Cristopher Columbus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, CristÃģbal ColÃģn

* pt, CristÃģvÃĢo Colombo

* ca, CristÃēfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was an Italian explorer and navigator who completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean sponsored by the

Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the

Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the  Being ambitious, Columbus eventually learned

Being ambitious, Columbus eventually learned

Under the

Under the

Three

Three

By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King

By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King

Between 1492 and 1504, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the

Between 1492 and 1504, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from

Catholic Monarchs of Spain

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of TrastÃĄmara and were second cousins, being both ...

, opening the way for the widespread European exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

and colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although Norse colonization of North America, the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizin ...

. His expeditions were the first known European contact with the Caribbean, Central America, and South America.

The name ''Christopher Columbus'' is the anglicisation

Anglicisation is the process by which a place or person becomes influenced by English culture or British culture, or a process of cultural and/or linguistic change in which something non-English becomes English. It can also refer to the influe ...

of the Latin . Scholars generally agree that Columbus was born in the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, RepÚbrica de ZÊna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

and spoke a dialect of Ligurian as his first language. He went to sea at a young age and travelled widely, as far north as the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isl ...

and as far south as what is now Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

. He married Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo, who bore his son Diego, and was based in Lisbon for several years. He later took a Castilian mistress, Beatriz EnrÃquez de Arana, who bore his son, Fernando (also given as Hernando).

Largely self-educated, Columbus was knowledgeable in geography, astronomy, and history. He developed a plan to seek a western sea passage to the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

, hoping to profit from the lucrative spice trade. After the Granada War

The Granada War ( es, Guerra de Granada) was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1491 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It e ...

, and following Columbus's persistent lobbying in multiple kingdoms, the Catholic Monarchs Queen Isabella I

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 â 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la CatÃģlica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 by ...

and King Ferdinand II

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 â 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el CatÃģlico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia from ...

agreed to sponsor a journey west. Columbus left Castile in August 1492 with three ships and made landfall in the Americas on 12 October, ending the period of human habitation in the Americas now referred to as the pre-Columbian era

In the history of the Americas, the pre-Columbian era spans from the original settlement of North and South America in the Upper Paleolithic period through European colonization, which began with Christopher Columbus's voyage of 1492. Usually, ...

. His landing place was an island in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the a ...

, known by its native inhabitants as Guanahani

Guanahanà is an island in the Bahamas that was the first land in the New World sighted and visited by Christopher Columbus' first voyage, on 12 October 1492. It is a bean-shaped island that Columbus changed from its native TaÃno name to San ...

. He subsequently visited the islands now known as Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, RepÚblica de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La EspaÃąola; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, establishing a colony in what is now Haiti. Columbus returned to Castile in early 1493, bringing a number of captured natives with him. Word of his voyage soon spread throughout Europe.

Columbus made three further voyages to the Americas, exploring the Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

in 1493, Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and the northern coast of South America in 1498, and the eastern coast of Central America in 1502. Many of the names he gave to geographical features, particularly islands, are still in use. He also gave the name ''indios'' ("Indians") to the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

he encountered. The extent to which he was aware that the Americas were a wholly separate landmass is uncertain; he never clearly renounced his belief that he had reached the Far East. As a colonial governor, Columbus was accused by his contemporaries of significant brutality and was soon removed from the post. Columbus's strained relationship with the Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and LeÃģn upon the accessi ...

and its appointed colonial administrators in America led to his arrest and removal from Hispaniola in 1500, and later to protracted litigation over the perquisites that he and his heirs claimed were owed to them by the crown.

Columbus's expeditions inaugurated a period of exploration, conquest, and colonization that lasted for centuries, thus bringing the Americas into the European sphere of influence. The transfer of commodities, ideas, and people between the Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by thei ...

and New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

that followed his first voyage are known as the Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

. Columbus was widely celebrated in the centuries after his death, but public perception has fractured in the 21st century as scholars have given greater attention to the harms committed under his governance, particularly the beginning of the depopulation of Hispaniola's indigenous TaÃno

The TaÃno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by TaÃno descendant communities and TaÃno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

s caused by mistreatment and Old World diseases, as well as by that people's enslavement. Many places

Place may refer to:

Geography

* Place (United States Census Bureau), defined as any concentration of population

** Census-designated place, a populated area lacking its own municipal government

* "Place", a type of street or road name

** Ofte ...

in the Western Hemisphere bear his name, including the country of Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North Americaânear Nicaragua's Caribbean coastâas well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the ...

, the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.), Logan Circle, Jefferson Memoria ...

, and British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, for ...

.

Early life

Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the

Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, RepÚbrica de ZÊna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

between 25 August and 31 October 1451. His father was Domenico Colombo

Domenico Colombo ( en, Dominic Columbus; lij, label= Genoese, Domenego Corombo; 1 March 14181496) was a weaver, the father of Italian explorer and navigator Christopher Columbus and Bartholomew Columbus.

Biography

Domenico was born in 1418. H ...

, a wool weaver who worked in Genoa and Savona

Savona (; lij, Sann-a ) is a seaport and ''comune'' in the west part of the northern Italy, Italian region of Liguria, capital of the Province of Savona, in the Riviera di Ponente on the Mediterranean Sea.

Savona used to be one of the chie ...

and who also owned a cheese stand at which young Christopher worked as a helper. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa

Susanna of Fontanarossa (1435â1489) was the mother of navigator and explorer Christopher Columbus.

Biography

Susanna was born in the hillside village of Monticellu, on the then Genoese island of Corsica, to a wealthy Catholic family. Her ...

. He had three brothersâBartolomeo Bartolomeo or Bartolommeo is a masculine Italian given name, the Italian equivalent of Bartholomew. Its diminutive form is Baccio. Notable people with the name include:

* Abramo Bartolommeo Massalongo (1824â1860), Italian paleobotanist and lich ...

, Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo (also called Diego)âas well as a sister named Bianchinetta. His brother Bartolomeo ran a cartography

Cartography (; from grc, ÏÎŽÏÏÎ·Ï , "papyrus, sheet of paper, map"; and , "write") is the study and practice of making and using maps. Combining science, aesthetics and technique, cartography builds on the premise that reality (or an i ...

workshop in Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

for at least part of his adulthood.

His native language is presumed to have been a Genoese dialect

Genoese, locally called or , is the main Ligurian dialect, spoken in and around the Italian city of Genoa, the capital of Liguria, in Northern Italy.

A majority of remaining speakers of Genoese are elderly. Several associations are dedicated ...

although Columbus probably never wrote in that language. His name in the 16th-century Genoese language was ''Cristoffa Corombo'' (). His name in Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

is ''Cristoforo Colombo'', and in Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

''CristÃģbal ColÃģn''.

In one of his writings, he says he went to sea at the age of fourteen. In 1470, the Colombo family moved to Savona

Savona (; lij, Sann-a ) is a seaport and ''comune'' in the west part of the northern Italy, Italian region of Liguria, capital of the Province of Savona, in the Riviera di Ponente on the Mediterranean Sea.

Savona used to be one of the chie ...

, where Domenico took over a tavern. Some modern authors have argued that he was not from Genoa but, instead, from the Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, AragÃģn ; ca, AragÃģ ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to s ...

region of Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de EspaÃąa.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de EspaÃąa (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

or from Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, RepÚblica Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

. These competing hypotheses generally have been discounted by mainstream scholars.

In 1473, Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the wealthy Spinola, Centurione, and Di Negro families of Genoa. Later, he made a trip to Chios

Chios (; el, ΧÎŊÎŋÏ, ChÃos , traditionally known as Scio in English) is the fifth largest Greek island, situated in the northern Aegean Sea. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. Chios is notable for its exports of mast ...

, an Aegean island then ruled by Genoa. In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably visited Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, city, Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Glouces ...

, England, and Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a City status in Ireland, city in the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lo ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Ãire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

, where he may have visited St. Nicholas Collegiate Church. It has been speculated that he had also gone to Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ãsland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is ReykjavÃk, which (along with its ...

in 1477, although many scholars doubt it. It is known that in the autumn of 1477, he sailed on a Portuguese ship from Galway to Lisbon, where he found his brother Bartolomeo, and they continued trading for the Centurione family. Columbus based himself in Lisbon from 1477 to 1485. In 1478, the Centuriones sent Columbus on a sugar-buying trip to Madeira. He married Felipa Perestrello e Moniz, daughter of Bartolomeu Perestrello

Bartolomeu Perestrello (, in Italian ''Bartolomeo Perestrello''), 1st CapitÃĢo DonatÃĄrio, Lord and Governor of the Island of Porto Santo ( 1395 â 1457) was a Portuguese navigator and explorer that is claimed to have discovered and populated ...

, a Portuguese nobleman of Lombard origin, who had been the donatary captain

A donatary captain was a Portuguese colonial official to whom the Crown granted jurisdiction, rights, and revenues over some colonial territory. The recipients of these grants were called (donataries), because they had been given the grant as a ( ...

of Porto Santo

Porto Santo Island () is a Portuguese island northeast of Madeira Island in the North Atlantic Ocean; it is the northernmost and easternmost island of the archipelago of Madeira, located in the Atlantic Ocean west of Europe and Africa.

The mun ...

.

In 1479 or 1480, Columbus's son Diego

Diego is a Spanish masculine given name. The Portuguese equivalent is Diogo. The name also has several patronymic derivations, listed below. The etymology of Diego is disputed, with two major origin hypotheses: ''Tiago'' and ''Didacus''.

...

was born. Between 1482 and 1485, Columbus traded along the coasts of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

, reaching the Portuguese trading post of Elmina

Elmina, also known as Edina by the local Fante, is a town and the capital of the Komenda/Edina/Eguafo/Abirem District on the south coast of Ghana in the Central Region, situated on a bay on the Atlantic Ocean, west of Cape Coast. Elmina wa ...

at the Guinea coast

Guinea is a traditional name for the region of the African coast of West Africa which lies along the Gulf of Guinea. It is a naturally moist tropical forest or savanna that stretches along the coast and borders the Sahel belt in the north.

Et ...

(in present-day Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

). Before 1484, Columbus returned to Porto Santo to find that his wife had died. He returned to Portugal to settle her estate and take his son Diego with him. He left Portugal for Castile in 1485, where he found a mistress in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named Beatriz EnrÃquez de Arana.

It is likely that Beatriz met Columbus when he was in CÃģrdoba, a gathering site of many Genoese merchants and where the court of the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of TrastÃĄmara and were second cousins, being bot ...

was located at intervals. Beatriz, unmarried at the time, gave birth to Columbus's second son, Fernando Columbus

Ferdinand Columbus (Spanish: ''Fernando ColÃģn'' also ''Hernando'', Portuguese: ''Fernando Colombo'', Italian: ''Fernando Colombo''; c. 24 August 1488 â 12 July 1539) was a Spanish bibliographer and cosmographer, the second son of Christopher ...

, in July 1488, named for the monarch of Aragon. Columbus recognized the boy as his offspring. Columbus entrusted his older, legitimate son Diego to take care of Beatriz and pay the pension set aside for her following his death, but Diego was negligent in his duties.

Being ambitious, Columbus eventually learned

Being ambitious, Columbus eventually learned Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

, Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

, and Castilian. He read widely about astronomy, geography, and history, including the works of Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Î ÏÎŋÎŧÎĩΞιáŋÎŋÏ, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importa ...

, Pierre Cardinal d'Ailly's ''Imago Mundi'', the travels of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

and Sir John Mandeville

Sir John Mandeville is the supposed author of ''The Travels of Sir John Mandeville'', a travel memoir which first circulated between 1357 and 1371. The earliest-surviving text is in French.

By aid of translations into many other languages, the ...

, Pliny's '' Natural History'', and Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 â 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 Augu ...

's '' Historia Rerum Ubique Gestarum''. According to historian Edmund Morgan,

Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong ...

Quest for Asia

Background

Under the

Under the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire of the 13th and 14th centuries was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Europe, ...

's hegemony over Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

and the ''Pax Mongolica

The ''Pax Mongolica'' (Latin for "Mongol Peace"), less often known as ''Pax Tatarica'' ("Tatar Peace"), is a historiographical term modelled after the original phrase ''Pax Romana'' which describes the stabilizing effects of the conquests of the ...

'', Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage on the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

to parts of East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea ...

(including China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

) and Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor. Maritime Southeast Asia is sometimes also referred to as Island Southeast Asia, Insular Southeast Asia or Oceanic Sout ...

, which were sources of valuable goods. With the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, ÐÎļÏÎžÎąÎ―ÎđΚÎŪ ÎÏ

ÏÎŋΚÏÎąÏÎŋÏÎŊÎą, OthÅmanikÄ Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

in 1453, the Silk Road was closed to Christian traders.

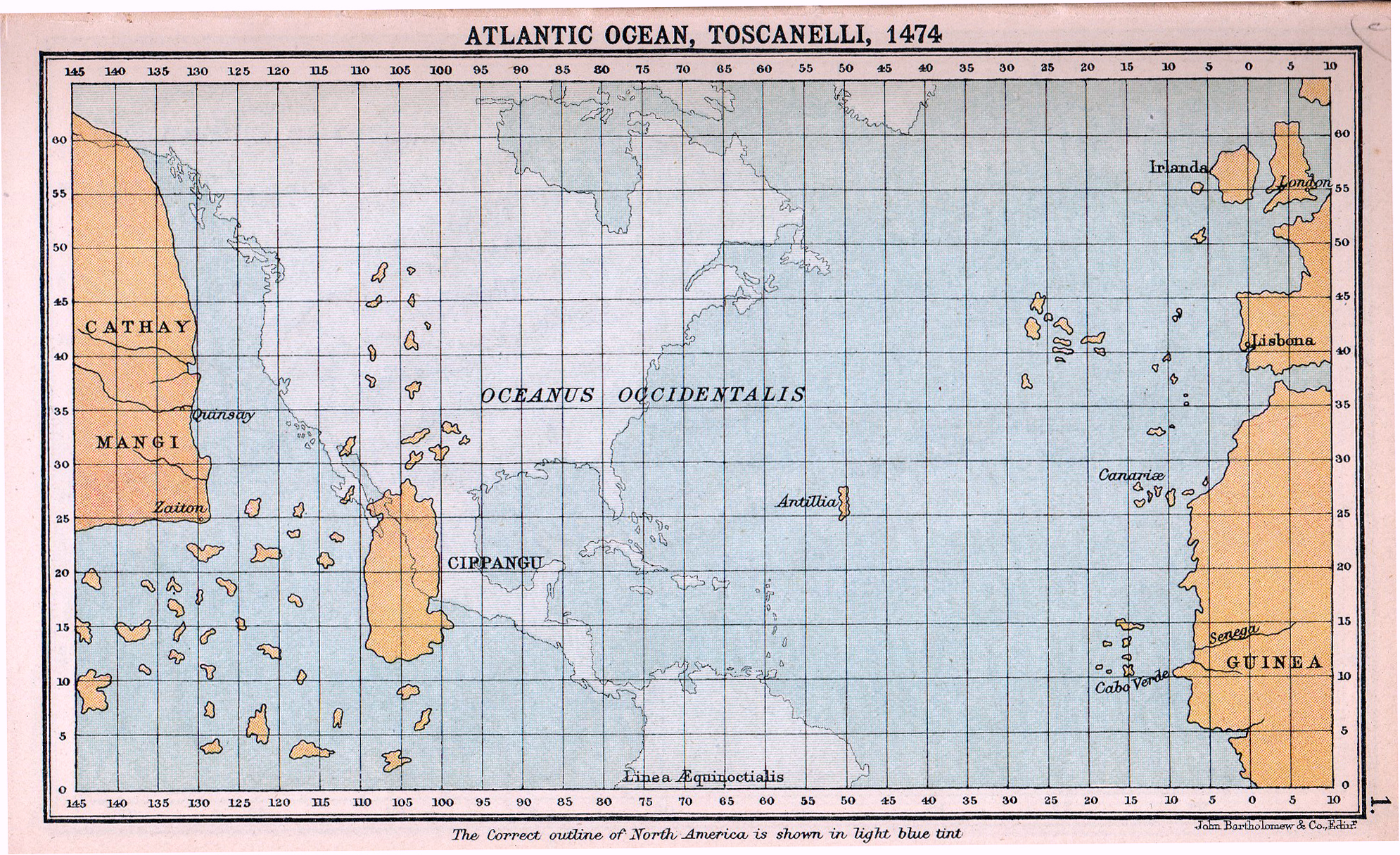

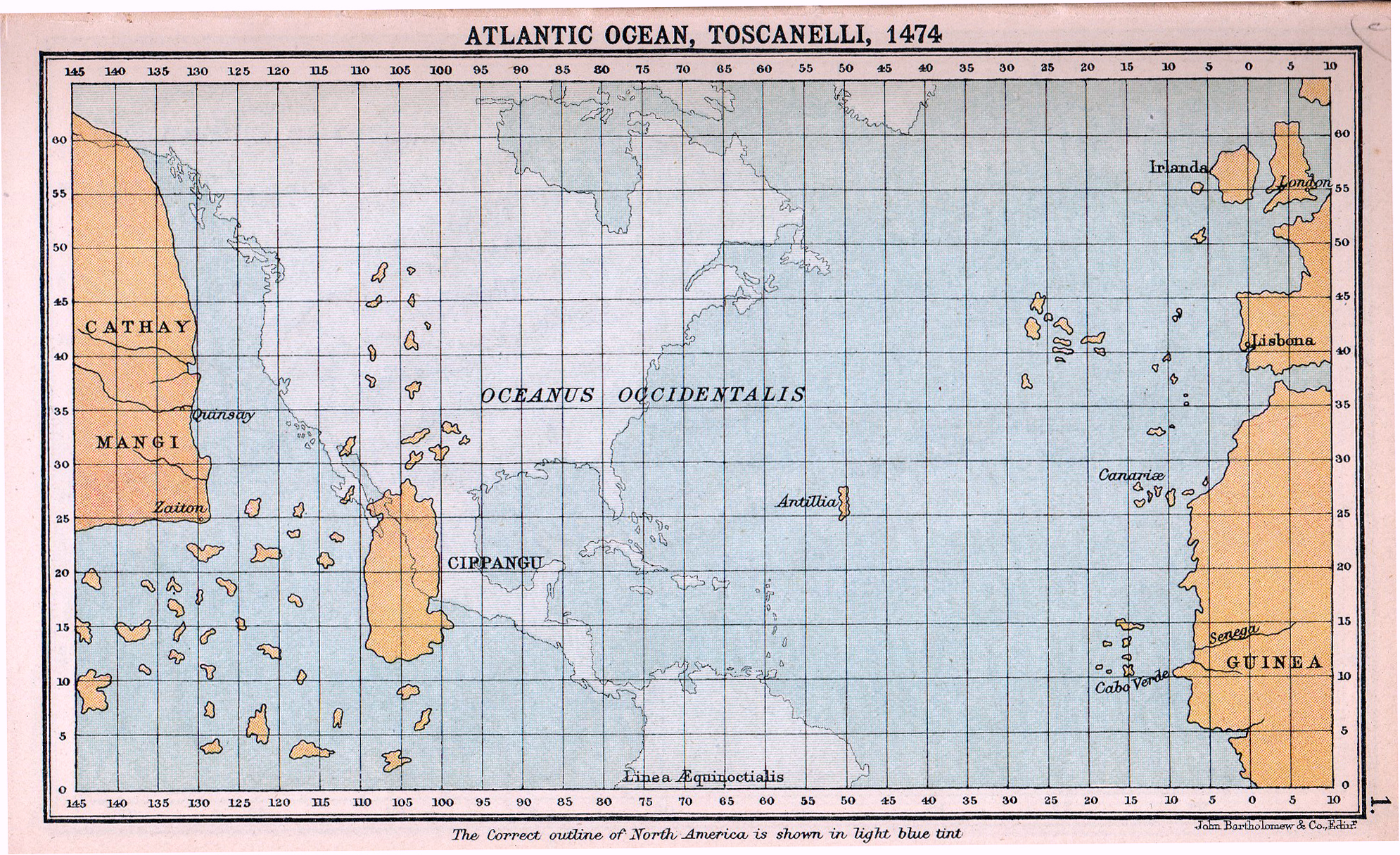

In 1474, the Florentine astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli

Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1397 â 10 May 1482) was an Italian mathematician, astronomer,, pp. 333â335 and cosmographer.

Life

Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli was born in Florence, the son of the physician Domenico Toscanelli. There is no ...

suggested to King Afonso V of Portugal

Afonso V () (15 January 1432 â 28 August 1481), known by the sobriquet the African (), was King of Portugal from 1438 until his death in 1481, with a brief interruption in 1477. His sobriquet refers to his military conquests in Northern Afri ...

that sailing west across the Atlantic would be a quicker way to reach the Maluku (Spice) Islands, China, and Japan than the route around Africa, but Afonso rejected his proposal. In the 1480s, Columbus and his brother proposed a plan to reach the East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around ...

by sailing west. Columbus supposedly wrote Toscanelli in 1481 and received encouragement, along with a copy of a map the astronomer had sent Afonso implying that a westward route to Asia was possible. Columbus's plans were complicated by the opening of the Cape Route

The European-Asian sea route, commonly known as the sea route to India or the Cape Route, is a shipping route from the European coast of the Atlantic Ocean to Asia's coast of the Indian Ocean passing by the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas ...

to Asia around Africa in 1488.

Carol Delaney and other commentators have argued that Columbus was a Christian millennialist and apocalypticist and that these beliefs motivated his quest for Asia in a variety of ways. Columbus often wrote about seeking gold in the log books of his voyages and writes about acquiring the precious metal "in such quantity that the sovereigns... will undertake and prepare to go conquer the Holy Sepulcher" in a fulfillment of Biblical prophecy

Bible prophecy or biblical prophecy comprises the passages of the Bible that are claimed to reflect communications from God to humans through prophets. Jews and Christians usually consider the biblical prophets to have received revelations from G ...

. Columbus also often wrote about converting all races to Christianity. Abbas Hamandi argues that Columbus was motivated by the hope of " eliveringJerusalem from Muslim hands" by "using the resources of newly discovered lands".

Geographical considerations

Despite a popular misconception to the contrary, nearly all educated Westerners of Columbus's time knew that the Earth is spherical, a concept that had been understood sinceantiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

. The techniques of celestial navigation

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space (or on the surface o ...

, which uses the position of the Sun and the stars in the sky, had long been in use by astronomers and were beginning to be implemented by mariners.

As far back as the 3rd century BC, Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, ážÏÎąÏÎŋÏÎļÎÎ―Î·Ï ; â ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandr ...

had correctly computed the circumference of the Earth by using simple geometry and studying the shadows cast by objects at two remote locations. In the 1st century BC, Posidonius

Posidonius (; grc-gre, Î ÎŋÏÎĩÎđÎīÏÎ―ÎđÎŋÏ , "of Poseidon") "of Apameia" (á― ážÏιΞÎĩÏÏ) or "of Rhodes" (á― áŋŽÏÎīÎđÎŋÏ) (), was a Greek politician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, historian, mathematician, and teacher nativ ...

confirmed Eratosthenes's results by comparing stellar observations at two separate locations. These measurements were widely known among scholars, but Ptolemy's use of the smaller, old-fashioned units of distance led Columbus to underestimate the size of the Earth by about a third.

Three

Three cosmographical

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-sca ...

parameters determined the bounds of Columbus's enterprise: the distance across the ocean between Europe and Asia, which depended on the extent of the oikumene

The ecumene ( US spelling) or oecumene ( UK spelling; grc-gre, ÎŋឰΚÎŋÏ

ΞÎÎ―Î·, oikoumÃĐnÄ, inhabited) is an ancient Greek term for the known, the inhabited, or the habitable world. In Greek antiquity, it referred to the portions of the worl ...

, i.e., the Eurasian land-mass stretching east-west between Spain and China; the circumference of the Earth; and the number of miles or leagues in a degree of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the eastâ west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

, which was possible to deduce from the theory of the relationship between the size of the surfaces of water and the land as held by the followers of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, ážÏÎđÏÏÎŋÏÎÎŧÎ·Ï ''AristotÃĐlÄs'', ; 384â322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

in medieval times.

From Pierre d'Ailly

Pierre d'Ailly (; Latin ''Petrus Aliacensis'', ''Petrus de Alliaco''; 13519 August 1420) was a French theologian, astrologer and cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.

Academic career

D'Ailly was born in CompiÃĻgne in 1350 or 1351 of a prospero ...

's ''Imago Mundi

''Imago Mundi'', or in full ''Imago Mundi: International Journal for the History of Cartography'', is a semiannual peer-reviewed academic journal about mapping, established in 1935 by Leo Bagrow. It covers the history of early maps, cartography ...

'' (1410), Columbus learned of Alfraganus

AbÅŦ al-ĘŋAbbÄs AáļĨmad ibn MuáļĨammad ibn KathÄŦr al-FarghÄnÄŦ ( ar, ØĢØĻŲ اŲØđØĻŲاØģ ØĢØŲ

ØŊ ØĻŲ Ų

ØŲ

ØŊ ØĻŲ ŲØŦŲØą اŲŲØąØšØ§ŲŲ 798/800/805â870), also known as Alfraganus in the West, was an astronomer in the Abbasid court ...

's estimate that a degree of latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the northâ south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from â90° at the south pole to 90° at the north ...

(equal to approximately a degree of longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the eastâ west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek let ...

along the equator) spanned 56.67 Arabic mile

The Arab, Arabic, or Arabian mile ( ar, اŲŲ

ŲŲ, ''al-mÄŦl'') was a historical Arabic unit of length. Its precise length is disputed, lying between 1.8 and 2.0 km. It was used by medieval Arab geographers and astronomers. The predecessor o ...

s (equivalent to or 76.2 mi), but he did not realize that this was expressed in the Arabic mile (about ) rather than the shorter Roman mile

The mile, sometimes the international mile or statute mile to distinguish it from other miles, is a British imperial unit and United States customary unit of distance; both are based on the older English unit of length equal to 5,280 Engli ...

(about 1,480 m) with which he was familiar. Columbus therefore estimated the size of the Earth to be about 75% of Eratosthenes's calculation, and the distance westward from the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; es, :es:Canarias, Canarias, ), also known informally as the Canaries, are a Spanish Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community and archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, in Macaronesia. At their closest point to ...

to the Indies as only 68 degrees, equivalent to (a 58% margin of error).

Most scholars of the time accepted Ptolemy's estimate that Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

spanned 180° longitude, rather than the actual 130° (to the Chinese mainland) or 150° (to Japan at the latitude of Spain). Columbus believed an even higher estimate, leaving a smaller percentage for water. In d'Ailly's ''Imago Mundi'', Columbus read Marinus of Tyre

Marinus of Tyre ( grc-gre, ÎÎąÏáŋÎ―ÎŋÏ á― ÎĪÏÏÎđÎŋÏ, ''MarÃŪnos ho TÃ―rios''; 70â130) was a Greek geographer, cartographer and mathematician, who founded mathematical geography and provided the underpinnings of Claudius Ptolemy' ...

's estimate that the longitudinal span of Eurasia was 225° at the latitude of Rhodes

Rhodes (; el, ÎĄÏÎīÎŋÏ , translit=RÃģdos ) is the largest and the historical capital of the Dodecanese islands of Greece. Administratively, the island forms a separate municipality within the Rhodes regional unit, which is part of the S ...

. Some historians, such as Samuel Morison, have suggested that he followed the statement in the apocryphal

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ážÏÏΚÏÏ

ÏÎŋÏ) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

book 2 Esdras

2 Esdras (also called 4 Esdras, Latin Esdras, or Latin Ezra) is an apocalyptic book in some English versions of the Bible. Tradition ascribes it to Ezra, a scribe and priest of the , but scholarship places its composition between 70 and .

It ...

( 6:42) that "six parts f the globeare habitable and the seventh is covered with water." He was also aware of Marco Polo's claim that Japan (which he called "Cipangu") was some to the east of China ("Cathay"), and closer to the equator than it is. He was influenced by Toscanelli's idea that there were inhabited islands even farther to the east than Japan, including the mythical Antillia, which he thought might lie not much farther to the west than the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

.

Based on his sources, Columbus estimated a distance of from the Canary Islands west to Japan; the actual distance is . No ship in the 15th century could have carried enough food and fresh water for such a long voyage, and the dangers involved in navigating through the uncharted ocean would have been formidable. Most European navigators reasonably concluded that a westward voyage from Europe to Asia was unfeasible. The Catholic Monarchs, however, having completed the ''Reconquista

The ' ( Spanish, Portuguese and Galician for "reconquest") is a historiographical construction describing the 781-year period in the history of the Iberian Peninsula between the Umayyad conquest of Hispania in 711 and the fall of the N ...

'', an expensive war against the Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinc ...

in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: PÃĐninsule IbÃĐrique

* mwl, PenÃnsula EibÃĐrica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, def ...

, were eager to obtain a competitive edge over other European countries in the quest for trade with the Indies. Columbus's project, though far-fetched, held the promise of such an advantage.

Nautical considerations

Though Columbus was wrong about the number of degrees of longitude that separated Europe from the Far East and about the distance that each degree represented, he did take advantage of thetrade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisp ...

, which would prove to be the key to his successful navigation of the Atlantic Ocean. He planned to first sail to the Canary Islands before continuing west with the northeast trade wind. Part of the return to Spain would require traveling against the wind using an arduous sailing technique called beating, during which progress is made very slowly. To effectively make the return voyage, Columbus would need to follow the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he would be able to catch the "westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes and tren ...

" that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe.

The navigational technique for travel in the Atlantic appears to have been exploited first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the ''volta do mar

, , or (the phrase in Portuguese means literally 'turn of the sea' but also 'return from the sea') is a navigational technique perfected by Portuguese navigators during the Age of Discovery in the late fifteenth century, using the dependable ...

'' ('turn of the sea'). Through his marriage to his first wife, Felipa Perestrello, Columbus had access to the nautical charts and logs that had belonged to her deceased father, Bartolomeu Perestrello, who had served as a captain in the Portuguese navy under Prince Henry the Navigator

''Dom'' Henrique of Portugal, Duke of Viseu (4 March 1394 â 13 November 1460), better known as Prince Henry the Navigator ( pt, Infante Dom Henrique, o Navegador), was a central figure in the early days of the Portuguese Empire and in the 15t ...

. In the mapmaking shop where he worked with his brother Bartolomeo, Columbus also had ample opportunity to hear the stories of old seamen about their voyages to the western seas, but his knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was still imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing due west from the Canary Islands during hurricane season, skirting the so-called horse latitudes of the mid-Atlantic, he risked being becalmed and running into a tropical cyclone

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system characterized by a low-pressure center, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Dep ...

, both of which he avoided by chance.

Quest for financial support for a voyage

By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King

By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King John II of Portugal

John II ( pt, JoÃĢo II; ; 3 March 1455 â 25 October 1495), called the Perfect Prince ( pt, o PrÃncipe Perfeito, link=no), was King of Portugal from 1481 until his death in 1495, and also for a brief time in 1477. He is known for re-establishi ...

. The king submitted Columbus's proposal to his advisors, who rejected it, correctly, on the grounds that Columbus's estimate for a voyage of 2,400 nmi was only a quarter of what it should have been. In 1488, Columbus again appealed to the court of Portugal, and John II again granted him an audience. That meeting also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards Bartolomeu Dias

Bartolomeu Dias ( 1450 â 29 May 1500) was a Portuguese mariner and explorer. In 1488, he became the first European navigator to round the southern tip of Africa and to demonstrate that the most effective southward route for ships lay in the o ...

returned to Portugal with news of his successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa (near the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

).

Columbus sought an audience with the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II ( an, Ferrando; ca, Ferran; eu, Errando; it, Ferdinando; la, Ferdinandus; es, Fernando; 10 March 1452 â 23 January 1516), also called Ferdinand the Catholic (Spanish: ''el CatÃģlico''), was King of Aragon and Sardinia fro ...

and Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I ( es, Isabel I; 22 April 1451 â 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''la CatÃģlica''), was Queen of Castile from 1474 until her death in 1504, as well as Queen consort of Aragon from 1479 until 1504 b ...

, who had united several kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula by marrying and were now ruling together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. The learned men of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, replied that Columbus had grossly underestimated the distance to Asia. They pronounced the idea impractical and advised the Catholic Monarchs to pass on the proposed venture. To keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the sovereigns gave him an allowance, totaling about 14,000 '' maravedis'' for the year, or about the annual salary of a sailor. In May 1489, the queen sent him another 10,000 ''maravedis'', and the same year the monarchs furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their dominion to provide him food and lodging at no cost.

Columbus also dispatched his brother Bartolomeo Bartolomeo or Bartolommeo is a masculine Italian given name, the Italian equivalent of Bartholomew. Its diminutive form is Baccio. Notable people with the name include:

* Abramo Bartolommeo Massalongo (1824â1860), Italian paleobotanist and lich ...

to the court of Henry VII of England

Henry VII (28 January 1457 â 21 April 1509) was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizure of the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death in 1509. He was the first monarch of the House of Tudor.

Henry's mother, Margaret Beauf ...

to inquire whether the English crown might sponsor his expedition, but he was captured by pirates en route, and only arrived in early 1491. By that time, Columbus had retreated to La RÃĄbida Friary, where the Spanish crown sent him 20,000 ''maravedis'' to buy new clothes and instructions to return to the Spanish court for renewed discussions.

Agreement with the Spanish crown

Columbus waited at King Ferdinand's camp until Ferdinand and Isabella conqueredGranada

Granada (,, DIN: ; grc, ážÎŧÎđÎēÏÏÎģη, ElibÃ―rgÄ; la, Illiberis or . ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains, at the c ...

, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, in January 1492. A council led by Isabella's confessor, Hernando de Talavera

Hernando de Talavera, O.S.H. (c. 1430 – 14 May 1507) was a Spanish clergyman and councilor to Queen Isabel of Castile. He began his career as a monk of the Order of Saint Jerome, was appointed the queen's confessor and with her support and ...

, found Columbus's proposal to reach the Indies implausible. Columbus had left for France when Ferdinand intervened, first sending Talavera and Bishop Diego Deza

Diego de Deza y Tavera (1444 â 9 June 1523) was a theologian and inquisitor of Spain. He was one of the more notable figures in the Spanish Inquisition, and succeeded TomÃĄs de Torquemada to the post of Grand Inquisitor.

Early life

Deza was ...

to appeal to the queen. Isabella was finally convinced by the king's clerk Luis de SantÃĄngel

Luis de SantÃĄngel (died 1498) was a third generation ''converso'' in Spain during the late fifteenth century. SantÃĄngel worked as ''escribano de raciÃģn'' to King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella I of Spain which left him in charge of the Royal ...

, who argued that Columbus would take his ideas elsewhere, and offered to help arrange the funding. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch Columbus, who had traveled 2 leagues (over 10 km) toward CÃģrdoba.

In the April 1492 "Capitulations of Santa Fe

The Capitulations of Santa Fe between Christopher Columbus and the Catholic Monarchs, Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, were signed in Santa Fe, Granada on April 17, 1492. They granted Columbus the titles of admiral of ...

", King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella promised Columbus that if he succeeded he would be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and appointed Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning " ...

and Governor of all the new lands he might claim for Spain. He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10% (''diezmo

The ''diezmo'' was a compulsory ecclesiastical tithe collected in Spain and its empire from the Middle Ages until the reign of Isabel II in the mid-19th century.

History

The obligatory tithe was introduced to the Iberian peninsula in AragÃģn and ...

'') of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity. He also would have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture in the new lands, and receive one-eighth (''ochavo'') of the profits.

In 1500, during his third voyage to the Americas, Columbus was arrested and dismissed from his posts. He and his sons, Diego and Fernando, then conducted a lengthy series of court cases against the Castilian crown, known as the ''pleitos colombinos

The ''Pleitos colombinos'' ("Colombian lawsuits") were a long series of lawsuits that the heirs of Christopher Columbus brought against the Crown of Castile and LeÃģn in defense of the privileges obtained by Columbus for his discoveries in the N ...

'', alleging that the Crown had illegally reneged on its contractual obligations to Columbus and his heirs. The Columbus family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as viceroy but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes initiated by heirs continued until 1790.

Voyages

Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

, each voyage being sponsored by the Crown of Castile

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and LeÃģn upon the accessi ...

. On his first voyage he reached the Americas, initiating the European exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

and colonization of the continent, as well as the Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

. His role in history is thus important to the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafa ...

, Western history, and human history

Human history, also called world history, is the narrative of humanity's past. It is understood and studied through anthropology, archaeology, genetics, and linguistics. Since the invention of writing, human history has been studied thro ...

writ large.

In Columbus's letter on the first voyage

A letter written by Christopher Columbus on February 15, 1493 is the first known document announcing the results of his first voyage that set out in 1492 and reached the Americas. The letter was ostensibly written by Columbus himself, aboard the ...

, published following his first return to Spain, he claimed that he had reached Asia, as previously described by Marco Polo and other Europeans. Over his subsequent voyages, Columbus refused to acknowledge that the lands he visited and claimed for Spain were not part of Asia, in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary. This might explain, in part, why the American continent was named after the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucciâwho received credit for recognizing it as a "New World

The term ''New World'' is often used to mean the majority of Earth's Western Hemisphere, specifically the Americas."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: Oxford University Press, p. ...

"âand not after Columbus.

First voyage (1492â1493)

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from

On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from Palos de la Frontera

Palos de la Frontera () is a town and municipality located in the southwestern Spanish province of Huelva, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is situated some from the provincial capital, Huelva. According to the 2015 census, the cit ...

with three ships. The largest was a carrack

A carrack (; ; ; ) is a three- or four- masted ocean-going sailing ship that was developed in the 14th to 15th centuries in Europe, most notably in Portugal. Evolved from the single-masted cog, the carrack was first used for European trade ...

, the '' Santa MarÃa'', owned and captained by Juan de la Cosa

Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450 â 28 February 1510) was a Castilian navigator and cartographer, known for designing the earliest European world map which incorporated the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century.

De la Cosa was th ...

, and under Columbus's direct command. The other two were smaller caravel

The caravel (Portuguese: , ) is a small maneuverable sailing ship used in the 15th century by the Portuguese to explore along the West African coast and into the Atlantic Ocean. The lateen sails gave it speed and the capacity for sailing w ...

s, the '' Pinta'' and the ''NiÃąa

''La NiÃąa'' ( Spanish for ''The Girl'') was one of the three Spanish ships used by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus in his first voyage to the West Indies in 1492. As was tradition for Spanish ships of the day, she bore a female saint's n ...

'', piloted by the PinzÃģn brothers. Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands. There he restocked provisions and made repairs then departed from San SebastiÃĄn de La Gomera

San SebastiÃĄn de La Gomera is the capital and a municipality of La Gomera in the Canary Islands, Spain. It also hosts the main harbour. The population was 8,699 in 2013,mense flocks of birds". On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet's course to due west, and sailed through the night, believing land was soon to be found. At around 02:00 the following morning, a lookout on the ''Pinta'',

On 24 September 1493, Columbus sailed from

On 24 September 1493, Columbus sailed from

On 30 May 1498, Columbus left with six ships from SanlÚcar, Spain. The fleet called at Madeira and the Canary Islands, where it divided in two, with three ships heading for Hispaniola and the other three vessels, commanded by Columbus, sailing south to the Cape Verde Islands and then westward across the Atlantic. It is probable that this expedition was intended at least partly to confirm rumors of a large continent south of the Caribbean Sea, that is, South America.

On 31 July they sighted

On 30 May 1498, Columbus left with six ships from SanlÚcar, Spain. The fleet called at Madeira and the Canary Islands, where it divided in two, with three ships heading for Hispaniola and the other three vessels, commanded by Columbus, sailing south to the Cape Verde Islands and then westward across the Atlantic. It is probable that this expedition was intended at least partly to confirm rumors of a large continent south of the Caribbean Sea, that is, South America.

On 31 July they sighted

On 9 May 1502, Columbus left CÃĄdiz with his flagship ''Santa MarÃa'' and three other vessels. The ships were crewed by 140 men, including his brother Bartolomeo as second in command and his son Fernando. He sailed to

On 9 May 1502, Columbus left CÃĄdiz with his flagship ''Santa MarÃa'' and three other vessels. The ships were crewed by 140 men, including his brother Bartolomeo as second in command and his son Fernando. He sailed to

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the landing of Columbus, the 1893

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of the landing of Columbus, the 1893

His explorations resulted in permanent contact between the two hemispheres, and the term "

His explorations resulted in permanent contact between the two hemispheres, and the term " The Americanization of the figure of Columbus began in the latter decades of the 18th century, after the revolutionary period of the United States, elevating the status of his reputation to a national myth, ''homo americanus''. His landing became a powerful icon as an "image of American genesis". ''

The Americanization of the figure of Columbus began in the latter decades of the 18th century, after the revolutionary period of the United States, elevating the status of his reputation to a national myth, ''homo americanus''. His landing became a powerful icon as an "image of American genesis". ''

Though Christopher Columbus came to be considered the European discoverer of America in Western popular culture, his historical legacy is more nuanced. After settling Iceland, the Norse settled the uninhabited southern part of

Though Christopher Columbus came to be considered the European discoverer of America in Western popular culture, his historical legacy is more nuanced. After settling Iceland, the Norse settled the uninhabited southern part of

Historians have traditionally argued that Columbus remained convinced until his death that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia as he originally intended (excluding arguments such as Anderson's). On his third voyage he briefly referred to South America as a "hitherto unknown" continent, while also rationalizing that it was the "Earthly Paradise" located "at the end of the Orient". Columbus continued to claim in his later writings that he had reached Asia; in a 1502 letter to

Historians have traditionally argued that Columbus remained convinced until his death that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia as he originally intended (excluding arguments such as Anderson's). On his third voyage he briefly referred to South America as a "hitherto unknown" continent, while also rationalizing that it was the "Earthly Paradise" located "at the end of the Orient". Columbus continued to claim in his later writings that he had reached Asia; in a 1502 letter to

Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because many Catholic theologians insisted that the Earth was flat, but this is a popular misconception which can be traced back to 17th-century Protestants campaigning against Catholicism. In fact, the spherical shape of the Earth had been known to scholars since antiquity, and was common knowledge among sailors, including Columbus. Coincidentally, the oldest surviving globe of the Earth, the

Washington Irving's 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because many Catholic theologians insisted that the Earth was flat, but this is a popular misconception which can be traced back to 17th-century Protestants campaigning against Catholicism. In fact, the spherical shape of the Earth had been known to scholars since antiquity, and was common knowledge among sailors, including Columbus. Coincidentally, the oldest surviving globe of the Earth, the

Some historians have criticized Columbus for initiating the widespread colonization of the Americas and for abusing its native population. On St. Croix, Columbus's friend Michele da Cuneoâaccording to his own accountâkept an indigenous woman he captured, whom Columbus "gave to im, then brutally raped her. The punishment for an indigenous person, aged 14 and older, failing to pay a hawk's bell, or ''cascabela'', worth of gold dust every six months (based on

Some historians have criticized Columbus for initiating the widespread colonization of the Americas and for abusing its native population. On St. Croix, Columbus's friend Michele da Cuneoâaccording to his own accountâkept an indigenous woman he captured, whom Columbus "gave to im, then brutally raped her. The punishment for an indigenous person, aged 14 and older, failing to pay a hawk's bell, or ''cascabela'', worth of gold dust every six months (based on

Metropolitan Museum of Art Sometime between 1531 and 1536,

The tropics of empire: Why Columbus sailed south to the Indies

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. * Wilford, John Noble (1991), ''The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, the Myth, the Legacy'', New York: Alfred A. Knopf. *

Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus

', translated and edited by

Excerpts from the log of Christopher Columbus's first voyage

* ttp://columbus.vanderkrogt.net/ Columbus Monuments Pages(overview of monuments for Columbus all over the world)

"But for Columbus There Would Be No America"

Tiziano Thomas Dossena, ''Bridgepugliausa.it'', 2012. {{DEFAULTSORT:Columbus, Christopher 1451 births 1506 deaths 1490s in Cuba 1490s in the Caribbean 1492 in North America 15th-century apocalypticists 15th-century explorers 15th-century Genoese people 16th-century Genoese people 15th-century Roman Catholics Spanish exploration in the Age of Discovery Burials at Seville Cathedral Colonial governors of Santo Domingo

Rodrigo de Triana

Rodrigo de Triana (born 1469 in Lepe, Huelva, Spain) was a Spanish sailor, believed to be the first European from the Age of Exploration to have seen the Americas. Born as Juan RodrÃguez Bermejo, Triana was the son of hidalgo and potter Vicen ...

, spotted land. The captain of the ''Pinta'', MartÃn Alonso PinzÃģn

MartÃn Alonso PinzÃģn, (; Palos de la Frontera, Huelva; c. 1441 â c. 1493) was a Spanish mariner, shipbuilder, navigator and exploration, explorer, oldest of the PinzÃģn brothers. He sailed with Christopher Columbus on his Voyages of Christoph ...

, verified the sight of land and alerted Columbus. Columbus later maintained that he had already seen a light on the land a few hours earlier, thereby claiming for himself the lifetime pension promised by Ferdinand and Isabella to the first person to sight land. Columbus called this island (in what is now the Bahamas) ''San Salvador'' (meaning "Holy Savior"); the natives called it Guanahani

Guanahanà is an island in the Bahamas that was the first land in the New World sighted and visited by Christopher Columbus' first voyage, on 12 October 1492. It is a bean-shaped island that Columbus changed from its native TaÃno name to San ...

. Christopher Columbus's journal entry of 12 October 1492 states:I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were; and they showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves; and I believed and believe that they come here from ''tierra firme'' to take them captive. They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion. Our Lord pleasing, at the time of my departure I will take six of them from here to Your Highnesses in order that they may learn to speak.Columbus called the inhabitants of the lands that he visited ''Los Indios'' (Spanish for "Indians"). He initially encountered the Lucayan,

TaÃno

The TaÃno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, indigenous people of the Caribbean whose culture has been continued today by TaÃno descendant communities and TaÃno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the ...

, and Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the TaÃno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

peoples. Noting their gold ear ornaments, Columbus took some of the Arawaks prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold. Columbus did not believe he needed to create a fortified outpost, writing, "the people here are simple in war-like matters ... I could conquer the whole of them with fifty men, and govern them as I pleased." The TaÃnos told Columbus that another indigenous tribe, Caribs, were fierce warriors and cannibals

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, bo ...

, who made frequent raids on the TaÃnos, often capturing their women.

Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, RepÚblica de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, where he landed on 28 October. On the night of 26 November, MartÃn Alonso PinzÃģn took the ''Pinta'' on an unauthorized expedition in search of an island called "Babeque" or "Baneque", which the natives had told him was rich in gold. Columbus, for his part, continued to the northern coast of Hispaniola

Hispaniola (, also ; es, La EspaÃąola; Latin and french: Hispaniola; ht, Ispayola; tnq, Ayiti or Quisqueya) is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and th ...

, where he landed on 6 December. There, the ''Santa MarÃa'' ran aground on 25 December 1492 and had to be abandoned. The wreck was used as a target for cannon fire to impress the native peoples. Columbus was received by the native ''cacique

A ''cacique'' (Latin American ; ; feminine form: ''cacica'') was a tribal chieftain of the TaÃno people, the indigenous inhabitants at European contact of the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The term is a S ...

'' Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men, including the interpreter Luis de Torres

Luis de Torres (died 1493) was Christopher Columbus's interpreter on his first voyage to America.

De Torres was a converso, apparently born Yosef ben HaLevi HaIvri chosen by Columbus for his knowledge of Hebrew, Chaldaic, and Arabic. After arrivi ...

, and founded the settlement of La Navidad

La Navidad ("The Nativity", i.e. Christmas) was a settlement that Christopher Columbus and his men established on the northeast coast of Haiti (near what is now Caracol, Nord-Est Department, Haiti) in 1492 from the remains of the Spanish ship th ...

, in present-day Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

. Columbus took more natives prisoner and continued his exploration. He kept sailing along the northern coast of Hispaniola with a single ship until he encountered PinzÃģn and the ''Pinta'' on 6 January.

On 13 January 1493, Columbus made his last stop of this voyage in the Americas, in the Bay of RincÃģn RincÃģn Bay is V-shape bayin the northeasternmost in the SamanÃĄ Peninsula in the Dominican Republic. The road to playa Rincon has been since paved all the way to the beach for easy access by car. The road right on the beach is a sand road to go up ...

in northeast Hispaniola. There he encountered the Ciguayos, the only natives who offered violent resistance during this voyage. The Ciguayos refused to trade the amount of bows and arrows that Columbus desired; in the ensuing clash one Ciguayo was stabbed in the buttocks and another wounded with an arrow in his chest. Because of these events, Columbus called the inlet the ''Golfo de Las Flechas'' ( Bay of Arrows).

Columbus headed for Spain on the ''NiÃąa'', but a storm separated him from the ''Pinta,'' and forced the ''NiÃąa'' to stop at the island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Half of his crew went ashore to say prayers of thanksgiving in a chapel for having survived the storm. But while praying, they were imprisoned by the governor of the island, ostensibly on suspicion of being pirates. After a two-day standoff, the prisoners were released, and Columbus again set sail for Spain.

Another storm forced Columbus into the port at Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administrative limits w ...

. From there he went to ''Vale do ParaÃso'' north of Lisbon to meet King John II of Portugal, who told Columbus that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of AlcÃĄÃ§ovas

The Treaty of AlcÃĄÃ§ovas (also known as Treaty or Peace of AlcÃĄÃ§ovas-Toledo) was signed on 4 September 1479 between the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon on one side and Afonso V and his son, Prince John of Portugal, on the other side ...

. After spending more than a week in Portugal, Columbus set sail for Spain. Returning to Palos on 15 March 1493, he was given a hero's welcome and soon afterward received by Isabella and Ferdinand in Barcelona.

Columbus's letter on the first voyage, dispatched to the Spanish court, was instrumental in spreading the news throughout Europe about his voyage. Almost immediately after his arrival in Spain, printed versions began to appear, and word of his voyage spread rapidly. Most people initially believed that he had reached Asia. The Bulls of Donation

The Bulls of Donation, also called the Alexandrine Bulls, and the Papal donations of 1493, are three papal bulls of Pope Alexander VI delivered in 1493 which granted overseas territories to Portugal and the Catholic Monarchs of Spain.

A fourth ...

, three papal bulls of Pope Alexander VI

Pope Alexander VI ( it, Alessandro VI, va, Alexandre VI, es, Alejandro VI; born Rodrigo de Borja; ca-valencia, Roderic Llançol i de Borja ; es, Rodrigo Lanzol y de Borja, lang ; 1431 â 18 August 1503) was head of the Catholic Churc ...

delivered in 1493, purported to grant overseas territories to Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, RepÚblica Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of th ...

and the Catholic Monarchs of Spain. They were replaced by the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in SetÚbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Em ...

of 1494.

The two earliest published copies of Columbus's letter on the first voyage aboard the NiÃąa

''La NiÃąa'' ( Spanish for ''The Girl'') was one of the three Spanish ships used by Italian explorer Christopher Columbus in his first voyage to the West Indies in 1492. As was tradition for Spanish ships of the day, she bore a female saint's n ...

were donated in 2017 by the Jay I. Kislak Foundation to the University of Miami

The University of Miami (UM, UMiami, Miami, U of M, and The U) is a private research university in Coral Gables, Florida. , the university enrolled 19,096 students in 12 colleges and schools across nearly 350 academic majors and programs, i ...

library in Coral Gables, Florida

Coral Gables, officially City of Coral Gables, is a city in Miami-Dade County, Florida. The city is located southwest of Downtown Miami. As of the 2020 U.S. census, it had a population of 49,248.

Coral Gables is known globally as home to the ...

, where they are housed.

Second voyage (1493â1496)

On 24 September 1493, Columbus sailed from

On 24 September 1493, Columbus sailed from CÃĄdiz

CÃĄdiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of CÃĄdiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

CÃĄdiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

with 17 ships, and supplies to establish permanent colonies in the Americas. He sailed with nearly 1,500 men, including sailors, soldiers, priests, carpenters, stonemasons, metalworkers, and farmers. Among the expedition members were Alvarez Chanca, a physician who wrote a detailed account of the second voyage; Juan Ponce de LeÃģn, the first governor of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and unincorporated ...

and Florida; the father of BartolomÃĐ de las Casas; Juan de la Cosa

Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450 â 28 February 1510) was a Castilian navigator and cartographer, known for designing the earliest European world map which incorporated the territories of the Americas discovered in the 15th century.

De la Cosa was th ...

, a cartographer who is credited with making the first world map depicting the New World; and Columbus's youngest brother Diego. The fleet stopped at the Canary Islands to take on more supplies, and set sail again on 7 October, deliberately taking a more southerly course than on the first voyage.

On 3 November, they arrived in the Windward Islands

french: Ãles du Vent

, image_name =

, image_caption = ''Political'' Windward Islands. Clockwise: Dominica, Martinique, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Grenada.

, image_alt =

, locator_map =

, location = Caribbean Sea No ...

; the first island they encountered was named Dominica

Dominica ( or ; Kalinago: ; french: Dominique; Dominican Creole French: ), officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, is an island country in the Caribbean. The capital, Roseau, is located on the western side of the island. It is geographical ...

by Columbus, but not finding a good harbor there, they anchored off a nearby smaller island, which he named ''Mariagalante'', now a part of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label= Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islandsâ Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La DÃĐsirade, and ...

and called Marie-Galante

Marie-Galante ( gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Mawigalant) is one of the islands that form Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of . It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 ...

. Other islands named by Columbus on this voyage were Montserrat

Montserrat ( ) is a British Overseas Territory in the Caribbean. It is part of the Leeward Islands, the northern portion of the Lesser Antilles chain of the West Indies. Montserrat is about long and wide, with roughly of coastline. It is n ...

, Antigua

Antigua ( ), also known as Waladli or Wadadli by the native population, is an island in the Lesser Antilles. It is one of the Leeward Islands in the Caribbean region and the main island of the country of Antigua and Barbuda. Antigua and Bar ...

, Saint Martin, the Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands ( es, Islas VÃrgenes) are an archipelago in the Caribbean Sea. They are geologically and biogeographically the easternmost part of the Greater Antilles, the northern islands belonging to the Puerto Rico Trench and St. Cro ...

, as well as many others.

On 22 November, Columbus returned to Hispaniola to visit La Navidad, where 39 Spaniards had been left during the first voyage. Columbus found the fort in ruins, destroyed by the TaÃnos after some of the Spaniards reportedly antagonized their hosts with their unrestrained lust for gold and women. Columbus then established a poorly located and short-lived settlement to the east, La Isabela

La Isabela in Puerto Plata Province, Dominican Republic was the first Spanish town in the Americas. The site is 42 km west of the city of Puerto Plata, adjacent to the village of El Castillo. The area now forms a National Historic Park.

...

, in the present-day Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, RepÚblica Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares with ...

.