Coronation Of George III And Charlotte on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

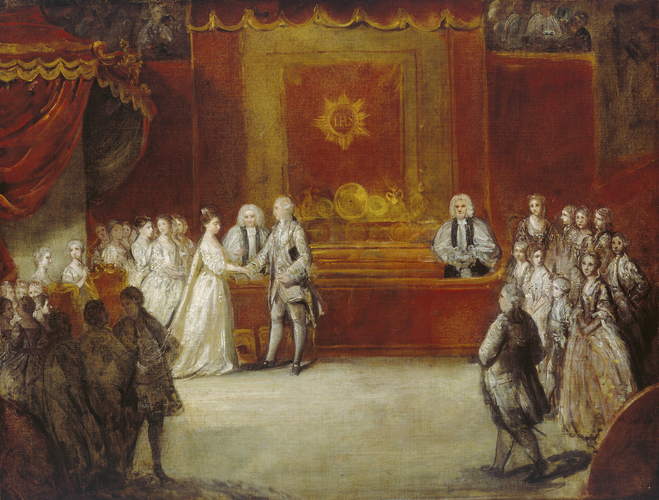

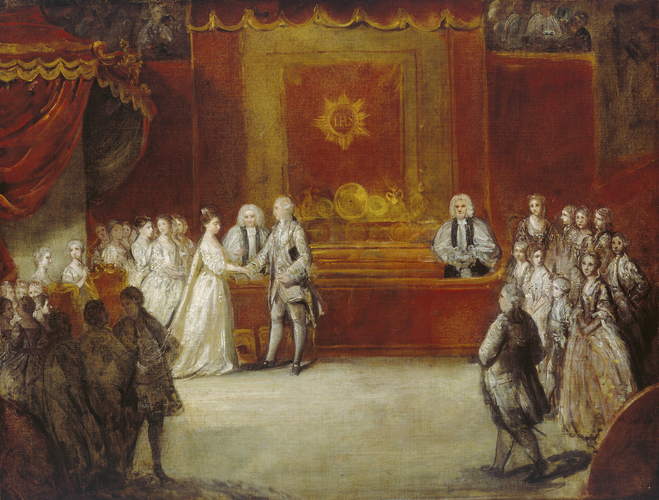

On the death of his grandfather, George II, George ascended to the throne on 25 October 1760 at the age of 22. The young king was yet to be married, and so he inquired Lord Bute on suitable Protestant German princesses to be his wife and consort. In July 1761, it was decided that the King would marry the 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom lacked interest in political affairs much to George's favour. After she arrived at St James's Palace accompanied by her brother, Duke Adolphus Frederick, on 8 September 1761 to meet the King, George and Charlotte were married at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace the same day. They were married just in time for the coronation ceremony two weeks later.

On the death of his grandfather, George II, George ascended to the throne on 25 October 1760 at the age of 22. The young king was yet to be married, and so he inquired Lord Bute on suitable Protestant German princesses to be his wife and consort. In July 1761, it was decided that the King would marry the 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom lacked interest in political affairs much to George's favour. After she arrived at St James's Palace accompanied by her brother, Duke Adolphus Frederick, on 8 September 1761 to meet the King, George and Charlotte were married at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace the same day. They were married just in time for the coronation ceremony two weeks later.

The coronation proved to be an anticipated affair, for the morning of the ceremony was marked with crowded streets as well as overflown inns, rooms, and homes waiting for the appearance of the new king and queen. Reportedly a great many carriages hastily arrived at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, many of them colliding in ensuing chaos. At around 9:00 am, George and Charlotte departed from St James's Palace and were carried separately to Westminster Hall in

The coronation proved to be an anticipated affair, for the morning of the ceremony was marked with crowded streets as well as overflown inns, rooms, and homes waiting for the appearance of the new king and queen. Reportedly a great many carriages hastily arrived at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, many of them colliding in ensuing chaos. At around 9:00 am, George and Charlotte departed from St James's Palace and were carried separately to Westminster Hall in

The coronation ceremony was conducted by Archbishop Secker. The first part of the ceremony, the recognition and oath, required the congregation to give their assent by shouting "God save King George", after which the king swore and signed the coronation oath. At this point, a brief 15-minute

The coronation ceremony was conducted by Archbishop Secker. The first part of the ceremony, the recognition and oath, required the congregation to give their assent by shouting "God save King George", after which the king swore and signed the coronation oath. At this point, a brief 15-minute

1761 is the only known coronation where almost all the music was written by the same composer,

1761 is the only known coronation where almost all the music was written by the same composer,

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

and his wife Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

as King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

and Queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel, the Irish Sea, and St George's Channel. Ireland is the s ...

took place at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, London, on Tuesday, 22 September 1761, about two weeks after they were married in the Chapel Royal

The Chapel Royal is an establishment in the Royal Household serving the spiritual needs of the sovereign and the British Royal Family. Historically it was a body of priests and singers that travelled with the monarch. The term is now also appl ...

, St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Alt ...

. The day was marked by errors and ommissions; a delayed procession from Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

to the abbey was followed by a six-hour coronation service and then a banquet that finally ended at ten o'clock at night.

Background

On the death of his grandfather, George II, George ascended to the throne on 25 October 1760 at the age of 22. The young king was yet to be married, and so he inquired Lord Bute on suitable Protestant German princesses to be his wife and consort. In July 1761, it was decided that the King would marry the 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom lacked interest in political affairs much to George's favour. After she arrived at St James's Palace accompanied by her brother, Duke Adolphus Frederick, on 8 September 1761 to meet the King, George and Charlotte were married at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace the same day. They were married just in time for the coronation ceremony two weeks later.

On the death of his grandfather, George II, George ascended to the throne on 25 October 1760 at the age of 22. The young king was yet to be married, and so he inquired Lord Bute on suitable Protestant German princesses to be his wife and consort. In July 1761, it was decided that the King would marry the 17-year-old Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom lacked interest in political affairs much to George's favour. After she arrived at St James's Palace accompanied by her brother, Duke Adolphus Frederick, on 8 September 1761 to meet the King, George and Charlotte were married at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace the same day. They were married just in time for the coronation ceremony two weeks later.

Preparations

The coronation was budgeted at £9,430 (some sources give a figure of around £70,000.) By tradition, ceremonial preparations ought to have been conducted by the hereditaryEarl Marshal

Earl marshal (alternatively marschal or marischal) is a hereditary royal officeholder and chivalric title under the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, sovereign of the United Kingdom used in England (then, following the Act of Union 1800, in the U ...

, Edward Howard, 9th Duke of Norfolk; however, being a Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

* Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a let ...

, he was debarred, and deputed the role to his distant relative, Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Effingham. The liturgy of the coronation service was the responsibility of the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Just ...

, Thomas Secker, who made only minimal changes from the previous service, mainly to accomodate the consort's coronation and to reflect the fact that Britain was in the course of fighting the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

with France.

The abbey building was transformed with numerous wooden galleries erected in the quire for Members of Parliament, ambassadors and musicians, while in the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-typ ...

, three tiers of galleries for the public were built into the arcade. Tickets for a front seat cost 10 guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

s (£10.50) each, while a higher box of twelve seats cost 50 guineas (£52.50). The builders boasted that they had damaged "a whole legion of angels" during the construction work.

Westminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

was also transformed, as it was generally divided by wooden partions into various courtroom

A courtroom is the enclosed space in which courts of law are held in front of a judge. A number of courtrooms, which may also be known as "courts", may be housed in a courthouse. In recent years, courtrooms have been equipped with audiovisual ...

s. A wooden floor was installed, along with three tiers of galleries for spectators. The highest of these was attached to the hammerbeams of the roof, while the lowest was fitted with a sluice "for the reception of urinary discharges". Over the north door, a triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road. In its simplest form a triumphal arch consists of two massive piers connected by an arch, cr ...

designed by William Oram

William Oram (Born circa 1711, died 1777) was an English painter and architect.

Life

Oram was educated as an architect, and, through the patronage of Sir Edward Walpole, obtained the position of master-carpenter to the Board of Works. He designe ...

was erected, surmounted by a balcony for musicians and a pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks' ...

. Illumination was provided by twenty-five huge chandelier

A chandelier (; also known as girandole, candelabra lamp, or least commonly suspended lights) is a branched ornamental light fixture designed to be mounted on ceilings or walls. Chandeliers are often ornate, and normally use incandescent ...

s. Outside, temporary stands giving a view of the procession between the hall and the abbey were erected by enterprising builders, some seating up to 1,500 people, while renting a house which overlooked the scene for the day, could cost up to £1,000.

Procession

The coronation proved to be an anticipated affair, for the morning of the ceremony was marked with crowded streets as well as overflown inns, rooms, and homes waiting for the appearance of the new king and queen. Reportedly a great many carriages hastily arrived at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, many of them colliding in ensuing chaos. At around 9:00 am, George and Charlotte departed from St James's Palace and were carried separately to Westminster Hall in

The coronation proved to be an anticipated affair, for the morning of the ceremony was marked with crowded streets as well as overflown inns, rooms, and homes waiting for the appearance of the new king and queen. Reportedly a great many carriages hastily arrived at Westminster Abbey on the day of the coronation, many of them colliding in ensuing chaos. At around 9:00 am, George and Charlotte departed from St James's Palace and were carried separately to Westminster Hall in sedan chair

The litter is a class of wheelless vehicles, a type of human-powered transport, for the transport of people. Smaller litters may take the form of open chairs or beds carried by two or more carriers, some being enclosed for protection from the e ...

s, where invited nobility, government officials and members of the royal household had gathered.

Following ancient tradition, the assembled participants in the hall awaited the arrival of a procession of senior clergy from the abbey bearing the crowns and regalia; these were then distributed to those who had the right to carry them in the main procession from the hall to the abbey. On this occasion, there was a lengthy delay because the deputy earl marshal had forgotten some important items; no chairs had been provided for the king and queen, there was no sword of state, so one had to be borrowed from the Lord Mayor of London

The Lord Mayor of London is the mayor of the City of London and the leader of the City of London Corporation. Within the City, the Lord Mayor is accorded precedence over all individuals except the sovereign and retains various traditional pow ...

, and also there was no canopy under which the king and queen were supposed to process and one had to be improvised.

The short procession on foot between Westminster Hall and Westminster Abbey was the only part of the ceremonial to be visible to the general public and a huge crowd filled not only the pavements but also the windows and rooves of the surrounding houses, as well as specially built wooden grandstand

A grandstand is a normally permanent structure for seating spectators. This includes both auto racing and horse racing. The grandstand is in essence like a single section of a stadium, but differs from a stadium in that it does not wrap al ...

s. The route ran from New Palace Yard, along Parliament Street, Bridge Street and King Street to the west door of the abbey, along which a temporary wooden walkway had been constructed, high and wide so that the participants could be seen more easily. However, the 2,800 soldiers standing on either side obstructed the view and they had to beat back the eager crowds with the flat side of their swords and the butts of their muskets. The King and Queen entered the Abbey shortly after 1:30 p.m., with the dignity of the royal couple and the “reverent attention which both paid to the service” being favourably commented on. The procession and ceremony were so long the King was not crowned until 3:30 that afternoon.

Service

The coronation ceremony was conducted by Archbishop Secker. The first part of the ceremony, the recognition and oath, required the congregation to give their assent by shouting "God save King George", after which the king swore and signed the coronation oath. At this point, a brief 15-minute

The coronation ceremony was conducted by Archbishop Secker. The first part of the ceremony, the recognition and oath, required the congregation to give their assent by shouting "God save King George", after which the king swore and signed the coronation oath. At this point, a brief 15-minute sermon

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. ...

was given by the Bishop of Salisbury

The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset. The see is in the City of Salisbury where the bishop's seat ...

, Robert Hay Drummond (some sources incorrectly state that it was given by the archbishop). Then followed the anointing

Anointing is the ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body.

By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, or ot ...

with holy oil, the investing

Investment is the dedication of money to purchase of an asset to attain an increase in value over a period of time. Investment requires a sacrifice of some present asset, such as time, money, or effort.

In finance, the purpose of investing i ...

with the regalia and at the climax of the ceremony, crowned king of Great Britain and Ireland by the archbishop. This point in the service was reached at 3.30 pm; it was accompanied by trumpet fanfare

A fanfare (or fanfarade or flourish) is a short musical flourish which is typically played by trumpets, French horns or other brass instruments, often accompanied by percussion. It is a "brief improvised introduction to an instrumental perf ...

s in the abbey and a man perched high on the roof gave a signal for the firing of gun salute

A gun salute or cannon salute is the use of a piece of artillery to fire shots, often 21 in number (''21-gun salute''), with the aim of marking an honor or celebrating a joyful event. It is a tradition in many countries around the world.

Histo ...

s in Green Park and on the other side of the city at the Tower of London. The enthronement and homage saw each of the peers in turn pledge their loyalty, during which, gold and silver coronation medallion

A medal or medallion is a small portable artistic object, a thin disc, normally of metal, carrying a design, usually on both sides. They typically have a commemorative purpose of some kind, and many are presented as awards. They may be int ...

s were scattered amongst the congregation. This was followed by the queen's briefer crowning and finally the king and queen received Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

. After changing out of their ceremonial robes, the king, queen nobles and bishops processed back to Westminster Hall in the same order in which they had come; the service had lasted six hours and it was dark by the time that they left the abbey.

Mishaps

On the way to the abbey, theBishop of Rochester

The Bishop of Rochester is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Rochester in the Province of Canterbury.

The town of Rochester has the bishop's seat, at the Cathedral Church of Christ and the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was fo ...

nearly dropped the crown he was carrying; fortunately it had been pinned to the cushion that it sat on. One spectator noted that the herald

A herald, or a herald of arms, is an officer of arms, ranking between pursuivant and king of arms. The title is commonly applied more broadly to all officers of arms.

Heralds were originally messengers sent by monarchs or noblemen to ...

s made "numerous mistakes and stupidities", another that "the whole was confusion, irregularity and disorder". The King felt it inappropriate to take Communion wearing his crown, and asked the archbishop if it should be removed, the archbishop in turn asked the Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the Abbey's status as a Royal Peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterbu ...

, but had to report that neither knew what the usual form was; the king removed his crown anyway. At some point in the procedings, a large jewel is reputed to have fallen from the crown, which was later said to have been an omen presaging American Independence

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. During the sermon, the congregation in the nave who were unable to hear it, began to eat, mainly cold meat and pies, and drink wine brought with them and given out by servants; the ensuing clatter of cutlery resulted in an outburst of laughter. When the queen wanted to visit the "retiring-chamber" which had been constructed for her use in St Edward's Chapel behind the high altar, she found it already occupied by the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle ...

who was making use of the queen's close stool. When the king complained to Effingham about these problems, he admitted that there had been "some neglect", but that he would make sure that the ''next'' coronation would be organised properly (when of course, the king would be dead). George was highly amused by the answer and made Effingham repeat it several times.

Music

1761 is the only known coronation where almost all the music was written by the same composer,

1761 is the only known coronation where almost all the music was written by the same composer, William Boyce William Boyce may refer to:

* William Boyce (composer) (1711–1779), English-born composer and Master of the King's Musick

* William Binnington Boyce (1804–1889), English-born philologist and clergyman, active in Australia

*William Waters Boyce ...

, who was the Master of the King's Music. Boyce believed, probably incorrectly, that he had been commissioned to write new musical setting A musical setting is a musical composition that is written on the basis of a literary work. The literary work is said to be ''set'', or adapted, to music. Musical settings include choral music and other vocal music. A musical setting is made to ...

s for all of the traditional coronation texts. Although he completed eight choral pieces for the service, he wrote to Archbishop Secker declining to rewrite the music for the anthem ''Zadok the Priest

''Zadok the Priest'' ( HWV 258) is a British anthem that was composed by George Frideric Handel for the coronation of King George II in 1727. Alongside '' The King Shall Rejoice'', '' My Heart is Inditing'' and '' Let Thy Hand Be Strengthened' ...

'' because "it cannot be more properly set than it has already been by Mr. Handel" (Handel had written four of the anthems at the previous coronation). The archbishop wrote back to say that the king had agreed, and Handel's setting of ''Zadok'' has been used at every coronation since. Boyce's setting of the entrance anthem, ''I was glad

"I was glad" (Latin incipit, "Laetatus sum") is a choral introit which is a popular piece in the musical repertoire of the Anglican church. It is traditionally sung in the Church of England as an anthem at the Coronation of the British monarch.

...

'', was probably sung in two parts to allow the boys of Westminster School

(God Gives the Increase)

, established = Earliest records date from the 14th century, refounded in 1560

, type = Public school Independent day and boarding school

, religion = Church of England

, head_label = Hea ...

to shout their traditional '' Vivat!'' acclamation.

The combined choirs of Westminster Abbey and the Chapel Royal probably numbered 42 singers and there was an orchestra of about 105 musicians. The choir was arranged in the front rows of the galleries that had been erected in the eastern end of the abbey, with the orchestra in a gallery over the rood screen

The rood screen (also choir screen, chancel screen, or jubé) is a common feature in late medieval church architecture. It is typically an ornate partition between the chancel and nave, of more or less open tracery constructed of wood, stone, o ...

. Boyce asked for the top of the tall reredos

A reredos ( , , ) is a large altarpiece, a screen, or decoration placed behind the altar in a church. It often includes religious images.

The term ''reredos'' may also be used for similar structures, if elaborate, in secular architecture, for e ...

of the high altar to be dismantled so that all the choristers could see the conductor, but even so, an assistant conductor was required. The music seems to be the only element of the coronation to have gone without a hitch, perhaps because Boyce held three full rehearsals in the abbey, to which the public were admitted by ticket, the last being on the day before the service.

Banquet

The ceremony ended with a coronation banquet, theLord Steward

The Lord Steward or Lord Steward of the Household is an official of the Royal Household in England. He is always a peer. Until 1924, he was always a member of the Government. Until 1782, the office was one of considerable political importance a ...

, the Lord High Constable and the Deputy Earl Marshall presided on horseback. The distinguished diners had to sit in the dark until, on the entry of the king and queen, all 3,000 candles were lit almost at once by means of a network of linen tapers, which while spectacular, showered the guest with flakes of ash..

Here again, poor organisation came into play, much of the blame for which attached to the Lord Steward, William Talbot, Earl Talbot, a boxing enthusiast who was noted for his "swaggering manners and rude demeanour". No tables were provided for the Barons of the Cinque Ports and the Aldermen of the City of London

An alderman is a member of a municipal assembly or council in many jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council member chosen by the elected members ...

, who ought to have had prominent places set for them. The aldermen were given the table of the Knights of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved bathing (as a symbol of purification) as on ...

, who in turn displaced the Great Officers of State

Government in medieval monarchies generally comprised the king's companions, later becoming the Royal Household, from which the officers of state arose, initially having household and government duties. Later some of these officers became ...

. The unfortunate Cinque Port barons were only silenced by Talbot challenging them to a duel. Talbot had carefully trained his horse to walk backwards away from the thrones, however the horse could not be prevented from repeatedly entering the hall backwards with its hindquarters towards the king, causing much mirth among the onlookers.

Between the first and second courses, the hereditary King's Champion, John Dymoke, entered the hall in full armour, allegedly mounted on the same grey horse that King George II had ridden at the Battle of Dettingen eighteen years earlier. Spectators reportedly let down baskets and handkerchiefs to the eaters at the banquet tables below, who would send up chicken and wine. The banquet finally ended at 10 pm when the king and queen left in their sedan chairs; as tradition demanded, the doors of the hall were then thrown open to the public, who carried off anything that had been left behind, including plates, cutlery and table cloths.

Royal guests

* The Dowager Princess of Wales, ''the King's mother'' ** The Duke of York and Albany, ''the King's brother'' * The Duke of Cumberland, ''the King's paternal uncle''Other celebrations

In London, large crowds celibrated in the streets. Although thePrivy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mo ...

had forbidden bonfire

A bonfire is a large and controlled outdoor fire, used either for informal disposal of burnable waste material or as part of a celebration.

Etymology

The earliest recorded uses of the word date back to the late 15th century, with the Catho ...

s to be lit on coronation night for safety reasons, this seems to have been widely ignored, despite the patrolling troops of cavalry. The Secretary of State, the Duke of Newcastle

Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne was a title that was created three times, once in the Peerage of England and twice in the Peerage of Great Britain. The first grant of the title was made in 1665 to William Cavendish, 1st Marquess of Newcastle ...

, had one lit outside his London home and gave away beer to the crowds, while others illuminated their houses with lanterns. Elsewhere, Coronation Day was marked by thanksgiving services in churches, civic banquets, fireworks and feasts laid on for the poor by wealthy benefactors. In the following weeks the theatres in the West End of London

The West End of London (commonly referred to as the West End) is a district of Central London, west of the City of London and north of the River Thames, in which many of the city's major tourist attractions, shops, businesses, government build ...

staged elaborate recreations of the coronation; the show at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, commonly known as Drury Lane, is a West End theatre and Grade I listed building in Covent Garden, London, England. The building faces Catherine Street (earlier named Bridges or Brydges Street) and backs onto Dr ...

ended with "a real bonfire and a real mob" on stage, while the production at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden featured the actual choir of Westminster Abbey.Strong 2005, p. 415

References

Sources

* * * * * * * {{Ceremonies of the British monarch 1761 in England 1760s in London 18th century in the City of Westminster George III and Charlotte George III of the United Kingdom Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz