Death of Marilyn Monroe on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

At 4:30 p.m. PDT, Monroe's psychiatrist Ralph Greenson arrived at the house to conduct a therapy session and asked Newcomb to leave. Before Greenson left at around 7 p.m., he asked Murray to stay overnight and keep Monroe company. At approximately 7–7:15, Monroe received a call from Joe DiMaggio Jr., with whom she had stayed close since her divorce from his father, the elder

At 4:30 p.m. PDT, Monroe's psychiatrist Ralph Greenson arrived at the house to conduct a therapy session and asked Newcomb to leave. Before Greenson left at around 7 p.m., he asked Murray to stay overnight and keep Monroe company. At approximately 7–7:15, Monroe received a call from Joe DiMaggio Jr., with whom she had stayed close since her divorce from his father, the elder

Monroe's unexpected death was front-page news in the United States and Europe. According to biographer

Monroe's unexpected death was front-page news in the United States and Europe. According to biographer

Capell's credibility has been seriously questioned because his only source was columnist

Capell's credibility has been seriously questioned because his only source was columnist

The most prominent Monroe conspiracy theorist in the 1980s was British journalist Anthony Summers, who claimed that Monroe's death was an accidental overdose enabled and covered up by Robert F. Kennedy. His book, ''Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe'' (1985), became one of the most commercially successful Monroe biographies. Prior to writing on Monroe, he had authored a book on a conspiracy theory of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. His investigation on Monroe began as an assignment for the British tabloid the ''

The most prominent Monroe conspiracy theorist in the 1980s was British journalist Anthony Summers, who claimed that Monroe's death was an accidental overdose enabled and covered up by Robert F. Kennedy. His book, ''Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe'' (1985), became one of the most commercially successful Monroe biographies. Prior to writing on Monroe, he had authored a book on a conspiracy theory of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. His investigation on Monroe began as an assignment for the British tabloid the ''

"Marilyn Monroe Dead, Pills Near"

Articles of Monroe's death in ''

"From the Archives: Marilyn Monroe Dies; Pills Blamed"

in ''

"Funeral for a Hollywood legend: The death of Marilyn Monroe

in ''Los Angeles Times''

"Marilyn Monroe Is Dead"

in ''

"Marilyn is Dead

Obituary in ''

"Death of Marilyn Monroe"

A ''

Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe (; born Norma Jeane Mortenson; 1 June 1926 4 August 1962) was an American actress. Famous for playing comedic " blonde bombshell" characters, she became one of the most popular sex symbols of the 1950s and early 1960s, as wel ...

died at age 36 of a barbiturate overdose

Barbiturate overdose is poisoning due to excessive doses of barbiturates. Symptoms typically include difficulty thinking, poor coordination, decreased level of consciousness, and a decreased effort to breathe (respiratory depression). Complicat ...

late in the evening of Saturday, August 4, 1962, at her 12305 Fifth Helena Drive

12305 Fifth Helena Dr. is a home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, California. The house is most famous as the final residence of Marilyn Monroe and the location of her death on August 4, 1962.

Location

The property is located at 12305 Fifth Helena Dr ...

home in Los Angeles, California. Her body was discovered before dawn on Sunday, August 5. She was one of the most popular Hollywood stars during the 1950s and early 1960s, was considered a major sex symbol at the time, and was a top-billed actress for a decade. Monroe's films had grossed $200 million by the time of her death.

Monroe had suffered from mental illness and substance abuse for several years prior to her death, and she had not completed a film since '' The Misfits'', released on February 1, 1961; the movie was a box-office disappointment. Monroe had spent 1961 preoccupied with her various health problems, and in April 1962 had begun filming ''Something's Got to Give

''Something's Got to Give'' is an unfinished American feature film shot in 1962, directed by George Cukor for 20th Century Fox and starring Marilyn Monroe, Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse. A remake of '' My Favorite Wife'' (1940), a screwball comed ...

'' for 20th Century Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film studio, film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm o ...

, but the studio fired her in early June. The studio publicly blamed her for the production's problems, and in the weeks preceding her death she had attempted to repair her public image by giving several interviews to high-profile publications. Monroe also began negotiations with Fox on being re-hired for ''Something's Got to Give'' and for starring roles in other productions.

Monroe spent the last day of her life, August 4, at her home in Brentwood. She was accompanied at various times by publicist Patricia Newcomb

Margot Patricia "Pat" Newcomb Wigan (born July 9, 1930) is an American publicist and producer. After working for Pierre Salinger, she was hired by the agency of Arthur P. Jacobs and briefly represented Marilyn Monroe in 1956. In 1960, she became ...

, housekeeper Eunice Murray, photographer Lawrence Schiller

Lawrence Julian Schiller (born December 28, 1936) is an American photojournalist, film producer, director and screenwriter.

Career

Schiller was born in 1936 in Brooklyn to Jewish parents and grew up outside of San Diego, California. After atten ...

and psychiatrist Ralph Greenson. At Greenson's request, Murray stayed overnight to keep Monroe company. At approximately 3 a.m. on Sunday, August 5, she noticed that Monroe had locked herself in her bedroom and appeared unresponsive when she looked into the bedroom through a window. Murray alerted Greenson, who arrived soon after, entered the room by breaking a window, and found Monroe dead. Her death was officially ruled a probable suicide by the Los Angeles County coroner's office, based on precedents of her overdosing and being prone to mood swings and suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, means having thoughts, ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of ending one's own life.World Health Organization, ''ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics'', ver. 09/2020MB26.A Suicidal ideatio ...

. No evidence of foul play was found, and accidental overdose was ruled out because of the large amount of barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential as ...

s she had ingested. Her funeral on August 8, arranged by her former husband Joe DiMaggio

Joseph Paul DiMaggio (November 25, 1914 – March 8, 1999), nicknamed "Joltin' Joe", "The Yankee Clipper" and "Joe D.", was an American baseball center fielder who played his entire 13-year career in Major League Baseball for the New York Ya ...

, took place at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, then she was interred in a crypt at the Corridor of Memories.

Despite the coroner's findings, several conspiracy theories suggesting murder or accidental overdose have been proposed since the mid-1960s. Many of these involve U.S. President John F. Kennedy and his brother, Robert

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, h ...

, as well as union leader Jimmy Hoffa

James Riddle Hoffa (born February 14, 1913 – disappeared July 30, 1975; declared dead July 30, 1982) was an American labor union leader who served as the president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) from 1957 until 1971.

F ...

and mob boss Sam Giancana

Salvatore Mooney Giancana (; born Gilormo Giangana; ; May 24, 1908 – June 19, 1975) was an American mobster who was boss of the Chicago Outfit from 1957 to 1966.

Giancana was born in Chicago to Italian immigrant parents. He joined the 42 ...

. Because of the prevalence of these theories in the media, the office of the Los Angeles County District Attorney reviewed the case in 1982 but found no evidence to support them and did not disagree with the findings of the original investigation.

Background

For several years heading into the early 1960s, Marilyn Monroe had been dependent onamphetamine

Amphetamine (contracted from alpha- methylphenethylamine) is a strong central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), narcolepsy, and obesity. It is also commonly used ...

s, barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological addiction potential as ...

s and alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

, and she experienced various mental health problems that included depression, anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion which is characterized by an unpleasant state of inner turmoil

Turmoil may refer to:

* ''Turmoil'' (1984 video game), a 1984 video game released by Bug-Byte

* ''Turmoil'' (2016 video game), a 2016 indie oil tycoon video ...

, low self-esteem

Self-esteem is confidence in one's own worth or abilities. Self-esteem encompasses beliefs about oneself (for example, "I am loved", "I am worthy") as well as emotional states, such as triumph, despair, pride, and shame. Smith and Mackie (2007) d ...

, and chronic insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which people have trouble sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low energy ...

. She had acquired a reputation for being difficult to work with, and she frequently delayed productions by being late to film sets in addition to having trouble remembering her lines.

By 1960, this behavior was adversely affecting Monroe's career. For example, although she was the preferred choice of author Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

to play Holly Golightly in the film adaptation of '' Breakfast at Tiffany's'', Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

declined to cast her due to fear that she would complicate the film's production. The two films Monroe completed in the 1960s, ''Let's Make Love

''Let's Make Love'' is a 1960 American musical comedy film made by 20th Century Fox in DeLuxe Color and CinemaScope. Directed by George Cukor and produced by Jerry Wald from a screenplay by Norman Krasna, Hal Kanter, and Arthur Miller, the ...

'' (1960) and '' The Misfits'' (1961), were both critical and commercial failures. During the filming of the latter she had had to spend a week detoxing in a hospital. Her third marriage, to author Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are ''All My Sons'' (1947), ''Death of a Salesman'' (19 ...

, also ended in divorce in January 1961.

Instead of working, Monroe spent a large part of 1961 preoccupied with health problems and did not work on any new film projects. She underwent surgery for her endometriosis

Endometriosis is a disease of the female reproductive system in which cells similar to those in the endometrium, the layer of tissue that normally covers the inside of the uterus, grow outside the uterus. Most often this is on the ovaries, ...

and a cholecystectomy

Cholecystectomy is the surgical removal of the gallbladder. Cholecystectomy is a common treatment of symptomatic gallstones and other gallbladder conditions. In 2011, cholecystectomy was the eighth most common operating room procedure performed i ...

, and spent four weeks in hospital care—including a brief stint in a mental ward—for depression. Later in 1961, she moved back to Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the wor ...

after six years in Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five Boroughs of New York City, boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the List of co ...

; she purchased a Spanish hacienda

An ''hacienda'' ( or ; or ) is an estate (or '' finca''), similar to a Roman '' latifundium'', in Spain and the former Spanish Empire. With origins in Andalusia, ''haciendas'' were variously plantations (perhaps including animals or orchard ...

-style house at 12305 Fifth Helena Drive

12305 Fifth Helena Dr. is a home in Brentwood, Los Angeles, California. The house is most famous as the final residence of Marilyn Monroe and the location of her death on August 4, 1962.

Location

The property is located at 12305 Fifth Helena Dr ...

in Brentwood. In early 1962, she received a "World Film Favorite" Golden Globe award

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

and began to shoot a new film, ''Something's Got to Give

''Something's Got to Give'' is an unfinished American feature film shot in 1962, directed by George Cukor for 20th Century Fox and starring Marilyn Monroe, Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse. A remake of '' My Favorite Wife'' (1940), a screwball comed ...

'', a remake of ''My Favorite Wife

''My Favorite Wife'' (released in the U.K. as ''My Favourite Wife'') is a 1940 screwball comedy produced by Leo McCarey and directed by Garson Kanin. The picture stars Irene Dunne as a woman who, after being shipwrecked on a tropical island ...

'' (1940).

Days before filming began, Monroe caught sinusitis

Sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis, is inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the sinuses resulting in symptoms that may include thick nasal mucus, a plugged nose, and facial pain. Other signs and symptoms may include fever, he ...

; the studio, 20th Century Fox

20th Century Studios, Inc. (previously known as 20th Century Fox) is an American film studio, film production company headquartered at the Fox Studio Lot in the Century City area of Los Angeles. As of 2019, it serves as a film production arm o ...

, was advised to postpone the production, but the advice was not heeded and filming began on schedule in late April. Monroe was too ill to work for the majority of the next six weeks, but despite confirmations by multiple doctors, Fox tried to pressure her by publicly alleging that she was faking her symptoms. On May 19, Monroe took a break from filming to sing "Happy Birthday

Happy Birthday may refer to:

* "Happy Birthday", an expression of good will offered on a person's birthday

Film, theatre and television

* ''Happy Birthday'' (1998 film), a Russian drama by Larisa Sadilova

* ''Happy Birthday'', a 2001 film featu ...

" on stage at U.S. President John F. Kennedy's birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden

Madison Square Garden, colloquially known as The Garden or by its initials MSG, is a multi-purpose indoor arena in New York City. It is located in Midtown Manhattan between Seventh and Eighth avenues from 31st to 33rd Street, above Pennsyl ...

in New York ten days before his actual birthday.

After Monroe returned to Los Angeles, she resumed filming and celebrated her 36th birthday on the set on June 1. She was again absent for several days, which led Fox to fire her on June 7 and sue her for breach of contract, demanding $750,000 in damages. She was replaced by Lee Remick

Lee Ann Remick (December 14, 1935 – July 2, 1991) was an American actress and singer. She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for the film '' Days of Wine and Roses'' (1962), and for the 1966 Tony Award for Best Actress in ...

, but after co-star Dean Martin

Dean Martin (born Dino Paul Crocetti; June 7, 1917 – December 25, 1995) was an American singer, actor and comedian. One of the most popular and enduring American entertainers of the mid-20th century, Martin was nicknamed "The King of Cool". M ...

refused to make the film with anyone other than Monroe, Fox sued him as well and shut down the production.

Fox publicly blamed Monroe's drug addiction and alleged lack of professionalism for the demise of the film, even claiming that she was mentally disturbed. To counter the negative publicity, Monroe gave interviews to several high-profile publications, such as ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

'', '' Cosmopolitan'' and '' Vogue'', during the last weeks of her life. After successfully renegotiating her contract with Fox, filming with Monroe was scheduled to resume in September on ''Something's Got to Give'', and she made plans for starring in ''What a Way to Go!

''What a Way to Go!'' is a 1964 American black comedy film directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Shirley MacLaine, Paul Newman, Robert Mitchum, Dean Martin, Gene Kelly, Bob Cummings and Dick Van Dyke.

Plot

In a dream-like pre-credit sequ ...

'' (1964) as well as a biopic about Jean Harlow

Jean Harlow (born Harlean Harlow Carpenter; March 3, 1911 – June 7, 1937) was an American actress. Known for her portrayal of "bad girl" characters, she was the leading sex symbol of the early 1930s and one of the defining figures of the ...

.

Timeline

Monroe spent the last day of her life, Saturday, August 4, 1962, at her Brentwood home. In the morning, she met photographerLawrence Schiller

Lawrence Julian Schiller (born December 28, 1936) is an American photojournalist, film producer, director and screenwriter.

Career

Schiller was born in 1936 in Brooklyn to Jewish parents and grew up outside of San Diego, California. After atten ...

to discuss the possibility of ''Playboy

''Playboy'' is an American men's lifestyle and entertainment magazine, formerly in print and currently online. It was founded in Chicago in 1953, by Hugh Hefner and his associates, and funded in part by a $1,000 loan from Hefner's mother.

K ...

'' publishing nude photos taken of her on the set of ''Something's Got to Give''. She also received a massage from her personal massage therapist, talked with friends on the phone, and signed for deliveries. Also present at the house that morning were her housekeeper, Eunice Murray, and her publicist Patricia Newcomb

Margot Patricia "Pat" Newcomb Wigan (born July 9, 1930) is an American publicist and producer. After working for Pierre Salinger, she was hired by the agency of Arthur P. Jacobs and briefly represented Marilyn Monroe in 1956. In 1960, she became ...

, who had stayed overnight. According to Newcomb, they had an argument because Monroe had not slept well the night before.

At 4:30 p.m. PDT, Monroe's psychiatrist Ralph Greenson arrived at the house to conduct a therapy session and asked Newcomb to leave. Before Greenson left at around 7 p.m., he asked Murray to stay overnight and keep Monroe company. At approximately 7–7:15, Monroe received a call from Joe DiMaggio Jr., with whom she had stayed close since her divorce from his father, the elder

At 4:30 p.m. PDT, Monroe's psychiatrist Ralph Greenson arrived at the house to conduct a therapy session and asked Newcomb to leave. Before Greenson left at around 7 p.m., he asked Murray to stay overnight and keep Monroe company. At approximately 7–7:15, Monroe received a call from Joe DiMaggio Jr., with whom she had stayed close since her divorce from his father, the elder Joe DiMaggio

Joseph Paul DiMaggio (November 25, 1914 – March 8, 1999), nicknamed "Joltin' Joe", "The Yankee Clipper" and "Joe D.", was an American baseball center fielder who played his entire 13-year career in Major League Baseball for the New York Ya ...

. DiMaggio told Monroe that he had broken up with a girlfriend she did not like, and he detected nothing alarming in Monroe's behavior. At around 7:40–7:45, Monroe telephoned Greenson to tell him the news about the breakup of DiMaggio and his girlfriend.

Monroe retired to her bedroom at approximately 8 p.m. She received a call from actor Peter Lawford

Peter Sydney Ernest Lawford ( Aylen; 7 September 1923 – 24 December 1984) was an English-American actor.Obituary '' Variety'', 26 December 1984.

He was a member of the "Rat Pack" and the brother-in-law of US president John F. Kennedy and se ...

, who was hoping to persuade her to attend his party that night. Lawford became alarmed because Monroe sounded like she was under the influence of drugs. She told him, "Say goodbye to Pat, say goodbye to the president (Lawford's brother-in-law), and say goodbye to yourself, because you're a nice guy", before drifting off. Unable to reach Monroe, Lawford called his agent Milton Ebbins, who unsuccessfully tried to reach Greenson and later called Monroe's lawyer, Milton A. "Mickey" Rudin. Rudin called Monroe's house and was assured by Murray that she was fine.

At approximately 3:30 a.m. on Sunday, August 5, Murray woke up "sensing that something was wrong" and saw light from under Monroe's bedroom door, but she was not able to get a response and found the door locked. Murray telephoned Greenson, on whose advice she looked in through a window, and saw Monroe lying facedown on her bed, covered by a sheet and clutching a telephone receiver. Greenson arrived shortly thereafter. He entered the room by breaking a window and found Monroe dead. He called her physician, Hyman Engelberg, who arrived at the house at around 3:50 a.m. and officially confirmed the death. At 4:25 a.m., they notified the Los Angeles Police Department

The Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), officially known as the City of Los Angeles Police Department, is the municipal Police, police department of Los Angeles, California. With 9,974 police officers and 3,000 civilian staff, it is the thir ...

(LAPD).

Inquest and 1982 review

Deputy coroner Thomas Noguchi conducted Monroe's autopsy on the same day that she was found dead, Sunday, August 5. The Los Angeles County coroner's office was assisted in theinquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a co ...

by psychiatrists Norman Farberow, Robert Litman, and Norman Tabachnik from the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center, who interviewed Monroe's doctors and psychiatrists on her mental state. Based on the advanced state of ''rigor mortis

Rigor mortis (Latin: ''rigor'' "stiffness", and ''mortis'' "of death"), or postmortem rigidity, is the third stage of death. It is one of the recognizable signs of death, characterized by stiffening of the limbs of the corpse caused by chem ...

'' at the time her body was discovered, it was estimated that she had died between 8:30 and 10:30 p.m. on August 4.

The toxicological analysis concluded that the cause of death was acute barbiturate poisoning; she had 8 mg% (mg/dl) of chloral hydrate

Chloral hydrate is a geminal diol with the formula . It is a colorless solid. It has limited use as a sedative and hypnotic pharmaceutical drug. It is also a useful laboratory chemical reagent and precursor. It is derived from chloral (trich ...

and 4.5 mg% of pentobarbital

Pentobarbital (previously known as pentobarbitone in Britain and Australia) is a short-acting barbiturate typically used as a sedative, a preanesthetic, and to control convulsions in emergencies. It can also be used for short-term treatment o ...

(Nembutal) in her blood and a further 13 mg% of pentobarbital in her liver. The police found empty bottles of these medicines next to her bed. There were no signs of external wounds or bruises on the body.

The findings of the inquest were published on August 17; Chief Coroner Theodore Curphey classified Monroe's death a "probable suicide." The possibility of an accidental overdose was ruled out because the dosages found in her body were several times over the lethal limit and had been taken "in one gulp or in a few gulps over a minute or so." At the time of her death, Monroe was reported to have been in a "depressed mood", and had been "unkempt" and uninterested in maintaining her appearance. No suicide note was found, but Litman stated that this was not unusual, because statistics show that less than forty percent of suicide victims leave notes. In their final report, Farberow, Litman, and Tabachnik stated:

Miss Monroe had suffered from psychiatric disturbance for a long time. She experienced severe fears and frequent depressions. Mood changes were abrupt and unpredictable. Among symptoms of disorganization, sleep disturbance was prominent, for which she had been taking sedative drugs for many years. She was thus familiar with and experienced in the use of sedative drugs and well aware of their dangers ... In our investigation we have learned that Miss Monroe had often expressed wishes to give up, to withdraw, and even to die. On more than one occasion in the past, she had made a suicide attempt, using sedative drugs. On these occasions, she had called for help and had been rescued. It is our opinion that the same pattern was repeated on the evening of Aug. 4 except for the rescue. It has been our practice with similar information collected in other cases in the past to recommend a certification for such deaths as probable suicide. Additional clues for suicide provided by the physical evidence are the high level of barbiturates and chloral hydrate in the blood which, with other evidence from the autopsy, indicates the probable ingestion of a large amount of drugs within a short period of time: the completely empty bottle of Nembutal, the prescription for which (25 capsules) was filled the day before the ingestion, and the locked door to the bedroom, which was unusual.In the 1970s, claims surfaced that Monroe's death was a murder and not suicide. Due to these claims,

Los Angeles County District Attorney

The District Attorney of Los Angeles County is in charge of the office that prosecutes felony and misdemeanor crimes that occur within Los Angeles County, California, United States. The current district attorney (DA) is George Gascón.

Some ...

John Van de Kamp

John Kalar Van de Kamp (February 7, 1936 – March 14, 2017) was an American politician and lawyer who served as Los Angeles County District Attorney from 1975 until 1981, and then as the 28th Attorney General of California from 1983 until 1991 ...

assigned his colleague Ronald H. "Mike" Carroll to conduct a 1982 "threshold investigation" to see whether a criminal investigation should be opened. Carroll worked with Alan B. Tomich, an investigator for the district attorney's office, for over three months on an inquiry that resulted in a thirty-page report. They did not find any credible evidence to support the theory that Monroe was murdered.

In 1983, Noguchi published his memoirs, in which he discussed Monroe's case and the allegations of discrepancies in the autopsy and the coroner's ruling of suicide. These included the claims that Monroe could not have ingested the pills because her stomach was empty; that Nembutal capsules should have left yellow residue; that she may have been administered an enema

An enema, also known as a clyster, is an injection of fluid into the lower bowel by way of the rectum.Cullingworth, ''A Manual of Nursing, Medical and Surgical'':155 The word enema can also refer to the liquid injected, as well as to a devic ...

; and that the autopsy noted no needle marks despite the fact that she routinely received injections from her doctors. Noguchi explained that hemorrhaging

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

of the stomach lining indicated that the medication had been administered orally, and that because Monroe had been an addict for several years the pills would have been absorbed more rapidly than in the case of non-addicts. Noguchi also denied that Nembutal leaves dye residue, and he noted that only very recent needle marks are visible on a body, and that the only bruise he noted on Monroe's body, on her lower back, was superficial and its placement indicated that it was accidental and not linked to foul play. Noguchi finally concluded that based on his observations, the most probable conclusion is that Monroe committed suicide.

Public reactions and funeral

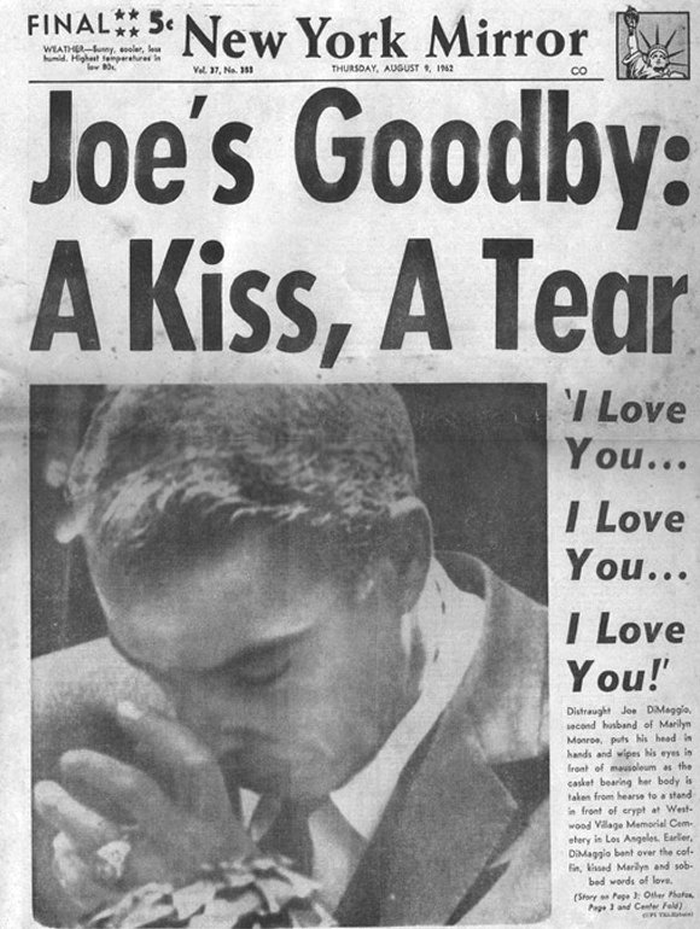

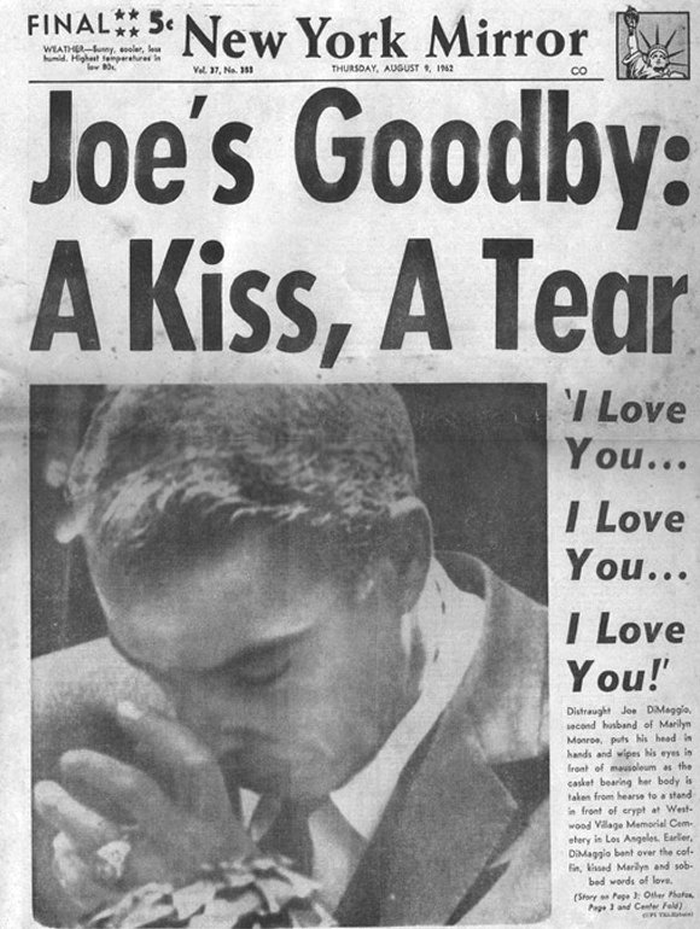

Monroe's unexpected death was front-page news in the United States and Europe. According to biographer

Monroe's unexpected death was front-page news in the United States and Europe. According to biographer Lois Banner

Lois Wendland Banner (born 1939) is an American author and emeritus professor of history at the University of Southern California. She is one of the earliest academics to focus on women's history in the United States."Lois W. Banner." ''Gale Lite ...

, "it's said that the suicide rate in Los Angeles doubled the month after she died; the circulation rate of most newspapers expanded that month." The ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

'' reported that they had received hundreds of phone calls from members of the public requesting information about her death. French artist Jean Cocteau

Jean Maurice Eugène Clément Cocteau (, , ; 5 July 1889 – 11 October 1963) was a French poet, playwright, novelist, designer, filmmaker, visual artist and critic. He was one of the foremost creatives of the s ...

commented that her death "should serve as a terrible lesson to all those, whose chief occupation consists of spying on and tormenting film stars", her former co-star Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage o ...

deemed her "the complete victim of ballyhoo and sensation", and '' Bus Stop'' director Joshua Logan

Joshua Lockwood Logan III (October 5, 1908 – July 12, 1988) was an American director, writer, and actor. He shared a Pulitzer Prize for co-writing the musical ''South Pacific'' and was involved in writing other musicals.

Early years

Logan wa ...

stated that she was "one of the most unappreciated people in the world".

Monroe's funeral was held on August 8 at the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, where her foster parents Ana Lower and Grace McKee Goddard had also been buried. The service was arranged by her former husband Joe DiMaggio, her half-sister Berniece Baker Miracle and her business manager Inez Melson, who decided to invite only around thirty of her closest family members and friends, excluding most of Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywoo ...

. Police were present to keep the press away and to control the several hundred spectators who crowded the streets around the cemetery.

The funeral service, presided over by a local minister, was conducted at the cemetery's chapel. Monroe was laid out in a green Emilio Pucci

Don Emilio Pucci, Marchese di Barsento (; 20 November 1914 – 29 November 1992) was an Italian aristocrat, fashion designer and politician. He and his eponymous company are synonymous with geometric prints in a kaleidoscope of colors.

Earl ...

dress and held a bouquet of small pink roses. Her longtime make-up artist and friend, Whitey Snyder, had done her make-up. The eulogy was delivered by Lee Strasberg

Lee Strasberg (born Israel Strassberg; November 17, 1901 – February 17, 1982) was an American theatre director, actor and acting teacher. He co-founded, with theatre directors Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford, the Group Theatre in 193 ...

, and a selection from Tchaikovsky

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky , group=n ( ; 7 May 1840 – 6 November 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He wrote some of the most pop ...

's '' Sixth Symphony'' as well as a record of Judy Garland

Judy Garland (born Frances Ethel Gumm; June 10, 1922June 22, 1969) was an American actress and singer. While critically acclaimed for many different roles throughout her career, she is widely known for playing the part of Dorothy Gale in ''The ...

singing " Over the Rainbow" were played. Monroe was interred at crypt No. 24 at the Corridor of Memories. DiMaggio arranged for red roses to be placed in a vase attached to the crypt three times a week for the next twenty years.

In 1992, Hugh Hefner

Hugh Marston Hefner (April 9, 1926 – September 27, 2017) was an American magazine publisher. He was the founder and editor-in-chief of ''Playboy'' magazine, a publication with revealing photographs and articles which provoked charges of obsc ...

paid $75,000 to be interred at Westwood Memorial Park, in the crypt beside Monroe's. In 2009, he said to the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'': "Spending eternity next to Marilyn is an opportunity too sweet to pass up."

Administration of estate

In her will, Monroe left several thousand dollars to her half-sister Berniece Baker Miracle and her secretary May Reis, a share for the education of her friendNorman Rosten

Norman Rosten (January 1, 1913 – March 7, 1995) was an American poet, playwright, and novelist.

Life

Rosten was born to a Polish Jewish family in New York City and grew up in Hurleyville, New York. He was graduated from Brooklyn College and N ...

's daughter, and established a $100,000 trust fund

A trust is a legal relationship in which the holder of a right gives it to another person or entity who must keep and use it solely for another's benefit. In the Anglo-American common law, the party who entrusts the right is known as the "settl ...

to cover the costs of the care of her mother, Gladys Pearl Baker, and the widow of her acting teacher Michael Chekhov

Mikhail Aleksandrovich Chekhov (russian: Михаил Александрович Чехов; 29 August 1891 – 30 September 1955), known as Michael Chekhov, was an American actor, director, author and theatre practitioner. He was a nephew ...

. From the remaining estate she granted twenty-five percent to her former psychiatrist Marianne Kris "for the furtherance of the work of such psychiatric institutions or groups as she shall elect", and seventy-five percent, including her personal effects, film royalties and real estate, to Lee Strasberg, whom she instructed to distribute her effects "among my friends, colleagues and those to whom I am devoted". Due to legal complications, the beneficiaries were not paid until 1971.

When Strasberg died in 1982, his estate was willed to his widow Anna, who claimed Monroe's publicity rights and began to license her image to companies. In 1990, she unsuccessfully sued the Anna Freud Centre

The Anna Freud Centre (now renamed the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families) is a child mental health research, training and treatment centre located in London, United Kingdom. The Centre aims to transform current mental health ...

, to which Kris had bequeathed her Monroe rights, in an attempt to gain full rights to Monroe's estate. In 1996, Anna Strasberg hired CMG Worldwide, a celebrity-legacy licensing group, to manage the licensing rights.

Anna Strasberg went on to prevent Odyssey Group, Inc. from auctioning effects that Monroe's business manager Inez Melson, who had also been named Monroe's special administrator of estate, handed down to her nephew, Millington Conroy. Between 1996 and 2001, CMG entered into 700 licensing agreements with merchandisers. Against Monroe's wishes, Lee Strasberg had never distributed her effects amongst her friends, and in 1999 Anna commissioned Christie's

Christie's is a British auction house founded in 1766 by James Christie. Its main premises are on King Street, St James's in London, at Rockefeller Center in New York City and at Alexandra House in Hong Kong. It is owned by Groupe Artémis, t ...

to auction them, netting $13.4 million. In 2000, she founded Marilyn Monroe LLC

A limited liability company (LLC for short) is the US-specific form of a private limited company. It is a business structure that can combine the pass-through taxation of a partnership or sole proprietorship with the limited liability of a ...

.

Marilyn Monroe LLC's claim to exclusive ownership of Monroe's publicity rights became subject to a "landmark egalcase" in 2006, when the heirs of three freelance photographers who had photographed her—Sam Shaw, Milton Greene, and Tom Kelley—successfully challenged the company in courts in California and New York State. In May 2007, the courts determined that Monroe could not have passed her publicity rights to her estate, as the first law granting such right, the California Celebrities Rights Act

The Celebrities Rights Act or Celebrity Rights Act was passed in California in 1985, which enabled a celebrity's personality rights to survive his or her death. Previously, the 1979 ''Lugosi v. Universal Pictures'' decision by the California Suprem ...

, was not passed until 1985.

Monroe's estate terminated their business relationship with CMG Worldwide in 2010, and sold the licensing rights to Authentic Brands Group

Authentic Brands Group LLC (ABG) is an American brand management company headquartered in New York City. Its holdings include various apparel, athletics, and entertainment brands, for which it partners with other companies to license and merchand ...

the following year. Also in 2010, the estate sold Monroe's Brentwood home for $3.8 million, and published a selection of her private notes, diaries and correspondence as a book called ''Fragments: Poems, Intimate Notes, Letters''.

Conspiracy theories

1960s: Frank A. Capell, Jack Clemmons

During the 1960s, there were no widespread conspiracy theories about Monroe's death. The first allegations that she had been murdered originated in anti-communist activistFrank A. Capell

Francis Alphonse Capell (May 8, 1907 – October 18, 1980), was a conservative, anticommunist writer, and essayist. He was the publisher of the newsletter ''Herald of Freedom'' in Zarephath, New Jersey. He was one of the first writers to spe ...

's self-published pamphlet ''The Strange Death of Marilyn Monroe'' (1964), in which he claimed that her death was part of a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

conspiracy. Capell claimed that Monroe and U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

Robert F. Kennedy had an affair, which she took too seriously and was threatening to cause a scandal; Kennedy therefore ordered her to be assassinated to protect his career. In addition to accusing Kennedy of being a communist sympathizer, Capell also claimed that many other people close to Monroe, such as her doctors and ex-husband Arthur Miller

Arthur Asher Miller (October 17, 1915 – February 10, 2005) was an American playwright, essayist and screenwriter in the 20th-century American theater. Among his most popular plays are ''All My Sons'' (1947), ''Death of a Salesman'' (19 ...

, were communists.

Capell's credibility has been seriously questioned because his only source was columnist

Capell's credibility has been seriously questioned because his only source was columnist Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and c ...

, who in turn had received much of his information from him; Capell, therefore, was citing himself. Capell's friend, LAPD Sergeant Jack Clemmons, aided him in developing his pamphlet; Clemmons, who was the first police officer on the scene of Monroe's death, became a central source for conspiracy theorists. He later made claims that he had not mentioned in the official 1962 investigation: he alleged that when he arrived at Monroe's house, Eunice Murray was washing her sheets in the laundry, and he had "a sixth sense" that something was wrong.

Capell and Clemmons' allegations have been linked to their political goals. Capell dedicated his life to revealing an "International Communist Conspiracy" and Clemmons was a member of The Police and Fire Research Organization (FiPo), which sought to expose "subversive activities which threaten our American way of life". FiPo and similar organizations were known for their stance against the Kennedys and for sending the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI) letters incriminating them; a 1964 FBI file that speculated on an affair between Monroe and Robert F. Kennedy is likely to have come from them. Furthermore, Capell, Clemmons, and a third person were indicted in 1965 by a California grand jury for "conspiracy to libel by obtaining and distributing a false affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or '' deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by law. Such a statemen ...

" claiming that Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the e ...

Thomas Kuchel had once been arrested for a homosexual act. They had done this because Kuchel had supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration req ...

. Capell pleaded guilty, and charges against Clemmons were dropped after he resigned from the LAPD.

In the 1960s, Monroe's death was also discussed in Charles Hamblett's ''Who Killed Marilyn Monroe?'' (1966) and in James A. Hudson's ''The Mysterious Death of Marilyn Monroe'' (1968). Neither Capell's, Hamblett's, or Hudson's accounts were widely disseminated.

1970s: Norman Mailer, Robert Slatzer, Anthony Scaduto

The allegations of murder first became part of mainstream discussion with the publication ofNorman Mailer

Nachem Malech Mailer (January 31, 1923 – November 10, 2007), known by his pen name Norman Kingsley Mailer, was an American novelist, journalist, essayist, playwright, activist, filmmaker and actor. In a career spanning over six decades, Mailer ...

's '' Marilyn: A Biography'' in 1973. Despite not having any evidence, Mailer repeated the claim that Monroe and Robert F. Kennedy had an affair and speculated that she was killed by either the FBI or the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

(CIA), who wished to use the murder as a "point of pressure ... against the Kennedys". The book was heavily criticized in reviews, and later that year Mailer recanted his allegations in an interview with Mike Wallace

Myron Leon Wallace (May 9, 1918 – April 7, 2012) was an American journalist, game show host, actor, and media personality. He interviewed a wide range of prominent newsmakers during his seven-decade career. He was one of the original correspo ...

for ''60 Minutes

''60 Minutes'' is an American television news magazine broadcast on the CBS television network. Debuting in 1968, the program was created by Don Hewitt and Bill Leonard, who chose to set it apart from other news programs by using a unique st ...

'', stating that he had made them to ensure commercial success for his book, and that he believes Monroe's death was "ten to one" an "accidental suicide".

Two years later, Robert F. Slatzer published ''The Life and Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe'' (1975), based on Capell's pamphlet. In addition to his assertion that Monroe was killed by Robert F. Kennedy, Slatzer also controversially claimed to have been married to Monroe in Mexico for three days in October 1952, and that they had remained close friends until her death. Although his account was not widely circulated at the time, it has remained central to conspiracy theories.

In October 1975, rock journalist Anthony Scaduto

Anthony Scaduto (March 7, 1932 – December 12, 2017) was an American journalist and biographer of rock musicians, who also wrote under the name Tony Sciacca. His most famous work is ''Dylan'', a biography of Bob Dylan, first published in 1972. It ...

published an article about Monroe's death in soft porn magazine ''Oui'', and the following year expanded his account into book form as ''Who Killed Marilyn Monroe?'' (1976), published under the pen name Tony Sciacca. His only sources were Slatzer and his private investigator, Milo Speriglio. In addition to repeating Slatzer's claims, Scaduto alleged that Monroe had kept a red diary in which she had written confidential political information she had heard from the Kennedys, and that her house had been wiretapped by surveillance expert Bernard Spindel on the orders of union leader Jimmy Hoffa

James Riddle Hoffa (born February 14, 1913 – disappeared July 30, 1975; declared dead July 30, 1982) was an American labor union leader who served as the president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) from 1957 until 1971.

F ...

, who was hoping to obtain incriminating evidence he could use against the Kennedys.

1980s: Milo Speriglio, Anthony Summers

In 1982, Speriglio published ''Marilyn Monroe: Murder Cover-Up'', in which he claimed that Monroe had been murdered by Hoffa and mob bossSam Giancana

Salvatore Mooney Giancana (; born Gilormo Giangana; ; May 24, 1908 – June 19, 1975) was an American mobster who was boss of the Chicago Outfit from 1957 to 1966.

Giancana was born in Chicago to Italian immigrant parents. He joined the 42 ...

. Basing his account on Slatzer and Scaduto's books, Speriglio added statements made by Lionel Grandison, who worked at the Los Angeles County coroner's office at the time of Monroe's death. Grandison claimed that Monroe's body had been extensively bruised but this had been omitted from the autopsy report, and that he had seen the "red diary", but it had mysteriously disappeared.

Speriglio and Slatzer demanded that the investigation into Monroe's death be re-opened by authorities, and the Los Angeles District Attorney agreed to review the case. The new investigation could not find any evidence to support the murder claims. Grandison was found not to be a reliable witness as he had been fired from the coroner's office for stealing from corpses. The allegations that Monroe's home was wiretapped by Spindel were also found to be false. Spindel's apartment had been raided by the Manhattan District Attorney

The New York County District Attorney, also known as the Manhattan District Attorney, is the elected district attorney for New York County (Manhattan), New York. The office is responsible for the prosecution of violations of New York state laws ...

's office in 1966, during which his tapes were seized. He later made a claim that he had wiretapped Monroe's house, but it was not supported by the contents of the tapes, to which the investigators had listened.

The most prominent Monroe conspiracy theorist in the 1980s was British journalist Anthony Summers, who claimed that Monroe's death was an accidental overdose enabled and covered up by Robert F. Kennedy. His book, ''Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe'' (1985), became one of the most commercially successful Monroe biographies. Prior to writing on Monroe, he had authored a book on a conspiracy theory of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. His investigation on Monroe began as an assignment for the British tabloid the ''

The most prominent Monroe conspiracy theorist in the 1980s was British journalist Anthony Summers, who claimed that Monroe's death was an accidental overdose enabled and covered up by Robert F. Kennedy. His book, ''Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe'' (1985), became one of the most commercially successful Monroe biographies. Prior to writing on Monroe, he had authored a book on a conspiracy theory of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. His investigation on Monroe began as an assignment for the British tabloid the ''Sunday Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet ...

'' to cover the Los Angeles District Attorney's 1982 review.

According to Summers, Monroe had severe substance abuse problems and was psychotic

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior ...

in the last months of her life. He alleges that Monroe had affairs with both John and Robert Kennedy, and that when Robert ended their affair she threatened to reveal their association. Kennedy and Peter Lawford attempted to prevent this by enabling her addictions. According to Summers, Monroe became hysterical and accidentally overdosed, dying in an ambulance on the way to the hospital. Kennedy wanted to leave Los Angeles before Monroe's death became public to avoid being associated with it, and therefore her body was returned to Helena Drive and the overdose staged as a suicide by Lawford, the Kennedys and J. Edgar Hoover.

Summers based his account on interviews he had conducted with 650 people connected to Monroe, but his research has been criticized by biographers Donald Spoto and Sarah Churchwell. According to Spoto, Summers contradicts himself, presents false information as fact, and misrepresents what some of Monroe's friends said about her. Churchwell, meanwhile, has stated that while Summers accumulated a large collection of anecdotal material, most of his allegations are speculation; many of the people he interviewed could provide only second- or third-hand accounts, and they "relate what they believe, not what they demonstrably know". Summers was also the first major biographer to find Slatzer a credible witness, and relies heavily on testimonies by other controversial witnesses, including Jack Clemmons and Jeanne Carmen

Jeanne Laverne Carmen (August 4, 1930 – December 20, 2007) was an American model, actress and trick-shot golfer.

Early life and career

Carmen was born in Paragould, Arkansas. As a child, she picked cotton before running away from home at ...

, a model-actress whose claim to have been Monroe's close friend has been disputed by Spoto and Lois Banner.

Summers' allegations formed the basis for the BBC documentary ''Marilyn: Say Goodbye to the President'' (1985), and for a 26-minute segment produced for ABC's '' 20/20''. The ''20/20'' segment was never aired, as ABC President Roone Arledge

Roone Pinckney Arledge Jr. (July 8, 1931 – December 5, 2002) was an American sports and news broadcasting executive who was president of ABC Sports from 1968 until 1986 and ABC News from 1977 until 1998, and a key part of the company's rise ...

decided that the claims made in it required more evidence to back them up. Summers claimed that Arledge's decision was influenced by pressure from the Kennedy family.

1990s: Brown and Barham, Donald H. Wolfe, Donald Spoto

In the 1990s, two new books alleged that Monroe was murdered: Peter Brown and Patte Barham's ''Marilyn: The Last Take'' (1992) and Donald H. Wolfe's ''The Last Days of Marilyn Monroe'' (1998). Neither presented much new evidence but relied extensively on Capell and Summers as well as on discredited witnesses such as Grandison, Slatzer, Clemmons, and Carmen; Wolfe also did not provide any sources for many of his claims and disregarded many of the findings of the autopsy without explanation. In his 1993 biography of Monroe, Donald Spoto disputed the previous conspiracy theories but alleged that Monroe's death was an accidental overdose staged as a suicide. According to him, her doctors Greenson (psychiatrist) and Engelberg (personal physician) had been trying to stop her abuse of Nembutal. In order to monitor her drug use, they had agreed to never prescribe her anything without first consulting with each other. Monroe was able to persuade Engelberg to break his promise by lying to him that Greenson had agreed to it. She took several Nembutals on August 4, but did not tell this to Greenson, who prescribed her a chloral hydrate enema; the combination of these two drugs killed her. Afraid of the consequences, the doctors and Eunice Murray then staged the death as a suicide. Spoto argued that Monroe could not have been suicidal because she had reached a new agreement with Fox and because she was allegedly going to remarry Joe DiMaggio. He based his theory of her death on alleged discrepancies in the police statements given by Monroe's housekeeper and doctors, a claim made by Monroe's publicist Arthur P. Jacobs's wife that he had been alerted of the death already at 10:30 p.m., as well as on claims made by prosecutor John Miner, who was involved in the official investigation. Miner had alleged that her autopsy revealed signs more consistent with anenema

An enema, also known as a clyster, is an injection of fluid into the lower bowel by way of the rectum.Cullingworth, ''A Manual of Nursing, Medical and Surgical'':155 The word enema can also refer to the liquid injected, as well as to a devic ...

than oral ingestion.

2000s: John Miner, Matthew Smith

Miner's allegations that Monroe's death was not a suicide received more publicity in the 2000s, when he published transcripts that he claimed to have made from audiotapes that Monroe recorded shortly before her death. Miner claimed that Monroe gave the tapes to Greenson, who invited him to listen to them after her death. On the tapes, Monroe spoke of her plans for the future, which Miner argues is proof that she could not have killed herself. She also discussed her sex life and use of enemas; Miner alleged that Monroe was killed by an enema that was administered by Murray. Miner's allegations have received criticism. During the official review of the case by the district attorney in 1982, he told the investigators about the tapes, but did not mention that he had transcripts of them. Miner claimed that this was because Greenson had sworn him to silence. The tapes themselves have never been found, and Miner remains the only person to claim they existed. Greenson was already dead before Miner went public with them. Biographer Lois Banner knew Miner personally because they both worked at theUniversity of Southern California

, mottoeng = "Let whoever earns the palm bear it"

, religious_affiliation = Nonsectarian—historically Methodist

, established =

, accreditation = WSCUC

, type = Private research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $8. ...

; she further challenged the authenticity of the transcripts. Miner had once lost his license to practice law for several years, lied to Banner about having worked for the Kinsey Institute

The Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction (often shortened to The Kinsey Institute) is a research institute at Indiana University. Established in Bloomington, Indiana, in 1947 as a nonprofit, the institute merged with Indi ...

, and had gone bankrupt shortly before selling the alleged transcripts. He had first attempted to sell the transcripts to '' Vanity Fair'', but when the magazine had asked him to show them to Summers in order to validate them, it had become apparent that he did not have them.

The transcripts, which Miner sold to British author Matthew Smith, were therefore written several decades after he alleged to have listened to the tapes. Miner's claim that Monroe's housekeeper was in fact her nurse and administered her enemas on a regular basis is also not supported by evidence. Furthermore, Banner wrote that Miner had a personal obsession about enemas and practiced sadomasochism

Sadomasochism ( ) is the giving and receiving of pleasure from acts involving the receipt or infliction of pain or humiliation. Practitioners of sadomasochism may seek sexual pleasure from their acts. While the terms sadist and masochist refer ...

; she concluded that his theory about Monroe's death "represented his sexual interests" and was not based on evidence.

Smith published the transcripts as part of his book ''Victim: The Secret Tapes of Marilyn Monroe'' (2003). He asserted that Monroe was murdered by the CIA due to her association with Robert F. Kennedy, as the agency wanted revenge for the Kennedys' handling of the Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (, sometimes called ''Invasión de Playa Girón'' or ''Batalla de Playa Girón'' after the Playa Girón) was a failed military landing operation on the southwestern coast of Cuba in 1961 by Cuban exiles, covertly f ...

. Smith had already written about the topic in his previous book, ''The Men Who Murdered Marilyn'' (1996). Noting that Smith included no footnotes in his 1996 book and only eight in ''Victim'', Churchwell has called his account "a tissue of conjecture, speculation and pure fiction as documentary fact" and "arguably the least factual of all Marilyn lives". The Miner transcripts were also discussed in a 2005 ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

'' article.

Notes

References

Footnotes

Sources

* * * * * * * * *External links

"Marilyn Monroe Dead, Pills Near"

Articles of Monroe's death in ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''

"From the Archives: Marilyn Monroe Dies; Pills Blamed"

in ''

Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the ...

''

"Funeral for a Hollywood legend: The death of Marilyn Monroe

in ''Los Angeles Times''

"Marilyn Monroe Is Dead"

in ''

Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

''

"Marilyn is Dead

Obituary in ''

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide ...

''

"Death of Marilyn Monroe"

A ''

British Pathé

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

'' newsreel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Death Of Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe

1962 in California

1962 in Los Angeles

Monroe, Marilyn

Monroe, Marilyn

August 1962 events in the United States

Conspiracy theories in the United States