Cyril Newall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

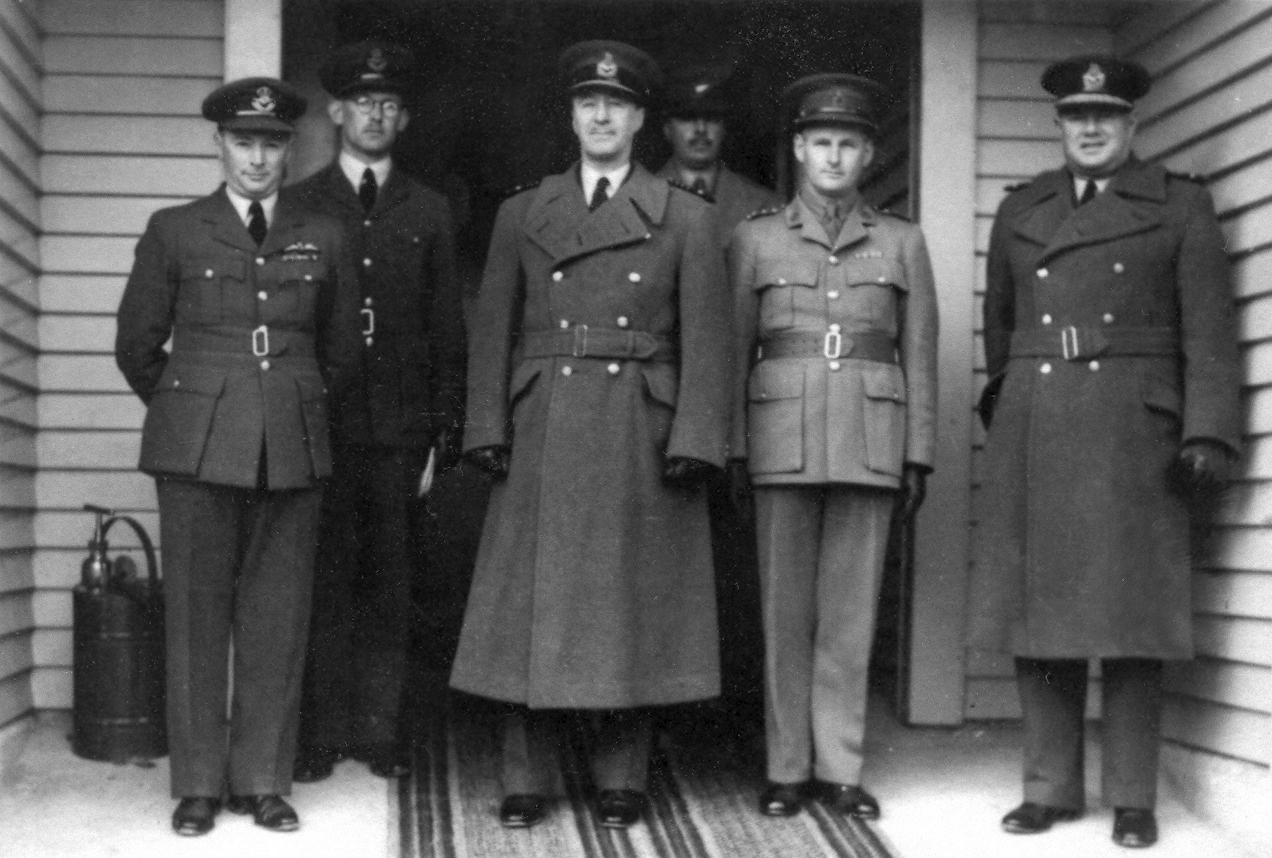

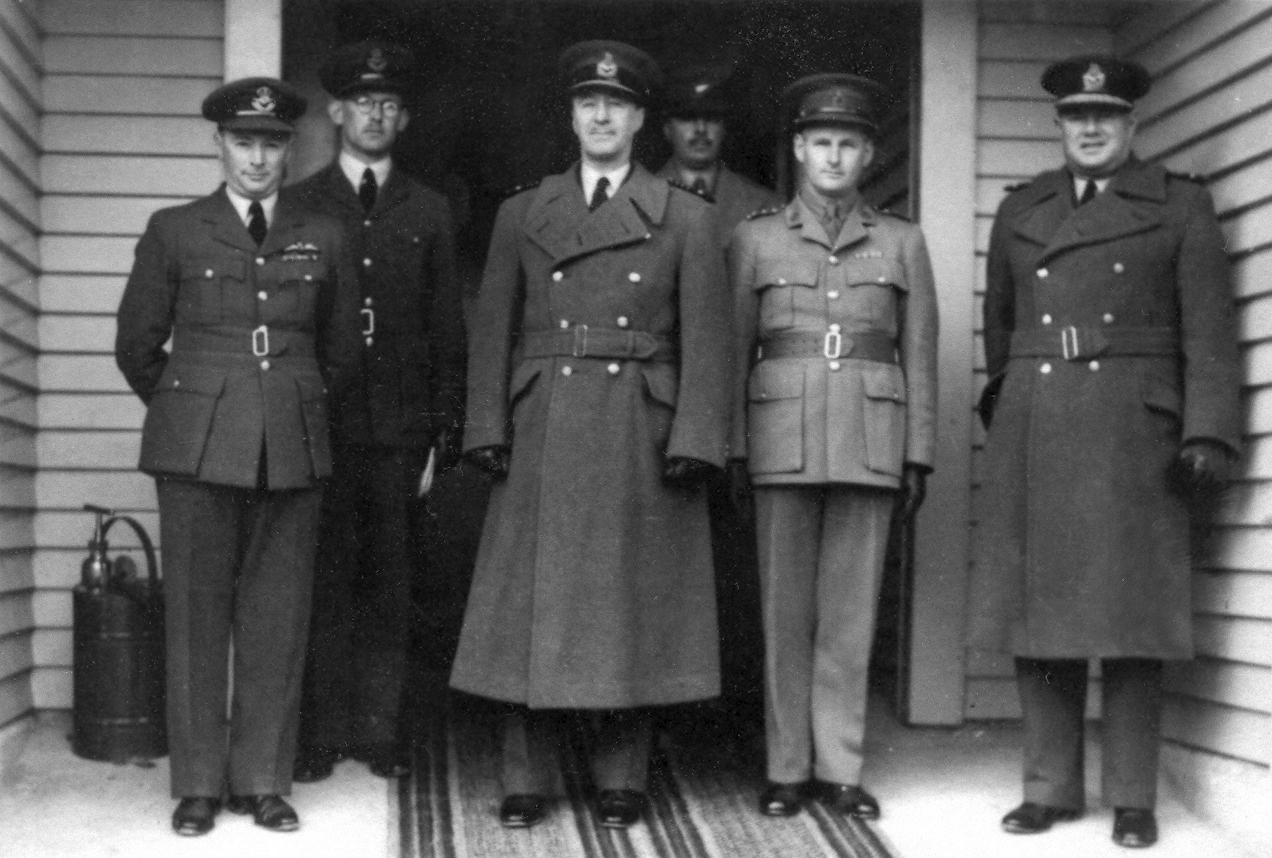

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Cyril Louis Norton Newall, 1st Baron Newall, (15 February 1886 – 30 November 1963) was a senior officer of the

Newall was granted a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force as a lieutenant colonel on 1 August 1919 and promoted to

Newall was granted a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force as a lieutenant colonel on 1 August 1919 and promoted to

On 1 September 1937, Newall was appointed as Chief of the Air Staff, the military head of the RAF, in succession to Sir

On 1 September 1937, Newall was appointed as Chief of the Air Staff, the military head of the RAF, in succession to Sir  During 1936 and 1937, the Air Staff had been fighting with the Cabinet over the rearmament plans; the Air Staff wanted a substantial bomber force and only minor increases in fighters, whilst the Minister for Defence Co-ordination, Thomas Inskip, successfully pushed for a greater role for the fighter force. Newall was promoted during the middle of this debate, and proved perhaps more flexible than might have been expected. In 1938 he supported sharp increases in aircraft production, including double-shift working and duplication of factories, and pushed for the creation of a dedicated organisation to repair and refit damaged aircraft. He supported expenditure on the new, heavily armed,

During 1936 and 1937, the Air Staff had been fighting with the Cabinet over the rearmament plans; the Air Staff wanted a substantial bomber force and only minor increases in fighters, whilst the Minister for Defence Co-ordination, Thomas Inskip, successfully pushed for a greater role for the fighter force. Newall was promoted during the middle of this debate, and proved perhaps more flexible than might have been expected. In 1938 he supported sharp increases in aircraft production, including double-shift working and duplication of factories, and pushed for the creation of a dedicated organisation to repair and refit damaged aircraft. He supported expenditure on the new, heavily armed,

In February 1941 Newall was appointed

In February 1941 Newall was appointed

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurkha ...

and Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

. He commanded units of the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

and Royal Air Force in the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, and served as Chief of the Air Staff during the first years of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. From 1941 to 1946 he was the Governor-General of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand ( mi, te kāwana tianara o Aotearoa) is the Viceroy, viceregal representative of the Monarchy of New Zealand, monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 ...

.

Born to a military family, Newall studied at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infant ...

, before taking a commission as a junior officer in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in 1905. After transferring to the 2nd Gurkha Rifles

The 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) was a rifle regiment of the British Indian Army before being transferred to the British Army on India's independence in 1947. The 4th Battalion joined the Indian Army as the 5th Ba ...

in the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the Land warfare, land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Arm ...

, he saw active service on the North West Frontier, but after learning to fly in 1911 turned towards a career in military aviation. During the First World War he rose from flying instructor to command of 41st Wing RFC, the main strategic bombing force, and was awarded the Albert Medal for putting out a fire in an explosives store.

He served in staff positions through the 1920s and was Air Officer Commanding the Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

in the early 1930s before becoming Air Member for Supply and Organisation

The Air Member for Materiel is the senior Royal Air Force officer responsible for procurement matters. The post-holder is a member of the Air Force Board and is in charge of all aspects of procurement and organisation for RAF regular, reserve and ...

in 1935. Newall was appointed Chief of the Air Staff in 1937 and, in that role, supported sharp increases in aircraft production, increasing expenditure on the new, heavily armed, Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

and Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

fighters, essential to re-equip Fighter Command. However, he was sacked after the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

after political intrigue caused him to lose Churchill's confidence. In 1941 he was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand, holding office until 1946.

Early life

Newall was born to Lieutenant Colonel William Potter Newall and Edith Gwendoline Caroline Newall (née Norton). After education atBedford School

:''Bedford School is not to be confused with Bedford Girls' School, Bedford High School, Bedford Modern School, Old Bedford School in Bedford, Texas or Bedford Academy in Bedford, Nova Scotia.''

Bedford School is a public school (English ind ...

, he attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst

The Royal Military College (RMC), founded in 1801 and established in 1802 at Great Marlow and High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, England, but moved in October 1812 to Sandhurst, Berkshire, was a British Army military academy for training infant ...

. After leaving Sandhurst, he was commissioned into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment on 16 August 1905. He was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often ...

on 18 November 1908, and transferred to the 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles

The 2nd King Edward VII's Own Gurkha Rifles (The Sirmoor Rifles) was a rifle regiment of the British Indian Army before being transferred to the British Army on India's independence in 1947. The 4th Battalion joined the Indian Army as the 5th Bat ...

on 16 September 1909. He served on the North-West Frontier, where he first encountered his future colleague Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

; at an exercise in 1909, Dowding's artillery section ambushed Newall's Gurkhas whilst they were still breakfasting.

Newall began to turn towards a career in aviation in 1911, when he learned to fly in a Bristol Biplane at Larkhill

Larkhill is a garrison town in the civil parish of Durrington, Wiltshire, England. It lies about west of the centre of Durrington village and north of the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge. It is about north of Salisbury.

The settlement ...

whilst on leave in England. He held certificate No. 144 issued by the Royal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

. He later passed a formal course at the Central Flying School

The Central Flying School (CFS) is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 at the Upavon Aerodrome, it is the longest existing flying training school. The school was based at ...

, Upavon

Upavon is a rural village and civil parish in the county of Wiltshire, England. As its name suggests, it is on the upper portion of the River Avon which runs from north to south through the village. It is on the north edge of Salisbury Plain ...

in 1913, and began working as a pilot trainer there from 17 November 1913; it was intended that he would form part of a flight training school to be established in India, but he had not yet left England when the First World War broke out.

First World War

On the outbreak of war, Newall was in England. On 12 September 1914, he was given the temporary rank ofcaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, and attached to the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

as a flight commander, to serve with No. 1 Squadron on the Western Front Western Front or West Front may refer to:

Military frontiers

* Western Front (World War I), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (World War II), a military frontier to the west of Germany

*Western Front (Russian Empire), a maj ...

. He was promoted to the permanent rank of captain on 22 September, effective from 16 August. On 24 March 1915 he was promoted to major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

and appointed to command No. 12 Squadron, flying BE2c aircraft in France from September onwards. The squadron took part in the Battle of Loos

The Battle of Loos took place from 1915 in France on the Western Front, during the First World War. It was the biggest British attack of 1915, the first time that the British used poison gas and the first mass engagement of New Army units. Th ...

, bombing railways and carrying out reconnaissance missions in October 1915.Probert, p. 15

On taking command of the squadron, he chose to stop flying personally in order to concentrate on administration, a decision which was regarded dismissively by his men; relations were strained until January 1916, when he demonstrated his courage by walking into a burning bomb store to try to control a fire. He was awarded the Albert Medal for this act on the personal recommendation of General Hugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

, and in February 1916 was promoted to lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colon ...

and given command of Training No. 6 Wing in England. In December 1916 he took command of No. 9 Wing in France, a long-range bomber and reconnaissance formation, and in October 1917 took command of the newly formed No. 41 Wing. This was upgraded as the 8th Brigade in December, with Newall promoted accordingly to the temporary rank of brigadier-general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed t ...

on 28 December 1917. During 1918, it joined the Independent Bombing Force, which was the main strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

arm of the newly formed Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

. In June 1918 Newall was appointed the Deputy Commander of the Independent Bombing Force, serving under Trenchard.

Newall was awarded the Croix d'Officier of the French Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleo ...

on 10 October 1918, and appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

on 1 January 1919, a Commander of the Order of the British Empire

The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire is a British order of chivalry, rewarding contributions to the arts and sciences, work with charitable and welfare organisations,

and public service outside the civil service. It was established ...

on 3 June 1919 and an Officer of the Belgian Order of Leopold on 18 April 1921.

Between the wars

Newall was granted a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force as a lieutenant colonel on 1 August 1919 and promoted to

Newall was granted a permanent commission in the Royal Air Force as a lieutenant colonel on 1 August 1919 and promoted to group captain

Group captain is a senior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force, where it originated, as well as the air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. It is sometimes used as the English translation of an equivalent rank i ...

on 8 August 1919. He became Deputy Director of Personnel at the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of Stat ...

in August 1919 and then Deputy Commandant of the apprentices' technical training school in August 1922. He married Mary Weddell in 1922; she died in September 1924, and he remarried the following year to Olive Foster, an American woman. He had three children with Foster, a son and two daughters.

Newall was promoted to air commodore on 1 January 1925, and took command of the newly formed Auxiliary Air Force

The Royal Auxiliary Air Force (RAuxAF), formerly the Auxiliary Air Force (AAF), together with the Air Force Reserve, is a component of His Majesty's Reserve Air Forces (Reserve Forces Act 1996, Part 1, Para 1,(2),(c)). It provides a primary rein ...

in May 1925. He was appointed to a League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

disarmament committee in December 1925 and then became Deputy Chief of the Air Staff Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (DCAS) may refer to:

* Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (Australia)

* Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (India)

* Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (Pakistan)

* Deputy Chief of the Air Staff (United Kingdom)

The Deputy Chief ...

and Director of Operations and Intelligence on 12 April 1926. He was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregiv ...

in the 1929 Birthday Honours

The King's Birthday Honours 1929 were appointments by King George V to various orders and honours to reward and highlight good works by members of the British Empire. The appointments were made to celebrate the official birthday of The King. The ...

and, having been promoted to air vice marshal

Air vice-marshal (AVM) is a two-star air officer rank which originated in and continues to be used by the Royal Air Force. The rank is also used by the air forces of many countries which have historical British influence and it is sometimes u ...

on 1 January 1930, he stood down as Deputy Chief on 6 February 1931. He became Air Officer Commanding Wessex Bombing Area in February 1931 and then Air Officer Commanding Middle East Command

Middle East Command, later Middle East Land Forces, was a British Army Command established prior to the Second World War in Egypt. Its primary role was to command British land forces and co-ordinate with the relevant naval and air commands to ...

in September 1931. He then returned to the Air Ministry, where he became Air Member for Supply and Organisation

The Air Member for Materiel is the senior Royal Air Force officer responsible for procurement matters. The post-holder is a member of the Air Force Board and is in charge of all aspects of procurement and organisation for RAF regular, reserve and ...

on 14 January 1935, during the beginnings of the pre-war expansion and rearmament. He was advanced to Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

in the 1935 Birthday Honours and promoted to air marshal on 1 July 1935. He attended the funeral of King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Qu ...

in January 1936.

Philosophically, Newall remained a close follower of Trenchard during the interwar period; his time in the Independent Bombing Force had left him convinced that strategic bombing was an exceptionally powerful weapon, and one that could not effectively be defended against. In this, he was a supporter of the standard doctrine of the day, which suggested that the destructive power of a bomber force was sufficiently great that it could cripple an industrial economy in short order, and that so merely its ''presence'' could potentially serve as an effective deterrent. He was promoted to air chief marshal

Air chief marshal (Air Chf Mshl or ACM) is a high-ranking air officer originating from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence. An air chief marshal is equivalent to an Admi ...

on 1 April 1937.

Chief of the Air Staff

On 1 September 1937, Newall was appointed as Chief of the Air Staff, the military head of the RAF, in succession to Sir

On 1 September 1937, Newall was appointed as Chief of the Air Staff, the military head of the RAF, in succession to Sir Edward Ellington

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Edward Leonard Ellington, (30 December 1877 – 13 June 1967) was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force. He served in the First World War as a staff officer and then as director-general of military aeronau ...

. The promotion was unexpected; of the prospective candidates mooted for the job, Newall has been widely seen by historians as the least gifted. The most prominent candidate was Hugh Dowding

Air Chief Marshal Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, 1st Baron Dowding, (24 April 1882 – 15 February 1970) was an officer in the Royal Air Force. He was Air Officer Commanding RAF Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain and is generally c ...

, the head of RAF Fighter Command

RAF Fighter Command was one of the commands of the Royal Air Force. It was formed in 1936 to allow more specialised control of fighter aircraft. It served throughout the Second World War. It earned near-immortal fame during the Battle of Brita ...

and senior in rank to Newall by three months, who had been informally told by Ellington in 1936 that he was expected to be appointed as the new Chief of the Air Staff. The decision was taken by the Air Minister, Viscount Swinton

A viscount ( , for male) or viscountess (, for female) is a title used in certain European countries for a noble of varying status.

In many countries a viscount, and its historical equivalents, was a non-hereditary, administrative or judicial ...

, without consulting Ellington for advice.

During 1936 and 1937, the Air Staff had been fighting with the Cabinet over the rearmament plans; the Air Staff wanted a substantial bomber force and only minor increases in fighters, whilst the Minister for Defence Co-ordination, Thomas Inskip, successfully pushed for a greater role for the fighter force. Newall was promoted during the middle of this debate, and proved perhaps more flexible than might have been expected. In 1938 he supported sharp increases in aircraft production, including double-shift working and duplication of factories, and pushed for the creation of a dedicated organisation to repair and refit damaged aircraft. He supported expenditure on the new, heavily armed,

During 1936 and 1937, the Air Staff had been fighting with the Cabinet over the rearmament plans; the Air Staff wanted a substantial bomber force and only minor increases in fighters, whilst the Minister for Defence Co-ordination, Thomas Inskip, successfully pushed for a greater role for the fighter force. Newall was promoted during the middle of this debate, and proved perhaps more flexible than might have been expected. In 1938 he supported sharp increases in aircraft production, including double-shift working and duplication of factories, and pushed for the creation of a dedicated organisation to repair and refit damaged aircraft. He supported expenditure on the new, heavily armed, Hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

and Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

fighters, essential to re-equip Fighter Command. He even began to distance himself, albeit slightly, from orthodox bomber philosophy, noting to the Minister for Air that "no one can say with absolute certainty that a nation can be knocked out from the air, because no-one has yet attempted it". Discussing plans for reacting to a war with Italy, in early 1939, he opposed a French proposal to force Italy's surrender by the use of heavy bombing raids against the north, arguing that it would be unlikely to force the country out of the war without the need for ground combat.

Newall was advanced to Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as one ...

in the 1938 Birthday Honours. He was still Chief of the Air Staff at the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939; his main contribution to the war effort was his successful resistance to the transfer of fighter squadrons to aid the collapsing French thus preserving a large portion of Fighter Command which would become crucial during the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

. While he remained committed to the idea of a " knock-out blow" offensive by Bomber Command

Bomber Command is an organisational military unit, generally subordinate to the air force of a country. The best known were in Britain and the United States. A Bomber Command is generally used for strategic bombing (although at times, e.g. during t ...

, he also recognised that it was too weak to do so successfully, but still strongly opposed the use of the RAF for close air support

In military tactics, close air support (CAS) is defined as air action such as air strikes by fixed or rotary-winged aircraft against hostile targets near friendly forces and require detailed integration of each air mission with fire and movemen ...

.

Following the end of the Battle of Britain, Newall was quickly forced into retirement and replaced as Chief of the Air Staff by Charles Portal

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Charles Frederick Algernon Portal, 1st Viscount Portal of Hungerford, (21 May 1893 – 22 April 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer. He served as a bomber pilot in the First World War, and rose to become fi ...

. Contemporaries attributed this to the effects of overwork, which had certainly taken its toll, but there were also other aspects; Newall had lost political support, particularly following a dispute with Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

over the control of aircraft production and repair. Matters came to a head with the circulation of an anonymous memo attacking Newall, among other senior officers, as "a real weakness to the RAF and to the nation's defences". The author was Air Commodore Edgar McCloughry

Air Vice-Marshal Edgar James Kingston-McCloughry, (10 September 1896 – 15 November 1972), born Edgar James McCloughry, was an Australian fighter pilot and flying ace of the First World War, and a senior commander in the Royal Air Force during t ...

, a disaffected staff officer who saw himself as passed over for promotion and who had been brought into Beaverbrook's inner circle. Beaverbrook pressed Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

to dismiss Newall, gaining the support of influential ex-RAF figures such as Trenchard and Salmond. Trenchard had come out against Newall for his failure to launch a decisive strategic bombing offensive, while Salmond saw Newall's removal as the simplest way to replace Dowding as head of Fighter Command – despite Newall having also sought to sack Dowding.

He was promoted to Marshal of the Royal Air Force on 4 October 1940 and retired from the RAF later that month. He was awarded the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by ...

on 29 October, and made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

on 21 November.

New Zealand and later life

In February 1941 Newall was appointed

In February 1941 Newall was appointed Governor-General of New Zealand

The governor-general of New Zealand ( mi, te kāwana tianara o Aotearoa) is the Viceroy, viceregal representative of the Monarchy of New Zealand, monarch of New Zealand, currently King Charles III. As the King is concurrently the monarch of 14 ...

, a post he would hold for the remainder of the war. His time there was mostly quiet – described by one biographer as "a nice long rest" – and he toured the country extensively, referring to the war "in every public address".McLean (2006), p. 239 Newall and his wife, who also carried out an extensive program of engagements, were broadly popular, but there were occasional tensions; shortly after his arrival, it was widely (but mistakenly) rumoured that he had slighted the "men" of the Army in favour of the "gentlemen" of the RNZAF in a speech. A Freemason, Newall became Grand Master of New Zealand's Grand Lodge

A Grand Lodge (or Grand Orient or other similar title) is the overarching governing body of a fraternal or other similarly organized group in a given area, usually a city, state, or country.

In Freemasonry

A Grand Lodge or Grand Orient is the us ...

while Governor-General.

Politically, he had a lukewarm relationship with the Prime Minister, Peter Fraser – "I can't persuade myself that he is all he quite appears to be",McLean (2006), p. 245 Newall noted in a private report – but the two worked together effectively. Small problems occasionally flared up, such as that in October 1942, when Fraser was reprimanded for not personally informing Newall of the resignation of four ministers. However, only one developed into a direct confrontation, when Newall became the last Governor-General to refuse to follow the advice of his cabinet. Newall was presented with a government recommendation to remit four prisoners sentenced to be flogged, but refused to do so. He argued that if the government was opposed to flogging, it should repeal the legislation rather than maintain a policy of always remitting the sentences. This would be constitutionally improper, as it meant that the executive was overriding the legislature, which had provided for the sentence, and the judiciary, which had given it. Fraser, and his deputy Walter Nash

Sir Walter Nash (12 February 1882 – 4 June 1968) was a New Zealand politician who served as the 27th prime minister of New Zealand in the Second Labour Government from 1957 to 1960. He is noted for his long period of political service, hav ...

, refused to accept this response, and the impasse stretched out for several days; in the end, a compromise was reached where Newall remitted the sentences but the government undertook to repeal the legislation. The repeal bill was then extended to cover capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that ...

as well; the government had the same policy to always remit, and it was felt that both had to be handled in the same way.

A second conflict emerged just before the end of his term, when in 1945, the Labour government sought to abolish the country quota

The country quota was a part of the New Zealand electoral system from 1881 until 1945, when it was abolished by the First Labour Government. Its effect was to make urbanUrban electorate were those that contained cities or boroughs of over 2000 pe ...

, a system that gave additional electoral seats in rural areas. Farming groups – predominantly National-supporting – strongly opposed the move, and argued that such a major change could only be made after gaining approval in a general election. Newall sympathised, and advised Fraser to wait until after the election, but did not feel it was appropriate to intervene; he assented to the bill.

Following his return from New Zealand in 1946, Newall was raised to the peerage as Baron Newall, of Clifton upon Dunsmoor, in the county of Warwick. He spoke in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

rarely, making five speeches between 1946 and 1948 and one in 1959, mostly addressing defence issues. Newall died at his home at Welbeck Street in London on 30 November 1963, at which time his son Francis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

* Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Francis (surname)

Places

*Rural ...

inherited his title.

Arms

References

Sources

* * * * * * * , - , - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Newall, Cyril, 1st Baron 1886 births People educated at Bedford School Graduates of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst Royal Warwickshire Fusiliers officers Royal Air Force generals of World War I Royal Air Force air marshals of World War II Chiefs of the Air Staff (United Kingdom) Marshals of the Royal Air Force World War II political leaders Governors-General of New Zealand Members of the Order of Merit Commanders of the Order of the British Empire Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Knights of the Order of St John Recipients of the Albert Medal (lifesaving) Officiers of the Légion d'honneur Recipients of the Croix de guerre (Belgium) 1963 deaths Military personnel of British India British Indian Army officers New Zealand Freemasons Freemasons of the United Grand Lodge of England Barons created by George VI