Deportation Of The Meskhetian Turks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The deportation of the Meskhetian Turks (russian: Депортация турок-месхетинцев) was the

The

The

On 31 July 1944, the Soviet

On 31 July 1944, the Soviet  4,000 NKVD agents were appointed to carry out the operation. Like the previous deportations, this one was also supervised by the NKVD chief

4,000 NKVD agents were appointed to carry out the operation. Like the previous deportations, this one was also supervised by the NKVD chief

Beria sent a memorandum to Stalin on 28November 1944, in which he accused the Meskhetian Turks of "smuggling" and of being "used by

Beria sent a memorandum to Stalin on 28November 1944, in which he accused the Meskhetian Turks of "smuggling" and of being "used by

The Meskhetian Turks were placed under the administration of the special settlements. The purpose of these settlements was to be a system of cheap labor for the economic progress of faraway parts of the Soviet Union. Many of those deported performed

The Meskhetian Turks were placed under the administration of the special settlements. The purpose of these settlements was to be a system of cheap labor for the economic progress of faraway parts of the Soviet Union. Many of those deported performed

Stalin's successor, the new Soviet leader

Stalin's successor, the new Soviet leader  The situation changed, at least on paper, in the late 1980s when the new Soviet leader,

The situation changed, at least on paper, in the late 1980s when the new Soviet leader,

Meskhetians or Meskhetian Turks - Minority Rights Group

1944 in the Soviet Union Ethnic cleansing in Europe

forced transfer

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

by the Soviet government

The Government of the Soviet Union ( rus, Прави́тельство СССР, p=prɐˈvʲitʲɪlʲstvə ɛs ɛs ɛs ˈɛr, r=Pravítelstvo SSSR, lang=no), formally the All-Union Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, commonly ab ...

of the entire Meskhetian Turk

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, ( ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti regio ...

population from the Meskheti

Meskheti ( ka, მესხეთი) or Samtskhe ( ka, სამცხე) (Moschia in ancient sources), is a mountainous area in southwestern Georgia.

History

Ancient tribes known as the Mushki (or Moschi) and Mosiniks (or Mossynoeci) were the ...

region of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

(now Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

) to Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

on 14November 1944. During the deportation, between 92,307 and 94,955 Meskhetian Turks were forcibly removed from 212 villages. They were packed into cattle wagon

A cattle wagon or a livestock wagon is a type of railway vehicle designed to carry livestock. Within the classification system of the International Union of Railways they fall under Class H - special covered wagons - which, in turn are part of the ...

s and mostly sent to the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз� ...

. Members of other ethnic groups were also deported during the operation, including Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ir ...

and Hemshins, bringing the total to approximately 115,000 evicted people. They were placed in special settlements where they were assigned to forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. The deportation and harsh conditions in exile caused between 12,589 to 50,000 deaths.

The expulsion was executed by NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

chief Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

on the orders of Soviet Premier

The Premier of the Soviet Union (russian: Глава Правительства СССР) was the head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The office had four different names throughout its existence: Chairman of the ...

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

and involved 4,000 NKVD personnel. 34 million roubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

were allocated to carry out the operation. It was a part of the Soviet forced settlement program and population transfers

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to Development-induced displacement, economic deve ...

that affected several million members of Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s. Around 32,000 people, mostly Armenians, were settled by the Soviet government in the areas cleared of Meskhetia.

After Stalin's death, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

delivered a secret speech in 1956 in which he condemned and reversed Stalin's deportations of various ethnic groups, many of which were allowed to their places of origin. However, even though they were released from the special settlements, the Meskhetian Turks, along with the Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace

...

and Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (german: Wolgadeutsche, ), russian: поволжские немцы, povolzhskiye nemtsy) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov ...

, were forbidden from returning to their native lands, making their exile permanent. Due to the secrecy of their expulsion and the politics of the Soviet Union, the deportation of the Meskhetian Turks remained relatively unknown and was subject to very little scholarly research until they were targeted by violent riots in Uzbekistan in 1989. Modern historians categorized the crime as ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

and a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the c ...

. In 1991, the newly independent Georgia refused to give Meskhetian Turks the right to return to the Meskheti region. The Meskhetian Turks numbered between 260,000 and 335,000 people in 2006, and are today scattered across seven countries of the former Soviet Union

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

, where many are stateless.

Background

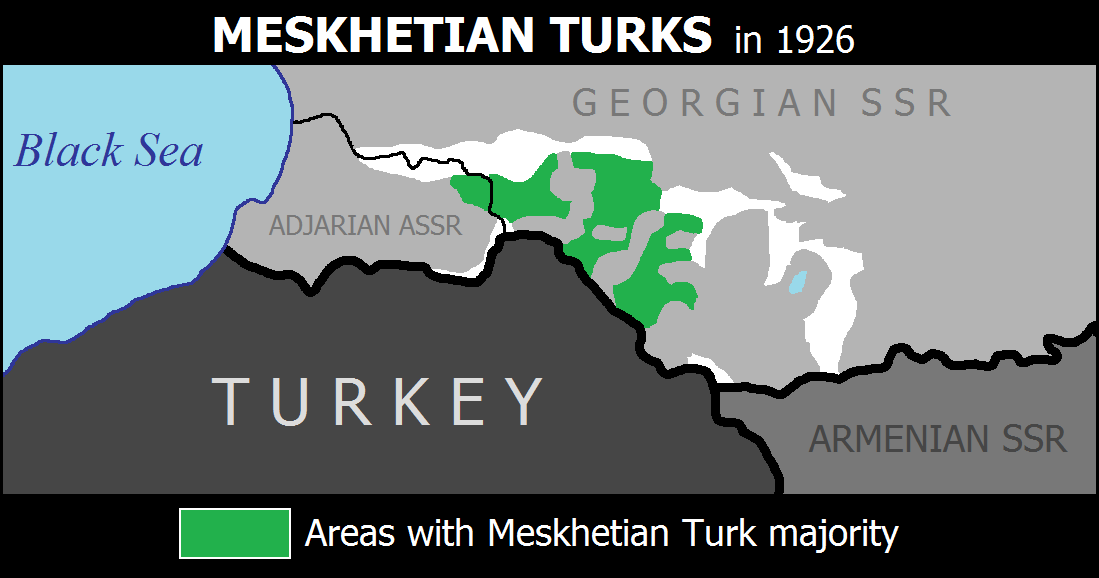

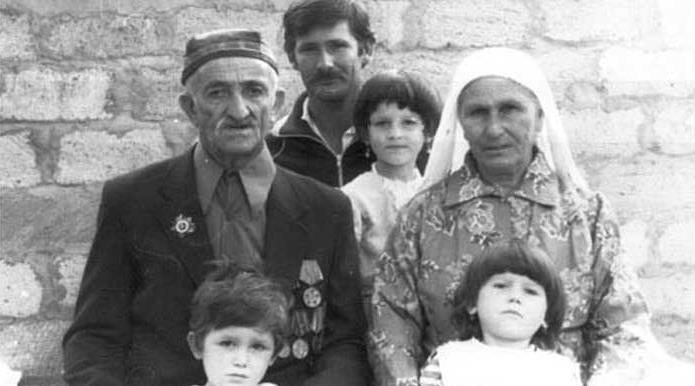

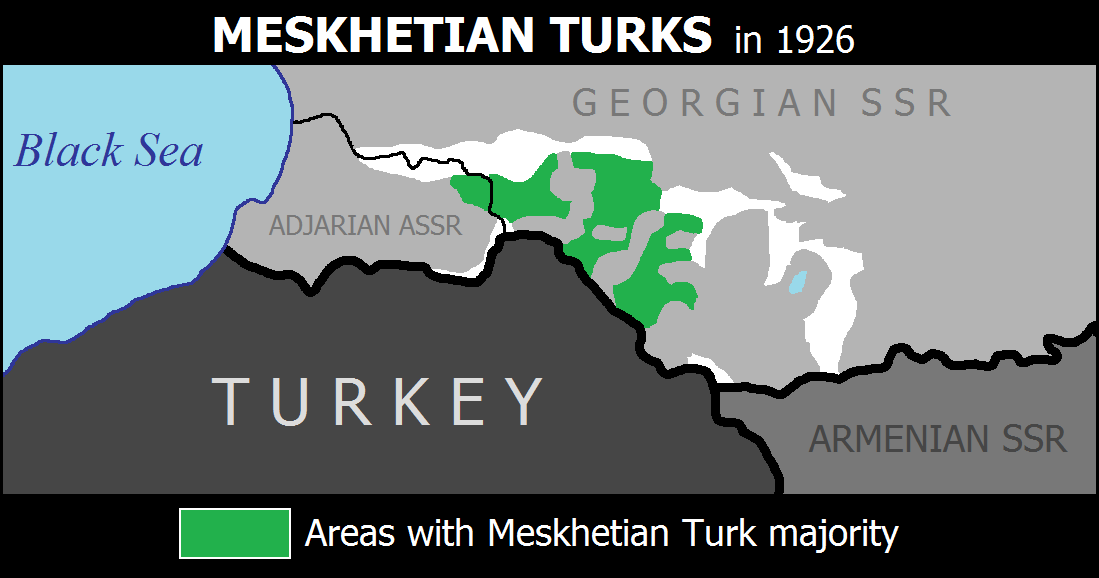

Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, ( ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti regio ...

, also known as Akhiska Turks, originally lived in the Meskheti

Meskheti ( ka, მესხეთი) or Samtskhe ( ka, სამცხე) (Moschia in ancient sources), is a mountainous area in southwestern Georgia.

History

Ancient tribes known as the Mushki (or Moschi) and Mosiniks (or Mossynoeci) were the ...

region in the south of present-day Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. There is no consensus among historians regarding their origin. Either they are ethnic Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic languages

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic o ...

or Turkicized

Turkification, Turkization, or Turkicization ( tr, Türkleştirme) describes a shift whereby populations or places received or adopted Turkic attributes such as culture, language, history, or ethnicity. However, often this term is more narrowly ...

Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, G ...

who converted to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

during the Ottoman rule of the region.

The Ottoman army conquered the Meskheti region, then part of the Principality of Samtskhe

The Samtskhe-Saatabago or Samtskhe Atabegate ( ka, სამცხე-საათაბაგო), also called the Principality of Samtskhe (სამცხის სამთავრო), was a Georgian feudal principality in Zemo Kartli, ru ...

, during the Turkish military expedition of 1578. Turkish historians are of the view that the Turkic tribes had settled in the region as early as the eleventh and twelfth centuries when Georgian king David IV invited the Kipchaks

The Kipchaks or Qipchaks, also known as Kipchak Turks or Polovtsians, were a Turkic nomadic people and confederation that existed in the Middle Ages, inhabiting parts of the Eurasian Steppe. First mentioned in the 8th century as part of the Se ...

Turkic tribes to defend his border regions from the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; fa, سلجوقیان ''Saljuqian'', alternatively spelled as Seljuqs or Saljuqs), also known as Seljuk Turks, Seljuk Turkomans "The defeat in August 1071 of the Byzantine emperor Romanos Diogenes

by the Turk ...

. The area became part of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

in 1829 following the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histor ...

.

In 1918, near the end of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and at the beginning of the Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

, Georgia proclaimed independence, while some Muslim communities in Meskheti proclaimed a semi-autonomous confederation and prepared for a unification with the dissolving Ottoman Empire. Ottoman troops moved into this area and numerous clashes broke out between the Christian and Muslim populations of the region. In 1921 Soviet forces took control of Georgia and signed the Treaty of Kars

The Treaty of Kars ( tr, Kars Antlaşması, rus, Карсский договор, Karskii dogovor, ka, ყარსის ხელშეკრულება, hy, Կարսի պայմանագիր, az, Qars müqaviləsi) was a treaty that est ...

which divided Meskheti between Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

and the newly Soviet Georgia

The Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (Georgian SSR; ka, საქართველოს საბჭოთა სოციალისტური რესპუბლიკა, tr; russian: Грузинская Советская Соц� ...

. In the 1920s, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

emerged as the new General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

A general officer is an officer of high rank in the armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colonel."general, adj. and n.". OED O ...

. Ben Kiernan, an American academic and historian, described Stalin's era as "by far the bloodiest of Soviet or even Russian history".

Between 1928 and 1937, the Meskhetian Turks were pressured by the Soviet authorities to adopt Georgian names. The 1926 Soviet census

The 1926 Soviet Census took place in December 1926. It was an important tool in the state-building of the USSR, provided the government with important ethnographic information, and helped in the transformation from Imperial Russian society to Sov ...

listed 137,921 Turks in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, but this figure included Azerbaijanis

Azerbaijanis (; az, Azərbaycanlılar, ), Azeris ( az, Azərilər, ), or Azerbaijani Turks ( az, Azərbaycan Türkləri, ) are a Turkic people living mainly in northwestern Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan. They are the second-most numer ...

. In the 1939 Soviet census, most Meskhetian Turks were classified as Azerbaijanis.

Deportation

On 31 July 1944, the Soviet

On 31 July 1944, the Soviet State Defense Committee

The State Defense Committee (russian: Государственный комитет обороны - ГКО, translit=Gosudarstvennyĭ komitet oborony - GKO) was an extraordinary organ of state power in the USSR during the German-Soviet War (Grea ...

decree N 6277ss stated: "... in order to defend Georgia's state border and the state border of the USSR we are preparing to relocate Turks, Kurds and Hemshils from the border strip". On 23September 1944, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic

; kk, Қазақ Советтік Социалистік Республикасы)

*1991: Republic of Kazakhstan (russian: Республика Казахстан; kk, Қазақстан Республикасы)

, linking_name = the ...

informed the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

that it was ready to accept new settlers: Turks, Kurds, Hemshils; 5,350 families to kolkhoz

A kolkhoz ( rus, колхо́з, a=ru-kolkhoz.ogg, p=kɐlˈxos) was a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union. Kolkhozes existed along with state farms or sovkhoz., a contraction of советское хозяйство, soviet ownership or ...

es and 750 families to sovkhoz

A sovkhoz ( rus, совхо́з, p=sɐfˈxos, a=ru-sovkhoz.ogg, abbreviated from ''советское хозяйство'', "sovetskoye khozyaystvo (sovkhoz)"; ) was a form of state-owned farm in the Soviet Union.

It is usually contrasted wit ...

es. The Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic

Uzbekistan (, ) is the common English name for the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR; uz, Ўзбекистон Совет Социалистик Республикаси, Oʻzbekiston Sovet Sotsialistik Respublikasi, in Russian: Уз� ...

said that it was ready to accept 50,000 people (instead of the planned 30,000). 239 railcars were prepared to transport the deportees and people were mobilized.

The Meskhetian Turks were one of the six ethnic groups from the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

who were deported in 1943 and 1944 in their entirety by the Soviet secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

—the other five were the Chechens

The Chechens (; ce, Нохчий, , Old Chechen: Нахчой, ''Naxçoy''), historically also known as ''Kisti'' and ''Durdzuks'', are a Northeast Caucasian ethnic group of the Nakh peoples native to the North Caucasus in Eastern Europe. "Europ ...

, the Ingush, the Balkars

The Balkars ( krc, Малкъарлыла, Malqarlıla or Таулула, , 'Mountaineers') are a Turkic people of the Caucasus region, one of the titular populations of Kabardino-Balkaria. Their Karachay-Balkar language is of the Ponto-Casp ...

, the Karachays

The Karachays ( krc, Къарачайлыла, Qaraçaylıla or таулула, , 'Mountaineers') are an indigenous Caucasian Turkic ethnic group in the North Caucasus. They speak Karachay-Balkar, a Turkic language. They are mostly situated ...

and the Kalmyks

The Kalmyks ( Kalmyk: Хальмгуд, ''Xaľmgud'', Mongolian: Халимагууд, ''Halimaguud''; russian: Калмыки, translit=Kalmyki, archaically anglicised as ''Calmucks'') are a Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in Russia, w ...

. Their deportation was relatively poorly documented. Historians date the expulsion of the Meskhetian Turks to Soviet Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a subregion, region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes t ...

either to 14 or 15November 1944. The operation was completed by 26 November. At the start of the operation, the Soviet soldiers arrived as early as 4:00 a.m. at the homes of the Meskhetian Turks and did not tell them were they were being taken to. The population was not given advance notice; the NKVD notification stated: "You are to be deported. Get ready. Take foodstuffs for three days. Two hours for preparation." Studebaker trucks were used to drive the Meskhetian Turks to the nearby railway stations. In the deportation, between 92,307 and 94,955 Meskhetian Turks, distributed in 16,700 families, were forcibly resettled from 212 villages. They were packed into cattle wagon

A cattle wagon or a livestock wagon is a type of railway vehicle designed to carry livestock. Within the classification system of the International Union of Railways they fall under Class H - special covered wagons - which, in turn are part of the ...

s and deported eastwards to Central Asia. By 4:00 p.m. on 17November, 81,234 people had been dispatched.

Official Soviet records indicate that 92,307 persons were deported, of whom 18,923 were men, 27,309 were women and 45,989 were children under the age of 16. 52,163 were resettled in the Uzbek SSR, 25,598 in the Kazakh SSR and 10,546 in the Kyrgiz SSR. 84,556 people were employed in kolkhozes, 6,316 in sovkhozes and 1,395 in industrial enterprises. The last of the deported people arrived at Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of ...

by 31January 1945.

Deported Meskhetian Turks were allowed to carry up to of personal belongings with them per family, twice the amount as Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace

...

during their previous deportation. Members of other minority ethnic groups were also deported with the Meskhetian Turks, including Kurds ug:كۇردلار

Kurds ( ku, کورد ,Kurd, italic=yes, rtl=yes) or Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group native to the mountainous region of Kurdistan in Western Asia, which spans southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Ir ...

and Hemshils (Armenian Muslims), giving a total of approximately 115,000 evicted persons. One source indicates that 8,694 Kurds and 1,385 Hemshils were deported as part of the operation. Only women married to men of other, non-deported ethnic groups were spared. Each family was given two hours to collect their belongings for the trip. Seven families were loaded into each boxcar

A boxcar is the North American ( AAR) term for a railroad car that is enclosed and generally used to carry freight. The boxcar, while not the simplest freight car design, is considered one of the most versatile since it can carry most ...

, 20-25 families into each carriage. Like the other groups from the Caucasus, they were transported several thousand miles, to Central Asia. They were sealed off in these cattle wagons for a month.

4,000 NKVD agents were appointed to carry out the operation. Like the previous deportations, this one was also supervised by the NKVD chief

4,000 NKVD agents were appointed to carry out the operation. Like the previous deportations, this one was also supervised by the NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria (; rus, Лавре́нтий Па́влович Бе́рия, Lavréntiy Pávlovich Bériya, p=ˈbʲerʲiə; ka, ლავრენტი ბერია, tr, ; – 23 December 1953) was a Georgian Bolshevik ...

. It was ordered by the Premier of the Soviet Union Joseph Stalin. Stalin allocated 34 million roubles

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

to the NKVD in order to carry it out. It was part of the Soviet forced settlement program and population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is a ...

that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

alone, 3,332,589 persons were deported in the Soviet Union. Throughout the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, about 650,000 people were deported in 1943 and 1944.

This was the last Soviet deportation during World War II. Until 1956, the Soviet authorities denied the Meskhetian Turks any civic or political rights. Around 32,000 people, mostly Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, were settled by the Soviet authorities in the cleared areas.

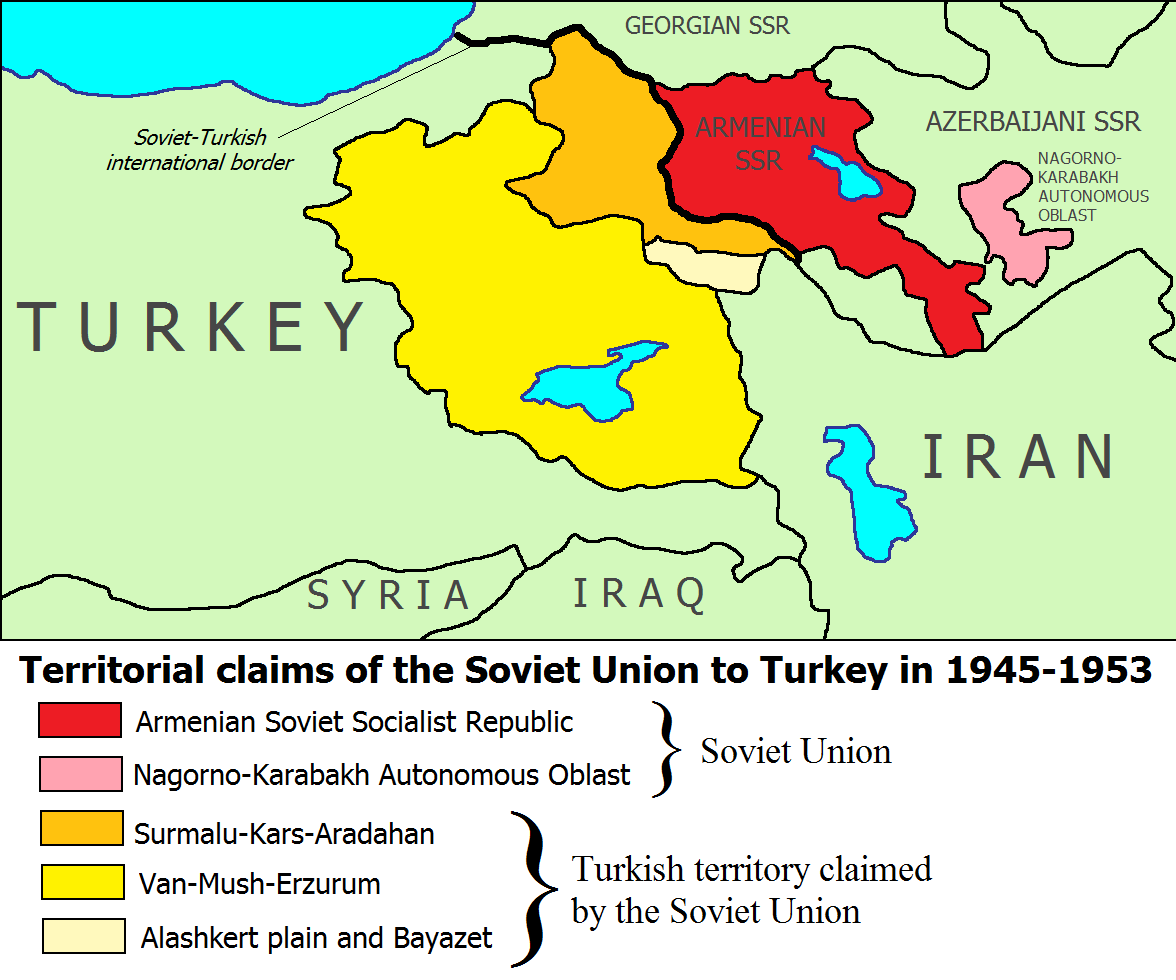

Possible reasons

Unlike the other five ethnic groups of the Caucasus who were accused of Axis collaboration during World War II, the Meskhetian Turks were never officially charged by the Soviet government with any crime; they were not close to any combat. In spite of this, they were deported as well. The German army never came within a range of 100 miles of the Meskheti region. ProfessorBrian Glyn Williams

Brian Glyn Williams is a professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth who worked for the CIA. As an undergraduate, he attended Stetson University, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts in 1988. He received his PhD in Mi ...

concluded that the deportations of Meskhetian Turks, which coincided with the deportation of other ethnic groups from Caucasus and Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a pop ...

, lends the strongest evidence that all the deportations were a part of a larger concealed Soviet foreign policy rather than a response to any "universal mass treason" of these people. Svante Cornell

Svante E. Cornell (born 1975) is a Swedish scholar specializing on politics and security issues in Eurasia, especially the South Caucasus, Turkey, and Central Asia. He is a director and co-founder of the Stockholm-based Institute for Security and ...

pointed out that the eviction was a part of a larger Russian policy that had been in effect since 1864: to remove as many Muslim minorities from the Caucasus as possible.

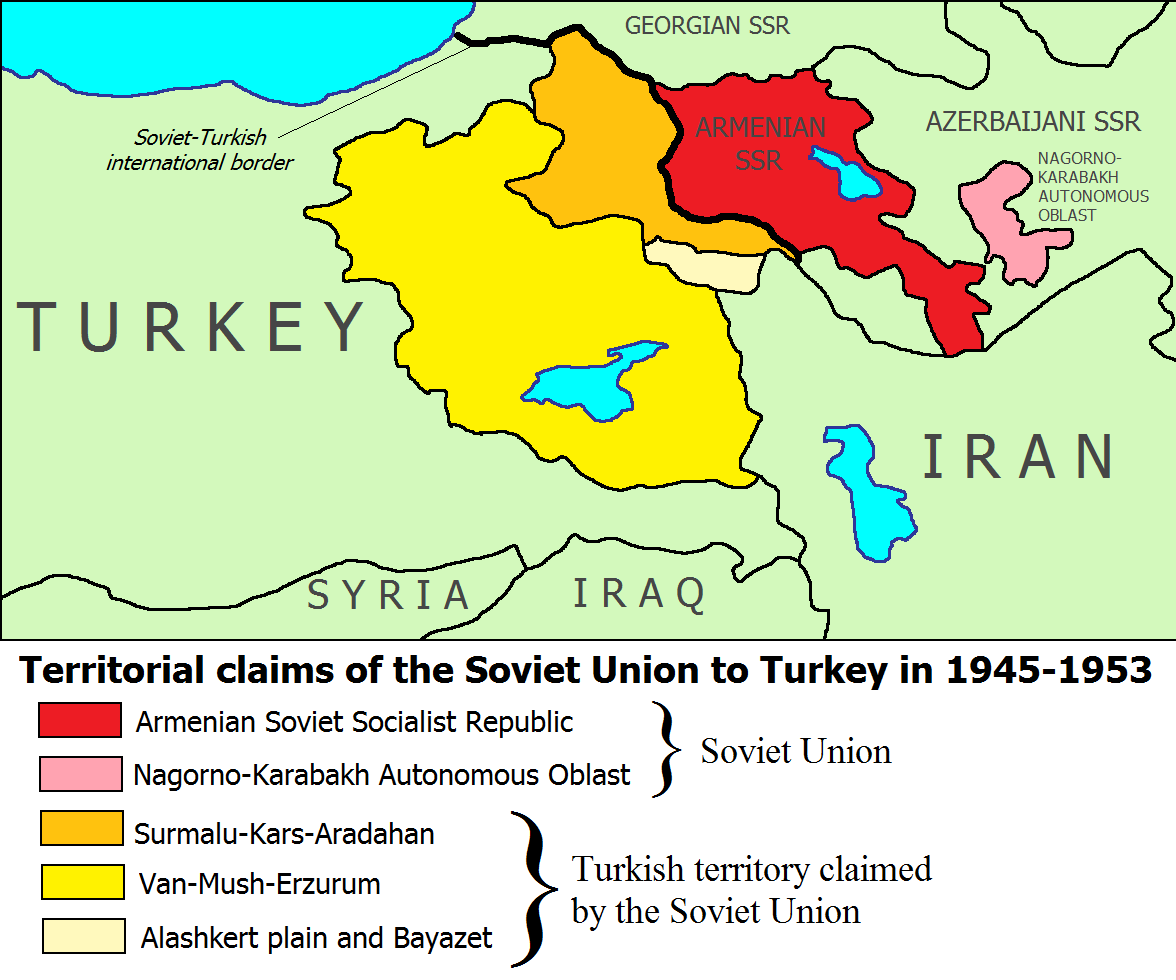

Beria sent a memorandum to Stalin on 28November 1944, in which he accused the Meskhetian Turks of "smuggling" and of being "used by

Beria sent a memorandum to Stalin on 28November 1944, in which he accused the Meskhetian Turks of "smuggling" and of being "used by Turkish intelligence

The National Intelligence Organization ( tr, Millî İstihbarat Teşkilatı, MİT) is the state intelligence agency of Turkey.

Established in 1965 to replace National Security Service (Turkey), National Security Service, its aim is to gather i ...

for espionage". Beria's secret decree painted the Meskhetian Turks, the Kurds and the Hemshils as "untrustworthy population" that must be removed from the border region. Some historians interpret this eviction by Stalin's plan to remove the pro-Turkish group from the border area in order to obtain parts of northeastern Turkey. In June 1945, Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

, the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs, demanded of Turkey that it cedes three Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

n provinces to the Soviet Union: Kars

Kars (; ku, Qers; ) is a city in northeast Turkey and the capital of Kars Province. Its population is 73,836 in 2011. Kars was in the ancient region known as ''Chorzene'', (in Greek Χορζηνή) in classical historiography ( Strabo), part of ...

, Ardahan

Ardahan (, ka, არტაანი, tr, hy, Արդահան, translit=Ardahan Russian: Ардаган) is a city in northeastern Turkey, near the Georgian border.

It is the capital of Ardahan Province.

History

Ancient and medieval

Ardahan ...

and Artvin

Artvin (Laz language, Laz and ; hy, Արտուին, translit=Artuin) is a List of cities in Turkey, city in northeastern Turkey about inland from the Black Sea.

It is located on a hill overlooking the Çoruh, Çoruh River near the Deriner Dam ...

. Scholars Alexandre Bennigsen

Alexandre Bennigsen (russian: Александр Адамович Беннигсен) (20 March 1913 – 3 June 1988) was a scholar of Islam in the Soviet Union.

Biography

Count Bennigsen was born in an aristocratic family in St Petersburg ...

and Marie Broxup

Marie Bennigsen-Broxup (1944 – 7 December 2012) was an expert on the Caucasus and Central Asia, with particular emphasis on Muslim communities within these regions. She pioneered an area studies focus on the former Soviet south, founding new res ...

concluded that the deportation of the Meskhetian Turks was thus undertaken as a precaution in case of a Soviet-Turkish war for eastern parts of Turkey. These claims, and the Turkish Straits crisis, escalated, until the plans failed when Turkey joined NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

in 1951.

The Soviet authorities tried to forge a state out of 108 different nationalities. Initially they tried to use this multiethnic state

A multinational state or a multinational union is a sovereign entity that comprises two or more nations or states. This contrasts with a nation state, where a single nation accounts for the bulk of the population. Depending on the definition of " ...

to exploit cross-border ethnic groups to project influence into the countries neighboring the Soviet Union. Terry Martin, a professor of Russian studies, assessed that this had the opposite effect; the Soviet fear of "capitalist influence" eventually led to ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, and religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making a region ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal, extermination, deportation or population transfer ...

of its borderlands, which encompassed the Meskhetian Turks.

Death toll

The Meskhetian Turks were placed under the administration of the special settlements. The purpose of these settlements was to be a system of cheap labor for the economic progress of faraway parts of the Soviet Union. Many of those deported performed

The Meskhetian Turks were placed under the administration of the special settlements. The purpose of these settlements was to be a system of cheap labor for the economic progress of faraway parts of the Soviet Union. Many of those deported performed forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. Special settlers routinely worked eleven to twelve hours a day, seven days a week. They suffered from exhaustion and frostbite, and were denied their food rations if they did not meet their work quota. The lack of food was apparently so severe that the Soviet Council of People's Commissars

The Councils of People's Commissars (SNK; russian: Совет народных комиссаров (СНК), ''Sovet narodnykh kommissarov''), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (Совнарком), were the highest executive authorities of ...

adopted the decree N 942 rs which provided of flour

Flour is a powder made by grinding raw grains, roots, beans, nuts, or seeds. Flours are used to make many different foods. Cereal flour, particularly wheat flour, is the main ingredient of bread, which is a staple food for many culture ...

and of cereals

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food en ...

to the settlers from the Georgian SSR. The exiled peoples had to report to their surveillance organs on a weekly basis and were not allowed to travel anywhere outside their settlements. However, Meskhetian Turks were treated somewhat better than other ethnic groups in the special settlements because they had not been accused of a specific crime.

During their first 12 years in the special settlements, the exiled Meskhetian Turks coped with extreme deprivation and isolation from the outside world. They suffered a considerable hardship during the first years in exile. These included poor quality of food and medicine; the process of adaptation to the new climate, epidemics, which included spotted fever

A spotted fever is a type of tick-borne disease which presents on the skin. They are all caused by bacteria of the genus '' Rickettsia''. Typhus is a group of similar diseases also caused by ''Rickettsia'' bacteria, but spotted fevers and typhus ...

, and forced labor.

Estimates of the mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of de ...

of the Meskhetian Turks differ. The Karachay demographer D. M. Ediev estimated that 12,589 Meskhetian Turks died due to the deportation, amounting to a 13 percent mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically expressed in units of de ...

of their entire ethnic group. Professor Michael Rywkin gave a higher figure of 15,000 fatalities among this ethnic group. Official, but incomplete, Soviet archives recorded 14,895 deaths or a 14 percent to 15.7 percent mortality rate among the people deported from the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. This list included all the groups from the region, but the Meskhetian Turks formed a large majority of them. Soviet archives also record that an additional 457 people died during the transit to Central Asia. High assessments give a figure of 30,000 and up to 50,000 dead. By 1948, the mortality rate had fallen to 2.8%.

On 26November 1948 the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Soviet issued a decree which sentenced the deported groups to permanent exile in those distant regions. This decree applied to Chechens and Ingush, Crimean Tatars, Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (german: Wolgadeutsche, ), russian: поволжские немцы, povolzhskiye nemtsy) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov ...

, Balkars, Kalmyks and the Meskhetian Turks.

Aftermath

Stalin's successor, the new Soviet leader

Stalin's successor, the new Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, delivered a secret speech

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" (russian: «О культе личности и его последствиях», «''O kul'te lichnosti i yego posledstviyakh''»), popularly known as the "Secret Speech" (russian: секре ...

at the Communist Party Congress on 24February 1956 condemning the Stalinist deportations, but did not mention the Meskhetian Turks among the deported peoples. The Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, dated 28April 1956 and titled "On the removal of special deportation restrictions from the Crimean Tatars, Balkars, Soviet Turks, Kurds, Hemshils and members of their families deported during the Great Patriotic War" ordered the release of these ethnic groups from the administrative control of the MVD

The Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation (MVD; russian: Министерство внутренних дел (МВД), ''Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del'') is the interior ministry of Russia.

The MVD is responsible for law enfor ...

bodies, but did not envisage their return to their native lands. Unlike other deported peoples, the Meskhetian Turks were not rehabilitated. They were one of three ethnic groups who were not allowed to return to their native lands, the other two being the Volga Germans and the Crimean Tatars.

Official Soviet publications made no mention of either the Meskhetian Turks nor their region of origin between 1945 and 1968. On 30May 1968 a decree of Presidium of the Supreme Soviet acknowledged their deportation, but its text claimed that the Meskhetian Turks "had taken roots" in their new homes of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and called upon them to stay there. The Meskhetian Turks signed 144 petitions in 45 years, demanding a right to return. In 1964 they formed the ''Turkish Association for the National Rights of the Turkish People in Exile'' and tried to contact the U.N.

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

and Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

to help them return. Between 1961 and 1969, there were six attempts to return to Georgia, but these groups were all deported once again. In the 1960s, the Soviet government resorted to repression in order to suppress the Meskhetian Turk movement that demanded a right to return to the Meshekti region. The methods included arrests, intimidation and imprisonment of Meskhetian Turk activists. Moreover, on 26July 1968, Vasil Mzhavanadze

Vasil Pavlovich Mzhavanadze ( ka, ვასილ მჟავანაძე; – 31 August 1988) was a Georgian Soviet politician who served as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Georgian SSR from September 1953 to September 28, ...

, the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Georgian SSR, announced that there was no room for the return of that ethnic group in the area and that only 100 families might return per year. 1,211 Meskhetian Turks returned to Georgia, but were dispersed away from the Meskheti region, to the western part of the country. In June 1988, some 200 representatives of the ethnic group protested in the Borjomi

Borjomi ( ka, ბორჯომი) is a resort town in south-central Georgia, 160 km from Tbilisi, with a population of 11,122 (2021). It is one of the municipalities of the Samtskhe–Javakheti region and is situated in the northwestern p ...

District, demanding a right to return. By 1989, only 35 families remained in Georgia, while the only Meskhetian Turks who returned to the Meskheti region were eventually forced to leave it.

The situation changed, at least on paper, in the late 1980s when the new Soviet leader,

The situation changed, at least on paper, in the late 1980s when the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet politician who served as the 8th and final leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

, decided to break all ties with the Stalinist past. On 14November 1989, the Supreme Soviet

The Supreme Soviet (russian: Верховный Совет, Verkhovny Sovet, Supreme Council) was the common name for the legislative bodies (parliaments) of the Soviet socialist republics (SSR) in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) ...

declared that the forced displacement of ethnic groups during Stalin's era, including the Meskhetian Turks, was "illegal and criminal". On 26April 1991 the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

, under its chairman Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

, passed the law ''On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples ''On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples'' (russian: Закон РСФСР от 26 апреля 1991 г. N 1107-I "О реабилитации репрессированных народов") is the law N 1107-I of the Russian Soviet Federati ...

'' with Article 2 denouncing all mass deportations as "Stalin's policy of defamation and genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

". Even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

in 1991, the newly independent Georgia refused to give Meskhetian Turks the right to return to the Meskheti region. One of the rare exceptions in Georgia was Guram Mamulia

Guram Mamulia ( ka, გურამ მამულია; May 9, 1937 – January 1, 2003) was a Georgian historian, politician and campaigner for Meskhetian rights. A month after Mamulia was born, his father, Samson Mamulia was imprisoned and ...

, a politician, historian and human rights activist who advocated for the Meskhetian Turk right to move back to Meskheti. Unlike the other ethnic groups resettled during Soviet deportations, the Meskhetian Turks were sparsely mentioned in the books covering the subject by historians Alexander Nekrich Aleksandr Moiseyevich Nekrich, 3 March 1920, Baku – 31 August 1993, Boston) was a Soviet Russian historian. He emigrated to the United States in 1976. He is known for his works on the history of the Soviet Union, especially under Joseph Stalin ...

and Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

. Russian historian Pavel Polian

Pavel Markovich Polian, pseudonym: Pavel Nerler (russian: Павел Маркович Полян; born 31 August 1952) is a Russian geographer and historian, and Doctor of Sciences, Doctor of Geographical Sciences with the Institute of Geography ( ...

considered all of the deportations of entire ethnic groups during Stalin's era, including those from the Caucasus, as a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are widespread or systemic acts committed by or on behalf of a ''de facto'' authority, usually a state, that grossly violate human rights. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity do not have to take place within the c ...

. He also noted that the charges of treason were "both unfair and hypocritical" considering that almost 40,000 Meskhetian Turks fought on the Soviet side during World War II.

In June 1989, the Meskhetian Turks were victims of Uzbek nationalist violence in the Fergana valley

The Fergana Valley (; ; ) in Central Asia lies mainly in eastern Uzbekistan, but also extends into southern Kyrgyzstan and northern Tajikistan.

Divided into three republics of the former Soviet Union, the valley is ethnically diverse and in the ...

. Until these events, only few people were aware of the existence of the Meskhetian Turks and very little scholarly research had been conducted about them. After the ethnic clashes in the Fergana valley, 70,000 Meskhetian Turks fled and were scattered across seven countries of the former Soviet Union. The Meskhetian Turks numbered between 260,000 and 335,000 people in 2006. Since Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

officials refused to grant the Meskhetian Turks the status of Russian citizens, the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold European Convention on Human Rights, human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. ...

has described their position in Krasnodar

Krasnodar (; rus, Краснода́р, p=krəsnɐˈdar; ady, Краснодар), formerly Yekaterinodar (until 1920), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Krasnodar Krai, Russia. The city stands on the Kuban River in southern ...

as one of a "legal limbo". A majority of them remain ''de facto'' stateless people.

See also

*Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush

The deportation of the Chechens and Ingush ( ce, До́хадар, Махках дахар, inh, Мехках дахар), or Ardakhar Genocide ( ce, Ардахар Махках), and also known as Operation Lentil (russian: Чечевица ...

* Deportation of the Crimean Tatars

The deportation of the Crimean Tatars ( crh, Qırımtatar halqınıñ sürgünligi, Cyrillic: Къырымтатар халкъынынъ сюргюнлиги) or the Sürgünlik ('exile') was the ethnic cleansing and cultural genocide of at ...

* Deportation of the Karachays

The Deportation of the Karachays (), codenamed Operation Seagull, was the forced transfer by the Soviet government of the entire Karachay population of the North Caucasus to Central Asia, mostly the Kazakh and Kyrgyzstan SSR, in November 1943, ...

*Deportation of the Kalmyks

The Kalmyk deportations of 1943, codename Operation Ulusy () was the Soviet deportation of more than 93,000 people of Kalmyk nationality, and non-Kalmyk women with Kalmyk husbands, on 28–31 December 1943. Families and individuals were forci ...

* Deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union

The deportation of Koreans in the Soviet Union (; ) was the forced transfer of nearly 172,000 Soviet Koreans (Koryo-saram) from the Russian Far East to unpopulated areas of the Kazakh SSR and the Uzbek SSR in 1937 by the NKVD on the orders of S ...

* Human rights in the Soviet Union

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, an ...

* Political repression in the Soviet Union

Throughout the history of the Soviet Union, tens of millions of people suffered political repression, which was an instrument of the state since the October Revolution. It culminated during the Stalin era, then declined, but it continued to exist ...

* Population transfer in the Soviet Union

From 1930 to 1952, the government of the Soviet Union, on the orders of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin under the direction of the NKVD official Lavrentiy Beria, forcibly transferred populations of various groups. These actions may be classified ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{refendExternal links

Meskhetians or Meskhetian Turks - Minority Rights Group

1944 in the Soviet Union Ethnic cleansing in Europe

Meskhetian Turks

Meskhetian Turks, also referred to as Turkish Meskhetians, Ahiska Turks, and Turkish Ahiskans, ( ka, მესხეთის თურქები ''Meskhetis turk'ebi'') are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti regio ...

Political repression in the Soviet Union

Russian special forces operations

Soviet World War II crimes

Crimes against humanity

1940s in Georgia (country)

Persecution of Turkish people