Congregation of the Index on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

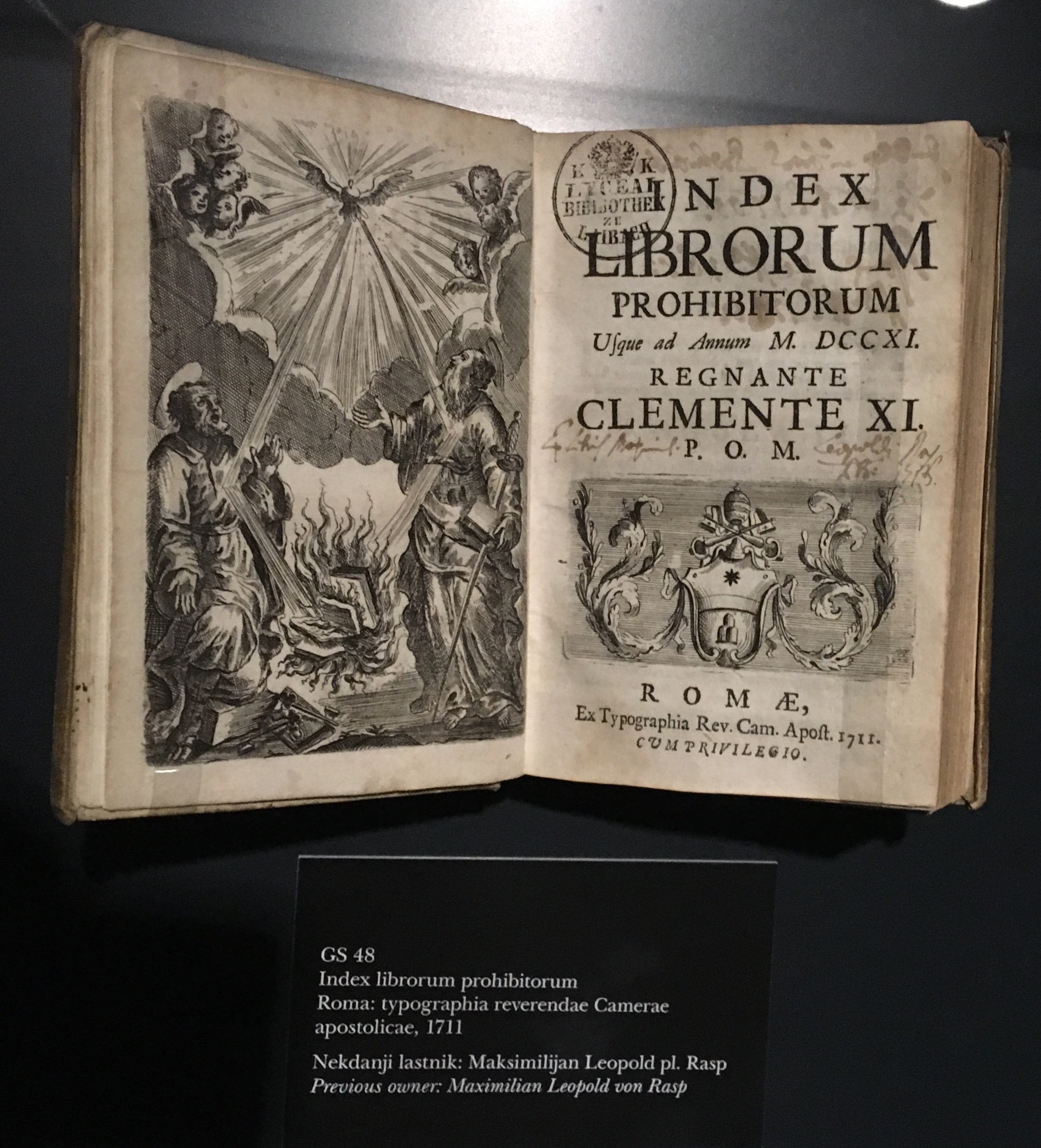

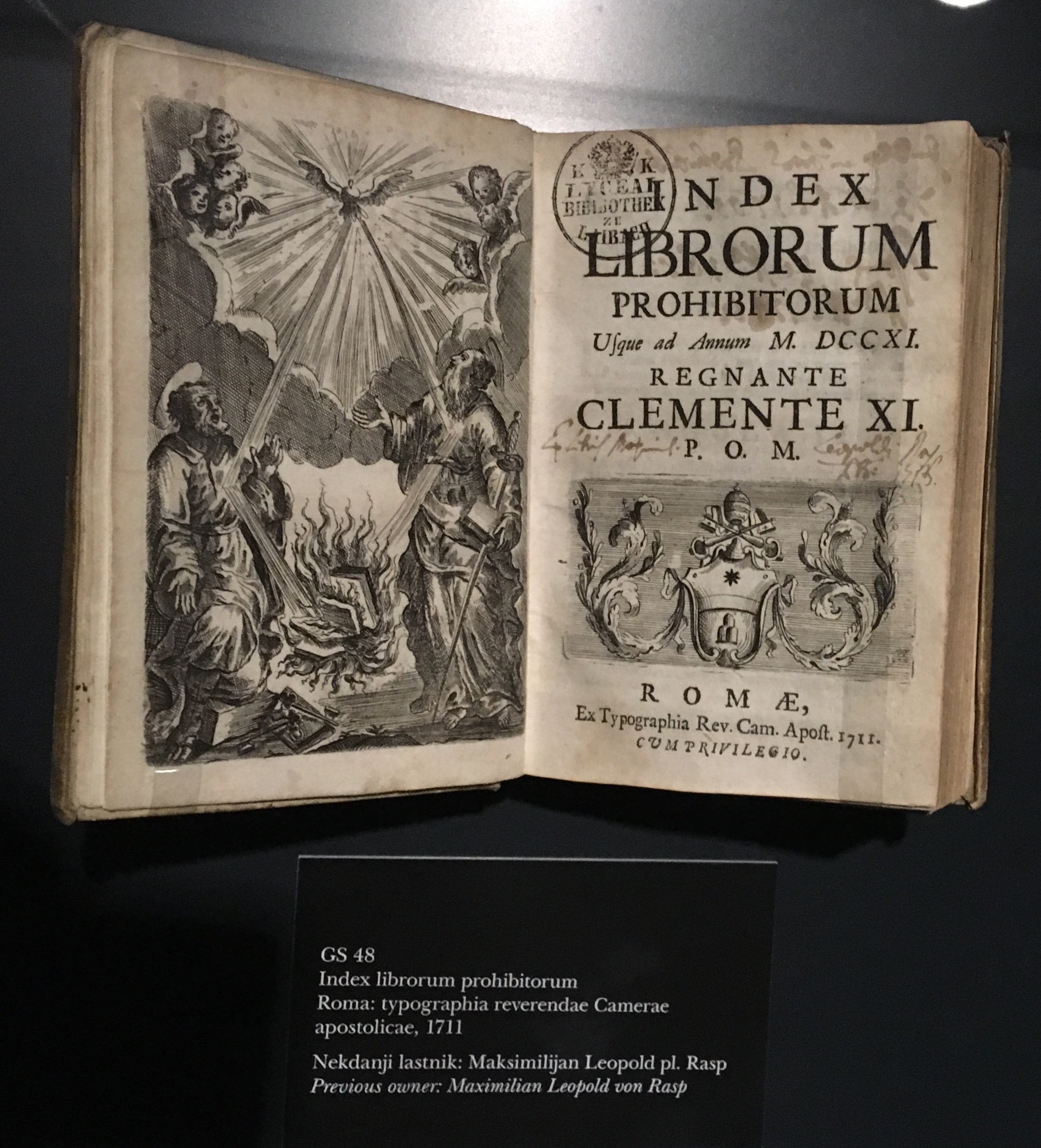

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed

Charles B. Schmitt, ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1988, ) pp. 45–46 There were attempts to ban heretical books before the sixteenth century, notably in the ninth-century ''Decretum Glasianum''; the ''Index of Prohibited Books'' of 1560 banned thousands of book titles and blacklisted publications, including the works of Europe's intellectual elites. The 20th and final edition of the index appeared in 1948, and the ''Index'' was formally abolished on 14 June 1966 by

The historical context in which the ''Index'' appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by

The historical context in which the ''Index'' appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529);

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529);

In 1571, a special

In 1571, a special  This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the ''Index Expurgatorius'', which was cited by Thomas James in 1627 as "an invaluable reference work to be used by the curators of the

This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the ''Index Expurgatorius'', which was cited by Thomas James in 1627 as "an invaluable reference work to be used by the curators of the

(Verso 1976 ), pp. 245–246 and the Church's ''Index'' was not recognized. Spain had its own ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum'', which corresponded largely to the Church's, but also included a list of books that were allowed once the forbidden part (sometimes a single sentence) was removed or "expurgated".

Noteworthy figures on the Index include

Noteworthy figures on the Index include

Facsimile of the 1559 index

"The first Roman ''Index of Prohibited Books'' (''Index librorum prohibitorum''), published in 1559 under Paul IV, was very severe, and was therefore mitigated under that pontiff by decree of the Holy Office of 14 June of the same year. It was only in 1909 that this ''Moderatio Indicis librorum prohibitorum'' (''Mitigation of the Index of Prohibited Books'') was rediscovered in ''Codex Vaticanus lat. 3958, fol. 74'', and was published for the first time."

The ten "tridentine" rules on the censorship of books (English)

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20080307182801/http://news.monstersandcritics.com/europe/features/article_1070798.php/Vatican_opens_up_secrets_of_Index_of_Forbidden_Books Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books, Dec 22, 2005]

Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books

– ''

''An index of prohibited books, by command of the present pope, Gregory XVI in 1835; being the latest specimen of the literary policy of the Church of Rome''

Joseph Mendham, London: Duncan and Malcolm, 1840. Also at th

archive.org

* (History and commentary of the index from 1909) {{Authority control History of the Catholic Church Censorship in Christianity 1559 in law 16th-century Catholicism 16th-century Christian texts Christianity and law in the 16th century Counter-Reformation Vatican Library Book censorship Canon law history Lists of prohibited books Religious controversies in literature 16th-century Latin books

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index

The ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' ("List of Prohibited Books") was a list of publications deemed heresy, heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former Dicastery of the Roman Curia), and Catholics were fo ...

(a former Dicastery

A dicastery (from gr, δικαστήριον, dikastērion, law-court, from Dikastes, δικαστής, 'judge, juror') is the name of some departments of the Roman Curia.

''Pastor bonus''

''Pastor bonus'' (1988), includes this definition:

...

of the Roman Curia), and Catholics

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

were forbidden to read them.Grendler, Paul F. "Printing and censorship" in ''The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy''Charles B. Schmitt, ed. (Cambridge University Press, 1988, ) pp. 45–46 There were attempts to ban heretical books before the sixteenth century, notably in the ninth-century ''Decretum Glasianum''; the ''Index of Prohibited Books'' of 1560 banned thousands of book titles and blacklisted publications, including the works of Europe's intellectual elites. The 20th and final edition of the index appeared in 1948, and the ''Index'' was formally abolished on 14 June 1966 by

Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

.''The Church in the Modern Age'', (Volume 10) by Hubert Jedin, John Dolan, Gabriel Adriányi 1981 , page 168

The ''Index'' condemned religious and secular texts alike, grading works by the degree to which they were seen to be repugnant to the church. The aim of the list was to protect church members from reading theologically, culturally, or politically disruptive books. Such books included works by astronomers

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, g ...

, such as the German Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

's '' Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' (published in three volumes from 1618 to 1621), which was on the Index from 1621 to 1835, works by philosophers, such as the Prussian Immanuel Kant's '' Critique of Pure Reason'' (1781), and editions and translations of the Bible that had not been approved. Editions of the ''Index'' also contained the rules of the Church relating to the reading, selling, and preemptive censorship of books.

The canon law of the Latin Church still recommends that works should be submitted to the judgment of the local ordinary

Ordinary or The Ordinary often refer to:

Music

* ''Ordinary'' (EP) (2015), by South Korean group Beast

* ''Ordinary'' (Every Little Thing album) (2011)

* "Ordinary" (Two Door Cinema Club song) (2016)

* "Ordinary" (Wayne Brady song) (2008)

* ...

if they concern sacred Scripture, theology, canon law, or church history, religion or morals. The local ordinary consults someone whom he considers competent to give a judgment and, if that person gives the '' nihil obstat'' ("nothing forbids"), the local ordinary grants the '' imprimatur'' ("let it be printed"). Members of religious institutes require the '' imprimi potest'' ("it can be printed") of their major superior to publish books on matters of religion or morals.

Some of the scientific theories contained in works in early editions of the ''Index'' have long been taught at Catholic universities. For example, the general prohibition of books advocating heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

was removed from the ''Index'' in 1758, but two Franciscan mathematicians had published an edition of Isaac Newton's '' Principia Mathematica'' (1687) in 1742, with commentaries and a preface stating that the work assumed heliocentrism and could not be explained without it. A work of the Italian Catholic priest and philosopher Antonio Rosmini-Serbati

Blessed Antonio Francesco Davide Ambrogio Rosmini-Serbati (; Rovereto, 25 March 1797Stresa, 1 July 1855) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest and philosopher. He founded the Rosminians, officially the Institute of Charity or , pioneered the ...

was on the ''Index'', but he was beatified

Beatification (from Latin ''beatus'', "blessed" and ''facere'', "to make”) is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a deceased person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in their nam ...

in 2007. Some have argued that the developments since the abolition of the ''Index'' signify "the loss of relevance of the Index in the 21st century."

J. Martínez de Bujanda's ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum, 1600–1966'' lists the authors and writings in the successive editions of the ''Index'', while Miguel Carvalho Abrantes's ''Why Did The Inquisition Ban Certain Books?: A Case Study from Portugal'' tries to understand why certain books were forbidden based on a Portuguese edition of the ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' from 1581.

Background and history

European restrictions on the right to print

The historical context in which the ''Index'' appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by

The historical context in which the ''Index'' appeared involved the early restrictions on printing in Europe. The refinement of moveable type and the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (; – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and Artisan, craftsman who introduced letterpress printing to Europe with his movable type, movable-type printing press. Though not the first of its ki ...

circa 1440 changed the nature of book publishing, and the mechanism by which information could be disseminated to the public. Books, once rare and kept carefully in a small number of libraries, could be mass-produced and widely disseminated.

In the 16th century, both the churches and governments in most European countries attempted to regulate and control printing because it allowed for rapid and widespread circulation of ideas and information. The Protestant Reformation generated large quantities of polemical new writing by and within both the Catholic and Protestant camps, and religious subject-matter was typically the area most subject to control. While governments and church encouraged printing in many ways, which allowed the dissemination of Bibles and government information, works of dissent and criticism could also circulate rapidly. As a consequence, governments established controls over printers across Europe, requiring them to have official licenses to trade and produce books.

The early versions of the ''Index'' began to appear from 1529 to 1571. In the same time frame, in 1557 the English Crown

This list of kings and reigning queens of the Kingdom of England begins with Alfred the Great, who initially ruled Wessex, one of the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms which later made up modern England. Alfred styled himself King of the Anglo-Sax ...

aimed to stem the flow of dissent by chartering the Stationers' Company. The right to print was restricted to two universities and to the 21 existing printers in the city of London, which had between them 53 printing presses.

The French crown also tightly controlled printing, and the printer and writer Etienne Dolet was burned at the stake for atheism in 1546. The 1551 Edict of Châteaubriant

The Edict of Châteaubriant, issued from the seat of Anne, duc de Montmorency in Brittany, was promulgated by Henri II of France, 27 June 1551. The Edict was one of an increasingly severe series of measures taken by Henry II against Protestants, ...

comprehensively summarized censorship positions to date, and included provisions for unpacking and inspecting all books brought into France. The 1557 Edict of Compiègne

The Edict of Compiègne (french: Édit de Compiègne), issued from his Château de Compiègne by Henry II of France, 24 July 1557, applied the death penalty for all convictions of relapsed and obstinate "sacramentarians", for those who went to Gen ...

applied the death penalty to heretics and resulted in the burning of a noblewoman at the stake. Printers were viewed as radical and rebellious, with 800 authors, printers and book dealers being incarcerated in the Bastille. At times, the prohibitions of church and state followed each other, e.g. René Descartes was placed on the Index in the 1660s and the French government prohibited the teaching of Cartesianism in schools in the 1670s.''A companion to Descartes'' by Janet Broughton, John Peter Carriero 2007 page

The Copyright Act 1710 in Britain, and later copyright laws in France, eased this situation. Historian Eckhard Höffner claims that copyright laws and their restrictions acted as a barrier to progress in those countries for over a century, since British publishers could print valuable knowledge in limited quantities for the sake of profit. The German economy prospered in the same time frame since there were no restrictions.

Early indices (1529–1571)

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529);

The first list of the kind was not published in Rome, but in Catholic Netherlands (1529); Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

(1543) and Paris (1551) under the terms of the Edict of Châteaubriant

The Edict of Châteaubriant, issued from the seat of Anne, duc de Montmorency in Brittany, was promulgated by Henri II of France, 27 June 1551. The Edict was one of an increasingly severe series of measures taken by Henry II against Protestants, ...

followed this example. By mid-century, in the tense atmosphere of wars of religion in Germany and France, both Protestant and Catholic authorities reasoned that only control of the press, including a catalog of prohibited works, coordinated by ecclesiastic and governmental authorities could prevent the spread of heresy.Schmitt 1991:45.

Paul F. Grendler (1975) discusses the religious and political climate in Venice from 1540 – 1605. There were many attempts to censor the Venetian press, which was one of the largest concentrations of printers at that time. Both church and government held to a belief in censorship, but the publishers continually pushed back on the efforts to ban books and shut down printing. More than once the index of banned books in Venice was suppressed or suspended because various people took a stand against it.

The first Roman ''Index'' was printed in 1557 under the direction of Pope Paul IV (1555–1559), but then withdrawn for unclear reasons. In 1559, a new index was finally published, banning the entire works of some 550 authors in addition to the individual proscribed titles: "The Pauline Index felt that the religious convictions of an author contaminated all his writing." The work of the censors was considered too severe and met with much opposition even in Catholic intellectual circles; after the Council of Trent had authorised a revised list prepared under Pope Pius IV

Pope Pius IV ( it, Pio IV; 31 March 1499 – 9 December 1565), born Giovanni Angelo Medici, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 25 December 1559 to his death in December 1565. Born in Milan, his family considered ...

, the so-called ''Tridentine Index'' was promulgated in 1564; it remained the basis of all later lists until Pope Leo XIII, in 1897, published his ''Index Leonianus''.

The blacklisting

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

of some Protestant scholars even when writing on subjects a modern reader would consider outside the realm of dogma meant that, unless they obtained a dispensation, obedient Catholic thinkers were denied access to works including: botanist Conrad Gesner's ''Historiae animalium

''Historia animalium'' ("History of the Animals"), published at Zurich in 1551–1558 and 1587, is an encyclopedic "inventory of renaissance zoology" by Conrad Gessner (1516–1565). Gessner was a medical doctor and professor at the Carolinum i ...

''; the botanical works of Otto Brunfels; those of the medical scholar Janus Cornarius; to Christoph Hegendorff

Christoph Hegendorff (1500 – 8 August 1540), of Leipzig, was a Protestant theological scholar and expert of law, an educator, a Protestant reformer and a great, public admirer of Erasmus, whom he called ''optimarum literarum princeps'' ("the pri ...

or Johann Oldendorp

Johann Oldendorp (c. 1486Harold J. Berman''Faith and order'' Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1993, p. 164. – 3 June 1567) was a German jurist and reformer.

Oldendorp was born in Hamburg. He was the son of a merchant and the nephew (on his mother's s ...

on the theory of law; Protestant geographers and cosmographers like Jacob Ziegler

The humanist and theologian Jacob Ziegler (c. 1470/71 — August 1549) of Landau in Bavaria, was an itinerant scholar of geography and cartographer, who lived a wandering life in Europe. He studied at the University of Ingolstadt, then spent some ...

or Sebastian Münster; as well as anything by Protestant theologians like Martin Luther, John Calvin

John Calvin (; frm, Jehan Cauvin; french: link=no, Jean Calvin ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French theologian, pastor and reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system ...

or Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

. Among the inclusions was the Libri Carolini, a theological work from the 9th century court of Charlemagne, which was published in 1549 by Bishop Jean du Tillet and which had already been on two other lists of prohibited books before being inserted into the Tridentine Index.

Sacred Congregation of the Index (1571–1917)

In 1571, a special

In 1571, a special congregation

A congregation is a large gathering of people, often for the purpose of worship.

Congregation may also refer to:

*Church (congregation), a Christian organization meeting in a particular place for worship

*Congregation (Roman Curia), an administra ...

was created, the Sacred Congregation of the Index, which had the specific task to investigate those writings that were denounced in Rome as being not exempt of errors, to update the list of Pope Pius IV regularly and also to make lists of required corrections in case a writing was not to be condemned absolutely but only in need of correction; it was then listed with a mitigating clause (e.g., ''donec corrigatur'' (forbidden until corrected) or ''donec expurgetur'' (forbidden until purged)).

Several times a year, the congregation held meetings. During the meetings, they reviewed various works and documented those discussions. In between the meetings was when the works to be discussed were thoroughly examined, and each work was scrutinized by two people. At the meetings, they collectively decided whether or not the works should be included in the Index. Ultimately, the pope was the one who had to approve of works being added or removed from the Index. It was the documentation from the meetings of the congregation that aided the pope in making his decision.

This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the ''Index Expurgatorius'', which was cited by Thomas James in 1627 as "an invaluable reference work to be used by the curators of the

This sometimes resulted in very long lists of corrections, published in the ''Index Expurgatorius'', which was cited by Thomas James in 1627 as "an invaluable reference work to be used by the curators of the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

when listing those works particularly worthy of collecting". Prohibitions made by other congregations (mostly the Holy Office) were simply passed on to the Congregation of the Index, where the final decrees were drafted and made public, after approval of the Pope (who always had the possibility to condemn an author personally—there are only a few examples of such condemnation, including those of Lamennais and Hermes).

An update to the Index was made by Pope Leo XIII, in the 1897 apostolic constitution Officiorum ac Munerum Officiorum ac Munerum was an Apostolic Constitution issued by Pope Leo XIII on 25 January 1897. It was a major revision of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, a list of books prohibited by the Catholic Church. Along with the 18th century ''Sollicita ...

, known as the "Index Leonianus". Subsequent editions of the Index were more sophisticated; they graded authors according to their supposed degree of toxicity, and they marked specific passages for expurgation rather than condemning entire books.

The Sacred Congregation of the Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

of the Roman Catholic Church later became the Holy Office, and since 1965 has been called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. The Congregation of the Index was merged with the Holy Office in 1917, by the Motu Proprio "Alloquentes Proxime" of Pope Benedict XV; the rules on the reading of books were again reelaborated in the new ''Codex Iuris Canonici''. From 1917 onward, the Holy Office (again) took care of the Index.

Holy Office (1917–1966)

While individual books continued to be forbidden, the last edition of the Index to be published appeared in 1948. This 20th edition contained 4,000 titles censored for various reasons: heresy, moral deficiency, sexual explicitness, and so on. That someatheist

Atheism, in the broadest sense, is an absence of belief in the existence of deities. Less broadly, atheism is a rejection of the belief that any deities exist. In an even narrower sense, atheism is specifically the position that there no ...

s, such as Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, were not included was due to the general ( Tridentine) rule that heretical works (''i.e.'', works that contradict Catholic dogma) are ipso facto forbidden. Some important works are absent simply because nobody bothered to denounce them. Many actions of the congregations were of a definite political content. Among the significant listed works of the period was the Nazi philosopher Alfred Rosenberg's ''Myth of the Twentieth Century

''The Myth of the Twentieth Century'' (german: Der Mythus des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts) is a 1930 book by Alfred Rosenberg, one of the principal ideologues of the Nazi Party and editor of the Nazi paper ''Völkischer Beobachter''. The titular " ...

'' for scorning and rejecting "all dogmas of the Catholic Church, indeed the very fundamentals of the Christian religion".

Abolition (1966)

On 7 December 1965, Pope Paul VI issued the Motu Proprio ''Integrae servandae

Pope Paul VI's reform of the Roman Curia was accomplished through a series of decrees beginning in 1964, principally through the apostolic constitution ''Regimini Ecclesiae universae'' issued on 15 August 1967.

On 28 October 1965, the bishops at ...

'' that reorganized the Holy Office as the ''Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith''. The Index was not listed as being a part of the newly constituted congregation's competence, leading to questioning whether it still was. This question was put to Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, pro-prefect of the congregation, who responded in the negative. The Cardinal also indicated in his response that there was going to be a change in the Index soon.

A June 1966 Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith notification announced that, while the ''Index'' maintained its moral force, in that it taught Christians to beware, as required by the natural law itself, of those writings that could endanger faith and morality, it no longer had the force of ecclesiastical positive law

The canon law of the Catholic Church ("canon law" comes from Latin ') is "how the Church organizes and governs herself". It is the system of laws and ecclesiastical legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Cathol ...

with the associated penalties.

Scope and impact

Censorship and enforcement

The ''Index'' was not simply a reactive work. Roman Catholic authors had the opportunity to defend their writings and could prepare a new edition with necessary corrections or deletions, either to avoid or to limit aban

Ban, or BAN, may refer to:

Law

* Ban (law), a decree that prohibits something, sometimes a form of censorship, being denied from entering or using the place/item

** Imperial ban (''Reichsacht''), a form of outlawry in the medieval Holy Roman ...

. Pre-publication censorship was encouraged.

The ''Index'' was enforceable within the Papal States, but elsewhere only if adopted by the civil powers, as happened in several Italian states. Other areas adopted their own lists of forbidden books. In the Holy Roman Empire book censorship, which preceded publication of the ''Index'', came under control of the Jesuits at the end of the 16th century, but had little effect, since the German princes within the empire set up their own systems. In France it was French officials who decided what books were bannedLucien Febvre, Henri Jean Martin, ''The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450–1800''(Verso 1976 ), pp. 245–246 and the Church's ''Index'' was not recognized. Spain had its own ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum et Expurgatorum'', which corresponded largely to the Church's, but also included a list of books that were allowed once the forbidden part (sometimes a single sentence) was removed or "expurgated".

Continued moral obligation

On 14 June 1966, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith responded to inquiries it had received regarding the continued moral obligation concerning books that had been listed in the Index. The response spoke of the books as examples of books dangerous to faith and morals, all of which, not just those once included in the Index, should be avoided regardless of the absence of any written law against them. The Index, it said, retains its moral force "inasmuch as" (''quatenus'') it teaches the conscience of Christians to beware, as required by the natural law itself, of writings that can endanger faith and morals, but it (the Index of Forbidden Books) no longer has the force of ecclesiastical law with the associated censures. The congregation thus placed on the conscience of the individual Christian the responsibility to avoid all writings dangerous to faith and morals, while at the same time abolishing the previously existing ecclesiastical law and the relative censures, without thereby declaring that the books that had once been listed in the various editions of the Index of Prohibited Books had become free of error and danger. In a letter of 31 January 1985 to Cardinal Giuseppe Siri, regarding the book ''The Poem of the Man-God

''The Poem of the Man-God'' (Italian title: ''Il Poema dell'Uomo-Dio'') is a multi-volume book of about five thousand pages on the life of Jesus Christ written by Maria Valtorta. The current editions of the book bear the title ''The Gospel as Reve ...

'', Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (then Prefect of the Congregation, who later became Pope Benedict XVI), referred to the 1966 notification of the Congregation as follows: "After the dissolution of the Index, when some people thought the printing and distribution of the work was permitted, people were reminded again in ''L'Osservatore Romano'' (15 June 1966) that, as was published in the ''Acta Apostolicae Sedis'' (1966), the Index retains its moral force despite its dissolution. A decision against distributing and recommending a work, which has not been condemned lightly, may be reversed, but only after profound changes that neutralize the harm which such a publication could bring forth among the ordinary faithful."

Changing judgments

The content of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum saw deletions as well as additions over the centuries. Writings byAntonio Rosmini-Serbati

Blessed Antonio Francesco Davide Ambrogio Rosmini-Serbati (; Rovereto, 25 March 1797Stresa, 1 July 1855) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest and philosopher. He founded the Rosminians, officially the Institute of Charity or , pioneered the ...

were placed on the Index in 1849 but were removed by 1855, and Pope John Paul II mentioned Rosmini's work as a significant example of "a process of philosophical enquiry which was enriched by engaging the data of faith". The 1758 edition of the Index removed the general prohibition of works advocating heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

as a fact rather than a hypothesis.

Listed works and authors

Noteworthy figures on the Index include

Noteworthy figures on the Index include Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, and even th ...

, Nicolas Malebranche

Nicolas Malebranche ( , ; 6 August 1638 – 13 October 1715) was a French Oratorian Catholic priest and rationalist philosopher. In his works, he sought to synthesize the thought of St. Augustine and Descartes, in order to demonstrate the ...

, Jean-Paul Sartre, Michel de Montaigne

Michel Eyquem, Sieur de Montaigne ( ; ; 28 February 1533 – 13 September 1592), also known as the Lord of Montaigne, was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance. He is known for popularizing the essay as a liter ...

, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, André Gide, Nikos Kazantzakis, Emanuel Swedenborg, Baruch Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

, Desiderius Erasmus, Immanuel Kant, David Hume, René Descartes, Francis Bacon, Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (; 19 October 160519 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. His writings display a deep curi ...

, John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem '' Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and political ...

, John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

, Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal ( , , ; ; 19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic Church, Catholic writer.

He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. Pa ...

, and Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 – 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delft ...

. The first woman to be placed on the list was Magdalena Haymairus in 1569, who was listed for her children's book ''Die sontegliche Episteln über das gantze Jar in gesangsweis gestellt'' (''Sunday Epistles on the whole Year, put into hymns''). Other women include Anne Askew, Olympia Fulvia Morata

Olimpia Fulvia Morata (1526 – 26 October 1555) was an Italian classical scholar.

Biography

She was born in Ferrara to Fulvio Pellegrino Morato and a certain Lucrezia (possibly Gozi).

Her father, who had been tutor to the young princes of the ...

, Ursula of Munsterberg

Ursula of Munsterberg (german: Ursula von Münsterberg; cs, Uršula z Minstrberka, Voršila Minstrberská, kněžna a Kladská hraběnka; c. 1491/95 or 1499,Cf. Siegismund Justus Ehrhardt: ''Abhandlung vom verderbten Religions-Zustand in Schlesien ...

(1491–1534), Veronica Franco

Veronica Franco (1546–1591) was an Italian poet and courtesan in 16th-century Venice. She is known for her notable clientele, feminist advocacy, literary contributions, and philanthropy. Her humanist education and cultural contributions influe ...

, and Paola Antonia Negri

Paola Antonia Negri, later known as Virginia Negri (1508, Castellanza - 4 April 1555, Milan) was an Italian nun of the Angelic Sisters of St. Paul, of which she was co-founder. She played a dominant role in her community until she was ousted from i ...

(1508–1555).

Contrary to a popular misconception, Charles Darwin's works were never included.

In many cases, an author's ''opera omnia'' (complete works) were forbidden. However, the Index stated that the prohibition of someone's ''opera omnia'' did not preclude works that were not concerned with religion and were not forbidden by the general rules of the Index. This explanation was omitted in the 1929 edition, which was officially interpreted in 1940 as meaning that ''opera omnia'' covered all the author's works without exception.

Cardinal Ottaviani stated in April 1966 that there was too much contemporary literature and the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith could not keep up with it.'' L'Osservatore della Domenica, 24 April 1966, p. 10.

See also

* List of authors and works on the ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum'' * Archive of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith * Book censorship * Clericalism * Nazi book burnings, some of the books mentioned in the list were burned by the NSDAP *Index of Repudiated Books

The . - In the Slavic written tradition, a list (bibliography) of works forbidden to be read by the Christian Church. The works included in this list are renounced (rejected, stripped of authority, obsolete. renounced , and forbidden), apocrypha ...

Notes

References

External links

*Facsimile of the 1559 index

"The first Roman ''Index of Prohibited Books'' (''Index librorum prohibitorum''), published in 1559 under Paul IV, was very severe, and was therefore mitigated under that pontiff by decree of the Holy Office of 14 June of the same year. It was only in 1909 that this ''Moderatio Indicis librorum prohibitorum'' (''Mitigation of the Index of Prohibited Books'') was rediscovered in ''Codex Vaticanus lat. 3958, fol. 74'', and was published for the first time."

The ten "tridentine" rules on the censorship of books (English)

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20080307182801/http://news.monstersandcritics.com/europe/features/article_1070798.php/Vatican_opens_up_secrets_of_Index_of_Forbidden_Books Vatican opens up secrets of Index of Forbidden Books, Dec 22, 2005]

Secrets Behind The Forbidden Books

– ''

America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

'', 7 February 2005''An index of prohibited books, by command of the present pope, Gregory XVI in 1835; being the latest specimen of the literary policy of the Church of Rome''

Joseph Mendham, London: Duncan and Malcolm, 1840. Also at th

archive.org

* (History and commentary of the index from 1909) {{Authority control History of the Catholic Church Censorship in Christianity 1559 in law 16th-century Catholicism 16th-century Christian texts Christianity and law in the 16th century Counter-Reformation Vatican Library Book censorship Canon law history Lists of prohibited books Religious controversies in literature 16th-century Latin books