Convoys in World War I on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

The

The Germans again responded by changing strategy and concentrating on the Mediterranean theater, where the extremely limited use of convoys had been approved at the Corfu Conference (28 April–1 May 1916).William P. McEvoy and Spencer C. Tucker, "Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations (1914–1918)", ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History'', Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 774–77. The Mediterranean proved a more difficult zone for convoying than the Atlantic, because its routes were more complex and the entire sea was considered a danger zone (like British home waters). There the escorts were not provided only by Britain. The French Navy, U.S. Navy, Imperial Japanese Navy, ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Italian Navy) and

The Germans again responded by changing strategy and concentrating on the Mediterranean theater, where the extremely limited use of convoys had been approved at the Corfu Conference (28 April–1 May 1916).William P. McEvoy and Spencer C. Tucker, "Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations (1914–1918)", ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History'', Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 774–77. The Mediterranean proved a more difficult zone for convoying than the Atlantic, because its routes were more complex and the entire sea was considered a danger zone (like British home waters). There the escorts were not provided only by Britain. The French Navy, U.S. Navy, Imperial Japanese Navy, ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Italian Navy) and

Sea Transport and Supply

, in

Atlantic operations of World War I Baltic Sea operations of World War I Mediterranean naval operations of World War I North Sea operations of World War I U-boat Campaign (World War I)

The

The convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

—a group of merchantmen

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are us ...

or troopships traveling together with a naval

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It includ ...

escort—was revived during World War I (1914–18), after having been discarded at the start of the Age of Steam. Although convoys were used by the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

in 1914 to escort troopships from the Dominions, and in 1915 by both it and the French Navy to cover their own troop movements for overseas service, they were not systematically employed by any belligerent navy until 1916. The Royal Navy was the major user and developer of the modern convoy system, and regular transoceanic convoying began in June 1917. They made heavy use of aircraft

An aircraft is a vehicle that is able to fly by gaining support from the air. It counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines. ...

for escorts, especially in coastal waters, an obvious departure from the convoy practices of the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid- 15th) to the mid- 19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the introduction of naval ...

.

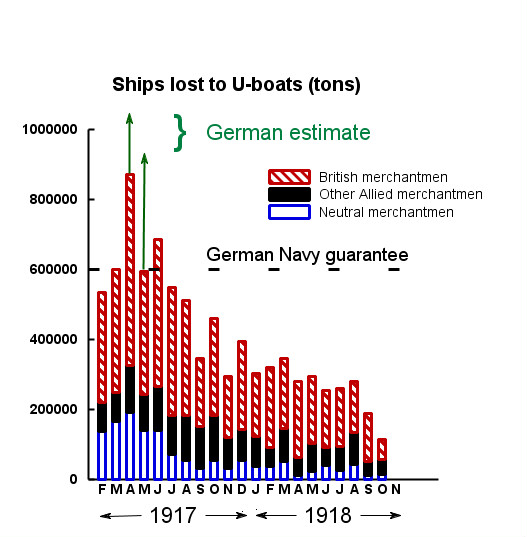

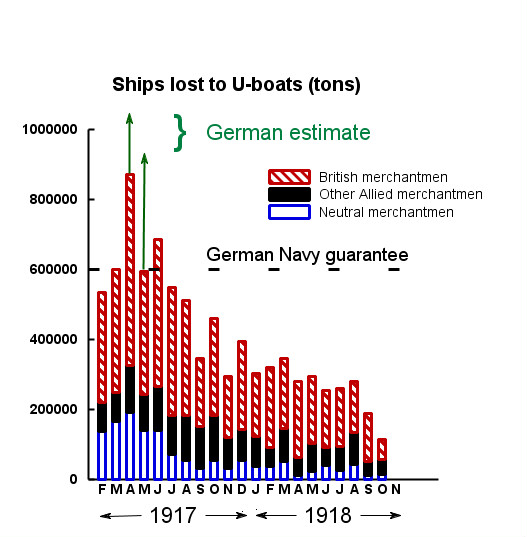

As historian Paul E. Fontenoy put it, " e convoy system defeated the German submarine campaign."Paul E. Fontenoy, "Convoy System", ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History'', Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker

Spencer C. Tucker is a Fulbright scholar, retired university professor, and author of works on military history. He taught history at Texas Christian University for 30 years and held the John Biggs Chair of Military History at the Virginia Milita ...

, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 312–14. From June 1917 on, the Germans were unable to meet their set objective of sinking of enemy shipping per month. In 1918, they were rarely able to sink more than . Between May 1917 and the end of the war on 11 November 1918, only 154 of 16,539 vessels convoyed across the Atlantic had been sunk, of which 16 were lost through the natural perils of sea travel and a further 36 because they were stragglers.

Development

Origins

The first large convoy of the war was theAustralian and New Zealand Army Corps

The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) was a First World War army corps of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force. It was formed in Egypt in December 1914, and operated during the Gallipoli campaign. General William Birdwood comma ...

(ANZAC) convoy. On 18 October 1914, the Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

left the port of Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

, New Zealand, with 10 troopships. They joined 28 Australian ships and the Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Au ...

light cruisers and '' Melbourne'' at Albany, Western Australia. The Japanese also sent the cruiser to patrol the Indian Ocean during the convoy's crossing to Aden

Aden ( ar, عدن ' Yemeni: ) is a city, and since 2015, the temporary capital of Yemen, near the eastern approach to the Red Sea (the Gulf of Aden), some east of the strait Bab-el-Mandeb. Its population is approximately 800,000 people. ...

. During the crossing, HMAS ''Sydney'' was caught up in the Battle of Cocos

The Battle of Cocos was a single-ship action that occurred on 9 November 1914, after the Australian light cruiser , under the command of John Glossop, responded to an attack on a communications station at Direction Island by the German light c ...

(9 November), but the Japanese-escorted convoy reached Aden on 25 November. The Japanese continued to escort ANZAC convoys throughout the war. The convoys of Dominion troops were, weather permitting, escorted into port by airships

An airship or dirigible balloon is a type of aerostat or lighter-than-air aircraft that can navigate through the air under its own power. Aerostats gain their lift from a lifting gas that is less dense than the surrounding air.

In early ...

.John J. Abbatiello, ''Anti-submarine Warfare in World War I: British Naval Aviation and the Defeat of the U-boats'' (Oxford: Routledge, 2006), 109–11.

With the advent of commerce raiding

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

by the submarines of the Royal Navy, the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from ...

, and the '' Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial German Navy), it was neutral Sweden

Swedish neutrality refers to Sweden's former policy of neutrality in armed conflicts, which was in effect from the early 19th century to 2009, when Sweden entered into various mutual defence treaties with the European Union (EU), and other Nordic ...

, at the insistence of Germany, that first used a convoy system in early November 1915 to protect its own merchant shipping after the British and the Russians attacked its iron ore shipments to Germany. The German merchant fleet proposed a similar expedient, but the navy refused. However, in April 1916, Admiral Prince Heinrich of Prussia—commander-in-chief in the Baltic theater—approved regular scheduled escorts for German ships to Sweden. Losses to enemy submarines were drastically cut from the level of the previous year, and only five freighters were lost before the war's end. In June 1916, the Baltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

attacked a German convoy in the Bråviken, destroying the Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

Schiff H and some Swedish merchantmen, before mistakes by the commander of the Destroyer Division—Aleksandr Vasiliyevich Kolchak

Alexander Vasilyevich Kolchak (russian: link=no, Александр Васильевич Колчак; – 7 February 1920) was an Imperial Russian admiral, military leader and polar explorer who served in the Imperial Russian Navy and fought ...

—allowed the majority of the convoy to escape back to Norrköping.

Revival

To cover trade with the neutral Netherlands, the British instituted their first regular convoy on 26 July 1916, from theHook of Holland

Hook of Holland ( nl, Hoek van Holland, ) is a town in the southwestern corner of Holland, hence the name; ''hoek'' means "corner" and was the word in use before the word ''kaap'' – "cape", from Portuguese ''cabo'' – became Dutch. The English t ...

to Harwich, a route targeted by the German U-boats

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare rol ...

based out of Flanders. Only one straggler was lost before the Germans announced unrestricted submarine warfare on 1 February 1917, and only six after that before the war's end despite 1,861 sailings. The Holland convoys were sometimes referred to as the "Beef Trip" on account of the large proportion of food transported. They were escorted by destroyers of the Harwich Force

The Harwich Force originally called Harwich Striking Force was a squadron of the Royal Navy, formed during the First World War and based in Harwich. It played a significant role in the war.

History

After the outbreak of the First World War, a ...

and, later in the war, by AD Flying Boat

The AD Flying Boat was designed by the British Admiralty's Air Department to serve as a patrol aircraft that could operate in conjunction with Royal Navy warships. Intended for use during the First World War, production of the aircraft was term ...

s based out of Felixstowe

Felixstowe ( ) is a port town in Suffolk, England. The estimated population in 2017 was 24,521. The Port of Felixstowe is the largest container port in the United Kingdom. Felixstowe is approximately 116km (72 miles) northeast of London.

H ...

.

The first convoys to sail after the German announcement were requested by the French Navy, desirous of defending British coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dead ...

shipments. The Royal Navy's first coal convoy crossed the Channel on 10 February. These convoys were more weakly escorted, and contained a mixture of both steam-powered ships and sailing ships, as well as escorting aircraft based on the coast. In all, only 53 ships were lost in 39,352 sailings. When shippers from Norway (the "neutral ally") requested convoys in 1916 after a year of very serious losses, but refused to accept the routes chosen by the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

, they were declined. After the German proclamation, the Norwegians accepted British demands and informal convoying began in late January or February 1917, but regular convoys did not begin until 29 April. That same day, the first coastal convoy left Lerwick in the Shetland Islands

Shetland, also called the Shetland Islands and formerly Zetland, is a subarctic archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands and Norway. It is the northernmost region of the United Kingdom.

The islands lie about to the no ...

, the destination of the Norwegian convoys, for the Humber. This was to become a regular route. The Norwegian and coastal convoys included airships based out of Scotland (and in the latter case also Yorkshire).

Although the British War Cabinet proposed convoys in March 1917, the Admiralty still refused. It was not until of shipping were lost to U-boats in April (and British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

grain reserves had dropped to a six-week supply) that the Admiralty approved convoying all shipments coming through the north and south Atlantic. Rear Admiral Alexander Duff, head of the Antisubmarine Division, suggested it on 26 April, and the First Sea Lord, Admiral John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutland ...

, approved it the next day. Escorts were to be composed of obsolete cruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

s, armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

s and pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, protec ...

s for the oceanic portion of the routes, while in the more dangerous waters around Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

they were composed of destroyers. Observation balloons, especially kytoon

A kytoon or kite balloon is a tethered aircraft which obtains some of its lift dynamically as a heavier-than-air kite and the rest aerostatically as a lighter-than-air balloon. The word is a portmanteau of kite and balloon.

The primary advantage ...

s, were used to help spot submarines beneath the surface, the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for Carrier-based aircraft, carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a ...

not then being developed. During discussions in March, it was determined that 75 destroyers were needed, but only 43 were available. The first experimental convoy of merchant vessels left Gibraltar

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibra ...

on 10 May 1917 and arrived at the Downs on 22 May, having been accompanied by the last leg of its journey by a flying boat from the Scillies.

Maturation

The first transatlantic convoy leftHampton Roads

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James River, James, Nansemond River, Nansemond and Elizabeth River (Virginia), Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's ...

on 24 May escorted by the armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a battleship and fast en ...

, met up with eight destroyers from Devonport on 6 June, and brought all its ships save one straggler that was torpedoed, into their respective ports by 10 June. The first regular convoy left Hampton Roads on 15 June, the next left Sydney, Nova Scotia

Sydney is a former city and urban community on the east coast of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada within the Cape Breton Regional Municipality. Sydney was founded in 1785 by the British, was incorporated as a city in 1904, and dissol ...

on 22 June, and another left New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* ...

for the first time on 6 July. The Sydney convoy had to be diverted to Halifax during winter months. The first regular convoy from the south Atlantic commenced on 31 July. Fast convoys embarked from Sierra Leone—a British protectorate—while slow ones left from Dakar in French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burkin ...

. Gibraltar convoys became regular starting on 26 July.

Losses in convoy dropped to ten percent of those suffered by independent ships. Confidence in the convoy system grew rapidly in the summer of 1917, especially as it was realised that the ratio of merchant vessels to warship could be higher than previously thought. While the first convoys comprised 12 ships, by June they contained 20, which was increased to 26 in September and 36 in October. The U.S. Navy's liaison to Britain—Rear Admiral William Sims

William Sowden Sims (October 15, 1858 – September 28, 1936) was an admiral in the United States Navy who fought during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to modernize the navy. During World War I, he commanded all United States naval force ...

—and its ambassador—Walter H. Page

Walter Hines Page (August 15, 1855 – December 21, 1918) was an American journalist, publisher, and diplomat. He was the United States ambassador to the United Kingdom during World War I.

He founded the ''State Chronicle'', a newspaper in Ral ...

—were both strong supporters of convoying and opponents of Germany's unrestricted submarine warfare. Shortly after the U.S. entered the war, Sims brought over 30 destroyers to the waters around Britain to make up the Royal Navy's deficit.

The success of the convoys forced the German U-boats in the Atlantic to divert their attention from inbound shipping to outbound. In response, the first outbound convoy left for Hampton Roads on 11 August 1917. It was followed by matching outbound convoys for each regular route. These were escorted by destroyers as they left Britain and were taken over by the typical cruiser flotillas as they entered the open ocean.

The Germans again responded by changing strategy and concentrating on the Mediterranean theater, where the extremely limited use of convoys had been approved at the Corfu Conference (28 April–1 May 1916).William P. McEvoy and Spencer C. Tucker, "Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations (1914–1918)", ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History'', Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 774–77. The Mediterranean proved a more difficult zone for convoying than the Atlantic, because its routes were more complex and the entire sea was considered a danger zone (like British home waters). There the escorts were not provided only by Britain. The French Navy, U.S. Navy, Imperial Japanese Navy, ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Italian Navy) and

The Germans again responded by changing strategy and concentrating on the Mediterranean theater, where the extremely limited use of convoys had been approved at the Corfu Conference (28 April–1 May 1916).William P. McEvoy and Spencer C. Tucker, "Mediterranean Theater, Naval Operations (1914–1918)", ''The Encyclopedia of World War I: A Political, Social and Military History'', Volume 1, Spencer C. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 774–77. The Mediterranean proved a more difficult zone for convoying than the Atlantic, because its routes were more complex and the entire sea was considered a danger zone (like British home waters). There the escorts were not provided only by Britain. The French Navy, U.S. Navy, Imperial Japanese Navy, ''Regia Marina'' (Royal Italian Navy) and Brazilian Navy

)

, colors= Blue and white

, colors_label= Colors

, march= " Cisne Branco" ( en, "White Swan") (same name as training ship '' Cisne Branco''

, mascot=

, equipment= 1 multipurpose aircraft carrier7 submarines6 frigates2 corvettes4 amphibious warf ...

all contributed. The first routes to receive convoy protection were the coal route from Egypt to Italy via Bizerte

Bizerte or Bizerta ( ar, بنزرت, translit=Binzart , it, Biserta, french: link=no, Bizérte) the classical Hippo, is a city of Bizerte Governorate in Tunisia. It is the northernmost city in Africa, located 65 km (40mil) north of the cap ...

, French Tunisia, and that between southern metropolitan France and French Algeria. The U.S. took responsibility for the ingoing routes to Gibraltar

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibra ...

, and increasingly for most of the eastern Mediterranean. The commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, Somerset Calthorpe, began introducing the convoy system for the route from Port Said to Britain in mid-October 1917. Calthorpe remained short of escorts and was unable to cover all Mediterranean trade, but his request to divert warships from convoy duty to the less effective Otranto Barrage

The Otranto Barrage was an Allied naval blockade of the Otranto Straits between Brindisi in Italy and Corfu on the Greek side of the Adriatic Sea in the First World War. The blockade was intended to prevent the Austro-Hungarian Navy from esca ...

was denied by the Admiralty.

With the gradual success of the Mediterranean convoys, the Germans began to concentrate on attacking shipping in Britain's coastal waters, as convoyed vessels dispersed to their individual ports. Coastal convoy routes were only added gradually due to the limited availability of escorts, but by the end of the war almost all sea traffic in the war zones was convoyed. The coastal convoys relied heavily on air support. After June 1918, almost all convoys were escorted in part by land-based airplane

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spectr ...

s and airships, as well as sea plane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of taking off and landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their technological characterist ...

s. The organisation of these convoys had also been delegated by the Admiralty to local commanders.

Admiralty resistance and objections

The main objection of the Admiralty to providing escorts for merchant shipping (as opposed to troop transits) was that it did not have sufficient forces. In large part, this was based on miscalculation. The Admiralty's estimates of the number of vessels requiring escort and the number of escorts required per convoy—it mistakenly assumed a 1:1 ratio between escorts and merchant vessels—were both wrong. The former error was exposed by Commander R. G. H. Henderson of the Antisubmarine Division and Norman Leslie of the Ministry of Shipping, who showed that the Admiralty was relying on customs statistics that counted each arrival and departure, concluding that 2,400 vessels a week, translating into 300 ships a day, required an escort. In fact, there were only 140 ships per week, or 20 per day, on transoceanic voyages. But the manageability of the task was not the Admiralty's only objection. It alleged that convoys presented larger and easier targets to U-boats, and harder object to defend by the Navy, raising the danger of the submarine threat rather than lowering it. It cited the difficulty of coordinating a rendezvous, which would lead to vulnerability while the merchant ships were in the process of assembling, and a greater risk of mines. The Admiralty also showed a distrust of the merchant skippers: they could not manoeuvre in company, especially considering that the ships would have various top speeds, nor could they be expected to keep station. At a conference in February 1917, some merchant captains raised the same concerns. Finally, the Admiralty suggested that a large number of merchantmen arriving simultaneously would be too much tonnage for the ports to handle, but this, too, was based in part on the miscalculation. In light of the cult of the offensive, the convoy was also dismissed as "defensive". In fact, it reduced the number of available targets for U-boats, forcing them to attack well-defended positions and usually giving them only a single chance, since the escorting warships would respond with a counterattack. It also "narrowed to the least possible limits he area in which the submarine is to be hunted, according to the ''Anti-Submarine Report'' of theRoyal Navy Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps t ...

(RNAS) of December 1917. In that month, the First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

— Eric Geddes—removed Admiral Jellicoe from his post of First Sea Lord because of the latter's opposition to the convoy system, which Prime Minister David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during ...

had appointed Geddes to implement.

Organisation

Types of convoy

According to John Abbatiello, there were four categories of convoy used during World War I. The first category consists of the short-distance convoys, such as those between Britain and its European allies, and between Britain and neutral countries. The commercial convoys between England and the Netherlands or Norway are examples, as are the coal convoys between England and France. The second category consists of the escorts of warships, usually troopships, such as those from the Dominions in the early stages of the war. These formed the earliest convoys, but "probably the most overlooked category". The British Grand Fleet itself could be included in this category, since it was always escorted by a destroyer screen in the North Sea and frequently by long-range ''Coastal'' and ''North Sea''-class airships. The third category is the so-called "ocean convoys" that safeguarded transoceanic commerce. They traversed the Atlantic from the U.S. or Canada in the north, or from British or French colonial Africa or Gibraltar in the south. The fourth category is the "coastal convoys", those protecting trade and ship movements along the coast of Britain and within British home waters. Most coastal and internal sea traffic was not convoyed until mid-1918. These convoys involved the heavy use of aircraft.Structure of command

With the success of the convoy system, the Royal Navy created a new Convoy Section and a Mercantile Movements Division at the Admiralty to work with the Ministry of Shipping and the Naval Intelligence Division to organise convoys, routings and schedules. Before this, the Norwegian convoys, coal convoys and Beef Trip convoys had often been arranged by local commanders. The Admiralty arranged the rendezvous, decided which ships would be escorted and in what order they would sail, but it left the composition of the escort itself to theCommander-in-Chief, Plymouth

The Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, was a senior commander of the Royal Navy for hundreds of years. Plymouth Command was a name given to the units, establishments, and staff operating under the admiral's command. Between 1845 and 1896, this offic ...

. The wing captain of the Southwest Air Group also received notification of the Admiralty's convoys, and provided air cover as they approached their ports. The Enemy Submarine and Direction Finding Section and the code-breakers of Room 40 cooperated to give the convoy planners knowledge U-boat movements.

With the advent of coastal convoys, escort composition and technique fell into the hands of the district commanders-in-chief.Abbatiello (2006), 108.

Use of aircraft

In April 1918, the airship ''NS-3'' escorted a convoy for 55 hours, including patrols at night both with and without moonlight. In complete darkness the airship had to stay behind the ships and follow their stern lights. The only value in such patrols was in maximising useful daylight hours by having the airships already aloft at dawn. In July, the Antisubmarine Division and theAir Department

The Air Department of the British Admiralty later succeeded briefly by the Air Section followed by the Air Division was established prior to World War I by Winston Churchill to administer the Royal Naval Air Service.

History

In 1908, the Brit ...

of the Admiralty considered and rejected the use of searchlights during night, believing the airships would render themselves vulnerable to surfaced U-boats. Testing of searchlights on aircraft revealed that the bomb payload needed to be much reduced to accommodate searchlight systems. Parachute flares offered better illumination (and were less illuminating of the airships′ positions), but they weighed in at 80 pounds each, making them too costly to drop unless the rough position of the enemy was already known. The Admiralty restricted the use of lights on airships for recognition, emergencies and under orders from senior naval officers only.

Of the 257 ships sunk by submarines from World War I convoys, only five were lost while aircraft assisted the surface escort. On 26 December 1917, as an airship was escorting three merchantmen out of Falmouth for their rendezvous with a convoy, they were attacked three times in the space of 90 minutes, torpedoing and sinking two of the vessels and narrowly missing the third before escaping. The airship had been away at the time of the incident, which was one of the last of its kind. In 1918, U-boats attacked convoys escorted by both surface ships and aircraft only six times, sinking three ships in total out of thousands. Because of the decentralised nature of the convoy system, the RNAS had no say in the composition or use of air escorts. The northeast of England led the way in the use of aircraft for short- and long-range escort duty, but shore-based aerial "hunting patrols" were widely considered a superior use of air resources. Subsequent historians have not agreed, although they have tended to overstress the actual use made of aircraft in convoy escort duty. An Admiralty staff study in 1957 concluded that the convoy was the best defence against enemy attacks on shipping, and dismissed shore-based patrols while commending the use of air support in convoying.For a revised edition of the staff study, cf. Freddie Barley and David Waters (eds.), ''The Defeat of the Enemy Attack of Shipping, 1939–45'' (Aldershot: Ashgate for The Navy Records Society, 1997). Barley and Waters conclusions about hunting patrols ''vis-à-vis'' convoys were followed by Arthur Marder

Arthur Jacob Marder (8 March 1910 – 25 December 1980) was an American historian specializing in British naval history in the period 1880–1945.

Early life and education

Born and raised in Boston, Massachusetts, Arthur Marder was the son of Max ...

, ''From Dreadnought to Scapa Flow'', 5 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961–70), quoted in Abbatiello (2006), 82.

Notes

{{Reflist, 2External links

* Miller B., MichaelSea Transport and Supply

, in

Atlantic operations of World War I Baltic Sea operations of World War I Mediterranean naval operations of World War I North Sea operations of World War I U-boat Campaign (World War I)