David Hicks (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

David Matthew Hicks (born 7 August 1975) is an Australian who attended

ABC Radio 11 June 2004 and fellow detainee

Hicks was captured by a "Northern Alliance warlord" near Kunduz, Afghanistan, on or about 9 December 2001 and turned over to

Hicks was captured by a "Northern Alliance warlord" near Kunduz, Afghanistan, on or about 9 December 2001 and turned over to

Australian and US critics speculated that the one-year media ban was a condition requested by the Australian government and granted as a political favour. Senator Bob Brown of the

Australian and US critics speculated that the one-year media ban was a condition requested by the Australian government and granted as a political favour. Senator Bob Brown of the

, ''AWG awards Chris Tugwell with Life Membership'', 29 August 2012 The radio adaptation was awarded the bronze medal for Best Drama Special at the New York Festival's 2006 International Radio Awards.Adelaide College of the Arts

''"SPOKE" breaks a leg!'' (1 January 2011)

"The Trials of David Hicks"

(multimedia), ''

''The President Versus David Hicks''

(2004). A documentary about the "Australian Taliban", David Hicks. The film follows the struggles of David's father. Produced by SBS TV. Directed by Curtis Levy and Bentley Dean. Written by Luke Thomas Crowe. 52 minutes.

"David Hicks: his first public address since the publication of his memoir", interview with Donna Mulhearn

(audio), Radio National goes to the 2011 Sydney Writers' Festival (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) (2011).

"Former Guantanamo detainee David Hicks speaks with the World Socialist Web Site"

By Richard Phillips (22 October 2011).

Assange plea deal has echoes of David Hicks

By

al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

's Al Farouq training camp The Al Farouq training camp, also called ''Jihad Wel al-Farouq'', was a Taliban and Al-Qaeda training camp near Kandahar, Afghanistan. Camp attendees received small-arms training, map-reading, orientation, explosives training, and other training. Na ...

in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

. Hicks traveled to Pakistan after converting to Islam to learn more about the faith, eventually leading to his time in the training camp. He alleges that he was unfamiliar with al-Qaeda and had no idea that they targeted civilians. Hicks met with Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

in 2001.

Later that year, he was captured and brought to the U.S. to be tried. He was then detained by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in Guantanamo Bay detention camp

The Guantanamo Bay detention camp ( es, Centro de detención de la bahía de Guantánamo) is a United States military prison located within Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, also referred to as Guantánamo, GTMO, and Gitmo (), on the coast of Guant ...

, where he reported undergoing torture at the hands of American soldiers, from 2002 until 2007. He was eventually convicted under the Military Commissions Act of 2006

The Military Commissions Act of 2006, also known as HR-6166, was an Act of Congress signed by President George W. Bush on October 17, 2006. The Act's stated purpose was "to authorize trial by military commission for violations of the law of ...

.

In 2012, his conviction was overturned because the law under which he was charged had not been passed at the time that his crimes were committed.

Early life

David Hicks was born inAdelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

, to Terry

Terry is a unisex given name, derived from French Thierry and Theodoric. It can also be used as a diminutive nickname for the names Teresa or Theresa (feminine) or Terence (given name), Terence or Terrier (masculine).

People

Male

* Terry Albrit ...

and Susan Hicks. His parents separated when he was ten years old, and his father later remarried. He has a half sister.

Described by his father as "a typical boy who couldn't settle down" and by his former school principal as one of "the most troublesome kids", Hicks reportedly experimented with alcohol and drugs as a teenager and was expelled from Smithfield Plains High School in 1990 at age 14. Before turning 15, Hicks was given dispensation by his father from attending school. His former partner has claimed that Hicks turned to criminal activity, including vehicle theft, allegedly in order to feed himself, although no adult criminal record was ever recorded for this.

Hicks moved between various jobs, including factory work and working at a series of outback cattle stations

Station may refer to:

Agriculture

* Station (Australian agriculture), a large Australian landholding used for livestock production

* Station (New Zealand agriculture), a large New Zealand farm used for grazing by sheep and cattle

** Cattle statio ...

in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (commonly abbreviated as NT; formally the Northern Territory of Australia) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian territory in the central and central northern regions of Australia. The Northern Territory ...

, Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

.

Marriage and family

Hicks met Jodie Sparrow in Adelaide when he was 17 years old. Sparrow already had a daughter, whom Hicks raised as his own. Hicks and Sparrow had two children together, daughter Bonnie and son Terry, before separating in 1996. After their separation, Hicks moved toJapan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

to become a horse trainer.

He married Aloysia Brooks in 2009. Hicks appeared in court in April 2017 for allegedly assaulting a subsequent partner in Craigmore, South Australia

Craigmore is a large suburb north of Adelaide, South Australia. It is in the City of Playford local government area, just east of Elizabeth and south of Gawler.

History

Craigmore is within the traditional territory of the Aboriginal Kaurna peo ...

but the case was dropped with legal costs awarded against the South Australia Police

South Australia Police (SAPOL) is the police force of the Australian state of South Australia. SAPOL is an independent statutory agency of the Government of South Australia directed by the Commissioner of Police, who reports to the Minister for ...

.

Guantanamo Bay

In 2007, Hicks consented to a plea bargain in which he pleaded guilty to charges ofproviding material support for terrorism

In United States law, providing material support for terrorism is a crime prohibited by the USA PATRIOT Act and codified in title 18 of the United States Code, section2339Aan2339B It applies primarily to groups designated as terrorists by the St ...

by the United States Guantanamo military commission

ThGuantanamo military commissionswere established by President George W. Bush – through a Military Order – on November 13, 2001, to try certain non-citizen terrorism suspects at the Guantanamo Bay prison. To date, there have been a total of e ...

under the ''Military Commissions Act of 2006

The Military Commissions Act of 2006, also known as HR-6166, was an Act of Congress signed by President George W. Bush on October 17, 2006. The Act's stated purpose was "to authorize trial by military commission for violations of the law of ...

''. Hicks received a suspended sentence and returned to Australia. The conviction was overturned by the US Court of Military Commission Review

The Military Commissions Act of 2006 mandated that rulings from the Guantanamo military commissions could be appealed to a Court of Military Commission Review, which would sit in Washington D.C.

In the event, the Review Court was not ...

in February 2015.

Hicks became one of the first people charged and subsequently convicted under the ''Military Commissions Act''. There was widespread Australian and international criticism and political controversy over Hicks' treatment, the evidence tendered against him, his trial outcome, and the newly created legal system under which he was prosecuted. In October 2012, the United States Court of Appeals ruled that the charge under which Hicks had been convicted was invalid because the law did not exist at the time of the alleged offence, and it could not be applied retroactively.

In January 2015, Hicks' lawyer announced that the US government had said that Hick's conviction was not correct and that it does not dispute his innocence.

Earlier, during 1999, Hicks converted to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

and took the name Muhammed Dawood (محمد داود). He was later reported to have been publicly denounced due to his lack of religious observance. Hicks was captured in Afghanistan in December 2001 by the Afghan Northern Alliance

The Northern Alliance, officially known as the United Islamic National Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan ( prs, جبهه متحد اسلامی ملی برای نجات افغانستان ''Jabha-yi Muttahid-i Islāmi-yi Millī barāyi Nijāt ...

and sold for a US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

5,000 bounty to the United States military. He was transported to Guantanamo Bay where he was designated an enemy combatant

Enemy combatant is a person who, either lawfully or unlawfully, engages in hostilities for the other side in an armed conflict. Usually enemy combatants are members of the armed forces of the state with which another state is at war. In the case ...

. He alleged that during his detention, he was tortured via anal examination. The United States first filed charges against Hicks in 2004 under a military commission system newly created by Presidential Order. Those proceedings failed in 2006 when the Supreme Court of the United States ruled, in ''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'', 548 U.S. 557 (2006), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay violated both the Uniform Code of Mili ...

'', that the military commission system was unconstitutional. The military commission system was re-established by an act of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

.

Revised charges were filed against Hicks in February 2007 before a new commission under the new act. The following month, in accordance with a pre-trial agreement struck with convening authority

The term convening authority is used in United States military law to refer to an individual with certain legal powers granted under either the Uniform Code of Military Justice (i.e. the regular military justice system) or the Military Commissions ...

Judge Susan J. Crawford

Susan Jean Crawford (born April 22, 1947) is an American lawyer, who was appointed the Convening Authority for the Guantanamo military commissions, on February 7, 2007.

United States Secretary of Defense, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates appoin ...

, Hicks entered an Alford plea

In United States law, an Alford plea, also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia, an Alford guilty plea, and the Alford doctrine, is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and ...

to a single newly codified charge of providing material support for terrorism. Hicks's legal team attributed his acceptance of the plea bargain

A plea bargain (also plea agreement or plea deal) is an agreement in criminal law proceedings, whereby the prosecutor provides a concession to the defendant in exchange for a plea of guilt or '' nolo contendere.'' This may mean that the defendan ...

to his "desperation for release from Guantanamo" and duress under "instances of severe beatings, sleep deprivation and other conditions of detention that contravene international human rights norms."

Return to Australia

In April 2007, Hicks was returned to Australia to serve the remaining nine months of a suspended seven-year sentence. During this period, he was precluded from all media contact. There was criticism that the government delayed his release until after the2007 Australian election

The 2007 Australian federal election was held in Australia on 24 November 2007. All 150 seats in the House of Representatives and 40 of the seats in the 76-member Senate were up for election. The election featured a 39-day campaign, with 13.6 ...

. Colonel Morris Davis, the former Pentagon

In geometry, a pentagon (from the Greek πέντε ''pente'' meaning ''five'' and γωνία ''gonia'' meaning ''angle'') is any five-sided polygon or 5-gon. The sum of the internal angles in a simple pentagon is 540°.

A pentagon may be simpl ...

chief prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

, later confessed political interference in the case by the Bush administration in the United States and the Howard

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

government in Australia. He said that Hicks should not have been prosecuted.

Hicks served his term in Adelaide's Yatala Labour Prison

Yatala Labour Prison is a high-security men's prison located in the north-eastern part of the northern Adelaide suburb Northfield, South Australia. It was built in 1854 to enable prisoners to work at Dry Creek, quarrying rock for roads and con ...

and was released under a control order A control order is an order made by the Home Secretary of the United Kingdom to restrict an individual's liberty for the purpose of "protecting members of the public from a risk of terrorism". Its definition and power were provided by Parliament in ...

on 29 December 2007. The control order expired in December 2008. Hicks still lives in Adelaide and has written an autobiography.

Religious and militant activities

Hicks converted toIslam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, and began studying Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

at a mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

in Gilles Plains

Gilles Plains is a suburb of the greater Adelaide, South Australia area, approximately 10km north-east of the Adelaide central business district.

History

It is named after the first Colonial Treasurer Osmond Gilles who owned a sheep station adj ...

, a suburb north of Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. The president of the Islamic Society of South Australia

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, Wali Hanifi, described Hicks as having "some interest in military things", and that "after personal experience and research, oundthat Islam was the answer".

In 2010, Hicks explained his motivation to convert to Islam:

My motivation was not a religious search for spirituality; it was more a search for somewhere to belong and to be with people who shared my interest in world affairs. In my youth I was impulsive. Unfortunately, many of my decisions of that time are a reflection of that trait.He renounced his faith during the earlier years of his detention at Guantánamo. In June 2006,

Moazzam Begg

Moazzam Begg ( ur, ; born 5 July 1968 in Sparkhill, Birmingham) is a British Pakistani who was held in extrajudicial detention by the US government in the Bagram Theater Internment Facility and the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp, in Cuba, for ...

, a British man who had also been held at Guantanamo Bay but was released in 2005, claimed in his book, ''Enemy Combatant: A British Muslim's Journey to Guantanamo and Back'', that Hicks had abandoned his Islamic beliefs, and had been denounced by a fellow inmate, Uthman al-Harbi, for his lack of observance. This has also been confirmed by his military lawyer, Major Michael Mori

Michael Dante Mori, also known as Dan Mori (born 1965), is an American lawyer who attained the rank of Lieutenant colonel (United States), lieutenant colonel in the United States Marine Corps. Mori was the military lawyer for Australian Guantanamo ...

, who declined to say why Hicks was no longer a Muslim, saying it was a personal issue.

Kosovo Liberation Army

Around May 1999, Hicks travelled to Albania in order to join theKosovo Liberation Army

The Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA; , UÇK) was an ethnic Albanian separatist militia that sought the separation of Kosovo, the vast majority of which is inhabited by Albanians, from the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) and Serbia during the ...

. The US military alleged that he undertook basic training and hostile action before returning to Australia and converting to Islam. The KLA did not accept Islamic fundamentalism, and many of its fighters and fundraisers were Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. In June 1999, the Kosovo War

The Kosovo War was an armed conflict in Kosovo that started 28 February 1998 and lasted until 11 June 1999. It was fought by the forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (i.e. Serbia and Montenegro), which controlled Kosovo before the war ...

ended and the KLA disbanded as part of UNSCR 1244. Hicks described his time with the KLA as a life-changing experience and on his return to Australia, converted to Islam and began studying at a mosque in Gilles Plains

Gilles Plains is a suburb of the greater Adelaide, South Australia area, approximately 10km north-east of the Adelaide central business district.

History

It is named after the first Colonial Treasurer Osmond Gilles who owned a sheep station adj ...

in Adelaide.

Lashkar-e-Taiba

On 11 November 1999, Hicks travelled toPakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

to study Islam and allegedly began training with Lashkar-e-Taiba

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT; ur, ; literally ''Army of the Good'', translated as ''Army of the Righteous'', or ''Army of the Pure'' and alternatively spelled as ''Lashkar-e-Tayyiba'', ''Lashkar-e-Toiba'', ''Lashkar-i-Taiba'', ''Lashkar-i-Tayyeba'') ...

(L-e-T) in early 2000. In the US Military Commission charges presented in 2004, Hicks is accused of training at the Mosqua Aqsa camp in Pakistan, after which he "travelled to a border region between Pakistan-controlled Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

and Indian-controlled Kashmir, where he engaged in hostile action against Indian forces.".

In a March 2000 letter to his family, Hicks wrote:

don't ask what's happened, I can't be bothered explaining the outcome of these strange events has put me in Pakistan-Kashmir in a training camp. Three months training. After which it is my decision whether to cross the line of control into Indian occupied Kashmir.In another letter on 10 August 2000, Hicks wrote from Kashmir claiming to have been a guest of Pakistan's army for two weeks at the front in the "controlled war" with

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

:

I got to fire hundreds of bullets. Most Muslim countries impose hanging for civilians arming themselves for conflict. There are not many countries in the world where a tourist, according to his visa, can go to stay with the army and shoot across the border at its enemy, legally.During this period, Hicks kept a notebook to document his training in weapon use, explosives, and military tactics, in which he wrote that guerrilla warfare involved "sacrifice for Allah". He took extensive notes on, and made sketches of, various weaponry mechanisms and attack strategies (including

Heckler & Koch

Heckler & Koch GmbH (HK; ) is a German defense manufacturing company that manufactures handguns, rifles, submachine guns, and grenade launchers. The company is located in Oberndorf am Neckar in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, and also ...

submachine guns, the M16

The M16 rifle (officially designated Rifle, Caliber 5.56 mm, M16) is a family of military rifles adapted from the ArmaLite AR-15 rifle for the United States military. The original M16 rifle was a 5.56×45mm automatic rifle with a 20-roun ...

assault rifle, RPG-7

The RPG-7 (russian: link=no, РПГ-7, Ручной Противотанковый Гранатомёт, Ruchnoy Protivotankoviy Granatomyot) is a portable, reusable, unguided, shoulder-launched, anti-tank, rocket-propelled grenade launcher. ...

grenade launcher, anti-tank rockets, and VIP security infiltration). Letters to his family detailed his training:

I learnt about weapons such as ballistic missiles, surface to surface and shoulder fired missiles, anti aircraft and anti-tank rockets, rapid fire heavy and light machine guns, pistols,In January 2001, Hicks was provided with funding and an introductory letter from Lashkar-e-Taiba. He travelled to Afghanistan to attend training. According to Hicks' autobiography '' Guantanamo: My Journey'', he was unfamiliar with the name Al-Qaeda until after his detainment in Guantanamo Bay.AK-47 The AK-47, officially known as the ''Avtomat Kalashnikova'' (; also known as the Kalashnikov or just AK), is a gas operated, gas-operated assault rifle that is chambered for the 7.62×39mm cartridge. Developed in the Soviet Union by Russian s ...s, mines and explosives. After three months everybody leaves capable and war-ready being able to use all of these weapons capably and responsibly. I am now very well trained for jihad in weapons some serious like anti-aircraft missiles.

Afghanistan

Upon arrival in Afghanistan, Hicks allegedly went to an al-Qaeda guest house where he metIbn al-Shaykh al-Libi

Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi (; ALFB transliteration: ''Ḁbnʋ ălŞɑỉƈ alLibi''; born Ali Mohamed Abdul Aziz al-Fakheri; 1963 – May 10, 2009) was a Libyan national captured in Afghanistan in November 2001 after the fall of the Taliban; he was i ...

, a high-ranking al Qaeda member. He turned over his passport and told them that he would use the alias "Muhammad Dawood" (to protect himself from attack).

Hicks allegedly "attended a number of al-Qaeda training courses at various camps around Afghanistan, learning guerrilla warfare, weapons training, including landmines, kidnapping techniques and assassination methods." He also allegedly participated "in an advanced course on surveillance, in which he conducted surveillance of the abandoned buildings that had formerly been the US and British embassies in Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

, Afghanistan." Hicks was sent to learn guerrilla techniques for the Pakistani L-e-T for use in disputed Kashmir.

Hicks denies any involvement with al-Qaeda. He also denies any knowledge of links between the camp and al-Qaeda. According to Hicks, he did not know of the existence of al-Qaeda until he was taken to Cuba and was interrogated by US military personnel.

On one occasion when al-Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

visited an Afghan camp, the US Defense Department alleges Hicks questioned bin Laden about the lack of English in training material and subsequently "began to translate the training camp materials from Arabic to English". Hicks denies this and denies having had the necessary language proficiency, a claim supported by Major Michael Mori

Michael Dante Mori, also known as Dan Mori (born 1965), is an American lawyer who attained the rank of Lieutenant colonel (United States), lieutenant colonel in the United States Marine Corps. Mori was the military lawyer for Australian Guantanamo ...

David Hicks chargedABC Radio 11 June 2004 and fellow detainee

Moazzam Begg

Moazzam Begg ( ur, ; born 5 July 1968 in Sparkhill, Birmingham) is a British Pakistani who was held in extrajudicial detention by the US government in the Bagram Theater Internment Facility and the Guantanamo Bay detainment camp, in Cuba, for ...

. The latter said that Hicks could not speak enough Arabic to be understood. Hicks wrote home that he had met Osama bin Laden 20 times. He later, however, told investigators he had exaggerated, that he had seen bin Laden about eight times and spoken to him only once.

There are a lot of Muslims who want to meet Osama Bin Laden but after being a Muslim for 16 months I get to meet him.Prosecutors also allege Hicks was interviewed by

Mohammed Atef

Mohammed Atef ( ar, محمد عاطف, ; born Sobhi Mohammed Abu Sitta Al-Gohary, also known as Abu Hafs al-Masri) was the military chief of al-Qaeda, and was considered one of Osama bin Laden's two deputies, the other being Ayman Al Zawahiri, ...

, an al-Qaeda military commander, about his background and "the travel habits of Australians". In a memoir that was later repudiated by its author, the Guantanamo detainee Feroz Abbasi

Feroz Abbasi is one of nine British men who were held in extrajudicial detention in the United States Guantanamo Bay detainment camps, in Cuba. He was repatriated in 2005 and released by the British government the next day. He was released from det ...

claimed Hicks was "Al-Qaedah's 24 aratGolden Boy" and "obviously the favourite recruit" of their al-Qaeda trainers during exercises at the al-Farouq camp The Al Farouq training camp, also called ''Jihad Wel al-Farouq'', was a Taliban and Al-Qaeda training camp near Kandahar, Afghanistan. Camp attendees received small-arms training, map-reading, orientation, explosives training, and other training. Na ...

near Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a List of cities in Afghanistan, city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population ...

. The memoir made a number of claims, including that Hicks was teamed in the training camp with Filipino

Filipino may refer to:

* Something from or related to the Philippines

** Filipino language, standardized variety of 'Tagalog', the national language and one of the official languages of the Philippines.

** Filipinos, people who are citizens of th ...

recruits from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front

The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF; ar, ''Jabhat Taḥrīr Moro al-ʾIslāmiyyah'') is a group based in Mindanao seeking an autonomous region of the Moro people from the central government. The group has a presence in the Bangsamoro r ...

and that, during internment in Camp X-Ray, Hicks allegedly described his desire to "go back to Australia and rob and kill Jews ... crash a plane into a building" and to "go out with that last big adrenaline rush."

September 2001

On 9 September 2001, Hicks travelled from Afghanistan to Pakistan to visit a friend. AUS Department of Defense

The United States Department of Defense (DoD, USDOD or DOD) is an executive branch department of the federal government charged with coordinating and supervising all agencies and functions of the government directly related to national secu ...

statement claimed that "viewing TV news coverage in Pakistan of the 11 September 2001 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commerc ...

against the United States" led Hicks to return to Afghanistan to "rejoin his al-Qaeda associates to fight against U.S., British, Canadian, Australian, Afghan, and other coalition forces." Hicks denies this claim in his book. Although the L-e-T offered to provide documentation to allow him to return to Australia, Hicks feared arrest for using false documents. Hicks returned in order to get his passport and birth certificate back so he could travel home to Adelaide.

Hicks arrived in the southern Afghan city of Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a List of cities in Afghanistan, city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population ...

where he reported to Saif al Adel, who was assigning individuals to locations, and "armed himself with an AK-47

The AK-47, officially known as the ''Avtomat Kalashnikova'' (; also known as the Kalashnikov or just AK), is a gas operated, gas-operated assault rifle that is chambered for the 7.62×39mm cartridge. Developed in the Soviet Union by Russian s ...

automatic rifle, ammunition, and grenades to fight against coalition forces." Hicks was given a choice of three locations and chose to join an alleged group of al-Qaeda fighters defending the Kandahar airport. After Coalition bombing commenced in October 2001, Hicks began guarding a Taliban tank position outside the airport. After guarding the tank for a week, Hicks, with an L-e-T acquaintance, travelled closer to the battle front in Kunduz where he joined others, including John Walker Lindh.

Colonel Morris Davis, chief prosecutor for the US office of Military Commissions, said, "He eventually left Afghanistan and it's my understanding was heading back to Australia when 9/11 happened. When he heard about 9/11, he said it was a good thing (and) he went back to the battlefield, back to Afghanistan, and reported in to the senior leadership of al-Qaeda and basically said, 'I'm David Hicks and I'm reporting for duty. Davis also compared Hicks' alleged actions to that of those who carried out terrorist attacks such as the Bali, London and Madrid bombings, and the Beslan school siege. Terry Hicks, said that his son seemed at first unaware, then sceptical, of the 11 September attacks when they spoke on a mobile phone in early November 2001. He also noted David Hicks commented about "going off to Kabul to defend it against the Northern Alliance

The Northern Alliance, officially known as the United Islamic National Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan ( prs, جبهه متحد اسلامی ملی برای نجات افغانستان ''Jabha-yi Muttahid-i Islāmi-yi Millī barāyi Nijāt ...

."

In October and November 2001, Hicks wrote multiple letters to his mother in Australia. He asked that replies were to be directed to Abu Muslim Austraili, a pseudonym he used to circumvent non-Muslim spies he believed intercepted correspondence. In these letters he detailed the validity of jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

and his own prospect of martyrdom

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external ...

.

As a Muslim young and fit my responsibility is to protect my brothers from aggressive non-believers and not let them destroy it. Islam will rule again but for now we must have patience we are asked to sacrifice our lives for Allahs cause why not? There are many privileges in heaven. It is not just war, it is jihad. One reward I get in being martyred I get to take ten members of my family to heaven who were destined for hell, but first I also must be martyred. We are all going to die one day so why not be martyred?David Hicks wrote a number of anti Semitic letters during his time in Afghanistan which were published in ''

The Australian

''The Australian'', with its Saturday edition, ''The Weekend Australian'', is a broadsheet newspaper published by News Corp Australia since 14 July 1964.Bruns, Axel. "3.1. The active audience: Transforming journalism from gatekeeping to gatew ...

'' with statements such as "The Jews have complete financial and media control many of them are in the Australian government" and "The western society is controlled by the Jews".

In November 2005, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) is the national broadcaster of Australia. It is principally funded by direct grants from the Australian Government and is administered by a government-appointed board. The ABC is a publicly-own ...

's ''Four Corners

The Four Corners is a region of the Southwestern United States consisting of the southwestern corner of Colorado, southeastern corner of Utah, northeastern corner of Arizona, and northwestern corner of New Mexico. The Four Corners area ...

'' TV program broadcast for the first time a transcript of an interview with Hicks, conducted by the Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) is the national and principal federal law enforcement agency of the Australian Government with the unique role of investigating crime and protecting the national security of the Commonwealth of Australia. Th ...

(AFP) in 2002, and other material, including a report that Hicks had signed a statement written by American military investigators stating that he had trained with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, learning guerrilla tactics and urban warfare. The program also reported that Hicks had met Osama bin Laden and that he claimed to have disapproved of the 11 September attacks but to have been unable to leave Afghanistan. He denied engaging in any actual fighting against US or allied forces and states in his autobiography that he was made to sign the statement under extreme duress.

Capture and detention

Hicks was captured by a "Northern Alliance warlord" near Kunduz, Afghanistan, on or about 9 December 2001 and turned over to

Hicks was captured by a "Northern Alliance warlord" near Kunduz, Afghanistan, on or about 9 December 2001 and turned over to US Special Forces

The United States Army Special Forces (SF), colloquially known as the "Green Berets" due to their distinctive service headgear, are a special operations force of the United States Army.

The Green Berets are geared towards nine doctrinal mis ...

for US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

5000 on 17 December 2001. Hicks's father Terry, when interviewed, said "David was captured by the Northern Alliance unarmed in the back of a truck or a van. So he wasn't on the battlefield at all."

In 2002, Hicks's father sought to have him brought to Australia for trial. In 2003, the Australian government requested that Hicks be brought to trial without further delay, extending Hicks consular support and legal aid under the Special Circumstances Overseas Scheme.

Torture allegations

In an affidavit, dated 5 August 2004 and released on 10 December 2004, Hicks alleged mistreatment by US forces, included being: * beaten while blindfolded and handcuffed * forced to take unidentified medication * sedated by injection without consent * struck while under sedation * regularly forced to run in leg shackles causing ankle injury *deprived of sleep

Sleep deprivation, also known as sleep insufficiency or sleeplessness, is the condition of not having adequate duration and/or quality of sleep to support decent alertness, performance, and health. It can be either chronic or acute and may vary ...

"as a matter of policy"

* sexually assaulted

* witness to use of attack dogs to brutalise and injure detainees.

He also said he met with US military investigators conducting a probe into detainee abuse in Afghanistan and had told the International Red Cross on earlier occasions that he had been mistreated. Hicks told his family in a 2004 visit to Guantanamo Bay that he had been anally assaulted during interrogation by the US in Afghanistan while he was hooded and restrained. Hicks' father claimed; "He said he was anally penetrated a number of times, they put a bag over his head, he wasn't expecting it and didn't know what it was. It was quite brutal." In a ''Four Corners'' interview, Terry Hicks discussed these "allegations of physical and sexual abuse of his son by American soldiers".

According to conversations with his father, Hicks said he had been abused by both Northern Alliance and US soldiers. In response, the Australian government announced its acceptance of US assurances that David Hicks had been treated in accordance with international law.

In March 2006, camp authorities moved all ten of the Guantanamo detainees who faced charges into solitary confinement. This was described as a routine measure because of the impending attendance of the detainees at their respective tribunals. Hicks remained in solitary confinement, which was reported to have "deteriorated his condition," for seven weeks after the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

confirmed a ruling that the military commissions were unconstitutional.

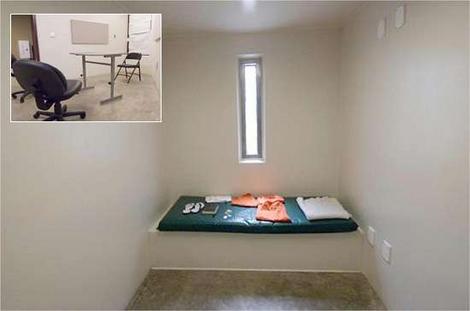

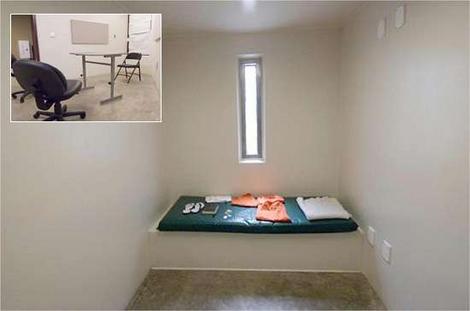

Hicks was a well-behaved detainee, but was in solitary confinement for 23 hours a day. The window in his cell was internal, facing onto a corridor. Hicks claimed to have declined a visit from Australian Consular officials because he had been punished for speaking candidly with consular officials about the conditions of his detention on previous visits. Hicks was talking about suicidal impulses during his periods in isolation at Camp Echo. "He often talked about wanting to smash his head ... against the metal of his cage and just end it all", Mozzam Begg said.

Indictment

Initial charges

Hicks was charged by a US military commission on 26 August 2004. In Guantanamo, Hicks had signed a statement written by American military investigators which read, in part, "I believe that al-Qaeda camps provided a great opportunity for Muslims like myself from all over the world to train for military operations and Jihad. I knew after six months that I was receiving training from al-Qaeda, who had declared war on numerous countries and peoples." The indictment later prepared by US military prosecutors for his commission trial alleged that, prior to his capture in 2001, Hicks had trained and conspired in various ways and was guilty of "aiding the enemy" while an " unprivileged belligerent" but did not allege any specific acts of violence. The indictment made the following allegations: * In November 1999, Hicks travelled toPakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, where he joined the paramilitary Islamist group, Lashkar-e-Toiba

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT; ur, ; literally ''Army of the Good'', translated as ''Army of the Righteous'', or ''Army of the Pure'' and alternatively spelled as ''Lashkar-e-Tayyiba'', ''Lashkar-e-Toiba'', ''Lashkar-i-Taiba'', ''Lashkar-i-Tayyeba'') ...

(Army of the Pure).

* Hicks trained for two months at a Lashkar-e-Toiba camp in Pakistan, where he received weapons training and that, during 2000, he served with a Lashkar-e-Toiba group near the Pakistan administered Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompass ...

.

* In January 2001, Hicks travelled to Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, then under the control of the Taliban

The Taliban (; ps, طالبان, ṭālibān, lit=students or 'seekers'), which also refers to itself by its state (polity), state name, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a Deobandi Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic fundamentalist, m ...

regime, where he presented a letter of introduction from Lashkar-e-Toiba to Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi

Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi (; ALFB transliteration: ''Ḁbnʋ ălŞɑỉƈ alLibi''; born Ali Mohamed Abdul Aziz al-Fakheri; 1963 – May 10, 2009) was a Libyan national captured in Afghanistan in November 2001 after the fall of the Taliban; he was i ...

, a senior al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

member, and was given the alias "Mohammed Dawood".

* Hicks was sent to al-Qaeda's al-Farouq training camp outside Kandahar

Kandahar (; Kandahār, , Qandahār) is a List of cities in Afghanistan, city in Afghanistan, located in the south of the country on the Arghandab River, at an elevation of . It is Afghanistan's second largest city after Kabul, with a population ...

, where he trained for eight weeks, receiving further weapons training as well as training with land mines and explosives.

* Hicks did a further seven-week course at al-Farouq, during which he studied marksmanship, ambush, camouflage and intelligence techniques.

* At Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Mohammed bin Awad bin Laden (10 March 1957 – 2 May 2011) was a Saudi-born extremist militant who founded al-Qaeda and served as its leader from 1988 until Killing of Osama bin Laden, his death in 2011. Ideologically a Pan-Islamism ...

's request, Hicks translated some al-Qaeda training materials from Arabic into English.

* In June 2001, on the instructions of Mohammed Atef

Mohammed Atef ( ar, محمد عاطف, ; born Sobhi Mohammed Abu Sitta Al-Gohary, also known as Abu Hafs al-Masri) was the military chief of al-Qaeda, and was considered one of Osama bin Laden's two deputies, the other being Ayman Al Zawahiri, ...

, an al-Qaeda military commander, Hicks went to another training camp at Tarnak Farm

Tarnak Farms refers to a former Afghan training camp near Kandahar, which served as a base to Osama bin Laden and his followers from 1998 to 2001.

9-11 hijackers believed to have trained at Tarnak Farms

Home to bin Laden

In 1998, bin Laden m ...

, where he studied "urban tactics", including the use of assault and sniper rifles, rappelling, kidnapping and assassination techniques.

* In August 2001, Hicks went to Kabul

Kabul (; ps, , ; , ) is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province; it is administratively divided into 22 municipal districts. Acco ...

, where he studied information collection and intelligence, as well as Islamic theology including the doctrines of ''jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

'' and martyrdom as understood through al-Qaeda's fundamentalist interpretation of Islam.

* In September 2001, Hicks travelled to Pakistan and was there at the time of the 11 September attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated Suicide attack, suicide List of terrorist incidents, terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, ...

on the United States, which he saw on television.

* Hicks returned to Afghanistan in anticipation of the attack by the United States and its allies on the Taliban regime, which was sheltering Osama bin Laden.

* On returning to Kabul, Hicks was assigned by Mohammed Atef to the defence of Kandahar and that he joined a group of mixed al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters at Kandahar airport. At the end of October, however, Hicks and his party travelled north to join in the fighting against the forces of the US and its allies.

* After arriving in Konduz

, native_name_lang = prs

, other_name =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline = Kunduz River valley.jpg

, imagesize = 300

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, image_ ...

on 9 November 2001, he joined a group which included John Walker Lindh (the "American Taliban"). This group was engaged in combat against Coalition forces and, during the fighting, he was captured by Coalition forces.

On 29 June 2006, the US Supreme Court ruled in ''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'', 548 U.S. 557 (2006), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay violated both the Uniform Code of Mili ...

'' that the military commissions were illegal under United States law and the Geneva Conventions. The commission trying Hicks was abolished and the charges against him voided.

In an interview with ''The Age

''The Age'' is a daily newspaper in Melbourne, Australia, that has been published since 1854. Owned and published by Nine Entertainment, ''The Age'' primarily serves Victoria (Australia), Victoria, but copies also sell in Tasmania, the Austral ...

'' newspaper in January 2007, Col. Morris Davis, the chief prosecutor in the Guantanamo military commissions, also alleged that Hicks had been issued with weapons to fight US troops, and had conducted surveillance against US and international embassies. Davis stated he would be charged for these offences, and predicted the charging would take place before the end of January. He alleged that Hicks "knew and associated with a number of al-Qaeda senior leadership" and that "he conducted surveillance on the US embassy and other embassies". He went on to compare Hicks to the Bali bombers, expressing concern that Australians were misjudging the military commission system due to PR "smoke" from Hicks's lawyer.

James Yee

James Joseph Yee ( or 余优素福, also known by the Arabic name Yusuf Yee) (born c. 1968) is an American former United States Army chaplain with the rank of captain. He worked as a Muslim chaplain at Guantanamo Bay detention camp and was subje ...

, an Islamic US Army chaplain who regularly counselled Hicks while detained at Guantanamo Bay, gave a statement shortly after Hicks was freed in December 2007. He said that he did not feel Hicks was a threat to Australia, and that "Any American soldier who has been through basic training has had 50 times more training than this guy."

Trial delays

Defence team

The US Army appointedUnited States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

Major Michael Mori

Michael Dante Mori, also known as Dan Mori (born 1965), is an American lawyer who attained the rank of Lieutenant colonel (United States), lieutenant colonel in the United States Marine Corps. Mori was the military lawyer for Australian Guantanamo ...

as defence counsel to Hicks. Hicks's civilian defence was being funded by Dick Smith, an Australian entrepreneur. Smith has stated that he was funding the defence "to get him a fair trial".

Delays in legal proceedings

In November 2004, Hicks's trial was delayed when a US Federal Court ruled that the military commissions in question were unconstitutional. In February 2005, the Hicks's family lawyer, Stephen Kenny, who had been representing Hicks in Australia without compensation since 2002, was dismissed from the defence team and Vietnam veteran and army reservist David McLeod replaced him. Hicks's trial was next set for 10 January 2005 but there were numerous postponements and further legal wrangling over the years that followed. In mid-February 2005, Jumana Musa,Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

's legal observer at Guantanamo Bay, visited Australia to speak to the attorney-general, Philip Ruddock, (a member of Amnesty International) about the military commissions. Musa stated that Australia was "the only country that seems to have come out and said that the idea of trying somebody, their own citizen, before this process might be OK, and I think that should be a concern to anybody."

In July 2005, a US appeals court accepted the prosecution claim that because "the President of the United States issued a memorandum in which he determined that none of the provisions of the Geneva Conventions apply to our conflict with al-Qaeda in Afghanistan or elsewhere throughout the world because, among other reasons, al Qaeda is not a high contracting party to Geneva", that Hicks, among others, could be tried by a military tribunal. In July 2005, the US appeals court ruled that the trial of "Unlawful Combatants" did not come under the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

, and that they could be tried by a military tribunal.

In early August 2005, leaked emails from former US prosecutors criticised the legal process, accusing it of being "a half-hearted and disorganised effort by a skeleton group of relatively inexperienced attorneys to prosecute fairly low-level accused in a process that appears to be rigged" and "writing a motion saying that the process will be full and fair when you don't really believe it is kind of hard, particularly when you want to call yourself an officer and lawyer". Ruddock responded by saying that the emails, written in March 2004, "must be seen as historic rather than current." In October 2005, the US government announced that if Hicks was convicted, his pre-trial detention would not count as time served against his sentence.

On 15 November 2005, District

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions o ...

Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly

Colleen Constance Kollar-Kotelly (born April 17, 1943) is an American lawyer serving as a Senior United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia and was previously presiding judge of the Foreign Intell ...

stayed the proceeding against Hicks until the US Supreme Court had ruled on Hamdan's appeal over their constitutionality.

2006 was also fraught with delays. On 29 June 2006, in the case ''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld

''Hamdan v. Rumsfeld'', 548 U.S. 557 (2006), is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that military commissions set up by the Bush administration to try detainees at Guantanamo Bay violated both the Uniform Code of Mili ...

'', the US Supreme Court ruled that the military tribunals were illegal under United States law and the Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

. On 7 July 2006, a memo was issued from The Pentagon directing that all military detainees are entitled to humane treatment and to certain basic legal standards, as required by Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. On 15 August 2006, Attorney-General Philip Ruddock announced that he would seek to return Hicks to Australia if the United States did not proceed quickly to lay substantive new charges. As a result of the Supreme Court decision, the United States Congress passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006 to provide an alternative method for trying detainees held at Guantanamo Bay. The Act was signed into law by President Bush on 17 October 2006.

On 6 December 2006, Hicks's legal team lodged documents with the Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia is an Australian superior court of record which has jurisdiction to deal with most civil disputes governed by federal law (with the exception of family law matters), along with some summary (less serious) and indic ...

, arguing that the Australian government had breached its protective duty to Hicks as an Australian citizen in custody overseas, and failed to request that Hicks's incarceration by the US comply with the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedo ...

and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal De ...

.

On 9 March 2007, his lawyer said that David Hicks was expected to bring a case seeking to force the Australian Federal Government to ask the US government to free him. On 26 March 2007, the television journalist Leigh Sales suggested that Hicks was attempting to avoid trial by military commission, commenting "The Hicks defence strategy relies on delaying the process for so long that the Australian Government will be forced to ask for the prisoner's return."

As years passed, the legitimacy, integrity and fairness of trying Hicks before a US military commission was increasingly questioned.

British citizenship bid

In September 2005, it was realised that Hicks may be eligible for British citizenship through his mother, as a consequence of theNationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002

The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (c. 41) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It received royal assent on 7 November 2002.

This Act created a number of changes to the law including:

British Nationals with no othe ...

. Hicks's British heritage was revealed during a casual conversation with his lawyer, about the 2005 Ashes cricket series. The British government had previously negotiated the release of the nine British nationals incarcerated at Guantanamo Bay, so it was considered possible that these releases could be extended to Hicks if his application was successful.

Hicks applied for citizenship, but there were six months of delays. In November 2005, the British Home Office rejected Hicks's application for British citizenship on character grounds, but his lawyers appealed against the decision. On 13 December 2005, Lord Justice Lawrence Collins of the High Court ruled that then-Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

Charles Clarke had "no power in law" to deprive Mr Hicks of British citizenship "and so he must be registered". The Home Office announced it would take the matter to the Court of Appeal

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much of t ...

, but Justice Collins denied them a stay of judgement, meaning that the British government must proceed with the application.

On 17 March 2006 the Home Office alleged during its appeal case that Hicks had admitted in 2003 to the Security Service (British intelligence agency MI5) that he had undergone extensive terrorist training in Afghanistan. On 12 April 2006 the Court of Appeal upheld the High Court's decision that Hicks was entitled to British citizenship. The Home Office declared it would appeal the matter again, its last option being to submit an appeal to Britain's highest court, the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, no later than 25 April.

On 5 May, however, the Court of Appeal declared that no further appeals would be allowed, and that the Home Office must grant Hicks British citizenship. Hicks's legal team claimed in the High Court on 14 June 2006 that the process of Mr Hicks's registration as a British citizen had been delayed and obstructed by the United States, which had not allowed British consular access to Hicks in order to conduct the oath of allegiance to the Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. His military lawyer has the authority to administer oaths and offered to conduct the oath if the American government permitted it.

On 27 June, with Hicks's British citizenship confirmed, the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a Departments of the Government of the United Kingdom, department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ministries of fore ...

announced that it would not seek to lobby for his release as it had with the other British detainees. The reason given was that Hicks was an Australian citizen when he was captured and detained and that he had received Australian consular assistance. On 5 July 2006 Hicks was registered as a British citizen, albeit only for a few hours — Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, otherwise known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The home secretary leads the Home Office, and is responsible for all national ...

John Reid intervened to revoke Hicks's new citizenship almost as soon as it had been granted, citing section 56 of the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act 2006 allowing the Home Secretary to "deprive a person of a citizenship status if the Secretary of State is satisfied that deprivation is conducive to the public good". Hicks's legal team called the decision an "abuse of power

Abuse is the improper usage or treatment of a thing, often to unfairly or improperly gain benefit. Abuse can come in many forms, such as: physical or verbal maltreatment, injury, assault, violation, rape, unjust practices, crimes, or other t ...

", and announced they would lodge an appeal with the UK Special Immigration Appeals Commission and the High Court.

Seizure of legal papers

Following the death of three detainees, camp authorities seized prisoners' papers. Described as a security measure, it was claimed that instructions for tying a hangman's noose had been found written on stationery issued to the lawyers who met with detainees to discuss theirhabeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

requests. The Department of Justice acknowledged in court that "privileged attorney-client communications" had been seized. Hicks's lawyer questioned whether Hicks could have been part of a suicide plot, since he had spent the preceding four months in solitary confinement in a different part of the camp, and expressed concern that attorney-client confidentiality, "the last legal right that was being respected", had been violated.

New charges

On 3 February 2007, the US military commission announced that it had prepared new charges against David Hicks. The drafted charges were "attempted murder" and "providing material support for terrorism", under theMilitary Commissions Act of 2006

The Military Commissions Act of 2006, also known as HR-6166, was an Act of Congress signed by President George W. Bush on October 17, 2006. The Act's stated purpose was "to authorize trial by military commission for violations of the law of ...

. Each offence carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment. The prosecutors said they would argue for a jail term of 20 years, with an absolute minimum of 15 years to be served.

However the sentence, which was not required to take into account time already served, was ultimately up to a panel of US military officers. The Convening Authority assessed whether there was enough evidence for charges to be laid and Hicks tried. The charge of providing material support for terrorism was based on retrospectively applying the law passed in 2006.

On 16 February 2007, a nine-page charge sheet detailing the new charges was officially released by the US Defense Department.

The charge sheets alleged that:

* Around August 2001 Hicks conducted surveillance on the American and British embassies in Kabul.

* Using the name Abu Muslim Austraili he attended al-Qaeda training camps.

* Around April 2001 Hicks returned to al Farouq and trained "in al-Qa'ida's guerilla warfare and mountain tactics training course". The course included "marksmanship; small team tactics; ambush; camouflage; rendezvous techniques; and techniques to pass intelligence to al-Qa'ida operatives".

* While at the al Farouq camp, al-Qa'ida leader Osama bin Laden visited the camp on several occasions and "during one visit Hicks expressed to bin Laden his concern over the lack of English al-Qa'ida training material".

* On or about 12 September 2001 he left Pakistan after watching TV footage of the 11 September terrorist attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated Suicide attack, suicide List of terrorist incidents, terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, ...

to return to Afghanistan "and, again joined with al-Qa'ida".

* On his return to Afghanistan Hicks was issued an AK-47 automatic rifle and armed himself with 300 rounds of ammunition and 3 grenades to use in fighting the United States, Northern Alliance and other coalition forces.

* On or about 9 November 2001 Hicks spent about two hours on the front line at Konduz "before it collapsed and he was forced to flee".

* Around December 2001, Northern Alliance forces captured Hicks in Baghlan, Afghanistan.

On 1 March 2007, David Hicks was formally charged with material support for terrorism, and referred to trial by the special military commission. The second charge of attempted murder was dismissed by Judge Susan Crawford, who concluded there was "no probable cause" to justify the charge.

In March 2007, the prospect of further delay loomed when Mori was allegedly threatened with court martial for using contemptuous language toward the US executive, a US military discipline offence, by the chief US military prosecutor, Colonel Morris Davis, but no charges were filed against Mori.

Leaders and legal commentators in both countries criticised the prosecution as the application of ex post facto law and deemed the 5-year process to be a violation of Hicks's basic rights. The United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

countered that the charges relating to Hicks were not retrospective but that the Military Commissions Act had codified offences that had been traditionally tried by military commissions and did not establish any new crimes.

Hick's defence lawyer and many international judiciary members claimed that it would have been impossible for a conviction to be found against Hicks. In her book on Hicks, Australian journalist Leigh Sales examines more than five years of reporting and dozens of interviews with insiders, and looks at the intricacies of Hicks's case from his capture in Afghanistan to life in Guantanamo Bay, including behind-the-scene establishment and workings of the military commissions.

The India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n government launched an investigation into the attacks by Hicks on their armed forces in Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, during 2000.

Pre-trial agreement and sentence

On 26 March 2007, following negotiations with Hicks's defence lawyers, the convening authority Judge Susan Crawford directly approved the terms of a pre-trial agreement. The agreement stipulated that Hicks enter anAlford plea

In United States law, an Alford plea, also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia, an Alford guilty plea, and the Alford doctrine, is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and ...

to a single charge of providing material support for terrorism in return for a guarantee of a much shorter sentence than had been previously sought by the prosecution. The agreement also stipulated that the five years already spent by Hicks at Guantanamo Bay could not be subtracted from any sentence handed down, that Hicks must not speak to the media for one year nor take legal action against the United States, and that Hicks withdraw allegations that the US military abused him. Accordingly, in the first ever conviction by the Guantanamo military tribunal and the first conviction in a US war crimes trial since World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, on 31 March, the tribunal handed down a seven-year jail sentence for the charge, suspending all but nine months.

The length of the sentence caused an "outcry" in the United States and against Defense Department lawyer Susan Crawford, who allegedly bypassed the prosecution in order to meet an agreement with the defence made before the trial. Chief prosecutor Colonel Davis was unaware of the plea deal and surprised at the nine-month sentence, telling ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' "I wasn't considering anything that didn't have two digits", meaning a sentence of at least 10 years.

Ben Wizner

Ben Wizner (born 1971) is an American lawyer, writer, and civil liberties advocate with the American Civil Liberties Union. Since July 2013, he has been the lead attorney of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Education and personal life

Wizner ...

of the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

described the case as "an unwitting symbol of our shameful abandonment of the rule of law".

Political manipulation claims

Australian and US critics speculated that the one-year media ban was a condition requested by the Australian government and granted as a political favour. Senator Bob Brown of the

Australian and US critics speculated that the one-year media ban was a condition requested by the Australian government and granted as a political favour. Senator Bob Brown of the Australian Greens

The Australian Greens, commonly known as The Greens, are a confederation of Green state and territory political parties in Australia. As of the 2022 federal election, the Greens are the third largest political party in Australia by vote and th ...

said, "America's guarantee of free speech under its constitution would have rendered such a gag illegal in the U.S." The Law Council of Australia

The Law Council of Australia, founded in 1933, is an association of law societies and bar associations from the states and territories of Australia, and the peak body representing the legal profession in Australia. The Law Council represents mo ...

reported that the trial was "a contrived affair played out for the benefit of the media and the public", "designed to lay a veneer of due process over a political and pragmatic bargain", serving to corrode the rule of law. They referred to government support for the military tribunal process as shameful. In an interview, the prominent human rights lawyer and UN war crimes judge Geoffrey Robertson QC said that the pre-trial agreement "was obviously an expedient at the request of an Australian Government that needed to shore up votes". He went on to note that 'no one looks on he agreement

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

as a proper judicial procedure at all.';

The Pentagon

The Pentagon is the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. It was constructed on an accelerated schedule during World War II. As a symbol of the U.S. military, the phrase ''The Pentagon'' is often used as a metony ...

chief prosecutor

A prosecutor is a legal representative of the prosecution in states with either the common law adversarial system or the Civil law (legal system), civil law inquisitorial system. The prosecution is the legal party responsible for presenting the ...

Colonel Morris Davis, who had resigned from the US defence force citing dissatisfaction with the Guantanamo military commission process, alleged that the process had become highly politicised and that he had felt "pressured to do something less than full, fair and open". Davis later elaborated, saying that the Hicks trial was flawed and appeared rushed for the political benefit of the Howard

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

government in Australia. Davis said of his former superiors that "there is no question they wanted me to stage show trials that have nothing to do with the centuries-old tradition of military justice in America". On 28 April 2008, while testifying at a pre-trial hearing at Guantanamo for Salim Hamdan

Salim Ahmed Hamdan () (born February 25, 1968) is a Yemeni man, captured during the invasion of Afghanistan, declared by the United States government to be an illegal enemy combatant and held as a detainee at Guantanamo Bay from 2002 to November 2 ...

, Colonel Davis said that he had "inherited" the Hicks case but did not consider it serious enough to warrant prosecution.

In November 2007, allegations from an anonymous US military officer, that a high-level political agreement had occurred in the Hicks case, were reported. The officer said that "one of our staffers was present when Vice-President Cheney interfered directly to get Hicks's plea bargain deal. He did it apparently, as part of a deal cut with Howard". Australian Prime Minister John Howard denied any involvement in Hicks's plea bargain.

The Australian government