David Kirkaldy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

David Kirkaldy (1820–1897) was a Scottish engineer who pioneered the testing of materials as a service to engineers during the Victorian period. He established a test house in

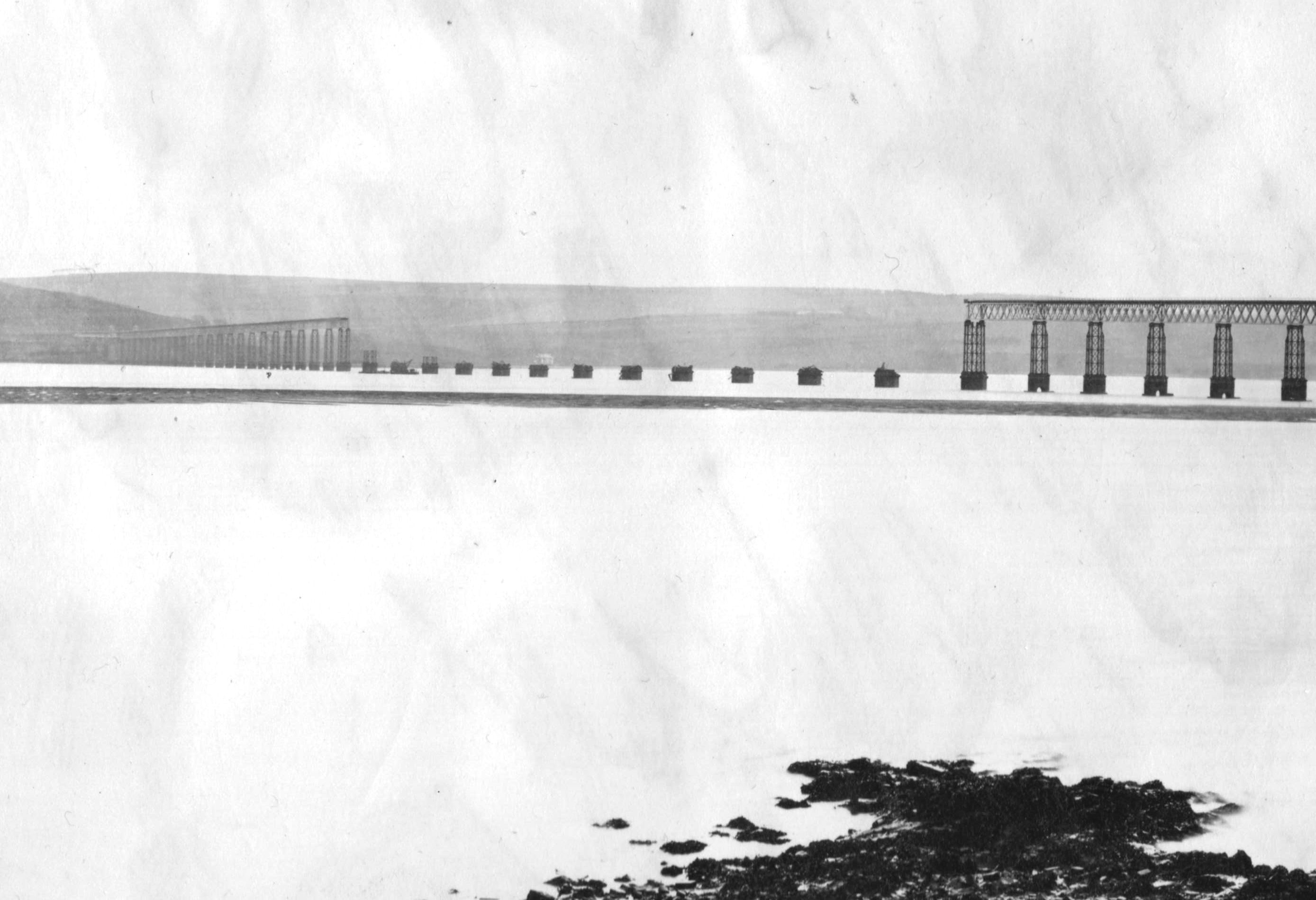

He famously tested many samples taken from the first Tay railway bridge for the official Inquiry on the Tay Bridge Disaster. He confirmed that the wrought iron tie bars failed at their connections to the cast iron columns of the bridge, when he tested intact tie bars with complete lugs still attached. The attachments were cast iron lugs which fractured at the bolt holes, and numerous fractured lugs were found after the disaster lying on the piers. The critical strengthening elements were much weaker than had been supposed by Thomas Bouch, the engineer of the first bridge. They failed at about 20 tons tensile load rather than the specified 60 tons, and were a prime cause of the collapse of the bridge on 28 December 1879. Since he tested several samples of each of the lower and upper lugs, he was able to show that they exhibited a range of strengths, the lowest results being caused by defects like blow holes in the cast metal. Thus some of the upper lugs were actually weaker than the strongest lower lugs, an observation confirmed by damage shown on the remains left on the piers after the disaster. He tested the wrought iron tie bars themselves, and they proved tough, as specified, although only slightly stronger than the cast iron lugs to which they were attached. The high girders were also made of wrought iron and had a very high tensile strength. They were found after the accident at the bottom of the Tay estuary and relatively little damaged compared with the cast iron columns which supported them. Some were reused in local houses, and when they were demolished in the 1960s, some were removed to the

He famously tested many samples taken from the first Tay railway bridge for the official Inquiry on the Tay Bridge Disaster. He confirmed that the wrought iron tie bars failed at their connections to the cast iron columns of the bridge, when he tested intact tie bars with complete lugs still attached. The attachments were cast iron lugs which fractured at the bolt holes, and numerous fractured lugs were found after the disaster lying on the piers. The critical strengthening elements were much weaker than had been supposed by Thomas Bouch, the engineer of the first bridge. They failed at about 20 tons tensile load rather than the specified 60 tons, and were a prime cause of the collapse of the bridge on 28 December 1879. Since he tested several samples of each of the lower and upper lugs, he was able to show that they exhibited a range of strengths, the lowest results being caused by defects like blow holes in the cast metal. Thus some of the upper lugs were actually weaker than the strongest lower lugs, an observation confirmed by damage shown on the remains left on the piers after the disaster. He tested the wrought iron tie bars themselves, and they proved tough, as specified, although only slightly stronger than the cast iron lugs to which they were attached. The high girders were also made of wrought iron and had a very high tensile strength. They were found after the accident at the bottom of the Tay estuary and relatively little damaged compared with the cast iron columns which supported them. Some were reused in local houses, and when they were demolished in the 1960s, some were removed to the

Brief biography of KirkaldyKirkaldy museumKirkaldy museum locationKirkaldy's book on Iron and steel

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kirkaldy, David People educated at the High School of Dundee 1820 births 1897 deaths Burials at Highgate Cemetery Scottish inventors Scottish engineers Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Engineers from Dundee 19th-century Scottish engineers 19th-century Scottish businesspeople Scottish company founders

Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, London and built a large hydraulic tensile test machine, or tensometer for examining the mechanical properties of components, such as their tensile strength and tensile modulus or stiffness

Stiffness is the extent to which an object resists deformation in response to an applied force.

The complementary concept is flexibility or pliability: the more flexible an object is, the less stiff it is.

Calculations

The stiffness, k, of a b ...

.

Career

David Kirkaldy was born in Mayfield east ofDundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

in Scotland in 1820. He worked at Robert Napier’s Vulcan Foundry Works in Glasgow, and moved from workshop to drawing office. As a result of the industrial revolution, new materials were being developed such as steel

Steel is an alloy made up of iron with added carbon to improve its strength and fracture resistance compared to other forms of iron. Many other elements may be present or added. Stainless steels that are corrosion- and oxidation-resistant ty ...

to replace cast iron and wrought iron. The properties of these materials were not well understood. In conjunction with his work for Napier and Sons, Kirkaldy undertook a long series of tensile load tests between 1858 and 1861. He published his ''Results of an Experimental Inquiry into the Comparative Tensile Strength and other properties of various kinds of Wrought-Iron and Steel'' in 1862.

Testing materials

Kirkaldy left Napier in 1861 and over the next two and a half years studied existing testing techniques and designed his own testing machine. Entirely at his own expense, he commissioned this machine from the Leeds firm of Greenwood & Batley, closely supervising its production. Aggrieved over the slow rate of manufacture, after fifteen months he had it delivered to London still unfinished, in September 1865. The testing machine is 47 feet 7 inches long, weighs some 116 tons, and was designed to work horizontally, the load applied by a hydraulic cylinder and ram.Testing house

He set up business in Southwark in 1866, performing tests for external clients on materials used in engineered structures such as bridges. The business moved to a nearby purpose-built building at 99 Southwark Street, London in 1874. The present ground floor of the building is now theKirkaldy Testing Museum

The Kirkaldy Testing Museum is a museum in Southwark, south London, England, in David Kirkaldy's former testing works. It houses Kirkaldy's huge testing machine, and many smaller more modern machines. It is open on the first Sunday of each month ...

, with many of his machines still there and in working order, including the original 1865 testing machine. The famous inscription above the door reads ''Facts not Opinions''. With the many failed products either from his own tests or collected on site, he opened a "Black Museum" of failed products and components on the top floor of the building, but it was destroyed in the London Blitz of 1940. Fractured lug samples from the Tay Bridge disaster were probably stored and exhibited in the museum.

He developed ways of examining the microstructures of materials using a simple optical microscope after polishing and etching specimens taken from components.

Tay Bridge Disaster

Royal Museum of Scotland

The National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, Scotland, was formed in 2006 with the merger of the new Museum of Scotland, with collections relating to Scottish antiquities, culture and history, and the adjacent Royal Scottish Museum (opened in ...

in Edinburgh, where they are on public display.

Death

He died on 25 January 1897 and is buried in a family grave on the eastern side of Highgate Cemetery. He was succeeded by his son in the family business.Honours

He was inducted into the Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame in 2023.Bibliography

* WG Kirkaldy, ''Experimental Inquiry into the Comparative Tensile Strength and other properties of various kinds of Wrought-Iron and Steel'' (1862).References

* Denis Smith: David Kirkaldy (1820-1897) and engineering Materials Testing, ''Transactions of the Newcomen Society'' 53,1 (1980): 49ff. * Peter R Lewis, ''Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: re-investigating the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879'', Tempus (2004) * Frances Robertson, David Kirkaldy (1820-1897) and his museum of destruction: the visual dilemmas of an engineer as man of science. ''Endeavour'', 37,3 (2013) 125-132.External links

*Brief biography of Kirkaldy

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kirkaldy, David People educated at the High School of Dundee 1820 births 1897 deaths Burials at Highgate Cemetery Scottish inventors Scottish engineers Scottish Engineering Hall of Fame inductees Engineers from Dundee 19th-century Scottish engineers 19th-century Scottish businesspeople Scottish company founders