an island

at Second Inversion

Art of the States: Harry Partch – Three works by the composer

Enclosures Series: Harry Partch's archives published as book, film and audio from innova

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090501192041/http://www.pas.org/About/HofDetails.cfm?IFile=partch PAS Hall of Fame listing for Harry Partch

Listen to an excerpt from Partch's "Delusion of the Fury" at Acousmata music blog

Finding Aid for Harry Partch Estate Archive, 1918–1991, The Sousa Archives and Center for American Music

Transcript of BBC documentary "The Outsider: The Life and Times of Harry Partch"

Harry Partch

at Music of the United States of America (MUSA) * *

MSS 629

Special Collections & Archives

UC San Diego Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Partch, Harry 1901 births 1974 deaths 20th-century American composers 20th-century American inventors 20th-century American male musicians 20th-century American musicians 20th-century classical composers 20th-century LGBT people 20th-century American musicologists American avant-garde musicians American classical composers American classical violists American gay musicians American male classical composers American multi-instrumentalists American music theorists American musical instrument makers Columbia Records artists Experimental composers Inventors of musical instruments Inventors of musical tunings Just intonation composers LGBT artists from the United States LGBT classical composers LGBT classical musicians American LGBT musicians LGBT people from California Marimbists Modernist composers Music & Arts artists Music theorists Musicians from Oakland, California Outsider musicians People from Benson, Arizona