Death Of Socrates on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The trial of Socrates (399 BC) was held to determine the philosopher's guilt of two charges: ''

The formal accusation was the second element of the trial of Socrates, which the accuser,

The formal accusation was the second element of the trial of Socrates, which the accuser,

2.3.15–16

/ref> Moreover, the Thirty Tyrants also appointed a council of 500 men to perform the judicial functions that once had belonged to every Athenian citizen. In their brief régime, the Spartan oligarchs killed about five percent of the Athenian population, confiscated much property, and exiled democrats from the city proper. The fact that Critias, leader of the Thirty Tyrants, had been a pupil of Socrates was held against him. Plato's presentation of the trial and death of Socrates inspired writers, artists, and philosophers to revisit the matter. For some, the execution of the man whom Plato called "the wisest and most just of all men" demonstrated the defects of democracy and of popular rule; for others, the Athenian actions were a justifiable defence of the recently re-established democracy.

The Trial of Socratesalternate link

– features photographs of the philosopher's haunts

Apology of Socrates - Read Online at Tufts.edu

* https://socratesontrial.org/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Socrates Ancient Greek law Direct democracy Socrates Society of ancient Greece Trials in Greece 399 BC History of Classical Athens Persecution of philosophers Religious persecution Events in ancient Greek philosophy

asebeia Asebeia (Ancient Greek: ἀσέβεια) was a criminal charge in ancient Greece for the "desecration and mockery of divine objects", for "irreverence towards the state gods" and disrespect towards parents and dead ancestors. It translates into En ...

'' (impiety

Impiety is a perceived lack of proper respect for something considered sacred. Impiety is often closely associated with sacrilege, though it is not necessarily a physical action. Impiety cannot be associated with a cult, as it implies a larger be ...

) against the pantheon

Pantheon may refer to:

* Pantheon (religion), a set of gods belonging to a particular religion or tradition, and a temple or sacred building

Arts and entertainment Comics

*Pantheon (Marvel Comics), a fictional organization

* ''Pantheon'' (Lone St ...

of Athens, and corruption of the youth of the city-state; the accusers cited two impious acts by Socrates: "failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges" and "introducing new deities".

The death sentence of Socrates was the legal consequence of asking politico-philosophic questions of his students, which resulted in the two accusations of moral corruption and impiety. At trial, the majority of the ''dikast

Dikastes ( el, δικαστής, pl. δικασταί) was a legal office in ancient Greece that signified, in the broadest sense, a judge or juror, but more particularly denotes the Attic functionary of the democratic period, who, with his collea ...

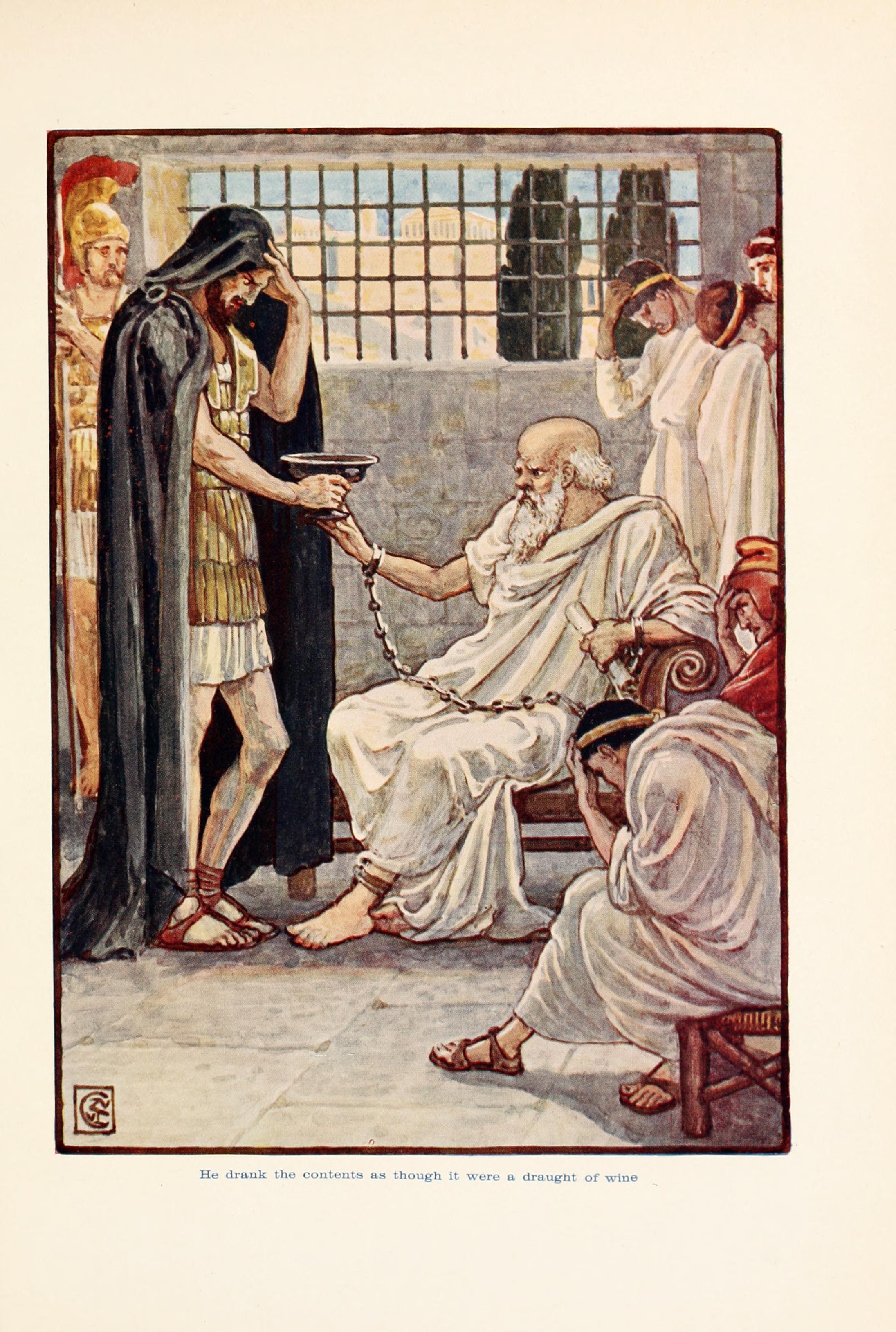

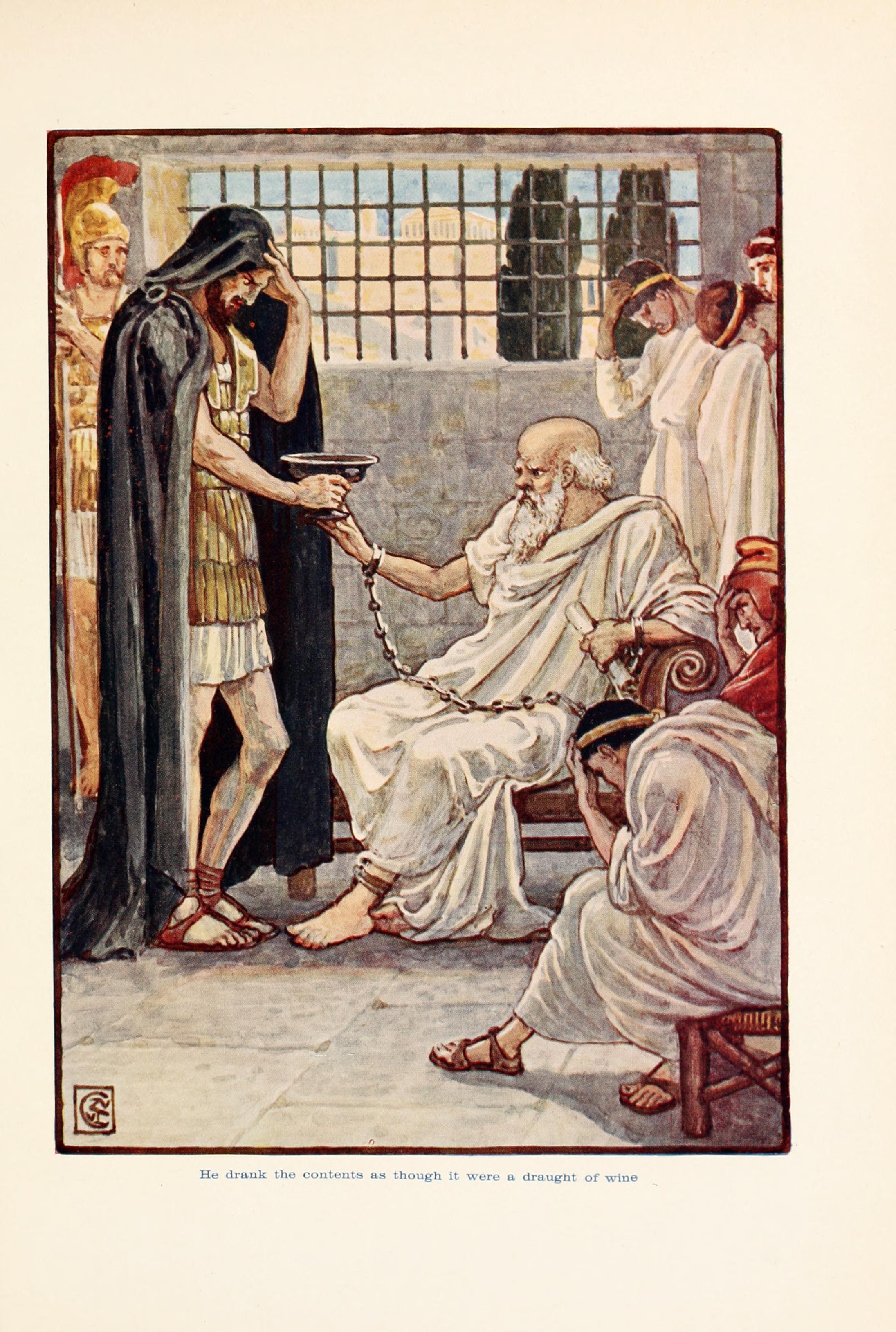

s'' (male-citizen jurors chosen by lot) voted to convict him of the two charges; then, consistent with common legal practice voted to determine his punishment and agreed to a sentence of death to be executed by Socrates's drinking a poisonous beverage of hemlock.

Primary-source accounts of the trial and execution of Socrates are the '' Apology of Socrates'' by Plato and the '' Apology of Socrates to the Jury'' by Xenophon of Athens

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

, who had also been his student; modern interpretations include ''The Trial of Socrates'' (1988) by the journalist I. F. Stone

Isidor Feinstein "I. F." Stone (December 24, 1907 – June 18, 1989) was an American investigative journalist, writer, and author.

Known for his politically progressive views, Stone is best remembered for ''I. F. Stone's Weekly'' (1953–1971), ...

, and ''Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths'' (2009) by the Classics scholar Robin Waterfield.

Background

Before the philosopher Socrates was tried for moral corruption and impiety, the citizens of Athens knew him as an intellectual and moral gadfly of their society. In the comic play, '' The Clouds'' (423 BC), Aristophanes represents Socrates as a sophistic philosopher who teaches the young man Pheidippides how to formulate arguments that justify striking and beating his father. Despite Socrates denying he had any relation with the Sophists, the playwright indicates that Athenians associated the philosophic teachings of Socrates with Sophism. As philosophers, the Sophists were men of ambiguous reputation, "they were a set of charlatans that appeared in Greece in the fifth century BC, and earned ample livelihood by imposing on public credulity: professing to teach virtue, they really taught the art of fallacious discourse, and meanwhile propagated immoral practical doctrines." Besides ''The Clouds'', the comic play '' The Wasps'' (422 BC) also depicts inter-generational conflict, between an older man and a young man. Such representations of inter-generational social conflict among the men of Athens, especially in the decade from 425 to 415 BC, can reflect contrasting positions regarding opposition to or support for the Athenian invasion of Sicily.Waterfield, Robin. ''Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths''. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009. Many Athenians blamed the teachings of the Sophists and of Socrates for instilling the younger generation with a morally nihilistic, disrespectful attitude towards their society. Socrates left no written works; however, his student and friend, Plato, wroteSocratic dialogue

Socratic dialogue ( grc, Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the p ...

s, featuring Socrates as the protagonist. As a teacher, competitor intellectuals resented Socrates's ''elenctic examination'' method for intellectual inquiry, because its questions threatened their credibility as men of wisdom and virtue.

It has sometimes been claimed that Socrates described himself as the "gadfly

Gadfly most commonly refers to:

* Horse-fly or Botfly

* Gadfly (philosophy and social science), a person who upsets the status quo

Gadfly may also refer to:

Entertainment

* ''The Gadfly'', an 1897 novel by Ethel Lilian Voynich

** ''The Gadfly'' ...

" of Athens which, like a sluggish horse, needed to be aroused by his "stinging". In the Greek text of his defense given by Plato, Socrates never actually uses that term (viz., "gadfly" oîstros''">:wiktionary:oestrus.html" ;"title="rk., '':wiktionary:oestrus">oîstros'' to describe himself. Rather, his reference is merely allusive, as he (literally) says only that he has attached himself to the City (''proskeimenon tē polei'') in order to sting it. Nevertheless, he does make the bold claim that he is a god's gift to the Athenians.

Socrates's elenctic method was often imitated by the young men of Athens.

Association with Alcibiades and the Thirty Tyrants

Alcibiades was an Athenian general who had been the main proponent of the disastrous Sicilian Expedition during the Peloponnesian Wars, where virtually the entire Athenian invading force of more than 50,000 soldiers and non-combatants (e.g., the rowers of the Triremes) was killed or captured and enslaved. He was a student and close friend of Socrates, and his messmate during the siege of Potidaea (433–429 BC). Socrates remained Alcibiades's close friend, admirer, and mentor for about five or six years.Waterfield, Robin. ''Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths''. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009. During his career, Alcibiades famously defected to Sparta, arch-enemy of Athens, after being summoned to trial, then to Persia after being caught in an affair with the wife of his benefactor (the King of Sparta). He then defected back to Athens after successfully persuading the Athenians that Persia would come to their aid against Sparta (though Persia had no intention of doing so). Finally driven out of Athens after the defeat of the Battle of Notium against Sparta, Alcibiades was assassinated inPhrygia

In classical antiquity, Phrygia ( ; grc, Φρυγία, ''Phrygía'' ) was a kingdom in the west central part of Anatolia, in what is now Asian Turkey, centered on the Sangarios River. After its conquest, it became a region of the great empires ...

in 400 BC by his Spartan enemies.

Another possible source of resentment was the political views that he and his associates were thought to have embraced. Critias, who appears in two of Plato's Socratic dialogues, was a leader of the Thirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants ( grc, οἱ τριάκοντα τύραννοι, ''hoi triákonta týrannoi'') were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Upon Lysander's request, the Thirty were elec ...

(the ruthless oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a conceptual form of power structure in which power rests with a small number of people. These people may or may not be distinguished by one or several characteristics, such as nobility, fame, wealth, education, or corporate, r ...

regime that ruled Athens, as puppets of Sparta and backed by Spartan troops, for eight months in 404–403 BC until they were overthrown). Several of the Thirty had been students of Socrates, but there is also a record of their falling out.

As with many of the issues surrounding Socrates's conviction, the nature of his affiliation with the Thirty Tyrants is far from straightforward. During the reign of the Thirty, many prominent Athenians who were opposed to the new government left Athens. Robin Waterfield asserts that "Socrates would have been welcome in oligarchic Thebes, where he had close associates among the Pythagoreans who flourished there, and which had already taken in other exiles." Given the availability of a hospitable host outside of Athens, Socrates, at least in a limited way, chose to remain in Athens. Thus, Waterfield suggests, Socrates's contemporaries probably thought his remaining in Athens, even without participating in the Thirty's bloodthirsty schemes, demonstrated his sympathy for the Thirty's cause, not neutrality towards it. This is proved, Waterfield argues, by the fact that after the Thirty were no longer in power, anyone who had remained in Athens during their rule was encouraged to move to Eleusis, the new home of the expatriate Thirty. Socrates did oppose the will of the Thirty on one documented occasion. Plato's ''Apology'' has the character of Socrates describe that the Thirty ordered him, along with four other men, to fetch a man named Leon from Salamis so that the Thirty could execute him. While Socrates did not obey this order, he did nothing to warn Leon, who was subsequently apprehended by the other four men.

Support of oligarchic rule and contempt for Athenian democracy

According to the portraits left by some of Socrates's followers, Socrates himself seems to have openly espoused certain anti-democratic views, the most prominent perhaps being the view that it is not majority opinion that yields correct policy but rather genuine knowledge and professional competence, which is possessed by only a few. Plato also portrays him as being severely critical of some of the most prominent and well-respected leaders of the Athenian democracy; and even has his claim that the officials selected by the Athenian system of governance cannot credibly be regarded as benefactors since it is not any group of ''many'' that benefits, but only "someone or very few persons". Finally, Socrates was known as often praising the laws of the undemocratic regimes of Sparta and Crete. Plato himself reinforced anti-democratic ideas in '' The Republic'', advocating rule by elite, enlightened "Philosopher-Kings". The totalitarian Thirty Tyrants had anointed themselves as the elite, and in the minds of his Athenian accusers, Socrates was guilty because he was suspected of introducing oligarchic ideas to them.Larry Gonick

Larry Gonick (born 1946) is a cartoonist best known for ''The Cartoon History of the Universe'', a history of the world in comic book form, which he published in installments from 1977 to 2009. He has also written ''The Cartoon History of the U ...

, in his "Cartoon History of the Universe

''The Cartoon History of the Universe'' is a book series about the history of the world. It is written and illustrated by American cartoonist, professor, and mathematician Larry Gonick, who started the project in 1978. Each book in the series ex ...

" wrote:

Apart from his views on politics, Socrates held unusual views on religion. He made several references to his spirit, or '' daimonion'', although he explicitly claimed that it never urged him on, but only warned him against various prospective actions.

Historical descriptions of the trial

The extant, primary sources about the history of the trial and execution of Socrates are: the '' Apology of Socrates to the Jury'', by Xenophon, a historian; and thetetralogy

A tetralogy (from Greek τετρα- ''tetra-'', "four" and -λογία ''-logia'', "discourse") is a compound work that is made up of four distinct works. The name comes from the Attic theater, in which a tetralogy was a group of three tragedies ...

of Socratic dialogues'' Euthyphro'', the '' Socratic Apology'', '' Crito'', and '' Phaedo'', by Plato, a philosopher who had been a student of Socrates.

In ''The Indictment of Socrates'' (392 BC), the sophist rhetorician Polycrates (440–370) presents the prosecution speech by Anytus, which condemned Socrates for his political and religious activities in Athens before the year 403 BC. In presenting such a prosecution, which addressed matters external to the specific charges of moral corruption and impiety levelled by the Athenian '' polis'' against Socrates, Anytus violated the political amnesty specified in the agreement of reconciliation (403–402 BC), which granted pardon to a man for political and religious actions taken before or during the rule of the Thirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants ( grc, οἱ τριάκοντα τύραννοι, ''hoi triákonta týrannoi'') were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Upon Lysander's request, the Thirty were elec ...

, "under which all further charges and official recriminations concerning the eign ofterror were forbidden".

Moreover, the legal and religious particulars against Socrates that Polycrates reported in ''The Indictment of Socrates'' are addressed in the replies by Xenophon and the sophist Libanius of Antioch (314–390).

Trial

The formal accusation was the second element of the trial of Socrates, which the accuser,

The formal accusation was the second element of the trial of Socrates, which the accuser, Meletus Meletus ( el, Μέλητος; fl. 5th–4th century BCE) was an ancient Athenian Greek from the Pithus deme known for his prosecuting role in the trial and eventual execution of the philosopher Socrates.

Life

Little is known of Meletus' life beyon ...

, swore to be true, before the archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

(a state officer with mostly religious duties) who considered the evidence and determined that there was an actionable case of "moral corruption of Athenian youth" and "impiety

Impiety is a perceived lack of proper respect for something considered sacred. Impiety is often closely associated with sacrilege, though it is not necessarily a physical action. Impiety cannot be associated with a cult, as it implies a larger be ...

", for which the philosopher must legally answer; the archon summoned Socrates for a trial by jury.

Athenian juries were drawn by lottery, from a group of hundreds of male-citizen volunteers; such a great jury usually ensured a majority verdict in a trial. Although neither Plato nor Xenophon of Athens

Xenophon of Athens (; grc, Ξενοφῶν ; – probably 355 or 354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian, born in Athens. At the age of 30, Xenophon was elected commander of one of the biggest Greek mercenary armies of ...

identifies the number of jurors, a jury of 501 men likely was the legal norm. In the '' Apology of Socrates'' (36a–b), about Socrates's defence at trial, Plato said that if just 30 of the votes had been otherwise, then Socrates would have been acquitted (36a), and that (perhaps) less than three-fifths of the jury voted against him (36b). Assuming a jury of 501, this would imply that he was convicted by a majority of 280 against 221.

Having been found guilty of corruption and impiety, Socrates and the prosecutor suggested sentences for the punishment of his crimes against the city-state of Athens. Expressing surprise at the few votes required for an acquittal, Socrates joked that he be punished with free meals at the Prytaneum (the city's sacred hearth), an honour usually held for a benefactor

Benefactor may refer to:

* ''Benefactor'' (album), a 1982 album by Romeo Void

* Benefactor (law) for a person whose actions benefit another or a person that gives back to others

* Benefication (metallurgy)

In the mining

Mining is the ext ...

of Athens, and the victorious athletes of an Olympiad. After that failed suggestion, Socrates then offered to pay a fine of 100 drachmaeone-fifth of his propertywhich largesse testified to his integrity and poverty as a philosopher. Finally, a fine of 3,000 drachmae was agreed, proposed by Plato, Crito, Critobulus, and Apollodorus, who guaranteed paymentnonetheless, the prosecutor of the trial of Socrates proposed the death penalty for the impious philosopher. (Diogenes Laërtius, 2.42). In the end, the sentence of death was passed by a greater majority of the jury than that by which he had been convicted.

In the event, friends, followers, and students encouraged Socrates to flee Athens, an action which the citizens expected; yet, on principle, Socrates refused to flout the law and escape his legal responsibility to Athens (see: '' Crito''). Therefore, faithful to his teaching of civic obedience to the law, the 70-year-old Socrates executed his death sentence and drank the hemlock, as condemned at trial. (See: '' Phaedo'')

Interpretations of the trial of Socrates

Ancient

In the time of the trial of Socrates, the year 399 BC, the city-state of Athens recently had endured the trials and tribulations of Spartan hegemony and the thirteen-month régime of theThirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants ( grc, οἱ τριάκοντα τύραννοι, ''hoi triákonta týrannoi'') were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Upon Lysander's request, the Thirty were elec ...

, which had been imposed consequently to the Athenian defeat in the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC) was an ancient Greek war fought between Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Greek world. The war remained undecided for a long time until the decisive intervention of th ...

(431–404 BC). At the request of Lysander, a Spartan admiral, the Thirty men, led by Critias and Theramenes, were to administer Athens and revise the city's democratic laws, which were inscribed on a wall of the Stoa Basileios. Their actions were to facilitate the transition of the Athenian government from a democracy to an oligarchy in service to Sparta.Xenophon, ''Hellenica''2.3.15–16

/ref> Moreover, the Thirty Tyrants also appointed a council of 500 men to perform the judicial functions that once had belonged to every Athenian citizen. In their brief régime, the Spartan oligarchs killed about five percent of the Athenian population, confiscated much property, and exiled democrats from the city proper. The fact that Critias, leader of the Thirty Tyrants, had been a pupil of Socrates was held against him. Plato's presentation of the trial and death of Socrates inspired writers, artists, and philosophers to revisit the matter. For some, the execution of the man whom Plato called "the wisest and most just of all men" demonstrated the defects of democracy and of popular rule; for others, the Athenian actions were a justifiable defence of the recently re-established democracy.

Modern

In ''The Trial of Socrates'' (1988),I. F. Stone

Isidor Feinstein "I. F." Stone (December 24, 1907 – June 18, 1989) was an American investigative journalist, writer, and author.

Known for his politically progressive views, Stone is best remembered for ''I. F. Stone's Weekly'' (1953–1971), ...

argued that Socrates wanted to be sentenced to death, to justify his philosophic opposition to the Athenian democracy of that time, and because, as a man, he saw that old age would be an unpleasant time for him.

In the introduction to his play ''Socrates on Trial

''Socrates on Trial'' is a Play (theatre), play depicting the life and death of the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates. It tells the story of how Socrates was put on trial for corrupting the youth of Athens and for failing to honour the city's g ...

'' (2007), Andrew Irvine claimed that because of his loyalty to Athenian democracy, Socrates willingly accepted the guilty verdict voted by the jurors at his trial:

In ''Why Socrates Died: Dispelling the Myths'' (2009), Robin Waterfield wrote that the death of Socrates was an act of volition motivated by a greater purpose; Socrates "saw himself as healing the City's ills by his voluntary death". Waterfield wrote that Socrates, with his unconventional methods of intellectual enquiry, attempted to resolve the political confusion then occurring in the city-state of Athens, by willingly being the scapegoat, whose death would quiet old disputes, which then would allow the Athenian polis to progress towards political harmony and social peace.

In ''The New Trial of Socrates'' (2012), an international panel of ten judges held a mock re-trial of Socrates to resolve the matter of the charges levelled against him by Meletus Meletus ( el, Μέλητος; fl. 5th–4th century BCE) was an ancient Athenian Greek from the Pithus deme known for his prosecuting role in the trial and eventual execution of the philosopher Socrates.

Life

Little is known of Meletus' life beyon ...

, Anytus, and Lycon, that: "Socrates is a doer of evil and corrupter of the youth, and he does not believe in the gods of the state, and he believes in other new divinities of his own". Five judges voted guilty and five judges voted not guilty. Limiting themselves to the facts of the case against Socrates, the judges did not consider any sentence, but the judges who voted the philosopher guilty said that they would not have considered the death penalty for him.

Rhetorical scholar Collin Bjork contended that Plato's depiction of the trial makes an important contribution to rhetorical theories of ethos, one that countered "prevailing notions of rhetoric as an art primarily concerned with making individual speeches and foreground dinstead the rhetorical impact of a ''lifetime'' of philosophical-cum-rhetorical activity" (258).

See also

* Meno * Phaedo * The unexamined life is not worth livingReferences

Further reading

* * * * * * * * Filonik, Jakub (2013). "Athenian impiety trials: a reappraisal". ''Dike: rivista di storia del diritto greco ed ellenistico'' 16: 11–96. * * (cloth); (paper); (e-pub) * * * * * * * * * *External links

* The University of Missouri–Kansas City (UMKC) School of LawThe Trial of Socrates

– features photographs of the philosopher's haunts

Apology of Socrates - Read Online at Tufts.edu

* https://socratesontrial.org/ {{DEFAULTSORT:Socrates Ancient Greek law Direct democracy Socrates Society of ancient Greece Trials in Greece 399 BC History of Classical Athens Persecution of philosophers Religious persecution Events in ancient Greek philosophy