Dazai Osamu on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a

, who was later known as Osamu Dazai, was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in

, who was later known as Osamu Dazai, was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary. On March 4, 1923, Tsushima's father Gen'emon died from

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary. On March 4, 1923, Tsushima's father Gen'emon died from  Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer  In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, ''Gyofukuki'' (魚服記, "Transformation", 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include ''Dōke no hana'' (道化の花, "Flowers of Buffoonery", 1935), ''Gyakkō'' (逆行, "Losing Ground", 1935), ''Kyōgen no kami'' (狂言の神, "The God of Farce", 1936), an

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, ''Gyofukuki'' (魚服記, "Transformation", 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include ''Dōke no hana'' (道化の花, "Flowers of Buffoonery", 1935), ''Gyakkō'' (逆行, "Losing Ground", 1935), ''Kyōgen no kami'' (狂言の神, "The God of Farce", 1936), an

Japan entered the

Japan entered the

In July 1947, Dazai's best-known work, ''Shayo'' (''

In July 1947, Dazai's best-known work, ''Shayo'' (''

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the ''

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the ''

''The Setting Sun''

(斜陽 ''Shayō''), translated by

''No Longer Human''

(人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku''), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut,

''Dazai Osamu, Selected Stories and Sketches''

translated by James O’Brien. Ithaca, New York, China-Japan Program,

Return to Tsugaru: Travels of a Purple Tramp

' (津軽), translated by James Westerhoven. New York,

Crackling Mountain and Other Stories

', translated by James O’Brien. Rutland, Vermont,

Blue Bamboo: Tales of Fantasy and Romance

', translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo and New York,

Kurodahan Press

2011. * ''Blue Bamboo: Tales by Dazai Osamu'' (竹青 ''Chikusei''), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka

Kurodahan Press

2012. *

A Shameful Life: (Ningen Shikkaku)

' (人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku''), translated by Mark Gibeau. Berkeley,

"Wish Fulfilled" (満願)

translated by Reiko Seri and Doc Kane. Kobe, Japan, 2019.

e-texts of Osamu's works

at

Osamu Dazai's grave

at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dazai, Osamu 1909 births 1948 suicides 20th-century Japanese novelists Japanese male short story writers People of the Empire of Japan Writers from Aomori Prefecture University of Tokyo alumni Suicides by drowning in Japan 20th-century Japanese short story writers 20th-century male writers Joint suicides

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese author

An author is the writer of a book, article, play, mostly written work. A broader definition of the word "author" states:

"''An author is "the person who originated or gave existence to anything" and whose authorship determines responsibility f ...

. A number of his most popular works, such as ''The Setting Sun

is a Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai first published in 1947. The story centers on an aristocratic family in decline and crisis during the early years after World War II.

Plot summary

Twenty-nine year old Kazuko, her brother Naoji, and their wi ...

'' (''Shayō'') and ''No Longer Human

is a 1948 Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai. It is considered Dazai's masterpiece and ranks as the second-best selling novel ever in Japan, behind Natsume Sōseki's ''Kokoro''. The literal translation of the title, discussed by Donald Keene in his ...

'' (''Ningen Shikkaku''), are considered modern-day classics.

His influences include Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

, art name , was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He committed suicide at the age of ...

, Murasaki Shikibu

was a Japanese novelist, poet and lady-in-waiting at the Imperial court in the Heian period. She is best known as the author of '' The Tale of Genji,'' widely considered to be one of the world's first novels, written in Japanese between abou ...

and Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

. While Dazai continues to be widely celebrated in Japan, he remains relatively unknown elsewhere, with only a handful of his works available in English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

. His last book, ''No Longer Human'', is his most popular work outside of Japan.

Early life

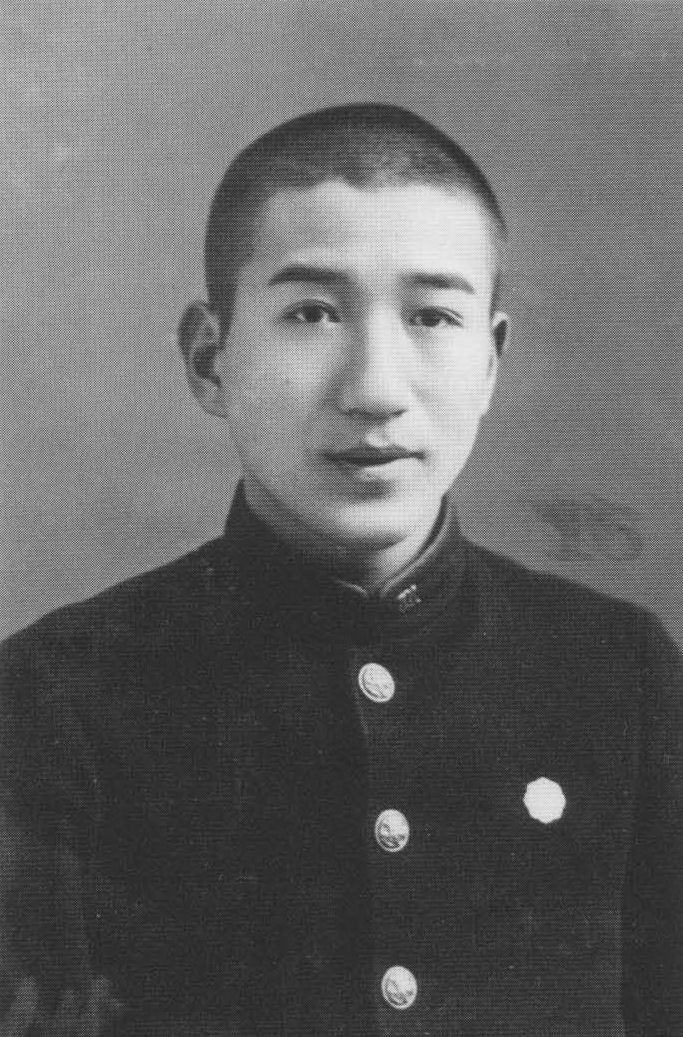

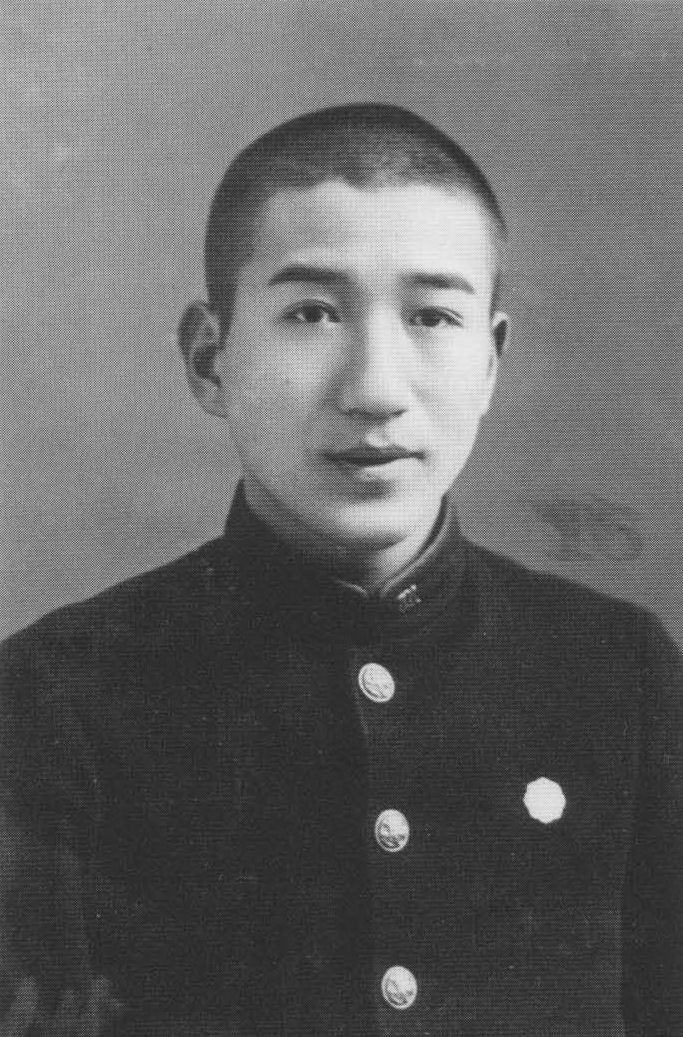

, who was later known as Osamu Dazai, was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in

, who was later known as Osamu Dazai, was born on June 19, 1909, the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner in Kanagi, a remote corner of Japan at the northern tip of Tōhoku in Aomori Prefecture

is a prefecture of Japan in the Tōhoku region. The prefecture's capital, largest city, and namesake is the city of Aomori. Aomori is the northernmost prefecture on Japan's main island, Honshu, and is bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the east, ...

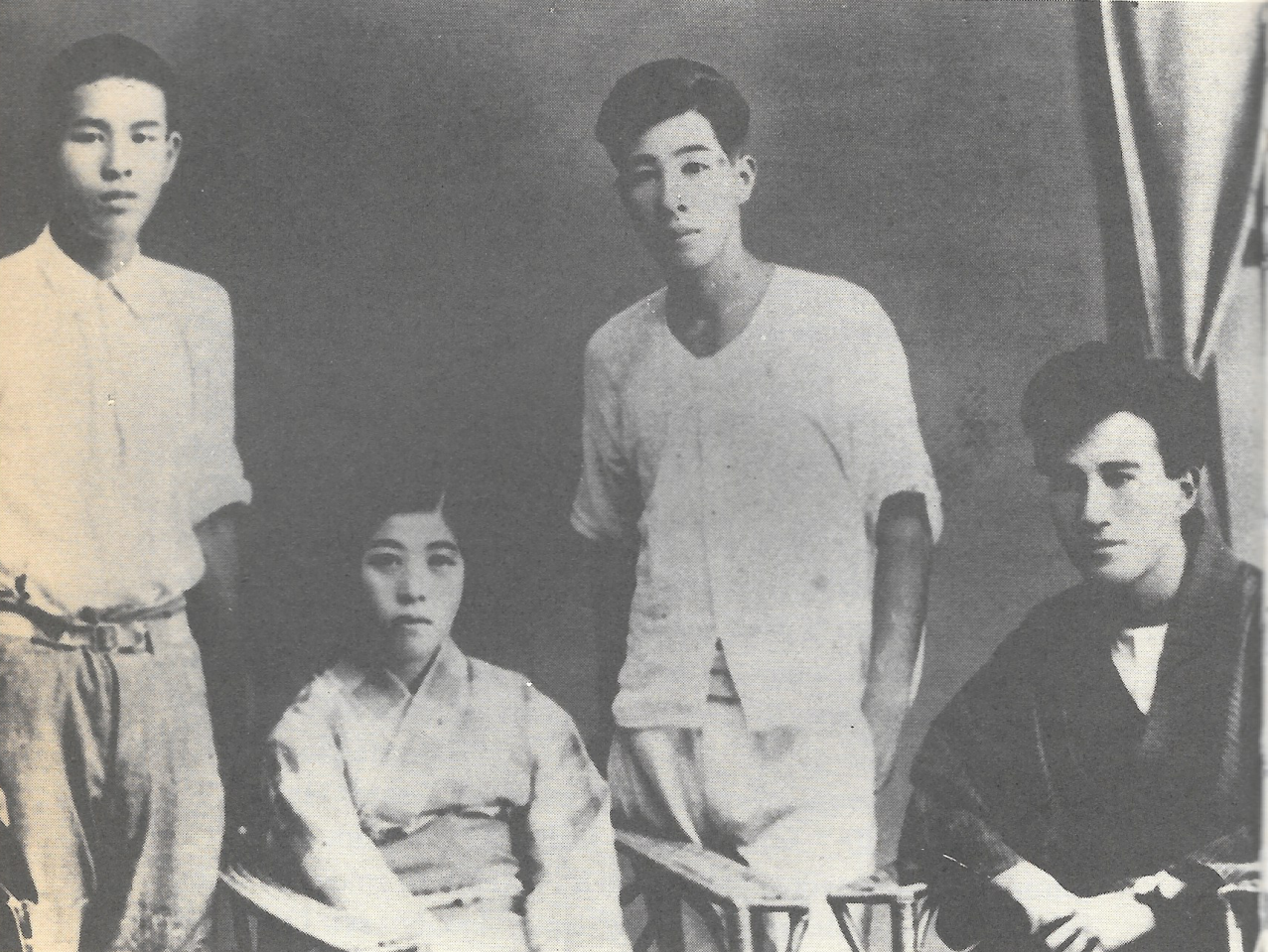

. At the time of his birth, the huge, newly-completed Tsushima mansion where he would spend his early years was home to some thirty family members. The Tsushima family was of obscure peasant origins, with Dazai's great-grandfather building up the family's wealth as a moneylender, and his son increasing it further. They quickly rose in power and, after some time, became highly respected across the region.

Dazai's father, Gen'emon (a younger son of the Matsuki family, which due to "its exceedingly 'feudal' tradition" had no use for sons other than the eldest son and heir) was adopted into the Tsushima family to marry the eldest daughter, Tane; he became involved in politics due to his position as one of the four wealthiest landowners in the prefecture, and was offered membership into the House of Peers. This made Dazai's father absent during much of his early childhood, and with his mother, Tane, being ill, Tsushima was brought up mostly by the family's servants and his aunt Kiye.

Education and literary beginnings

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary. On March 4, 1923, Tsushima's father Gen'emon died from

In 1916, Tsushima began his education at Kanagi Elementary. On March 4, 1923, Tsushima's father Gen'emon died from lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissue (biology), tissues of the lung. Lung carcinomas derive from tran ...

, and then a month later in April Tsushima attended Aomori High School

is a high school in the city of Aomori, Aomori Prefecture, Japan.

Originally a junior high school named , the school was established on September 11, 1900.

Aomori Prefectural First Junior High School in Hirosaki and Aomori Prefectural Second ...

, followed by entering Hirosaki University

is a Japanese national university in Hirosaki, Aomori Prefecture, Japan. Established in 1949, it comprises five faculties: Faculty of the Humanities, Faculty of Education History, Hirosaki University Medical School History, Faculty of Science a ...

's literature department in 1927. He developed an interest in Edo culture and began studying gidayū, a form of chanted narration used in the puppet theaters

A puppet is an object, often resembling a human, animal or mythical figure, that is animated or manipulated by a person called a puppeteer. The puppeteer uses movements of their hands, arms, or control devices such as rods or strings to move ...

. Around 1928, Tsushima edited a series of student publications and contributed some of his own works. He also published a magazine called ''Saibō bungei'' (''Cell Literature'') with his friends, and subsequently became a staff member of the college's newspaper.

Tsushima's success in writing was brought to a halt when his idol, the writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

, art name , was a Japanese writer active in the Taishō period in Japan. He is regarded as the "father of the Japanese short story", and Japan's premier literary award, the Akutagawa Prize, is named after him. He committed suicide at the age of ...

, committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in 1927 at 35 years old. Tsushima started to neglect his studies, and spent the majority of his allowance on clothes, alcohol, and prostitute

Prostitution is the business or practice of engaging in sexual activity in exchange for payment. The definition of "sexual activity" varies, and is often defined as an activity requiring physical contact (e.g., sexual intercourse, non-penet ...

s. He also dabbled with Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, which at the time was heavily suppressed by the government. On the night of December 10, 1929, Tsushima committed his first suicide attempt, but survived and was able to graduate the following year. In 1930, Tsushima enrolled in the French Literature

French literature () generally speaking, is literature written in the French language, particularly by citizens of France; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of France other than Fr ...

Department of Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

and promptly stopped studying again. In October, he ran away with a geisha

{{Culture of Japan, Traditions, Geisha

{{nihongo, Geisha, 芸者 ({{IPAc-en, ˈ, ɡ, eɪ, ʃ, ə; {{IPA-ja, ɡeːɕa, lang), also known as {{nihongo, , 芸子, geiko (in Kyoto and Kanazawa) or {{nihongo, , 芸妓, geigi, are a class of female ...

named and was formally disowned

Disownment occurs when a parent renounces or no longer accepts a child as a family member, usually due to reprehensible actions leading to serious emotional consequences. Different from giving a child up for adoption, it is a social and interpers ...

by his family.

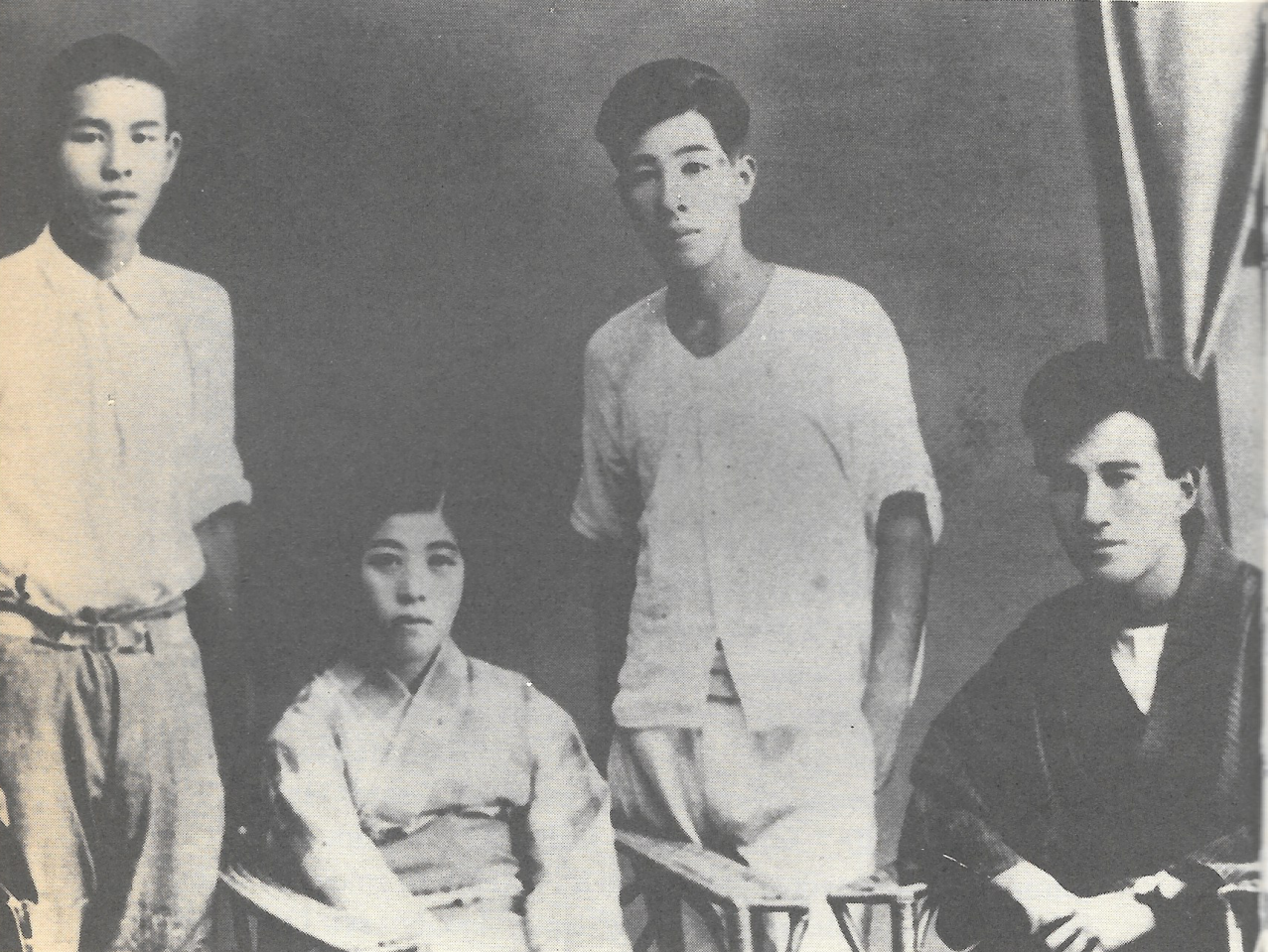

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in

Nine days after being expelled from Tokyo Imperial University, Tsushima attempted suicide by drowning off a beach in Kamakura

is a city in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

Kamakura has an estimated population of 172,929 (1 September 2020) and a population density of 4,359 persons per km² over the total area of . Kamakura was designated as a city on 3 November 1939.

Kamak ...

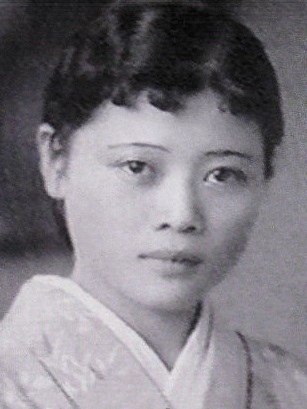

with another woman, 19-year-old bar hostess . Tanabe died, but Tsushima lived, rescued by a fishing boat and was charged as an accomplice in Tanabe's death. Shocked by the events, Tsushima's family intervened to drop a police investigation. His allowance was reinstated, and he was released of any charges. In December, Tsushima recovered at Ikarigaseki and married Hatsuyo there.

Soon after, Tsushima was arrested for his involvement with the banned Japanese Communist Party

The is a left-wing to far-left political party in Japan. With approximately 270,000 members belonging to 18,000 branches, it is one of the largest non-governing communist parties in the world.

The party advocates the establishment of a democr ...

and, upon learning this, his elder brother Bunji promptly cut off his allowance again. Tsushima went into hiding, but Bunji, despite their estrangement, managed to get word to him that charges would be dropped and the allowance reinstated yet again if Tsushima solemnly promised to graduate and swear off any involvement with the party. Tsushima accepted.

Leftist movement

In1929

This year marked the end of a period known in American history as the Roaring Twenties after the Wall Street Crash of 1929 ushered in a worldwide Great Depression. In the Americas, an agreement was brokered to end the Cristero War, a Catholic ...

, when its principal's misappropriation of public funds was discovered at Hirosaki High School, the students, under the leadership of Ueda Shigehiko (Ishigami Genichiro), leader of the Social Science Study Group, staged a five-day allied strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

, which resulted in the principal's resignation and no disciplinary action against the students. Tsushima hardly participated in the strike

Strike may refer to:

People

* Strike (surname)

Physical confrontation or removal

*Strike (attack), attack with an inanimate object or a part of the human body intended to cause harm

*Airstrike, military strike by air forces on either a suspected ...

, but in imitation of the proletarian literature

Proletarian literature refers here to the literature created by left-wing writers mainly for the class-conscious proletariat. Though the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' states that because it "is essentially an intended device of revolution", it is ...

in vogue at the time, he summarized the incident in a novel called ''Student Group'' and read it to Ueda. The Tsushima family was wary of Dazai's leftist activities. On January 16 of the following year, the Special High Police arrested Ueda and nine other students of the Hiroko Institute of Social Studies, who were working as terminal activists for Seigen Tanaka's armed Communist Party.

In college, Dazai met activist Eizo Kudo, and made a monthly financial contribution of ¥10 to the Communist Party. The reason why he was expelled from his family after his marriage with Hatsuyo Oyama was to prevent the accumulation of illegal activities on Bunji, who was a politician. After his marriage, Dazai was ordered to hide his sympathies and moved repeatedly. In July 1932

Events January

* January 4 – The British authorities in India arrest and intern Mahatma Gandhi and Vallabhbhai Patel.

* January 9 – Sakuradamon Incident (1932), Sakuradamon Incident: Korean nationalist Lee Bong-chang fails in his effort ...

, Bunji tracked him down, and had him turn himself in at the Aomori Police Station. In December, Dazai signed and sealed a pledge at the Aomori Prosecutor's Office to completely withdraw from leftist activities.

Early literary career

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer

Tsushima kept his promise and settled down a bit. He managed to obtain the assistance of established writer Masuji Ibuse

was a Japanese author. His most notable work is the novel '' Black Rain''.

Early life and education

Ibuse was born in 1898 to a landowning family in the village of , which is now part of Fukuyama, Hiroshima.

Ibuse failed his entrance exam to ...

, whose connections helped him get his works published and establish his reputation. The next few years were productive for Tsushima. He wrote at a feverish pace and used the pen name "Osamu Dazai" for the first time in a short story

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest ...

called "Ressha" ("列車", "Train") in 1933: His first experiment with the first-person autobiographical style that later became his trademark.

However, in 1935 it started to become clear to Dazai that he would not graduate. He failed to obtain a job at a Tokyo newspaper as well. He finished ''The Final Years

''The Final Years'' (Japanese: 晩年, Hepburn: ''Bannen'') is a Japanese short story collection written by Osamu Dazai and was published in 1936. It was Dazai's first published book, composed of fifteen previously published short stories, and w ...

'' (''Bannen''), which was intended to be his farewell to the world, and tried to hang himself March 19, 1935, failing yet again. Less than three weeks later, Tsushima developed acute appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a rup ...

and was hospitalized. In the hospital, he became addicted to Pavinal, a morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a analgesic, pain medication, and is also commonly used recreational drug, recreationally, or to make ...

-based painkiller

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic (American English), analgaesic (British English), pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used to achieve relief from pain (that is, analgesia or pain management). It i ...

. After fighting the addiction for a year, in October 1936 he was taken to a mental institution

Psychiatric hospitals, also known as mental health hospitals, behavioral health hospitals, are hospitals or wards specializing in the treatment of severe mental disorders, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, dissociative ...

, locked in a room and forced to quit cold turkey

"Cold turkey" refers to the abrupt cessation of a substance dependence and the resulting unpleasant experience, as opposed to gradually easing the process through reduction over time or by using replacement medication.

Sudden withdrawal from dru ...

.

The treatment lasted over a month. During this time Tsushima's wife Hatsuyo committed adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

with his best friend Zenshirō Kodate. This eventually came to light, and Tsushima attempted to commit double suicide with his wife. They both took sleeping pills, but neither died. Soon after, Dazai divorced Hatsuyo. He quickly remarried, this time to a middle school teacher named Michiko Ishihara ( 石原美知子). Their first daughter, Sonoko ( 園子), was born in June 1941.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, ''Gyofukuki'' (魚服記, "Transformation", 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include ''Dōke no hana'' (道化の花, "Flowers of Buffoonery", 1935), ''Gyakkō'' (逆行, "Losing Ground", 1935), ''Kyōgen no kami'' (狂言の神, "The God of Farce", 1936), an

In the 1930s and 1940s, Dazai wrote a number of subtle novels and short stories that are autobiographical in nature. His first story, ''Gyofukuki'' (魚服記, "Transformation", 1933), is a grim fantasy involving suicide. Other stories written during this period include ''Dōke no hana'' (道化の花, "Flowers of Buffoonery", 1935), ''Gyakkō'' (逆行, "Losing Ground", 1935), ''Kyōgen no kami'' (狂言の神, "The God of Farce", 1936), an epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

called ''Kyokō no Haru'' (虚構の春, ''False Spring'', 1936) and those published in his 1936 collection ''Bannen'' (''Declining Years'' or ''The Final Years''), which describe his sense of personal isolation and his debauchery

Debauchery may refer to:

* Corruption

*Libertinism

*Lust

* Binge drinking

* Currency debasement

*Debauchery (band), a German death metal band

See also

*''Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery'', a 1684 closet drama.

*LGBT rights in Kuwait

...

.

Wartime years

Japan entered the

Japan entered the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

in December, but Tsushima was excused from the draft because of his chronic chest problems, as he was diagnosed with tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

. The censors became more reluctant to accept Dazai's offbeat work, but he managed to publish quite a bit regardless, remaining one of very few authors who managed to get this kind of material accepted in this period. A number of the stories which Dazai published during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

were retellings of stories by Ihara Saikaku

was a Japanese poet and creator of the " floating world" genre of Japanese prose (''ukiyo-zōshi'').

Born as Hirayama Tōgo (平山藤五), the son of a wealthy merchant in Osaka, he first studied haikai poetry under Matsunaga Teitoku and later ...

(1642–1693). His wartime works included ''Udaijin Sanetomo'' (右大臣実朝, "Minister of the Right Sanetomo", 1943), ''Tsugaru'' (1944), ''Pandora no hako'' (パンドラの匣, ''Pandora's Box'', 1945–46), and ''Otogizōshi'' (お伽草紙, ''Fairy Tales'', 1945) in which he retold a number of old Japanese fairy tales

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic, enchantments, and mythical or fanciful beings. In most cult ...

with "vividness and wit."

Dazai's house was burned down twice in the American bombing of Tokyo, but his family escaped unscathed, with a son, Masaki ( 正樹), born in 1944. His third child, daughter Satoko ( 里子), who later became a famous writer under the pseudonym Yūko Tsushima

Satoko Tsushima (30 March 1947 – 18 February 2016), known by her pen name Yūko Tsushima (津島 佑子 ''Tsushima Yūko''), was a Japanese fiction writer, essayist and critic. Tsushima won many of Japan's top literary prizes in her career, i ...

(津島佑子), was born in May 1947.

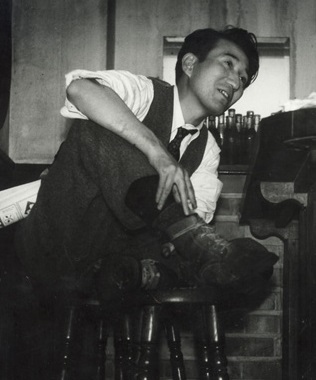

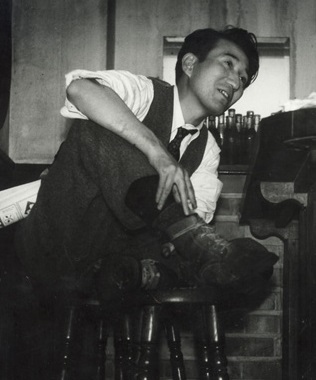

Postwar career

In the immediate postwar period, Dazai reached the height of his popularity. He depicted a dissolute life in postwar Tokyo in ''Viyon no Tsuma'' (ヴィヨンの妻, "Villon's Wife", 1947), depicting the wife of a poet who had abandoned her and her continuing will to live through hardships. In 1946, Osamu Dazai released a controversial literary piece titled ''Kuno no Nenkan (Almanac of Pain),'' a political memoir of Dazai himself. It describes the immediate aftermath of losing the second World War, and encapsulates how Japanese people felt following the country's defeat. Dazai reaffirms his loyalty to the Japanese Emperor of the time,Emperor Hirohito

Emperor , commonly known in English-speaking countries by his personal name , was the 124th emperor of Japan, ruling from 25 December 1926 until his death in 1989. Hirohito and his wife, Empress Kōjun, had two sons and five daughters; he was ...

and his son Akihito

is a member of the Imperial House of Japan who reigned as the 125th emperor of Japan from 7 January 1989 until his abdication on 30 April 2019. He presided over the Heisei era, ''Heisei'' being an expression of achieving peace worldwide.

Bo ...

. Dazai was a known communist throughout his career, and also expresses his beliefs through this ''Almanac of Pain''.

Alongside this Dazai also wrote ''Jugonenkan'' (''For Fifteen Years''), another autobiographical piece. This, alongside ''Almanac of Pain'', may serve as a prelude to a consideration of Dazai's postwar fiction. In July 1947, Dazai's best-known work, ''Shayo'' (''

In July 1947, Dazai's best-known work, ''Shayo'' (''The Setting Sun

is a Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai first published in 1947. The story centers on an aristocratic family in decline and crisis during the early years after World War II.

Plot summary

Twenty-nine year old Kazuko, her brother Naoji, and their wi ...

'', translated 1956) depicting the decline of the Japanese nobility

The was the hereditary peerage of the Empire of Japan, which existed between 1869 and 1947. They succeeded the feudal lords () and court nobles (), but were abolished with the 1947 constitution.

Kazoku ( 華族) should not be confused with ' ...

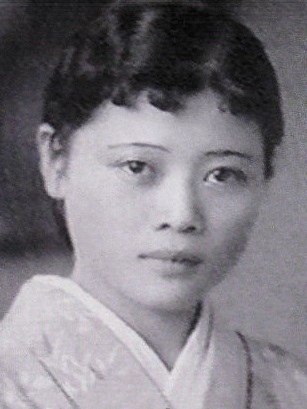

after the war, was published, propelling the already popular writer into celebrityhood. This work was based on the diary of Shizuko Ōta ( 太田静子), an admirer of Dazai's works who first met him in 1941. She bore him a daughter, Haruko, ( 治子) in 1947.

A heavy drinker, Dazai became an alcoholic

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomin ...

and his health deteriorated rapidly. At this time he met Tomie Yamazaki ( 山崎富栄), a beautician and war widow who had lost her husband after just ten days of marriage. Dazai effectively abandoned his wife and children and moved in with Tomie.

Dazai began writing his novel ''No Longer Human

is a 1948 Japanese novel by Osamu Dazai. It is considered Dazai's masterpiece and ranks as the second-best selling novel ever in Japan, behind Natsume Sōseki's ''Kokoro''. The literal translation of the title, discussed by Donald Keene in his ...

'' (人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku'', 1948) at the hot-spring resort Atami

is a city located in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 36,865 in 21,593 households and a population density of 600 persons per km2. The total area of the city is .

Geography

Atami is located in the far ea ...

. He moved to Ōmiya Ōmiya 大宮 is a Japanese word originally used for the imperial palace or shrines, now a common name, and may refer to:

People

*Ōmiya (surname), a Japanese surname

*Ōmiya, or is a female character in ''The Tale of Genji'', an 11th-century nove ...

with Tomie and stayed there until mid-May, finishing his novel. A quasi-autobiography, it depicts a young, self-destructive man seeing himself as disqualified from the human race. The book is considered one of the classics of Japanese literature

Japanese literature throughout most of its history has been influenced by cultural contact with neighboring Asian literatures, most notably China and its literature. Early texts were often written in pure Classical Chinese or , a Chinese-Japanes ...

and has been translated into several foreign languages.

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the ''

In the spring of 1948, Dazai worked on a novelette scheduled to be serialized in the ''Asahi Shimbun

is one of the four largest newspapers in Japan. Founded in 1879, it is also one of the oldest newspapers in Japan and Asia, and is considered a newspaper of record for Japan. Its circulation, which was 4.57 million for its morning edition and ...

'' newspaper, titled ''Guddo bai'' (the Japanese pronunciation of the English word "Goodbye") but it was never finished.

Death

On June 13, 1948, Dazai and Tomie drowned themselves in the rain-swollen Tamagawa Canal, near his house. Their bodies were not discovered until six days later, on June 19, which would have been his 39th birthday. His grave is at the temple of Zenrin-ji, inMitaka, Tokyo

260px, Inokashira Park in Mitaka

is a city in the western portion of Tokyo Metropolis, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 190,403, and a population density of 12,000 persons per km². The total area of the city was .

Geography

Mit ...

.

At the time, there was a lot of speculation about the incident, with theories of forced suicide

Forced suicide is a method of execution where the victim is coerced into committing suicide to avoid facing an alternative option they perceive as much worse, such as suffering torture, public humiliation, or having friends or family members impr ...

by Tomie. Keikichi Nakahata, a kimono merchant who frequented the young Tsushima family, was shown the scene of the water ingress by a detective from the Mitaka police station. He also speculates that "Dazai was asked to die, and he simply agreed, but just before his death, he suddenly felt an obsession with life".

Major works

;''Omoide'' :"Omoide" is an autobiography where Tsushima created a character named Osamu to use instead of himself to enact his own memories. Furthermore, Tsushima also conveys his perspective and analysis of these situations. ;''Flowers of Buffoonery'' :"Flowers of Buffoonery" relates the story of Oba Yozo and his time recovering in the hospital from an attempted suicide. Although his friends attempt to cheer him up, their words are fake, and Oba sits in the hospital simply reflecting on his life. ;''One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji'' :"One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji" shares Tsushima's experience staying at Misaka. He meets with a man named Ibuse Masuji, a previous mentor, who has arranged an o-miai for Dazai. Dazai meets the woman, Ishihara Michiko, who he later decides to marry. ;''The Setting Sun'' :''The Setting Sun'' focuses on a small, formerly rich, family: a widowed mother, a divorced daughter, and a drug-addicted son who has just returned from the army and the war in the South Pacific. After WWII the family has to vacate their Tokyo home and move to the countryside, inIzu, Shizuoka

is a city located in central Izu Peninsula in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 30,678 in 13,390 households, and a population density of 84 persons per km2. The total area of the city was .

Geography

Izu ...

, as the daughter's uncle can no longer support them financially

;''No Longer Human''

:''No Longer Human'' focuses on the main character, Oba Yozo. Oba explains his life from a point in his childhood to somewhere in adulthood. Unable to properly understand how to interact and understand people he resorts to tomfoolery to make friends and hide his misinterpretations of social cues. His façade doesn't fool everyone and doesn't solve every problem. Due to the influence of a classmate named Horiki, he falls into a world of drinking and smoking. He relies on Horiki during his time in college to assist with social situations. With his life spiraling downwards after failing in college, Oba continues his story and conveys his feelings about the people close to him and society in general.

;''Good-Bye''

:An editor tries to avoid women with whom he had past sexual relations. Using the help of a female friend he does his best to avoid their advances and hide the unladylike qualities of his friend.

Selected bibliography of English translations

''The Setting Sun''

(斜陽 ''Shayō''), translated by

Donald Keene

Donald Lawrence Keene (June 18, 1922 – February 24, 2019) was an American-born Japanese scholar, historian, teacher, writer and translator of Japanese literature. Keene was University Professor emeritus and Shincho Professor Emeritus of Japan ...

. Norfolk, Connecticut, James Laughlin

James Laughlin (October 30, 1914 – November 12, 1997) was an American poet and literary book publisher who founded New Directions Publishing.

Early life

He was born in Pittsburgh, the son of Henry Hughart and Marjory Rea Laughlin. Laughlin ...

, 1956. (Japanese publication: 1947).

''No Longer Human''

(人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku''), translated by Donald Keene. Norfolk, Connecticut,

New Directions Publishers

New Directions Publishing Corp. is an independent book publishing company that was founded in 1936 by James Laughlin and incorporated in 1964. Its offices are located at 80 Eighth Avenue in New York City.

History

New Directions was born in 19 ...

, 1958.

''Dazai Osamu, Selected Stories and Sketches''

translated by James O’Brien. Ithaca, New York, China-Japan Program,

Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

, 1983?

* Return to Tsugaru: Travels of a Purple Tramp

' (津軽), translated by James Westerhoven. New York,

Kodansha

is a Japanese privately-held publishing company headquartered in Bunkyō, Tokyo. Kodansha is the largest Japanese publishing company, and it produces the manga magazines ''Nakayoshi'', ''Afternoon'', ''Evening'', ''Weekly Shōnen Magazine'' an ...

International Ltd., 1985.

* ''Run, Melos! and Other Stories''. Trans. Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988. Tokyo: Kodansha English Library, 1988.

* Crackling Mountain and Other Stories

', translated by James O’Brien. Rutland, Vermont,

Charles E. Tuttle Company

Tuttle Publishing, originally the Charles E. Tuttle Company, is a book publishing company that includes Tuttle, Periplus Editions, and Journey Editions.

, 1989.

* ''Self Portraits: Tales from the Life of Japan's Great Decadent Romantic'', translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo, New York, Kodansha International, Ltd., 1991.

* Blue Bamboo: Tales of Fantasy and Romance

', translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Tokyo and New York,

Kodansha

is a Japanese privately-held publishing company headquartered in Bunkyō, Tokyo. Kodansha is the largest Japanese publishing company, and it produces the manga magazines ''Nakayoshi'', ''Afternoon'', ''Evening'', ''Weekly Shōnen Magazine'' an ...

International, 1993.

* ''Schoolgirl'' (女生徒 ''Joseito''), translated by Allison Markin Powell. New York: One Peace Books

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1 ...

, 2011.

* '' Otogizōshi: The Fairy Tale Book of Dazai Osamu'' (お伽草紙 ''Otogizōshi''), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. FukuokaKurodahan Press

2011. * ''Blue Bamboo: Tales by Dazai Osamu'' (竹青 ''Chikusei''), translated by Ralph F. McCarthy. Fukuoka

Kurodahan Press

2012. *

A Shameful Life: (Ningen Shikkaku)

' (人間失格 ''Ningen Shikkaku''), translated by Mark Gibeau. Berkeley,

Stone Bridge Press

Stone Bridge Press, Inc. is a publishing company distributed by Consortium Book Sales & Distribution and founded in 1989. Authors published include Donald Richie and Frederik L. Schodt. Stone Bridge publishes books related to Japan, having pu ...

, 2018.

"Wish Fulfilled" (満願)

translated by Reiko Seri and Doc Kane. Kobe, Japan, 2019.

In popular culture

Dazai's literary work ''No Longer Human'' has received quite a few adaptations: agraphic novel

A graphic novel is a long-form, fictional work of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comic scholars and industry ...

written by the horror manga artist Junji Ito

is a Japanese horror manga artist. Some of his most notable works include ''Tomie'', a series chronicling an immortal girl who drives her stricken admirers to madness; ''Uzumaki'', a three-volume series about a town obsessed with spirals; and ...

, a film directed by Genjiro Arato

was a Japanese film producer, actor and director.

Career

In 1980, Arato produced '' Zigeunerweisen'' for director Seijun Suzuki. He was unable to secure exhibitors for the film and famously exhibited it himself in a specially-built, inflatabl ...

, the first four episodes of the anime

is Traditional animation, hand-drawn and computer animation, computer-generated animation originating from Japan. Outside of Japan and in English, ''anime'' refers specifically to animation produced in Japan. However, in Japan and in Japane ...

series ''Aoi Bungaku

is a twelve episode Japanese anime series featuring adaptations inspired by six short stories from Japanese literature. The six stories are adapted from classic Japanese tales. Happinet, Hakuhodo DY Media Partners, McRAY, MTI, Threelight Hold ...

'', and a variety of mangas one of which was serialized in Shinchosha

is a publisher founded in 1896 in Japan and headquartered in Yaraichō, Shinjuku, Tokyo. Shinchosha is one of the sponsors of the Japan Fantasy Novel Award.

Books

* Haruki Murakami: ''Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World'' (1985), ...

's ''Comic Bunch

is a Japanese manga anthology marketed to a ''seinen'' audience that was edited by Coamix and published weekly by Shinchosha from 2001 throughout 2010 and became monthly since 2011. The collected editions of their titles are published under th ...

'' magazine. It is also the name of an ability in the anime '' Bungo Stray Dogs'' and ''Bungo and Alchemist

, also known as , is a free-to-play collectible card browser video game launched in Japan on November 1, 2016 with a mobile port of the game releasing on June 14, 2017. The game is developed by EXNOA and published by DMM.com.

Gameplay

In the ...

'', used by a character named after Dazai himself.

The book is also the central work in one of the volumes of the Japanese light novel series ''Book Girl

is a collection of Japanese light novels by Mizuki Nomura, with illustrations by Miho Takeoka. The series contains 16 volumes: eight cover the original series, four are short story collections, and four are of a side story. The novels w ...

'', ''Book Girl and the Suicidal Mime'', although other works of his are also mentioned. Dazai's works are also discussed in the ''Book Girl'' manga and anime series. Dazai is often quoted by the male protagonist, Kotaro Azumi, in the anime series ''Tsuki ga Kirei

is a Japanese romance anime television series produced by Feel. It originally aired from April 6 to June 29, 2017. Crunchyroll has licensed the series in North America.

As a coming-of-age contemporary romance, the story follows the lives of tw ...

'', as well as by Ken Kaneki in ''Tokyo Ghoul

is a Japanese dark fantasy manga series written and illustrated by Sui Ishida. It was serialized in Shueisha's ''seinen'' manga magazine ''Weekly Young Jump'' between September 2011 and September 2014, and was collected in four ...

''.

See also

*Dazai Osamu Prize

The Dazai Osamu Prize (太宰治賞) is a Japanese literary prize named for novelist Dazai Osamu (1909–1948).

The prize was established in 1965 by the Chikuma Shobō publishing company, discontinued in 1978, and resumed again in 1999 with co-spo ...

*List of Japanese writers

This is an alphabetical list of writers who are Japanese, or are famous for having written in the Japanese language.

Writers are listed by the native order of Japanese names, family name followed by given name to ensure consistency although some ...

*Osamu Dazai Memorial Museum

The , also commonly referred to as , is a writer's home museum located in the Kanagi area of Goshogawara in Aomori Prefecture, Japan. It is dedicated to the late author Osamu Dazai, who spent some of his early childhood in Kanagi, and houses ant ...

References

Sources

* O'Brien, James A., ed. ''Akutagawa and Dazai: Instances of Literary Adaptation''. Cornell University Press, 1983. * Ueda, Makoto. ''Modern Japanese Writers and the Nature of Literature''. Stanford University Press, 1976. * "Nation and Region in the Work of Dazai Osamu," inRoy Starrs

Roy Starrs (born 1946) is a British-Canadian scholar of Japanese literature and culture who teaches at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He has written critical studies of the major Japanese writers Yasunari Kawabata, Naoya Shiga, Osamu Dazai ...

External links

e-texts of Osamu's works

at

Aozora bunko

Aozora Bunko (, literally the "Blue Sky Library", also known as the "Open Air Library") is a Japanese digital library. This online collection encompasses several thousands of works of Japanese-language fiction and non-fiction. These include out-o ...

*Osamu Dazai's grave

at JLPP (Japanese Literature Publishing Project) * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Dazai, Osamu 1909 births 1948 suicides 20th-century Japanese novelists Japanese male short story writers People of the Empire of Japan Writers from Aomori Prefecture University of Tokyo alumni Suicides by drowning in Japan 20th-century Japanese short story writers 20th-century male writers Joint suicides