David Margesson, 1st Viscount Margesson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry David Reginald Margesson, 1st Viscount Margesson, PC (26 July 1890 – 24 December 1965) was a British

Many were surprised that Churchill retained Margesson as Chief Whip, little realising that there was no personal animosity between the two and that Churchill would have had less regard for Margesson if he had not carried out his functions as Chief Whip. Margesson proved a useful buttress of support as Churchill consolidated his position in government.

Margesson, who was living at the

Many were surprised that Churchill retained Margesson as Chief Whip, little realising that there was no personal animosity between the two and that Churchill would have had less regard for Margesson if he had not carried out his functions as Chief Whip. Margesson proved a useful buttress of support as Churchill consolidated his position in government.

Margesson, who was living at the

The Papers of 1st Viscount Margesson of Rugby

held at

Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

politician, most popularly remembered for his tenure as Government Chief Whip

The Chief Whip is a political leader whose task is to enforce the whipping system, which aims to ensure that legislators who are members of a political party attend and vote on legislation as the party leadership prescribes.

United Kingdom

I ...

in the 1930s. His reputation was of a stern disciplinarian who was one of the harshest and most effective whips

A whip is a blunt weapon or implement used in a striking motion to create sound or pain. Whips can be used for flagellation against humans or animals to exert control through pain compliance or fear of pain, or be used as an audible cue thro ...

. His sense of the popular mood led him know when to sacrifice unpopular ministers. He protected the appeasement

Appeasement, in an International relations, international context, is a diplomacy, diplomatic negotiation policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power (international relations), power with intention t ...

-supporting government as long as he could.

However, some argue that there were weaknesses of his system because of the number of high-profile rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

s during his tenure.

Background and education

Margesson was the third child and elder son of Sir Mortimer Margesson and Lady Isabel, daughter of Frederick Hobart-Hampden, Lord Hobart, and sister of the 7th Earl of Buckinghamshire. He grew up inWorcestershire

Worcestershire ( , ; written abbreviation: Worcs) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It is bordered by Shropshire, Staffordshire, and the West Midlands (county), West ...

and was educated at Harrow School

Harrow School () is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English boarding school for boys) in Harrow on the Hill, Greater London, England. The school was founded in 1572 by John Lyon (school founder), John Lyon, a local landowner an ...

and Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

. He did not complete his degree, choosing instead to seek his fortune in the United States of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 contiguo ...

. Margesson volunteered at the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in 1914 and served as an adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

in the 11th Hussars

The 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army established in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the First World War and Second World War but then amalgamated with the 10th Royal Hussars (Pri ...

.

Early political career, 1922–1931

After the war, Margesson entered politics at the suggestion of Lord Lee of Fareham. In the 1922 general election, he was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Upton. Very soon after his election, he was appointed Parliamentary Private Secretary to theMinister of Labour Minister of labour (in British English) or labor (in American English) is typically a cabinet-level position with portfolio responsibility for setting national labour standards, labour dispute mechanisms, employment, workforce participation, traini ...

, Anderson Montague-Barlow. In the 1923 general election, he lost his seat, but at the 1924 general election, he returned to Parliament for Rugby, the seat for which he would sit for the next eighteen years. He defeated future Liberal National leader Ernest Brown in the process.

Margesson was appointed Assistant Government Whip. Two years later, he became a more senior whip with the title Junior Lord of the Treasury until the Conservatives' defeat, in the 1929 general election. In August 1931, he was reappointed to the same position upon the formation of the National Government.

Government Chief Whip, 1931–1940

Following the November 1931 general election, he was promoted to the senior position ofParliamentary Secretary to the Treasury

The Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury is the official title of the most senior whip of the governing party in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Today, any official links between the Treasury and this office are nominal and the title ...

(Government Chief Whip). Margesson's position was in many ways unprecedented, having the task of keeping in power a grouping composed of the Conservatives, National Labour and two groups of Liberals (the official Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

and the Liberal National Party) all behind a single government that sought to stand above partisan politics. With the government commanding the support of 556 MPs, as opposed to just 58 opposition members, his main task was to ensure that the government stayed together and was able to pass contentious legislation without risking a major breach within the government.

That proved tricky several times, as different sections of the National combination came to denounce areas of government policy. Margesson adopted a method of strong disciplinarianism combined with selective use of patronage and the social effect of ostracism to secure every vote possible. An example of his methods was his letter to the House of Commons' youngest member, the future minister John Profumo

John Dennis Profumo ( ; 30 January 1915 – 9 March 2006) was a British politician whose career ended in 1963 after a sexual relationship with the 19-year-old model Christine Keeler in 1961. The scandal, which became known as the Profumo affai ...

, after the Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the ''Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

, in which Profumo had opposed other Conservatives. Margesson's letter included the following extraordinary passage: "And I can tell you this, you utterly contemptible little shit. On every morning that you wake up for the rest of your life you will be ashamed of what you did last night." On that occasion, his methods failed.

Despite such behaviour, Margesson remained a much-liked individual, with many members expressing personal admiration for him. Away from his duties he was known to be quite sociable, and within the parliamentary party; few bore him ill. However, a major faultline lay over the question of introducing protective tariffs

Protective tariffs are tariffs that are enacted with the aim of protecting a domestic Industry (economics), industry. They aim to make imported goods cost more than equivalent goods produced domestically, thereby causing sales of domestically pr ...

on imports as a prelude to negotiating a customs union

A customs union is generally defined as a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff.GATTArticle 24 s. 8 (a)

Customs unions are established through trade pacts where the participant countries set u ...

within the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

. The proposed policy had deeply divided the Conservatives over the previous 30 years, but by then, they, with most of the National Labour and Liberal National members of the government, had become in favour of the policy during the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

.

However the Liberal Party remained committed to the principle of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

and were deeply reluctant to compromise. Whilst the Liberals themselves barely commanded the support of 33 MPs, they were one of only two parties in the government with a long independent history, and there were fears that their withdrawal would turn the National Government into a mere Conservative rump, something that National Labour Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald

James Ramsay MacDonald (; 12 October 18669 November 1937) was a British statesman and politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The first two of his governments belonged to the Labour Party (UK), Labour Party, where he led ...

wished to avoid.

At one stage, it was agreed that members of the cabinet would suspend the principle of cabinet collective responsibility

Cabinet collective responsibility, also known as collective ministerial responsibility, is a constitutional convention in parliamentary systems and a cornerstone of the Westminster system of government, that members of the cabinet must publicly ...

and agree to differ on tariffs.

Matters were complicated again by the question of Cabinet appointments. When the Liberal President of the Board of Education

The secretary of state for education, also referred to as the education secretary, is a Secretary of State (United Kingdom), secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, responsible for the work of the Department for Education. ...

Sir Donald Maclean died, Margesson insisted that to appoint another Liberal, merely on the basis of party balance, would inflame tensions in Conservative MPs, could lead to a poor appointment and would maintain an imbalance, the Liberals having one more Cabinet minister than the Liberal Nationals did despite the latter having two more MPs. National Labour Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State (United Kingdom), Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and abov ...

Lord Snowden was increasingly siding with the Liberals on all key divisions, thus providing a surrogate. The appointment of the Conservative Lord Irwin upset the Liberals, who had no promise that the next Cabinet vacancy would be filled by a Liberal.

In the summer of 1932, the Ottawa Agreement was negotiated between the dominions, and free trade seemed a dead cause within government. In September, the Liberals resigned their ministerial offices but did not withdraw complete support for the government until the following November. However the National Government did not break up, as the remaining National Labour and Liberal National elements remained in government.

In 1933, Margesson was appointed to the Privy Council.

In 1935, the Government came under fire from the Diehard Conservative wing of the Conservative Party over plans to implement the Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act 1935 (25 & 26 Geo. 5. c. 42) was an Act of Parliament (UK), act passed by the British Parliament that originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest act that the British Parliament ever enact ...

, which would grant India more autonomy. The policy was widely felt to be a hangover from the previous Labour government and one that few Conservative governments would have implemented. Many believed that the plan would not have been pursued except for both a desire to prove the government's nonpartisan credentials and Conservative leader Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

's determination to implement the policy. For some, the question of the success of the policy became a question of the survival of the National Government. Opponents to Indian Home Rule found several spokespersons, most notably Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

, and they harried the government at every stage, with nearly one hundred Conservative MPs voting against the third reading of the Bill, the highest number of Conservatives to vote against a three-line whip in the twentieth century. Still, the Bill passed easily.

Margesson was retained as Chief Whip when Baldwin became Prime Minister in June 1935 but had to face further rifts in the party over foreign policy and other matters. The government's majority was cut to 250 in the November 1935 general election. In December, the leaking of the proposed Hoare-Laval Plan to grant two-thirds of Abyssinia

Abyssinia (; also known as Abyssinie, Abissinia, Habessinien, or Al-Habash) was an ancient region in the Horn of Africa situated in the northern highlands of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea.Sven Rubenson, The survival of Ethiopian independence, ...

to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

outraged some Conservative MPs. Margesson's reading of the mood led to the Foreign Secretary Samuel Hoare being dropped from the government to soothe feelings and keep the government in power.

The late 1930s were a turbulent time within the National Government, with rebellions over foreign policy, over unemployment, over agriculture and other matters routinely threatened to rock the government. Margesson was instrumental in heading off many of the rebellions and limiting damage caused by others. He was instrumental in warding these off for Baldwin and then Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from ...

. However, a well of discontent with the government's foreign policy grew, especially after Britain entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Eight months into the conflict, severe reverses in the Norwegian campaign led to the two-day "Norway Debate

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the ''Hansard'' parliamentary archiv ...

" of 7 and 8 May 1940 in which the government came under severe criticism from its own supporters and witnessed a massive rebellion on a motion of confidence

A motion or vote of no confidence (or the inverse, a motion or vote of confidence) is a motion and corresponding vote thereon in a deliberative assembly (usually a legislative body) as to whether an officer (typically an executive) is deemed fi ...

. The government maintained a majority, but Margesson's soundings revealed that that majority was imperilled unless the political composition of the government was widened. When Chamberlain realised that he was unable to do so, he resigned and was succeeded by Churchill.

Margesson was referred to in the book "Guilty Men

''Guilty Men'' is a British polemical book written under the pseudonym "Cato" that was published in July 1940, after the failure of British forces to prevent the defeat and occupation of Norway and France by Nazi Germany. It attacked fifteen publ ...

" by Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British politician who was Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition (United Kingdom), Leader of the Opposition from 1980 to 1983. Foot beg ...

, Frank Owen and Peter Howard (writing under the pseudonym "Cato"), published in 1940 as an attack on public figures for their failure to re-arm and their appeasement of Nazi Germany.

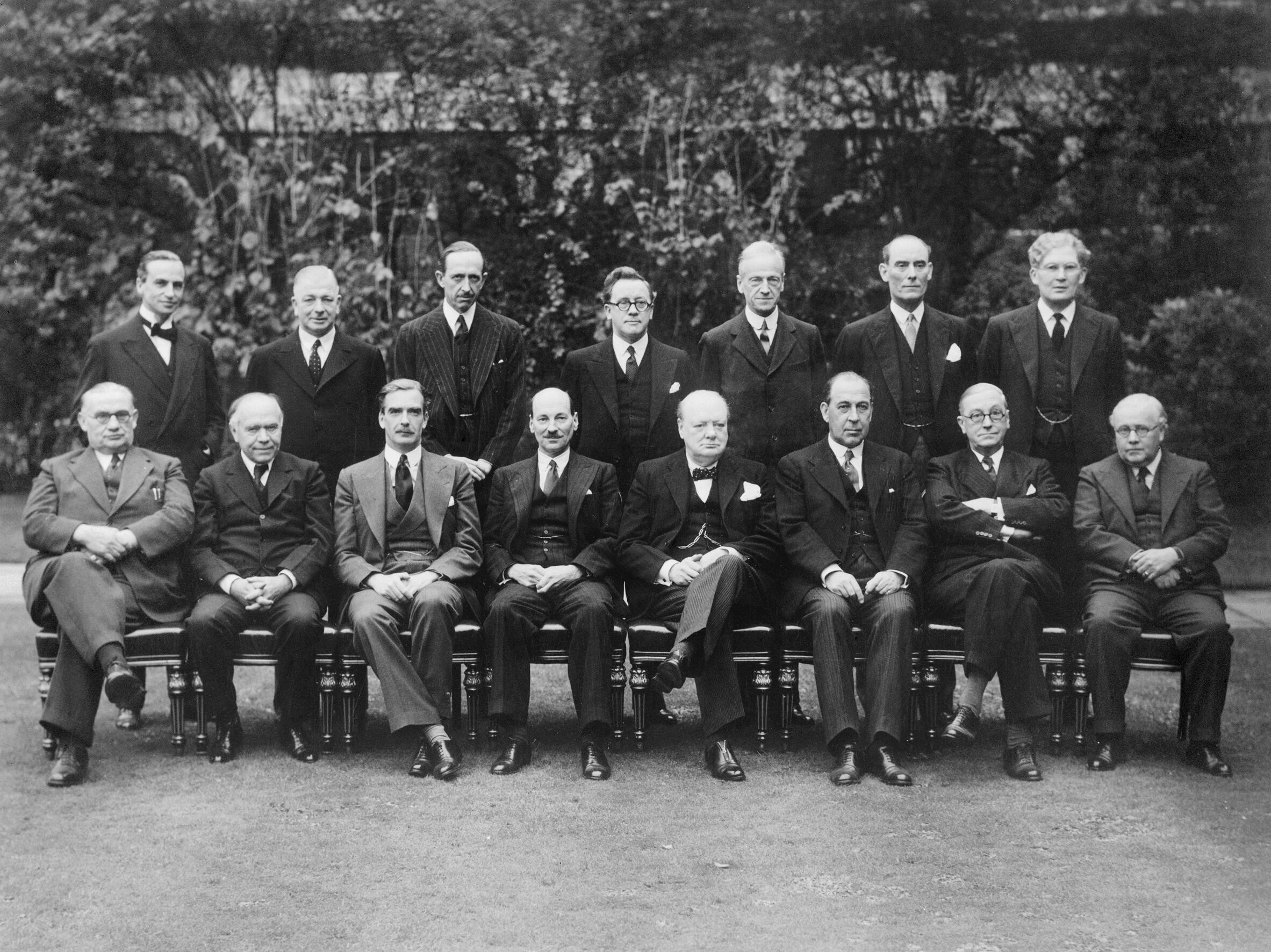

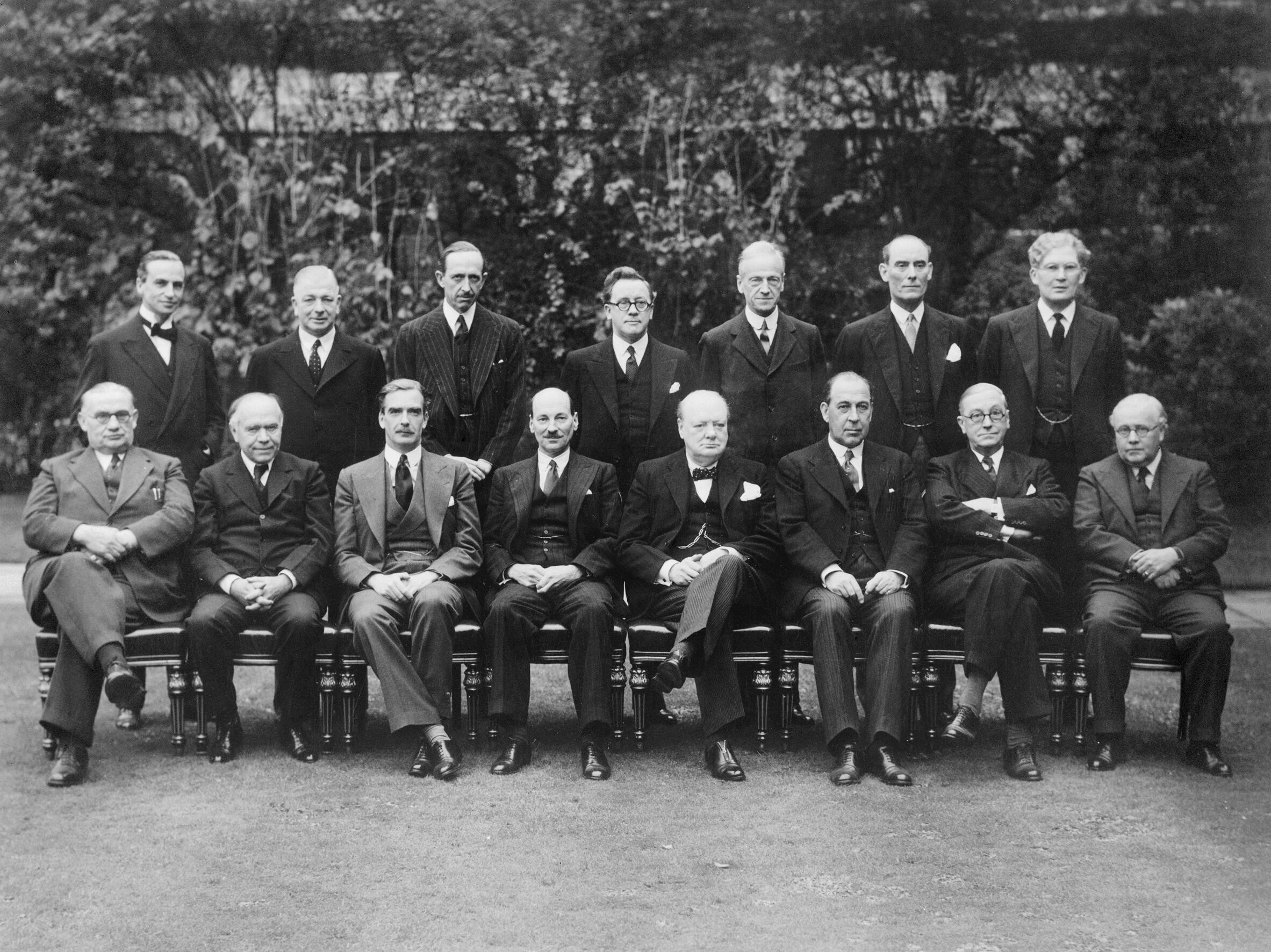

Secretary of State for War, 1940–1942

Many were surprised that Churchill retained Margesson as Chief Whip, little realising that there was no personal animosity between the two and that Churchill would have had less regard for Margesson if he had not carried out his functions as Chief Whip. Margesson proved a useful buttress of support as Churchill consolidated his position in government.

Margesson, who was living at the

Many were surprised that Churchill retained Margesson as Chief Whip, little realising that there was no personal animosity between the two and that Churchill would have had less regard for Margesson if he had not carried out his functions as Chief Whip. Margesson proved a useful buttress of support as Churchill consolidated his position in government.

Margesson, who was living at the Carlton Club

The Carlton Club is a private members' club in the St James's area of London, England. It was the original home of the Conservative Party before the creation of Conservative Central Office. Membership of the club is by nomination and elect ...

since his recent divorce, was present when it was bombed by the Luftwaffe on 14 October 1940. He was left homeless and had to sleep for a time on a makeshift bed in the underground Cabinet Annexe.

When, at the end of 1940, the position of Secretary of State for War

The secretary of state for war, commonly called the war secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The secretary of state for war headed the War Offic ...

fell vacant, Margesson was promoted to it. Margesson proved competent and efficient, but in February 1942, Britain suffered severe military setbacks, including the loss of Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

. Churchill was forced to make changes to his ministerial team and find scapegoats for the disasters. Margesson was dropped and replaced by his own Permanent Under-Secretary

A permanent under-secretary of state, known informally as a permanent secretary, is the most senior civil servant of a ministry in the United Kingdom, charged with running the department on a day-to-day basis. Permanent secretaries are appointe ...

P. J. Grigg, an unprecedented move. Margesson was first told of the change by Grigg himself but accepted his fate as necessary for the government's future. Later that year, he was made Viscount Margesson, of Rugby in the County of Warwick. His political influence waned sharply. He subsequently worked in the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

.

Family

Margesson married Frances, the half-sister of Alberta Montagu, Countess of Sandwich and daughter of Francis Howard Leggett and Betty Leggett, in 1916. They had one son and two daughters but were divorced in 1940. Their second daughter, the Hon. Mary, married Lord Charteris of Amisfield. Lord Margesson died inthe Bahamas

The Bahamas, officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic and island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the Atlantic Ocean. It contains 97 per cent of the archipelago's land area and 88 per cent of ...

in December 1965, aged 75, and was succeeded in the viscountcy by his only son, Francis.

Arms

Book

*References

External links

* *The Papers of 1st Viscount Margesson of Rugby

held at

Churchill Archives Centre

The Churchill Archives Centre (CAC) at Churchill College at the University of Cambridge is one of the largest repositories in the United Kingdom for the preservation and study of modern personal papers. It is best known for housing the papers ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Margesson, David 1st Viscount Margesson

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies

Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Ministers in the Chamberlain peacetime government, 1937–1939

Ministers in the Chamberlain wartime government, 1939–1940

Ministers in the Churchill wartime government, 1940–1945

Viscounts created by George VI

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

Margesson, David, 1st Viscount

UK MPs who were granted peerages

War Office personnel in World War II