Cymbeline on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Cymbeline'' , also known as ''The Tragedie of Cymbeline'' or ''Cymbeline, King of Britain'', is a play by

''Cymbeline'' , also known as ''The Tragedie of Cymbeline'' or ''Cymbeline, King of Britain'', is a play by _

Romance_(from_Vulgar_Latin_,_"in_the_Roman_language",_i.e.,_"Latin")_may_refer_to:

_Common_meanings

*_Romance_(love),_emotional_attraction_towards_another_person_and_the_courtship_behaviors_undertaken_to_express_the_feelings

*_Romance_languages,__...

_or_even_a_Shakespearean_comedy.html" "title="Shakespeare's_late_romances.html" "title="First_Folio.html" ;"title="ymbeline/nowiki>_(d._''c'' ...

. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio">ymbeline/nowiki>_(d._''c'' ... ''Cymbeline'' , also known as ''The Tragedie of Cymbeline'' or ''Cymbeline, King of Britain'', is a play by

''Cymbeline'' , also known as ''The Tragedie of Cymbeline'' or ''Cymbeline, King of Britain'', is a play by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

set in Ancient Britain

Several species of humans have intermittently occupied Great Britain for almost a million years. The earliest evidence of human occupation around 900,000 years ago is at Happisburgh on the Norfolk coast, with stone tools and footprints prob ...

() and based on legends that formed part of the Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the list of legendary kings of Britain, legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It ...

concerning the early Celtic British King Cunobeline

Cunobeline (or Cunobelin, from Latin , derived from Common Brittonic ''*Cunobelinos'' "Strong as a Dog", "Strong Dog") was a king in pre-Roman Britain from about AD 9 until about AD 40.Malcolm Todd (2004)"Cunobelinus_ ymbeline/nowiki>_(d._''c''_...

._Although_it_is_listed_as_a_tragedy_in_the_First_Folio,_modern_critics_often_classify_''Cymbeline''_as_a_._Although_it_is_listed_as_a_tragedy_in_the_First_Folio,_modern_critics_often_classify_''Cymbeline''_as_a_Shakespeare's_late_romances">romance. Although it is listed as a tragedy in the First Folio, modern critics often classify ''Cymbeline'' as a Shakespeare's late romances">romance Romance (from Vulgar Latin , "in the Roman language", i.e., "Latin") may refer to: Common meanings * Romance (love), emotional attraction towards another person and the courtship behaviors undertaken to express the feelings * Romance languages, ...

or even a Shakespearean comedy">comedy Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term o ...

. Like ''Othello'' and ''The Winter's Tale'', it deals with the themes of innocence and jealousy. While the precise date of composition remains unknown, the play was certainly produced as early as 1611.

Characters

;In Britain * Cymbeline – Modelled on the historical King of Britain,Cunobeline

Cunobeline (or Cunobelin, from Latin , derived from Common Brittonic ''*Cunobelinos'' "Strong as a Dog", "Strong Dog") was a king in pre-Roman Britain from about AD 9 until about AD 40.Malcolm Todd (2004)"Cunobelinus_ Imogen/Innogen – Cymbeline's daughter by a former queen, later disguised as the page Fidele

* Posthumus Leonatus – Innogen's husband, adopted as an orphan and raised in Cymbeline's family

* Cloten – Queen's son by a former husband and step-brother to Imogen

* Belarius – banished lord living under the name Morgan, who abducted King Cymbeline's infant sons in retaliation for his banishment

* Guiderius – Cymbeline's son, kidnapped in childhood by Belarius and raised as his son Polydore

* Arvirargus – Cymbeline's son, kidnapped in childhood by Belarius and raised as his son Cadwal

* Pisanio – Posthumus's servant, loyal to both Posthumus and Imogen

* Cornelius – court physician

* Helen – lady attending Imogen

* Two Lords attending Cloten

* Two Gentlemen

* Two Captains

* Two Jailers

;In Rome

* Philario – Posthumus's host in Rome

* Iachimo/Giacomo – a Roman lord and friend of Philario

* French Gentleman

* Dutch Gentleman

* Spanish Gentleman

* Caius Lucius – Roman ambassador and later general

* Two

Cymbeline, the

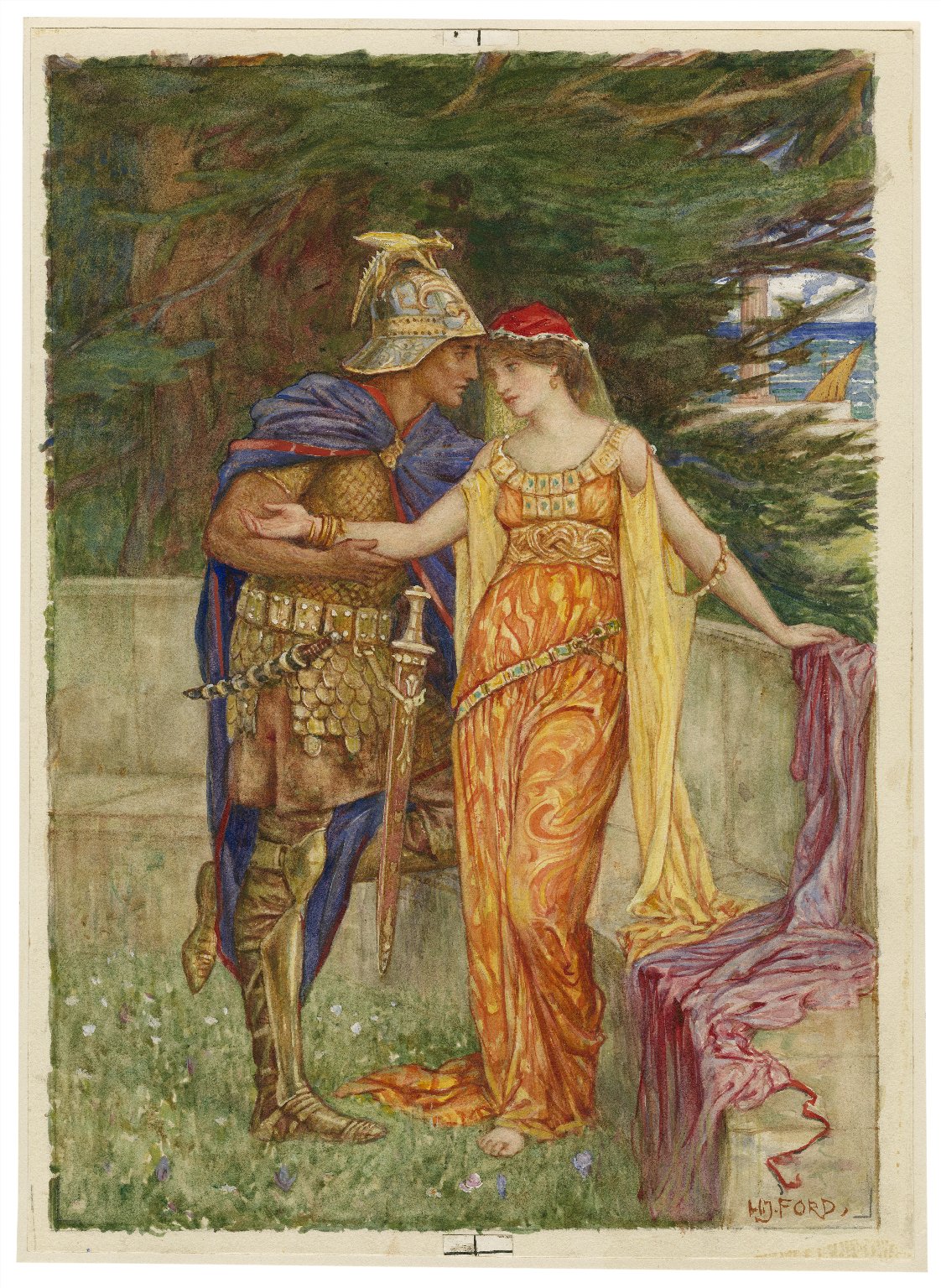

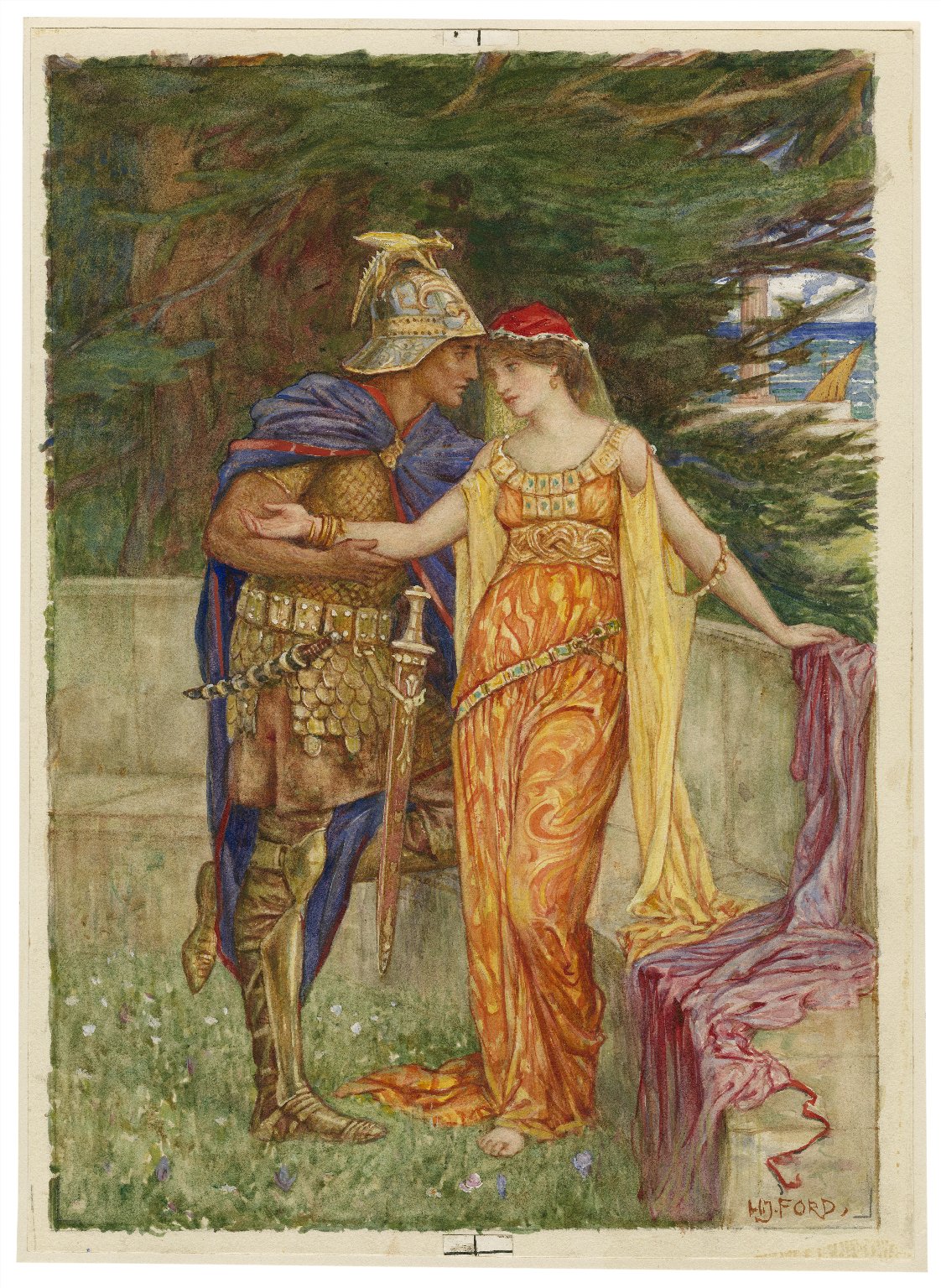

Cymbeline, the  Posthumus must now live in Italy, where he meets Iachimo (or Giacomo), who challenges the prideful Posthumus to a bet that he, Iachimo, can seduce Imogen, whom Posthumus has praised for her chastity, and then bring Posthumus proof of Imogen's adultery. If Iachimo wins, he will get Posthumus's token ring. If Posthumus wins, not only must Iachimo pay him but also fight Posthumus in a duel with swords. Iachimo heads to Britain where he aggressively attempts to seduce the faithful Imogen, who sends him packing. Iachimo then hides in a chest in Imogen's bedchamber and, when the princess falls asleep, emerges to steal Posthumus's bracelet from her. He also takes note of the room, as well as the mole on Imogen's partly naked body, to be able to present false evidence to Posthumus that he has seduced his bride. Returning to Italy, Iachimo convinces Posthumus that he has successfully seduced Imogen. In his wrath, Posthumus sends two letters to Britain: one to Imogen, telling her to meet him at

Posthumus must now live in Italy, where he meets Iachimo (or Giacomo), who challenges the prideful Posthumus to a bet that he, Iachimo, can seduce Imogen, whom Posthumus has praised for her chastity, and then bring Posthumus proof of Imogen's adultery. If Iachimo wins, he will get Posthumus's token ring. If Posthumus wins, not only must Iachimo pay him but also fight Posthumus in a duel with swords. Iachimo heads to Britain where he aggressively attempts to seduce the faithful Imogen, who sends him packing. Iachimo then hides in a chest in Imogen's bedchamber and, when the princess falls asleep, emerges to steal Posthumus's bracelet from her. He also takes note of the room, as well as the mole on Imogen's partly naked body, to be able to present false evidence to Posthumus that he has seduced his bride. Returning to Italy, Iachimo convinces Posthumus that he has successfully seduced Imogen. In his wrath, Posthumus sends two letters to Britain: one to Imogen, telling her to meet him at  Back at Cymbeline's court, Cymbeline refuses to pay his British tribute to the Roman ambassador Caius Lucius, and Lucius warns Cymbeline of the Roman Emperor's forthcoming wrath, which will amount to an invasion of Britain by Roman troops. Meanwhile, Cloten learns of the "meeting" between Imogen and Posthumus at Milford Haven. Dressing himself enviously in Posthumus's clothes, he decides to go to Wales to kill Posthumus, and then rape, abduct, and marry Imogen. Imogen has now been travelling as Fidele through the Welsh mountains, her health in decline as she comes to a cave: the home of Belarius, along with his "sons" Polydore and Cadwal, whom he raised into great hunters. These two young men are in fact the British princes Guiderius and Arviragus, who themselves do not realise their own origin. The men discover Fidele, and, instantly captivated by a strange affinity for "him", become fast friends. Outside the cave, Guiderius is met by Cloten, who throws insults, leading to a sword fight during which Guiderius beheads Cloten. Meanwhile, Imogen's fragile state worsens and she takes the "poison" as a hopeful medicine; when the men re-enter, they find her "dead." They mourn and, after placing Cloten's body beside hers, briefly depart to prepare for the double burial. Imogen awakes to find the headless body, and believes it to be Posthumus because the body is wearing Posthumus's clothes. Lucius' Roman soldiers have just arrived in Britain and, as the army moves through Wales, Lucius discovers the devastated Fidele, who pretends to be a loyal servant grieving for his killed master; Lucius, moved by this faithfulness, enlists Fidele as a pageboy.

The treacherous Queen is now wasting away due to the disappearance of her son Cloten. Meanwhile, despairing of his life, the guilt-ridden Posthumus enlists in the Roman forces as they begin their invasion of Britain. Belarius, Guiderius, Arviragus, and Posthumus all help rescue Cymbeline from the Roman onslaught; the king does not yet recognise these four, yet takes notice of them as they go on to fight bravely and even capture the Roman commanders, Lucius and Iachimo, thus winning the day. Posthumus, allowing himself to be captured, as well as Fidele, are imprisoned alongside the true Romans, all of whom await execution. In jail, Posthumus sleeps, while the ghosts of his dead family appear to complain to

Back at Cymbeline's court, Cymbeline refuses to pay his British tribute to the Roman ambassador Caius Lucius, and Lucius warns Cymbeline of the Roman Emperor's forthcoming wrath, which will amount to an invasion of Britain by Roman troops. Meanwhile, Cloten learns of the "meeting" between Imogen and Posthumus at Milford Haven. Dressing himself enviously in Posthumus's clothes, he decides to go to Wales to kill Posthumus, and then rape, abduct, and marry Imogen. Imogen has now been travelling as Fidele through the Welsh mountains, her health in decline as she comes to a cave: the home of Belarius, along with his "sons" Polydore and Cadwal, whom he raised into great hunters. These two young men are in fact the British princes Guiderius and Arviragus, who themselves do not realise their own origin. The men discover Fidele, and, instantly captivated by a strange affinity for "him", become fast friends. Outside the cave, Guiderius is met by Cloten, who throws insults, leading to a sword fight during which Guiderius beheads Cloten. Meanwhile, Imogen's fragile state worsens and she takes the "poison" as a hopeful medicine; when the men re-enter, they find her "dead." They mourn and, after placing Cloten's body beside hers, briefly depart to prepare for the double burial. Imogen awakes to find the headless body, and believes it to be Posthumus because the body is wearing Posthumus's clothes. Lucius' Roman soldiers have just arrived in Britain and, as the army moves through Wales, Lucius discovers the devastated Fidele, who pretends to be a loyal servant grieving for his killed master; Lucius, moved by this faithfulness, enlists Fidele as a pageboy.

The treacherous Queen is now wasting away due to the disappearance of her son Cloten. Meanwhile, despairing of his life, the guilt-ridden Posthumus enlists in the Roman forces as they begin their invasion of Britain. Belarius, Guiderius, Arviragus, and Posthumus all help rescue Cymbeline from the Roman onslaught; the king does not yet recognise these four, yet takes notice of them as they go on to fight bravely and even capture the Roman commanders, Lucius and Iachimo, thus winning the day. Posthumus, allowing himself to be captured, as well as Fidele, are imprisoned alongside the true Romans, all of whom await execution. In jail, Posthumus sleeps, while the ghosts of his dead family appear to complain to  Cornelius arrives in the court to announce that the Queen has died suddenly, and that on her deathbed she unrepentantly confessed to villainous schemes against her husband and his throne. Both troubled and relieved at this news, Cymbeline prepares to execute his new prisoners, but pauses when he sees Fidele, whom he finds both beautiful and somehow familiar. Fidele has noticed Posthumus's ring on Iachimo's finger and abruptly demands to know from where the jewel came. A remorseful Iachimo tells of his bet, and how he could not seduce Imogen, yet tricked Posthumus into thinking he had. Posthumus then comes forward to confirm Iachimo's story, revealing his identity and acknowledging his wrongfulness in desiring Imogen killed. Ecstatic, Imogen throws herself at Posthumus, who still takes her for a boy and knocks her down. Pisanio then rushes forward to explain that Fidele is Imogen in disguise; Imogen still suspects that Pisanio conspired with the Queen to give her the poison. Pisanio sincerely claims innocence, and Cornelius reveals how the poison was a non-fatal potion all along. Insisting that his betrayal years ago was a set-up, Belarius makes his own happy confession, revealing Guiderius and Arviragus as Cymbeline's own two long-lost sons. With her brothers restored to their place in the line of inheritance, Imogen is now free to marry Posthumus. An elated Cymbeline pardons Belarius and the Roman prisoners, including Lucius and Iachimo. Lucius calls forth his soothsayer to decipher a prophecy of recent events, which ensures happiness for all. Blaming his manipulative Queen for his refusal to pay earlier, Cymbeline now agrees to pay the tribute to the Roman Emperor as a gesture of peace between Britain and Rome, and he invites everyone to a great feast.

Cornelius arrives in the court to announce that the Queen has died suddenly, and that on her deathbed she unrepentantly confessed to villainous schemes against her husband and his throne. Both troubled and relieved at this news, Cymbeline prepares to execute his new prisoners, but pauses when he sees Fidele, whom he finds both beautiful and somehow familiar. Fidele has noticed Posthumus's ring on Iachimo's finger and abruptly demands to know from where the jewel came. A remorseful Iachimo tells of his bet, and how he could not seduce Imogen, yet tricked Posthumus into thinking he had. Posthumus then comes forward to confirm Iachimo's story, revealing his identity and acknowledging his wrongfulness in desiring Imogen killed. Ecstatic, Imogen throws herself at Posthumus, who still takes her for a boy and knocks her down. Pisanio then rushes forward to explain that Fidele is Imogen in disguise; Imogen still suspects that Pisanio conspired with the Queen to give her the poison. Pisanio sincerely claims innocence, and Cornelius reveals how the poison was a non-fatal potion all along. Insisting that his betrayal years ago was a set-up, Belarius makes his own happy confession, revealing Guiderius and Arviragus as Cymbeline's own two long-lost sons. With her brothers restored to their place in the line of inheritance, Imogen is now free to marry Posthumus. An elated Cymbeline pardons Belarius and the Roman prisoners, including Lucius and Iachimo. Lucius calls forth his soothsayer to decipher a prophecy of recent events, which ensures happiness for all. Blaming his manipulative Queen for his refusal to pay earlier, Cymbeline now agrees to pay the tribute to the Roman Emperor as a gesture of peace between Britain and Rome, and he invites everyone to a great feast.

''Cymbeline: Second Series''

p.xxiv quote: and Pisanio's reluctance to kill Imogen and his use of her bloody clothes to convince Posthumus of her death derive from ''Frederyke of Jennen.'' In both sources, the equivalent to Posthumus's bracelet is stolen jewellery that the wife later recognises while cross-dressed. Shakespeare also drew inspiration for ''Cymbeline'' from a play called ''The Rare Triumphs of Love and Fortune,'' first performed in 1582. There are many parallels between the characters of the two plays, including a king's daughter who falls for a man of unknown birth who grew up in the king's court. The subplot of Belarius and the lost princes was inspired by the story of Bomelio, an exiled nobleman in ''The Rare Triumphs'' who is later revealed to be the protagonist's father.

The editors of the Oxford and Norton Shakespeare believe the name of Imogen is a misprint for Innogen—they draw several comparisons between ''Cymbeline'' and ''

The editors of the Oxford and Norton Shakespeare believe the name of Imogen is a misprint for Innogen—they draw several comparisons between ''Cymbeline'' and ''

The play entered the Romantic era with

The play entered the Romantic era with

The play was adapted by

The play was adapted by

broadcast productions of ''Cymbeline'' in the Roman senators

The Roman Senate ( la, Senātus Rōmānus) was a governing and advisory assembly in ancient Rome. It was one of the most enduring institutions in Roman history, being established in the first days of the city of Rome (traditionally founded in ...

* Roman tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the ...

s

* Roman captain

* Philharmonus – soothsayer

;Apparitions

* Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

– King of the gods in Roman mythology

Roman mythology is the body of myths of ancient Rome as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans. One of a wide variety of genres of Roman folklore, ''Roman mythology'' may also refer to the modern study of these representat ...

* Sicilius Leonatus – Posthumus's father

* Posthumus's mother

* Posthumus's two brothers

Summary

Cymbeline, the

Cymbeline, the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

's vassal king of Britain, once had two sons, Guiderius and Arvirargus, but they were stolen 20 years earlier as infants by an exiled traitor named Belarius. Cymbeline discovers that his only child left, his daughter Imogen (or Innogen), has secretly married her lover Posthumus Leonatus, a member of Cymbeline's court. The lovers have exchanged jewellery as tokens: Imogen with a bracelet, and Posthumus with a ring. Cymbeline dismisses the marriage and banishes Posthumus since Imogen — as Cymbeline's only child — must produce a fully royal-blooded heir to succeed to the British throne. In the meantime, Cymbeline's Queen is conspiring to have Cloten (her cloddish and arrogant son by an earlier marriage) married to Imogen to secure her bloodline. The Queen is also plotting to murder both Imogen and Cymbeline, procuring what she believes to be deadly poison from the court doctor. The doctor, Cornelius, is suspicious and switches the poison for a harmless sleeping potion. The Queen passes the "poison" along to Pisanio, Posthumus and Imogen's loving servant — the latter is led to believe it is a medicinal drug. No longer able to be with her banished Posthumus, Imogen secludes herself in her chambers, away from Cloten's aggressive advances.

Posthumus must now live in Italy, where he meets Iachimo (or Giacomo), who challenges the prideful Posthumus to a bet that he, Iachimo, can seduce Imogen, whom Posthumus has praised for her chastity, and then bring Posthumus proof of Imogen's adultery. If Iachimo wins, he will get Posthumus's token ring. If Posthumus wins, not only must Iachimo pay him but also fight Posthumus in a duel with swords. Iachimo heads to Britain where he aggressively attempts to seduce the faithful Imogen, who sends him packing. Iachimo then hides in a chest in Imogen's bedchamber and, when the princess falls asleep, emerges to steal Posthumus's bracelet from her. He also takes note of the room, as well as the mole on Imogen's partly naked body, to be able to present false evidence to Posthumus that he has seduced his bride. Returning to Italy, Iachimo convinces Posthumus that he has successfully seduced Imogen. In his wrath, Posthumus sends two letters to Britain: one to Imogen, telling her to meet him at

Posthumus must now live in Italy, where he meets Iachimo (or Giacomo), who challenges the prideful Posthumus to a bet that he, Iachimo, can seduce Imogen, whom Posthumus has praised for her chastity, and then bring Posthumus proof of Imogen's adultery. If Iachimo wins, he will get Posthumus's token ring. If Posthumus wins, not only must Iachimo pay him but also fight Posthumus in a duel with swords. Iachimo heads to Britain where he aggressively attempts to seduce the faithful Imogen, who sends him packing. Iachimo then hides in a chest in Imogen's bedchamber and, when the princess falls asleep, emerges to steal Posthumus's bracelet from her. He also takes note of the room, as well as the mole on Imogen's partly naked body, to be able to present false evidence to Posthumus that he has seduced his bride. Returning to Italy, Iachimo convinces Posthumus that he has successfully seduced Imogen. In his wrath, Posthumus sends two letters to Britain: one to Imogen, telling her to meet him at Milford Haven

Milford Haven ( cy, Aberdaugleddau, meaning "mouth of the two Rivers Cleddau") is both a town and a community in Pembrokeshire, Wales. It is situated on the north side of the Milford Haven Waterway, an estuary forming a natural harbour that has ...

, on the Welsh coast; the other to the servant Pisanio, ordering him to murder Imogen at the Haven. However, Pisanio refuses to kill Imogen and reveals to her Posthumus's plot. He has Imogen disguise herself as a boy and continue to Milford Haven to seek employment. He also gives her the Queen's "poison", believing it will alleviate her psychological distress. In the guise of a boy, Imogen adopts the name "Fidele", meaning "faithful".

Back at Cymbeline's court, Cymbeline refuses to pay his British tribute to the Roman ambassador Caius Lucius, and Lucius warns Cymbeline of the Roman Emperor's forthcoming wrath, which will amount to an invasion of Britain by Roman troops. Meanwhile, Cloten learns of the "meeting" between Imogen and Posthumus at Milford Haven. Dressing himself enviously in Posthumus's clothes, he decides to go to Wales to kill Posthumus, and then rape, abduct, and marry Imogen. Imogen has now been travelling as Fidele through the Welsh mountains, her health in decline as she comes to a cave: the home of Belarius, along with his "sons" Polydore and Cadwal, whom he raised into great hunters. These two young men are in fact the British princes Guiderius and Arviragus, who themselves do not realise their own origin. The men discover Fidele, and, instantly captivated by a strange affinity for "him", become fast friends. Outside the cave, Guiderius is met by Cloten, who throws insults, leading to a sword fight during which Guiderius beheads Cloten. Meanwhile, Imogen's fragile state worsens and she takes the "poison" as a hopeful medicine; when the men re-enter, they find her "dead." They mourn and, after placing Cloten's body beside hers, briefly depart to prepare for the double burial. Imogen awakes to find the headless body, and believes it to be Posthumus because the body is wearing Posthumus's clothes. Lucius' Roman soldiers have just arrived in Britain and, as the army moves through Wales, Lucius discovers the devastated Fidele, who pretends to be a loyal servant grieving for his killed master; Lucius, moved by this faithfulness, enlists Fidele as a pageboy.

The treacherous Queen is now wasting away due to the disappearance of her son Cloten. Meanwhile, despairing of his life, the guilt-ridden Posthumus enlists in the Roman forces as they begin their invasion of Britain. Belarius, Guiderius, Arviragus, and Posthumus all help rescue Cymbeline from the Roman onslaught; the king does not yet recognise these four, yet takes notice of them as they go on to fight bravely and even capture the Roman commanders, Lucius and Iachimo, thus winning the day. Posthumus, allowing himself to be captured, as well as Fidele, are imprisoned alongside the true Romans, all of whom await execution. In jail, Posthumus sleeps, while the ghosts of his dead family appear to complain to

Back at Cymbeline's court, Cymbeline refuses to pay his British tribute to the Roman ambassador Caius Lucius, and Lucius warns Cymbeline of the Roman Emperor's forthcoming wrath, which will amount to an invasion of Britain by Roman troops. Meanwhile, Cloten learns of the "meeting" between Imogen and Posthumus at Milford Haven. Dressing himself enviously in Posthumus's clothes, he decides to go to Wales to kill Posthumus, and then rape, abduct, and marry Imogen. Imogen has now been travelling as Fidele through the Welsh mountains, her health in decline as she comes to a cave: the home of Belarius, along with his "sons" Polydore and Cadwal, whom he raised into great hunters. These two young men are in fact the British princes Guiderius and Arviragus, who themselves do not realise their own origin. The men discover Fidele, and, instantly captivated by a strange affinity for "him", become fast friends. Outside the cave, Guiderius is met by Cloten, who throws insults, leading to a sword fight during which Guiderius beheads Cloten. Meanwhile, Imogen's fragile state worsens and she takes the "poison" as a hopeful medicine; when the men re-enter, they find her "dead." They mourn and, after placing Cloten's body beside hers, briefly depart to prepare for the double burial. Imogen awakes to find the headless body, and believes it to be Posthumus because the body is wearing Posthumus's clothes. Lucius' Roman soldiers have just arrived in Britain and, as the army moves through Wales, Lucius discovers the devastated Fidele, who pretends to be a loyal servant grieving for his killed master; Lucius, moved by this faithfulness, enlists Fidele as a pageboy.

The treacherous Queen is now wasting away due to the disappearance of her son Cloten. Meanwhile, despairing of his life, the guilt-ridden Posthumus enlists in the Roman forces as they begin their invasion of Britain. Belarius, Guiderius, Arviragus, and Posthumus all help rescue Cymbeline from the Roman onslaught; the king does not yet recognise these four, yet takes notice of them as they go on to fight bravely and even capture the Roman commanders, Lucius and Iachimo, thus winning the day. Posthumus, allowing himself to be captured, as well as Fidele, are imprisoned alongside the true Romans, all of whom await execution. In jail, Posthumus sleeps, while the ghosts of his dead family appear to complain to Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

of his grim fate. Jupiter himself then appears in thunder and glory to assure the others that destiny will grant happiness to Posthumus and Britain.

Cornelius arrives in the court to announce that the Queen has died suddenly, and that on her deathbed she unrepentantly confessed to villainous schemes against her husband and his throne. Both troubled and relieved at this news, Cymbeline prepares to execute his new prisoners, but pauses when he sees Fidele, whom he finds both beautiful and somehow familiar. Fidele has noticed Posthumus's ring on Iachimo's finger and abruptly demands to know from where the jewel came. A remorseful Iachimo tells of his bet, and how he could not seduce Imogen, yet tricked Posthumus into thinking he had. Posthumus then comes forward to confirm Iachimo's story, revealing his identity and acknowledging his wrongfulness in desiring Imogen killed. Ecstatic, Imogen throws herself at Posthumus, who still takes her for a boy and knocks her down. Pisanio then rushes forward to explain that Fidele is Imogen in disguise; Imogen still suspects that Pisanio conspired with the Queen to give her the poison. Pisanio sincerely claims innocence, and Cornelius reveals how the poison was a non-fatal potion all along. Insisting that his betrayal years ago was a set-up, Belarius makes his own happy confession, revealing Guiderius and Arviragus as Cymbeline's own two long-lost sons. With her brothers restored to their place in the line of inheritance, Imogen is now free to marry Posthumus. An elated Cymbeline pardons Belarius and the Roman prisoners, including Lucius and Iachimo. Lucius calls forth his soothsayer to decipher a prophecy of recent events, which ensures happiness for all. Blaming his manipulative Queen for his refusal to pay earlier, Cymbeline now agrees to pay the tribute to the Roman Emperor as a gesture of peace between Britain and Rome, and he invites everyone to a great feast.

Cornelius arrives in the court to announce that the Queen has died suddenly, and that on her deathbed she unrepentantly confessed to villainous schemes against her husband and his throne. Both troubled and relieved at this news, Cymbeline prepares to execute his new prisoners, but pauses when he sees Fidele, whom he finds both beautiful and somehow familiar. Fidele has noticed Posthumus's ring on Iachimo's finger and abruptly demands to know from where the jewel came. A remorseful Iachimo tells of his bet, and how he could not seduce Imogen, yet tricked Posthumus into thinking he had. Posthumus then comes forward to confirm Iachimo's story, revealing his identity and acknowledging his wrongfulness in desiring Imogen killed. Ecstatic, Imogen throws herself at Posthumus, who still takes her for a boy and knocks her down. Pisanio then rushes forward to explain that Fidele is Imogen in disguise; Imogen still suspects that Pisanio conspired with the Queen to give her the poison. Pisanio sincerely claims innocence, and Cornelius reveals how the poison was a non-fatal potion all along. Insisting that his betrayal years ago was a set-up, Belarius makes his own happy confession, revealing Guiderius and Arviragus as Cymbeline's own two long-lost sons. With her brothers restored to their place in the line of inheritance, Imogen is now free to marry Posthumus. An elated Cymbeline pardons Belarius and the Roman prisoners, including Lucius and Iachimo. Lucius calls forth his soothsayer to decipher a prophecy of recent events, which ensures happiness for all. Blaming his manipulative Queen for his refusal to pay earlier, Cymbeline now agrees to pay the tribute to the Roman Emperor as a gesture of peace between Britain and Rome, and he invites everyone to a great feast.

Sources

''Cymbeline'' is grounded in the story of the historical British kingCunobeline

Cunobeline (or Cunobelin, from Latin , derived from Common Brittonic ''*Cunobelinos'' "Strong as a Dog", "Strong Dog") was a king in pre-Roman Britain from about AD 9 until about AD 40.Malcolm Todd (2004)"Cunobelinus_ ymbeline/nowiki>_(d._''c'' ...

, which was originally recorded in Geoffrey of Monmouth's ''Historia Regum Britanniae'', but which Shakespeare likely found in the 1587 edition of Raphael ''Holinshed's Chronicles''. Shakespeare based the setting of the play and the character Cymbeline on what he found in Holinshed's chronicles, but the plot and subplots of the play are derived from other sources. The subplot of Posthumus and Iachimo's wager derives from story II.9 of Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was somet ...

's ''The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label=Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Dan ...

'' and the anonymously authored ''Frederyke of Jennen''. These share similar characters and wager terms, and both feature Iachimo's equivalent hiding in a chest in order to gather proof in Imogen's room. Iachimo's description of Imogen's room as proof of her infidelity derives from ''The Decameron'',Nosworthy, J. M. (1955) ''Preface'' i''Cymbeline: Second Series''

p.xxiv quote: and Pisanio's reluctance to kill Imogen and his use of her bloody clothes to convince Posthumus of her death derive from ''Frederyke of Jennen.'' In both sources, the equivalent to Posthumus's bracelet is stolen jewellery that the wife later recognises while cross-dressed. Shakespeare also drew inspiration for ''Cymbeline'' from a play called ''The Rare Triumphs of Love and Fortune,'' first performed in 1582. There are many parallels between the characters of the two plays, including a king's daughter who falls for a man of unknown birth who grew up in the king's court. The subplot of Belarius and the lost princes was inspired by the story of Bomelio, an exiled nobleman in ''The Rare Triumphs'' who is later revealed to be the protagonist's father.

Date and text

The first recorded production of ''Cymbeline'', as noted bySimon Forman

Simon Forman (31 December 1552 – 5 or 12 September 1611) was an Elizabethan astrologer, occultist and herbalist active in London during the reigns of Queen Elizabeth I and James I of England. His reputation, however, was severely tarnishe ...

, was in April 1611. It was first published in the ''First Folio

''Mr. William Shakespeare's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies'' is a collection of plays by William Shakespeare, commonly referred to by modern scholars as the First Folio, published in 1623, about seven years after Shakespeare's death. It is cons ...

'' in 1623. When ''Cymbeline'' was actually written cannot be precisely dated.

The Yale edition suggests a collaborator had a hand in the authorship, and some scenes (e.g., Act III scene 7 and Act V scene 2) may strike the reader as particularly un-Shakespearean when compared with others. The play shares notable similarities in language, situation, and plot with Beaumont and Fletcher

Beaumont and Fletcher were the English dramatists Francis Beaumont and John Fletcher, who collaborated in their writing during the reign of James I (1603–25).

They became known as a team early in their association, so much so that their jo ...

's tragicomedy '' Philaster, or Love Lies a-Bleeding'' (). Both plays concern themselves with a princess who, after disobeying her father in order to marry a lowly lover, is wrongly accused of infidelity and thus ordered to be murdered, before escaping and having her faithfulness proven. Furthermore, both were written for the same theatre company and audience. Some scholars believe this supports a dating of approximately 1609, though it is not clear which play preceded the other. The editors of the Oxford and Norton Shakespeare believe the name of Imogen is a misprint for Innogen—they draw several comparisons between ''Cymbeline'' and ''

The editors of the Oxford and Norton Shakespeare believe the name of Imogen is a misprint for Innogen—they draw several comparisons between ''Cymbeline'' and ''Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' ( W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. 1387 The play ...

'', in early editions of which a ghost character

A ghost character, in the bibliographic or scholarly study of texts of dramatic literature, is a term for an inadvertent error committed by the playwright in the act of writing. It is a character who is mentioned as appearing on stage, but who doe ...

named Innogen was supposed to be Leonato's wife (Posthumus being also known as "Leonatus", the Latin form of the Italian name in the other play). Stanley Wells

Sir Stanley William Wells, (born 21 May 1930) is a Shakespearean scholar, writer, professor and editor who has been honorary president of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, professor emeritus at Birmingham University, and author of many books a ...

and Michael Dobson point out that Holinshed's ''Chronicles'', which Shakespeare used as a source, mention an Innogen and that Forman's eyewitness account of the April 1611 performance refers to "Innogen" throughout. In spite of these arguments, most editions of the play have continued to use the name Imogen.

Milford Haven is not known to have been used during the period (early 1st century AD) in which ''Cymbeline'' is set, and it is not known why Shakespeare used it in the play. Robert Nye

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, hono ...

noted that it was the closest seaport to Shakespeare's home town of Stratford-upon-Avon

Stratford-upon-Avon (), commonly known as just Stratford, is a market town and civil parish in the Stratford-on-Avon district, in the county of Warwickshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It is situated on the River Avon, north-we ...

: "But if you marched due west from Stratford, looking neither to left nor to right, with the idea of running away to sea in your young head, then Milford Haven is the port you'd reach," a walk of about , about six days' journey, that the young Shakespeare might well have taken, or at least dreamed of taking. Marisa R. Cull Marisa may refer to:

* Marisa (town), an Indonesian town

* Marisa, Hellenised name of Maresha, town in Idumea (today in Israel)

* Marisa (given name), a feminine personal name

* ''Marisa'' (gastropod), a genus of apple snails

* MV ''Marisa'' (193 ...

notes its possible symbolism as the landing site of Henry Tudor, when he invaded England via Milford on 7 August 1485 on his way to deposing Richard III

Richard III (2 October 145222 August 1485) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 26 June 1483 until his death in 1485. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat and death at the Battl ...

and establishing the Tudor dynasty

The House of Tudor was a royal house of largely Welsh and English origin that held the English throne from 1485 to 1603. They descended from the Tudors of Penmynydd and Catherine of France. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and it ...

. It may also reflect English anxiety about the loyalty of the Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

and the possibility of future invasions at Milford.

Criticism and interpretation

''Cymbeline'' was one of Shakespeare's more popular plays during the eighteenth century, though critics includingSamuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

took issue with its complex plot:

William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt (10 April 177818 September 1830) was an English essayist, drama and literary critic, painter, social commentator, and philosopher. He is now considered one of the greatest critics and essayists in the history of the English lan ...

and John Keats

John Keats (31 October 1795 – 23 February 1821) was an English poet of the second generation of Romantic poets, with Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. His poems had been in publication for less than four years when he died of tuberculo ...

, however, numbered it among their favourite plays.

By the early twentieth century, the play had lost favour. Lytton Strachey

Giles Lytton Strachey (; 1 March 1880 – 21 January 1932) was an English writer and critic. A founding member of the Bloomsbury Group and author of ''Eminent Victorians'', he established a new form of biography in which psychological insight ...

found it "difficult to resist the conclusion that hakespearewas getting bored himself. Bored with people, bored with real life, bored with drama, bored, in fact, with everything except poetry and poetical dreams." Harley Granville-Barker

Harley Granville-Barker (25 November 1877 – 31 August 1946) was an English actor, director, playwright, manager, critic, and theorist. After early success as an actor in the plays of George Bernard Shaw, he increasingly turned to directi ...

had similar views, saying that the play shows that Shakespeare was becoming a "wearied artist".

Some have argued that the play parodies its own content. Harold Bloom

Harold Bloom (July 11, 1930 – October 14, 2019) was an American literary critic and the Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale University. In 2017, Bloom was described as "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking wor ...

says "Cymbeline, in my judgment, is partly a Shakespearean self-parody; many of his prior plays and characters are mocked by it."

British identity

Similarities between Cymbeline and historical accounts of theRoman Emperor Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

have prompted critics to interpret the play as Shakespeare voicing support for the political motions of James I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

, who considered himself the "British Augustus." His political manoeuvres to unite Scotland with England and Wales as an empire mirror Augustus' ''Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is periodization, identified as a period and as a golden age (metaphor), golden age of increased as well as sustained Imperial cult of ancient Rome ...

.'' The play reinforces the Jacobean idea that Britain is the successor to the civilised virtue of ancient Rome, portraying the parochialism and isolationism of Cloten and the Queen as villainous. Other critics have resisted the idea that ''Cymbeline'' endorses James I's ideas about national identity, pointing to several characters' conflicted constructions of their geographic identities. For example, although Guiderius and Arviragus are the sons of Cymbeline, a British king raised in Rome, they grew up in a Welsh cave. The brothers lament their isolation from society, a quality associated with barbarousness, but Belarius, their adoptive father, retorts that this has spared them from corrupting influences of the supposedly civilised British court.

Iachimo's invasion of Imogen's bedchamber reflects concern that Britain was being maligned by Italian influence. As noted by Peter A. Parolin, ''Cymbeline’s'' scenes ostensibly set in ancient Rome are in fact anachronistic portrayals of sixteenth-century Italy, which was characterised by contemporary British authors as a place where vice, debauchery, and treachery had supplanted the virtue of ancient Rome. Though ''Cymbeline'' concludes with a peace forged between Britain and Rome, Iachimo's corruption of Posthumus and metaphorical rape of Imogen demonstrate fears that Britain's political union with other cultures might expose Britons to harmful foreign influences.

Gender and sexuality

Scholars have emphasised that the play attributes great political significance to Imogen's virginity andchastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when mak ...

. There is some debate as to whether Imogen and Posthumus's marriage is legitimate. Imogen has historically been played and received as an ideal, chaste woman maintaining qualities applauded in a patriarchal

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of Dominance hierarchy, dominance and Social privilege, privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical Anthropology, anthropological term for families or clans controll ...

structure; however, critics argue that Imogen's actions contradict these social definitions through her defiance of her father and her cross-dressing. Yet critics including Tracey Miller-Tomlinson have emphasised the ways in which the play upholds patriarchal ideology, including in the final scene, with its panoply of male victors. Whilst Imogen and Posthumus's marriage at first upholds heterosexual

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to ...

norms, their separation and final reunion leave open non-heterosexual possibilities, initially exposed by Imogen's cross-dressing as Fidele. Miller-Tomlinson points out the falseness of their social significance as a "perfect example" of a public "heterosexual marriage", considering that their private relations turn out to be "homosocial, homoerotic

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

, and hermaphroditic."

Queer theory has gained traction in scholarship on ''Cymbeline'', building upon the work of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick (; May 2, 1950 – April 12, 2009) was an American academic scholar in the fields of gender studies, queer theory ( queer studies), and critical theory. Sedgwick published several books considered groundbreaking in the fiel ...

and Judith Butler

Judith Pamela Butler (born February 24, 1956) is an American philosopher and gender theorist whose work has influenced political philosophy, ethics, and the fields of third-wave feminism, queer theory, and literary theory. In 1993, Butler ...

. Scholarship on this topic has emphasised the play's Ovidian

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

allusions and exploration of non-normative gender/sexuality – achieved through separation from traditional society into what Valerie Traub terms "green worlds." Amongst the most obvious and frequently cited examples of this non-normative dimension of the play is the prominence of homoeroticism, as seen in Guiderius and Arviragus's semi-sexual fascination with the disguised Imogen/Fidele. In addition to homoerotic and homosocial elements, the subjects of hermaphroditism

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite () is an organism that has both kinds of reproductive organs and can produce both gametes associated with male and female sexes.

Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have separ ...

and paternity/maternity also feature prominently in queer interpretations of ''Cymbeline''. Janet Adelman set the tone for the intersection of paternity and hermaphroditism in arguing that Cymbeline's lines, "oh, what am I, / A mother to the birth of three? Ne’er mother / Rejoiced deliverance more", amount a "parthenogenesis fantasy".''Cymbeline'', V.v.32.''Cymbeline'', V. vi.369-71. According to Adelman and Tracey Miller-Tomlinson, in taking sole credit for the creation of his children Cymbeline acts a hermaphrodite who transforms a maternal function into a patriarchal strategy by regaining control of his male heirs and daughter, Imogen. Imogen's own experience with gender fluidity and cross-dressing

Cross-dressing is the act of wearing clothes usually worn by a different gender. From as early as pre-modern history, cross-dressing has been practiced in order to disguise, comfort, entertain, and self-express oneself.

Cross-dressing has play ...

has largely been interpreted through a patriarchal lens. Unlike other Shakespearean agents of onstage gender fluidity – Portia, Rosalind, Viola

The viola ( , also , ) is a string instrument that is bow (music), bowed, plucked, or played with varying techniques. Slightly larger than a violin, it has a lower and deeper sound. Since the 18th century, it has been the middle or alto voice of ...

and Julia

Julia is usually a feminine given name. It is a Latinate feminine form of the name Julio and Julius. (For further details on etymology, see the Wiktionary entry "Julius".) The given name ''Julia'' had been in use throughout Late Antiquity (e.g. ...

– Imogen is not afforded empowerment upon her transformation into Fidele. Instead, Imogen's power is inherited from her father and based upon the prospect of reproduction.

Performance history

After the 1611 performance mentioned by Simon Forman, there is no record of production until 1634, when the play was revived at court forCharles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria (french: link=no, Henriette Marie; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland from her marriage to King Charles I on 13 June 1625 until Charles was executed on 30 January 1649. She wa ...

. The Caroline production was noted as being "well likte by the kinge." In 1728 John Rich

John Rich (born January 7, 1974) is an American country music singer-songwriter. From 1992 to 1998, he was a member of the country music band Lonestar, in which he played bass guitar and alternated with Richie McDonald as lead vocalist. After d ...

staged the play with his company at Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in develo ...

, with emphasis placed on the spectacle of the production rather than the text of the play. Theophilus Cibber

Theophilus Cibber (25 or 26 November 1703 – October 1758) was an English actor, playwright, author, and son of the actor-manager Colley Cibber.

He began acting at an early age, and followed his father into theatrical management. In 1727, Alex ...

revived Shakespeare's text in 1744 with a performance at the Haymarket Haymarket may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Haymarket, New South Wales, area of Sydney, Australia

Germany

* Heumarkt (KVB), transport interchange in Cologne on the site of the Heumarkt (literally: hay market)

Russia

* Sennaya Square (''Hay Squ ...

. There is evidence that Cibber put on another performance in 1746, and another in 1758.

In 1761, David Garrick

David Garrick (19 February 1717 – 20 January 1779) was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of European theatrical practice throughout the 18th century, and was a pupil and friend of Sa ...

edited a new version of the text. It is recognized as being close to the original Shakespeare, although there are several differences. Changes included the shortening of Imogen's burial scene and the entire fifth act, including the removal of Posthumus's dream. Garrick's text was first performed in November of that year, starring Garrick himself as Posthumus. Several scholars have indicated that Garrick's Posthumus was much liked. Valerie Wayne notes that Garrick's changes made the play more nationalistic, representing a trend in perception of ''Cymbeline'' during that period. Garrick's version of ''Cymbeline'' would prove popular; it was staged a number of times over the next few decades.

In the late eighteenth century, Cymbeline was performed in Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

.

The play entered the Romantic era with

The play entered the Romantic era with John Philip Kemble

John Philip Kemble (1 February 1757 – 26 February 1823) was a British actor. He was born into a theatrical family as the eldest son of Roger Kemble, actor-manager of a touring troupe. His elder sister Sarah Siddons achieved fame with him on t ...

's company in 1801. Kemble's productions made use of lavish spectacle and scenery; one critic noted that during the bedroom scene, the bed was so large that Iachimo all but needed a ladder to view Imogen in her sleep. Kemble added a dance to Cloten's comic wooing of Imogen. In 1827, his brother Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

mounted an antiquarian production at Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

; it featured costumes designed after the descriptions of the ancient British by such writers as Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

and Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history ''Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which su ...

.

William Charles Macready

William Charles Macready (3 March 179327 April 1873) was an English actor.

Life

He was born in London the son of William Macready the elder, and actress Christina Ann Birch. Educated at Rugby School where he became headboy, and where now the t ...

mounted the play several times between 1837 and 1842. At the Theatre Royal, Marylebone

Marylebone (usually , also , ) is a district in the West End of London, in the City of Westminster. Oxford Street, Europe's busiest shopping street, forms its southern boundary.

An Civil parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish and latterly a ...

, an epicene

Epicenity is the lack of gender distinction, often reducing the emphasis on the masculine to allow the feminine. It includes androgyny – having both masculine and feminine characteristics. The adjective ''gender-neutral'' may describe epicenit ...

production was staged with Mary Warner, Fanny Vining, Anna Cora Mowatt

Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie (, Ogden; after first marriage, Mowatt; after second marriage, Ritchie; pseudonyms, Isabel, Henry C. Browning, and Helen Berkley; March 5, 1819July 21, 1870) was a French-born American author, playwright, public reader, ...

, and Edward Loomis Davenport

Edward Loomis Davenport (1816September 1, 1877) was an American actor.

Life and career

Born in Boston, he made his first appearance on the stage in Providence, Rhode Island in support of Junius Brutus Booth. Afterwards he went to England, where ...

.

In 1859, ''Cymbeline'' was first performed in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

. In the late nineteenth century, the play was produced several times in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

In 1864, as part of the celebrations of Shakespeare's birth, Samuel Phelps

Samuel Phelps (born 13 February 1804, Plymouth Dock (now Devonport), Plymouth, Devon, died 6 November 1878, Anson's Farm, Coopersale, near Epping, Essex) was an English actor and theatre manager. He is known for his productions of William ...

performed the title role at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

. Helena Faucit

Helena Saville Faucit, Lady Martin (11 October 1817 – 31 October 1898) was an English actress.

Early life

Born in London, she was the daughter of actors John Saville Faucit and Harriet Elizabeth Savill. Her parents separated when she was a gi ...

returned to the stage for this performance.

The play was also one of Ellen Terry

Dame Alice Ellen Terry, (27 February 184721 July 1928), was a leading English actress of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Born into a family of actors, Terry began performing as a child, acting in Shakespeare plays in London, and tour ...

's last performances with Henry Irving

Sir Henry Irving (6 February 1838 – 13 October 1905), christened John Henry Brodribb, sometimes known as J. H. Irving, was an English stage actor in the Victorian era, known as an actor-manager because he took complete responsibility ( ...

at the Lyceum

The lyceum is a category of educational institution defined within the education system of many countries, mainly in Europe. The definition varies among countries; usually it is a type of secondary school. Generally in that type of school the th ...

in 1896. Terry's performance was widely praised, though Irving was judged an indifferent Iachimo. Like Garrick, Irving removed the dream of Posthumus; he also curtailed Iachimo's remorse and attempted to render Cloten's character consistent. A review in the ''Athenaeum

Athenaeum may refer to:

Books and periodicals

* ''Athenaeum'' (German magazine), a journal of German Romanticism, established 1798

* ''Athenaeum'' (British magazine), a weekly London literary magazine 1828–1921

* ''The Athenaeum'' (Acadia U ...

'' compared this trimmed version to pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depicts ...

comedies such as ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wilton House in 1603 has b ...

''. The set design, overseen by Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, (; born Lourens Alma Tadema ; 8 January 1836 – 25 June 1912) was a Dutch painter who later settled in the United Kingdom becoming the last officially recognised denizen in 1873. Born in Dronryp, the Netherlands, ...

, was lavish and advertised as historically accurate, though the reviewer for the time complained of such anachronisms as gold crowns and printed books as props.

Similarly lavish but less successful was Margaret Mather

Margaret Mather (1859–1898) was a Canadian actress.

Biography

She was born in poverty in Tilbury, Ontario, as Margaret Finlayson, daughter of John Finlayson, a farmer and mechanic, and Ann Mather. She was one of the most famous Shakespearean ac ...

's production in New York in 1897. The sets and publicity cost $40,000, but Mather was judged too emotional and undisciplined to succeed in a fairly cerebral role.

Barry Jackson staged a modern dress

Modern dress is a term used in theatre and film to refer to productions of plays from the past in which the setting is updated to the present day (or at least to a more recent time period), but the text is left relatively unchanged. For example, ...

production for the Birmingham Rep

Birmingham Repertory Theatre, commonly called Birmingham Rep or just The Rep, is a producing theatre based on Centenary Square in Birmingham, England. Founded by Barry Jackson, it is the longest-established of Britain's building-based theatre c ...

in 1923, two years before his influential modern dress ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

''. Walter Nugent Monck brought his Maddermarket Theatre

The Maddermarket Theatre is a British theatre located in St. John's Alley in Norwich, Norfolk, England. It was founded in 1921 by Nugent Monck.

Early history and conversion

The theatre was originally built as a Roman Catholic chapel in 1794. In ...

production to Stratford in 1946, inaugurating the post-war tradition of the play.

London saw two productions in the 1956 season. Michael Benthall

Michael Pickersgill Benthall CBE (8 February 1919 – 6 September 1974) was an English theatre director.

Michael Benthall was the son of the British businessman and public servant Sir Edward Charles Benthall and of the Hon. Lady Benthall, ''née ...

directed the less successful production, at The Old Vic

The Old Vic is a 1,000-seat, nonprofit organization, not-for-profit producing house, producing theatre in Waterloo, London, Waterloo, London, England. Established in 1818 as the Royal Coburg Theatre, and renamed in 1833 the Royal Victoria Th ...

. The set design by Audrey Cruddas

Audrey Cruddas (1912–1979) was an English costume and scene designer, painter and potter.

Biography

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa, Cruddas moved to England with her parents when she was an infant. After leaving school she studied art at ...

was notably minimal, with only a few essential props. She relied instead on a variety of lighting effects to reinforce mood; actors seemed to come out of darkness and return to darkness. Barbara Jefford

Mary Barbara Jefford, OBE (26 July 1930 – 12 September 2020) was a British actress, best known for her theatrical performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, the Old Vic and the National Theatre and her role as Molly Bloom in the 1967 ...

was criticised as too cold and formal for Imogen; Leon Gluckman played Posthumus, Derek Godfrey

Derek Godfrey (3 June 1924 – 18 June 1983) was an English actor, associated with the Royal Shakespeare Company from 1960, who also appeared in several films and BBC television dramatisations during the 1960s and 1970s.

Born in London, he perfor ...

Iachimo, and Derek Francis

Derek Francis (7 November 1923 – 27 March 1984) was an English comedy and character actor.

Biography

Francis was a regular in the Carry On film players, appearing in six of the films in the 1960s and 1970s. He appeared in ''The Tomb of Lige ...

Cymbeline. Following Victorian practice, Benthall drastically shortened the last act.

By contrast, Peter Hall's production at the Shakespeare Memorial

William Shakespeare has been commemorated in a number of different statues and memorials around the world, notably his funerary monument in Stratford-upon-Avon (c. 1623); a statue in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey, London, designed by Willi ...

presented nearly the entire play, including the long-neglected dream scene (although a golden eagle designed for Jupiter turned out too heavy for the stage machinery and was not used). Hall presented the play as a distant fairy tale, with stylised performances. The production received favourable reviews, both for Hall's conception and, especially, for Peggy Ashcroft

Dame Edith Margaret Emily Ashcroft (22 December 1907 – 14 June 1991), known professionally as Peggy Ashcroft, was an English actress whose career spanned more than 60 years.

Born to a comfortable middle-class family, Ashcroft was deter ...

's Imogen. Richard Johnson Richard or Dick Johnson may refer to:

Academics

* Dick Johnson (academic) (1929–2019), Australian academic

* Richard C. Johnson (1930–2003), professor of electrical engineering

* Richard A. Johnson, artist and professor at the University of ...

played Posthumus, and Robert Harris Cymbeline. Iachimo was played by Geoffrey Keen

Geoffrey Keen (21 August 1916 – 3 November 2005) was an English actor who appeared in supporting roles in many films. He is well known for playing British Defence Minister Sir Frederick Gray in the ''James Bond'' films.

Biography

Early li ...

, whose father Malcolm

Malcolm, Malcom, Máel Coluim, or Maol Choluim may refer to:

People

* Malcolm (given name), includes a list of people and fictional characters

* Clan Malcolm

* Maol Choluim de Innerpeffray, 14th-century bishop-elect of Dunkeld

Nobility

* Máe ...

had played Iachimo with Ashcroft at the Old Vic in 1932.

Hall's approach attempted to unify the play's diversity by means of a fairy-tale topos

In mathematics, a topos (, ; plural topoi or , or toposes) is a category that behaves like the category of sheaves of sets on a topological space (or more generally: on a site). Topoi behave much like the category of sets and possess a notion ...

. The next major Royal Shakespeare Company

The Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) is a major British theatre company, based in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England. The company employs over 1,000 staff and produces around 20 productions a year. The RSC plays regularly in London, St ...

production, in 1962, went in the opposite direction. Working on a set draped with heavy white sheets, director William Gaskill

William "Bill" Gaskill (24 June 1930 – 4 February 2016) was a British theatre director who was "instrumental in creating a new sense of realism in the theatre". Described as "a champion of new writing", he was also noted for his productions of B ...

employed Brechtian

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a pl ...

alienation effect

The distancing effect, also translated as alienation effect (german: Verfremdungseffekt or ''V-Effekt''), is a concept in performing arts credited to German playwright Bertolt Brecht.

Brecht first used the term in his essay "Alienation Effects in ...

s, to mixed critical reviews. The acting, however, was widely praised. Vanessa Redgrave

Dame Vanessa Redgrave (born 30 January 1937) is an English actress and activist. Throughout her career spanning over seven decades, Redgrave has garnered numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Television Award, two ...

as Imogen was often compared favourably to Ashcroft; Eric Porter

Eric Richard Porter (8 April 192815 May 1995) was an English actor of stage, film and television.

Early life

Porter was born in Shepherd's Bush, London, to bus conductor Richard John Porter and Phoebe Elizabeth (née Spall). His parents hope ...

was a success as Iachimo, as was Clive Swift

Clive Walter Swift (9 February 1936 – 1 February 2019) was an English actor and songwriter. A classically trained actor, his stage work included performances with the Royal Shakespeare Company, but he was best known to television viewers for ...

as Cloten. Patrick Allen

John Keith Patrick Allen (17 March 1927 – 28 July 2006) was a British actor.

Life and career

Allen was born in Nyasaland (now Malawi), where his father was a tobacco farmer. After his parents returned to Britain, he was evacuated to Canada ...

was Posthumus, and Tom Fleming played the title role.

A decade later, John Barton's 1974 production for the RSC (with assistance from Clifford Williams) featured Sebastian Shaw in the title role, Tim Pigott-Smith

Timothy Peter Pigott-Smith, (13 May 1946 – 7 April 2017) was an English film and television actor and author. He was best known for his leading role as Ronald Merrick in the television drama series '' The Jewel in the Crown'', for which he wo ...

as Posthumus, Ian Richardson

Ian William Richardson (7 April 19349 February 2007) was a Scottish actor.

He portrayed the Machiavellian Tory politician Francis Urquhart in the BBC's '' House of Cards'' (1990–1995) television trilogy. Richardson was also a leading S ...

as Iachimo, and Susan Fleetwood

Susan Maureen Fleetwood (21 September 1944 – 29 September 1995) was a British stage, film, and television actress, who specialized in classical theatre. She received popular attention in the television series ''Chandler & Co'' and '' The Buddh ...

as Imogen. Charles Keating

Charles Humphrey Keating Jr. (December 4, 1923 – March 31, 2014) was an American sportsman, lawyer, real estate developer, banker, financier, conservative activist, and convicted felon best known for his role in the savings and loan sca ...

was Cloten. As with contemporary productions of ''Pericles'', this one used a narrator (Cornelius) to signal changes in mood and treatment to the audience. Robert Speaight

Robert William Speaight (; 1904 – 1976) was a British actor and writer, and the brother of George Speaight, the puppeteer.

Speaight studied under Elsie Fogerty at the Central School of Speech and Drama, then based in the Royal Albert Hal ...

disliked the set design, which he called too minimal, but he approved the acting.

In 1980, David Jones revived the play for the RSC; the production was in general a disappointment, although Judi Dench

Dame Judith Olivia Dench (born 9 December 1934) is an English actress. Regarded as one of Britain's best actresses, she is noted for her versatile work in various films and television programmes encompassing several genres, as well as for her ...

as Imogen received reviews that rivalled Ashcroft's. Ben Kingsley

Sir Ben Kingsley (born Krishna Pandit Bhanji; 31 December 1943) is an English actor. He has received various accolades throughout his career spanning five decades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Film Award, a Grammy Award, and two ...

played Iachimo; Roger Rees

Roger Rees (5 May 1944 – 10 July 2015) was a Welsh actor and director, widely known for his stage work. He won an Olivier Award and a Tony Award for his performance as the lead in ''The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby''. He also rece ...

was Posthumus. In 1987, Bill Alexander directed the play in The Other Place (later transferring to the Pit in London's Barbican Centre) with Harriet Walter playing Imogen, David Bradley as Cymbeline and Nicholas Farrell as Posthumus.

At the Stratford Festival

The Stratford Festival is a theatre festival which runs from April to October in the city of Stratford, Ontario, Canada. Founded by local journalist Tom Patterson in 1952, the festival was formerly known as the Stratford Shakespearean Festival ...

, the play was directed in 1970 by Jean Gascon

Jean Gascon (December 21, 1920 – April 13, 1988) was a Canadian opera director, actor, and administrator.

Career

Originally bent on a career in medicine, Gascon abandoned it for the stage after considerable work with amateur groups in Mont ...

and in 1987 by Robin Phillips

Robin Phillips OC (28 February 1940 – 25 July 2015) was an English actor and film director.

Life

He was born in Haslemere, Surrey in 1940 to Ellen Anne (née Barfoot) and James William Phillips. He trained at the Bristol Old Vic, where a c ...

. The latter production, which was marked by much-approved scenic complexity, featured Colm Feore

Colm Joseph Feore (; born August 22, 1958) is a Canadian actor. A 15-year veteran of the Stratford Festival, he is known for his Gemini-winning turn as Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in the CBC miniseries '' Trudeau'' (2002), his portrayal of G ...

as Iachimo, and as Imogen. The play was again at Stratford in 2004, directed by David Latham. A large medieval tapestry unified the fairly simple stage design and underscored Latham's fairy-tale inspired direction.

In 1994, Ajay Chowdhury directed an Anglo-Indian

Anglo-Indian people fall into two different groups: those with mixed Indian and British ancestry, and people of British descent born or residing in India. The latter sense is now mainly historical, but confusions can arise. The ''Oxford English ...

production of ''Cymbeline'' at the Rented Space Theatre Company. Set in India under British rule, the play features Iachimo, played by Rohan Kenworthy, as a British soldier and Imogen, played by Uzma Hameed, as an Indian princess.

At the new Globe Theatre

The Globe Theatre was a theatre in London associated with William Shakespeare. It was built in 1599 by Shakespeare's playing company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, on land owned by Thomas Brend and inherited by his son, Nicholas Brend, and gra ...

in 2001, a cast of six (including Abigail Thaw

Abigail J. Thaw (born 1 October 1965) is an English actress.

Early life

Abigail Thaw was born in London to actor John Thaw and his first wife, Sally Alexander, an academic/feminist activist who taught modern history at Goldsmiths College. Her ...

, Mark Rylance

Sir David Mark Rylance Waters (born 18 January 1960) is a British actor, playwright and theatre director. He is known for his roles on stage and screen having received numerous awards including an Academy Award, three BAFTA Awards, two Laurenc ...

, and Richard Hope) used extensive doubling for the play. The cast wore identical costumes even when in disguise, allowing for particular comic effects related to doubling (as when Cloten attempts to disguise himself as Posthumus.)

There have been some well-received theatrical productions including the Public Theater

The Public Theater is a New York City arts organization founded as the Shakespeare Workshop in 1954 by Joseph Papp, with the intention of showcasing the works of up-and-coming playwrights and performers.Epstein, Helen. ''Joe Papp: An American Li ...

's 1998 production in New York City, directed by Andrei Șerban

Andrei Șerban (born June 21, 1943) is a Romanian- American theater director. A major name in twentieth-century theater, he is renowned for his innovative and iconoclastic interpretations and stagings. In 1992 he became Professor of Theater at th ...

. ''Cymbeline'' was also performed at the Cambridge Arts Theatre

Cambridge Arts Theatre is a 666-seat theatre on Peas Hill and St Edward's Passage in central Cambridge, England. The theatre presents a varied mix of drama, dance, opera and pantomime. It attracts some of the highest-quality touring productions ...

in October 2007 in a production directed by Sir Trevor Nunn, and in November 2007 at the Chicago Shakespeare Theatre

Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST) is a non-profit, professional theater company located at Navy Pier in Chicago, Illinois. Its more than six hundred annual performances performed 48 weeks of the year include its critically acclaimed Shakespeare s ...

. The play was included in the 2013 repertory season of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival

The Oregon Shakespeare Festival (OSF) is a regional repertory theatre in Ashland, Oregon, United States, founded in 1935 by Angus L. Bowmer. The Festival now offers matinee and evening performances of a wide range of classic and contemporary pla ...

.

In 2004 and 2014, the Hudson Shakespeare Company The Hudson Shakespeare Company is a regional Shakespeare touring festival based in Jersey City in Hudson County, New Jersey, that produces an annual summer Shakespeare in the Park festival and often features lesser done Shakespeare works such as '' ...

of New Jersey produced two distinct versions of the play. The 2004 production, directed by Jon Ciccarelli, embraced the fairy tale aspect of the story and produced a colourful version with wicked step-mothers, feisty princesses and a campy Iachimo. The 2014 version, directed by Rachel Alt, went in a completely opposite direction and placed the action on ranch in the American Old West

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of American expansion in mainland North America that began with European colonial ...

. The Queen was a southern belle married to a rancher, with Imogen as a high society girl in love with the cowhand Posthumous.

In a 2007 Cheek by Jowl

Cheek by Jowl is an international theatre company founded in the United Kingdom by director Declan Donnellan and designer Nick Ormerod in 1981. Donnellan and Ormerod are Cheek by Jowl's artistic directors and together direct and design all of ...

production, Tom Hiddleston

Thomas William Hiddleston (born 9 February 1981) is an English actor. He gained international fame portraying Loki in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), starting with ''Thor'' in 2011 and most recently in the Disney+ series ''Loki'' in 2021 ...

doubled as Posthumus and Cloten.

In 2011, the Shakespeare Theatre Company of Washington, DC, presented a version of the play that emphasised its fable and folklore elements, set as a tale within a tale, as told to a child.

In 2012, Antoni Cimolino directed a production at the Stratford Festival