Japan was

occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

and administered by the victorious

Allies of World War II

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy. ...

from the 1945

surrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

of the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent fo ...

at the end of the war until the

Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

took effect in 1952. The occupation, led by the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

with

support

Support may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Supporting character

Business and finance

* Support (technical analysis)

* Child support

* Customer support

* Income Support

Construction

* Support (structure), or lateral support, a ...

from the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

and under the supervision of the

Far Eastern Commission

The Far Eastern Commission (FEC) was an Allied commission which succeeded the Far Eastern Advisory Commission (FEAC), and oversaw the Allied Council for Japan following the end of World War II. Based in Washington, D.C., it was first agreed on at ...

, involved a total of nearly 1 million

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

soldiers. The occupation was overseen by American

General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

, who was appointed

Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

by US President

Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

; MacArthur was succeeded as supreme commander by General

Matthew Ridgway

General Matthew Bunker Ridgway (March 3, 1895 – July 26, 1993) was a senior officer in the United States Army, who served as Supreme Allied Commander Europe (1952–1953) and the 19th Chief of Staff of the United States Army (1953–1955). Altho ...

in 1951. Unlike in the

occupation of Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

had little to no influence over the occupation of Japan, declining to participate because it did not want to place Soviet troops under MacArthur's direct command.

This foreign presence marks the only time in Japan's history that it has been occupied by a foreign power. However, unlike in Germany the Allies never assumed direct control over Japan's civil administration. In the immediate aftermath of Japan's military surrender, the country's government continued to formally operate under the provisions of the

Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in for ...

. Furthermore, at MacArthur's insistence, Emperor

Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

remained on the imperial throne and was effectively granted full immunity from prosecution for war crimes after he agreed to replace the wartime cabinet with a ministry acceptable to the Allies and committed to implementing the terms of the

Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

, which among other things called for the country to become a

parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

. Under MacArthur's guidance, the Japanese government introduced sweeping social reforms and implemented economic reforms that recalled American "

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

" priorities of the 1930s under President

Roosevelt

Roosevelt may refer to:

*Theodore Roosevelt (1858–1919), 26th U.S. president

* Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882–1945), 32nd U.S. president

Businesses and organisations

* Roosevelt Hotel (disambiguation)

* Roosevelt & Son, a merchant bank

* Rooseve ...

. In 1947, a sweeping amendment to the Meiji Constitution was passed which effectively repealed it in its entirety and replaced it with a new,

American-written constitution, and the emperor's theoretically vast powers, which for many centuries had been constrained only by conventions that had evolved over time, became strictly limited by law.

Article 9 of the constitution explicitly forbade Japan from maintaining a military or pursuing war as a means to settle international disputes.

The occupation officially ended with coming into force of the

San Francisco Peace Treaty

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

, signed on September 8, 1951, and

effective from April 28, 1952, after which the U.S. military ceased any direct involvement in the country's civil administration thus effectively restoring full sovereignty to Japan with the

exception of the

Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

. The simultaneous implementation of the

U.S.-Japan Security Treaty

The , more commonly known as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in English and as the or just in Japanese, is a treaty that permits the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, and commits the two nations to defend each other if one or th ...

allowed tens of thousands of American soldiers to remain based in Japan indefinitely, albeit at the invitation of the Japanese government and not as an occupation force.

The occupation of Japan can be usefully divided into three phases: the initial effort to punish and reform Japan; the so-called "

Reverse Course

The is the name commonly given to a shift in the policies of the U.S. government and the U.S.-led Allied occupation of Japan as they sought to reform and rebuild Japan after World War II. The Reverse Course began in 1947, at a time of rising Co ...

" in which the focus shifted to suppressing dissent and reviving the Japanese economy to support the U.S. in the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

; and the final establishment of a

formal peace treaty and

enduring military alliance.

["Occupation and Reconstruction of Japan, 1945–52"]

/ref>

Background

Initial planning

American planning for a post-war occupation of Japan began as early as February 1942, when President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

established an Advisory Committee on Postwar Foreign Policy to advise him on the postwar reconstruction of Germany, Italy, and Japan. On matters related to Japan, this committee was later succeeded by the smaller Inter-Departmental Area Committee on the Far East (IDAFE), which met 234 times between fall 1942 and summer 1945 and had frequent discussions with the President.

During the war, the Allied Powers had planned to divide Japan amongst themselves for the purposes of occupation, as was done for the occupation of Germany

Germany was already de facto occupied by the Allies from the real fall of Nazi Germany in World War II on 8 May 1945 to the establishment of the East Germany on 7 October 1949. The Allies (United States, United Kingdom, Soviet Union, and Franc ...

. Under the final plan, however, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

(SCAP) was to be given direct control over the main islands of Japan (Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separ ...

, Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

, Shikoku

is the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. It is long and between wide. It has a population of 3.8 million (, 3.1%). It is south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. Shikoku's ancient names include ''Iyo-no-futana-shima'' (), '' ...

, and Kyushu

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surroun ...

) and the immediately surrounding islands, while outlying possessions were divided between the Allied Powers as follows:

* Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

: Northern Korea

North Korea is located in East Asia in the Northern half of Korea, partially on the Korean Peninsula. It borders three countries: China along the Yalu (Amnok) River, Russia along the Tumen River, and South Korea to the south.

Topography and dr ...

, South Sakhalin

Karafuto Prefecture ( ja, 樺太庁, ''Karafuto-chō''; russian: Префектура Карафуто, Prefektura Karafuto), commonly known as South Sakhalin, was a prefecture of Japan located in Sakhalin from 1907 to 1949.

Karafuto became ter ...

, and the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

* United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

: Southern Korea, Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

, the Amami Islands

The The name ''Amami-guntō'' was standardized on February 15, 2010. Prior to that, another name, ''Amami shotō'' (奄美諸島), was also used. is an archipelago in the Satsunan Islands, which is part of the Ryukyu Islands, and is southwest o ...

, the Ogasawara Islands

The Bonin Islands, also known as the , are an archipelago of over 30 subtropical and tropical islands, some directly south of Tokyo, Japan and northwest of Guam. The name "Bonin Islands" comes from the Japanese word ''bunin'' (an archaic readi ...

and Japanese possessions in Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

* China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

: Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

and Penghu

The Penghu (, Hokkien POJ: ''Phîⁿ-ô͘'' or ''Phêⁿ-ô͘'' ) or Pescadores Islands are an archipelago of 90 islands and islets in the Taiwan Strait, located approximately west from the main island of Taiwan, covering an area ...

In early August 1945, with Japan's surrender seeming probable, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

recommended to President Truman that Pacific Theatre Commander General Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

be named Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

was the title held by General Douglas MacArthur during the United States-led Allied occupation of Japan following World War II. It issued SCAP Directives (alias SCAPIN, SCAP Index Number) to the Japanese government, aiming to suppress its "milit ...

(SCAP) to oversee the surrender and occupation of Japan. Truman agreed, and MacArthur asked his staff in Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

to begin making concrete preparations for the occupation of Japan.

In a bid to occupy as much Japanese territory as possible, Soviet troops continued offensive military operations even after the Japanese surrender, causing large-scale civilian casualties. Such operations included final battles on the Kuril Islands and South Sakhalin well past the end of August in 1945. In the end, despite its initial hopes, the Soviet Union did not manage to occupy any part of the Japanese home islands, largely due to significant US opposition which was backed by the leverage gained by its then-newly-realized status as the world's only nuclear-armed state.

In any case, Stalin was not inclined to press the Americans very far following Japan's surrender. He was not willing to place Soviet troops under MacArthur's direct command. Furthermore, in terms of both strategic interests and prestige the Soviets had achieved most of their war aims in the Far East. Moreover, whereas China, Korea and Japan were all a considerable distance from the USSR's European heartland, Stalin regarded establishing a powerful buffer against further military threats from the west to be vital to the Soviet Union's future existence. He therefore placed a far greater priority on establishing Soviet communist influence in Europe rather than in Asia.

Japanese surrender and initial landings

Following the dropping of atomic bombs and the entry of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

into the war against Japan, on the night of 9-10 August 1945, Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

announced his decision to accept the terms demanded by the Allies in the Potsdam Declaration

The Potsdam Declaration, or the Proclamation Defining Terms for Japanese Surrender, was a statement that called for the surrender of all Japanese armed forces during World War II. On July 26, 1945, United States President Harry S. Truman, Uni ...

. On August 15, 1945; Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's unconditional surrender to the Japanese people in a nationwide radio broadcast.

Japanese officials left for Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populate ...

on August 19 to meet MacArthur and to discuss surrender terms. On August 28, 1945, a week before the official surrender ceremony, one hundred fifty US personnel flew to Atsugi

is a city located in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 223,960 and a population density of 2400 persons per km². The total area of the city is .

While the name "Atsugi" is often associated with the United ...

, Kanagawa Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Kanagawa Prefecture is the second-most populous prefecture of Japan at 9,221,129 (1 April 2022) and third-densest at . Its geographic area of makes it fifth-smallest. Kana ...

. They were followed by the USS ''Missouri'', whose accompanying vessels landed the 4th Marine Regiment

The 4th Marine Regiment is an infantry regiment of the United States Marine Corps. Based at Camp Schwab in Okinawa, Japan, it is part of the 3rd Marine Division of the III Marine Expeditionary Force.

Mission

Close with and destroy the enemy by fi ...

on the southern coast of Kanagawa. The 11th Airborne Division

The 11th Airborne Division ("Arctic Angels") is a United States Army airborne formation, first activated on 25 February 1943, during World War II. Consisting of one parachute and two glider infantry regiments, with supporting troops, the div ...

was airlifted from Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

to Atsugi Airdrome, from Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

. Other Allied personnel followed.

MacArthur arrived in Tokyo on August 30 and immediately decreed several laws. No Allied personnel were to assault Japanese people or eat the scarce Japanese food. Flying the ''Hinomaru

The national flag of Japan is a rectangular white banner bearing a crimson-red circle at its center. This flag is officially called the , but is more commonly known in Japan as the . It embodies the country's sobriquet: the Land of the Rising S ...

'' (sun disc) flag was initially severely restricted (although individuals and prefectural offices could apply for permission to fly it); this restriction was partially lifted in 1948 and completely lifted the following year.Japanese Instrument of Surrender

The Japanese Instrument of Surrender was the written agreement that formalized the surrender of the Empire of Japan, marking the end of hostilities in World War II. It was signed by representatives from the Empire of Japan and from the Allied nat ...

. On September 6, US President Truman approved a document titled "US Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan The US Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan is a legal document approved by US President Harry S. Truman on September 6, 1945, which governed US policy in the occupation of Japan following surrender in the Second World War. It was released to th ...

". The document set two main objectives for the occupation: eliminating Japan's war potential and turning Japan into a democratic nation with pro-United Nations orientation.

Size and scope

By the end of 1945, around 430,000 American soldiers were stationed throughout Japan. Of the main Japanese islands,

By the end of 1945, around 430,000 American soldiers were stationed throughout Japan. Of the main Japanese islands, Kyūshū

is the third-largest island of Japan's five main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands ( i.e. excluding Okinawa). In the past, it has been known as , and . The historical regional name referred to Kyushu and its surround ...

was occupied by the 24th Infantry Division, with some responsibility for Shikoku

is the smallest of the four main islands of Japan. It is long and between wide. It has a population of 3.8 million (, 3.1%). It is south of Honshu and northeast of Kyushu. Shikoku's ancient names include ''Iyo-no-futana-shima'' (), '' ...

. Honshu

, historically called , is the largest and most populous island of Japan. It is located south of Hokkaidō across the Tsugaru Strait, north of Shikoku across the Inland Sea, and northeast of Kyūshū across the Kanmon Straits. The island separ ...

was occupied by the First Cavalry Division and Sixth Army. Hokkaido

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

was occupied by the 11th Airborne Division. By the beginning of 1946, replacement troops began to arrive in the country in large numbers and were assigned to MacArthur's Eighth Army, headquartered in Tokyo's Dai-Ichi

(第一) is a compound modifier phrase of Japanese origin, meaning '' number one'', or ''first''. In kanji, "dai" ("number") is 第Nakao, Seigo''Random House Japanese-English English-Japanese Dictionary'' via Google Books, p. 39. Retrieved 2011- ...

building. In total, including rotations of replacement troops throughout the seven years, nearly 1 million American soldiers would serve in the Occupation, in addition to thousands of civilian contractors and tens of thousands of dependents.

The American forces were supplemented by around 40,000 troops from the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

. The official British Commonwealth Occupation Force

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) was the British Commonwealth taskforce consisting of Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand military forces in occupied Japan, from 1946 until the end of occupation in 1952.

At its peak, t ...

(BCOF), composed of Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Au ...

, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

, Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

personnel, did not begin deployment to Japan until February 21, 1946. While US forces were responsible for the overall occupation, BCOF was responsible for supervising demilitarization and the disposal of Japan's war industries. BCOF was also responsible for occupation of several western prefectures and had its headquarters at Kure

is a port and major shipbuilding city situated on the Seto Inland Sea in Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan. With a strong industrial and naval heritage, Kure hosts the second-oldest naval dockyard in Japan and remains an important base for the Japan M ...

. At its peak, the force numbered about 40,000 personnel. During 1947, BCOF began to decrease its activities in Japan, and officially wound up in 1951.

The Far Eastern Commission

The Far Eastern Commission (FEC) was an Allied commission which succeeded the Far Eastern Advisory Commission (FEAC), and oversaw the Allied Council for Japan following the end of World War II. Based in Washington, D.C., it was first agreed on at ...

and Allied Council for Japan were also established to supervise the occupation of Japan. The establishment of a multilateral Allied council for Japan was proposed by the Soviet government as early as September 1945, and was supported partially by the British, French and Chinese governments.

Initial phase

The initial phase of the Occupation focused on punishing Japan for having made war on the Allies, and undertook a thorough reformation of Japanese society to ensure that Japan would never again be a threat to world peace. Reforms targeted all major sectors of Japanese society, government, and economy. Historians have emphasized similarities to the American New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

programs of the 1930s. Moore and Robinson note that, "New Deal liberalism seemed natural, even to conservative Republicans such as MacArthur and Whitney Whitney may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Whitney'' (2015 film), a Whitney Houston biopic starring Yaya DaCosta

* ''Whitney'' (2018 film), a documentary about Whitney Houston

* ''Whitney'' (TV series), an American sitcom that premiered i ...

."

Feeding the starving populace

Before reforms could be undertaken, MacArthur's first priority was to set up a food distribution network. Following the collapse of the ruling government and the wholesale destruction of most major cities, virtually the entire Japanese populace was starving. The air raids on Japan's urban centers left millions displaced, and food shortages (created by bad harvests and the demands of the war) worsened when the seizure of foodstuffs from Korea, Taiwan, and China ceased. Repatriation of Japanese people living in other parts of Asia and hundreds of thousands of demobilized prisoners of war only aggravated the hunger problem in Japan, as these people put more strain on already scarce resources. Around 5.1 million Japanese returned to Japan in the fifteen months following October 1, 1945, and another million returned in 1947. As expressed by Kazuo Kawai, "Democracy cannot be taught to a starving people". Initially, the US government provided emergency food relief through Government Aid and Relief in Occupied Areas (

Before reforms could be undertaken, MacArthur's first priority was to set up a food distribution network. Following the collapse of the ruling government and the wholesale destruction of most major cities, virtually the entire Japanese populace was starving. The air raids on Japan's urban centers left millions displaced, and food shortages (created by bad harvests and the demands of the war) worsened when the seizure of foodstuffs from Korea, Taiwan, and China ceased. Repatriation of Japanese people living in other parts of Asia and hundreds of thousands of demobilized prisoners of war only aggravated the hunger problem in Japan, as these people put more strain on already scarce resources. Around 5.1 million Japanese returned to Japan in the fifteen months following October 1, 1945, and another million returned in 1947. As expressed by Kazuo Kawai, "Democracy cannot be taught to a starving people". Initially, the US government provided emergency food relief through Government Aid and Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA Government Aid and Relief in Occupied Areas (GARIOA) was a program under which the United States after the 1945 end of World War II from 1946 onwards provided emergency aid to the occupied nations of Japan, Germany, and Austria. The aid was predomi ...

) funds. In fiscal year 1946, this aid amounted to US$92 million in loans. From April 1946, under the guise of Licensed Agencies for Relief in Asia

A license (or licence) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another party (licensee) as an element of an agreeme ...

, private relief organizations were also permitted to provide relief. Even with these measures, millions of people were still on the brink of starvation for several years after the surrender.

Preserving the emperor

Once the food network was in place, MacArthur set out to win the support of Hirohito. The two men met for the first time on September 27; the photograph of the two together is one of the most famous in Japanese history. Some were shocked that MacArthur wore his standard duty uniform with no tie, instead of his dress uniform, when meeting the emperor. The difference in height between the towering MacArthur and the diminutive Hirohito also impressed upon Japanese citizens who was in charge now. With the cooperation of Japan's reigning monarch, MacArthur had the political ammunition he needed to begin the real work of the occupation. While other Allied political and military leaders pushed for Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal, MacArthur resisted such calls, arguing that any such prosecution would be overwhelmingly unpopular with the Japanese people. He also rejected calls for

Once the food network was in place, MacArthur set out to win the support of Hirohito. The two men met for the first time on September 27; the photograph of the two together is one of the most famous in Japanese history. Some were shocked that MacArthur wore his standard duty uniform with no tie, instead of his dress uniform, when meeting the emperor. The difference in height between the towering MacArthur and the diminutive Hirohito also impressed upon Japanese citizens who was in charge now. With the cooperation of Japan's reigning monarch, MacArthur had the political ammunition he needed to begin the real work of the occupation. While other Allied political and military leaders pushed for Hirohito to be tried as a war criminal, MacArthur resisted such calls, arguing that any such prosecution would be overwhelmingly unpopular with the Japanese people. He also rejected calls for abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

, promoted by some members of the imperial family such as Prince Mikasa

was a Japanese prince, the youngest of the four sons of Emperor Taishō (Yoshihito) and Empress Teimei (Sadako). He was their last surviving child. His eldest brother was Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito). After serving as a junior cavalry officer in ...

and Prince Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince H ...

and demands of intellectuals like Tatsuji Miyoshi

was a Japanese poet, literary critic, and literary editor active during the Shōwa period of Japan. He is known for his lengthy free verse poetry, which often portray loneliness and isolation as part of contemporary life, but which are written ...

.

Disarmament and demobilization

Japanese soldiers were rapidly disarmed and demobilized en masse. On September 15, 1945, the Japanese Imperial Headquarters was dissolved. By December, all Japanese military forces in the Japanese home islands were fully disbanded. Occupation forces also exploded or dumped into the sea over 2 million tons of unused munitions and other war materiel.

Release of political prisoners

The issuing of the Removal of Restrictions on Political, Civil, and Religious Liberties directive by SCAP on October 4, 1945, led to the abolition of the

The issuing of the Removal of Restrictions on Political, Civil, and Religious Liberties directive by SCAP on October 4, 1945, led to the abolition of the Peace Preservation Law

The was a Japanese law enacted on April 22, 1925, with the aim of allowing the Special Higher Police to more effectively suppress socialists and communists. In addition to criminalizing forming an association with the aim of altering the ''kokuta ...

and the release of all political prisoners.Japan Communist Party

The is a left-wing to far-left political party in Japan. With approximately 270,000 members belonging to 18,000 branches, it is one of the largest non-governing communist parties in the world.

The party advocates the establishment of a democra ...

was granted legal status.

Disestablishment of State Shinto

On December 15, 1945, the Shinto Directive

The Shinto Directive was an order issued in 1945 to the Japanese government by Occupation authorities to abolish state support for the Shinto religion. This unofficial "State Shinto" was thought by Allies to have been a major contributor to J ...

was issued, abolishing Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

as a state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

and prohibiting some of its teachings and rites that were deemed to be militaristic or ultra-nationalistic.

Trade Union Act

On December 22, 1945, at SCAP's direction, the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

passed Japan's first ever trade union law protecting the rights of workers to form or join a union, to organize, and take industrial action. There had been pre-war attempts to do so, but none that were successfully passed until the Allied occupation. A new Trade Union Law was passed on June 1, 1949, which remains in place to the present day. According to Article 1 of the Act, the purpose of the act is to "elevate the status of workers by promoting their being on equal standing with the employer".

Purge of wartime public officials

In January 1946, SCAP issued directives calling for the purge of wartime officials from public offices. Individuals targeted in the purge included accused war criminals, military officers, leaders of ultranationalist societies, leaders in the Imperial Rule Assistance Association

The , or Imperial Aid Association, was the Empire of Japan's ruling organization during much of World War II. It was created by Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe on 12 October 1940, to promote the goals of his ("New Order") movement. It evolved ...

, business leaders involved in Japanese overseas economic expansion, governors of former Japanese colonies, and national leaders involved in the decisions leading Japan into war. Ultimately, SCAP screened a total of 717,415 possible purgees, and wound up excluding 201,815 of them from holding public office. However, as part of the "Reverse Course

The is the name commonly given to a shift in the policies of the U.S. government and the U.S.-led Allied occupation of Japan as they sought to reform and rebuild Japan after World War II. The Reverse Course began in 1947, at a time of rising Co ...

" in Occupation policy, most of the purgees would be de-purged and allowed to return to public life by 1951.

Enfranchisement of women

In September 1945, at SCAP's urging, the Japanese government agreed to lower the voting age and extend the voting franchise to women in future elections. On April 10, 1946, an election with 78.52% voter turnout among men and 66.97% among women was held, giving Japan its first prime minister partially elected by women, Shigeru Yoshida

(22 September 1878 – 20 October 1967) was a Japanese diplomat and politician who served as prime minister of Japan from 1946 to 1947 and from 1948 to 1954. Yoshida was one of the longest-serving Japanese prime ministers, and is the third-long ...

.

Hirohito renounces his divinity

At SCAP's insistence, as part of a New Year's Day message, Emperor Hirohito publicly renounced his own divinity, declaring:

New constitution

In 1947, the Diet ratified a new Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan (Shinjitai: , Kyūjitai: , Hepburn: ) is the constitution of Japan and the supreme law in the state. Written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japan, the constitution r ...

that followed closely a "model copy" drafted by American civilian officials within SCAP, and was promulgated to replace the old Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

n-style Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in for ...

that had granted the Emperor theoretically unlimited powers. The new constitution drew inspiration from the U.S. Bill of Rights

The United States Bill of Rights comprises the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. Proposed following the often bitter 1787–88 debate over the ratification of the Constitution and written to address the objections rais ...

, New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

social legislation, the liberal constitution

Constitutional liberalism is a form of government that upholds the principles of classical liberalism and the rule of law. It differs from liberal democracy in that it is not about the method of selecting government.

The journalist and scholar ...

s of several European states and even the Soviet Union, and transferred sovereignty from the Emperor to the people in an attempt to depoliticize the Throne and reduce it to the status of a state symbol. Included in the revised charter was the famous Article Nine, whereby Japan forever renounced war as an instrument of state policy and became forbidden to maintain a standing army. The 1947 Constitution also officially enfranchised women, guaranteed fundamental human rights, strengthened the powers of Parliament and the Cabinet, and decentralized the police and local government.

Zaibatsu dissolution

To further remove Japan as a potential future threat to the United States, the Far Eastern Commission

The Far Eastern Commission (FEC) was an Allied commission which succeeded the Far Eastern Advisory Commission (FEAC), and oversaw the Allied Council for Japan following the end of World War II. Based in Washington, D.C., it was first agreed on at ...

decided that Japan was to be partly de-industrialized. In the end, SCAP adopted a program of de-industrialization and de-concentration in Japan that was implemented to a lesser degree than the similar U.S. "industrial disarmament" program in Germany.[Frederick H. Gareau "Morgenthau's Plan for Industrial Disarmament in Germany" The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Jun., 1961), pp. 531.] To this end, the prewar ''zaibatsu

is a Japanese language, Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertical integration, vertically integrated business conglomerate (company), conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over signi ...

'' industrial conglomerates were pressured into undergoing "voluntary" dissolution into smaller independent companies. Although SCAP originally planned to break up 325 Japanese companies, as a result of changes in priorities in connection with the "Reverse Course

The is the name commonly given to a shift in the policies of the U.S. government and the U.S.-led Allied occupation of Japan as they sought to reform and rebuild Japan after World War II. The Reverse Course began in 1947, at a time of rising Co ...

," in the end only the 11 largest companies were dissolved.

Labor Standards Act

The Labor Standards Act was enacted on April 7, 1947, to govern working conditions in Japan. According to Article 1 of the Act, its goal is to ensure that "Working conditions shall be those which should meet the needs of workers who live lives worthy of human beings." Support stemming from the Allied occupation has introduced better working conditions and pay for numerous employees in Japanese business.Thought Police

In the dystopian novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (1949), by George Orwell, the Thought Police (''Thinkpol'') are the secret police of the superstate of Oceania, who discover and punish ''thoughtcrime'', personal and political thoughts unapproved ...

, who had become the head of the Labor Standards section of the Welfare Ministry.

Education reform

Before and during the war, Japanese education was based on the German system, with " Gymnasien" (selective grammar schools) and universities to train students after primary school. During the occupation, Japan's secondary education system was changed to incorporate three-year junior high schools and senior high schools similar to those in the US: junior high school became compulsory but senior high school remained optional. The Imperial Rescript on Education

The , or IRE for short, was signed by Emperor Meiji of Japan on 30 October 1890 to articulate government policy on the guiding principles of education on the Empire of Japan. The 315 character document was read aloud at all important school events, ...

was repealed, and the Imperial University system reorganized. The longstanding issue of Japanese script reform

The Japanese script reform is the attempt to correlate standard spoken Japanese with the written word, which began during the Meiji period. This issue is known in Japan as the . The reforms led to the development of the modern Japanese written ...

, which had been planned for decades but continuously opposed by more conservative elements, was also resolved during this time. The Japanese writing system

The modern Japanese writing system uses a combination of logographic kanji, which are adopted Chinese characters, and syllabic kana. Kana itself consists of a pair of syllabaries: hiragana, used primarily for native or naturalised Japanese wo ...

was drastically reorganized with the Tōyō kanji

Toyo may refer to:

Places

*Tōyō, Kōchi, a town in Japan

*Tōyo, Ehime, a former city in Japan

*Toyo Province, a Japanese province divided in 683

*Tōyō, Kumamoto, a village located in Yatsuhiro District, Kumamoto, Japan

* Tōyō, Tokyo, a ...

-list in 1946, predecessor of today's Jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

, and orthography was greatly altered to reflect spoken usage.

Land reform

A sweeping land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

was also conducted, led by Wolf Ladejinsky

Wolf Isaac Ladejinsky (March 15, 1899 – July 3, 1975) was an American Georgist agricultural economist and researcher, serving first in the United States Department of Agriculture, then the Ford Foundation and later the World Bank. He was a key ...

from SCAP. However, Ladejinsky would claim that the real architect of the reform was , former Japanese Minister of Agriculture and Forestry. Between 1947 and 1949, approximately of land (approximately 38% of Japan's cultivated land) were purchased from the landlord

A landlord is the owner of a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate which is rented or leased to an individual or business, who is called a tenant (also a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). When a juristic person is in this position, the ...

s under the government's reform program and resold at extremely low prices (after inflation) to the farmers who worked them. MacArthur's land reform redistribution resulted in only 10% of the land being worked by non-owners.

Punishing war criminals

While these other reforms were taking place, various military tribunals, most notably the

While these other reforms were taking place, various military tribunals, most notably the International Military Tribunal for the Far East

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conven ...

in Ichigaya

is an area in the eastern portion of Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan.

Places in Ichigaya

*Hosei University Ichigaya Campus

*Chuo University Graduate School

*Ministry of Defense headquarters: Formerly GHQ of the Imperial Japanese Army; following World W ...

, were trying Japan's war criminals and sentencing many to death and imprisonment. However, many suspects such as Masanobu Tsuji

was a Japanese army officer and politician. During World War II, he was an important tactical planner in the Imperial Japanese Army and developed the detailed plans for the successful Japanese invasion of Malaya at the start of the war. He als ...

, Nobusuke Kishi

was a Japanese bureaucrat and politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960.

Known for his exploitative rule of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in Northeast China in the 1930s, Kishi was nicknamed the "Monster of the Shō ...

, Yoshio Kodama

was a Japanese right-wing ultranationalist and a prominent figure in the rise of organized crime in Japan. The most famous '' kuromaku'', or behind-the-scenes power broker, of the 20th century, he was active in Japan's political arena and crimi ...

and Ryōichi Sasakawa

was a Japanese suspected war criminal, businessman, far-right politician, and philanthropist. He was born in Minoh, Osaka. In the 1930s and during the Second World War he was active both in finance and in politics, actively supporting the Japane ...

were never judged, while the Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

, all members of the imperial family implicated in the war such as Prince Chichibu

, was the second son of Emperor Taishō (Yoshihito) and Empress Teimei (Sadako), a younger brother of Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) and a general in the Imperial Japanese Army. As a member of the Imperial House of Japan, he was the patron of several ...

, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, Prince Fushimi Hiroyasu

was a scion of the Japanese imperial family and was a career naval officer who served as chief of staff of the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1932 to 1941.

Early life

Prince Hiroyasu was born in Tokyo as Prince Narukata, the eldest son of Prin ...

, Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni

General was a Japanese imperial prince, a career officer in the Imperial Japanese Army and the 30th Prime Minister of Japan from 17 August 1945 to 9 October 1945, a period of 54 days. An uncle-in-law of Emperor Hirohito twice over, Prince H ...

and Prince Tsuneyoshi Takeda

was the second and last heir of the Takeda-no-miya collateral branch of the Japanese Imperial Family.

Biography Early life

Prince Takeda Tsuneyoshi was the only son of Prince Takeda Tsunehisa and Masako, Princess Tsune (1888–1940), the ...

, and all members of Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in lethal human experimentatio ...

—including its director Dr. Shirō Ishii

Surgeon General was a Japanese microbiologist and army medical officer who served as the director of Unit 731, a biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Ishii led the development and application of biological weapons at Unit 73 ...

—were granted immunity from criminal prosecution by General MacArthur.

Before the war crimes trials actually convened, the SCAP, its International Prosecution Section (IPS) and Shōwa officials worked behind the scenes not only to prevent the imperial family from being indicted, but also to slant the testimony of the defendants to ensure that no one implicated the Emperor. High officials in court circles and the Shōwa government collaborated with Allied GHQ in compiling lists of prospective war criminals, while the individuals arrested as ''Class A'' suspects and incarcerated in Sugamo prison solemnly vowed to protect their sovereign against any possible taint of war responsibility. Thus, months before the Tokyo tribunal

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial or the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on April 29, 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for crimes against peace, conve ...

commenced, MacArthur's highest subordinates were working to attribute ultimate responsibility for Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

to Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

by allowing "the major criminal suspects to coordinate their stories so that the Emperor would be spared from indictment." According to historian John W. Dower

John W. Dower (born June 21, 1938 in Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, Rhode Island) is an American author and historian. His 1999 book ''Embracing Defeat, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II'' won the U.S. National Book Awar ...

, "With the full support of MacArthur's headquarters, the prosecution functioned, in effect, as a defense team for the emperor."

In Dower's view, "Even Japanese peace activists who endorse the ideals of the Nuremberg and Tokyo charters, and who have labored to document and publicize Japanese atrocities, cannot defend the American decision to exonerate the emperor of war responsibility and then, in the chill of Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, release and soon afterwards openly embrace accused right-wing war criminals like the later prime minister Kishi Nobusuke."

The "Reverse Course"

The is the name commonly given to a major shift in the Occupation policies that began in 1947 in response to the emerging global Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. In particular, U.S. priorities shifted from punishing and reforming Japan to ensuring internal political stability, rebuilding the shattered economy, and remilitarizing Japan to the extent possible under Article 9, in support of U.S. Cold War objectives in East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

. This involved relaxing and in some cases even partially undoing earlier reforms the Occupation had enacted in 1945 and 1946. As a U.S. Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

official history puts it, "this 'Reverse Course'...focused on strengthening, not punishing, what would become a key Cold War ally."

An early sign of the shift in SCAP's thinking came in January 1947 when MacArthur announced that he would not permit a massive, nationwide general strike that labor unions had scheduled for February 1. Thereafter, the broader shift in Occupation policies became more and more apparent. Thousands of conservative and nationalist wartime leaders were de-purged and allowed to reenter politics and government ministries. In the industrial sector, plans for further anti-trust actions against the remains of the old ''zaibatsu

is a Japanese language, Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertical integration, vertically integrated business conglomerate (company), conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over signi ...

'' industrial conglomerates were scrapped, and some earlier anti-trust policies were partially undone. The incomplete suppression of the ''zaibatsu'' allowed them to partially reform as "informal associations" known as ''keiretsu

A is a set of companies with interlocking business relationships and shareholdings. In the legal sense, it is a type of informal business group that are loosely organized alliances within the social world of Japan's business community. The ''ke ...

.'' SCAP also attempted to weaken the labor unions they had recently empowered, most notably issuing an edict stripping public-sector workers of their right to go on strike.

In order to stabilize the Japanese economy as soon as possible, American banker

In order to stabilize the Japanese economy as soon as possible, American banker Joseph Dodge

Joseph Morrell Dodge (November 18, 1890 – December 2, 1964) was a chairman of the Detroit Bank, now Comerica. He later served as an economic adviser for postwar economic stabilization programs in Germany and Japan, headed the American delegation ...

was brought in as an economic consultant. Dodge implemented the "Dodge Line

The Dodge Line or Dodge Plan was a financial and monetary contraction policy drafted by American economist Joseph Dodge for Japan to gain economic independence and stamp out inflation after World War II. It was announced on March 7, 1949. The Dod ...

" in 1949, a set of draconian contractionary fiscal and monetary policies that caused much hardship for the Japanese populace but succeeded in getting rampant inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

under control. Dodge also fixed the exchange rate at 360 yen to the dollar, a favorable rate which would help boost Japanese exports in the years to come and power the Japanese economic miracle

The Japanese economic miracle refers to Japan's record period of economic growth between the post-World War II era and the end of the Cold War. During the economic boom, Japan rapidly became the world's second-largest economy (after the Unit ...

.

As part of the Reverse Course, the United States also began pressuring Japan to remilitarize. In 1950, SCAP established the National Police Reserve

The , or NPR, was a lightly armed national police force established in August 1950 during the Allied occupation of Japan. In October 1952, it was expanded to 110,000 men and renamed as the . On July 1, 1954, it was reorganized as the Japan Groun ...

(NPR), which would later become the basis of the present-day Japan Self Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, t ...

(JSDF)

The climax of the Reverse course came in the so-called "Red Purge

The Red Purge (Japanese: レッドパージ; ''reddo pāji'') was an anticommunist movement in occupied Japan from the late 1940s to the early 1950s.: "From 1947, the Japanese government, supported by MacArthur, unleashed a Red Purge that targeted ...

" (''reddo pāji'') of 1950. The "fall

Autumn, also known as fall in American English and Canadian English, is one of the four temperate seasons on Earth. Outside the tropics, autumn marks the transition from summer to winter, in September (Northern Hemisphere) or March ( Southe ...

" of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

to the communists in 1949 and the outbreak of the Korean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

in 1950 had heightened conservative fears that communism was on the march in East Asia. Against this backdrop, the Japanese government and business leaders, with the connivance and encouragement of SCAP, purged tens of thousands of communists, alleged communists, and other leftists from government posts, private sector jobs, and teaching positions at schools and universities.

The Reverse Course significantly weakened left-wing forces and strengthened conservatives, laying the foundations for decades of conservative rule. At the same time, it did not completely destroy leftist forces that had been deliberately unleashed in the Occupation's early stages, setting the stage for extremely contentious political struggles and labor strife in the 1950s, culminating in the massive Anpo protests and Miike Coal Mine Strike, both in 1960.

Ending the occupation

In 1949, MacArthur made a sweeping change in the SCAP power structure that greatly increased the power of Japan's native rulers, and the Occupation began to draw to a close. The

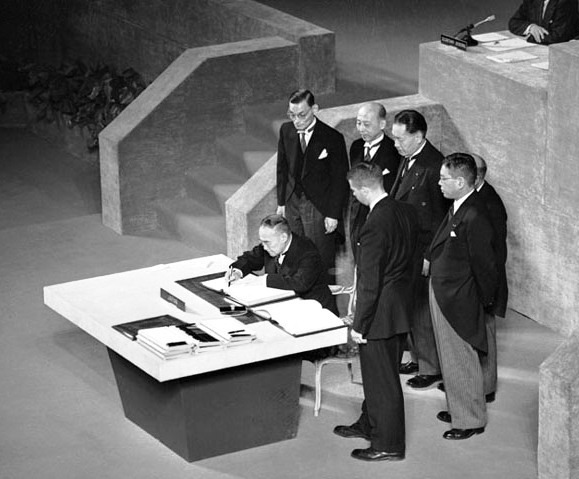

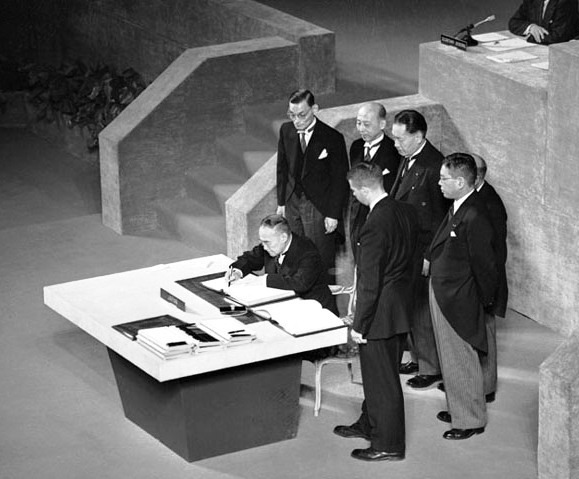

In 1949, MacArthur made a sweeping change in the SCAP power structure that greatly increased the power of Japan's native rulers, and the Occupation began to draw to a close. The Treaty of San Francisco

The , also called the , re-established peaceful relations between Japan and the Allied Powers on behalf of the United Nations by ending the legal state of war and providing for redress for hostile actions up to and including World War II. It w ...

, which was to end the occupation, was signed on September 8, 1951. It came into effect on April 28, 1952, formally ending all occupation powers of the Allied forces and restoring full sovereignty to Japan, except for the island chains of Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high.

...

and Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

, which the United States continued to hold. Iwo Jima was returned to Japan in 1968, and most of Okinawa was returned in 1972.

As a condition of securing the end of the Occupation and the restoration of Japanese sovereignty, Japan was compelled by the United States to agree to the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty

The , more commonly known as the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in English and as the or just in Japanese, is a treaty that permits the presence of U.S. military bases on Japanese soil, and commits the two nations to defend each other if one or th ...

, which has allowed U.S. troops to remain based on Japanese soil on an indefinite basis. Even after the Occupation officially ended in 1952, a

total of 260,000 American soldiers remained based on mainland Japan (exclusive of U.S.-controlled Okinawa, which based tens of thousands more). Even today, some 31,000 U.S. military personnel remain based in Japan, including at major bases near Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

, Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the ...

, Aomori

is the capital city of Aomori Prefecture, in the Tōhoku region of Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 278,964 in 136,457 households, and a population density of 340 people per square kilometer spread over the city's total area of ...

, Sapporo

( ain, サッ・ポロ・ペッ, Satporopet, lit=Dry, Great River) is a city in Japan. It is the largest city north of Tokyo and the largest city on Hokkaido, the northernmost main island of the country. It ranks as the fifth most populous city ...

, and Ishikari.

Popular anger at the continuing presence of these U.S. military bases in Japan even after the official end of the Occupation continued to grow over the course of the 1950s, leading to a nationwide anti-base movement and a number of spectacular protests, including Bloody May Day

refers to a violent conflict that took place between protesters and police officers in the Kokyo Gaien National Garden in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, Japan, on May 1, 1952. When a large crowd protesting the U.S.—Japan Security Tr ...

in 1952, the Sunagawa protests from 1955 to 1957, and the Girard Incident protests in 1957. Partially in response to these protests, the original 1951 Security Treaty was revised into a somewhat less one-sided pact in 1960, resulting in the current U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, which has had the effect of establishing a military alliance between the United States and Japan. However, even the revised treaty was opposed by many in Japan, leading to the massive 1960 Anpo protests, which were the largest protests in Japan's modern history.

Since the end of the Occupation, the United States has continuously pressured Japan to revise its American-imposed constitution to remove Article 9 and fully remilitarize. As a result, in 1954 the National Police Reserve

The , or NPR, was a lightly armed national police force established in August 1950 during the Allied occupation of Japan. In October 1952, it was expanded to 110,000 men and renamed as the . On July 1, 1954, it was reorganized as the Japan Groun ...

was reorganized into the Japan Self-Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, the ...

, a ''de facto'' military force, with U.S. assistance. However, thus far Japan has resisted U.S. pressures to fully rearm and remilitarize. Under the Yoshida Doctrine

The Yoshida Doctrine was a strategy adopted by Japan after its defeat in 1945 under Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, the prime minister 1948–1954. He concentrated upon reconstructing Japan's domestic economy while relying heavily on the security ...

, Japan continued to prioritize economic growth over defense spending, relying on American military protection to ensure it could focus mainly on economic recovery. Through "guided capitalism," Japan was able to use its resources to economically recover from the war and revive industry, eventually sparking a lengthy period of unprecedented economic growth remembered as the Japanese economic miracle

The Japanese economic miracle refers to Japan's record period of economic growth between the post-World War II era and the end of the Cold War. During the economic boom, Japan rapidly became the world's second-largest economy (after the Unit ...

.

Impact

Prostitution

With the acceptance of the Allied occupation authorities, the Japanese organized a

With the acceptance of the Allied occupation authorities, the Japanese organized a brothel

A brothel, bordello, ranch, or whorehouse is a place where people engage in sexual activity with prostitutes. However, for legal or cultural reasons, establishments often describe themselves as massage parlors, bars, strip clubs, body rub par ...

system (the euphemistically named "Recreation and Amusement Association

The or RAA, was the largest of the organizations established by Japanese authorities to provide organized prostitution to prevent rapes and sexual violence by Allied occupation troops on the general population,Schrijvers, Peter (2002). The GI W ...

," or RAA) for the benefit of the more than 300,000 occupation troops.[

In December 1945, a senior officer with the Public Health and Welfare Division of the occupation's General Headquarters wrote regarding the typical prostitute: "The girl is impressed into contracting by the desperate financial straits of her parents and their urging, occasionally supplemented by her willingness to make such a sacrifice to help her family", he wrote. "It is the belief of our informants, however, that in urban districts the practice of enslaving girls, while much less prevalent than in the past, still exists. The worst victims ... were the women who, with no previous experience, answered the ads calling for 'Women of the New Japan.'"][

MacArthur issued an order, SCAPIN 642 (SCAP Instruction), on January 21 ending licensed brothels for being "in contravention of the ideals of democracy". Although SCAPIN 642 ended the RAA's operations, it did not affect "voluntary prostitution" by individuals. Ultimately, SCAP responded by making all brothels and other facilities offering prostitution off-limits to Allied personnel on March 25, 1946. By November, the Japanese government had introduced the new system in which prostitution was permissible only in certain designated areas.]

Rape

According to Toshiyuki Tanaka, 76 cases of rape or rape-murder were reported during the first five years of the American occupation of Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

. However, he asserts this is probably not the true figure, as most cases were unreported. Some historians have estimated that U.S. troops committed thousands of rapes among the population of the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yonaguni ...

during the Okinawa Campaign

The , codenamed Operation Iceberg, was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army (USA) and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA). The initial invasion of ...

and the beginning of the American occupation in 1945. One Okinawan historian estimated as many as 10,000 Okinawan women may have been raped in total.

As described above, Japanese authorities had set up a large system of prostitution facilities in order to protect the population from sexual assault. According to John W. Dower

John W. Dower (born June 21, 1938 in Providence, Rhode Island, Providence, Rhode Island) is an American author and historian. His 1999 book ''Embracing Defeat, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II'' won the U.S. National Book Awar ...

, precisely as the Japanese government had hoped when it created the prostitution facilities, while the RAA was in place "the incidence of rape remained relatively low given the huge size of the occupation force." However, there was a resulting large rise in venereal disease among the soldiers, which led MacArthur to close down the prostitution in early 1946. The incidence of rape increased after the closure of the brothels, possibly eight-fold; Dower states that "According to one calculation the number of rapes and assaults on Japanese women amounted to around 40 ''daily'' while the RAA was in operation, and then rose to an average of 330 a day after it was terminated in early 1946." Brian Walsh disputes Dower's numbers and states that rape was uncommon throughout the Occupation, with the number of daily rapes being much lower. According to Walsh, the increase in rapes during the termination of the RAA was brief in duration, and the numbers quickly declined thereafter. Michael S. Molasky states that while rape and other violent crime were widespread in naval ports like Yokosuka

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

, the city has a population of 409,478, and a population density of . The total area is . Yokosuka is the 11th most populous city in the Greater Tokyo Area, and the 12th in the Kantō region.

The city ...

and Yokohama

is the second-largest city in Japan by population and the most populous municipality of Japan. It is the capital city and the most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a 2020 population of 3.8 million. It lies on Tokyo Bay, south of To ...

during the first few weeks of occupation, according to Japanese police reports and journalistic studies, the number of incidents declined shortly after and they were not common on mainland Japan throughout the rest of occupation.

Censorship

After the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

in 1945, SCAP abolished all forms of Japanese censorship and controls on freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

, which would later be enshrined in Article 21 of the 1947 Constitution of Japan

The Constitution of Japan (Shinjitai: , Kyūjitai: , Hepburn: ) is the constitution of Japan and the supreme law in the state. Written primarily by American civilian officials working under the Allied occupation of Japan, the constitution r ...

. However, two weeks into the Occupation, SCAP began censoring all media; on September 10, 1945, SCAP "issued press and pre-censorship codes outlawing the publication of all reports and statistics 'inimical to the objectives of the Occupation'." This included any mention of rape or other sensitive social issues.[.]

According to David M. Rosenfeld:

Japanese women

It has been argued that the granting of rights to women played an important role in the radical shift Japan underwent from a war nation to a democratized and demilitarized

A demilitarized zone (DMZ or DZ) is an area in which treaties or agreements between nations, military powers or contending groups forbid military installations, activities, or personnel. A DZ often lies along an established frontier or bounda ...