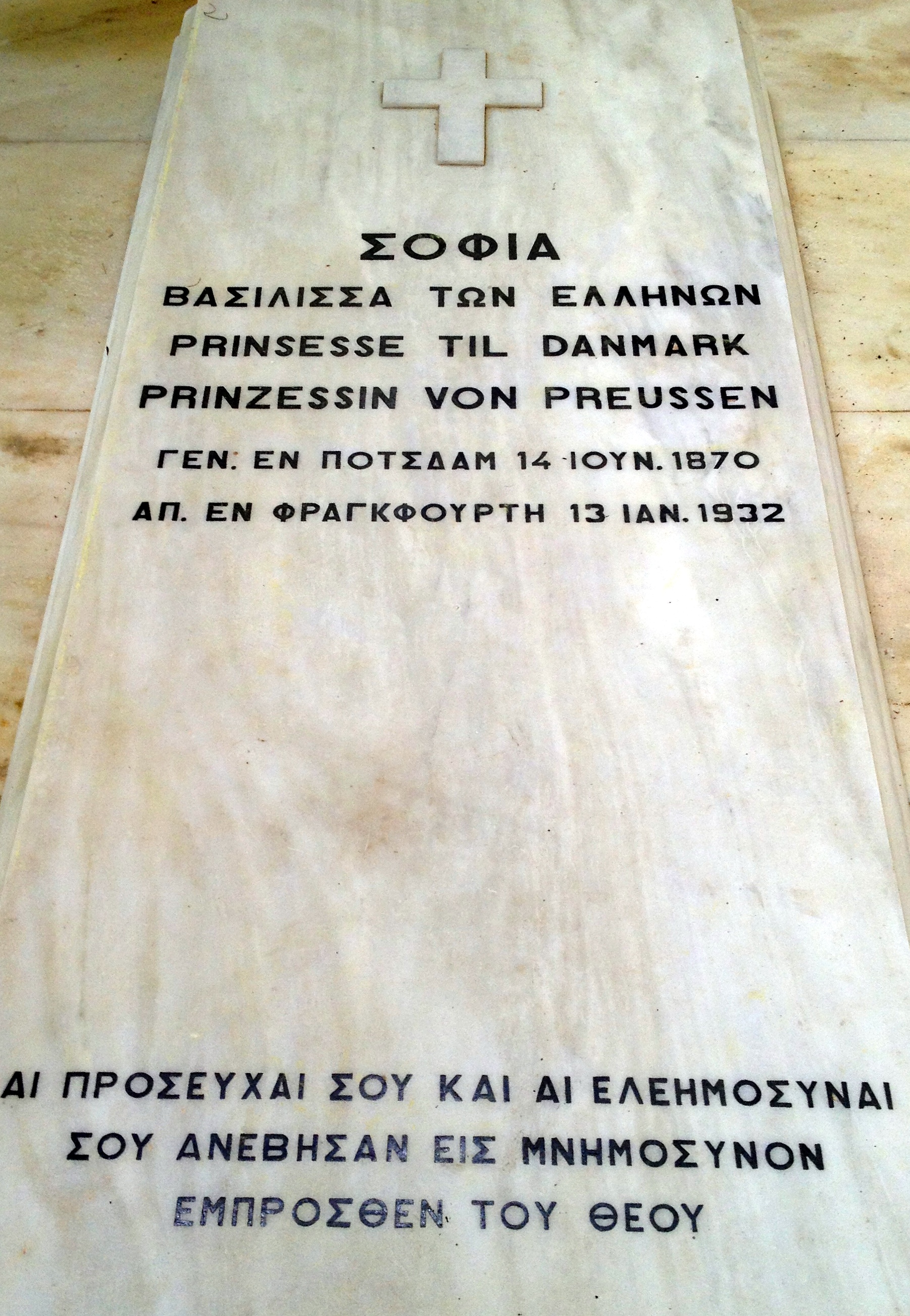

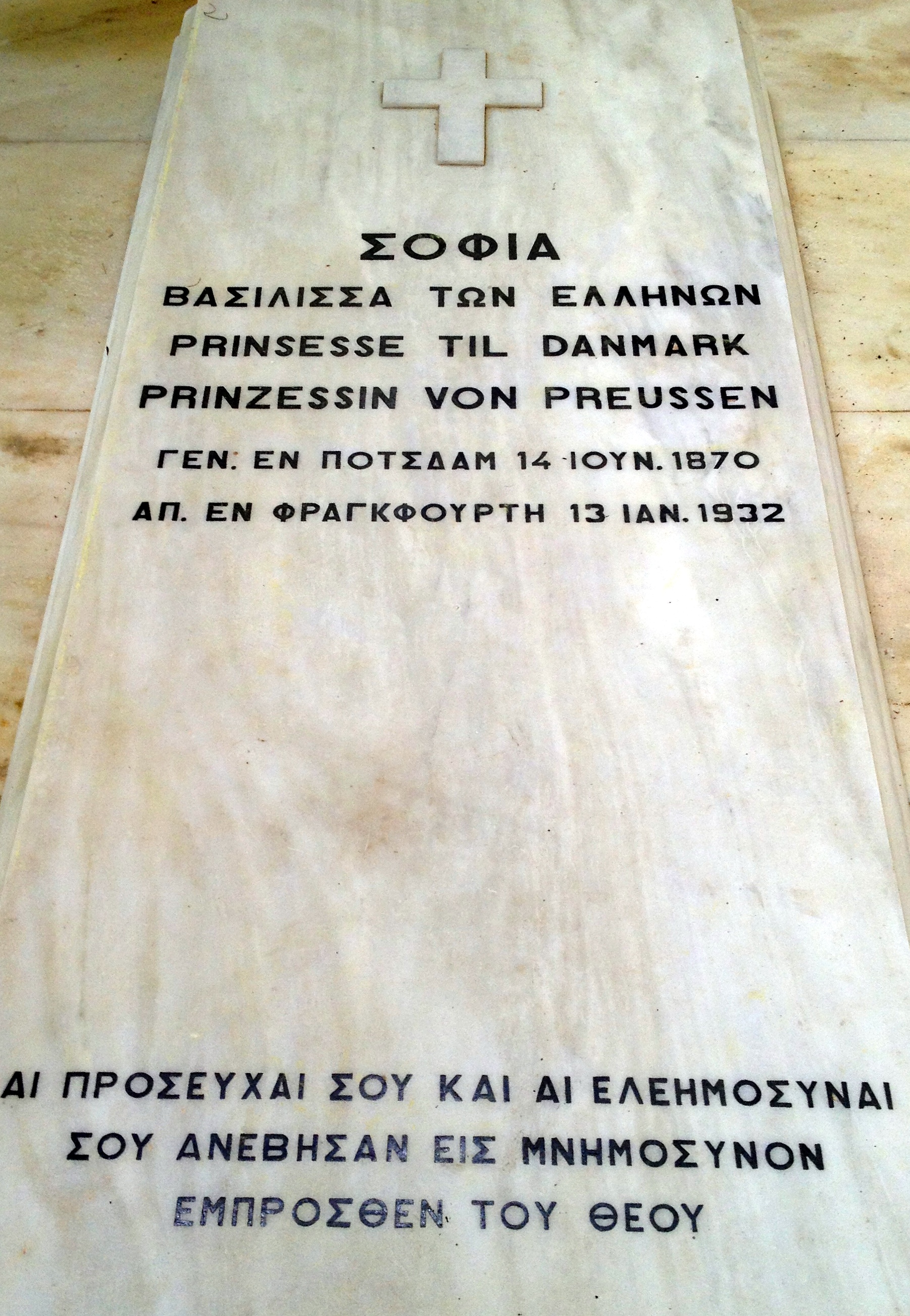

Sophia of Prussia (Sophie Dorothea Ulrike Alice, el, Σοφία; 14 June 1870 – 13 January 1932) was

Queen consort of the Hellenes

Consorts of the Kings of Greece were women married to the rulers of the Kingdom of Greece during their reign. All monarchs of modern Greece were male.The exception is King Otto, who was styled ''King of Greece''. Amalia, accordingly, is the only pe ...

from 1913–1917, and also from 1920–1922.

A member of the

House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenb ...

and child of

Frederick III, German Emperor

Frederick III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm Nikolaus Karl; 18 October 1831 – 15 June 1888), or Friedrich III, was German Emperor and King of Prussia for 99 days between March and June 1888, during the Year of the Three Emperors. Known informa ...

, Sophia received a liberal and

Anglophile

An Anglophile is a person who admires or loves England, its people, its culture, its language, and/or its various accents.

Etymology

The word is derived from the Latin word '' Anglii'' and Ancient Greek word φίλος ''philos'', meaning "frie ...

education, under the supervision of her mother

Victoria, Princess Royal

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of German Emperor Frederick III. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdo ...

. In 1889, less than a year after the death of her father, she married her third cousin

Constantine,

heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the Greek throne. After a difficult period of adaptation in her new country, Sophia gave birth to six children and became involved in the assistance to the poor, following in the footsteps of her mother-in-law,

Queen Olga. However, it was during the wars which Greece faced during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century that Sophia showed the most social activity: she founded

field hospital

A field hospital is a temporary hospital or mobile medical unit that takes care of casualties on-site before they can be safely transported to more permanent facilities. This term was initially used in military medicine (such as the Mobile Ar ...

s, oversaw the training of Greek nurses, and treated wounded soldiers.

However, Sophia was hardly rewarded for her actions, even after her grandmother

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

decorated her with the

Royal Red Cross

The Royal Red Cross (RRC) is a military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth for exceptional services in military nursing.

Foundation

The award was established on 27 April 1883 by Queen Victoria, with a single class of Memb ...

after the

Thirty Days' War: the Greeks criticized her links with Germany. Her brother Emperor

William II was indeed an ally of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and openly opposed the construction of the ''

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

'', which could establish a Greek state that would encompass all ethnic Greek-inhabited areas. During

World War I, the blood ties between Sophia and the German Emperor also aroused the suspicion of the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

, which criticized Constantine I for his neutrality in the conflict.

After imposing a blockade of Greece and supporting the rebel government of

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

, causing the

National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreign ...

, France and its allies deposed Constantine I in June 1917. Sophia and her family then went into exile in

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, while the second son of the royal couple replaced his father on the throne under the name of

Alexander I. At the same time, Greece entered the war alongside the Triple Entente, which allowed it to grow considerably.

After the outbreak of the

Greco-Turkish War in 1919 and the untimely death of Alexander I the following year, the

Venizelists abandoned power, allowing the royal family's return to Athens. However, the defeat of the

Greek army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

against the Turkish troops of

Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa ( ar, مصطفى

, Muṣṭafā) is one of the names of Prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Mou ...

forced Constantine I to abdicate in favor of his eldest son

George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089) ...

in 1922. Sophia and her family were then forced to a new exile, and settled in Italy, where Constantine died one year later, in 1923. With the proclamation of the Republic in Athens the following year, Sophia spent her last years alongside her family, before succumbing to cancer in Weimar Germany in early 1932 at the age of 61.

Life

Princess of Prussia and Germany

Birth in a difficult context

Princess Sophie was born in the

''Neues Palais'' in

Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and, with around 183,000 inhabitants, largest city of the German state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of ...

,

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was '' de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, on 14 June 1870. Her father,

Crown Prince Frederick William of Prussia, and her mother,

Victoria, Princess Royal

Victoria, Princess Royal (Victoria Adelaide Mary Louisa; 21 November 1840 – 5 August 1901) was German Empress and Queen of Prussia as the wife of German Emperor Frederick III. She was the eldest child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdo ...

of the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and Nor ...

(herself the eldest daughter of

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

and

Albert, Prince Consort) were already the parents of a large family and, as the penultimate child, Sophie was eleven years younger than her eldest brother, the future Emperor

William II of Germany. Frederick William and Victoria were a close couple, both on sentimental and political levels. Being staunch liberals, they lived away from the Berlin court and suffered the intrigues of a very conservative Chancellor

Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of ...

and members of the House of Hohenzollern.

A week after Sophie's birth, a case relating to succession to the throne of Spain damaged the Franco-Prussian relations. The tone between Paris and Berlin worsened even further after Bismarck published the humiliating

Ems Telegram on 13 July 1870. Six days later, the government of

Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

declared war on Prussia and the states of the

German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

offered support to Prussia, which then appeared as the victim of French imperialism. It was in this difficult context that Sophie was christened the following month, though all the men present were in uniform, as

France had declared war on Prussia. Sophie's mother described the event to Queen Victoria: "The Christening went off well, but was sad and serious; anxious faces and tearful eyes, and a gloom and foreshadowing of all the misery in store spread a cloud over the ceremony, which should have been one of gladness and thanksgiving".

However, the conflict lasted only a few months and even led to a brilliant German victory, leading to the proclamation of Sophie's grandfather King

William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

of Prussia as the first German Emperor on 18 January 1871.

Anglophile education

Sophie was known as "Sossy" during her childhood (the name was thought to have been picked because it rhymed with "Mossy", the nickname of her younger sister Margaret).

The children of the Crown Princely couple became grouped into two by age:

William

William is a male

Male (symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or ovum, in the process of fertilization.

A male organism cannot reproduce sex ...

,

Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

, and

Henry who were favored by their paternal grandparents, while

Viktoria, Sophie and

Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

were largely ignored by them. Sophie's two other brothers, Sigismund and Waldemar, died at a young age (Sigismund died before she was born, and Waldemar when he was 11 and she was 8); this drew the Crown Princess and her three younger daughters closer together, calling them "my three sweet girls" and "my trio".

The Crown Princess, believing in the superiority of all things

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, had her children's nurseries modeled on her childhood. Sophie was raised with a great love for England and all things associated with it as a result, and had frequent trips to visit her grandmother

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, whom she loved. Sophie often stayed in England for long periods, especially on the

Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

, where she liked to collect shells with her older siblings.

Because she was generally avoided by her paternal grandparents, Sophie's formative years were mainly shaped by her parents and her maternal grandmother Queen Victoria. As a little girl she was so deeply attached to the old British sovereign that the Crown Princess did not hesitate to leave her daughter for long periods under the care of her grandmother.

In Germany, Sophie largely stayed with her parents at two main residences: the ''

Kronprinzenpalais

The Kronprinzenpalais (English: ''Crown Prince's Palace'') is a former Royal Prussian residence on Unter den Linden boulevard in the historic centre of Berlin. It was built in 1663 and renovated in 1857 according to plans by Heinrich Strack in ...

'' in

Berlin, and the ''

Neues Palais

The New Palace (german: Neues Palais) is a palace situated on the western side of the Sanssouci park in Potsdam, Germany. The building was begun in 1763, after the end of the Seven Years' War, under King ''Friedrich II'' (Frederick the Great) and ...

'' in

Potsdam

Potsdam () is the capital and, with around 183,000 inhabitants, largest city of the German state of Brandenburg. It is part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. Potsdam sits on the River Havel, a tributary of the Elbe, downstream of ...

. Like her sisters

Viktoria and

Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

, she was particularly close to her parents and their relationship became even closer after the death, in 1879, of Waldemar, the favorite son of the Crown Princely couple.

Meeting and engagement with Constantine

In 1884,

Crown Prince Constantine of Greece ("Tino") was sixteen and his majority was declared by the government. He then received the title of

Duke of Sparta

Duke of Sparta (Katharevousa: , Demotic Greek: Δούκας της Σπάρτης) was a title instituted in 1868 to designate the Crown Prince of the Kingdom of Greece. Its legal status was exceptional, as the Constitution of Greece forbade the a ...

and ''Diadochos'' (διάδοχος / diádokhos, which means, "heir to the throne"). Soon after, the young man completed his military training in Germany, where he spent two full years in the company of a tutor, Dr. Lüders. He served in the Prussian Guard, took lessons of riding in

Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

and studied

Political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

at the

Universities of Heidelberg and

Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as we ...

.

After a long stay in England celebrating her grandmother's

Golden Jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali ''"স� ...

, Sophie became better acquainted with Constantine in the summer of 1887. The Queen watched their growing relationship, writing "Is there a chance of Sophie's marrying Tino? It would be very nice for her, for he is very good". The crown princess also hoped that Sophie would make a good marriage, considering her the most attractive among her daughters.

During his stay at the Hohenzollern court in

Berlin representing the Kingdom of Greece at the funeral of Emperor William I in March 1888, Constantine saw Sophie again. Quickly, the two fell in love and got officially engaged on 3 September 1888. However, their relationship was viewed with suspicion by Sophie's older brother William, by now the new Kaiser, and his wife

Augusta Victoria. This betrothal was not completely supported in the Hellenic royal family, either:

Queen Olga showed some reluctance to the projected union because Sophie was

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

and she would have preferred that the heir to the throne marry an

Orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

. Despite the difficulties, Tino and Sophie's wedding was scheduled for October 1889, in Athens.

Death of Emperor Frederick III

This period fell on an unhappy time for Sophie's family however, as her father

Emperor Frederick III was dying an agonizing death of

throat cancer

Head and neck cancer develops from tissues in the lip and oral cavity (mouth), larynx (throat), salivary glands, nose, sinuses or the skin of the face. The most common types of head and neck cancers occur in the lip, mouth, and larynx. Symptoms ...

. His wife and children kept vigil with him at the ''Neues Palais'', even celebrating Sophie's birthday and offering her a bouquet of flowers as a gift. The Emperor died the next day. Sophie's eldest brother William, now German Emperor, quickly ransacked his father's things in the hopes of finding "incriminating evidence" of "liberal plots". Knowing that her three youngest daughters were more dependent on her than ever for emotional support, the now-Dowager Empress Frederick remained close to them: "I have my three sweet girls - he loved so much - that are my consolation".

Already shocked by the attitude of her eldest son, the Dowager Empress was deeply saddened by Sophie's upcoming marriage and move to Athens. Nevertheless, she welcomed the happiness of her daughter and consoled herself in a voluminous correspondence with Sophie. Between 1889 and 1901, the two women exchanged no less than 2,000 letters. On several occasions, they were also found in each other's homes, in Athens and Kronberg. The preparations of Sophie's wedding were "hardly a surprising development considering the funeral atmosphere that prevailed at the home of her widowed mother".

Crown Princess of Greece

Auspicious marriage to the Greeks

On 27 October 1889, Sophie married Constantine in

Athens,

Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

in two religious ceremonies, one public and Orthodox and another private and Protestant. They were third cousins in descent from

Paul I of Russia

Paul I (russian: Па́вел I Петро́вич ; – ) was Emperor of Russia from 1796 until his assassination. Officially, he was the only son of Peter III and Catherine the Great, although Catherine hinted that he was fathered by her l ...

, and second cousins once removed through

Frederick William III of Prussia

Frederick William III (german: Friedrich Wilhelm III.; 3 August 1770 – 7 June 1840) was King of Prussia from 16 November 1797 until his death in 1840. He was concurrently Elector of Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire until 6 August 1806, wh ...

. Sophie's witnesses were her brother Henry and her cousins Princes

Albert Victor and

George of Wales; for Constantine's side, the witnesses were his brothers Princes

George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

and

Nicholas and his cousin the

Tsarevich of Russia.

The marriage (the first major international event held in Athens) was very popular among the Greeks. The names of the couple were reminiscent to the public of an old legend which suggested that when a King Constantine and a Queen Sophia ascended the Greek throne,

Constantinople the

Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia ( 'Holy Wisdom'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi), is a mosque and major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. The cathedral was originally built as a Greek Ortho ...

would fall to Greek hands. Immediately after the marriage of the ''Diadochos'', hopes arose for the Greek populace of the ''

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

'', i.e. the union of all Greeks in the same state. Abroad, the marriage of Constantine and Sophie raised much less enthusiasm. In France, it was feared that the arrival of a Prussian princess in Athens would switch the Kingdom of Greece to the side of the

Triple Alliance. In Berlin, the union was also unpopular: German interests were indeed important in the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

and the Emperor did not intend to help Greece simply because the ''Diadochos'' was his new brother-in-law.

Nevertheless, in Athens, the marriage ceremony was celebrated with pomp and gave rise to an especially significant

pyrotechnic

Pyrotechnics is the science and craft of creating such things as fireworks, safety matches, oxygen candles, explosive bolts and other fasteners, parts of automotive airbags, as well as gas-pressure blasting in mining, quarrying, and demolition. ...

spectacle on the

Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens, ...

and the Champ de Mars. Platforms were also built on the

Syntagma Square

Syntagma Square ( el, Πλατεία Συντάγματος, , "Constitution Square") is the central square of Athens. The square is named after the Constitution that Otto, the first King of Greece, was obliged to grant after a popular and militar ...

so the public could better admire the procession between the

Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Mas ...

and the

Cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominat ...

. The newlyweds were related to most of the European dynasties, so representatives of all the royal houses of the continent were part of the festivities:

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein- ...

(grandfather of the groom), Emperor

William II of Germany (brother of the bride), the

Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the ruler ...

(uncle of both groom and bride) and the Tsarevich of Russia (groom's cousin) were among the guests of honor. Naturally, Sophie's mother and sisters were also present at the ceremony.

In fact, the hosts and their retinues were so many in the small Hellenic Capital that George I could not receive all of them in his palace. He had to ask some members of the Greek high society to receive part of the guests in their mansions. Similarly, the sovereign was obliged to borrow the horses and carriages of his subjects in order to transport all visitors during the festivities. In addition, the king was forced to hastily buy dozens of additional

liveries for the lackeys at the service of the guests.

Installation in Athens

In Athens, Constantine and Sophia settled in a small villa of French style located on

Kifisias Avenue

Kifisias Avenue ( el, Λεωφόρος Κηφισίας) is one of the longest and busiest avenues in the Greater Athens area, Greece, containing the headquarters of many Greek and foreign companies and organizations.

Description

The total len ...

, while waiting for the Greek state to build a new home for them, the

Diadochos Palace, located near the Royal Palace. The couple also ordered the building of another house on the royal estate of

Tatoi because

King George I refused to allow work to be undertaken in the main palace. In Athens, Constantine and his wife lived a relatively simple life far removed from the protocol of other European courts but life in Greece was often monotonous and Sophia lamented for any company, save only for the wives of the tobacco sellers.

Sophia had difficulties adjusting to her new life. However, she took up learning

Modern Greek

Modern Greek (, , or , ''Kiní Neoellinikí Glóssa''), generally referred to by speakers simply as Greek (, ), refers collectively to the dialects of the Greek language spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the ...

(and managed to become almost perfectly fluent in a few years) and used her many trips abroad to furnish and decorate her new home. Less than nine months after her marriage, on 19 July 1890, the Crown Princess gave birth to her first child, a slightly premature son who was named

George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

after his paternal grandfather, but the birth went wrong and the

umbilical cord

In placental mammals, the umbilical cord (also called the navel string, birth cord or ''funiculus umbilicalis'') is a conduit between the developing embryo or fetus and the placenta. During prenatal development, the umbilical cord is physiologi ...

was wrapped around the baby's neck, almost choking him. Fortunately for the mother and child, the German midwife sent by the Dowager Empress Victoria to help her daughter in childbirth managed to resolve the situation and no tragic consequences occurred.

Conversion to Orthodoxy

After the birth of her eldest son, Sophia decided to embrace the faith of her subjects and convert to the

Orthodox faith. Having requested and received the blessing of her

mother

]

A mother is the female parent of a child. A woman may be considered a mother by virtue of having given birth, by raising a child who may or may not be her biological offspring, or by supplying her ovum for fertilisation in the case of gestati ...

and

Queen Victoria, grandmother, the Crown Princess informed her in-laws of her intention and asked Queen

Olga for instruction in orthodoxy. The Greek royal family was delighted by the news, because the announcement of the conversion would be popular among the Greeks but

George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria (fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dol ...

insisted that Germanus II,

Metropolitan of Athens and

Head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may not ...

of the

Autocephalous

Autocephaly (; from el, αὐτοκεφαλία, meaning "property of being self-headed") is the status of a hierarchical Christian church whose head bishop does not report to any higher-ranking bishop. The term is primarily used in Eastern Ort ...

Greek Church, would instruct Sophie in the Orthodoxy, rather than his wife. Of Russian origin, Queen Olga was indeed considered by some

Greek nationalists

Greek nationalism (or Hellenic nationalism) refers to the nationalism of Greeks and Greek culture.. As an ideology, Greek nationalism originated and evolved in pre-modern times. It became a major political movement beginning in the 18th century, ...

as an "agent of the

Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement which crystallized in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with the advancement of integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had rule ...

" and George I therefore preferred that Germanus II would guarantee the task that could otherwise create difficulties for the Crown.

Though the news of her conversion was greeted calmly by most members of her family, Sophia feared the reaction of Emperor William II, who took his status as Head of the

Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces

The Prussian Union of Churches (known under multiple other names) was a major Protestant church body which emerged in 1817 from a series of decrees by Frederick William III of Prussia that united both Lutheran and Reformed denominations in Pru ...

very seriously and hated disobedience more than anything.

Sophia took a trip to Germany with her husband for the occasion of the wedding of her sister Viktoria to

Prince Adolf of Schaumburg-Lippe

Prince Adolf of Schaumburg-Lippe (german: Adolf Wilhelm Viktor; 20 July 1859 – 9 July 1916) was a German prince of the House of Schaumburg-Lippe and a Prussian General of the Cavalry. He was regent of the Principality of Lippe from 1895 ...

, in November 1890, and personally announced to her brother her intentions to change her religion. As expected, the news strongly displeased the Emperor and his wife, the very pious Empress

Augusta Victoria. The latter even tried to dissuade her sister-in-law to convert, triggering a heated argument between the two women. The Empress later claimed that this caused her to go into premature labor, and deliver her sixth child,

Prince Joachim, too early. William II, meanwhile, was so angry that he threatened Sophia with excluding her from the Prussian royal family. Pressed by her mother to appear conciliatory, Sophia ended up writing a letter to her brother explaining the reasons for her conversion but the Emperor would not listen, and for three years he forbade his sister to enter Germany. Upon receiving his reply Sophie sent a telegram to her mother: "Received answer. Keeps to what he said in Berlin. Fixes it to three years. Mad. Never mind."

Sophia officially converted on 2 May 1891; however, the imperial sentence was ultimately never implemented. Nevertheless, relations between William II and his sister were permanently marked by Sophia's decision. Indeed, the Emperor was an extremely resentful man and he never stopped making his younger sister pay for her disobedience.

Social work

Throughout her life in Greece, Sophia was actively involved in social work and helping the underprivileged. Following in the footsteps of Queen Olga, she led various initiatives in the field of education,

soup kitchen

A soup kitchen, food kitchen, or meal center, is a place where food is offered to the hungry usually for free or sometimes at a below-market price (such as via coin donations upon visiting). Frequently located in lower-income neighborhoods, sou ...

s and development of hospitals and orphanages. In 1896, the Crown Princess also founded the Union of Greek Women, a particularly active organization in the field of assistance to refugees from the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Fascinated by

arboriculture

Arboriculture () is the cultivation, management, and study of individual trees, shrubs, vines, and other perennial woody plants. The science of arboriculture studies how these plants grow and respond to cultural practices and to their environmen ...

and concerned by the fires that regularly ravaged the country, Sophia was also interested in the

reforestation

Reforestation (occasionally, reafforestation) is the natural or intentional restocking of existing forests and woodlands (forestation) that have been depleted, usually through deforestation, but also after clearcutting.

Management

A debate ...

. In addition, she was one of the founders of the Greek Animal Protection Society.

However, it was during wartime that Sophie showed the most resilience. In 1897, when the

Thirty Days' War broke out, Sophia and other female members of the royal family actively worked with the Greek Red Cross in order to help wounded soldiers. On the

Thessalian

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thess ...

front, the Crown Princess founded

field hospitals, visited the wounded and even directly administered care for victims of the fighting. Sophia also facilitated the arrival of English nurses in Greece and even participated in the training of young women volunteers to provide assistance to wounded soldiers.

The involvement of Sophia and her mother-in-law in the aid to the victims of fighting (either of Greek or Turkish origin) was so active that it elicited admiration from other European courts. As a reward for their work, both women were decorated with the

Royal Red Cross

The Royal Red Cross (RRC) is a military decoration awarded in the United Kingdom and Commonwealth for exceptional services in military nursing.

Foundation

The award was established on 27 April 1883 by Queen Victoria, with a single class of Memb ...

by

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

, in December 1897. Unfortunately for the Crown Princess, her help for the wounded soldiers was less appreciated in Greece, where the population blamed the royal family, and especially ''Diadochos'' Constantine, for the loss against the Ottomans.

Consequences of the War of Thirty Days

After the Thirty Days' War, a powerful anti-monarchical movement developed in Greece and Sophia herself was not immune to criticism. Always eager to punish his sister for her disobedience, Emperor William II of Germany openly supported the Ottoman Empire during the conflict and agreed to offer his

mediation

Mediation is a structured, interactive process where an impartial third party neutral assists disputing parties in resolving conflict through the use of specialized communication and negotiation techniques. All participants in mediation are ...

after being begged by his sister, his mother and his grandmother. He demanded that Greece agree to humiliating conditions in exchange for his intervention and the population believed that he did so with the consent of his sister.

However Sophia was not the only victim of popular condemnation. In fact, it was openly discussed in Athens that the ''Diadochos'' should be sent before a military court to punish him for the national defeat and depose George I as was previously done with his predecessor

Otto I

Otto I (23 November 912 – 7 May 973), traditionally known as Otto the Great (german: Otto der Große, it, Ottone il Grande), was East Frankish king from 936 and Holy Roman Emperor from 962 until his death in 973. He was the oldest son of Hen ...

. Several weeks after the signing of the Peace Treaty between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, the situation became so tense that the sovereign was a subject of an assassination attempt when he traveled in an open carriage with his daughter,

Princess Maria, but George I defended himself so bravely that he recovered at least some estimation from his subjects.

In these difficult conditions, Constantine and Sophia choose to live some time abroad. In 1898, they were established in

Kronberg

Kronberg im Taunus is a town in the Hochtaunuskreis district, Hesse, Germany and part of the Frankfurt Rhein-Main urban area. Before 1866, it was in the Duchy of Nassau; in that year the whole Duchy was absorbed into Prussia. Kronberg lies at t ...

, and then in

Berlin. There the ''Diadochos'' resumed his military training with General

Colmar von der Goltz

Wilhelm Leopold Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz (12 August 1843 – 19 April 1916), also known as ''Goltz Pasha'', was a Prussian Field Marshal and military writer.

Military career

Goltz was born in , East Prussia (later renamed Goltzhausen; now ...

and for a year, he received the command of a Prussian division. To mark their reconciliation, Emperor William II also appointed Sophia as Honorary Commander of the 3rd regiment of the Imperial Guard.

The couple returned to Greece in 1899 and the government of

Georgios Theotokis

Georgios Theotokis ( el, Γεώργιος Θεοτόκης, 1844 in Corfu – 12 January 1916 in Athens) was a Greek politician and Prime Minister of Greece, serving the post four times. He represented the Modernist Party or ''Neoteristikon Ko ...

appointed Constantine as the head of the Hellenic Staff. This promotion, however, caused some controversy among the army, which still considered the ''Diadochos'' as the main person responsible for the defeat in 1897.

Family deaths

Back in Greece with her husband, the Crown Princess resumed her charity work. However, the health of both her mother and English grandmother deeply concerned her. The Empress Dowager of Germany was indeed suffering from

breast cancer

Breast cancer is cancer that develops from breast tissue. Signs of breast cancer may include a lump in the breast, a change in breast shape, dimpling of the skin, milk rejection, fluid coming from the nipple, a newly inverted nipple, or a r ...

, which caused her extreme suffering. As for the Queen of the United Kingdom, she was approaching the age of eighty and her family knew that the end was close but the last years of her reign were marked by the

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, during which the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and Nor ...

suffered terrible losses facing the

Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a South African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers first arriving at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th and 18th centuries.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casti ...

resistance. Sophia was concerned that the difficulties suffered by the British in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

would undermine the already fragile health of her grandmother.

Queen Victoria finally died of a

cerebral hemorrhage

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), also known as cerebral bleed, intraparenchymal bleed, and hemorrhagic stroke, or haemorrhagic stroke, is a sudden bleeding into the tissues of the brain, into its ventricles, or into both. It is one kind of bleed ...

on 22 January 1901 in

Osborne House

Osborne House is a former royal residence in East Cowes, Isle of Wight, United Kingdom. The house was built between 1845 and 1851 for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert as a summer home and rural retreat. Albert designed the house himself, in t ...

. Very affected by the death of the sovereign, Sophia traveled to the United Kingdom for her funeral and attended a religious ceremony in her honor in Athens with the rest of the Greek royal family.

A few months later, in the summer of 1901, Sophie went to ''Friedrichshof'' to look after her mother, whose health continued to decline. Five months pregnant, the Crown Princess knew that the Dowager Empress was dying and, with her sisters Viktoria and Margaret, she accompanied her until her last breath on 5 August. In the space of seven months Sophia lost two of her closest relatives. However, her new maternity helped keep her from feeling sorry for herself.

Goudi coup and its consequences

In Greece, political life remained volatile throughout the first years of the 20th century and the ''

Megali Idea

The Megali Idea ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα, Megáli Idéa, Great Idea) is a nationalist and irredentist concept that expresses the goal of reviving the Byzantine Empire, by establishing a Greek state, which would include the large Greek popul ...

'' ( el, Μεγάλη Ιδέα ''Megáli Idéa'', "Great Idea") continued to be a central concern of the population. In 1908, the

Cretan

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, an ...

authorities unilaterally proclaimed the attachment of their island to the Kingdom of Greece but for fear of Turkish reprisals, the Greek government refused to recognize the annexation. In Athens, the pusillanimity of the King and government was shocking, particularly to the military. On 15 August 1909, a group of officers gathered in the "Military League" ( el, Στρατιωτικός Σύνδεσμος, Stratioticos Syndesmos) and organized the so-called

Goudi coup. While declaring to be monarchists, members of the League, led by

Nikolaos Zorbas, asked, among other things, for the sovereign to expel his son from the army. Officially, this was to protect the Crown Prince from the jealousies that could arise from his friendship with some soldiers but the reality was quite different: officers continued to hold the ''Diadochos'' responsible for the 1897 defeat.

The situation became so tense that George I's sons had to resign from their military posts to save their father the shame of having to expelled them. In September, the ''Diadochos'', his wife and their children also chose to leave Greece and seek refuge in Germany at

Friedrichshof, now owned by the

Princess Margaret of Prussia. Meanwhile, in Athens, discussions began about dethroning the

House of Glücksburg

The House of Glücksburg (also spelled ''Glücksborg'' or ''Lyksborg''), shortened from House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, is a collateral branch of the German House of Oldenburg, members of which have reigned at various tim ...

to establishing a republic or replacing the sovereign with either a bastard son of Otto I, a foreign prince or with Prince

George

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd Presiden ...

, with Sophia as

regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

.

In December 1909, Colonel Zorbas, head of the Military League, pressured George I to appoint him as the head of the government in place of Prime Minister

Kyriakoulis Mavromichalis

Kyriakoulis Petrou Mavromichalis (, 1850–1916) was a Greek politician of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who briefly served as the 30th Prime Minister of Greece.

Mavromichalis was born in Athens in 1850 into the renowned Mavromichali ...

. The sovereign refused but the government underwent reforms which favored the military. The staff was reorganized and supporters of the ''Diadochos'', including

Ioannis Metaxas

Ioannis Metaxas (; el, Ιωάννης Μεταξάς; 12th April 187129th January 1941) was a Greek military officer and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 1936 until his death in 1941. He governed constitutionally for t ...

, were expelled. At the same time, a French army mission was called to reorganize the Greek army, which threatened both Sophia and her husband, as they helped develop republican ideas within the military.

Despite these reforms, some members of the Military League continued to oppose the government in order to take power. They then traveled to

Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cypru ...

to meet the government head of the island,

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

, and offered him the post of

Prime Minister of Greece

The prime minister of the Hellenic Republic ( el, Πρωθυπουργός της Ελληνικής Δημοκρατίας, Prothypourgós tis Ellinikís Dimokratías), colloquially referred to as the prime minister of Greece ( el, Πρωθυ� ...

. However the Cretan leader did not want to appear in Greece to be supported by the army and convinced them to arrange for new elections. In March 1910, the king eventually called for elections and Venizelos and his supporters came to power. For the royal family, this was a difficult time.

However, Venizelos did not want to weaken the Crown. To show that he did not obey the army, he restored the members of the royal family to their military duties and the ''Diadochos'' thus again became Chief of the Staff. Back in Greece on 21 October 1910, after over a year of exile, Sophia nevertheless remained very suspicious of the new government and the militia. She refused any contact with Venizelos, blaming him as partly responsible for the humiliation suffered by the royal family. The Princess also had problems with her father-in-law, whom she accused of having been weak during the crisis.

Nurse during the First Balkan War

After the arrival of Venizelos in power, the

Greek army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

was modernized and equipped with the support of French and British officers. New warships were also controlled by the Navy. The aim of the modernization was to make the country ready for a new war against the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

but to defeat the enemy and achieve the ''Megali Idea'', Greece needed allies. That was why, under the Prime Minister, Greece signed alliances with its neighbors and participated in the creation of the

Balkan League

The League of the Balkans was a quadruple alliance formed by a series of bilateral treaties concluded in 1912 between the Eastern Orthodox kingdoms of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and directed against the Ottoman Empire, which at the ...

in June 1912. Thus, when

Montenegro

)

, image_map = Europe-Montenegro.svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Podgorica

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, official_languages = M ...

declared war on the Ottoman Empire on 8 October 1912, they were joined less than ten days later by

Serbia,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Maced ...

and Greece. This was the beginning of the

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

.

While the ''Diadochos'' and his brothers took command of Greek troops, Queen Olga, Sophia, and her sisters-in-law (

Marie Bonaparte

Princess Marie Bonaparte (2 July 1882 – 21 September 1962), known as Princess George of Greece and Denmark upon her marriage, was a French author and psychoanalyst, closely linked with Sigmund Freud. Her wealth contributed to the popularity o ...

,

Elena Vladimirovna of Russia and

Alice of Battenberg) took in charge the aid to wounded soldiers and refugees. In one month, the princesses collected 80,000 garments for the military and gathered around them doctors, nurses and medical equipment. The Queen and Crown Princess also opened a public subscription in order to create new hospitals in Athens and on the front.

[Captain Walter Christmas: ''King George of Greece'', New York, New York, MacBride, Naste & Company, 1914, p. 368.] Very active, the princesses did not just stay in the back but also went to the center of the military operations. Queen Olga and Sophia visited

Larissa and

Elassona

Elassona ( el, Ελασσόνα; Katharevousa: gr, Ἐλασσών, Elasson) is a town and a municipality in the Larissa regional unit in Greece. During antiquity Elassona was called Oloosson (Ὀλοοσσών) and was a town of the Perrhaebi t ...

, while Alice made long stays in

Epirus

sq, Epiri rup, Epiru

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = Historical region

, image_map = Epirus antiquus tabula.jpg

, map_alt =

, map_caption = Map of ancient Epirus by Heinric ...

and

Macedonia. Meanwhile, Elena directed an ambulance-train and Marie Bonaparte set up a

hospital ship

A hospital ship is a ship designated for primary function as a floating medical treatment facility or hospital. Most are operated by the military forces (mostly navies) of various countries, as they are intended to be used in or near war zones. In ...

that connected

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

to the capital.

The war was an opportunity for the princesses to prove themselves useful to their adopted country but it also exacerbated rivalries within the royal family. Conflict began due to Sophia's jealousy of her cousin and sister-in-law Alice. In fact, a heated argument between the two young women erupted after Alice sent, without requesting permission from Sophia, nurses dependent on the Crown Princess to Thessaloniki. One seemingly innocuous event provoked a real discomfort within the family and Queen Olga was shocked when Sophia's attitude was supported by her husband.

Marital problems and private life

Sophia and Constantine's marriage was harmonious during the first years. However, faithfulness was not the greatest quality of the ''Diadochos'' and his wife soon had to deal with his numerous extramarital affairs. Initially shocked by his betrayal, Sophia soon followed the example of her mother-in-law and condoned the behavior of her husband. From 1912, however, the couple became noticeably separated. At that time, Constantine began an affair with Countess Paola von Ostheim (''née'' Wanda Paola Lottero), an

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional It ...

stage actress who had recently divorced from

Prince Hermann of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

; this relationship lasted until Constantine's death.

When Sophia gave birth to her sixth and last child, a daughter named

Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Chri ...

on 4 May 1913, a persistent gossip stated that the child was the result of her own affairs. The rumors, true or false, did not affect Constantine, who easily recognized his paternity.

In private, the Crown Princely couple communicated in English and it was mainly in this language that they raised their children, who grew up in a loving and warm atmosphere in the middle of a cohort of tutors and British nannies. Like her mother, Sophia inculcated in her offspring the love for the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and Nor ...

and for several weeks every year, the family spent time in Great Britain, where she visited the beaches of

Seaford and

Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the lar ...

. However, the summer vacations of the family were spent not only in

''Friedrichshof'' with the

Empress Dowager

Empress dowager (also dowager empress or empress mother) () is the English language translation of the title given to the mother or widow of a Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese emperor in the Chinese cultural sphere.

The title was a ...

, but also in

Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek islands, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of G ...

and

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

, where the Greek royal family went aboard the yacht ''Amphitrite''.

Queen of the Hellenes: 1st tenure

Assassination of George I and Second Balkan War

The First Balkan War ended in 1913 with the defeat of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

by the Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian and Montenegrin coalition. The Kingdom of Greece was greatly expanded after the conflict but disagreements soon arose between the Allied powers: Greece and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Maced ...

competed for possession of

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

and its surrounding region.

To affirm the sovereignty of the Greeks over the main city of

Macedonia, George I moved to the city soon after its conquest by the ''Diadochos'', on 8 December 1912. During his long stay in the city, the King went out every day to walk unescorted in the streets, as he had become accustomed to doing in Athens. On 18 March 1913 a Greek anarchist named

Alexandros Schinas shot him in the back from a distance of two paces while he was walking in

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

near the

White Tower.

Sophia was in Athens when she learned of the murder of her father-in-law, the king. Now, as

Queen Consort of the Hellenes

Consorts of the Kings of Greece were women married to the rulers of the Kingdom of Greece during their reign. All monarchs of modern Greece were male.The exception is King Otto, who was styled ''King of Greece''. Amalia, accordingly, is the only pe ...

, the responsibility fell upon her to break the news of the murder to her mother-in-law. Together with her eldest daughter,

Princess Helen, both comforted the now Dowager Queen, who received the news stoically. The next day, members of the royal family who were present in the capital went to Thessaloniki. Arriving in the Macedonian city, they visited the scene of the murder and collected the remains of the King to escort them back to Athens, where he was buried at

Tatoi.

In this difficult context, the death of George I sealed the possession of Thessaloniki to Greece. Still, the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

broke out in June 1913 over the division of Macedonia between the former allies of the first conflict. Victorious again, Greece came out of this war considerably enlarged, with the prestige of King Constantine I and Queen Sophia also increased.

Private life

After their accession to the throne, Constantine and Sophia continued to lead the simple lifestyle that they had enjoyed during their time as heirs. They spent their free time practising

botany

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek w ...

, which was their common passion, and transformed the gardens of the

New Royal Palace on the

English model.

The couple was very close to other members of the royal family, especially Prince

Nicholas. Every Tuesday, the King and Queen dined with him and his wife Elena, and on Thursdays, they returned the visit with the royal couple at the Royal Palace.

Outbreak of World War I

At the outbreak of

World War I on 4 August 1914 Sophia was in England at

Eastbourne

Eastbourne () is a town and seaside resort in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, east of Brighton and south of London. Eastbourne is immediately east of Beachy Head, the highest chalk sea cliff in Great Britain and part of the lar ...

with several of her children while her husband and their daughter Helen were the only representatives of the dynasty still present in Athens. However, given the gravity of the events, the Queen quickly returned to Greece, where she was soon joined by the rest of the royal family.

While the greater European states entered into the conflict one by one, Greece officially proclaimed its

neutrality. Being grandchildren of the so-called "

Father-in-law

A parent-in-law is a person who has a legal affinity with another by being the parent of the other's spouse. Many cultures and legal systems impose duties and responsibilities on persons connected by this relationship. A person is a child-in-law ...

and

Grandmother of Europe" (as

Christian IX of Denmark

Christian IX (8 April 181829 January 1906) was King of Denmark from 1863 until his death in 1906. From 1863 to 1864, he was concurrently Duke of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg.

A younger son of Frederick William, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein- ...

and

Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

respectively were known), Constantine and Sophia were closely related to the monarchs of the

Triple Alliance and the

Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French '' entente'' meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as well a ...

. Above all, the King and Queen were aware that Greece was already weakened by the

Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

and was not ready to participate in a new conflict. However, the population did not share the opinion of the sovereigns. Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, whose great diplomatic skills had been greatly acknowledged at the

London Conference of 1912-1913, especially by

David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

and

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

, knew that Greece's newly acquired dominions were in a precarious state, so Greece had to participate in the war with the

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale (; ) comprised a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic which saw a significant improvement in Anglo-French relations. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial de ...

in order to safeguard its winnings from the

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

. Moreover, the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Maced ...

and even

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

had aligned themselves with Germany and, if Germany won the war, it would most certainly be at Greece's expense, given that Bulgaria's and the Ottoman Empire's winnings in land would inevitably come from Greek lands acquired in 1913, since both countries, greatly angered at the loss of

Macedonia, were looking to overthrow the

Treaty of Bucharest. Indeed, the country was in a dire state, led by a weak Germanophile King and his manipulative Queen to destruction and civil war.

Things got complicated when the Triple Entente engaged in the

Gallipoli Campaign in February 1915. Wanting to release the Greek populations of

Asia Minor

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

from Ottoman rule, Constantine I was at first ready to offer his support to the Allies and bring his country into the war. However, the King faced the opposition of his Staff and, in particular, Ioannis Metaxas, who threatened to resign if Greece entered the war. The country did not have the means, even though the Allies offered great advantages for Greece in return for its participation. Constantine I was a great Germanophile; he had been educated in Germany, almost been raised as a German and admired immensely the

Kaiser

''Kaiser'' is the German word for " emperor" (female Kaiserin). In general, the German title in principle applies to rulers anywhere in the world above the rank of king (''König''). In English, the (untranslated) word ''Kaiser'' is mainly a ...

, who was his brother-in-law. The King had no particular desire to bring the country into war, and so he became a staunch supporter of neutrality. Constantine I therefore desisted, causing the wrath of Venizelos, who saw his country being in great peril because of the King. Because of Constantine I's manifestly unconstitutional actions, the Prime Minister handed over his resignation in 1915 (even after he won twice the elections held on the subject of war). A royal government then emerged, however

Eleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

was proven right on 25 May 1916, when the royal Greek government of Athens permitted the surrender of the

Fort Roupel to the Germans and their Bulgarian allies as a counterbalance to the Allied forces that had been established in Thessaloniki. The German-Bulgarian troops then proceeded to

occupy most of eastern

Macedonia without resistance, resulting in the massacre of the Greek population there. This act led to the outbreak of a revolt of

Venizelist

Venizelism ( el, Βενιζελισμός) was one of the major political movements in Greece from the 1900s until the mid-1970s.

Main ideas

Named after Eleftherios Venizelos, the key characteristics of Venizelism were:

*Greek irredentism: T ...

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

officers in

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

and the establishment of the

Provisional Government of National Defence

The Provisional Government of National Defence (), also known as the State of Thessaloniki (Κράτος της Θεσσαλονίκης), was a parallel administration, set up in the city of Thessaloniki by former Prime Minister Eleftherios Ven ...

under

Entente auspices there, opposed to the official government of Athens and

Constantine I

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterrane ...

, cementing the so-called "

National Schism

The National Schism ( el, Εθνικός Διχασμός, Ethnikós Dichasmós), also sometimes called The Great Division, was a series of disagreements between King Constantine I and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos regarding the foreign ...

".

Weakened by all these events, Constantine I became seriously ill after this crisis. Suffering from

pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

aggravated by a

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severit ...

, he remained in bed for several weeks and nearly died. In Greece, public opinion was outraged by a rumour, spread by Venizelists, who said that the King was not sick but was in fact wounded with a knife by Sophia during an argument where she wanted to force him to go to war alongside her brother. Certainly the Queen kept a frequent communication with her brother. In the words of G. Leon, "She remained a German, and Germany's interests were placed above those of her adopted country which meant little to her. Actually she never had any sympathy for the Greek people". The Queen was also suspected to be the ''power behind the throne'', given Constantine's gradual physical collapse and habitual apathy and irresolution: various sources from Greece from that period (even Royalist sources, whose diaries, journals and extensive correspondence have been a subject of great study in Greece) mention that Sophia used to hide behind a curtain in her husband's apartments during Cabinet meetings and private audiences with the King, in order to be informed on the state of affairs, a continued situation which served to alienate herself more and more from Greek populace.

The King's health declined so a ship was sent to the Island of

Tinos in order to seek the miraculous icon of the Annunciation who supposedly heal the sick. While Constantine I had already received the

last sacraments, he partly recovered his health after kissing the icon. However, his situation remained worrying and he needed surgery before he could resume his duties. Relieved by the recovery of her husband, Sophia offered then, by way of

ex-voto

An ex-voto is a votive offering to a saint or to a divinity; the term is usually restricted to Christian examples. It is given in fulfillment of a vow (hence the Latin term, short for ''ex voto suscepto'', "from the vow made") or in gratitude o ...

, a

sapphire

Sapphire is a precious gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum, consisting of aluminium oxide () with trace amounts of elements such as iron, titanium, chromium, vanadium, or magnesium. The name sapphire is derived via the Latin "sapphi ...

to enrich the icon.

During the King's illness period, the Triple Entente continued to put pressure on Greece to go to war alongside them.

Dimitrios Gounaris

Dimitrios Gounaris (; 5 January 1867 – 28 November 1922) was a Greek politician who served as the Prime Minister of Greece from 25 February to 10 August 1915 and 26 March 1921 to 3 May 1922. Leader of the People's Party, he was the main ri ...

, successor of Venizelos as Prime Minister, proposed the intervention of his country in the conflict in exchange for the protection of the Allies against an eventual attack of

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Maced ...

. However, the Triple Entente, although eager to form an alliance with them, refused the agreement.

Rupture with Venizelos

In June 1915, legislative elections gave victory to the Venizelists. A month later, Constantine I, still convalescent, reassumed his official duties and eventually called on Venizelos to head the Cabinet on 16 August. In September, Bulgaria entered the war alongside the

Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

and attacked

Serbia, ally of Greece since 1913. Venizelos asked the King to proclaim a general mobilization, which he refused. However, to avoid a new political crisis, Constantine I finally proclaimed mobilization while making it clear that this was a purely defensive measure. On 3 October, in order to force the King to react, the Prime Minister called on the

Allied Powers to occupy the port of

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of ...

but Constantine I left the city when the

French, Italian and British forces landed in the city. The break was now final between Venizelos and the royal family.