Davis Gelatine on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir George Francis Davis (1883 – 1947) was a New Zealand born industrialist. He is notable mainly for his association with Davis Gelatine,

Cockatoo Island Dockyard

The Cockatoo Island Dockyard was a major dockyard in Sydney, Australia, based on Cockatoo Island. The dockyard was established in 1857 to maintain Royal Navy warships. It later built and repaired military and battle ships, and played a key role ...

, and the Glen Davis Shale Oil Works

The Glen Davis Shale Oil Works was a shale oil extraction plant, in the Capertee Valley, at Glen Davis, New South Wales, Australia, which operated from 1940 until 1952. It was the last oil-shale operation in Australia, until the Stuart Oil Shal ...

, in Australia. Glen Davis, New South Wales

Glen Davis is a village in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales, Australia. The village is located in the local government area of the City of Lithgow. It is located 250 km north-west of Sydney and approximately 80 kilometres north of ...

is named after him.

Early life and family background

He was born atNew Lynn

New Lynn is a residential suburb in West Auckland, New Zealand, located 10 kilometres to the southwest of the Auckland city centre. The suburb is located along the Whau River, one of the narrowest points of the North Island, and was the locat ...

, a suburb of Auckland, on 22 November 1883. His parents were Charles George Davis and Lillian Edwedinah, née Ball, and he was their third and youngest son. Davis attended King's College, Auckland

King's College (Latin: ''Collegium Regis''; mi, Kīngi Kāreti), often informally referred to simply as King's, is an independent secondary boarding and day school in New Zealand. It educates over 1000 pupils, aged 13 to 18 years. King's was o ...

. He left school at fifteen, and went to sea for four years in the sailing ships of John Emery and Co., Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. He was later to say that he wanted to join the navy, but was not accepted due to his poor hearing.

Both the Davis and Ball families were involved in glue manufacture in England. His parents had emigrated from England in 1879, intending to farm in New Zealand. Instead Charles Davis set up a small glue factory at New Lynn in 1881, moving to a new larger factory at Onehunga

Onehunga is a suburb of Auckland in New Zealand and the location of the Port of Onehunga, the city's small port on the Manukau Harbour. It is south of the city centre, close to the volcanic cone of Maungakiekie / One Tree Hill.

Onehunga is a ...

in 1888. The eldest son Charles Christopher (Chris) Davis was working in factory from 1892. By 1899 Chris was the manager of the company that his father formed in that year, New Zealand Glue Co. Ltd, in which his father held a one third share.

Business in New Zealand

It was not until 1901 that Davis joined the family business. In 1903, his father bought out the other shareholders, and divided those shares equally between Davis and his elder brother Chris. In 1909, the company bought a rival manufacturer based atWoolston

Woolston may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Woolston, Cheshire, a village and civil parish in Warrington

* Woolston, Devon, on the list of United Kingdom locations: Woof-Wy near Kingsbridge, Devon

* Woolston, Southampton, a city suburb in Ham ...

, a suburb of Christchurch

Christchurch ( ; mi, Ōtautahi) is the largest city in the South Island of New Zealand and the seat of the Canterbury Region. Christchurch lies on the South Island's east coast, just north of Banks Peninsula on Pegasus Bay. The Avon Rive ...

, and George became the manager of the Woolston factory.

When their father died in April 1913, the two brothers decided to expand into the production of gelatin. George went to England to learn the craft from some of his mother’s family. In 1913, plant for the manufacture of gelatin was added to the Woolston factory. It was soon supplying not only New Zealand but also Australia and Canada. In 1915, the middle brother, Maurice, who had been working as a marine engineer, joined Davis at the Woolston factory.

The mundane industry of gelatin and glue production, from animal skins, sinews, and bones, waste products of the meat industry, would make the Davis family's fortune.

Expansion to Australia

After a share issue in 1916, a decision was made to expand to Australia. George who had set up gelatin manufacturing in New Zealand was chosen to set up a new factory in Australia. He arrived in Sydney at the end of October 1917, and immediately bought 8 ha of land atBotany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, a suburb of Sydney, Foundations of the new factory were laid, in December 1917, and it produced its first gelatin in early January 1919. Botany was already the site of tanneries and other industries that produced by products of meat production, to which was added the gelatin made by the new factory.

Following the same pattern as in New Zealand, the Davis family bought out competitors in Australia and expanded the Botany factory. Davis’s maternal cousin Jack Ball emigrated to Australia, in 1924, and became manager of the Botany factory and a director of the Australian company.

Davis Gelatine

Between 1921 and 1926, the family interests were restructured so that the Australian company, Davis Gelatine (Australia) Pty Ltd, became the holding company, with subsidiary companies in New Zealand, South Africa and Canada, all under the name Davis Gelatine. George Davis was Managing Director of the company. The organisation sought additional capital from the public in late 1921, floating Davis Gelatine (Australia) Limited, issuing bothordinary shares

Common stock is a form of corporate equity ownership, a type of security. The terms voting share and ordinary share are also used frequently outside of the United States. They are known as equity shares or ordinary shares in the UK and other Comm ...

and debentures, with the objective of paying down the debts incurred in its rapid expansion. It had already achieved market dominance

Market dominance describes when a firm can control markets. A dominant firm possesses the power to affect competition and influence market price. A firms' dominance is a measure of the power of a brand, product, service, or firm, relative to c ...

in Australia, within three years of starting local production.

'Davis Gelatine' became a famous brand. The company promoted use of gelatin through recipes for 'The Australian Women's Weekly

''The Australian Women's Weekly'', sometimes known as simply ''The Weekly'', is an Australian monthly women's magazine published by Mercury Capital in Sydney. For many years it was the number one magazine in Australia before being outsold by ...

. Davis Gelatine almost certainly took the concept of 'Dainty Dishes''Johnstown, New York

Johnstown is a city in and the county seat of Fulton County in the U.S. state of New York. The city was named after its founder, Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Province of New York and a major general during the Sev ...

.''

The Davis Gelatine recipe booklets were published in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa, and from 1932 in Great Britain. There were nine editions compiled between 1922 and 1947; a complete revision was made in 1949. The booklets would eventually be printed in five languages; English, French, German, Afrikaans and Portuguese. Over the years that the booklets were published, the total number printed was well in excess of one million copies.

As the main manufacturer of gelatin in Australia, the company also benefited from the demand for gelatin generated by other manufacturers. The main ingredients of jelly crystals—such as Aeroplane Jelly

Aeroplane Jelly is a jelly brand in Australia created in 1927 by Bert Appleroth. Appleroth's backyard business, Traders Pty Ltd, became one of Australia's largest family-operated food manufacturers and was sold to McCormick Foods Australia, ...

—were dry granular gelatin and sugar, with flavouring, and used in the commercial production of ice cream

Ice cream is a sweetened frozen food typically eaten as a snack or dessert. It may be made from milk or cream and is flavoured with a sweetener, either sugar or an alternative, and a spice, such as cocoa or vanilla, or with fruit such as ...

. Dry gelatin was added when canning some products, particularly canned hams. Gelatin was also used in the production of photographic film. It was a material with many uses.Factory at Botany

Davis set out to create a model factory at Botany. It was surrounded by park-like gardens and included facilities for workers, such as abowling green

A bowling green is a finely laid, close-mown and rolled stretch of turf for playing the game of bowls.

Before 1830, when Edwin Beard Budding of Thrupp, near Stroud, UK, invented the lawnmower, lawns were often kept cropped by grazing sheep ...

and tennis courts.

The plant consumed four million gallons of water per week, drawn from the Botany Swamps

The Botany Water Reserves are a heritage-listed former water supply system and now parkland and golf course at 1024 Botany Road, Mascot, Bayside Council, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by City Engineers, W. B. Rider, E. Bel ...

aquifer and then clarified and filtered. The raw materials were pieces of animal skin that could not be used in the process of tanning

Tanning may refer to:

*Tanning (leather), treating animal skins to produce leather

*Sun tanning, using the sun to darken pale skin

**Indoor tanning, the use of artificial light in place of the sun

**Sunless tanning, application of a stain or dye t ...

and small sinews, both by-products of the meat industry. The process included acid baths, washing, and lime pits. Last was a drying room, reported to be like a 'tame hurricane', where the water content of sheets of gelatin were dried, reducing their thickness from 3/8 inch to 1/32 inch.

The plant was competitive, despite high wages, evidence that Australia had a competitive advantage in the production of gelatin, on a very large scale. By 1928, the Botany plant had trebled in size and was the largest in the world. The combined output of Davis Gelatine plants accounted for 10% of world production in that year.

Marriage and personal life

Davis married in Sydney, on the same day that he had bought the land for the Botany factory. His wife was Elizabeth Eileen Schischka, (1889 – 1981)—known as Eileen—the Auckland-born daughter of a friend of his mother, who had come with him to Sydney. Her family had Bohemian ancestry. Although he was keen on travel, gardening and motoring, as recreational pursuits, his business interests were his life. Davis was hearing-impaired and that made him reticent in company. He wore an early type of hearing aid. The couple had no children. From 1917 to 1930 they lived in a house adjacent to the factory at Botany. In 1930, they moved to a house in the harbourside suburb ofVaucluse

Vaucluse (; oc, Vauclusa, label= Provençal or ) is a department in the southeastern French region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. It had a population of 561,469 as of 2019.

However, his life remained dominated by business, as he became involved in other areas of activity that were important to Australia’s response to the deteriorating international situation during the 1930s and the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, Australia was almost entirely dependent for its petroleum supplies on imports; at best there was some local refining of imported crude oil. There had been production of oil from

In the 1930s, Australia was almost entirely dependent for its petroleum supplies on imports; at best there was some local refining of imported crude oil. There had been production of oil from  Earlier proposals for restarting shale oil production had been based on resurrecting Newnes, by bringing shale from the

Earlier proposals for restarting shale oil production had been based on resurrecting Newnes, by bringing shale from the

Davis, Sir George Francis (1883–1947)

by R. Ian Jack - Australian Dictionary of Biography entry {{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, George Francis 1883 births 1947 deaths Australian manufacturing businesspeople Australian Knights Bachelor 20th-century Australian businesspeople

Cockatoo Island Dockyard

Possessed of seemingly boundless energy and initiative, Davis formed a syndicate of business interests to take out a lease on the moribundCockatoo Island Dockyard

The Cockatoo Island Dockyard was a major dockyard in Sydney, Australia, based on Cockatoo Island. The dockyard was established in 1857 to maintain Royal Navy warships. It later built and repaired military and battle ships, and played a key role ...

, The yard had been badly affected by a High Court decision, in 1929, which effectively precluded the Commonwealth government-owned dockyard from tendering for work against private companies, and by the effects of the Great Depression. In 1933, Davis formed a new company Cockatoo Docks & Engineering Co. Ltd to run the yard.

He turned the dockyard operations around and expanded the range of services it could provide, in time for it to become a vital part of the war effort. At its peak, the yard employed 3,500 workers, ten times the number that had been employed when the new company took over. Following the Fall of Singapore

The Fall of Singapore, also known as the Battle of Singapore,; ta, சிங்கப்பூரின் வீழ்ச்சி; ja, シンガポールの戦い took place in the South–East Asian theatre of the Pacific War. The Empire o ...

, it became the main ship repair base in the South Pacific for a period; 19 new ships were built there and major repairs undertaken on 40 Allied warships.

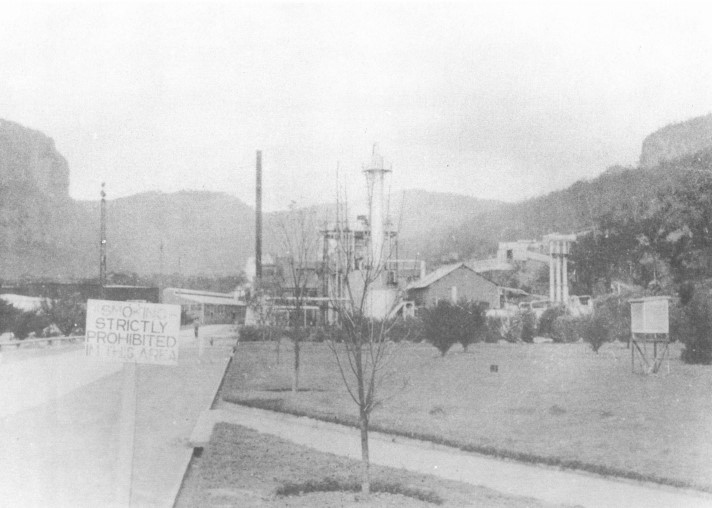

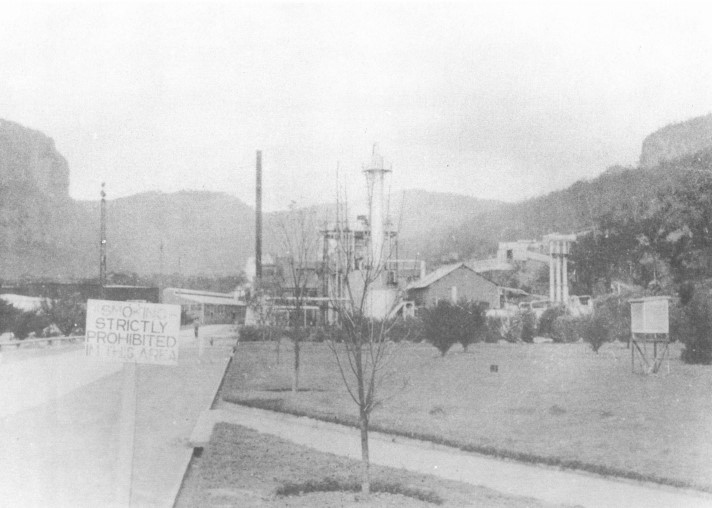

Glen Davis and shale oil

The revival of the dockyard had brought Davis to the attention of the Commonwealth and New South Wales governments, as a person who could tackle something new and get it done, quickly and effectively. However, both the governments at the time were controlled by theUnited Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

—a political party that favoured private enterprise as opposed to government ownership of industries—and rightly or wrongly, Davis was seen as being associated with that side of politics. In the 1930s, Australia was almost entirely dependent for its petroleum supplies on imports; at best there was some local refining of imported crude oil. There had been production of oil from

In the 1930s, Australia was almost entirely dependent for its petroleum supplies on imports; at best there was some local refining of imported crude oil. There had been production of oil from oil shale

Oil shale is an organic-rich fine-grained sedimentary rock containing kerogen (a solid mixture of organic chemical compounds) from which liquid hydrocarbons can be produced. In addition to kerogen, general composition of oil shales constitut ...

, but this had ceased. The oil shale of New South Wales is particularly rich in oil content. The genesis of a revival of the shale oil industry was partially due a need for a secure source of oil in wartime, and partially to provide employment for unemployed miners on the Western coalfield. These dual objectives, efficient local oil production and employment creation, would not always align in their outcomes.

A public notice in the ''Commonwealth of Australia Gazette

The ''Commonwealth of Australia Gazette'' is a printed publication of the Commonwealth Government of Australia, and serves as the official medium by which decisions of the executive arm of government, as distinct from legislature and judiciary, ...

'', on 28 May 1936, invited offers for developing the oil industry in the Glen Davis area. Davis responded to this invitation and the result was the agreement ratified in the ''National Oil Proprietary Limited Agreement Ratification Act 1937'', an act of the NSW Parliament.

Davis withdrew almost entirely from his other activities, and threw himself into the task of creating a modern shale oil industry. It was later said of him by Bertram Stevens that, "''the Lyons Administration and my own, asked him to shoulder this further national obligation at Glen Davis. He promptly agreed, and without stint gave to it his time and boundless energy and much of his resources taking from it not one penny of reward''."

He made a tour of existing plants in other countries, visiting Scotland, Germany, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

and the United States, over eleven months. He returned in January 1938. Samples of oil shale were sent to Estonia and the United States for trial processing into refined petroleum products.

A new company, National Oil Proprietary Ltd, had been set up to build and run the operations. The amount of capital for the company, £500,000, which would later prove to be inadequate, had been based on estimates made by the government. Davis contributed £166,000 and Commonwealth Government £344,000 (together the capital of £500,000), and the New South Wales Government provided £166,000 secured by debentures. Earlier proposals for restarting shale oil production had been based on resurrecting Newnes, by bringing shale from the

Earlier proposals for restarting shale oil production had been based on resurrecting Newnes, by bringing shale from the Capertee Valley

The Capertee Valley (pronounced Kay-per-tee) is a large canyon in New South Wales, Australia, north-west of Sydney that is noted to be the second widest of any canyon in the world, exceeding The Grand Canyon. It is located kilometres north-we ...

, through a new mine tunnel between the Wolgan and Capertee valleys and processing the shale at the site of the old works, previously operated by Commonwealth Oil Corporation Commonwealth Oil Corporation Limited was an English-owned Australian company associated with the production and refining of petroleum products derived from oil shale, during the early years of the 20th century. It is associated with Newnes, Hartley ...

. Davis chose not to re-establish operations at Newnes but instead to build an entirely new plant in the relatively remote Capertee Valley. The refined fuel would be carried via a new pipeline running over a saddle from the Capertee Valley into the Wolgan Valley

Wolgan Valley is a small valley located along the Wolgan River in the Lithgow Region of New South Wales, Australia. The valley is located approximately north of Lithgow and 150 kilometres north-west of Sydney. Accessible by thWolgan Valley Di ...

, and then mainly following the route of the old Wolgan Valley Railway

The Newnes railway line (also called Wolgan Valley Railway) is a closed and dismantled railway line in New South Wales, Australia. The line ran for from the Main Western line to the township of Newnes. Along the way, it passed through a tunn ...

to new storage tanks at Newnes Junction. The old railway line was lifted, with some of the old bullhead rails being reused as supports for the pipeline.

Originally, Davis's plan was to use Estonian-made tunnel kilns, but as costs rose and war seemed imminent, a decision was made to rebuild retorts at Glen Davis, using designs and reused materials from the old retorts at Newnes; that decision resulted in an expensive and protracted relocation exercise, and old retort technology. Otherwise, Davis built a very modern plant, with a highly mechanised shale mine that promised to produce at a high enough rate to make the plant economically viable.

Work on the new plant began in 1938, but the first oil was not produced at the remotely-situated plant until January 1940, by which time Australia was at war. The plant had cost £1,300,000, and more capital was raised from shareholders, with the Commonwealth Government providing more funds in the form of a £225,000 loan.

The initial rate of production was disappointing. In 1941, the UAP lost power to the Labor Party. The incoming Curtin government was fearful for its investment and anxious about the precious oil supply, and its Minister for Supply and Development, Jack Beasley

John Albert Beasley (9 November 1895 – 2 September 1949) was an Australian politician who was a member of the House of Representatives from 1928 to 1946. He served in the Australian War Cabinet from 1941 to 1946, and was a government ministe ...

, moved to take control of operations at Glen Davis.

For his role in establishing the industry, Davis had been knighted in January 1941. After December 1941, the by then Sir George Davis remained chairman of the board of National Oil but was effectively sidelined, as the board consisted largely of government appointees and he had lost his position as Managing Director. He resigned from the board in October 1942. He would devote most of his time thereafter to the Davis Gelatine company and the dockyard.

To house the workers of the oil shale works, a new town was planned by the New South Wales Government. Its plan would be influenced by the ‘Garden City’ movement, and was very much in line with Davis’s own view on ideal workers communities. However, in its early years, conditions at the remotely-situated town site were primitive.

Probably following the pattern set by nearby Glen Alice the new town was named Glen Davis, after Davis himself.

Later life, death and legacy

Following the end of the Second World War, Davis and his wife left Australia for ten months—up to the end of December 1946—during which time they visited overseas branches of his companies—in England, South Africa, Canada, and America—and also visited Norway and Sweden. It is probable that during this time Davis discussed the sale of Cockatoo Dockyard & Engineering with its eventual buyer,Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public i ...

.

Davis died at home of cardiovascular disease on 13 July 1947, after being ill for some weeks. He was survived by his wife, who died in 1981. At the time of his death, he was chairman of Davis Gelatine (Aust.) Pty. Ltd., and its associated companies, Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Co. Pty. Ltd. Mount Frome Lime Co. Pty. Ltd., and Animal Health Products Pty. Ltd.; and a director of Mercantile Mutual Insurance Company Ltd. and Alluvial Prospectors Company Ltd.

Cockatoo Dockyard and Engineering was taken over by Vickers in 1947, having played a vital role during the Second World War. It was Davis who had saved it from terminal decline, during the 1930s, and expanded it to allow it to be such an important wartime facility. Following a change of government policy in 1972, the dockyard entered a long decline. It finally closed at the end of 1991. Cockatoo Island is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

.

Davis did not live to see the bitter end of his vision for Glen Davis. The government's intervention at Glen Davis was not successful, despite an expansion in 1946. Never profitable, the Glen Davis Shale Oil Works was closed in May 1952, once its accumulated losses had exceeded the value of capital and loans. Glen Davis soon became virtually a ghost town, declining from a population of 2000 at its peak to only 115, including the surrounding area, in 2016. The ruins of the old works are now a minor tourist attraction.

The Davis Gelatine company remained in family hands, under the leadership of one of Charles Christopher ('Chris') Davis's children, Malcolm Chris Davis (1917–2009), as a publicly-listed company, Davis Gelatine Consolidated Limited. Malcolm Davis retired in 1978, after having expanded the business into areas such as sealants, paper conversion, food stabilisers and emulsifiers, PVC plastics compounding, gummed tapes and paper coating, wine production, and food essences and flavourings. He wrote a history of the company, ''Davis Gelatine: An Outline History'', published in 1993. The company became a part of Fielder Gillespie in 1983. The factory at Botany was only closed in 1990. Its site was reused mainly for warehouses, and only a small part of the once extensive gardens remain. Gelatin sold under the brand name, Davis Gelatine, is still made at a modern plant in Beaudesert, Queensland, the sole remaining gelatin plant in Australasia, which is owned by DGF Stoess AG of Germany.

There was still, in 2022, a thriving market in second-hand copies of Davis Dainty Dishes''References

External links

Davis, Sir George Francis (1883–1947)

by R. Ian Jack - Australian Dictionary of Biography entry {{DEFAULTSORT:Davis, George Francis 1883 births 1947 deaths Australian manufacturing businesspeople Australian Knights Bachelor 20th-century Australian businesspeople