death by sawing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Death by sawing is the act of sawing or cutting a living person in half, either sagittally (usually midsagittally), or transversely. Death by sawing was a method of execution reportedly used in different parts of the world.

Death by sawing is the act of sawing or cutting a living person in half, either sagittally (usually midsagittally), or transversely. Death by sawing was a method of execution reportedly used in different parts of the world.

pp.167–70

/ref> In only one case, the story about

p.631

/ref> In other cases where details about the method beyond the mere sawing act are explicitly supplied, the condemned person was apparently fastened to either one or two boards prior to sawing.

p.368

/ref> One tradition states that he was put within a tree, and then sawn apart; another says he was sawn apart by means of a wooden saw.

Several early Christians are credited with being martyred by means of a saw. The earliest, and most famous, is the obscure apostle of

Several early Christians are credited with being martyred by means of a saw. The earliest, and most famous, is the obscure apostle of

p.46

/ref> In the following, the tale as told by Busnot will be given. Melec was judged as the chief rebel to be punished in a rebellion instigated by one of the Sultan's sons, Mulay Muhammad. In particular, according to Busnot, the Sultaness was incensed that Melec had personally beheaded one of her cousins, Ali Bouchasra. In September/October 1705, Mulay Ismail sent for his chief carpenter and asked if his saws were capable of sawing a man in two. The carpenter answered "Sure enough". He was then given the grisly task, and before he left, he asked him whether Melec should be sawn across or along the length. The emperor said the sawing should proceed lengthwise, from the head downwards. He told, however, Boachasra's sons, they should follow the carpenter and decide for themselves how best to take revenge upon the murderer (i.e., Melec) of their father. Taking with him 8 of the public executioner's assistants, the master carpenter went to the prison where Melec was held, two of his brand new saws packed in cloth, in order to keep from Melec information of the intended manner of execution. Melec was now placed on a mule, bound with an iron chain, and led to the public square, where some 4000 of his relatives and members of his tribe were assembled. These made a "terrifying" spectacle through screaming, and clawing their faces in a public display of grief. Melec, on the other hand, seemed unperturbed, calmly smoking from his tobacco pipe. When taken down from the mule, Melec's clothes were removed, damning letters "proving" his treason was cast in the fire. Then, he was strapped onto a board, and placed upon a saw-bench, his arms and legs fastened. The executioner's team then sought to start by sawing him from the head downwards, but Boucasra's sons intervened, and demanded that one began between Melec's legs instead, because otherwise, he would die too quickly. Under the terrible screams of Melec and his relatives, thus began his execution. Once they had sawn him up to the

The Sikh

The Sikh

p.453

/ref>

Methods

Different methods of death by sawing have been recorded. In cases related to the Roman EmperorCaligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

, the sawing is said to be through the middle ( transversely).''Scott'' (1995), p.142 In the cases of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, it is stated that the sawing was lengthwise, both from the groin upwards and from the skull downwards ( midsagittally).''Busnot'' (1717)pp.167–70

/ref> In only one case, the story about

Simon the Zealot

Simon the Zealot (, ) or Simon the Canaanite or Simon the Canaanean (, ; grc-gre, Σίμων ὁ Κανανίτης; cop, ⲥⲓⲙⲱⲛ ⲡⲓ-ⲕⲁⲛⲁⲛⲉⲟⲥ; syc, ܫܡܥܘܢ ܩܢܢܝܐ) was one of the most obscure among the apostl ...

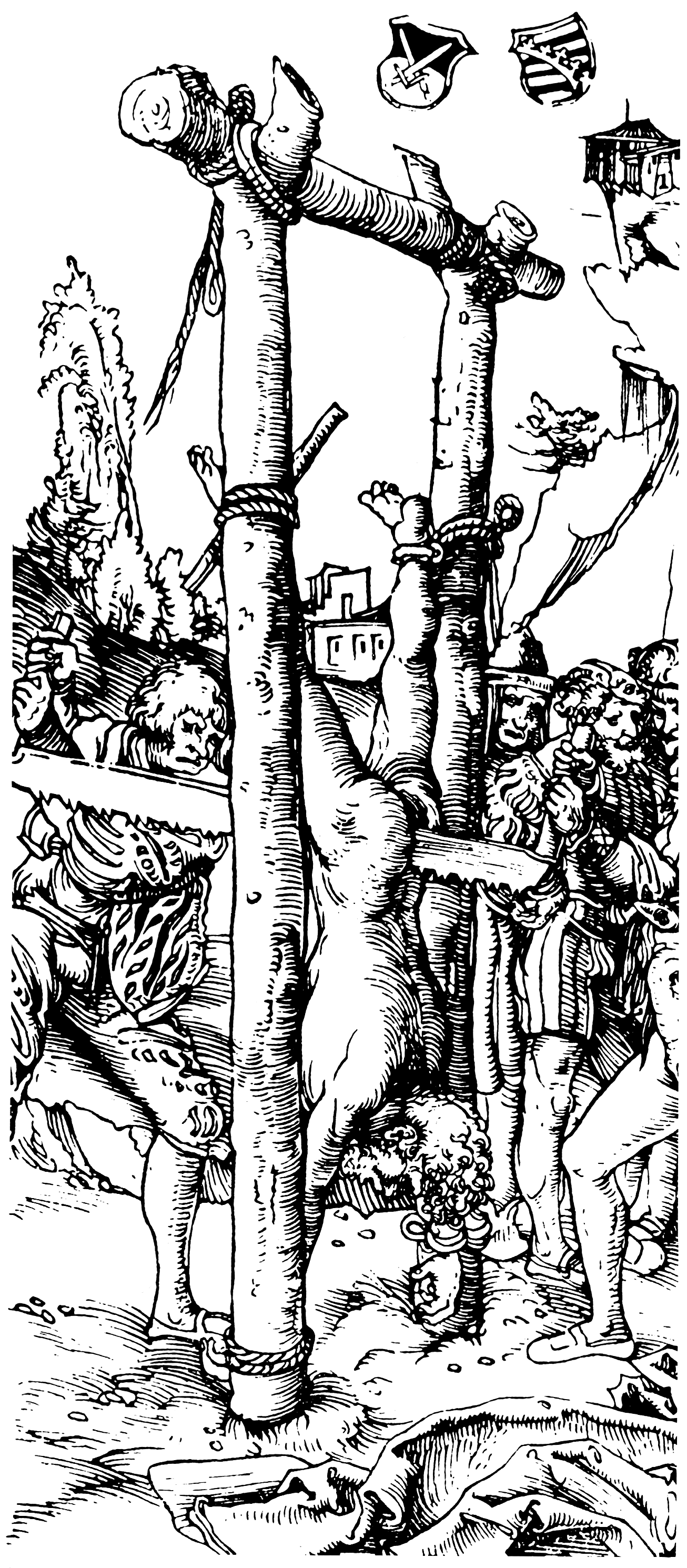

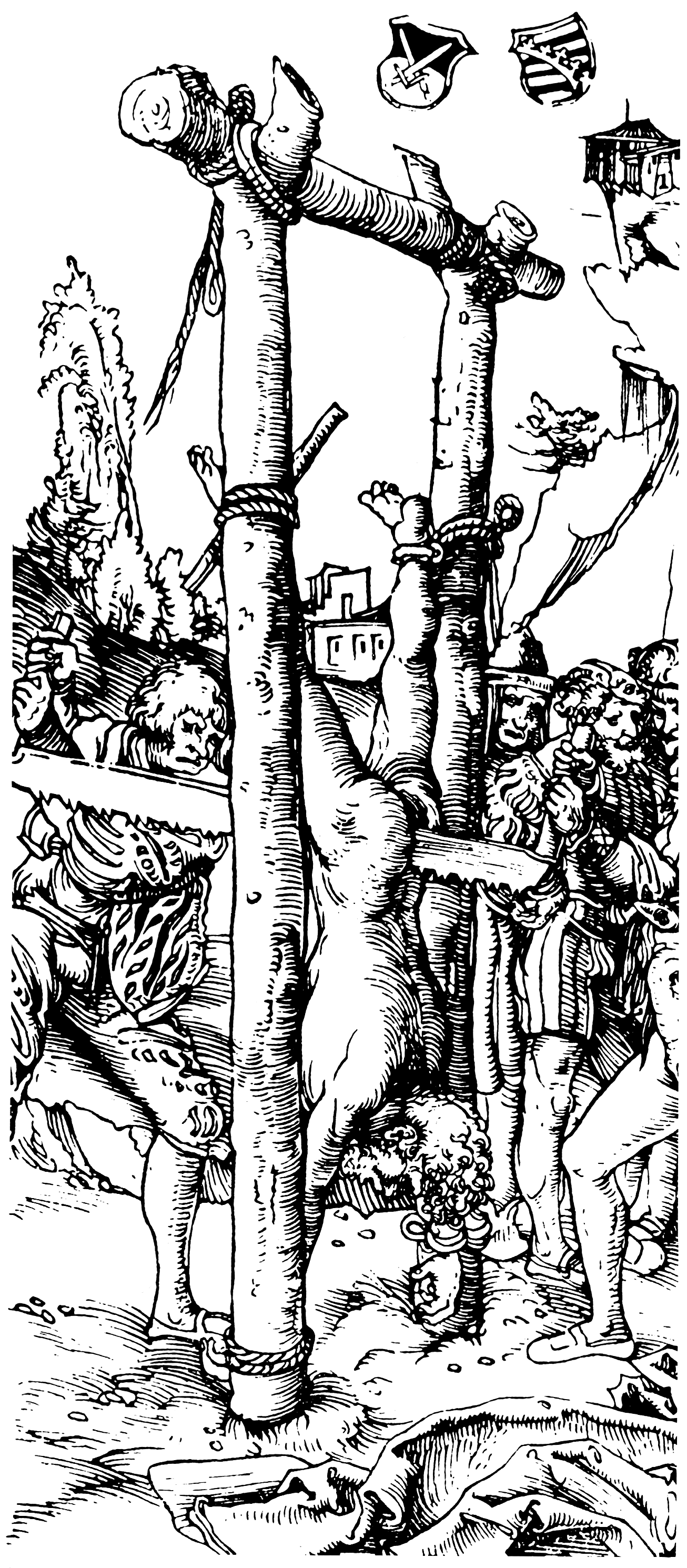

, the person is explicitly described as being hung upside-down and sawn apart vertically through the middle, starting at the groin, with no mention of fastenings or support boards around the person, in the manner depicted in illustrations.''Geyer'' (1738p.631

/ref> In other cases where details about the method beyond the mere sawing act are explicitly supplied, the condemned person was apparently fastened to either one or two boards prior to sawing.

Ancient history and classical antiquity

Ancient Persia

;The legend of JamshidJamshid

Jamshid () ( fa, جمشید, ''Jamshīd''; Middle- and New Persian: جم, ''Jam'') also known as ''Yima'' (Avestan: 𐬫𐬌𐬨𐬀 ''Yima''; Pashto/Dari: یما ''Yama'') is the fourth Shah of the mythological Pishdadian dynasty of Iran acco ...

was a legendary shah

Shah (; fa, شاه, , ) is a royal title that was historically used by the leading figures of Iranian monarchies.Yarshater, EhsaPersia or Iran, Persian or Farsi, ''Iranian Studies'', vol. XXII no. 1 (1989) It was also used by a variety of ...

of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, whose story is told in the ''Shahnameh

The ''Shahnameh'' or ''Shahnama'' ( fa, شاهنامه, Šāhnāme, lit=The Book of Kings, ) is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran. Consisting of some 50,00 ...

'' by Ferdowsi

Abul-Qâsem Ferdowsi Tusi ( fa, ; 940 – 1019/1025 CE), also Firdawsi or Ferdowsi (), was a Persians, Persian poet and the author of ''Shahnameh'' ("Book of Kings"), which is one of the world's longest epic poetry, epic poems created by a sin ...

. After 300 years of blessed reign, Jamshid forgot the blessings came from God, and began demanding that he be revered as a god himself. The people rebelled, and Zahhak

Zahhāk or Zahāk () ( fa, ضحّاک), also known as Zahhak the Snake Shoulder ( fa, ضحاک ماردوش, Zahhāk-e Mārdoush), is an evil figure in Persian mythology, evident in ancient Persian folklore as Azhi Dahāka ( fa, اژی دهاک) ...

had him sawn asunder.

; Parysatis

Parysatis

Parysatis (; peo, Parušyātiš, grc, Παρύσατις; 5th-century BC) was a powerful Persian Queen, consort of Darius II and had a large influence during the reign of Artaxerxes II.

Biography

Parysatis was the daughter of Artaxerxes I, Em ...

, wife and half-sister of Darius II

Darius II ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ), also known by his given name Ochus ( ), was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 423 BC to 405 or 404 BC.

Artaxerxes I, who died in 424 BC, was followed by h ...

(r. 423–405 BC) was the real power behind the throne of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

; she instigated and became involved in a number of court intrigues, made several enemies, yet had an uncanny knack for dispatching them at an opportune time. At one point, she decided to have the siblings of her daughter-in-law Stateira killed, and only relented from killing Stateira as well due to the desperate pleas of her son, Artaxerxes II. Stateira's sister Roxana was the first of her siblings to be killed, by being sawn in half. When Darius II died, Parysatis moved quickly, and was able to have the new queen Stateira poisoned; Parysatis still remained a power to be reckoned with for years after.

;Hormizd IV

Hormizd IV

Hormizd IV (also spelled Hormozd IV or Ohrmazd IV; pal, 𐭠𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭬𐭦𐭣) was the Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from 579 to 590. He was the son and successor of Khosrow I () and his mother was a Khazar princess.

During his reign, Ho ...

( fa, هرمز چهارم), son of Khosrow I

Khosrow I (also spelled Khosrau, Khusro or Chosroes; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩; New Persian: []), traditionally known by his epithet of Anushirvan ( [] "the Immortal Soul"), was the Sasanian Empire, Sasanian King of Kings of Iran from ...

, was the twenty-first Sasanian Empire, King of Persia from AD 579 to 590. He was deeply resented by the nobility due to his cruelties. In 590, a palace coup was staged in which his son, Khosrow II

Khosrow II (spelled Chosroes II in classical sources; pal, 𐭧𐭥𐭮𐭫𐭥𐭣𐭩, Husrō), also known as Khosrow Parviz (New Persian: , "Khosrow the Victorious"), is considered to be the last great Sasanian king (shah) of Iran, ruling fr ...

, was declared king. Hormizd was forced to watch his wife and one of his sons sawn in two, and the deposed king was then blinded. After a few days, the new king is said to have killed his father in a fit of rage.

Thracians

Thracians

The Thracians (; grc, Θρᾷκες ''Thrāikes''; la, Thraci) were an Indo-European languages, Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe in ancient history.. ...

were regarded as warlike, ferocious, and bloodthirsty by Romans and Greeks. One of the most notorious was the king Diegylis

Diegylis (Ancient Greek: Διήγυλις) was a chieftain of the Thracian Caeni tribe and father of Ziselmius. He is described by ancient sources (such as Diodorus Siculus) as extremely bloodthirsty.Diodorus Siculus, ''Bibliotheca historica'', ...

, possibly only topped by his son Ziselmius

Ziselmius, or Zibelmius or Zisemis (Ancient Greek: Ζισέλμιος) was a chieftain of the Thracian Caeni tribe and son of Diegylis.

References

See also

*List of Thracian tribes

This is a list of ancient tribes in Thrace and Dacia ( grc ...

. According to Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

, Ziselmius sawed several people to death and commanded their families to eat the flesh of their murdered relatives. The Thracians eventually rebelled, captured him and sought to inflict every conceivable torture upon him prior to his death.

Ancient Rome

;The Twelve Tables Promulgated about 451 BC, the Twelve Tables is the oldest extant law code for the Romans.Aulus Gellius

Aulus Gellius (c. 125after 180 AD) was a Roman author and grammarian, who was probably born and certainly brought up in Rome. He was educated in Athens, after which he returned to Rome. He is famous for his ''Attic Nights'', a commonplace book, or ...

, whose work "Attic Nights" is partially preserved, states that death by the saw was mentioned for some offenses in the tables, but that the use of which was so infrequent that no one could remember ever having seen it done. Of the retained laws in the Twelve Tables, the following concerning how creditors should proceed with debtors is found in Table 3, article 6: "On the third market-day they he creditors

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

shall cut pieces. If they shall have cut more or less han their shares it shall be with impunity." The translator notes the ambiguity of the original text, but says that later Roman writers understood this to mean that creditors were allowed to cut their shares from the body of the debtor. If true, that would constitute dismemberment, rather than sawing.

;Caligula

This method of execution was uncommon throughout the time of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. However, it was used extensively during the reign of Caligula

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), better known by his nickname Caligula (), was the third Roman emperor, ruling from 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the popular Roman general Germanicu ...

when the condemned, including members of his own family, were sawn across the torso

The torso or trunk is an anatomical term for the central part, or the core, of the body of many animals (including humans), from which the head, neck, limbs, tail and other appendages extend. The tetrapod torso — including that of a human � ...

rather than lengthwise down the body. It is said that Caligula would watch such executions while he ate, stating that witnessing the suffering acted as an appetiser.

;The Kitos War

The Kitos War occurred 115–117 AD, and was a rebellion by the Jews within the Roman Empire. Major revolts happened several places, and the main source by Cassius Dio

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history on ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

claims that in Cyrene, 220,000 Greeks were massacred by the Jews; in Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

, 240,000. Dio adds that many of the victims were sawn asunder, and that the Jews licked up the blood of the slain, and "twisted the entrails like a girdle about their bodies".

;Valens

In 365 AD, Procopius declared himself emperor, and moved against Valens. He was defeated in battle, and due to the treachery of his two generals Agilonius and Gomoarius

Gomoarius ( la, Gomoarius, Gumoarius; gr, Γομαρίος) was an Alemannic warrior who served in the Roman army.

In 350 AD, under the usurper Vetranio, Gomoarius was a ''tribunus notariorum scutariorum''. In 359 AD he was raised by Constantius ...

(they had been promised they would be "shown favour" by Valens), he was captured. In 366, he was fastened to two trees bent down with force; when the trees were released, Procopius was ripped apart in the manner of the legendary execution of the bandit Sinis. The "favour" Valens showed to Agilonius and Gomoarius was to have them both sawn asunder.

Jewish tradition

;Death of Isaiah The prophetIsaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

was, according to some traditional rabbinic texts, sawn apart on orders of King Manasseh of Judah.''Warnekros'' (1832)p.368

/ref> One tradition states that he was put within a tree, and then sawn apart; another says he was sawn apart by means of a wooden saw.

Christian martyrs

;Simon the Zealot Several early Christians are credited with being martyred by means of a saw. The earliest, and most famous, is the obscure apostle of

Several early Christians are credited with being martyred by means of a saw. The earliest, and most famous, is the obscure apostle of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, Simon the Zealot

Simon the Zealot (, ) or Simon the Canaanite or Simon the Canaanean (, ; grc-gre, Σίμων ὁ Κανανίτης; cop, ⲥⲓⲙⲱⲛ ⲡⲓ-ⲕⲁⲛⲁⲛⲉⲟⲥ; syc, ܫܡܥܘܢ ܩܢܢܝܐ) was one of the most obscure among the apostl ...

. He is said to have been martyred in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, and that the express mode by which he was executed was to be hanged up by the feet, as in the woodcut illustration.

;Conus and his son

According to the '' Acta Sanctorum'', after his wife's death in the age of Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavi ...

, Conus went with his 7-year-old son into a desert. He destroyed several pagan idols in Cogni, Asia Minor (Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

). When caught, he and his son were tortured by starvation and fire, and were finally put to the saw, praying while they died.

;Symphorosa and her seven sons

According to the 16th-century '' Foxe's Book of Martyrs'', Symphorosa

Symphorosa ( it, Sinforosa; died circa AD 138) is venerated as a saint of the Catholic Church. According to tradition, she was martyred with her seven sons at Tibur (present Tivoli, Lazio, Tivoli, Lazio, Italy) toward the end of the reign of the R ...

was a widow with seven sons living in the age of emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

(98-117) or Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

(117–138). Refusing a command to pray at a heathen temple, Symphorosa was scourged, and then thrown in the river Aniene

The Aniene (; la, Aniō), formerly known as the Teverone, is a river in Lazio, Italy. It originates in the Apennines at Trevi nel Lazio and flows westward past Subiaco, Vicovaro, and Tivoli to join the Tiber in northern Rome. It formed the pr ...

with a large stone fastened to her. The six eldest sons were all killed by stab wounds, and the youngest, Eugenius, was sawn apart.

; The 38 monks and martyrs on Mount Sinai

According to the '' Martyrologium Romanum'', during the reign of Diocletian

Diocletian (; la, Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus, grc, Διοκλητιανός, Diokletianós; c. 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed ''Iovius'', was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Gaius Valerius Diocles ...

"wild barbarians" decided to rob a community of monks living at Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

. There was nothing of material wealth there, and in their rage, the Arabs slaughtered them all, several by flaying, others by sawing them with dull saws.

;St. Tarbula

Accused of practising witchcraft and causing the sickness of the wife of the ardently anti-Christian Persian king Shapur II

Shapur II ( pal, 𐭱𐭧𐭯𐭥𐭧𐭥𐭩 ; New Persian: , ''Šāpur'', 309 – 379), also known as Shapur the Great, was the tenth Sasanian King of Kings (Shahanshah) of Iran. The longest-reigning monarch in Iranian history, he reigned fo ...

, Tarbula was condemned and executed by being sawn in half in the year 345.

Africa

Egypt

;The monk from Montepulciano In the 1630s, there are several reports from theLevant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

and Egypt that monks were killed. One of them, Brother Conrad d'Elis Barthelemy, a native of Montepulciano

Montepulciano () is a medieval and Renaissance hill town and ''comune'' in the Italian province of Siena in southern Tuscany. It sits high on a limestone ridge, east of Pienza, southeast of Siena, southeast of Florence, and north of Rome b ...

is said to have been sawn in two, from the head downwards.

; The renegade Coptic governor

Writing in 1843, William Holt Yates speaks of a governor under Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

(r.1801–49), Abd-ur-Rahman Bey, who was said to be particularly cruel and avaricious. He was a renegade Copt, and abused his position to gain hold of wealth. He is even credited with having sawn people in two. Yates further supplies the detail: "This fellow has since been assassinated-report says, with sanction and approval of the Government"

Morocco

;1705 The sawing of Alcaide Melec One of the most notorious cases of sawing as execution is that of the Alcaide (castellan/governor) Melec underSultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

Moulay Ishmael (r. 1672–1727). The fullest description of this execution is found in Dominique Busnot's 1714 work ''Histoire du règne de Mouley Ismael'', although a brief notice of the event can be found in the January 1706 edition of ''Present state of Europe''.''Rhodes'' (1706)p.46

/ref> In the following, the tale as told by Busnot will be given. Melec was judged as the chief rebel to be punished in a rebellion instigated by one of the Sultan's sons, Mulay Muhammad. In particular, according to Busnot, the Sultaness was incensed that Melec had personally beheaded one of her cousins, Ali Bouchasra. In September/October 1705, Mulay Ismail sent for his chief carpenter and asked if his saws were capable of sawing a man in two. The carpenter answered "Sure enough". He was then given the grisly task, and before he left, he asked him whether Melec should be sawn across or along the length. The emperor said the sawing should proceed lengthwise, from the head downwards. He told, however, Boachasra's sons, they should follow the carpenter and decide for themselves how best to take revenge upon the murderer (i.e., Melec) of their father. Taking with him 8 of the public executioner's assistants, the master carpenter went to the prison where Melec was held, two of his brand new saws packed in cloth, in order to keep from Melec information of the intended manner of execution. Melec was now placed on a mule, bound with an iron chain, and led to the public square, where some 4000 of his relatives and members of his tribe were assembled. These made a "terrifying" spectacle through screaming, and clawing their faces in a public display of grief. Melec, on the other hand, seemed unperturbed, calmly smoking from his tobacco pipe. When taken down from the mule, Melec's clothes were removed, damning letters "proving" his treason was cast in the fire. Then, he was strapped onto a board, and placed upon a saw-bench, his arms and legs fastened. The executioner's team then sought to start by sawing him from the head downwards, but Boucasra's sons intervened, and demanded that one began between Melec's legs instead, because otherwise, he would die too quickly. Under the terrible screams of Melec and his relatives, thus began his execution. Once they had sawn him up to the

navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, although ...

, they pulled out the saw in order to commence from the other side. Melec is said to have been still conscious, asking for some water. His friends, though, thought it best to hasten his demise and shorten his sufferings, and the executioners went on, sawing him from skull to navel so he fell apart. In the process, chunks of flesh were ripped out by the saw's teeth, causing blood to splatter everywhere, thus making the execution quite unbearable to watch.

Around 300 other conspirators were impaled alive, and another report states that in addition to these, some other 20 chief conspirators had their arms and legs sawn off, and left to expire in the marketplace.

;1721 The sawing of Larbe Shott

19 July 1721, a noble descended from the Andalusia

Andalusia (, ; es, Andalucía ) is the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community in Peninsular Spain. It is the most populous and the second-largest autonomous community in the country. It is officially recognised as a ...

n Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct or ...

, Larbe Shott was put to the saw. He had spent considerable time at Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

, and one of the crimes imputed to him was to have spent time in Christian kingdoms without his emperor's leave. Furthermore, he had been found guilty of defiling himself with Christian women, and often drunk alcohol. In short, he was charged as an apostate and unbeliever, in addition to being charged with having invited the "Spaniards" to invade Barbary (i.e., treason). They brought him to one of the gates in the city, fastened him between two boards, and sawed him in two, from the skull downwards. After his death, Mulay Ishmael pardoned him, so that his body could be picked up and given a decent burial at least, instead of being eaten by the dogs.

Americas

;Swiss sawing In 1757, a French officer was executed by his men in a mutiny on Cat Island in current-dayMississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. Three of the mutineers were eventually captured and brought to New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

for trial. After conviction, two of the mutineers died on the French wheel. The last mutineer, a Swiss from the Karrer regiment, was allegedly, nailed into a coffin-shaped wooden box, and it was sawn in two with a cross-cut saw. This claim of a Swiss being sawn in two was first made by the French captain and traveller Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Jean Bernard Bossu Jean Bernard Bossu (1720–1792) was a captain in the French navy, adventurer and explorer. He travelled several times to New France, where he explored the regions along the Mississippi.

Life and work

Bossu was born on 1720-9-29 into a family of su ...

in his 1768 ''Nouveaux Voyages aux Indes Occidentales'', translated into English by Johann Reinhold Forster in 1771.

Commenting on Bossu's general reliability in a footnote to his essay ''A Map within an Indian Painting?'', jurist Morris S. Arnold

Morris Sheppard Arnold (born October 8, 1941) is a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and previously was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Weste ...

says the following: "Bossu's books contain a lot of tall tales, so one needs to be cautious about relying on him". Bossu claims that being "sawed asunder" was a traditional Swiss military punishment, and alleges that one Swiss mutineer actually committed suicide to avoid that punishment. Therefore, the one who was allegedly sawn in half had his punishment as governed by Swiss military law, rather than French. An incident from 1741 (in Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

, Canada) shows that at that time, when two Frenchmen and a Swiss were executed, Swiss mercenary troops had been placed under French military law, rather than under Swiss. Furthermore, detailing the recorded executions in the Swiss Canton of Zürich

The canton of Zürich (german: Kanton Zürich ; rm, Chantun Turitg; french: Canton de Zurich; it, Canton Zurigo) is a Swiss canton in the northeastern part of the country. With a population of (as of ), it is the most populous canton in the ...

through the 15th-18th century, Gerold Meyer von Knonau records 1445 executions in total, none of them being through death by sawing.

;Haitian revolution

In August 1791, a great slave revolt broke out at Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

, eventually leading to Haitian independence. In the process, some 4,000 white planters and their family members were massacred. One of the victims was a carpenter by trade, Robert. The rebels decided he "should die in the way of his occupation" and accordingly fastened him between two boards and sawed him apart.

Asia

Levant

;An episode from the Crusades In 1123, Joscelin de Courtenay and Baldwin II were separately ambushed and surprised by a Turkishemir

Emir (; ar, أمير ' ), sometimes transliterated amir, amier, or ameer, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or cerem ...

, Balac, and made prisoners at the castle at Quartapiert. Some 50 Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, ''hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diaspora ...

, bound by oath to Joscelin as Count of Edessa, decided to free their liege lord as well as Baldwin II. Dressed as monks and pedlars, they gained entry in the town where the two nobles were held captive, and managed, through massacre, to take control of the castle. Joscelin slipped out in order to raise a force, while Baldwin II and his nephew Galeran remained behind to hold the castle. Apprised of the capture of the castle, Balac sent quickly a force to recapture it, and Baldwin II saw no possibility of holding it. Graciously, Balac took Baldwin and his nephew merely prisoners. Not so merciful was he towards the Armenians: Several of them were flayed, others buried up to the neck and used as target practice, the rest were sawn apart.

;The Assassins

The Assassins

An assassin is a person who commits targeted murder.

Assassin may also refer to:

Origin of term

* Someone belonging to the medieval Persian Ismaili order of Assassins

Animals and insects

* Assassin bugs, a genus in the family ''Reduviida ...

, a misnomer for the Nizari, an Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

sect, had an independent kingdom in the Levant during the age of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

, and were feared and loathed by Muslims and Christians alike. The Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela

Benjamin of Tudela ( he, בִּנְיָמִין מִטּוּדֶלָה, ; ar, بنيامين التطيلي ''Binyamin al-Tutayli''; Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre, 1130 Castile, 1173) was a medieval Jewish traveler who visited Europe, Asia, an ...

, travelling the region around 1157 notes that the Assassins were reputed to saw in two the kings of other peoples, if they managed to capture them.

Ottoman Empire

A number of accounts exist where theOttomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

are said to have sawn persons in two, most of them said to occur in Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

's reign (1451–81).

;1453 conquest of Constantinople

A number of cruel excesses against the populace of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

is said to have happened in the wake of the taking of the city. according to one rendering of the tale:

;1460 Capture of Mystras

After the last Despot of Morea

The Despotate of the Morea ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μορέως) or Despotate of Mystras ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μυστρᾶ) was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centu ...

, Demetrios Palaiologos

Demetrios Palaiologos or Demetrius Palaeologus ( el, Δημήτριος Παλαιολόγος, Dēmētrios Palaiologos; 1407–1470) was Despot of the Morea together with his brother Thomas from 1449 until the fall of the despotate in 1460. Deme ...

in 1460 switched allegiance to the Turks and gave them entry to Mystras, a tale grew up that the actual castellan

A castellan is the title used in Medieval Europe for an appointed official, a governor of a castle and its surrounding territory referred to as the castellany. The title of ''governor'' is retained in the English prison system, as a remnant o ...

at the castle of Mystras

Mystras or Mistras ( el, Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς), also known in the ''Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mt. Taygetus, nea ...

was ordered sawn in two. This tale was "well known" in later centuries, whatever actual veracity.

;1460 Michael Szilágyi

In 1460, the Hungarian general Michael Szilágyi

Michael Szilágyi de Horogszeg ( hu, horogszegi Szilágyi Mihály; c. 1400 – 1460) was a Hungarian general, Regent of Hungary, Count of Beszterce and Head of Szilágyi–Hunyadi Liga.

Family

He was born in the early 15th century as vice ...

was seized by the Turks, and since he was regarded as a traitor and spy, he was sawn in half at Constantinople.

; 1460-64 campaigns and slaughter in the Morea

In the following years, inhabitants in Greece under the Venetians fought several battles in the Morea. In 1464, for example, a small city is said to have been subdued, and 500 prisoners sent to Constantinople. There, they were put to the saw, according to one account.

;1463 conquest of Mytilene, Lesbos

The Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

s, then stationed at Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, Ρόδος , translit=Ródos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the So ...

, sent several knights to aid in the defence of Mytilene from the Turks. They eventually surrendered, under promise of having their lives spared. Instead, according to some reports, they were sawn asunder. According to Kenneth Meyer Setton

Kenneth Meyer Setton (June 17, 1914 in New Bedford, Massachusetts – February 18, 1995 in Princeton, New Jersey) was an American historian and an expert on the history of medieval Europe, particularly the Crusades.

Early life, education and aw ...

, the sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

had actually promised to spare the heads of some 400 knights, and sawed them in half to keep his oath of not harming the heads.

;1469/1470 conquest of Negroponte

The Triarchy of Negroponte

The Triarchy of Negroponte was a crusader state established on the island of Euboea ( vec, Negroponte) after the partition of the Byzantine Empire following the Fourth Crusade. Partitioned into three baronies (''terzieri'', "thirds") (Chalkis, K ...

, a Crusader state or ''Stato da Màr

The ''Stato da Màr'' or ''Domini da Mar'' () was the name given to the Republic of Venice's maritime and overseas possessions from around 1000 to 1797, including at various times parts of what are now Istria, Dalmatia, Montenegro, Albania, Greec ...

'' under control of the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

, was extinguished by the capture of the city in 1469/1470, and the governor Paolo Erizzo, is said to treacherously to have been ordered sawn in two, after have being promised his life would be spared. The sultan, Mehmed the Conqueror, is said to have cut off the head of Erizzo's daughter by his own hands, because she would not yield to his desires.

;1473 the arsonist at Gallipoli

In 1473, a Sicilian called Anthony, is said to have managed set fire to the sultan's ships at the Sanjak of Gelibolu

The Sanjak of Gelibolu or Gallipoli (Ottoman Turkish: ''Sancak-i/Liva-i Gelibolu'') was a second-level Ottoman province (''sanjak'' or '' liva'') encompassing the Gallipoli Peninsula and a portion of southern Thrace. Gelibolu was the first Ottoma ...

, Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

. After being captured at Negroponte, he was brought before the sultan who asked him what harm had been done to him that he performed such an evil deed? The young man answered that he simply wanted to harm the enemy of Christianity in some glorious way. The sultan is said to have ordered that Anthony should be sawn in two.

;1480 invasion of Otranto

In 1480, the Ottomans, led by Gedik Ahmed Pasha, invaded mainland Italy, occupying Otranto. A general massacre, of disputed magnitude, occurred. Archbishop Stefano Pendinelli

Stefano Pendinelli (also Stefano Argercolo de Pendinellis; 1403 – 11 August 1480) was the Roman Catholic archbishop of Otranto, Italy. He was slain in 1480, along with all his priests, by the Ottoman force that invaded Otranto. He is among th ...

was, by some reports, ordered to be sawn in half.

;1611 revolt of Dionysius the Philosopher

Dionysius the Philosopher

Dionysios Philosophos (Διονύσιος ο Φιλόσοφος, Dionysios the Philosopher) or Skylosophos ( el, Διονύσιος ο Σκυλόσοφος; c. 1541–1611), "the Dog-Philosopher" or "Dogwise" ("skylosophist"), as called by his r ...

led an eventually unsuccessful revolt against the Ottomans, seeking to establish a power base at Ioannina

Ioannina ( el, Ιωάννινα ' ), often called Yannena ( ' ) within Greece, is the capital and largest city of the Ioannina regional unit and of Epirus, an administrative region in north-western Greece. According to the 2011 census, the c ...

. Dionysius was flayed alive, and his skin, stuffed with straw, was sent as a present to the sultan, Ahmed I

Ahmed I ( ota, احمد اول '; tr, I. Ahmed; 18 April 1590 – 22 November 1617) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1603 until his death in 1617. Ahmed's reign is noteworthy for marking the first breach in the Ottoman tradition of royal f ...

, at Constantinople. The other principal conspirators were said to be punished in various ways, some were burnt alive, others impaled, and yet others sawn asunder.

;The mythologized death of Rhigas, the protomartyr of Greek independence

Rigas Feraios (1760–98), was an early Greek patriot, whose struggle for independence of Greece preceded with about 30 years the general uprising known as the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

. His actual manner of death has garnered many tales; Encyclopædia Britannica 1911, for example, states that he was shot in the back. Yet others state that he was strangled. Some 19th century stories report that he was sawn in two. Finally, one source asserts he was beheaded.

Mughal Empire

The Sikh

The Sikh Bhai Mati Das

Bhai Mati Das ( Punjabi: ਭਾਈ ਮਤੀ ਦਾਸ; died 1675) along with his younger brother Bhai Sati Das were martyrs of early Sikh history. Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Dayala, and Bhai Sati Das were executed at a ''kotwali'' (police-station) in ...

, a follower of the 9th guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur was in 1675 AD ordered executed by emperor Aurangzeb

Muhi al-Din Muhammad (; – 3 March 1707), commonly known as ( fa, , lit=Ornament of the Throne) and by his regnal title Alamgir ( fa, , translit=ʿĀlamgīr, lit=Conqueror of the World), was the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling ...

, along with several other prominent Sikhs, including their Guru, because the Guru was resisting the forceful conversion of Kashmiri Pandits into Islam. Bhai Mati Das was sawn in half, the others in different manners.

Burma

Several reports state that even in the 1820s, sawing criminals in two was an occasional punishment in Burma for "certain offences". The criminals were fastened between two planks prior to the sawing. However, this might possibly have been conflated by reports of ''disembowelment

Disembowelment or evisceration is the removal of some or all of the organs of the gastrointestinal tract (the bowels, or viscera), usually through a horizontal incision made across the abdominal area. Disembowelment may result from an accident ...

'', for which eyewitness reports exist.

The Burmese general Maha Bandula

General Maha Bandula ( my, မဟာဗန္ဓုလ ; 6 November 1782 – 1 April 1825) was commander-in-chief of the Royal Burmese Armed Forces from 1821 until his death in 1825 in the First Anglo-Burmese War. Bandula was a k ...

is said to have had one of his high-ranking officers sawn in two, due to some act of disobedience, the person being fastened between two planks for that purpose.

Vietnam

;Martyrdom of Augustin Huy On occasion, a confusion of reports may exist where, for example, performed post-mortem indignities are misinterpreted as the actual manner of execution: In 1839, the governor of Vietnam's Nam Định Province summoned five hundred soldiers to a banquet to pressure them into trampling upon a cross in renunciation of Christianity. Most of the guests complied, but three Catholic soldiers refused. One of theVietnamese Martyrs

The Vietnamese Martyrs (Vietnamese language, Vietnamese: ''Các Thánh Tử đạo Việt Nam''; French language, French: ''Martyrs du Viêt Nam''), also known as the Martyrs of Annam, Martyrs of Tonkin and Cochinchina, Martyrs of Indochina, or An ...

, Augustin Huy, is reported by some sources to have been sawn in two. Others report that he was hacked to death, or cut in two. But, a letter from 1839, just three weeks after the execution 12 June, states that he was beheaded:

Imperial China

;Technique The movement of a saw may cause a body to sway back and forth making the process difficult for the executioners. The Chinese overcame this problem by securing the victim in an upright position between two boards firmly fixed between stakes driven deep into the ground. Two executioners, one at each end of the saw, would saw downwards through the stabilized boards and enclosed victim. Whether sawing as an execution method actually existed, or that cases referred to are garbled accounts of the " slow slicing" method of execution will remain an open question. ;Tang dynasty The emperor Zhaozong of Tang (r. 888–904) is said to have commanded one of his prisoners sawn asunder. ;Qing dynasty When the last emperor of theMing dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

committed suicide in 1644, the new emperor had one of the previous regime's strongest supporters, Chen, said to be viceroy of Canton, sawn in two. However, growing in popularity in his martyrdom, the new regime condemned the execution of Chen, declared him to have been a holy man, and erected a pagoda in Canton for his memory.

Cambodia

;Khmer Rouge Sawing a person in half vertically was one of many execution method used by theKhmer Rouge

The Khmer Rouge (; ; km, ខ្មែរក្រហម, ; ) is the name that was popularly given to members of the Communist Party of Kampuchea (CPK) and by extension to the regime through which the CPK ruled Cambodia between 1975 and 1979. ...

on infamous Tuol Sleng

The Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum ( km, សារមន្ទីរឧក្រិដ្ឋកម្មប្រល័យពូជសាសន៍ទួលស្លែង) or simply Tuol Sleng ( km, ទួលស្លែង, link=no, ; lit. "Hill of ...

prison and killing fields

The Killing Fields ( km, វាលពិឃាត, ) are a number of sites in Cambodia where collectively more than one million people were killed and buried by the Khmer Rouge regime (the Communist Party of Kampuchea) during its rule of t ...

. Guards tied turned up bodies on trees or special poles to saw the Chams, vietnamese, captured foreigners or suspected crades in half. The sawn remains and organs were either left on display to decorate the trees, power poles and buildings tied or impaled on Meat hook or had their organs consumed inside a wine cup.

Europe

Spain

;Morisco revolt In the aftermath of the destruction of the last Islamic kingdom in Spain, Granada in 1492, theMorisco

Moriscos (, ; pt, mouriscos ; Spanish for "Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown commanded to convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed the open p ...

es, the descendants of Muslims and those who still were, in secret, adherents of Islam, felt increasingly persecuted. In 1568, the Morisco revolt broke out, under leadership of Aben Humeya. The crushing of the revolt was extremely bloody, and at Almería

Almería (, , ) is a city and municipality of Spain, located in Andalusia. It is the capital of the province of the same name. It lies on southeastern Iberia on the Mediterranean Sea. Caliph Abd al-Rahman III founded the city in 955. The city gr ...

1569, the historian Luis del Marmol Carvajal

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archai ...

states that one Morisco was sawn apart alive.

;La Mancha rebellion

In the Spanish rebellion of 1808 against the occupying French forces, reports exist that some French officers were sawn in two. In one of those reports, it is colonel Rene (or Frene) who met this fate. In another report, Rene was merely thrown into a kettle of boiling water, whereas the officers Caynier and Vaugien were the ones sawn in two.

Russia

;1812 the ''Grande Armée'' After the Fire of Moscow in September 1812, the FrenchGrande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

had not exactly endeared itself to the local population. The peasant population is said to have become embittered, fanaticized, and even developed an effective guerrilla. In addition, the "wild Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

" lurked about, and both groups of Russians could be a deadly enemy to solitary French soldiers. Some of those unfortunates are said to have been sawn apart.

Hungary

;1848 Revolution The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was a bitter struggle where atrocities were committed against others of different ethnicities and of different religious persuasions. A decidedly partisan pamphlet from 1850, ''Ungarns gutes recht'' (''The well-founded right of Hungary'') from 1850, states that in the struggles aroundBanat

Banat (, ; hu, Bánság; sr, Банат, Banat) is a geographical and historical region that straddles Central and Eastern Europe and which is currently divided among three countries: the eastern part lies in western Romania (the counties of T ...

, some 4,000 Serbians, spurred on by the preaching of the Metropolitan of Karlovci, Josif Rajačić, committed heinous deeds against the Hungarians. Women, children and old men were mutilated, roasted over slow fires, some sawn apart.

Cultural references

Tortures in Hell

;Hindu mythology In Hindu lore,Yama

Yama (Devanagari: यम) or Yamarāja (यमराज), is a deity of death, dharma, the south direction, and the underworld who predominantly features in Hindu and Buddhist religion, belonging to an early stratum of Rigvedic Hindu deities ...

is the god of death. He determines the punishments to those who were wicked in life. Those guilty of robbing a Brahmin

Brahmin (; sa, ब्राह्मण, brāhmaṇa) is a varna as well as a caste within Hindu society. The Brahmins are designated as the priestly class as they serve as priests (purohit, pandit, or pujari) and religious teachers (guru ...

, are to be sawn apart while being in ''Naraka

Naraka ( sa, नरक) is the realm of hell in Indian religions. According to some schools of Hinduism, Sikhism, Jainism and Buddhism, ''Naraka'' is a place of torment. The word ''Neraka'' (modification of ''Naraka'') in Indonesian and Malaysia ...

'' (Hell).

;Chinese mythology

Sawing people asunder is one of the punishments said to occur in Buddhist Hell, and the priests knew how to make a visible spectacle of sufferings in the beyond, by commissioning artists to make paintings the populace were meant to see and reflect upon:

Segare la vecchia

In Italy and Spain, a curious tradition of "segare la vecchia" ("sawing the old woman") was upheld onLaetare Sunday

Laetare Sunday (Church Latin: ; Classical Latin: ; English: , , , , ) is the fourth Sunday in the season of Lent, in the Western Christian liturgical calendar. Traditionally, this Sunday has been a day of celebration, within the austere period ...

(Mid-Lent

Lent ( la, Quadragesima, 'Fortieth') is a solemn religious observance in the liturgical calendar commemorating the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert and enduring temptation by Satan, according to the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke ...

Sunday) in hamlets and towns, well into the 19th century. The custom consisted of the boys running about to find the "oldest woman in the village", and then make a wooden effigy in her likeness. Then, the wooden figure was sawn across the middle. The folklorist Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Karl Grimm (4 January 1785 – 20 September 1863), also known as Ludwig Karl, was a German author, linguist, philologist, jurist, and folklorist. He is known as the discoverer of Grimm's law of linguistics, the co-author of th ...

regards this as an odd spring ritual, in which the "old year"/winter is symbolically defeated. He also notes that a rather similar custom existed in his day among Southern Slavs

South Slavs are Slavic peoples who speak South Slavic languages and inhabit a contiguous region of Southeast Europe comprising the eastern Alps and the Balkan Peninsula. Geographically separated from the West Slavs and East Slavs by Austria, ...

.''Grimm'' (1835p.453

/ref>

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ; Web resources * * * * {{Capital punishment Torture Sawing