Congress of Vienna on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor

The name "Congress of Vienna" was not meant to suggest a formal

The name "Congress of Vienna" was not meant to suggest a formal

The Congress functioned through formal meetings such as working groups and official diplomatic functions; however, a large portion of the Congress was conducted informally at salons, banquets, and balls.

The Congress functioned through formal meetings such as working groups and official diplomatic functions; however, a large portion of the Congress was conducted informally at salons, banquets, and balls.

''The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity: 1812–1822''

Grove Press; Rep. Ed. pp. 140–164. When the Tsar heard of the treaty he agreed to a compromise that satisfied all parties on 24 October 1815. Russia received most of the Napoleonic

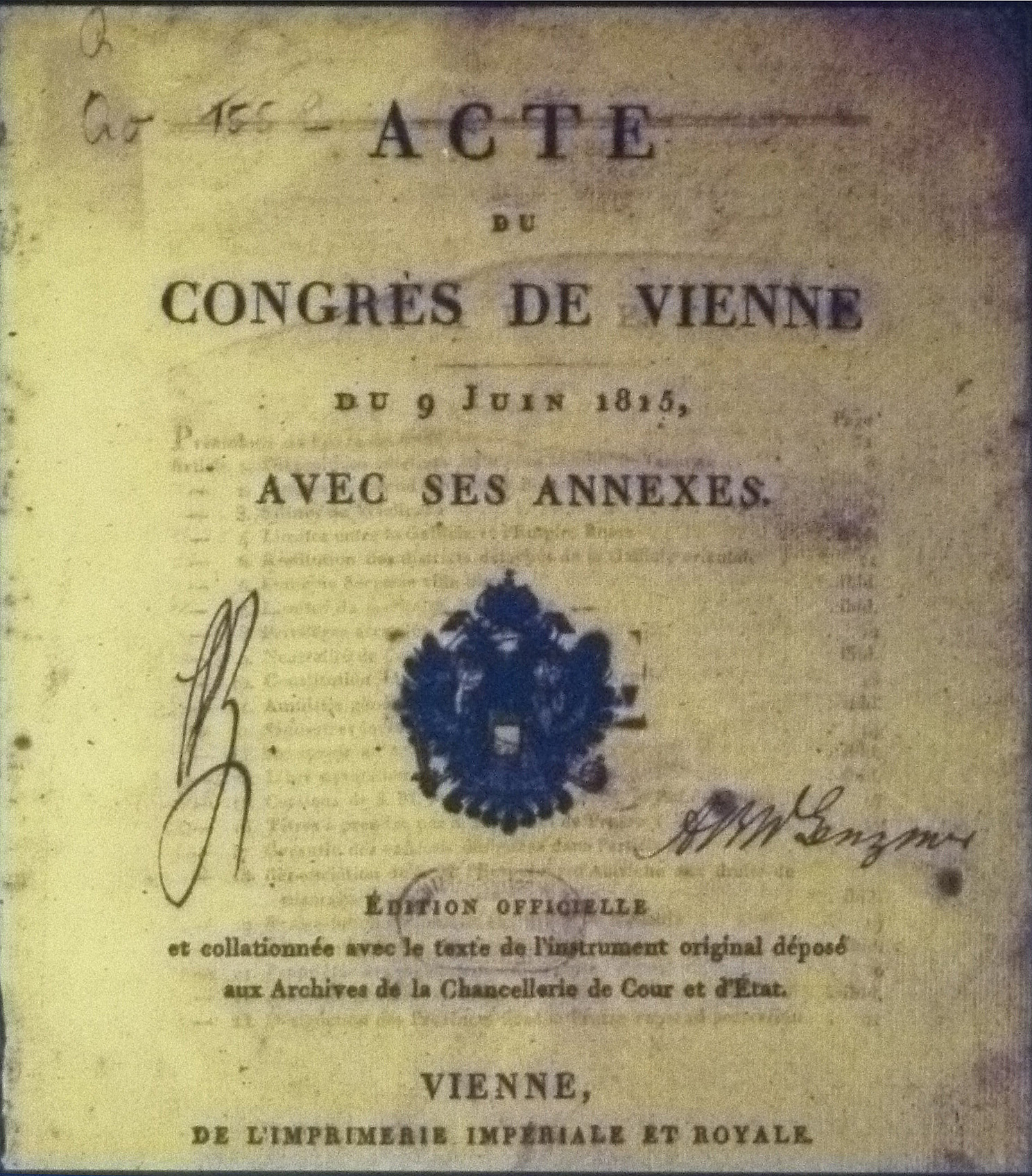

The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties, was signed on 9 June 1815 (nine days before the

The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties, was signed on 9 June 1815 (nine days before the

The Congress's principal results, apart from its confirmation of France's loss of the territories annexed between 1795 and 1810, which had already been settled by the

The Congress's principal results, apart from its confirmation of France's loss of the territories annexed between 1795 and 1810, which had already been settled by the  A large United Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed for the Prince of Orange, including both the old United Provinces and the formerly Austrian-ruled territories in the Southern Netherlands, which gave way to the formation of a democratic state, formally headed by a monarch ('' constitutional monarchy''). Other, less important, territorial adjustments included significant territorial gains for the German Kingdoms of

A large United Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed for the Prince of Orange, including both the old United Provinces and the formerly Austrian-ruled territories in the Southern Netherlands, which gave way to the formation of a democratic state, formally headed by a monarch ('' constitutional monarchy''). Other, less important, territorial adjustments included significant territorial gains for the German Kingdoms of

''Historical dictionary of European imperialism''

, Greenwood Press, p. 149. It was an integral part in what became known as the

''History Volume I: The Ancient World to the Age of Revolution''

, Barron's Educational Series, p. 520. Although the Congress of Vienna preserved the balance of power in Europe, it could not check the spread of revolutionary movements across the continent some 30 years later. Some authors have suggested that the Congress of Vienna may provide a model for settling multiple interlocking conflicts in Eastern Europe that arose after the break-up of the Soviet Union.

online

* Forrest, Alan. "The Hundred Days, the Congress of Vienna and the Atlantic Slave Trade." in ''Napoleon's Hundred Days and the Politics of Legitimacy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018) pp. 163–181. * Gabriëls, Jos. "Cutting the cake: the Congress of Vienna in British, French and German political caricature." ''European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire'' 24.1 (2017): 131–157. illustrated * Gulick, E. V. "The final coalition and the Congress of Vienna, 1813–15" in C. W. Crawley, ed., ''The New Cambridge Modern History, vol 9, 1793–1830'' (1965) pp. 639–67. *

online review

* King, David. ''Vienna, 1814: How the conquerors of Napoleon made love, war, and peace at the congress of Vienna'' (Broadway Books, 2008), popular history * * * Kohler, Max James. "Jewish Rights at the Congresses of Vienna (1814–1815) and Aix-la-Chapelle (1818)" ''Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society,'' No. 26 (1918), pp. 33–12

online

* Kraehe, Enno E. ''Metternich's German Policy. Vol. 2: The Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815'' (1984) * Kwan, Jonathan. "The Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815: diplomacy, political culture and sociability." ''Historical Journal'' 60.4 (2020

online

* Lane, Fernanda Bretones, Guilherme de Paula Costa Santos, and Alain El Youssef. "The Congress of Vienna and the making of second slavery." ''Journal of global slavery'' 4.2 (2019): 162–195. * Langhorne, Richard. "Reflections on the Significance of the Congress of Vienna." ''Review of International Studies'' 12.4 (1986): 313–324. * * Nicolson, Harold. ''The Congress of Vienna: a Study in Allied Unity, 1812–1822'' (1946

online

* ("Chapter II The restoration of Europe") * Peterson, Genevieve. "II. Political inequality at the Congress of Vienna." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 60.4 (1945): 532–554

online

* Schenk, Joep. "National interest versus common interest: The Netherlands and the liberalization of Rhine navigation at the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)." in ''Shaping the International Relations of the Netherlands, 1815–2000'' (Routledge, 2018) pp. 13–31. * * Schroeder, Paul W. ''The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848'' (1996), pp. 517–58

online

* Sluga, Glenda. "'Who Hold the Balance of the World?' Bankers at the Congress of Vienna, and in International History." ''American Historical Review'' 122.5 (2017): 1403–1430. * Vick, Brian. ''The Congress of Vienna. Power and Politics after Napoleon''. Harvard University Press, 2014. . * * ** also published as * *

Animated map Europe and nations, 1815–1914

* Final Act of the Congress of Vienna

Map of Europe in 1815

Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)

Search Results at

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

. Participants were representatives of all European powers and other stakeholders, chaired by Austrian statesman Klemens von Metternich, and held in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

from September 1814 to June 1815.

The objective of the Congress was to provide a long-term peace plan for Europe by settling critical issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Prussia ...

and the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

without the use of (military) violence. The goal was not simply to restore old boundaries, but to resize the main powers so they could balance each other and remain at peace, being at the same time shepherds for the smaller powers. More fundamentally, strongly generalising, conservative thinking leaders like Von Metternich also sought to restrain or eliminate republicanism, liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and revolutional movements which, from their point of view, had upended the constitutional order of the European ancien régime, and which continued to threaten it.

At the negotiation table the position of France was weak in relation to that of Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

, Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-eig ...

, partly due to the military strategy of its dictatorial leader over the last two decades. In the settlement the parties did reach, France had to give up all its recent conquests, while the other three main powers could make major territorial gains. Prussia added territory from smaller states in the west: Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

, 60% of the Kingdom of Saxony and the western part of the former Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

. Austria gained Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 bridges. The isla ...

and much of northern Italy. Russia gained the central and eastern part of the Duchy of Warsaw. Besides that, all agreed upon ratifying the new Kingdom of the Netherlands

, national_anthem = )

, image_map = Kingdom of the Netherlands (orthographic projection).svg

, map_width = 250px

, image_map2 = File:KonDerNed-10-10-10.png

, map_caption2 = Map of the four constituent countries shown to scale

, capital = ...

which had been created just months before from the formerly Austrian territory.

The immediate background was Napoleonic France's defeat and surrender in May 1814, which brought an end to 23 years of nearly continuous war. Negotiations continued despite the outbreak of fighting triggered by Napoleon's return from exile and resumption of power in France during the Hundred Days of March to July 1815. The Congress's agreement was signed nine days before Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

Some historians have criticised the outcomes of the Congress for causing the subsequent suppression of national, democratic and liberal movements coming from civilians and it has been seen as a reactionary settlement for the benefit of traditional monarchs. Others, mostly later, have praised the Congress for saving Europe from large widespread wars over almost a century.

The Congress format

The name "Congress of Vienna" was not meant to suggest a formal

The name "Congress of Vienna" was not meant to suggest a formal plenary session

A plenary session or plenum is a session of a conference which all members of all parties are to attend. Such a session may include a broad range of content, from keynotes to panel discussions, and is not necessarily related to a specific st ...

, but rather the creation of a diplomatic organizational framework bringing together stakeholders of all flocks to enable the expression of opinions, interests and sentiments and facilitate discussion of general issues among them. The Congress format had been architected by Von Metternich, assisted by the brilliant Friedrich von Gentz

Friedrich von Gentz (2 May 1764 – 9 June 1832) was an Austrian diplomat and a writer. With Austrian chancellor Von Metternich he was one of the main forces behind the organisation, management and protocol of the Congress of Vienna.

Early ...

, and the first occasion in history where, on a continental scale, national representatives and other stakeholders came together in one city at the same time to discuss and formulate the conditions and provisions of treaties. Before the Congress of Vienna the common method of diplomacy involved the exchange of notes sent back and forth among the several capitals and separate talks in different places, a cumbersome process that required much in the way of time and transportation. The format set at the Congress of Vienna would serve as inspiration for the 1856 peace conference brokered by France (the Congress of Paris

The Congress of Paris is the name for a series of diplomatic meetings held in 1856 in Paris, France, to negotiate peace between the warring powers in the Crimean War that had started almost three years earlier."Paris, Treaty of (1856)". The New E ...

) that settled the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

. The Congress of Vienna settlement gave birth to the Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

, an international political doctrine that emphasized the maintaining of political boundaries, the balance of powers, and respecting spheres of influence and which guided foreign policy among the nations of Europe until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

To reach amiable consensus among the many different nations holding great interest in the settlement proceedings, informal, face-to-face deliberative sessions were held where opinions and proposed solutions could be inventoried. The policy work on which the Concert of Europe was built on came about through closed-doors dealing among the five Great Powers – Austria, Britain, Russia, Prussia and France. The first four of the five dominant peacemakers held sway simply because they brought to the table "negotiating power" that came of hard-won victory in the Napoleonic Wars; France enjoyed her advantageous position largely through the brilliant diplomatic maneuvering by senior statesman Talleyrand. Lesser powers, like Spain, Sweden, and Portugal, were given few opportunities to advocate their interests and only occasionally partook in the meetings held between the great powers. However, because all representatives were gathered in one city it was relatively easy to communicate, to hear and spread news and gossip, and to present points of view for both powerful and less powerful nations. Also of great importance to the parties convened in Paris were the opportunities presented at wine and dinner functions to establish formal relationships with one another and build-up diplomatic networks.

Preliminaries

The Treaty of Chaumont in 1814 had reaffirmed decisions that had been made already and that would be ratified by the more important Congress of Vienna of 1814–15. They included the establishment of a confederated Germany, the division of Italy into independent states, the restoration of the Bourbon kings of Spain, and the enlargement of the Netherlands to include what in 1830 became modern Belgium. The Treaty of Chaumont became the cornerstone of the European Alliance that formed the balance of power for decades. Other partial settlements had already occurred at theTreaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

between France and the Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

, and the Treaty of Kiel that covered issues raised regarding Scandinavia. The Treaty of Paris had determined that a "general congress" should be held in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

and that invitations would be issued to "all the Powers engaged on either side in the present war". The opening was scheduled for July 1814.

Participants

The four great powers and Bourbon France

Four great powers had previously formed the core of theSixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor six ...

, a covenant of nations allied in the war against France. On the verge of Napoleon's defeat they had outlined their common position in the Treaty of Chaumont (March 1814), and negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1814) with the Bourbons during their restoration:

* Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

was represented by Prince von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

, the Foreign Minister, and by his deputy, Baron Johann von Wessenberg. As the Congress's sessions were in Vienna, Emperor Francis was kept closely informed.

* The United Kingdom was represented first by its Foreign Secretary, Viscount Castlereagh; then by the Duke of Wellington, after Castlereagh's return to England in February 1815. In the last weeks it was headed by the Earl of Clancarty

Earl of Clancarty is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Ireland.

History

The title was created for the first time in 1658 in favour of Donough MacCarty, 2nd Viscount Muskerry, of the MacCarthy of Muskerry dynasty. He had ...

, after Wellington left to face Napoleon during the Hundred Days.

* Tsar Alexander I controlled the Russian delegation which was formally led by the foreign minister, Count Karl Robert Nesselrode. The tsar had two main goals, to gain control of Poland and to promote the peaceful coexistence of European nations. He succeeded in forming the Holy Alliance

The Holy Alliance (german: Heilige Allianz; russian: Священный союз, ''Svyashchennyy soyuz''; also called the Grand Alliance) was a coalition linking the monarchist great powers of Austria, Prussia, and Russia. It was created after ...

(1815), based on monarchism and anti-secularism, and formed to combat any threat of revolution or republicanism.

* Prussia was represented by Prince Karl August von Hardenberg, the Chancellor, and the diplomat and scholar Wilhelm von Humboldt. King Frederick William III of Prussia was also in Vienna, playing his role behind the scenes.

* France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, the "fifth" power, was represented by its foreign minister, Talleyrand, as well as the Minister Plenipotentiary the Duke of Dalberg. Talleyrand had already negotiated the Treaty of Paris (1814) for Louis XVIII of France; the king, however, distrusted him and was also secretly negotiating with Metternich, by mail.

The lesser powers, parties to the Treaty of Paris, 1814

These parties had not been part of the Chaumont agreement, but had joined the Treaty of Paris (1814): * Spain – Pedro Gómez de Labrador, 1st Marquess of Labrador * Portugal – Plenipotentiaries: Pedro de Sousa Holstein, Count of Palmela;António de Saldanha da Gama, Count of Porto Santo

António de Saldanha da Gama, Count of Porto Santo (Lisbon, 5 February 1778 – 1839) was a Portuguese politician, navy officer, diplomat and colonial administrator. He was the Portuguese plenipotentiary at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. While at ...

; Joaquim Lobo da Silveira.

* Sweden – Count Carl Löwenhielm

Count Carl Axel Löwenhielm (3 November 1772 – 9 June 1861) was a Swedish military officer, diplomat, and politician.

He was an illegitimate son of King Charles XIII of Sweden and Augusta von Fersen (married to the Chancellor of the Royal Co ...

Other nations

*Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

– Count Niels Rosenkrantz, foreign minister. King Frederick VI was also present in Vienna.

* Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

– Earl of Clancarty

Earl of Clancarty is a title that has been created twice in the Peerage of Ireland.

History

The title was created for the first time in 1658 in favour of Donough MacCarty, 2nd Viscount Muskerry, of the MacCarthy of Muskerry dynasty. He had ...

, the British Ambassador at the Dutch court, and Baron Hans von Gagern

* Switzerland – Every canton had its own delegation. Charles Pictet de Rochemont from Geneva played a prominent role.

* Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

– Marquis .

* The Papal States – Cardinal Ercole Consalvi

* The Order of St. John of Malta – Fra Antonio Miari, Fra Daniello Berlinghieri and Fra Augusto Viè de Cesarini

* Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

– Marquise Agostino Pareto, Senator of the Republic.

* Grand Duchy of Tuscany – .

* Kingdom of Sicily – Alvaro Ruffo della Scaletta, Luigi de' Medici di Ottajano, Antonio Maresca di Serracapriola and Fabrizio Ruffo di Castelcicala

* On German issues:

** Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

– Maximilian Graf von Montgelas

** Württemberg –

** Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

, then in a personal union with the British crown – Ernst zu Münster

Graf Ernst Friedrich Herbert zu Münster (born 1 March 1766 Osnabrück; died 20 May 1839 Hanover) was a German statesman, politician and minister in the service of the House of Hanover.

Biography

Ernst zu Münster was born the son of Georg zu (1 ...

. (King George III had refused to recognize the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 and maintained a separate diplomatic staff as Elector of Hanover

The Electorate of Hanover (german: Kurfürstentum Hannover or simply ''Kurhannover'') was an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire, located in northwestern Germany and taking its name from the capital city of Hanover. It was formally known as ...

to conduct the affairs of the family estate, the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, until the results of the Congress were concluded establishing the Kingdom of Hanover.)

** Mecklenburg-Schwerin –

Other stakeholders, entertaining side program

Virtually every state in Europe had a delegation in Vienna – more than 200 states and princely houses were represented at the Congress. In addition, there were representatives of cities, corporations, religious organizations (for instance, abbeys) and special interest groups – e.g., a delegation representing German publishers, demanding a copyright law and freedom of the press. With them came a host of courtiers, secretaries, civil servants and ladies to enjoy the magnificent social life of the Austrian court. The Congress was noted for its lavish entertainment: according to a famous joke of an attendee, it danced a lot but didn't move forward. On the other hand, the possibilities for informal gatherings created by this “side program” may have helped ensure the Congress's success.Diplomatic tactics

Talleyrand (France)

Initially, the representatives of the four victorious powers hoped to exclude the French from serious participation in the negotiations, but Talleyrand skillfully managed to insert himself into "her inner councils" in the first weeks of negotiations. He allied himself to a Committee of Eight lesser powers (including Spain, Sweden, and Portugal) to control the negotiations. Once Talleyrand was able to use this committee to make himself a part of the inner negotiations, he then left it, once again abandoning his allies. The major Allies' indecision on how to conduct their affairs without provoking a united protest from the lesser powers led to the calling of a preliminary conference on the protocol, to which Talleyrand and the Marquess of Labrador, Spain's representative, were invited on September 30, 1814. Congress SecretaryFriedrich von Gentz

Friedrich von Gentz (2 May 1764 – 9 June 1832) was an Austrian diplomat and a writer. With Austrian chancellor Von Metternich he was one of the main forces behind the organisation, management and protocol of the Congress of Vienna.

Early ...

reported, "The intervention of Talleyrand and Labrador has hopelessly upset all our plans. Talleyrand protested against the procedure we have adopted and soundly eated us for two hours. It was a scene I shall never forget." The embarrassed representatives of the Allies replied that the document concerning the protocol they had arranged actually meant nothing. "If it means so little, why did you sign it?" snapped Labrador.

Talleyrand's policy, directed as much by national as personal ambitions, demanded the close but by no means amicable relationship he had with Labrador, whom Talleyrand regarded with disdain. Labrador later remarked of Talleyrand: "that cripple, unfortunately, is going to Vienna." Talleyrand skirted additional articles suggested by Labrador: he had no intention of handing over the 12,000 ''afrancesados'' – Spanish fugitives, sympathetic to France, who had sworn fealty to Joseph Bonaparte, nor the bulk of the documents, paintings, pieces of fine art, and books that had been looted from the archives, palaces, churches and cathedrals of Spain.

Polish-Saxon crisis

The most complex topic at the Congress was the Polish-Saxon Crisis. Russia wanted most of Poland, and Prussia wanted all of Saxony, whose king had allied with Napoleon. The tsar would like to become king of Poland. Austria analysed, this could make Russia too powerful, a view which was supported by Britain. The result was a deadlock, for which Talleyrand proposed a solution: admit France to the inner circle, and France would support Austria and Britain. The three nations signed a treaty on 3 January 1815, among only the three of them, agreeing to go to war against Russia and Prussia, if necessary, to prevent the Russo-Prussian plan from coming to fruition.Nicolson, Sir Harold (2001)''The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity: 1812–1822''

Grove Press; Rep. Ed. pp. 140–164. When the Tsar heard of the treaty he agreed to a compromise that satisfied all parties on 24 October 1815. Russia received most of the Napoleonic

Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

as a "Kingdom of Poland" – called Congress Poland, with the tsar as a king ruling it independently of Russia. Russia, however, did not receive the majority of Greater Poland and Kuyavia

Kuyavia ( pl, Kujawy; german: Kujawien; la, Cuiavia), also referred to as Cuyavia, is a historical region in north-central Poland, situated on the left bank of Vistula, as well as east from Noteć River and Lake Gopło. It is divided into three ...

nor the Chełmno Land

Chełmno land ( pl, ziemia chełmińska, or Kulmerland, Old Prussian: ''Kulma'', lt, Kulmo žemė) is a part of the historical region of Pomerelia, located in central-northern Poland.

Chełmno land is named after the city of Chełmno (hist ...

, which were given to Prussia and mostly included within the newly formed Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (german: Großherzogtum Posen; pl, Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the ...

( Poznań), nor Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland until 1596 ...

, which officially became a free city, but in fact was a shared protectorate of Austria, Prussia and Russia. Furthermore, the tsar was unable to unite the new domain with the parts of Poland that had been incorporated into Russia in the 1790s. Prussia received 60 percent of Saxony-later known as the Province of Saxony, with the remainder returned to King Frederick Augustus I as his Kingdom of Saxony.

Subsidies

From the diaries of the master of aiffairs Von Gentz can be learned, diplomatic tactics possibly included bribing. He notes that at the Congress he received £22,000 through Talleyrand from Louis XVIII, while Castlereagh gave him £600, accompanied by "les plus folles promesses"; his diary is full of such entries.Final Agreement

The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties, was signed on 9 June 1815 (nine days before the

The Final Act, embodying all the separate treaties, was signed on 9 June 1815 (nine days before the Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

). Its provisions included:

* Russia received most of the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

(Poland) and retained Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

(which it had annexed from Sweden in 1809 and would hold until 1917, as the Grand Duchy of Finland).

* Prussia received three-fifths of Saxony, western parts of the Duchy of Warsaw (most of which became part of the newly formed Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (german: Großherzogtum Posen; pl, Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the ...

), Gdańsk (Danzig), the Grand Duchy of the Lower Rhine (merger of the former French departments

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (french: département, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level ("territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. Ninety-s ...

of Rhin-et-Moselle, Sarre, and Roer

The Rur or Roer (german: Rur ; Dutch and li, Roer, , ; french: Rour) is a major river that flows through portions of Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. It is a right (eastern) tributary to the Meuse ( nl, links=no, Maas). About 90 perce ...

(Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

The Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg (german: Provinz Jülich-Kleve-Berg) was a province of Prussia from 1815 to 1822. Jülich-Cleves-Berg was established in 1815 from part restored and part newly annexed lands by the Kingdom of Prussia from Franc ...

, itself a merger of the former Prussian Guelders, Principality of Moers, and the Grand Duchy of Berg).

* A German Confederation of 39 states, under the presidency of the Austrian Emperor, formed from the previous 300 states of the Holy Roman Empire. Only portions of the territories of Austria and Prussia were included in the Confederation (roughly the same portions that had been within the Holy Roman Empire).

* The Netherlands and the Southern Netherlands (approximately modern-day Belgium) became a united monarchy, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the House of Orange-Nassau providing the king (the Eight Articles of London).

* To compensate for Orange-Nassau's loss of the Nassau lands to Prussia, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg were to form a personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

under the House of Orange-Nassau, with Luxembourg (but not the Netherlands) inside the German Confederation.

* Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

, given to Denmark in January 1814 in return for the Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, became part of Prussia. France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

received back Guadeloupe from Sweden, with yearly installments payable to the Swedish king.

* The neutrality of the 22 cantons of Switzerland was guaranteed and a federal pact was recommended to them in strong terms. Bienne

, french: Biennois(e)

, neighboring_municipalities= Brügg, Ipsach, Leubringen/Magglingen (''Evilard/Macolin''), Nidau, Orpund, Orvin, Pieterlen, Port, Safnern, Tüscherz-Alfermée, Vauffelin

, twintowns = Iserlohn (Germany)

...

and the Prince-Bishopric of Basel

The Prince-Bishopric of Basel (german: Hochstift Basel, Fürstbistum Basel, Bistum Basel) was an ecclesiastical principality within the Holy Roman Empire, ruled from 1032 by prince-bishops with their seat at Basel, and from 1528 until 1792 at ...

became part of the Canton of Bern. The Congress also suggested a number of compromises for resolving territorial disputes between cantons.

* The former Electorate of Hanover was expanded to a kingdom. It gave up the Duchy of Lauenburg

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg (german: Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg, called ''Niedersachsen'' (Lower Saxony) between the 14th and 17th centuries), was a ''reichsfrei'' duchy that existed from 1296–1803 and again from 1814–1876 in the extreme sou ...

to the Kingdom of Denmark, but gained former territories of the Bishop of Münster and formerly Prussian East Frisia.

* Most of the territorial gains of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

, Württemberg, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, and Nassau under the mediatizations of 1801–1806 were recognized. Bavaria also gained control of the Rhenish Palatinate and of parts of the Napoleonic Duchy of Würzburg and Grand Duchy of Frankfurt. Hesse-Darmstadt, in exchange for giving up the Duchy of Westphalia to Prussia, received Rhenish Hesse

Rhenish Hesse or Rhine HesseDickinson, Robert E (1964). ''Germany: A regional and economic geography'' (2nd ed.). London: Methuen, p. 542. . (german: Rheinhessen) is a region and a former government district () in the German state of Rhineland- ...

with its capital at Mainz.

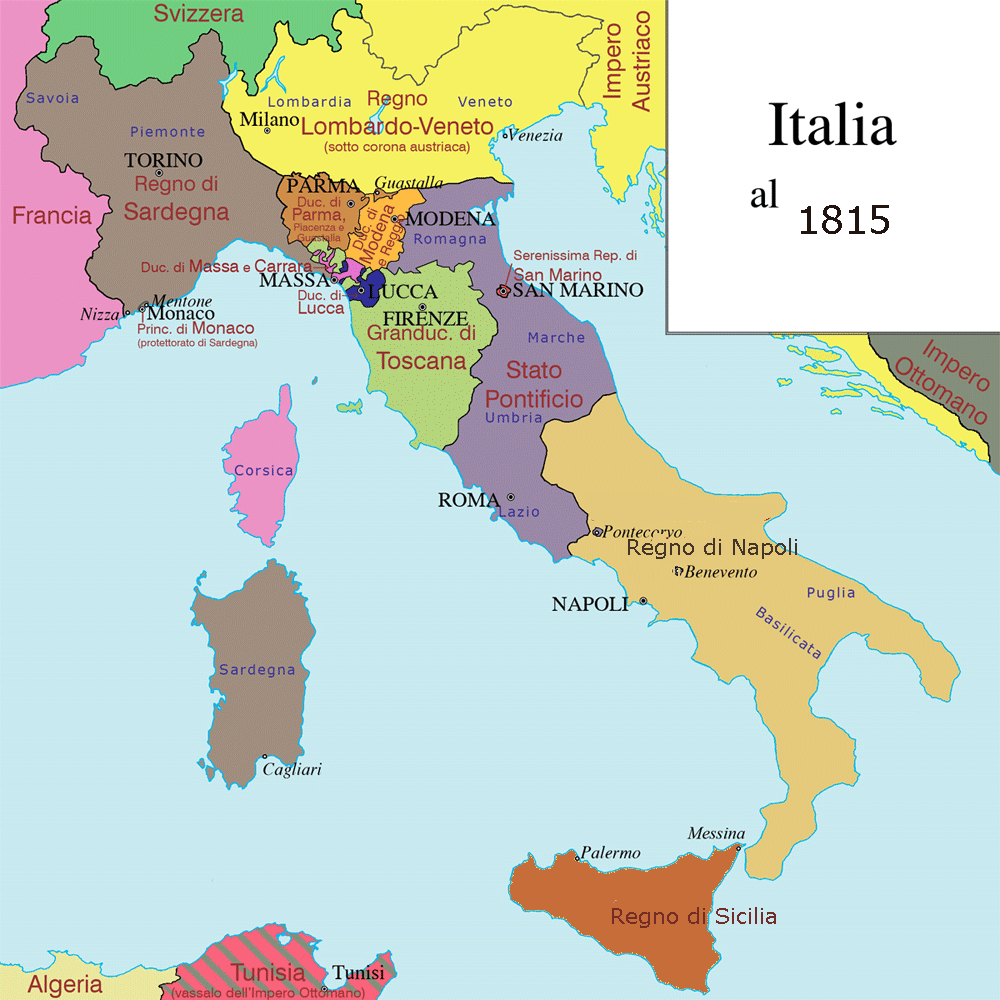

* Austria regained control of the Tyrol and Salzburg; of the former Illyrian Provinces; of Tarnopol district (from Russia); and received Lombardy–Venetia in Italy and Ragusa in Dalmatia. Former Austrian territory in Southwest Germany remained under the control of Württemberg and Baden; the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The pe ...

were also not recovered.

* Ferdinand III was restored as Grand Duke of Tuscany

The rulers of Tuscany varied over time, sometimes being margraves, the rulers of handfuls of border counties and sometimes the heads of the most important family of the region.

Margraves of Tuscany, 812–1197 House of Boniface

:These were origin ...

.

* Archduke Francis IV was acknowledged as the ruler of the Duchy of Modena, Reggio and Mirandola;

* Maria Beatrice d'Este was restored as Duchess of Massa and Princess of Carrara, and the Imperial fiefs in Lunigiana, which were not re-established, were also bestowed upon her.

* The Papal States under the rule of the Pope were restored to their former extent, with the exception of Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin, which remained part of France.

* Britain retained control of the Cape Colony in Southern Africa; Tobago; Ceylon; and various other colonies in Africa and Asia. Other colonies, most notably the Dutch East Indies and Martinique, reverted to their previous overlords.

* The King of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, re-established in Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

, Nice, and Savoy, gained control of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

(putting an end to the brief proclamation of a restored Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the La ...

).

* The Duchies of Parma, Piacenza and Guastalla were taken from the House of Bourbon-Parma

The House of Bourbon-Parma ( it, Casa di Borbone di Parma) is a cadet branch of the Spanish royal family, whose members once ruled as King of Etruria and as Duke of Parma and Piacenza, Guastalla, and Lucca. The House descended from the Fren ...

and given to Marie Louise of Austria for her lifetime.

* The Duchy of Lucca was established temporarily as compensation for the House of Bourbon-Parma, (with reversionary rights to Parma after the death of Marie Louise, which were attributed through a collateral treaty in 1817, also stipulating that the Duchy of Lucca would then in turn be annexed by the Grand Duchy of Tuscany).

* The slave trade was condemned.

* Freedom of navigation was guaranteed for many rivers, notably the Rhine and the Danube.

Representatives of Austria, France, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, Prussia, Russia, Sweden-Norway

Sweden and Norway or Sweden–Norway ( sv, Svensk-norska unionen; no, Den svensk-norske union(en)), officially the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, and known as the United Kingdoms, was a personal union of the separate kingdoms of Sweden ...

, and Britain signed the Final Act. Spain did not sign, but ratified the outcome in 1817.

Subsequently, Ferdinand IV, the Bourbon King of Sicily, regained control of the Kingdom of Naples after Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

, the king installed by Bonaparte, supported Napoleon in the Hundred Days and started the 1815 Neapolitan War by attacking Austria.

Other changes

The Congress's principal results, apart from its confirmation of France's loss of the territories annexed between 1795 and 1810, which had already been settled by the

The Congress's principal results, apart from its confirmation of France's loss of the territories annexed between 1795 and 1810, which had already been settled by the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, were the enlargement of Russia, (which gained most of the Duchy of Warsaw

The Duchy of Warsaw ( pl, Księstwo Warszawskie, french: Duché de Varsovie, german: Herzogtum Warschau), also known as the Grand Duchy of Warsaw and Napoleonic Poland, was a French client state established by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1807, during ...

) and Prussia, which acquired the district of Poznań, Swedish Pomerania, Westphalia and the northern Rhineland. The consolidation of Germany from the nearly 300 states of the Holy Roman Empire (dissolved in 1806) into a much less complex system of thirty-nine states (4 of which were free cities) was confirmed. These states formed a loose German Confederation under the leadership of Austria.

Representatives at the Congress agreed to numerous other territorial changes. By the Treaty of Kiel, Norway had been ceded by the king of Denmark-Norway to the king of Sweden. This sparked the nationalist movement which led to the establishment of the Kingdom of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

on 17 May 1814 and the subsequent personal Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

with Sweden. Austria gained Lombardy–Venetia in Northern Italy, while much of the rest of North-Central Italy went to Habsburg dynasties (the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Modena

A duchy, also called a dukedom, is a medieval country, territory, fief, or domain ruled by a duke or duchess, a ruler hierarchically second to the king or queen in Western European tradition.

There once existed an important difference between ...

, and the Duchy of Parma).

The Papal States were restored to the Pope. The Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was restored to its mainland possessions, and also gained control of the Republic of Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

. In Southern Italy, Napoleon's brother-in-law, Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

, was originally allowed to retain his Kingdom of Naples, but his support of Napoleon in the Hundred Days led to the restoration of the Bourbon Ferdinand IV to the throne.

A large United Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed for the Prince of Orange, including both the old United Provinces and the formerly Austrian-ruled territories in the Southern Netherlands, which gave way to the formation of a democratic state, formally headed by a monarch ('' constitutional monarchy''). Other, less important, territorial adjustments included significant territorial gains for the German Kingdoms of

A large United Kingdom of the Netherlands was formed for the Prince of Orange, including both the old United Provinces and the formerly Austrian-ruled territories in the Southern Netherlands, which gave way to the formation of a democratic state, formally headed by a monarch ('' constitutional monarchy''). Other, less important, territorial adjustments included significant territorial gains for the German Kingdoms of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

(which gained East Frisia from Prussia and various other territories in Northwest Germany) and Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

(which gained the Rhenish Palatinate and territories in Franconia). The Duchy of Lauenburg

The Duchy of Saxe-Lauenburg (german: Herzogtum Sachsen-Lauenburg, called ''Niedersachsen'' (Lower Saxony) between the 14th and 17th centuries), was a ''reichsfrei'' duchy that existed from 1296–1803 and again from 1814–1876 in the extreme sou ...

was transferred from Hanover to Denmark, and Prussia annexed Swedish Pomerania

Swedish Pomerania ( sv, Svenska Pommern; german: Schwedisch-Pommern) was a dominion under the Swedish Crown from 1630 to 1815 on what is now the Baltic coast of Germany and Poland. Following the Polish War and the Thirty Years' War, Sweden held ...

. Switzerland was enlarged, and Swiss neutrality was established. Swiss mercenaries had played a significant role in European wars for several hundred years: the Congress intended to put a stop to these activities permanently.

During the wars, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

had lost its town of Olivenza to Spain and moved to have it restored. Portugal is historically Britain's oldest ally, and with British support succeeded in having the re-incorporation of Olivenza decreed in Article CV of the General Treaty of the Final Act, which stated that "The Powers, recognizing the justice of the claims of ... Portugal and the Brazils, upon the town of Olivenza, and the other territories ceded to Spain by the Treaty of Badajoz of 1801". Portugal ratified the Final Act in 1815 but Spain would not sign, and this became the most important hold-out against the Congress of Vienna. Deciding in the end that it was better to become part of Europe than to stand alone, Spain finally accepted the Treaty on 7 May 1817; however, Olivenza and its surroundings were never returned to Portuguese control and, to the present day, this issue remains unresolved.

The United Kingdom received parts of the West Indies at the expense of the Netherlands and Spain and kept the former Dutch colonies of Ceylon and the Cape Colony as well as Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Heligoland

Heligoland (; german: Helgoland, ; Heligolandic Frisian: , , Mooring Frisian: , da, Helgoland) is a small archipelago in the North Sea. A part of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein since 1890, the islands were historically possessions ...

. Under the Treaty of Paris (1814) Article VIII France ceded to Britain the islands of " Tobago and Saint Lucia, and of the Isle of France and its dependencies, especially Rodrigues and Les Seychelles", and under the Treaty between Great Britain and Austria, Prussia and Russia, respecting the Ionian Islands (signed in Paris on 5 November 1815), as one of the treaties signed during the Peace of Paris (1815), Britain obtained a protectorate over the United States of the Ionian Islands

The United States of the Ionian Islands ( el, Ἡνωμένον Κράτος τῶν Ἰονίων Νήσων, Inoménon-Krátos ton Ioníon Níson, United State of the Ionian Islands; it, Stati Uniti delle Isole Ionie) was a Greek state and a ...

.

Later criticism and praise

The Congress of Vienna has been criticized by 19th century and more recent historians and politicians for ignoring national and liberal impulses, and for imposing a stiflingreaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

* Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and m ...

on the Continent.Olson, James Stuart – Shadle, Robert (1991)''Historical dictionary of European imperialism''

, Greenwood Press, p. 149. It was an integral part in what became known as the

Conservative Order

{{Conservatism sidebar

The Conservative Order was the period in political history of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. From 1815 to 1830, a conscious program by conservative statesmen, including Metternich and Castlereagh, was put into ...

, in which democracy and civil rights associated with the American and French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in coup of 18 Brumaire, November 1799. Many of its ...

s were de-emphasized.

In the 20th century, however, historians and politicians looking backward came to praise the Congress as well, because they saw it did prevent another widespread European war for nearly 100 years (1815–1914) and a significant step in the transition to a new international order in which peace was largely maintained through diplomatic dialogue. Among these is Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

, who in 1954 wrote his doctoral dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

, '' A World Restored'', on it and Paul Schroeder . Historian and jurist Mark Jarrett argues that the diplomatic congress format marked "the true beginning of our modern era". To his analyses the Congress organisation was deliberate conflict management and was the first genuine attempt to create an international order based upon consensus rather than conflict. "Europe was ready," Jarrett states, "to accept an unprecedented degree of international cooperation in response to the French Revolution."Mark Jarrett, ''The Congress of Vienna and Its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon'' (2013) pp. 353, xiv, 187. Historian Paul Schroeder argues that the old formulae for " balance of power" were in fact highly destabilizing and predatory. He says the Congress of Vienna avoided them and instead set up rules that produced a stable and benign equilibrium. The Congress of Vienna was the first of a series of international meetings that came to be known as the Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

, which was an attempt to forge a peaceful balance of power in Europe. It served as a model for later organizations such as the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

in 1919 and the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

in 1945.

Before the opening of the Paris peace conference of 1918, the British Foreign Office commissioned a history of the Congress of Vienna to serve as an example to its own delegates of how to achieve an equally successful peace. Besides, the main decisions of the Congress were made by the Four Great Powers and not all the countries of Europe could extend their rights at the Congress. The Italian peninsula became a mere "geographical expression" as divided into seven parts: Lombardy–Venetia, Modena, Naples–Sicily, Parma, Piedmont–Sardinia, Tuscany, and the Papal States under the control of different powers. Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

remained partitioned between Russia, Prussia and Austria, with the largest part, the newly created Kingdom of Poland

The Kingdom of Poland ( pl, Królestwo Polskie; Latin: ''Regnum Poloniae'') was a state in Central Europe. It may refer to:

Historical political entities

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom existing from 1025 to 1031

* Kingdom of Poland, a kingdom exi ...

, remaining under Russian control.

The arrangements made by the Four Great Powers sought to ensure future disputes would be settled in a manner that would avoid the terrible wars of the previous 20 years.Willner, Mark – Hero, George – Weiner, Jerry Global (2006)''History Volume I: The Ancient World to the Age of Revolution''

, Barron's Educational Series, p. 520. Although the Congress of Vienna preserved the balance of power in Europe, it could not check the spread of revolutionary movements across the continent some 30 years later. Some authors have suggested that the Congress of Vienna may provide a model for settling multiple interlocking conflicts in Eastern Europe that arose after the break-up of the Soviet Union.

See also

* Diplomatic timeline for 1815 * Precedence among European monarchies *Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe was a general consensus among the Great Powers of 19th-century Europe to maintain the European balance of power, political boundaries, and spheres of influence. Never a perfect unity and subject to disputes and jockeying ...

* European balance of power

The European balance of power is the tenet in international relations that no single power should be allowed to achieve hegemony over a substantial part of Europe. During much of the Modern Age, the balance was achieved by having a small number of ...

* Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

* International relations (1814–1919)

* Treaty of Paris (1814)

* Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920)

The Paris Peace Conference was the formal meeting in 1919 and 1920 of the victorious Allies after the end of World War I to set the peace terms for the defeated Central Powers. Dominated by the leaders of Britain, France, the United States and ...

References

Further reading

* * * Ferraro, Guglielmo. ''The Reconstruction of Europe; Talleyrand and the Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815'' (1941online

* Forrest, Alan. "The Hundred Days, the Congress of Vienna and the Atlantic Slave Trade." in ''Napoleon's Hundred Days and the Politics of Legitimacy'' (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2018) pp. 163–181. * Gabriëls, Jos. "Cutting the cake: the Congress of Vienna in British, French and German political caricature." ''European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire'' 24.1 (2017): 131–157. illustrated * Gulick, E. V. "The final coalition and the Congress of Vienna, 1813–15" in C. W. Crawley, ed., ''The New Cambridge Modern History, vol 9, 1793–1830'' (1965) pp. 639–67. *

online review

* King, David. ''Vienna, 1814: How the conquerors of Napoleon made love, war, and peace at the congress of Vienna'' (Broadway Books, 2008), popular history * * * Kohler, Max James. "Jewish Rights at the Congresses of Vienna (1814–1815) and Aix-la-Chapelle (1818)" ''Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society,'' No. 26 (1918), pp. 33–12

online

* Kraehe, Enno E. ''Metternich's German Policy. Vol. 2: The Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815'' (1984) * Kwan, Jonathan. "The Congress of Vienna, 1814–1815: diplomacy, political culture and sociability." ''Historical Journal'' 60.4 (2020

online

* Lane, Fernanda Bretones, Guilherme de Paula Costa Santos, and Alain El Youssef. "The Congress of Vienna and the making of second slavery." ''Journal of global slavery'' 4.2 (2019): 162–195. * Langhorne, Richard. "Reflections on the Significance of the Congress of Vienna." ''Review of International Studies'' 12.4 (1986): 313–324. * * Nicolson, Harold. ''The Congress of Vienna: a Study in Allied Unity, 1812–1822'' (1946

online

* ("Chapter II The restoration of Europe") * Peterson, Genevieve. "II. Political inequality at the Congress of Vienna." ''Political Science Quarterly'' 60.4 (1945): 532–554

online

* Schenk, Joep. "National interest versus common interest: The Netherlands and the liberalization of Rhine navigation at the Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)." in ''Shaping the International Relations of the Netherlands, 1815–2000'' (Routledge, 2018) pp. 13–31. * * Schroeder, Paul W. ''The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848'' (1996), pp. 517–58

online

* Sluga, Glenda. "'Who Hold the Balance of the World?' Bankers at the Congress of Vienna, and in International History." ''American Historical Review'' 122.5 (2017): 1403–1430. * Vick, Brian. ''The Congress of Vienna. Power and Politics after Napoleon''. Harvard University Press, 2014. . * * ** also published as * *

Primary sources

* * * *Other languages

*External links

Animated map Europe and nations, 1815–1914

* Final Act of the Congress of Vienna

Map of Europe in 1815

Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)

Search Results at

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

{{Authority control

Diplomatic conferences in Austria

19th-century diplomatic conferences

Peace treaties

Treaties involving territorial changes

1814 in international relations

1814 in law

1814 in the Austrian Empire

1815 in international relations

1815 in the Austrian Empire

1815 in law

1815 conferences

1815 treaties

1815 in Europe

1815 in Switzerland

19th century in Vienna

Reactionary

European political history

Modern history of Italy

Treaties of the Austrian Empire

Treaties of the Bourbon Restoration

Treaties of the Kingdom of Portugal

Treaties of the Kingdom of Prussia

Treaties of the Russian Empire

Treaties of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway

Treaties of the United Kingdom (1801–1922)

Treaties of the Spanish Empire