Dartmoor (HM Prison) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HM Prison Dartmoor is a Category C men's prison, located in

After all American and French prisoners had been released, paroled and repatriated, the gaol on Dartmoor was left unused for 35 years until 1850. Work then began to rebuild and recommission the prison for civilian convicts. It reopened in 1851. The POW remains that had been originally buried on the moor were exhumed and re-interred in two cemeteries behind the prison when the prison farm was established in about 1852.

During the

After all American and French prisoners had been released, paroled and repatriated, the gaol on Dartmoor was left unused for 35 years until 1850. Work then began to rebuild and recommission the prison for civilian convicts. It reopened in 1851. The POW remains that had been originally buried on the moor were exhumed and re-interred in two cemeteries behind the prison when the prison farm was established in about 1852.

During the

*

*

Dartmoor continues to suffer from its age, in 2001 a

Dartmoor continues to suffer from its age, in 2001 a

Ministry of Justice pages on DartmoorDartmoor Prison MuseumHMP Dartmoor - HM Inspectorate of Prisons Reports

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dartmoor (Hm Prison) Category C prisons in England Dartmoor Prisons in Devon 1809 establishments in England Museums in Devon Prison museums in the United Kingdom Men's prisons Grade II listed prison buildings Grade II listed buildings in Devon

Princetown

Princetown is a villageDespite its name, Princetown is not classed as a town today – it is not included in the County Council's list of the 29 towns in Devon: located within Dartmoor national park in the English county of Devon. It is the p ...

, high on Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous ...

in the English county of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devon is ...

. Its high granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained (phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies undergro ...

walls dominate this area of the moor

Moor or Moors may refer to:

Nature and ecology

* Moorland, a habitat characterized by low-growing vegetation and acidic soils.

Ethnic and religious groups

* Moors, Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and Malta during ...

. The prison is owned by the Duchy of Cornwall

The Duchy of Cornwall ( kw, Duketh Kernow) is one of two royal duchies in England, the other being the Duchy of Lancaster. The eldest son of the reigning British monarch obtains possession of the duchy and the title of 'Duke of Cornwall' at ...

, and is operated by His Majesty's Prison Service

His Majesty's Prison Service (HMPS) is a part of HM Prison and Probation Service (formerly the National Offender Management Service), which is the part of His Majesty's Government charged with managing most of the prisons within England and Wale ...

.

Dartmoor Prison was given Grade II heritage listing

This list is of heritage registers, inventories of cultural properties, natural and man-made, tangible and intangible, movable and immovable, that are deemed to be of sufficient heritage value to be separately identified and recorded. In many ...

in 1987.

History

POW prison

In 1805, the United Kingdom was at war with Napoleonic France, a conflict during which thousands of prisoners were taken and confined in prison "hulks" or derelict ships. This was considered unsafe, partially due to the proximity of the Royal Naval dockyard at Devonport (then called Plymouth Dock), and as living conditions were appalling in the extreme, a prisoner of war depot was planned in the remote isolation of Dartmoor. The prison was designed byDaniel Asher Alexander

Daniel Asher Alexander (6 May 1768 – 2 March 1846) was an English architect and engineer.

Life

Daniel Asher Alexander was born in Southwark, London and educated at St Paul's School, London. He was admitted to the Royal Academy Schools i ...

. Construction by local labour started in 1806, taking three years to complete. In 1809, the first French prisoners arrived and the prison was full by the end of the year.

From the spring of 1813 until March 1815, about 6,500 American sailors from the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

were imprisoned at Dartmoor in poor conditions (food was bad and the roofs leaked). These were either naval prisoners or impressed American seamen discharged from British vessels. Whilst the British were in overall charge of the prison, the prisoners created their own governance and culture. They had courts which meted out punishments, a market, a theatre and a gambling room. About 1,000 of the prisoners were Black. A recent examination of the General Entry Book of American Prisoners of War at Dartmoor, by Nicholas Guyatt, found "Eight Hundred and Twenty - Nine Sailors of Colour had been entered into the register by the end of October 1814."

Escapes

Unlike many eighteen century detention facilities, Dartmoor Prison was purpose built in an isolated location, ringed by high stone walls, and manned by hundreds of armed militia sentries. In addition a rope ran around the entire circumference of the prison, linked to a series of bells, which quickly spread an alarm. Even if a determined prisoner made it beyond the walls, he would still have to traverse ten miles on foot, over wild moorland and bogs, an area frequently beset with fog and chilling winds, to reach the nearest town. Local residents turning in an escapee could expect a reward of a guinea. Yet, despite these daunting odds, scholar Nicholas Guyatt has tallied a total of twenty-four American POWs successfully making their way to freedom. ;Disorder Although the war ended with theTreaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

on 24 December 1814, American prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

remained in Dartmoor because the British government refused to let them go on parole or take any steps until the treaty was ratified by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

on 17 February 1815. It took several weeks for the American agent to secure ships for their transportation home, and the men grew very impatient. On 4 April, a food contractor attempted to work off some damaged hardtack on them in place of soft bread and was forced to yield by their insurrection. The commandant, Captain T. G. Shortland, suspected them of a design to break out of the gaol. This was the reverse of the truth in general, as they would lose their chance of going on the ships, but a few had made threats of the sort, and the commandant was very uneasy.

At about 6:00 pm on 6 April, Shortland discovered a hole from one of the five prisons to the barrack yard near the gun racks. Some prisoners were outside the fence, noisily pelting each other with turf, and many more were near the breach (and the gambling tables), though the signal for return to prisons had sounded. Shortland was convinced of a plot and rang the alarm bell to collect the officers and have the guards ready. This precaution brought back a crowd just going to quarters. Just then a prisoner broke a gate chain with an iron bar and a number of the prisoners pressed through to the prison market square. After attempts at persuasion, Shortland ordered a charge which drove some of the prisoners in. Those near the gate, however, hooted at and taunted the soldiery, who fired a volley over their heads. The crowd yelled louder and threw stones, and the soldiers, probably without orders fired a direct volley which killed and wounded a large number. Then they continued firing at the prisoners, many of whom were now struggling to get back inside the blocks.

Finally the captain, a lieutenant and the hospital surgeon (the other officers being at dinner) succeeded in stopping the shooting and started caring for the wounded – about 60, 30 seriously, besides seven killed outright. The affair was examined by a joint commission, Charles King for the United States and F. S. Larpent for Great Britain, which exonerated Shortland, justified the initial shooting and blamed the subsequent deaths on unknown culprits. Following these findings, Shortland was rewarded with a promotion. Despite being labelled "The Dartmoor Massacre", the British government paid compensation to the American families of those killed and pensioned the disabled.

A memorial has been erected to the 271 POW

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

s (mostly seamen) who are buried in the prison grounds. By July 1815 at least 270 Americans and 1,200 French prisoners had died.

Closure and reopening

After all American and French prisoners had been released, paroled and repatriated, the gaol on Dartmoor was left unused for 35 years until 1850. Work then began to rebuild and recommission the prison for civilian convicts. It reopened in 1851. The POW remains that had been originally buried on the moor were exhumed and re-interred in two cemeteries behind the prison when the prison farm was established in about 1852.

During the

After all American and French prisoners had been released, paroled and repatriated, the gaol on Dartmoor was left unused for 35 years until 1850. Work then began to rebuild and recommission the prison for civilian convicts. It reopened in 1851. The POW remains that had been originally buried on the moor were exhumed and re-interred in two cemeteries behind the prison when the prison farm was established in about 1852.

During the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1917, criminals were removed from the gaol when it was converted into a Home Office Work Centre for conscientious objectors

A conscientious objector (often shortened to conchie) is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of thought, conscience, or religion. The term has also been extended to object ...

granted release from other prisons. The cells were left unlocked, inmates wore their own clothes and could go outside to visit the village in their off-duty time.

Notoriety

In 1920, the Dartmoor began housing UK criminals. It would develop a reputation for housing some of Britain's most serious offenders that included murderers, gangsters, thieves, spies, and robbers such as Jack “the Hat” McVitie, Jack “Spot” Comer,John George Haigh

John George Haigh (; 24 July 1909 – 10 August 1949), commonly known as the Acid Bath Murderer, was an English serial killer convicted for the murder of six people, although he claimed to have killed nine. Haigh battered to death or shot his ...

, and Frank Mitchell. Numerous escape attempts have been made by inmates to get out of the prison and onto the moors, leading to massive manhunts by the police and prison service. Instances of disobedience included a model prisoner attacking a popular guard with a razor blade and rough treatment by prisoners of a prisoner being removed to solitary.

;Mutiny

The prison's tough conditions eventually led to its worst outbreak of violence on 24 January 1932. The cause of the riots is generally attributed to prisoners' perceptions of poor quality of the food, not generally but on specific days prior to the disturbance when it was suspected it had been tampered with. At the parade later that day, 50 prisoners refused orders, and the rest were marched back to their cells but refused to enter. At this point, the prison governor and his staff fled to an unused part of the prison and secured themselves there. The prisoners then released those held in solitary. There was extensive damage to property, and a prisoner was shot by one of the staff, but no prison staff were injured. According to the du Parcq report into the riot: "Reinforcements arrived, and within fifteen minutes these 'vicious brutes', who for some two hours had terrorized well-armed prison staff, and effectively controlled the prison, had surrendered and been locked up again".

; Notable prisoners

*

*Michael Davitt

Michael Davitt (25 March 184630 May 1906) was an Irish republican activist for a variety of causes, especially Home Rule and land reform. Following an eviction when he was four years old, Davitt's family migrated to England. He began his caree ...

* Peter Hammond, founder of Hammond, Louisiana, US

*Fred Longden

Fred Longden (23 February 1894 – 5 October 1952) was a British Labour and Co-operative politician.

Born and brought up in Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, and educated at elementary school, he began work aged 13 as a moulder-apprentice, joinin ...

*John Rodker

John Rodker (18 December 1894 – 6 October 1955) was an English writer, modernist poet, and publisher of modernist writers.

Biography

John Rodker was born on 18 December 1894 in Manchester, into a Jewish immigrant family. The family moved t ...

*Moondyne Joe

Joseph Johns ( February 1826 – 13 August 1900), better known as Moondyne Joe, was an English convict and Western Australia's best-known bushranger. Born into poor and relatively difficult circumstances, he became something of a petty criminal ...

*Thomas William Jones, Baron Maelor

Thomas William Jones, Lord Maelor (10 February 1898 – 18 November 1984) was a British Labour politician.

Born into a mining family in Ponciau, Wrexham, Wales, he was educated at Ponciau School before becoming a coal miner at the nearby Bers ...

*John Boyle O'Reilly

John Boyle O'Reilly (28 June 1844 – 10 August 1890) was an Irish poet, journalist, author and activist. As a youth in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians, for which he was transported to Western Australia ...

*Arthur Owens

Arthur Graham Owens, later known as Arthur Graham White (14 April 1899 – 24 December 1976), was a Welsh double agent for the Allies during the Second World War. He was working for MI5 while appearing to the Abwehr (the German intelligence agency ...

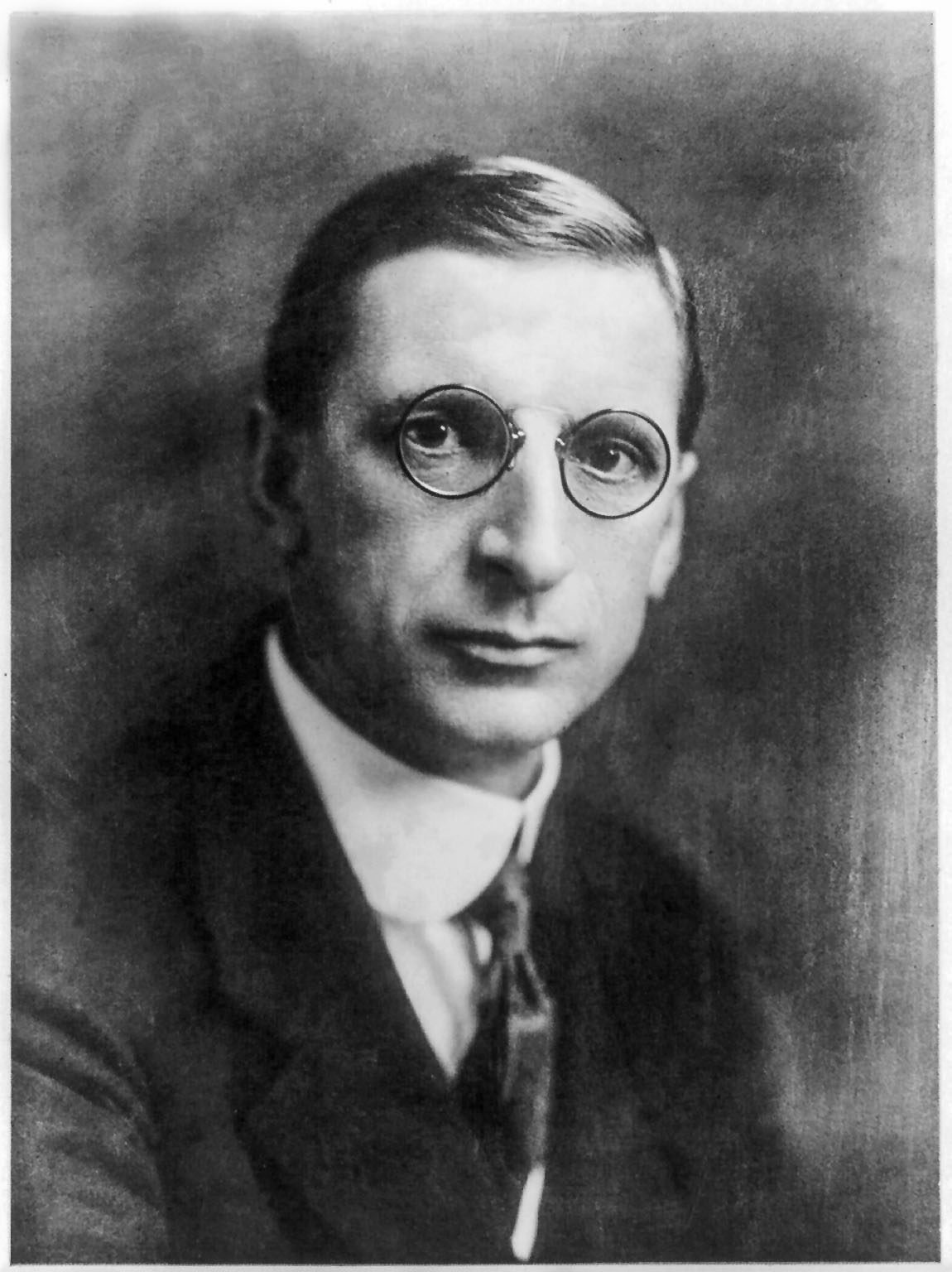

*Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

*F. Digby Hardy

John Henry Gooding, ''alias'' Frank Digby Hardy (5 April 1868 – 28 October 1930) was an English naval writer, journalist, soldier, career criminal and would-be spy during the Irish War of Independence. Born in Devonport, Plymouth to a middl ...

*John Williams

John Towner Williams (born February 8, 1932)Nylund, Rob (15 November 2022)Classic Connection review ''WBOI'' ("For the second time this year, the Fort Wayne Philharmonic honored American composer, conductor, and arranger John Williams, who wa ...

* Frank Mitchell

*Reginald Horace Blyth

Reginald Horace Blyth (3 December 1898–28 October 1964) was an English writer and devotee of Japanese culture. He is most famous for his writings on Zen and on haiku poetry.

Early life

Blyth was born in Essex, England, the son of a railway cl ...

* Darkie Hutton

*John George Haigh

John George Haigh (; 24 July 1909 – 10 August 1949), commonly known as the Acid Bath Murderer, was an English serial killer convicted for the murder of six people, although he claimed to have killed nine. Haigh battered to death or shot his ...

*Bruno Tolentino Bruno Lúcio de Carvalho Tolentino (November 12, 1940 – June 27, 2007) was a Brazilian poet and intellectual, known for his opposition towards the more blatant avant-garde elements of Brazilian modernism, his advocacy of classical forms and subjec ...

, who eventually was deported to Brazil where the major part of his oeuvre was published. ''"A Balada do Cárcere"'' (1996) is a poetic recollection of the time spent in Dartmoor.

*Fahad Mihyi, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary soci ...

terrorist behind the 1978 London bus attack

* Aravindan Balakrishnan

Modern operations

Dartmoor continues to suffer from its age, in 2001 a

Dartmoor continues to suffer from its age, in 2001 a Board of Visitors

In the United States, a board often governs institutions of higher education, including private universities, state universities, and community colleges. In each US state, such boards may govern either the state university system, individual col ...

report condemned sanitation, as well as highlighting a list of urgent repairs needed. A year later, the prison was converted to a Category C prison for less violent offenders. In 2002, the Prison Reform Trust

The Prison Reform Trust (PRT) was founded in 1981 in London, England, by a small group of prison reform campaigners who were unhappy with the direction in which the Howard League for Penal Reform was heading, concentrating more on community punish ...

warned that the prison may be breaching the Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 1998 (c. 42) is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom which received royal assent on 9 November 1998, and came into force on 2 October 2000. Its aim was to incorporate into UK law the rights contained in the European Con ...

due to severe overcrowding at the jail. A year later, however, the Chief Inspector of Prisons declared that the prison had made substantial improvements to its management and regime.

In March 2008, staff at the prison passed a vote of no confidence

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in the governor Serena Watts, claiming they felt bullied by managers and unsafe.

Dartmoor is now a Category C prison, which means it houses mainly non-violent offenders and white-collar criminals. It also holds people with convictions for sexual offences, but it is designated as a support site only for these individuals and as such does not offer treatment programmes for them.

Dartmoor offers cell accommodation on six wings. Education is available at the prison (full and part-time), and ranges from basic educational skills to Open University

The Open University (OU) is a British public research university and the largest university in the United Kingdom by number of students. The majority of the OU's undergraduate students are based in the United Kingdom and principally study off- ...

courses. Vocational training includes electronics

The field of electronics is a branch of physics and electrical engineering that deals with the emission, behaviour and effects of electrons using electronic devices. Electronics uses active devices to control electron flow by amplification ...

, brickwork

Brickwork is masonry produced by a bricklayer, using bricks and mortar. Typically, rows of bricks called '' courses'' are laid on top of one another to build up a structure such as a brick wall.

Bricks may be differentiated from blocks by s ...

and carpentry

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters tr ...

courses up to City & Guilds

The City and Guilds of London Institute is an educational organisation in the United Kingdom. Founded on 11 November 1878 by the City of London and 16 livery companies – to develop a national system of technical education, the institute has ...

and NVQ

National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) are practical work-based awards in England, Wales and Northern Ireland that are achieved through assessment and training. The regulatory framework supporting NVQs was withdrawn in 2015 and replaced by the ...

level, Painting and Decorating

A house painter and decorator is a tradesman responsible for the painting and decorating of buildings, and is also known as a decorator or house painter.''The Modern Painter and Decorator'' volume 1 1921 Caxton The purpose of painting is to imp ...

courses, industrial cleaning and desktop publishing

Desktop publishing (DTP) is the creation of documents using page layout software on a personal ("desktop") computer. It was first used almost exclusively for print publications, but now it also assists in the creation of various forms of online c ...

. Full-time employment is also available in catering, farming, gardening, laundry, textiles, Braille

Braille (Pronounced: ) is a tactile writing system used by people who are visually impaired, including people who are Blindness, blind, Deafblindness, deafblind or who have low vision. It can be read either on Paper embossing, embossed paper ...

, contract services, furniture manufacturing and polishing

Polishing is the process of creating a smooth and shiny surface by rubbing it or by applying a chemical treatment, leaving a clean surface with a significant specular reflection (still limited by the index of refraction of the material accordin ...

. Employment is supported with NVQ or City & Guilds vocational qualifications. All courses and qualifications at Dartmoor are operated by South Gloucestershire and Stroud College

South Gloucestershire and Stroud College, also known as SGS College, is a college of further education and higher education based in South Gloucestershire and Stroud, England. It was established in February 2012 following the merger of Filton Co ...

and Cornwall College

The Cornwall College Group (TCCG; kw, Kolji Kernow) is a further education college situated on eight sites throughout Cornwall and Devon, England, United Kingdom, with its head office in St Austell.

Campuses

There are eight campuses within ...

.

The " Dartmoor Jailbreak" is a yearly event, in which members of the public "escape" from the prison and must travel as far as possible in four days, without directly paying for transport. By doing so they raise money for charity.

In September 2013, it was announced that discussions would commence with the Duchy of Cornwall about the long-term future of HMP Dartmoor. In January 2014 it was stated on the BBC news website that the notice period with the Duchy for closing is 10 years. In November 2015 the Ministry of Justice confirmed that, as part of a major programme to replace older prisons, it would not renew its lease on the prison.

It was announced in October 2019 that HMP Dartmoor would close in 2023, but in December 2021 it was confirmed that, following negotiations with the Duchy, it would remain open beyond 2023 and for the foreseeable future.

Dartmoor Prison Museum

The Dartmoor Prison Museum, located in the old dairy buildings, focuses on the history of HMP Dartmoor. Exhibits include the prison's role in housingprisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

from the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

and the War of 1812, manacles

Handcuffs are restraint devices designed to secure an individual's wrists in proximity to each other. They comprise two parts, linked together by a chain, a hinge, or rigid bar. Each cuff has a rotating arm which engages with a ratchet that ...

and weapons, memorabilia, clothing and uniforms, famous prisoners, and the changed focus of the prison. It also sells (2015) garden ornaments and other items made in the prison concrete and carpentry shops by prisoners engaged in educational courses.

There are also displays and information on less well known aspects of the prison such as the incarceration of conscientious objectors during World War One.

In popular culture

*In the 1963 James Bond film '' From Russia with Love'', the main villainous henchman,SPECTRE

Spectre, specter or the spectre may refer to:

Religion and spirituality

* Vision (spirituality)

* Apparitional experience

* Ghost

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Spectre'' (1977 film), a made-for-television film produced and writ ...

assassin Red Grant

Red is the color at the long wavelength end of the visible spectrum of light, next to orange and opposite violet. It has a dominant wavelength of approximately 625–740 nanometres. It is a primary color in the RGB color model and a secondary ...

(played by Robert Shaw) is described as a psychopathic paranoid and a convicted murderer, who once escaped from Dartmoor Prison.

*The adventure story ''A Rogue by Compulsion. An Affair of the Secret Service'' (1915) by Victor Bridges

Victor Bridges (real name Victor George de Freyne, 14 March 1878 – 29 November 1972) was a prolific English author of detective and fantasy fiction, and also a playwright and occasional poet.

Life

Born on 14 March 1878 at Clifton, Bristol, Vic ...

begins with a dramatic escape from Dartmoor.

*In '' Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)'', Mr. Christian states to Captain Bligh that Seaman Burkitt chose service in the Royal Navy as an alternative to imprisonment at Dartmoor.

*In the John Galsworthy play, ''Escape

Escape or Escaping may refer to:

Computing

* Escape character, in computing and telecommunication, a character which signifies that what follows takes an alternative interpretation

** Escape sequence, a series of characters used to trigger some so ...

'', Dartmoor is the prison whence the hero, Captain Denman escapes. The stage production in 1927 starred Leslie Howard and the 1930 film version starred Sir Gerald du Maurier.

*The 1929 movie ''A Cottage on Dartmoor

''A Cottage on Dartmoor'' (a.k.a. ''Escape from Dartmoor'') is a 1929 British silent film, directed by Anthony Asquith and starring Norah Baring, Uno Henning and Hans Adalbert Schlettow. The cameraman was Stanley Rodwell.

It was the last of A ...

'' begins with an escapee from Dartmoor prison, and proceeds to a flashback as to how he came to be incarcerated.

*An escaped convict from Dartmoor figures in Nevil Shute

Nevil Shute Norway (17 January 189912 January 1960) was an English novelist and aeronautical engineer who spent his later years in Australia. He used his full name in his engineering career and Nevil Shute as his pen name, in order to protect h ...

's first novel ''Marazan

''Marazan'' is the first published novel by the British author Nevil Shute. It was originally published in 1926 by Cassell & Co, then republished in 1951 by William Heinemann. The events of the novel occur, in part, around the Isles of Scilly.

...

'', published in 1926.

*''Decline and Fall

''Decline and Fall'' is a novel by the English author Evelyn Waugh, first published in 1928. It was Waugh's first published novel; an earlier attempt, titled '' The Temple at Thatch'', was destroyed by Waugh while still in manuscript form. '' ...

'', a novel by Evelyn Waugh

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (; 28 October 1903 – 10 April 1966) was an English writer of novels, biographies, and travel books; he was also a prolific journalist and book reviewer. His most famous works include the early satires ''Decli ...

, first published in 1928 makes thinly disguised references to Dartmoor Prison.

*Dartmoor Prison is mentioned in ''The Thirteen Problems

''The Thirteen Problems'' is a short story collection by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the UK by Collins Crime Club in June 1932Chris Peers, Ralph Spurrier and Jamie Sturgeon. ''Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First E ...

'', a short story collection written by Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English writer known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving around fictiona ...

, and first published in 1932. Christie's ''The Sittaford Mystery

''The Sittaford Mystery'' is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in 1931 under the title of ''The Murder at Hazelmoor'' and in UK by the Collins Crime Club on 7 Sept ...

'' (1931) is set on Dartmoor and features an escaped prisoner.

*Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Ho ...

made reference to 'Princetown Prison' in four stories that he wrote between 1890 and 1903. In ''The Hound of the Baskervilles'' (1902), an escaped prisoner from Princetown serves as a red herring for Holmes and Watson.

*'' Dressed to Kill'', a 1946 Sherlock Holmes

Sherlock Holmes () is a fictional detective created by British author Arthur Conan Doyle. Referring to himself as a " consulting detective" in the stories, Holmes is known for his proficiency with observation, deduction, forensic science and ...

film uses Dartmoor Prison in the plot as the supposed location where three music boxes were made that contain a secret code for a criminal gang.

*Referenced in Bob Miller's song, ''Twenty-One Years''.

*In the ''Tales of Old Dartmoor'' episode (recorded in 1956) of The Goons

''The Goon Show'' is a British radio comedy programme, originally produced and broadcast by the BBC Home Service from 1951 to 1960, with occasional repeats on the BBC Light Programme. The first series, broadcast from 28 May to 20 September 19 ...

radio comedy series, Grytpype-Thynne arranges for the prison to put to sea to visit the Château d'If

The Château d'If () is a fortress located on the Île d'If, the smallest island in the Frioul archipelago, situated about offshore from Marseille in southeastern France. Built in the 16th century, it later served as a prison until the end o ...

in France as part of a plan to find the treasure of the Count of Monte Cristo hid there. A cardboard replica is left in its place, which is left standing after the original Dartmoor Prison sinks with all hands at the end of the episode.

*In an episode of ''The Saint

The Saint may refer to:

Fiction

* Simon Templar, also known as "The Saint", the protagonist of a book series by Leslie Charteris and subsequent adaptations:

** ''The Saint'' (film series) (1938–43), starring Louis Hayward, George Sanders an ...

'' television series entitled "Escape Route" (1966), Simon Templar

''The Saint'' is the nickname of the fictional character Simon Templar, featured in a series of novels and short stories by Leslie Charteris published between 1928 and 1963. After that date, other authors collaborated with Charteris on books unt ...

(Roger Moore

Sir Roger George Moore (14 October 192723 May 2017) was an English actor. He was the third actor to portray fictional British secret agent James Bond in the Eon Productions film series, playing the character in seven feature films between 19 ...

) is sent to Dartmoor to uncover a planned escape.

*Comedy band The Barron Knights

The Barron Knights are a British humorous pop rock group, originally formed in 1959 in Leighton Buzzard, Bedfordshire,Colin Larkin, ''Virgin Encyclopedia of Sixties Music'', (Muze UK Ltd, 1997), ), p. 32 as the Knights of the Round Table.

C ...

' 1978 UK No. 3 hit single "A Taste of Aggro", a medley of parodies, included a version of "The Smurf Song" featuring, in place of the Smurfs

''The Smurfs'' (french: Les Schtroumpfs; nl, De Smurfen) is a Belgian comic franchise centered on a fictional colony of small, blue, humanoid creatures who live in mushroom-shaped houses in the forest. ''The Smurfs'' was first created and int ...

, a group of bank robbers from Catford

Catford is a district in south east London, England, and the administrative centre of the London Borough of Lewisham. It is southwest of Lewisham itself, mostly in the Rushey Green (ward), Rushey Green and Catford South Ward (electoral subdiv ...

who have escaped from Dartmoor Prison.

*Dartmoor is mentioned several times in the British comedy series ''You Rang, M'Lord?

''You Rang, M'Lord?'' is a BBC television sitcom written by Jimmy Perry and David Croft, the creators of ''Dad's Army''. It was broadcast between 1990 and 1993 on the BBC (although there had earlier been a pilot episode in 1988). The show was s ...

'', especially in connection with the scheming butler, Alf Stokes, who mentions on multiple occasions that he will end up in Dartmoor.

*In 1988, the prison played host to a storyline in ''EastEnders

''EastEnders'' is a Television in the United Kingdom, British soap opera created by Julia Smith (producer), Julia Smith and Tony Holland which has been broadcast on BBC One since February 1985. Set in the fictional borough of Walford in the Ea ...

'', where Den Watts

Dennis "Den" Watts is a fictional character from the BBC soap opera '' EastEnders'', played by actor Leslie Grantham. He became well known for his tabloid nickname, "Dirty Den".

Den was the original landlord of The Queen Victoria public house ...

(played by Leslie Grantham

Leslie Michael Grantham (30 April 1947 – 15 June 2018) was an English actor, best known for his role as "Dirty" Den Watts in the BBC soap opera ''EastEnders''. He was a convicted murderer, having served 10 years for the killing of a West Germ ...

) was being held on remand for arson. He was also joined for some of the storyline by Nick Cotton

Nick Cotton is a fictional character from the British soap opera ''EastEnders'' played by John Altman on a semi-regular basis from the soap's debut episode on 19 February 1985. Altman has stated that his initial exit was due to producer Julia ...

(played by John Altman), who was imprisoned for a different offence. The prison was called Dickens Hill

Dickens Hill is a fictional prison in the BBC soap opera ''EastEnders''. The prison is part of a storyline that first aired between 1988 and 1989. The storyline centres on the popular character Den Watts and was filmed on location at Dartmoor P ...

.

*Dartmoor is frequently mentioned in the ''Agent Z

Agent may refer to:

Espionage, investigation, and law

*, spies or intelligence officers

* Law of agency, laws involving a person authorized to act on behalf of another

** Agent of record, a person with a contractual agreement with an insuranc ...

'' series of comical children's books written by Mark Haddon

Mark Haddon (born 28 October 1962) is an English novelist, best known for ''The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time'' (2003). He won the Whitbread Award, the Dolly Gray Children's Literature Award, Guardian Prize, and a Commonwealth Wr ...

.

*Dartmoor prison is implicated in the local Dartmoor 'Hairy hands

The Hairy Hands is a ghost story/legend that built up around a stretch of road on a remote area of Dartmoor in the English county of Devon, which was purported to have seen an unusually high number of motor vehicle accidents during the early 20th ...

' ghost story

A ghost story is any piece of fiction, or drama, that includes a ghost, or simply takes as a premise the possibility of ghosts or characters' belief in them."Ghost Stories" in Margaret Drabble (ed.), ''Oxford Companion to English Literature'' ...

/legend

A legend is a Folklore genre, genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived, both by teller and listeners, to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human valu ...

.

*Dartmoor prison plays a central role in ''The Lively Lady'', American author Kenneth Roberts' 1931 historical novel taking place during The War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

*In the first episode of the second series of ''James May's Man Lab

''James May's Man Lab'' is a British television series presented by former Top Gear presenter James May. The first, three-part series was aired on BBC Two between 31 October and 14 November 2010. The second, five-part series was aired between 2 ...

'', James May

James Daniel May (born 16 January 1963) is an English television presenter and journalist. He is best known as a co-presenter of the motoring programme ''Top Gear (2002 TV series), Top Gear'' alongside Jeremy Clarkson and Richard Hammond from ...

and Oz Clarke

Robert Owen Clarke (born 1949), known as Oz Clarke, is a British wine writer, actor, television presenter and broadcaster.

Early life

Clarke's parents were a chest physician and a nursing sister. He is of Irish descent and was brought up Roman ...

were demonstrating map-reading skills by pretending to escape from Dartmoor prison and cross Dartmoor

Dartmoor is an upland area in southern Devon, England. The moorland and surrounding land has been protected by National Park status since 1951. Dartmoor National Park covers .

The granite which forms the uplands dates from the Carboniferous ...

to their escape car (although they had to start their escape from outside the prison grounds as they were not allowed permission inside the prison).

*One of the intersecting story lines in Edward Marston's novel, ''Shadow of the Hangman'' (2013) involves two American seamen who escape during the 1815 riot.

*The prison and the American sailors imprisoned towards the end of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

are central to Simon Mayo

Simon Andrew Hicks Mayo (born 21 September 1958) is an English radio presenter and author who worked for BBC Radio from 1982 until 2022.

Mayo has presented across three BBC stations for extended periods. From 1986 to 2001 he worked for Radio ...

's 2018 novel ''Mad Blood Stirring''.

*In ''The Voice of Terror

''Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror'' is a 1942 American mystery film, mystery thriller film based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes detective stories. The film combines elements of Doyle's short story "His Last Bow (story), His L ...

'' (1942), Sherlock Holmes is angrily confronted in a tavern by an ex-convict who says he had been sent to Dartmoor Prison by Holmes.

References

External links

Ministry of Justice pages on Dartmoor

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dartmoor (Hm Prison) Category C prisons in England Dartmoor Prisons in Devon 1809 establishments in England Museums in Devon Prison museums in the United Kingdom Men's prisons Grade II listed prison buildings Grade II listed buildings in Devon