Cyanotype on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The cyanotype (from Ancient Greek κυάνεος - ''kuáneos'', “dark blue” + τύπος - ''túpos'', “mark, impression, type”) is a slow-reacting, economical photographic printing formulation sensitive to a limited near ultraviolet and blue light spectrum, the range 300 nm to 400 nm known as UVA radiation. It produces a cyan-blue print used for art as monochrome imagery applicable on a range of supports, and for

The cyanotype (from Ancient Greek κυάνεος - ''kuáneos'', “dark blue” + τύπος - ''túpos'', “mark, impression, type”) is a slow-reacting, economical photographic printing formulation sensitive to a limited near ultraviolet and blue light spectrum, the range 300 nm to 400 nm known as UVA radiation. It produces a cyan-blue print used for art as monochrome imagery applicable on a range of supports, and for

Since 2000 around 10 books, and in growing numbers, are published each year in English in which 'cyanotype' appears in the title, compared to only 95 in total from 1843–1999. Though it has been an artform since its inception, the numbers of artists now employing the cyanotype process have burgeoned, and they are not solely photographers. In the book of the 2022 British exhibition ''Squaring the Circles of Confusion: Neo-Pictorialism in the 21st Century'' eight contemporary artists: Takashi Arai, Céline Bodin, Susan Derges, David George, Joy Gregory,

Since 2000 around 10 books, and in growing numbers, are published each year in English in which 'cyanotype' appears in the title, compared to only 95 in total from 1843–1999. Though it has been an artform since its inception, the numbers of artists now employing the cyanotype process have burgeoned, and they are not solely photographers. In the book of the 2022 British exhibition ''Squaring the Circles of Confusion: Neo-Pictorialism in the 21st Century'' eight contemporary artists: Takashi Arai, Céline Bodin, Susan Derges, David George, Joy Gregory,

Mike Ware's New Cyanotype

– A new version of the cyanotype that address some of the classical cyanotype's shortcomings as a photographic process.

on AlternativePhotography.com * * {{Authority control Photographic processes dating from the 19th century Non-impact printing Alternative photographic processes History of photography

The cyanotype (from Ancient Greek κυάνεος - ''kuáneos'', “dark blue” + τύπος - ''túpos'', “mark, impression, type”) is a slow-reacting, economical photographic printing formulation sensitive to a limited near ultraviolet and blue light spectrum, the range 300 nm to 400 nm known as UVA radiation. It produces a cyan-blue print used for art as monochrome imagery applicable on a range of supports, and for

The cyanotype (from Ancient Greek κυάνεος - ''kuáneos'', “dark blue” + τύπος - ''túpos'', “mark, impression, type”) is a slow-reacting, economical photographic printing formulation sensitive to a limited near ultraviolet and blue light spectrum, the range 300 nm to 400 nm known as UVA radiation. It produces a cyan-blue print used for art as monochrome imagery applicable on a range of supports, and for reprography

Reprography (a portmanteau of ''reproduction'' and ''photography'') is the reproduction of graphics through mechanical or electrical means, such as photography or xerography. Reprography is commonly used in catalogs and archives, as well as in th ...

in the form of blueprints. For any purpose, the process usually uses two chemicals: ferric ammonium citrate

Ammonium ferric citrate (also known as Ferric Ammonium Citrate or Ammoniacal ferrous citrate) has the formula (NH4)5 e(C6H4O7)2 A distinguishing feature of this compound is that it is very soluble in water, in contrast to ferric citrate which is ...

or ferric ammonium oxalate

Ferric ammonium oxalate (ammonium ferrioxalate) is the ammonium salt of the anionic trisoxalato coordination complex of iron(III). It is a precursor to iron oxides, diverse coordination polymers, and Prussian Blue

Prussian blue (also known as ...

, and potassium ferricyanide

Potassium ferricyanide is the chemical compound with the formula K3 e(CN)6 This bright red salt contains the octahedrally coordinated 3−.html" ;"title="e(CN)6sup>3−">e(CN)6sup>3− ion. It is soluble in water and its solution shows some g ...

, and only water to develop and fix. Announced in 1842, it is still in use.

History

The cyanotype was discovered, and named thus, bySir John Herschel

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet (; 7 March 1792 – 11 May 1871) was an English polymath active as a mathematician, astronomer, chemist, inventor, experimental photographer who invented the blueprint and did botanical wor ...

who in 1842 published his investigation of light on iron compounds, expecting that photochemical reactions would reveal, in form visible to the human eye, the infrared

Infrared (IR), sometimes called infrared light, is electromagnetic radiation (EMR) with wavelengths longer than those of visible light. It is therefore invisible to the human eye. IR is generally understood to encompass wavelengths from around ...

extreme of the electromagnetic spectrum

The electromagnetic spectrum is the range of frequencies (the spectrum) of electromagnetic radiation and their respective wavelengths and photon energies.

The electromagnetic spectrum covers electromagnetic waves with frequencies ranging from ...

detected by his father and the ultra-violet or ‘actinic

Actinism () is the property of solar radiation that leads to the production of photochemical and photobiological effects. ''Actinism'' is derived from the Ancient Greek ἀκτίς, ἀκτῖνος ("ray, beam"). The word ''actinism'' is found, ...

’ rays that had been discovered in 1801 by Johann Ritter. Though Döbereiner had published in 1831 in German on the light-sensitivity of ferric oxalate

Ferric oxalate, also known as iron(III) oxalate, is a chemical compound composed of ferric ions and oxalate ligands; it may also be regarded as the ferric salt of oxalic acid. The anhydrous material is pale yellow; however, it may be hydrated to f ...

, of which Herschel became aware during his visit to Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

, it is too lightly toned to form a satisfactory image and would require a second reaction to make a permanent print.

Alfred Smee

Alfred Smee FRS, FRCS (18 June 1818, Camberwell – 11 January 1877, Finsbury Circus) was an English surgeon, chemist, metallurgist, electrical researcher and inventor. He was also an orchid enthusiast.

Born the second son of William Smee, acc ...

had in 1840 used electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is the branch of physical chemistry concerned with the relationship between electrical potential difference, as a measurable and quantitative phenomenon, and identifiable chemical change, with the potential difference as an outco ...

to isolate a pure form of potassium ferricyanide, which he sent to Herschel whose innovation was to use the ammonium iron(III) citrate

Ferric citrate or iron(III) citrate describes any of several complexes formed upon binding any of the several conjugate bases derived from citric acid with ferric ions. Most of these complexes are orange or red-brown. They contain two or more Fe ...

or tartrate, then commercially available as an iron tonic and also introduced to him by Smee, for photographic purpose. He mixed the ammonium ferric citrate in a 20% aqueous solution, with 16% of the potassium ferricyanide, to make the sensitizer for coating plain paper. Exposed to sunlight, the ferric salt is reduced then combines with the ferricyanide to yield ferric ferrocyanide; Prussian blue (also known as Turnbull’s blue, or Berlin Blue in Germany). Intensifying and fixing is achieved simply by rinsing the print in water in which unexposed sensitizer and reaction products are readily soluble.

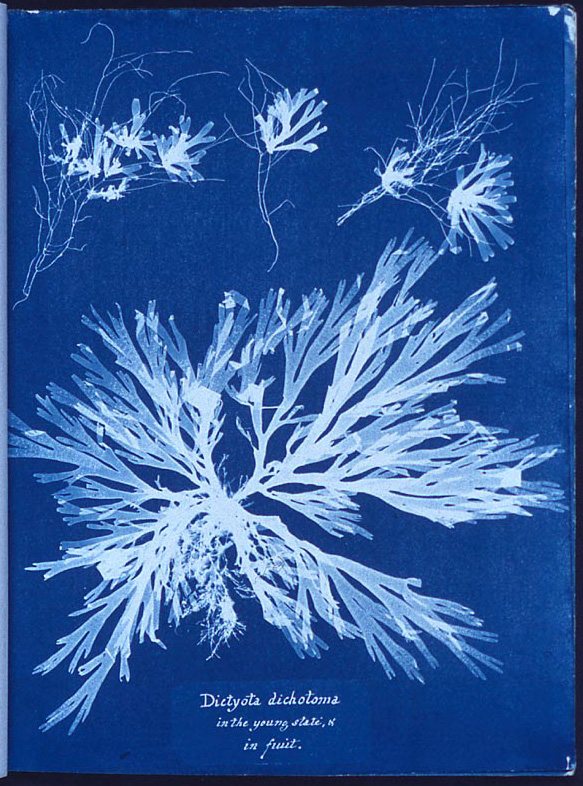

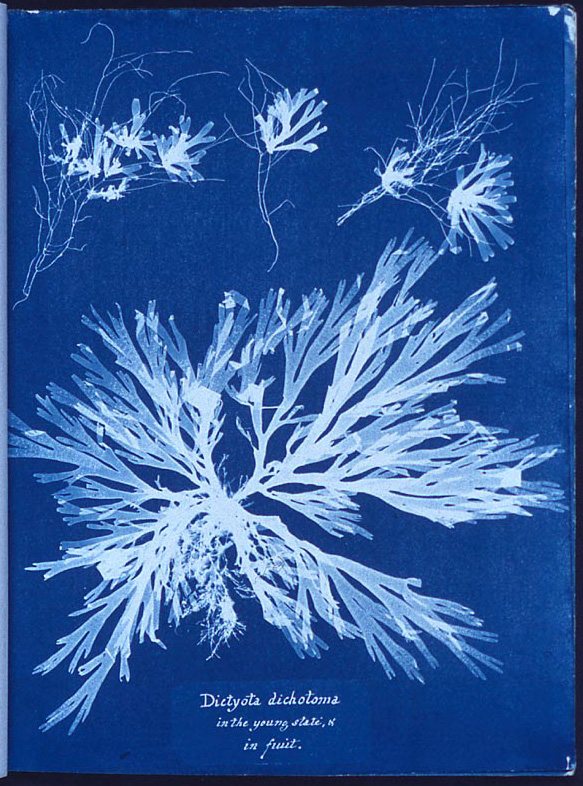

Anna Atkins

Anna Atkins (née Children; 16 March 1799 – 9 June 1871) was an English botanist and photographer. She is often considered the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographic images. Some sources say that she was the first woma ...

, a friend of the Herschel family, over 1843–61 and with the assistance of Anne Dixon, hand-printed several albums of botanical and textile specimens, especially ''Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions,'' effectively the world’s first photographically-illustrated books. After the Ross Antarctic Expedition (1839–1843) John Davis, artist and naturalist on the expedition, made or commissioned some cyanotypes in 1848 from seaweeds collected on the voyage. Also in the Antipodes, Herbert Dobbie in imitation of Atkins produced a book ''New Zealand ferns: 148 varieties,'' but with double-sided pages of cyanotype prints, in 1880.

John Mercer in the 1850s used the process for printing photographs onto cotton textiles and discovered means of toning the cyanotype violet, green, brown, red, or black.

As with all of his photographic inventions, Herschel did not patent his cyanotype process. Chemist George Thomas Fisher Jr. quickly disseminated information on the new medium internationally in his popular 1843 fifty-page manual ''Photogenic manipulation, containing plain instructions in the theory and practice of the arts of photography: calotype, cyanotype, ferrotype, chrysotype, anthotype, daguerreotype, and thermography,'' which the following year was translated into German and Dutch. The medium was immediately taken up and perfected by notable photographic practitioners of the time, including William Henry Fox Talbot

William Henry Fox Talbot FRS FRSE FRAS (; 11 February 180017 September 1877) was an English scientist, inventor, and photography pioneer who invented the salted paper and calotype processes, precursors to photographic processes of the later ...

and Henry Bosse. The latter in making fine presentation albums of bridges and structural steel, foresaw an appropriate effect in colour: the intense blues of his refined cyanotypes from large glass plates were printed on fine French paper 37 cm x 43.6 cm, watermarked ''Johannot et Cie. Annonay, aloe's satin'' and leather bound.

Commercial use came only in 1872, the year after Herschel's death. Marion and Company of Paris were first to market the cyanotype, under the proprietary name of “Ferro-prussiate,” for reprography of plans and technical drawings and to advantage due to its low cost and simplicity of processing which required only water. In this application and with the manufacture of blueprint papers, it remained the dominant reprographic process until the 1940s. During the 217-day Siege of Mafeking

The siege of Mafeking was a 217-day siege battle for the town of Mafeking (now called Mafikeng) in South Africa during the Second Boer War from October 1899 to May 1900. The siege received considerable attention as Lord Edward Cecil, the son of ...

of the town of Mafeking (Mafikeng

Mafikeng, officially known as Mahikeng and previously Mafeking (, ), is the capital city of the North West province of South Africa.

Close to South Africa's border with Botswana, Mafikeng is northeast of Cape Town and west of Johannesburg. In ...

) in South Africa during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

from October 1899, the process was used to print stamps and banknotes.

On the other hand the simple technology of the cyanotype remained accessible in the non-industrial realm and contributed to folk art

Folk art covers all forms of visual art made in the context of folk culture. Definitions vary, but generally the objects have practical utility of some kind, rather than being exclusively decorative art, decorative. The makers of folk art a ...

; Francois Brunet notes the cyanotypes on cloth used by American home quilt-makers after 1880, and Geoffrey Batchen cites thirty or more early cyanotyped family snapshots on cloth, sewn into pillow slips or quilts, in the collection of Eastman House. Sandra Sider

Sandra Sider (born 1949, in Alabama) is an American quilt artist, author, and curator. She holds a PhD in comparative literature from University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, specializing in Renaissance studies. She also holds an M.A. in art ...

perpetuates this tradition in her own quilt making and as a proponent for increased museum acquisitions of Art Quilts.

The cyanotype produced negatives, reversing the darks and lights of the image or object exposed on it, but Herschel also contrived a version, though more complex, to produce positives which he hoped would aid in his ambition to achieve images of full natural colour. Its difficulties were overcome by Henri Pellet in 1877 in his gum arabic iron ''cyanofer'' direct positive photographic tracing method, which he commercialised.

Process

Herschel's formula and method

In a typical procedure, equal volumes of an 8.1% (w/v) solution of potassium ferricyanide and a 20% solution of ferric ammonium citrate are mixed. The overall contrast of the sensitizer solution can be increased with the addition of approximately 6 drops of 1% ( w/v) solutionpotassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate, , is a common inorganic chemical reagent, most commonly used as an oxidizing agent in various laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is acutely and chronically harmful to health ...

for every 2 ml of sensitizer solution.

This mildly photosensitive Photosensitivity is the amount to which an object reacts upon receiving photons, especially visible light. In medicine, the term is principally used for abnormal reactions of the skin, and two types are distinguished, photoallergy and phototoxicity. ...

solution is then applied to a receptive surface (such as paper or cloth) and allowed to dry in a dark place. Cyanotypes can be printed on any support capable of soaking up the iron solution. Although watercolor

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to t ...

paper is a preferred medium, cotton, wool

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As ...

and even gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

sizing

Sizing or size is a substance that is applied to, or incorporated into, other materials—especially papers and textiles—to act as a protective filler or glaze. Sizing is used in papermaking and textile manufacturing to change the absorption ...

on nonporous

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. "empty") spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measure ...

surfaces have been used. Care should be taken to avoid alkaline-buffered papers, which degrade the image over time.

An image can be produced by exposing sensitised paper to a source of ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nanometer, nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 Hertz, PHz) to 400 nm (750 Hertz, THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than ...

light (such as sunlight) as a contact print

A contact print is a photographic image produced from film; sometimes from a film negative, and sometimes from a film positive or paper negative. In a darkroom an exposed and developed piece of film or photographic paper is placed emulsion si ...

. The combination of UV light and the citrate reduces the iron(III) to iron(II). This is followed by a complex reaction of the iron(II) with ferricyanide. The result is an insoluble, blue pigment (ferric ferrocyanide) known as Prussian blue

Prussian blue (also known as Berlin blue, Brandenburg blue or, in painting, Parisian or Paris blue) is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula Fe CN)">Cyanide.html" ;"title="e(Cyani ...

. The exposure time varies widely, from a few seconds in strong direct sunlight, to 10–20 minute exposures on a dull day.

After exposure, the paper is developed by washing in cold running water: the water-soluble iron(III) salts are washed away. The parts that were exposed to ultraviolet turn blue as the non-water-soluble Prussian blue pigment remains in the paper. This is what gives the print its typical blue color. The blue color darkens upon drying.

Improved formula

The ingredients have remained mostly unchanged since its inception in 1840. In 1994 Mike Ware improved on Herschel's formula with ammonium iron(III) oxalate, also known asferric ammonium oxalate

Ferric ammonium oxalate (ammonium ferrioxalate) is the ammonium salt of the anionic trisoxalato coordination complex of iron(III). It is a precursor to iron oxides, diverse coordination polymers, and Prussian Blue

Prussian blue (also known as ...

, to replace the variable and unreliable ammonium ferric citrate. It has the advantages of being made up as a convenient single stock solution with a good shelf-life that does not nourish mould growth. The solution is well-absorbed by paper fibres, so does not pool on the surface or result in a ‘tackiness’ which may adhere to negatives. The paper better retains the pigment, with little of the Prussian blue image being lost in the washing stage, and exposure is shorter (ca. 4-8 times) than the traditional process. The cyanotype solution, even once its excess is washed off with water, remains photo-sensitive to some degree. A print that has been stored or displayed in bright light will eventually fade, the light causing a chemical reaction that changes the Prussian blue of the cyanotype to white. However, this process can be reversed by storing the cyanotypes in darkness. This will return them to their original vibrancy.

Different composition levels of ferric ammonium citrate

Ammonium ferric citrate (also known as Ferric Ammonium Citrate or Ammoniacal ferrous citrate) has the formula (NH4)5 e(C6H4O7)2 A distinguishing feature of this compound is that it is very soluble in water, in contrast to ferric citrate which is ...

(or oxalate) and potassium ferricyanide

Potassium ferricyanide is the chemical compound with the formula K3 e(CN)6 This bright red salt contains the octahedrally coordinated 3−.html" ;"title="e(CN)6sup>3−">e(CN)6sup>3− ion. It is soluble in water and its solution shows some g ...

will result in a variety of effects in the final cyanotypes. Mixtures of half ferric ammonium citrate

Ammonium ferric citrate (also known as Ferric Ammonium Citrate or Ammoniacal ferrous citrate) has the formula (NH4)5 e(C6H4O7)2 A distinguishing feature of this compound is that it is very soluble in water, in contrast to ferric citrate which is ...

and half potassium ferricyanide will produce a medium, even shade of blue that is most commonly seen in a cyanotype. A mix of one third ferric ammonium citrate and two thirds potassium ferricyanide will produce a darker blue, and a more high-contrast final print.

Disadvantages of the Ware formula are a higher cost, more complicated preparation, and a level of toxicity.

Blue Flash formula

YouTuber Prussian blues developed this formula that drastically cuts exposure time and gives a good tone range with normal negatives, unlike the classic cyanotype which needs correction curves to get a good tone range. A thin coat of 20% Ferric Ammonium Oxalate solution is used to sensitize the paper (it needs to be as thin as possible to work properly). Ferric Ammonium Oxalate solution is sensitive to UV light on its own so it needs to be kept in a light-tight container. After the paper is dry it can be exposed where exposure can be different depending on the UV light source, but 35–40 seconds of direct sunlight is a good starting point. There will be no visible difference to the paper after exposure. For development, 5% Potassium Ferrocyanide can be used with added Sulfamic acid to get PH of 3-4. Developing is needed for at least a few seconds but not more. The developer can be reused. Then wash with 2% Citric acid solution. After that wash in water and dry.Printmaking

The simplest kind of cyanotype print is aphotogram

A photogram is a photographic image made without a camera by placing objects directly onto the surface of a light-sensitive material such as photographic paper and then exposing it to light.

The usual result is a negative shadow image th ...

, made by arranging objects on sensitised paper. Fresh or pressed plants are a typical subject but any opaque to translucent object will create an image. A sheet of glass will press flat objects into close contact with the paper, resulting in a sharp image. Otherwise, three-dimensional objects or less than perfectly flat ones will create a more or less blurred image depending on the incidence and breadth of the light source.

A variant of photograms are chemigram

A chemigram (from "chemistry" and ''gramma'', Greek for "things written") is an experimental piece of art where an image is made by painting with chemicals on light-sensitive paper (such as photographic paper).

The term ''Chemigram'' was coined ...

s. The cyanotype solution is applied, poured or sprayed irregularly. A variant of action painting results from repeated washing and application, placing objects on top.

More sophisticated prints can be made from artwork or photographic images on transparent or translucent media. The cyanotype process reverses light and dark, so a negative original is required to print as a positive image. Large format photographic negatives or transparent digital negatives can produce images with a full tonal range, or lithographic film can be used to create high-contrast images.

The cyanotype may be combination-printed with gumoil, or with a gum bichromate

Gum bichromate is a 19th-century photographic printing process based on the light sensitivity of dichromates. It is capable of rendering painterly images from photographic negatives. Gum printing is traditionally a multi-layered printing process, ...

image, in which, for full-colour imaging from colour separations, it may form the blue layer; or it may be combined with a hand-painted or hand-drawn drawn layer.

Toning

In a cyanotype, blue is usually the desired color. However, a variety of alternative effects can be achieved. These fall into three categories: reducing, intensifying, and toning. It is common to bleach prints before toning them, but also possible to achieve different effects by toning prints without bleaching. * Bleaching processes are ways of decreasing the intensity of the blue.Sodium carbonate

Sodium carbonate, , (also known as washing soda, soda ash and soda crystals) is the inorganic compound with the formula Na2CO3 and its various hydrates. All forms are white, odourless, water-soluble salts that yield moderately alkaline solutions ...

, ammonia, borax, Dektol photographic developer and other chemicals can be used to do this. Household bleach is also effective, but tends to destroy the paper base. How much and how long to bleach depends on the image content, emulsion thickness and what kind of toning is being used. When using a bleaching agent it is important to control the bleaching process by washing in clean water as soon as the desired effect is achieved, to prevent loss of detail in the highlights.

* Intensifying processes will strengthen the blue effect. Chemicals used are hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

or mild acidic substances: citric acid, lemon juice, vinegar or acetic acid etc. These can also used to speed up the oxidation process that creates the blue pigment.

* Toning processes are used to change the color of the iron oxide in the print. The color change varies with the reagent used. A variety of agents can be used, including various types of tea, coffee, wine, urine, tannic acid or pyrogallic acid, resulting in tones varying from brown to black. Most toning processes will to some extent tint the white parts of a print.

Long-term preservation

One of the most robust of Victorian print technologies, cyanotypes are quite stable on their own, but in contrast to most historical and present-day processes, the prints do not react well tobasic

BASIC (Beginners' All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code) is a family of general-purpose, high-level programming languages designed for ease of use. The original version was created by John G. Kemeny and Thomas E. Kurtz at Dartmouth College ...

environments. As a result, it is not advised to store or present the print in chemically buffered museum board, as this makes the image fade. Another unusual characteristic of the cyanotype is its regenerative behavior: prints that have faded due to prolonged exposure to light can often be significantly restored to their original tone by simply temporarily storing them in a dark environment.

Cyanotypes on cloth are permanent but must be washed by hand with non-phosphate soap so as to not turn the cyan to yellow.

Cyanotype in artistic practice

Artistic potential

The cyanotype's success as a form of artistic expression lies in its capacity for manipulation or distortion. It produces distinctive effects and is versatile, enabling prints to be made on a wide variety of surfaces, including paper, wood, fabric, glass,Perspex

Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) belongs to a group of materials called engineering plastics. It is a transparent thermoplastic. PMMA is also known as acrylic, acrylic glass, as well as by the trade names and brands Crylux, Plexiglas, Acrylite ...

, bone, shell and eggshell, plaster and ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcelain ...

s and at any scale; to date 2017, the largest is 276.64 m (2977.72 ft), created by Stefanos Tsakiris in Thessaloniki, Greece, on 18 September 2017. Robin Hill in 2001 exhibited ''Sweet Everyday'', a 30.5 m (100 ft) cyanotype enwrapping Lennon, Weinberg, Inc.'s Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

gallery, and evoking wavy brushstrokes by placing ordinary shopping bags on photo-sensitive paper exposed to light. For photographic negatives or positives enlargement directly onto the emulsion is not feasible due to the low sensitivity of the emulsion (except with a solar enlarger), so requires contact printing at 1:1 ratio. The low sensitivity permits progress to be inspected in a printing frame during exposure. Consequently and because of its long exposure scale it suits most negatives whether of high or low contrast. As a recognisably 19th century technology, artists like John Dugdale use it to evoke, or to critique, Victorian aesthetics and soclal constructs.

The artist is not restricted to the reproduction of existing photographic negatives. Prints can be made of three-dimensional objects, utilising the ability of the objects to be placed on top of the photosensitive material. Once exposed to light, the final print is of an outline of an item with internal detail where they allow light, depending on their relative transparency and exposure, to filter through; Anna Atkin's botanical cyanotypes sharply register the more transparent segments of a petal or leaf. An object original, used to make a cyanotype photogram, including the human figure for example, is reproduced at actual size. Robert Rauschenberg

Milton Ernest "Robert" Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the Pop art movement. Rauschenberg is well known for his Combines (1954–1964), a group of artwor ...

's and Susan Weil’s collaborative cyanotypes, including ''Untitled (Double Rauschenberg)'', c.1950 were made by both artists lying down, hands held, on a large piece of photosensitive paper (treated with cyanotype chemicals). The resulting prints of their bodies in various poses are currently part of the Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) is an art museum located in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, on 53rd Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues.

It plays a major role in developing and collecting modern art, and is often identified as one of ...

’s permanent collection.

The powerful cyan hue may evolve a spiritual or emotional response as in the cosmic imagery of Carolyn Lewens and naturally associates symbolically with sea or sky. As German photographer Thomas Kellner notes of his 1997 Cubist multi-pinhole portraits of porcelain dolls; "I am specially happy with the blue colour in this series as the blue has a different depth in the background than a black print. Blue is still infinite, whereas black usually has the character of ending." The negative form may be disorienting or surreal; while white is often used to frame or highlight a central subject in many artistic media, the opposite may be true in the cyanotype, requiring the artist to adapt their ideas to the effect.

Equally important is the expressive potential of the application of emulsion using brush, squeegee, roller or cloth, or by stamping, for calligraphic

Calligraphy (from el, link=y, καλλιγραφία) is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instrument. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as ...

effect.

Artists

Nineteenth century

Britain

Anna Atkins, who was also an accomplished watercolorist, in her cyanotype botanical specimens, is considered the first to make art with the medium in which the sea plants appear suspended in an oceanic blue, and while her hundreds of images satisfy a scientific curiosity, their aesthetic quality has served as inspiration for cyanotype artists ever since. Cyanotype photography was popular in Victorian England, but became less popular as photography improved. By the mid-1800s few photographers continued to exploit its accessible qualities and at theGreat Exhibition

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition (in reference to the temporary The Crystal Palace, structure in which it was held), was an International Exhib ...

of 1851, despite extensive displays of photographic technology, only a single example of the cyanotype process was included. Peter Henry Emerson

Peter Henry Emerson (13 May 1856 – 12 May 1936) was a British writer and photographer. His photographs are early examples of promoting straight photography as an art form. He is known for taking photographs that displayed rural settings and f ...

exemplified the British attitude that cyanotypes were unworthy of purchase or exhibition with his assertion that: “No one but a vandal would print a landscape in red, or in cyanotype.”

Consequently, the process devolved to the proofing of domestic negatives by hobbyist photographers and to postcards, though another British scientist, Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society

(Whatever shines should be observed)

, predecessor =

, successor =

, formation =

, founder =

, extinction =

, merger =

, merged =

, type = NGO ...

Washington Teasdale, delivered hundreds of lectures throughout his lifetime and was among the first to illustrate them with lantern slides

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a sin ...

, and, up to 1890, to record his experiments and specimens, used the cyanotype, a collection of which is held at the Museum of the History of Science, Oxford

The History of Science Museum in Broad Street, Oxford, England, holds a leading collection of scientific instruments from Middle Ages to the 19th century. The museum building is also known as the Old Ashmolean Building to distinguish it from th ...

.

Edwin Linley Sambourne used cyanotypes as an archive of reference images for his ''Punch'' cartoons.

France

Curators and practitioners in France embraced the process. Caricaturist, illustrator, writer and portrait photographerBertall

Charles Albert d'Arnoux (Charles Constant Albert Nicolas, Vicomte d'Arnoux, Count of Limoges-Saint-Saëns), known as ''Bertall'' (or Bertal, an anagram of Albert) or Tortu-Goth (December 18, 1820 in Paris – March 24, 1882 in Soyons) was a Fren ...

(born Charles Albert, vicomte d’ Arnoux, comte de Limoges-Saint-Saëns) as partner of Hippolyte Bayard

Hippolyte Bayard (20 January 1801 – 14 May 1887) was a French photographer and pioneer in the history of photography. He invented his own process that produced direct positive paper prints in the camera and presented the world's first public e ...

was commissioned in the 1860s to make cyanotype portraits from glass negatives for the Société d’Ethnographie for their publication ''Collection Anthropologique''. While artistic in execution they also satisfy with the scientific interests of the group as each subject is photographed nude with front, back and profile views, not in the field but in his studio. The project also takes advantage of the ease of making multiples of cyanotypes for the publication Henri Le Secq

Jean-Louis-Henri Le Secq des Tournelles (18 August 1818 – 26 December 1882) was a French painter and photographer. After the French government made the daguerreotype open for public in 1839, Le Secq was one of the five photographers selected ...

's cyanotypes, which he made after he gave up photography after 1856 to continue painting and collecting art, were reprints of his famous works and made around 1870 as he was afraid of possible loss due to fading. He gave the reprints dates of the original negatives, some of which are still in good condition. They are well-represented in French collections. From the early 1850s through the 1870s Corot, with associated artists working in and near the town Barbizon

Barbizon () is a commune (town) in the Seine-et-Marne department in north-central France. It is located near the Fontainebleau Forest.

Demographics

The inhabitants are called ''Barbizonais''.

Art history

The Barbizon school of painters is name ...

adopted the hand-drawn '' cliché-verre'', and though most were printed on salted or albumenized paper, some used the cyanotype.

America

In the US the medium persevered into the 20th century.Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection. He adopted the first ...

made cyanotype contact prints of his animal locomotion sequences, and Edward Curtis

Edward Sherriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people. Sometimes referred to as the "Shadow Catcher", Curtis traveled ...

' ethnographic cyanotypes of native North Americans are preserved in the George Eastman House

The George Eastman Museum, also referred to as ''George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film'', the world's oldest museum dedicated to photography and one of the world's oldest film archives, opened to the public in 1949 in ...

.

Pictorialism

Pictorialists, throughout Europe and other western countries, in efforts to have photography accepted as an art form, emphasised handcraft in printing, in imitation of painting and drawing, and drew onSymbolist

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and realis ...

subject matter and themes. Many of the practitioners were respected amateurs whose work was rewarded in a system of International 'salons' run by such organisations as the Camera Club of New York, and competition promoted an elevated level of technical experimentation with all of the then-current processes, such as calotypy, cyanotypy, gum printing Gum printing is a way of making photographic reproductions without the use of silver halides. The process uses salts of dichromate in common with a number of other related processes such as sun printing.

When mixtures of mucilaginous, protein-cont ...

, platinum print

Platinum prints, also called ''platinotypes'', are photographic prints made by a monochrome photographic printing, printing process involving platinum.

Platinum tones range from warm black, to reddish brown, to expanded mid-tone grays that are ...

ing, bromoil and Autochrome colour.

Clarence White

Clarence White (born Clarence Joseph LeBlanc; June 7, 1944 – July 15, 1973) was an American bluegrass and country guitarist and singer. He is best known as a member of the bluegrass ensemble the Kentucky Colonels and the rock band the Byrd ...

's impeccable domestic and plein-air pictures are indebted in their bold composition to his contemporaries the painters Thomas Wilmer Dewing, William Merritt Chase

William Merritt Chase (November 1, 1849October 25, 1916) was an American painter, known as an exponent of Impressionism and as a teacher. He is also responsible for establishing the Chase School, which later would become Parsons School of Design. ...

and John White Alexander

John White Alexander (7 October 1856 – 31 May 1915) was an American portrait, figure, and decorative painter and illustrator.

Early life

Alexander was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, now a part of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Orphaned in in ...

. His labor-intensive process entailed developing the negatives then making tests on cyanotype, playing with dimensions, proportions, and other variables, before making a print in platinum, which he then meticulously and expressively retouched. Alfred Steiglitz

Alfred Stieglitz (January 1, 1864 – July 13, 1946) was an American photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his 50-year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz was kno ...

in White's portrait of him (1907) held in Princeton University Art Museum, appears gloweringly critical in the cyanotype print preserved there.

At the turn of the century, painter-photographer Edward Steichen

Edward Jean Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourgish American photographer, painter, and curator, renowned as one of the most prolific and influential figures in the history of photography.

Steichen was credited with tr ...

, then associated with Alfred Steiglitz who promoted the Photo-Secession

The Photo-Secession was an early 20th century movement that promoted photography as a fine art in general and photographic pictorialism in particular.

A group of photographers, led by Alfred Stieglitz and F. Holland Day in the early 20th century ...

and Pictorialism through his ''Camera Work

''Camera Work'' was a quarterly photographic journal published by Alfred Stieglitz from 1903 to 1917. It presented high-quality photogravures by some of the most important photographers in the world, with the goal to establish photography as a ...

'' (1903–1917) produced prints of ''Midnight Lake George'' now held in ''The Alfred Stieglitz Collection: Photographs'' at the Art Institute of Chicago where in 2007 scientific examination of the prints and his records concluded that cyanotype had been incorporated in their predominant gum bichromate over platinum production. Steichen argued provocatively in the first issue of ''Camera Work'' that “every photograph is a fake from start to finish, a purely impersonal, unmanipulated photograph being practically impossible.”

Photo-Secessionist Franco-American Paul Burty-Havilland, involved through marriage with the Lalique company, evinces a Japonisme

''Japonisme'' is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858. Japon ...

in his moody cyanotype portraits and nudes made between 1898–1920. Another American Pictorialist Fred Holland Day

Fred Holland Day (23 July 1864—23 November 1933), known professionally as F. Holland Day, was an American photographer and publisher. He was prominent in literary and photography circles in the late nineteenth century and was a leading Pict ...

made cyanotypes of youths, nude or in sailor suits, in 1911, that are held in the Library of Congress, and French artist Charles-François Jeandel printed his erotic imagery of bound women in his painting workshop in Paris and then in Charente 1890–1900.

The more traditional American printmaker Bertha Jaques

Bertha Evelyn Jaques (October 24, 1863 – March 30, 1941) was an American etcher and cyanotype photographer. Jaques helped found the Chicago Society of Etchers, an organization that would become internationally significant for promoting etching ...

, aligned with the antimodernist views of the late Victorian Arts and Crafts movement, from 1894 produced more than a thousand cyanotype photographs of wildflowers.

Impressionism

American artistTheodore Robinson

Theodore Robinson (June 3, 1852April 2, 1896) was an American painter best known for his Impressionist landscapes. He was one of the first American artists to take up Impressionism in the late 1880s, visiting Giverny and developing a close frien ...

painted in Giverny

Giverny () is a commune in the northern French department of Eure.Commune de Giverny (27285)< ...

1887–1892, contemporaneous with Monet

Oscar-Claude Monet (, , ; 14 November 1840 – 5 December 1926) was a French painter and founder of impressionist painting who is seen as a key precursor to modernism, especially in his attempts to paint nature as he perceived it. During ...

of whom he made a portrait in cyanotype, and of the haystacks that Monet famously painted. He noted that “Painting directly from nature is difficult as things do not remain the same; the camera helps to retain the picture in your mind.” He often drew a grid over his cyanotypes or albumen prints to assist transferring the composition, with compositional amendments, onto canvas, though conscious that “I must beware of the photo, get what I can of it and then go.” His photographic imagery is held in the Canajoharie Library and Art Gallery and the Terra Foundation for the Arts.

Modernism

Arthur Wesley Dow

Arthur Wesley Dow (1857 – December 13, 1922) was an American painter, printmaker, photographer and an arts educator.

Early life

Arthur Wesley Dow was born in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1857. Dow received his first art training in 1880 from An ...

's modernist approach was inlfuential on the Pictorilaists in the eloquently simple compositions of his New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

environment, like ''Pine Tree'' (1895), a cyanotype, related to his interest, while studying in France, in the flat, decorative qualities of Japanese art and that of Les Nabis.

In Europe, Josef Sudek

Josef Sudek (17 March 1896 – 15 September 1976) was a Czech photographer, best known for his photographs of Prague.

Life

Sudek was born in Kolín, Bohemia. He was originally a bookbinder. During the First World War he was drafted into the A ...

, the 'Poet of Prague' sometimes employed the cyanotype to impressionist effect during the early Modernist period.

Milan-born photographer, printmaker, painter, set designer and experimental film-maker, Luigi Veronesi

Luigi Veronesi (28 May 1908 – 25 February 1998) was an Italian photographer, painter, scenographer and film director born in Milan.

Early career

Luigi Veronesi trained as textile designer in the 1920s and by practised photography. He was ...

, well-informed about the international debate on abstraction, was impressed with the abstract potential of the photogram. He participated in a 1934 exhibition in Paris with the international group of abstract artists ' Abstraction-Création', through which he met with Fernand Léger

Joseph Fernand Henri Léger (; February 4, 1881 – August 17, 1955) was a French painting, painter, sculpture, sculptor, and film director, filmmaker. In his early works he created a personal form of cubism (known as "tubism") which he gradually ...

. He drew inspiration from Léger’s ''Ballet Mécanique

''Ballet Mécanique'' (1923–24) is a Dadaist post-Cubist art film conceived, written, and co-directed by the artist Fernand Léger in collaboration with the filmmaker Dudley Murphy (with cinematographic input from Man Ray).Chilvers, Ian & Glav ...

'', Surrealism via the Metaphysical painting

Metaphysical painting ( it, pittura metafisica) or metaphysical art was a style of painting developed by the Italian artists Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. The movement began in 1910 with de Chirico, whose dreamlike works with sharp contras ...

of Georgio de Chirico, and fellow photographer Giuseppe Cavalli

Giuseppe Cavalli (29 November 1904 – 25 October 1961) was an Italian photographer, little known outside his native country. His work had a "simple, quiet aesthetic" and he was "best known for his ‘high-key’ style, characterised by the use of ...

with whom, convinced of the essential ‘uselessness’ of art, in 1947 he founded a group named ''La Bussola'' (The Compass). Influenced by Constructivist theories (and politically aligned with Communism), Veronesi used the cyanotype photogram after 1932 as a means of revealing metaphysical qualities in objects.

Late modern

In a 2008 essay A.D. Coleman perceived a return of the legacy Pictorialist methods being applied in art photography from 1976, a tendency represented inFrancesca Woodman

Francesca Stern Woodman (April 3, 1958 – January 19, 1981) was an American photographer best known for her black and white pictures featuring either herself or female models.

Many of her photographs show women, naked or clothed, blurred (due to ...

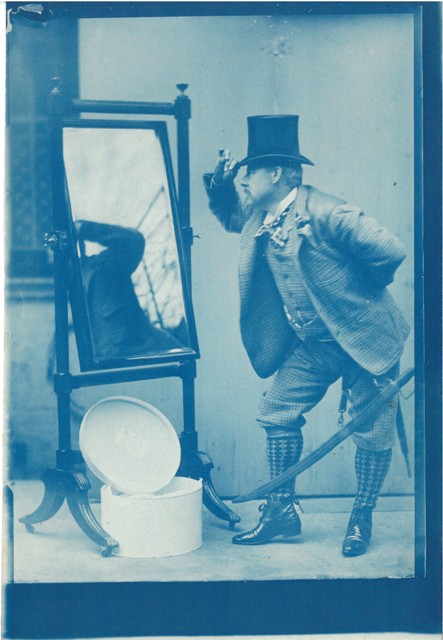

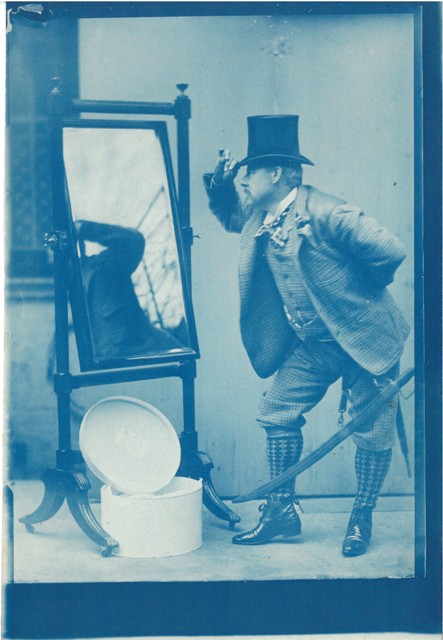

's late cyanotypes and in contact prints by Barbara Kasten and Bea Nettles. Weston Naef, curator of photography at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, in a 1998 ''New York Times'' article by critic Lyle Rexer, confirmed that "Looking back at hotography'spioneers, today's artists see a way to restore expression to an art beguiled by technology," referring to the loss of 'intimacy' in digital imaging to account for artists' attraction to daguerreotypes, tintypes, cyanotypes, stereopticon images, albumen prints, collodion wet plates; all physical and 'hands-on' methods. Artists David McDermott and Peter McGough, who met in the East Village New York art scene of the 1980s, and until 1995 took the phenomenon to the extreme of reconstructing themselves as Victorian gentlemen, adopting the lifestyle and documenting it and their possessions using vintage cameras and materials, first inspired by their discovery of the cyanotype, and dating their contemporary works in the nineteenth century.

Contemporary

Since 2000 around 10 books, and in growing numbers, are published each year in English in which 'cyanotype' appears in the title, compared to only 95 in total from 1843–1999. Though it has been an artform since its inception, the numbers of artists now employing the cyanotype process have burgeoned, and they are not solely photographers. In the book of the 2022 British exhibition ''Squaring the Circles of Confusion: Neo-Pictorialism in the 21st Century'' eight contemporary artists: Takashi Arai, Céline Bodin, Susan Derges, David George, Joy Gregory,

Since 2000 around 10 books, and in growing numbers, are published each year in English in which 'cyanotype' appears in the title, compared to only 95 in total from 1843–1999. Though it has been an artform since its inception, the numbers of artists now employing the cyanotype process have burgeoned, and they are not solely photographers. In the book of the 2022 British exhibition ''Squaring the Circles of Confusion: Neo-Pictorialism in the 21st Century'' eight contemporary artists: Takashi Arai, Céline Bodin, Susan Derges, David George, Joy Gregory, Tom Hunter

Sir Thomas Blane Hunter (born 6 May 1961) is a Scottish businessman, entrepreneur, and philanthropist.

Sports Division

Tom set up his first business after graduating from the University of Strathclyde as he was, in his own words, "unemployab ...

, Ian Phillips-McLaren and Spencer Rowell employ the craft of photography for postmodern purpose, including the cyanotype.

International

Many were included in the first American international survey of the cyanotype in 2016; the Worcester Art Museum’s ''Cyanotypes: Photography's Blue Period'' which displayed uses of the medium that extend well beyond the utilitarian contact-printing of negatives; Annie Lopez stitched together cyanotypes printed on tamale paper to create dresses; Brooke Williams tea-toned her cyanotypes, adjusting their color to accord with her story as a Jamaican American woman; and Hugh Scott-Douglas experimented with photograms and abstraction. In 2018, theNew York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second largest public library in the United States (behind the Library of Congress ...

exhibited the work of nineteen contemporary artists who employ the medium. Mounted 175 years after Anna Atkin's first book of cyanotypes, ''British Algae'', the exhibition was titled ''Anna Atkins Refracted: Contemporary Works''.

Amongst others currently working in, or with, cyanotype are;

America

Christian Marclay

Christian Marclay (born January 11, 1955) is a visual artist and composer. He holds both American and Swiss nationality.

Marclay's work explores connections between sound, noise, photography, video, and film. A pioneer of using gramophone records ...

who suggests musical scores in his grids of cassette tapes or their unspooling.

Kate Cordsen

Kate Cordsen (born 1966, Great Falls, Virginia, United States) is an American photographer and contemporary artist. Cordsen lives in New York City.

Education

She received a BA in the history of art and East Asian Studies from Washington and ...

applies Japanese aesthetics and non-Cartesian perspective in her mural-scale cyanotype landscapes.

Betty Hahn

Betty Hahn (born 1940) is an American photographer known for working in alternative and early photographic processes. She completed both her BFA (1963) and MFA (1966) at Indiana University. Initially, Hahn worked in other two-dimensional art mediu ...

was early to incorporate cyanotype with other art media including hand-painting with embroidery

Embroidery is the craft of decorating fabric or other materials using a needle to apply thread or yarn. Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as pearls, beads, quills, and sequins. In modern days, embroidery is usually seen on c ...

as a feminist statement

Meghann Riepenhoff reprises Anna Atkins by exposing her prepared papers underneath the waves, so light filters through moving sand, shells, and water currents.

Australia

Australian Todd McMillan draws on the Romantic idea of the sublime, and in his series ''Equivalents'' refers specifically to Alfred Steiglitz’ series of black and white imagery of that name produced between 1925 and 1934. McMillan chooses to use the cyanotype to produce images that one might mistake for full colour, but which actually renders both the sky and the clouds a monochrome blue tone.Canada

Canadian Erin Shirreff translates her sculptural interests into large-scale cyanotype photograms of temporary three-dimensional compositions in her studio with hours-long exposures during which component forms are moved, added or subtracted for transparent effect.Germany

German artist Marco Breuer abrades cyanotype prints on watercolour paper in representations of the passing of time. Likewise Katja Liebmann, also German, creates “etchings of time” by revisiting negatives to bring together yesterday and today, using cyanotype and other low tech painterly photographic processes, is able to “develop time like a picture” for “memories are malleable and recollection changes with time”.Iceland

Icelandic artist and filmmaker Inga Lísa Middleton employs the cyanotype for nostalgic representations of her homeland, and as a symbolic colour in imagery alerting audiences to an emerging catastrophe in the marine environment.Netherlands

Dutch artist Jan van Leeuwen was born in 1932. His self-portraits evoke the memory and trauma of Nazi occupation of Amsterdam during World War Two. He exposes sheets of silver-gelatin paper in a vintage portrait-studio view camera and they become the negatives for his cyanotypes.United Kingdom

British-born American residentWalead Beshty

Walead Beshty (born London, UK, 1976) is a Los Angeles-based artist and writer.

Beshty was an associate professor in the Graduate Art Department at Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, and has taught at numerous schools including University of ...

'Greece

Stefanos Tsakiris with his team, manage to print the largest cyanotype on cotton fabric. Approximately 70 people took poses on a 100meter long, as an evolution movement on coast of Thessaloniki. The final print managed to win the Guinness World Record, as the largest cyanotype.See also

*Blueprint

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets. Introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842, the process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number ...

* Sepia

Sepia may refer to:

Biology

* ''Sepia'' (genus), a genus of cuttlefish

Color

* Sepia (color), a reddish-brown color

* Sepia tone, a photography technique

Music

* ''Sepia'', a 2001 album by Coco Mbassi

* ''Sepia'' (album) by Yu Takahashi

* " ...

* Monochrome

A monochrome or monochromatic image, object or palette is composed of one color (or values of one color). Images using only shades of grey are called grayscale (typically digital) or black-and-white (typically analog). In physics, monochrom ...

* Film tinting

Film tinting is the process of adding color to black-and-white film, usually by means of soaking the film in dye and staining the film emulsion. The effect is that all of the light shining through is filtered, so that what would be white light bec ...

* Spirit duplicator

A spirit duplicator (also referred to as a Rexograph or Ditto machine in North America, Banda machine in the UK, Gestetner machine in Australia) is a printing method invented in 1923 by Wilhelm Ritzerfeld that was commonly used for much of the r ...

* Mimeograph

A mimeograph machine (often abbreviated to mimeo, sometimes called a stencil duplicator) is a low-cost duplicating machine that works by forcing ink through a stencil onto paper. The process is called mimeography, and a copy made by the pro ...

* Duotone

Duotone (sometimes also known as ''Duplex'') is a halftone reproduction of an image using the superimposition of one contrasting color halftone over another color halftone. This is most often used to bring out middle tones and highlights of an ...

References

Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

Mike Ware's New Cyanotype

– A new version of the cyanotype that address some of the classical cyanotype's shortcomings as a photographic process.

on AlternativePhotography.com * * {{Authority control Photographic processes dating from the 19th century Non-impact printing Alternative photographic processes History of photography