Depression Of 1873–79 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Long Depression was a worldwide price and economic

In 1873, during a decline in the value of silver—exacerbated by the end of the German Empire's production of ''

In 1873, during a decline in the value of silver—exacerbated by the end of the German Empire's production of ''

In the United States, the Long Depression began with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. Figures from

In the United States, the Long Depression began with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. Figures from

online edition

2:811 Recovery began in 1878. The mileage of railroad track laid down increased from in 1878 to 11,568 in 1882. Construction began recovery by 1879; the value of building permits increased two and a half times between 1878 and 1883, and unemployment fell to 2.5% in spite of (or perhaps facilitated by) high immigration. The recovery, however, proved short-lived. Business profits declined steeply between 1882 and 1884. The recovery in railroad construction reversed itself, falling from of track laid in 1882 to of track laid in 1885; the price of steel rails collapsed from $71/ton in 1880 to $20/ton in 1884. Manufacturing again collapsed - durable goods output fell by a quarter again. The decline became another financial crisis in 1884, when multiple New York banks collapsed; simultaneously, in 1883–1884, tens of millions of dollars of foreign-owned American securities were sold out of fears that the United States was preparing to abandon the gold standard. This financial panic destroyed eleven New York banks, more than a hundred state banks, and led to defaults on at least $32 million worth of debt. Unemployment, which had stood at 2.5% between recessions, surged to 7.5% in 1884–1885, and 13% in the northeastern United States, even as immigration plunged in response to deteriorating labor markets. This second recession led to further deterioration of farm prices.

"A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II"

(pdf), The War of 1812 and its Aftermath, p.145, 153-156. As economist

"Less Than Zero - The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy"

''The Institute of Economic Affairs'', 1997, p.49-53. Referenced 2011-01-15.

In JSTOR

{{Reconstruction Era 1873 establishments 1896 disestablishments Economic collapses Recessions Late modern Europe 19th-century economic history 1870s economic history 1880s economic history 1890s economic history 1873 in economics

recession

In economics, a recession is a business cycle contraction when there is a general decline in economic activity. Recessions generally occur when there is a widespread drop in spending (an adverse demand shock). This may be triggered by various ...

, beginning in 1873 and running either through March 1879, or 1896, depending on the metrics used. It was most severe in Europe and the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fueled by the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Firs ...

in the decade following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. The episode was labeled the "Great Depression" at the time, and it held that designation until the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s. Though a period of general deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflation ...

and a general contraction, it did not have the severe economic retrogression of the Great Depression.

It was most notable in Western Europe and North America, at least in part because reliable data from the period is most readily available in those parts of the world. The United Kingdom is often considered to have been the hardest hit; during this period it lost some of its large industrial lead over the economies of continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

. While it was occurring, the view was prominent that the economy of the United Kingdom had been in continuous depression from 1873 to as late as 1896 and some texts refer to the period as the Great Depression of 1873–1896, with financial and manufacturing losses reinforced by a long recession in the UK agricultural sector.

In the United States, economists typically refer to the Long Depression as the Depression of 1873–1879, kicked off by the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

, and followed by the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

, book-ending the entire period of the wider Long Depression. The U.S. National Bureau of Economic Research

The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is an American private nonprofit research organization "committed to undertaking and disseminating unbiased economic research among public policymakers, business professionals, and the academic c ...

dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. In the United States, from 1873 to 1879, 18,000 businesses went bankrupt, including 89 railroads. Ten states and hundreds of banks went bankrupt. Unemployment peaked in 1878, long after the initial financial panic of 1873 had ended. Different sources peg the peak U.S. unemployment rate anywhere from 8.25% to 14%.

Background

The period preceding the depression was dominated by several major military conflicts and a period of economic expansion. In Europe, the end of the Franco-Prussian War yielded a new political order inGermany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and the £200 million indemnity imposed on France led to an inflationary investment boom in Germany and Central Europe. New technologies in industry such as the Bessemer converter

The Bessemer process was the first inexpensive industrial process for the mass production of steel from molten pig iron before the development of the open hearth furnace. The key principle is removal of impurities from the iron by oxidation with ...

were being rapidly applied; railroads were booming. In the United States, the end of the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

and a brief post-war recession (1865–1867) gave way to an investment boom, focused especially on railroads on public lands in the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

- an expansion funded greatly by foreign investors.

Causes of the crisis

In 1873, during a decline in the value of silver—exacerbated by the end of the German Empire's production of ''

In 1873, during a decline in the value of silver—exacerbated by the end of the German Empire's production of ''thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter of ...

'' coins—the US government passed the Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

in April. This essentially ended the bimetallic standard

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

of the United States, forcing it for the first time onto a pure gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

. This measure, referred to by its opponents as "the Crime of 1873" and the topic of William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

's Cross of Gold speech

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported "free silver" (i.e. bimetal ...

in 1896, forced a contraction of the money supply

In macroeconomics, the money supply (or money stock) refers to the total volume of currency held by the public at a particular point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures usually include Circulation (curren ...

in the United States. It also drove down silver prices further, even as new silver mines were being established in Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

, which stimulated mining investment but increased supply as demand was falling. Silver miners arrived at US mints, unaware of the ban on production of silver coins, only to find their product no longer welcome. By September, the US economy was in a crisis, deflation causing banking panics and destabilizing business investment, climaxing in the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

.

The Panic of 1873 has been described as "the first truly international crisis". The optimism that had been driving booming stock prices in central Europe had reached a fever pitch, and fears of a bubble culminated in a panic in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

beginning in April 1873. The collapse of the Vienna Stock Exchange

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

began on May 8, 1873, and continued until May 10, when the exchange was closed; when it was reopened three days later, the panic seemed to have faded, and appeared confined to Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

. Financial panic arrived in the Americas only months later on Black Thursday

Black Thursday is a term used to refer to typically negative, notable events that have occurred on a Thursday. It has been used in the following cases:

*6 February 1851, bushfires in Victoria, Australia.

*18 September 1873, during the Panic of ...

, September 18, 1873, after the failure of the banking house of Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke (August 10, 1821 – February 16, 1905) was an American financier who helped finance the Union war effort during the American Civil War and the postwar development of railroads in the northwestern United States. He is generally acknowle ...

and Company over the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whic ...

. The Northern Pacific railway had been given of public land in the Western United States and Cooke sought $100,000,000 in capital for the company; the bank failed when the bond issue proved unsalable, and was shortly followed by several other major banks. The New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE, nicknamed "The Big Board") is an American stock exchange in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It is by far the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed c ...

closed for ten days on September 20.

The financial contagion

Financial contagion refers to "the spread of market disturbances mostly on the downside from one country to the other, a process observed through co-movements in exchange rates, stock prices, sovereign spreads, and capital flows". Financial contag ...

then returned to Europe, provoking a second panic in Vienna and further failures in continental Europe before receding. France, which had been experiencing deflation in the years preceding the crash, was spared financial calamity for the moment, as was Britain.

Some have argued the depression was rooted in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War that devastated the French economy and, under the Treaty of Frankfurt The Treaty of Frankfurt may refer to one of three treaties signed at Frankfurt, as follows:

* Treaty of Frankfurt (1489) - Treaty between Maximilian of Austria and the envoys of King Charles VIII of France

*Treaty of Frankfurt (1539) - Initiated ...

, forced that country to make large war reparations

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover damage or injury inflicted during a war.

History

Making one party pay a war indemnity is a common practice with a long history.

R ...

payments to Germany. The primary cause of the price depression in the United States was the tight monetary policy that the United States followed to get back to the gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

after the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The U.S. government was taking money out of circulation to achieve this goal, therefore there was less available money to facilitate trade. Because of this monetary policy the price of silver

A price is the (usually not negative) quantity of payment or compensation given by one party to another in return for goods or services. In some situations, the price of production has a different name. If the product is a "good" in the c ...

started to fall causing considerable losses of asset values; by most accounts, after 1879 production was growing, thus further putting downward pressure on prices due to increased industrial productivity, trade and competition.

In the US the speculative nature of financing due to both the greenback, which was paper currency issued to pay for the Civil War and rampant fraud in the building of the Union Pacific Railway

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

up to 1869 culminated in the Crédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the First transcontinental railroad. ...

. Railway overbuilding and weak markets collapsed the bubble in 1873. Both the Union Pacific and the Northern Pacific lines were central to the collapse; another railway bubble was the Railway Mania

Railway Mania was an instance of a stock market bubble in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in the 1840s. It followed a common pattern: as the price of railway shares increased, speculators invested more money, which further incre ...

in the United Kingdom.

Because of the Panic of 1873, governments depegged their currencies, to save money. The demonetization of silver by European and North American governments in the early 1870s was certainly a contributing factor. The US Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

was met with great opposition by farmers and miners, as silver was seen as more of a monetary benefit to rural areas than to banks in big cities. In addition, there were US citizens who advocated the continuance of government-issued fiat money

Fiat money (from la, fiat, "let it be done") is a type of currency that is not backed by any commodity such as gold or silver. It is typically designated by the issuing government to be legal tender. Throughout history, fiat money was sometime ...

(United States Note

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, is a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for 109 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were k ...

s) to avoid deflation and promote exports. The western US states were outraged—Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, Western region of the United States. It is bordered by Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. N ...

, Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

, and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

were huge silver producers with productive mines, and for a few years mining abated. Resumption of silver dollar coinage was authorized by the Bland–Allison Act

The Bland–Allison Act, also referred to as the Grand Bland Plan of 1878, was an act of United States Congress requiring the U.S. Treasury to buy a certain amount of silver and put it into circulation as silver dollars. Though the bill was vetoe ...

of 1878. The resumption of the US government buying silver was enacted in 1890 with the Sherman Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

.

Monetarist

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national ...

s believe that the 1873 depression was caused by shortages of gold that undermined the gold standard, and that the 1848 California Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

, 1886 Witwatersrand Gold Rush

The Witwatersrand Gold Rush was a gold rush in 1886 that led to the establishment of Johannesburg, South Africa. It was a part of the Mineral Revolution.

Origins

In the modern day province of Mpumalanga, gold miners in the alluvial mines of B ...

in South Africa and the 1896–99 Klondike Gold Rush helped alleviate such crises. Other analyses have pointed to developmental surges (see Kondratiev wave

In economics, Kondratiev waves (also called supercycles, great surges, long waves, K-waves or the long economic cycle) are hypothesized cycle-like phenomena in the modern world economy. The phenomenon is closely connected with the technology li ...

), theorizing that the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Firs ...

was causing large shifts in the economies of many states, imposing transition costs, which may also have played a role in causing the depression.

Course of the depression

Like the laterGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, the Long Depression affected different countries at different times, at different rates, and some countries accomplished rapid growth over certain periods. Globally, however, the 1870s, 1880s, and 1890s were a period of falling price levels and rates of economic growth significantly below the periods preceding and following.

Between 1870 and 1890, iron production in the five largest producing countries more than doubled, from 11 million tons to 23 million tons, steel production increased twentyfold (half a million tons to 11 million tons), and railroad

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

development boomed. But at the same time, prices in several markets collapsed - the price of grain

A grain is a small, hard, dry fruit (caryopsis) – with or without an attached hull layer – harvested for human or animal consumption. A grain crop is a grain-producing plant. The two main types of commercial grain crops are cereals and legum ...

in 1894 was only a third what it had been in 1867, and the price of cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

fell by nearly 50 percent in just the five years from 1872 to 1877, imposing great hardship on farmers and planters. This collapse provoked protectionism in many countries, such as France, Germany, and the United States, while triggering mass emigration from other countries such as Italy, Spain, Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, and Russia. Similarly, while the ''production'' of iron doubled between the 1870s and 1890s, the ''price'' of iron halved.

Many countries experienced significantly lower growth rates relative to what they had experienced earlier in the 19th century and to what they experienced afterwards:

Austria-Hungary

The global economic crisis first erupted inAustria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, where in May 1873 the Vienna Stock Exchange

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

crashed. In Hungary, the panic of 1873 terminated a mania of railroad-building.

Chile

In the late 1870s the economic situation in Chile deteriorated. Chilean wheat exports were outcompeted by production in Canada, Russia andArgentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

and Chilean copper was largely replaced in international markets by copper from the United States and Spain.''Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores.'' 2002. Gabriel Salazar

Gabriel Salazar Vergara (born 31 January 1936) is a Chilean historian. He is known in his country for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements, particularly the recent student protests of 2006 and 2011–12.

Salazar ...

and Julio Pinto

Julio Pinto Vallejos (born 1956) is a Chilean historian. He is known in Chile for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements. In 2016 he won the Chilean National History Award. He is a member of the editorial board of LOM ...

. p. 25-29. Income from silver mining in Chile also dropped. Aníbal Pinto

Aníbal Pinto Garmendia (; March 15, 1825June 9, 1884) was a Chilean political figure. He served as the president of Chile between 1876 and 1881.

Early life

He was born in Santiago de Chile, the son of former Chilean president General Francisco ...

, president of Chile in 1878, expressed his concerns the following way:

This "mining discovery" came, according to historians Gabriel Salazar

Gabriel Salazar Vergara (born 31 January 1936) is a Chilean historian. He is known in his country for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements, particularly the recent student protests of 2006 and 2011–12.

Salazar ...

and Julio Pinto

Julio Pinto Vallejos (born 1956) is a Chilean historian. He is known in Chile for his study of social history and interpretations of social movements. In 2016 he won the Chilean National History Award. He is a member of the editorial board of LOM ...

, into existence through the conquest of Bolivian and Peruvian lands in the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

. It has been argued that economic situation and the view of new wealth in the nitrate was the true reason for the Chilean elite to go into war with its neighbors.

Another response to the economic crisis, according to Jorge Pinto Rodríguez

Jorge Manuel Pinto Rodríguez, ( La Serena 18 December 1944) is a Chilean historian. He is known in Chile for his study of the history of Araucanía, social history and demography

Demography () is the statistical study of populations ...

, was the new pulse of conquest of indigenous lands that took place in Araucanía in the 1880s.Salazar & Pinto 2002, pp. 25-29.

France

France's experience was somewhat unusual. Having been defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, the country was required to pay £200 million inreparations

Reparation(s) may refer to:

Christianity

* Restitution (theology), the Christian doctrine calling for reparation

* Acts of reparation, prayers for repairing the damages of sin

History

*War reparations

**World War I reparations, made from G ...

to the Germans and was already reeling when the 1873 crash occurred. The French adopted a policy of deliberate deflation while paying off the reparations.

While the United States resumed growth for a time in the 1880s, the Paris Bourse crash of 1882

The Paris Bourse crash of 1882 was a stock market crash in France, and was the worst crisis in the French economy in the nineteenth century. The crash was triggered by the collapse of l'Union Générale in January. Around a quarter of the brokers ...

sent France careening into depression, one which "lasted longer and probably cost France more than any other in the 19th century". The Union Générale, a French bank, failed in 1882, prompting the French to withdraw three million pounds from the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

and triggering a collapse in French stock prices.

The financial crisis was compounded by diseases impacting the wine and silk industries French capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form o ...

and foreign investment plummeted to the lowest levels experienced by France in the latter half of the 19th century. After a boom in new investment bank

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing is ...

s after the end of the Franco-Prussian War, the destruction of the French banking industry wrought by the crash cast a pall over the financial sector that lasted until the dawn of the 20th century. French finances were further sunk by failing investments abroad, principally in railroads and buildings. The French net national product Net national product (NNP) refers to gross national product (GNP), i.e. the total market value of all final goods and services produced by the factors of production of a country or other polity during a given time period, minus depreciation. Similar ...

declined over the ten years from 1882 to 1892.

Italy

A ten-yeartariff war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism in which states raise or create tariffs or other trade barriers against each other in response to trade barriers created by the other party. If tariffs are the exclus ...

broke out between France and Italy after 1887, damaging Franco-Italian relations which had prospered during Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

. As France was Italy's biggest investor, the liquidation of French assets in the country was especially damaging.

Russia

The Russian experience was similar to the US experience - three separate recessions, concentrated in manufacturing, occurred in the period (1874–1877, 1881–1886, and 1891–1892), separated by periods of recovery.United Kingdom

The United Kingdom, which had previously experienced crises every decade since the 1820s, was initially less affected by this financial crisis, even though theBank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

kept interest rates as high as 9 percent in the 1870s.

The 1878 failure of the City of Glasgow Bank

The City of Glasgow Bank was a bank in Scotland that was largely known for its spectacular collapse in October 1878, which ruined all but 254 of its 1,200 shareholders since their liability was unlimited.

History

The bank was founded in 1839 wi ...

in Scotland arose through a combination of fraud and speculative investments in Australian and New Zealand companies (agriculture and mining) and in American railroads.

Building on an 1870 reform, and the 1879 famine, thousands of Irish tenant farmer

A tenant farmer is a person (farmer or farmworker) who resides on land owned by a landlord. Tenant farming is an agricultural production system in which landowners contribute their land and often a measure of operating capital and management, ...

s affected by depressed producer prices and high rents launched the Land War

The Land War ( ga, Cogadh na Talún) was a period of agrarian agitation in rural Ireland (then wholly part of the United Kingdom) that began in 1879. It may refer specifically to the first and most intense period of agitation between 1879 and 18 ...

in 1879, which resulted in the reforming Irish Land Acts

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

.

United States

In the United States, the Long Depression began with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. Figures from

In the United States, the Long Depression began with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. Figures from Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and Anna Schwartz

Anna Jacobson Schwartz (pronounced ; November 11, 1915 – June 21, 2012) was an American economist who worked at the National Bureau of Economic Research in New York City and a writer for ''The New York Times''. Paul Krugman has said that Schwar ...

show net national product Net national product (NNP) refers to gross national product (GNP), i.e. the total market value of all final goods and services produced by the factors of production of a country or other polity during a given time period, minus depreciation. Similar ...

increased 3 percent per year from 1869 to 1879 and real national product grew at 6.8 percent per year during that time frame. However, since between 1869 and 1879 the population of the United States increased by over 17.5 percent, per capita NNP growth was lower. Following the end of the episode in 1879, the U.S. economy would remain unstable, experiencing recessions for 114 of the 253 months until January 1901.

The dramatic shift in prices mauled nominal wages - in the United States, nominal wages declined by one-quarter during the 1870s, and as much as one-half in some places, such as Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Although real wages had enjoyed robust growth in the aftermath of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, increasing by nearly a quarter between 1865 and 1873, they stagnated until the 1880s, posting no real growth, before resuming their robust rate of expansion in the later 1880s. The collapse of cotton prices devastated the already war-ravaged economy of the southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Although farm prices fell dramatically, American agriculture continued to expand production.

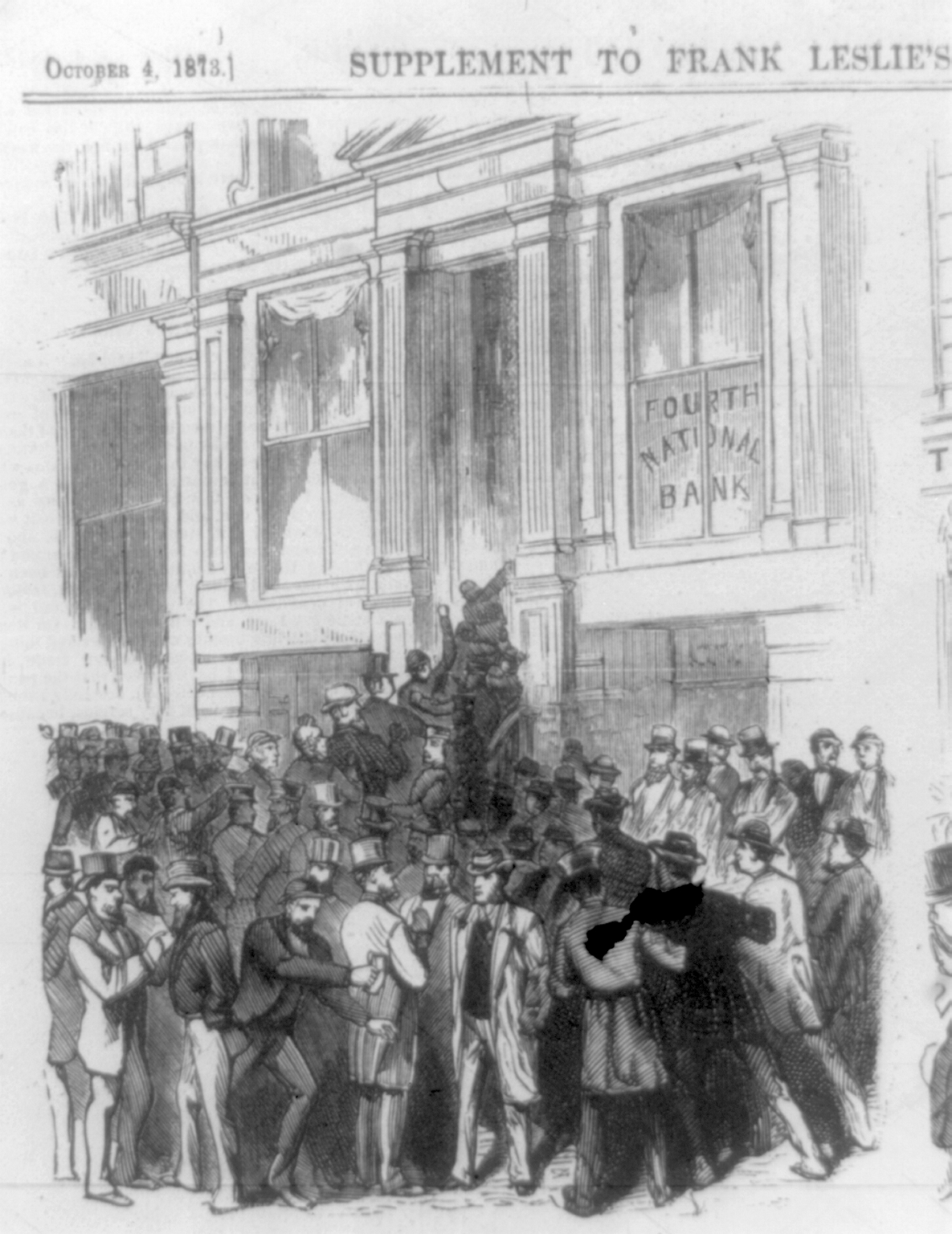

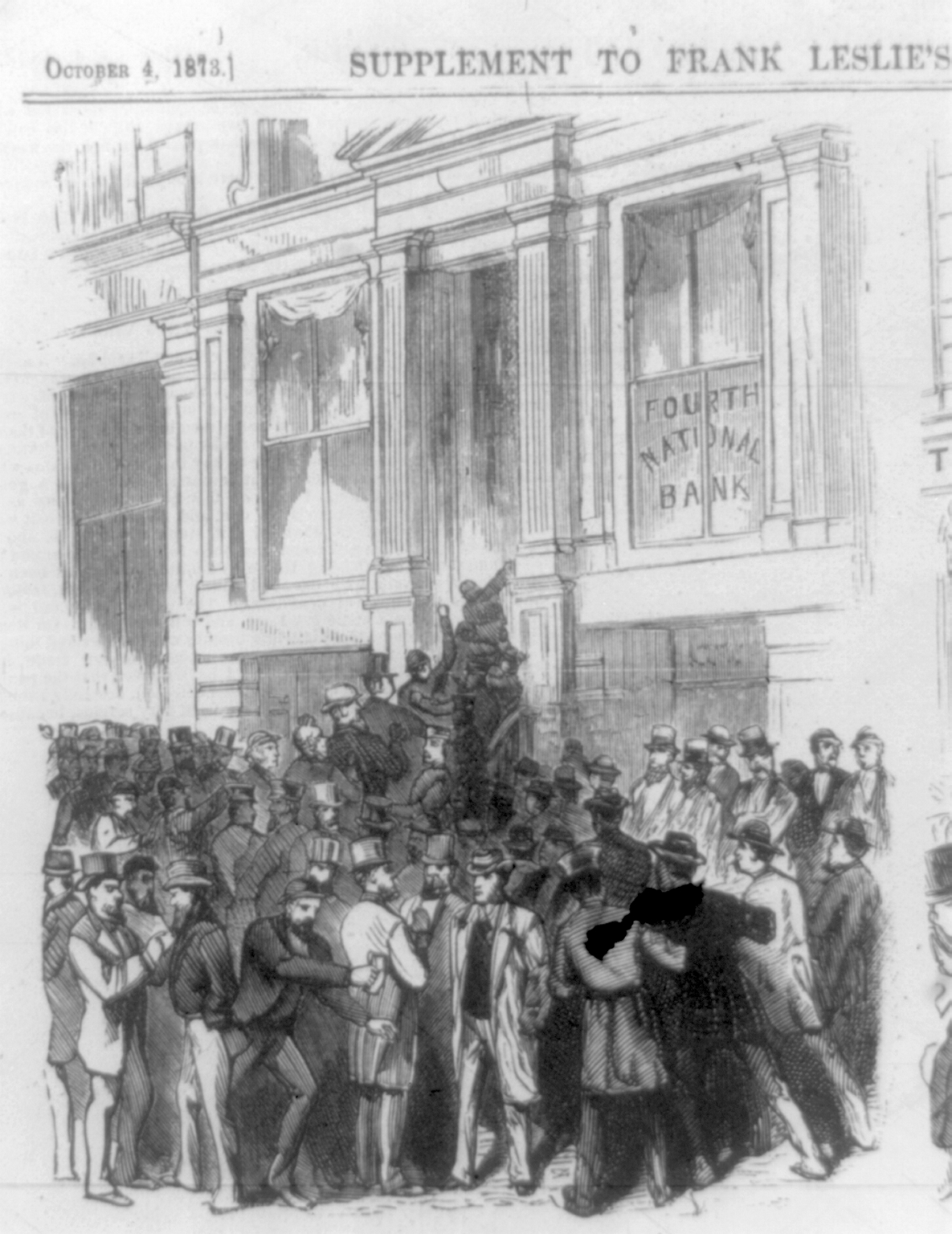

Thousands of American businesses failed, defaulting on more than a billion dollars of debt. One in four laborers in New York were out of work in the winter of 1873–1874 and, nationally, a million became unemployed.

The sectors which experienced the most severe declines in output were manufacturing, construction, and railroads. The railroads had been a tremendous engine of growth in the years before the crisis, yielding a 50% increase in railroad mileage from 1867 to 1873. After absorbing as much as 20% of US capital investment in the years preceding the crash, this expansion came to a dramatic end in 1873; between 1873 and 1878, the total amount of railroad mileage in the United States barely increased at all.

The Freedman's Savings Bank

The Freedman's Saving and Trust Company, known as the Freedman's Savings Bank, was a private savings bank chartered by the U.S. Congress on March 3, 1865, to collect deposits from the newly emancipated communities. The bank opened 37 branches acro ...

was a typical casualty of the financial crisis. Chartered in 1865 in the aftermath of the American Civil War, the bank had been established to advance the economic welfare of America's newly emancipated freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), abolitionism, emancipation (gra ...

. In the early 1870s, the bank had joined in the speculative fever, investing in real estate

Real estate is property consisting of land and the buildings on it, along with its natural resources such as crops, minerals or water; immovable property of this nature; an interest vested in this (also) an item of real property, (more general ...

and unsecured loans to railroads; its collapse in 1874 was a severe blow to African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

.

The recession exacted a harsh political toll on President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

. Historian Allan Nevins

Joseph Allan Nevins (May 20, 1890 – March 5, 1971) was an American historian and journalist, known for his extensive work on the history of the Civil War and his biographies of such figures as Grover Cleveland, Hamilton Fish, Henry Ford, and J ...

says of the end of Grant's presidency: Nevins, Allan, ''Hamilton Fish: The Inner History of the Grant Administration'' (1936online edition

2:811 Recovery began in 1878. The mileage of railroad track laid down increased from in 1878 to 11,568 in 1882. Construction began recovery by 1879; the value of building permits increased two and a half times between 1878 and 1883, and unemployment fell to 2.5% in spite of (or perhaps facilitated by) high immigration. The recovery, however, proved short-lived. Business profits declined steeply between 1882 and 1884. The recovery in railroad construction reversed itself, falling from of track laid in 1882 to of track laid in 1885; the price of steel rails collapsed from $71/ton in 1880 to $20/ton in 1884. Manufacturing again collapsed - durable goods output fell by a quarter again. The decline became another financial crisis in 1884, when multiple New York banks collapsed; simultaneously, in 1883–1884, tens of millions of dollars of foreign-owned American securities were sold out of fears that the United States was preparing to abandon the gold standard. This financial panic destroyed eleven New York banks, more than a hundred state banks, and led to defaults on at least $32 million worth of debt. Unemployment, which had stood at 2.5% between recessions, surged to 7.5% in 1884–1885, and 13% in the northeastern United States, even as immigration plunged in response to deteriorating labor markets. This second recession led to further deterioration of farm prices.

Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

farmers burned their own corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

in 1885 because it was worth less than other fuels such as coal or wood. The country began to recover in 1885.

Reactions to the crisis

Protectionism

The period preceding the Long Depression had been one of increasing economic internationalism, championed by efforts such as theLatin Monetary Union

The Latin Monetary Union (LMU) was a 19th-century system that unified several European currencies into a single currency that could be used in all member states when most national currencies were still made out of gold and silver. It was establish ...

, many of which then were derailed or stunted by the impacts of economic uncertainty. The extraordinary collapse of farm prices provoked a protectionist response in many nations. Rejecting the free trade policies of the Second Empire Second Empire may refer to:

* Second British Empire, used by some historians to describe the British Empire after 1783

* Second Bulgarian Empire (1185–1396)

* Second French Empire (1852–1870)

** Second Empire architecture, an architectural styl ...

, French president

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is ...

Adolphe Thiers

Marie Joseph Louis Adolphe Thiers ( , ; 15 April 17973 September 1877) was a French statesman and historian. He was the second elected President of France and first President of the French Third Republic.

Thiers was a key figure in the July Rev ...

led the new Third Republic to protectionism, which led ultimately to the stringent Méline tariff The Méline tariff was a French protectionist measure introduced in 1892. It is noted as being the most important piece of economic legislation of the Third Republic and marked a return to earlier protectionist policies effectively ending the perio ...

in 1892. Germany's agrarian Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

aristocracy, under attack by cheap, imported grain, successfully agitated for a protective tariff in 1879 in Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

's Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

over the protests of his National Liberal Party allies. In 1887, Italy and France embarked on a bitter tariff war

A trade war is an economic conflict often resulting from extreme protectionism in which states raise or create tariffs or other trade barriers against each other in response to trade barriers created by the other party. If tariffs are the exclus ...

. In the United States, Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

won the 1888 US presidential election on a protectionist pledge.

As a result of the protectionist policies enacted by the world's major trading nations, the global merchant marine fleet posted no significant growth from 1870 to 1890 before it nearly doubled in tonnage in the prewar economic boom that followed. Only the United Kingdom and the Netherlands remained committed to low tariffs.

Monetary responses

In 1874, a year after the 1873 crash, theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

passed legislation called the Inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

Bill of 1874 designed to confront the issue of falling prices by injecting fresh greenbacks into the money supply. Under pressure from business interests, President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

ed the measure. In 1878, Congress overrode President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

's veto to pass the Silver Purchase Act

The Sherman Silver Purchase Act was a United States federal law

enacted on July 14, 1890.Charles Ramsdell Lingley, ''Since the Civil War'', first edition: New York, The Century Co., 1920, ix–635 p., . Re-issued: Plain Label Books, unknown date, ...

, a similar but more successful attempt to promote "easy money".

Strikes

The United States endured its first nationwide strike in 1877, theGreat Railroad Strike of 1877

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877, sometimes referred to as the Great Upheaval, began on July 14 in Martinsburg, West Virginia, after the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) cut wages for the third time in a year. This strike finally ended 52 day ...

. This led to widespread unrest and often violence in many major cities and industrial hubs including Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

, Reading

Reading is the process of taking in the sense or meaning of Letter (alphabet), letters, symbols, etc., especially by Visual perception, sight or Somatosensory system, touch.

For educators and researchers, reading is a multifaceted process invo ...

, Saint Louis, Scranton

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 U ...

, and Shamokin.

New Imperialism

The Long Depression contributed to the revival ofcolonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

leading to the New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

period, symbolized by the scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonisation of Africa, colonization of most of Africa by seven Western Europe, Western European powers during a ...

, as the western powers sought new markets for their surplus accumulated capital. According to Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt (, , ; 14 October 1906 – 4 December 1975) was a political philosopher, author, and Holocaust survivor. She is widely considered to be one of the most influential political theorists of the 20th century.

Arendt was born ...

's ''The Origins of Totalitarianism

''The Origins of Totalitarianism'', published in 1951, was Hannah Arendt's first major work, wherein she describes and analyzes Nazism and Stalinism as the major totalitarian political movements of the first half of the 20th century.

History

...

'' (1951), the "unlimited expansion of power" followed the "unlimited expansion of capital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

".

In the United States, beginning in 1878, the rebuilding, extending, and refinancing of the western railways, commensurate with the wholesale giveaway of water, timber, fish, minerals in what had previously been Indian territory, characterized a rising market. This led to the expansion of markets and industry, together with the robber barons of railroad owners, which culminated in the genteel 1880s and 1890s. The Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

was the outcome for the few rich. The cycle repeated itself with the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

, another huge market crash.

Recovery

In the United States, the National Bureau of Economic Analysis dates the recession through March 1879. In January 1879, the United States returned to the gold standard which it had abandoned during the Civil War; according to economist Rendigs Fels, the gold standard put a floor to the deflation, and this was further boosted by especially good agricultural production in 1879. The view that a single recession lasted from 1873 to 1896 or 1897 is not supported by most modern reviews of the period. It has even been suggested that the trough of this business cycle may have occurred as early as 1875. In fact, from 1869 to 1879, the US economy grew at a rate of 6.8% for real net national product (NNP) and 4.5% for real NNP per capita. Real wages were flat from 1869 to 1879, while from 1879 to 1896, nominal wages rose 23% and prices fell 4.2%.Explanations

Irving Fisher

Irving Fisher (February 27, 1867 – April 29, 1947) was an American economist, statistician, inventor, eugenicist and progressive social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt def ...

believed that the Panic of 1873 and the severity of the contractions which followed it could be explained by debt and deflation and that a financial panic

A financial crisis is any of a broad variety of situations in which some financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many financial crises were associated with banking panics, and man ...

would trigger catastrophic deleveraging

At the micro-economic level, deleveraging refers to the reduction of the leverage ratio, or the percentage of debt in the balance sheet of a single economic entity, such as a household or a firm. It is the opposite of leveraging, which is the prac ...

in an attempt to sell assets and increase capital reserves; that selloff would trigger a collapse in asset prices and deflation

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% (a negative inflation rate). Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but sudden deflation ...

, which would in turn prompt financial institutions to sell off more assets, only to further deflation and strain capital ratio Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) is also known as ''Capital to Risk (Weighted) Assets Ratio'' (CRAR), is the ratio of a bank's Financial capital, capital to its risk. Bank regulation, National regulators track a bank's CAR to ensure that it can absorb ...

s. Fisher believed that had governments or private enterprise embarked on efforts to reflate financial markets, the crisis would have been less severe.

David Ames Wells

David Ames Wells (June 17, 1828 – November 5, 1898) was an American engineer, textbook author, economist and advocate of low tariffs.

Born in Springfield, Massachusetts, he graduated from Williams College in 1847. In 1848 he joined the staff ...

(1890) wrote of the technological advancements during the period 1870–90, which included the Long Depression. Wells gives an account of the changes in the world economy transitioning into the Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Firs ...

in which he documents changes in trade, such as triple expansion steam shipping, railroads, the effect of the international telegraph network and the opening of the Suez Canal. Wells gives numerous examples of productivity

Productivity is the efficiency of production of goods or services expressed by some measure. Measurements of productivity are often expressed as a ratio of an aggregate output to a single input or an aggregate input used in a production proces ...

increases in various industries and discusses the problems of excess capacity and market saturation.

Wells' opening sentence:

The economic changes that have occurred during the last quarter of a century - or during the present generation of living men - have unquestionably been more important and more varied than during any period of the world's history.Other changes Wells mentions are reductions in warehousing and inventories, elimination of middlemen,

economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables ...

, the decline of craftsmen, and the displacement of agricultural workers. About the whole 1870–90 period Wells said:

Some of these changes have been destructive, and all of them have inevitably occasioned, and for a long time yet will continue to occasion, great disturbances in old methods, and entail losses of capital and changes in occupation on the part of individuals. And yet the world wonders, and commissions of great states inquire, without coming to definite conclusions, why trade and industry in recent years has been universally and abnormally disturbed and depressed.Wells notes that many of the government inquiries on the "depression of prices" (deflation) found various reasons such as the scarcity of gold and silver. Wells showed that the US money supply actually grew over the period of the deflation. Wells noted that deflation lowered the cost of only goods that benefited from improved methods of manufacturing and transportation. Goods produced by craftsmen and many services did not decrease in value, and the cost of labor actually increased. Also, deflation did not occur in countries that did not have modern manufacturing, transportation, and communications. Nobel laureate economist

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

, author of ''A Monetary History of the United States

''A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960'' is a book written in 1963 by Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman and Anna J. Schwartz. It uses historical time series and economic analysis to argue the then-novel proposition th ...

'', on the other hand, blamed this prolonged economic crisis on the imposition of a new gold standard, part of which he referred to by its traditional name, The Crime of 1873. Additionally, Friedman pointed to the expansion of the gold supply through Gold cyanidation

Gold cyanidation (also known as the cyanide process or the MacArthur-Forrest process) is a hydrometallurgical technique for extracting gold from low-grade ore by converting the gold to a water-soluble coordination complex. It is the most commonly ...

as a contributor to the recovery. This forced shift into a currency whose supply was limited by nature, unable to expand with demand, caused a series of economic and monetary contractions that plagued the entire period of the Long Depression. Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian m ...

, in his book ''History of Money and Banking of the United States'', argues that the long depression was only a misunderstood recession since real wages and production were actually increasing throughout the period. Like Friedman, he attributes falling prices to the resumption of a deflationary gold standard in the U.S. after the Civil War.

Interpretations

Most economic historians see this period as negative for the most industrial nations. Many argue that most of the stagnation was caused by a monetary contraction caused by abandonment of thebimetallic standard

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

, in favor of a new fiat gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

, starting with the Coinage Act of 1873

The Coinage Act of 1873 or Mint Act of 1873, was a general revision of laws relating to the Mint of the United States. By ending the right of holders of silver bullion to have it coined into standard silver dollars, while allowing holders of go ...

.

Other economic historians have complained about the characterization of this period as a "depression" because of conflicting economic statistics that cast doubt on this interpretation. They note it saw a relatively large expansion of industry, of railroads, of physical output, of net national product, and of real per capita income.

As economists Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and Anna J. Schwartz

Anna Jacobson Schwartz (pronounced ; November 11, 1915 – June 21, 2012) was an American economist who worked at the National Bureau of Economic Research in New York City and a writer for ''The New York Times''. Paul Krugman has said that Schwar ...

have noted, the decade from 1869 to 1879 saw a growth of 3 percent per year in money national product, an outstanding real national product growth of 6.8 percent per year, and a rise of 4.5 percent per year in real product per capita. Even the alleged "monetary contraction" never took place, the money supply increasing by 2.7 percent per year. From 1873 through 1878, before another spurt of monetary expansion, the total supply of bank money rose from $1.964 billion to $2.221 billion, a rise of 13.1 percent, or 2.6 percent per year. In short, it was a modest but definite rise, not a contraction.Friedman, Schwartz. A Monetary History of the United States: 1867–1960. Although per-capita nominal income declined very gradually from 1873 to 1879, that decline was more than offset by a gradual increase over the course of the next 17 years.

Furthermore, real per capita income either stayed approximately constant (1873–1880; 1883–1885) or rose (1881–1882; 1886–1896), so the average consumer appears to have been considerably better off at the end of the "depression" than before. Studies of other countries where prices also tumbled, including the US, Germany, France, and Italy, reported more markedly positive trends in both nominal and real per capita income figures. Profits generally were also not adversely affected by deflation, although they declined (particularly in Britain) in industries struggling against superior, foreign competition. Furthermore, some economists argue a falling general price level is not inherently harmful to an economy and cite the economic growth of the period as evidence.Murray N. Rothbard"A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II"

(pdf), The War of 1812 and its Aftermath, p.145, 153-156. As economist

Murray Rothbard

Murray Newton Rothbard (; March 2, 1926 – January 7, 1995) was an American economist of the Austrian School, economic historian, political theorist, and activist. Rothbard was a central figure in the 20th-century American libertarian m ...

has stated:

Unfortunately, most historians and economists are conditioned to believe that steadily and sharply falling prices must result in depression: hence their amazement at the obvious prosperity and economic growth during this era. For they have overlooked the fact that in the natural course of events, when government and the banking system do not increase the money supply very rapidly, freemarket capitalism will result in an increase of production and economic growth so great as to swamp the increase of money supply. Prices will fall, and the consequences will be not depression or stagnation, but prosperity (since costs are falling, too), economic growth, and the spread of the increased living standard to all the consumers.Accompanying the overall growth in real prosperity was a marked shift in consumption from necessities to luxuries: by 1885, "more houses were being built, twice as much tea was being consumed, and even the working classes were eating imported meat, oranges, and dairy produce in quantities unprecedented". The change in working class incomes and tastes was symbolized by "the spectacular development of the department store and the chain store".

Prices certainly fell, but almost every other index of economic activity - output of coal and pig iron, tonnage of ships built, consumption of raw wool and cotton, import and export figures, shipping entries and clearances, railway freight clearances, joint-stock company formations, trading profits, consumption per head of wheat, meat, tea, beer, and tobacco - all of these showed an upward trend.A.E. MussonA large part at least of the deflation commencing in the 1870s was a reflection of unprecedented advances in factor productivity. Real unit production costs for most final goods dropped steadily throughout the 19th century and especially from 1873 to 1896. At no previous time had there been an equivalent "harvest of technological advances... so general in their application and so radical in their implications". That is why, notwithstanding the dire predictions of many eminent economists, Britain did not end up paralyzed by strikes and lockouts. Falling prices did not mean falling money wages. Instead of inspiring large numbers of workers to go on strike, falling prices were inspiring them to go shopping.George Selgin

"The Great Depression in Britain, 1873–1896: a Reappraisal"

The Journal of Economic History (1959), 19: 199-228

"Less Than Zero - The Case for a Falling Price Level in a Growing Economy"

''The Institute of Economic Affairs'', 1997, p.49-53. Referenced 2011-01-15.

See also

*Crisis theory

Crisis theory, concerning the causes and consequences of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in a capitalist system, is associated with Marxian critique of political economy, and was further popularised through Marxist economics.

Histo ...

* Economic history

Economic history is the academic learning of economies or economic events of the past. Research is conducted using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the application of economic theory to historical situations and ins ...

* Equine Influenza of 1872

* Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

* Great Depression of British Agriculture

The Great Depression of British Agriculture occurred during the late nineteenth century and is usually dated from 1873 to 1896. Contemporaneous with the global Long Depression, Britain's agricultural depression was caused by the dramatic fall in gr ...

(1873-1896)

* Kondratiev wave

In economics, Kondratiev waves (also called supercycles, great surges, long waves, K-waves or the long economic cycle) are hypothesized cycle-like phenomena in the modern world economy. The phenomenon is closely connected with the technology li ...

* List of economic crises

This is a list of economic crises and depressions.

1st century

*Financial crisis of 33.

The result of the mass issuance of unsecured loans by main Roman banking houses.

3rd century

*Crisis of the Third Century

7th century

Coin exchange crisis ...

* List of recessions in the United States

There have been as many as 48 recessions in the United States dating back to the Articles of Confederation, and although economists and historians dispute certain 19th-century recessions, the consensus view among economists and historians is that ...

* New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

* Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

* Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

* Second Industrial Revolution

The Second Industrial Revolution, also known as the Technological Revolution, was a phase of rapid scientific discovery, standardization, mass production and industrialization from the late 19th century into the early 20th century. The Firs ...

Footnotes

Further reading

* Samuel Bernstein, "American Labor in the Long Depression, 1873–1878," ''Science and Society'', vol. 20, no. 1 (Winter 1956), pp. 59–83In JSTOR

{{Reconstruction Era 1873 establishments 1896 disestablishments Economic collapses Recessions Late modern Europe 19th-century economic history 1870s economic history 1880s economic history 1890s economic history 1873 in economics