Committee of Both Kingdoms on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Committee of Both Kingdoms, (known as the Derby House Committee from late 1647), was a committee set up during the

The seven members appointed from among the House of Lords were:

* Algernon, Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), one of the "peace lords", in 1642 he was dismissed as Lord High Admiral and in 1643 headed the parliamentary delegation to negotiate with the king at Oxford.

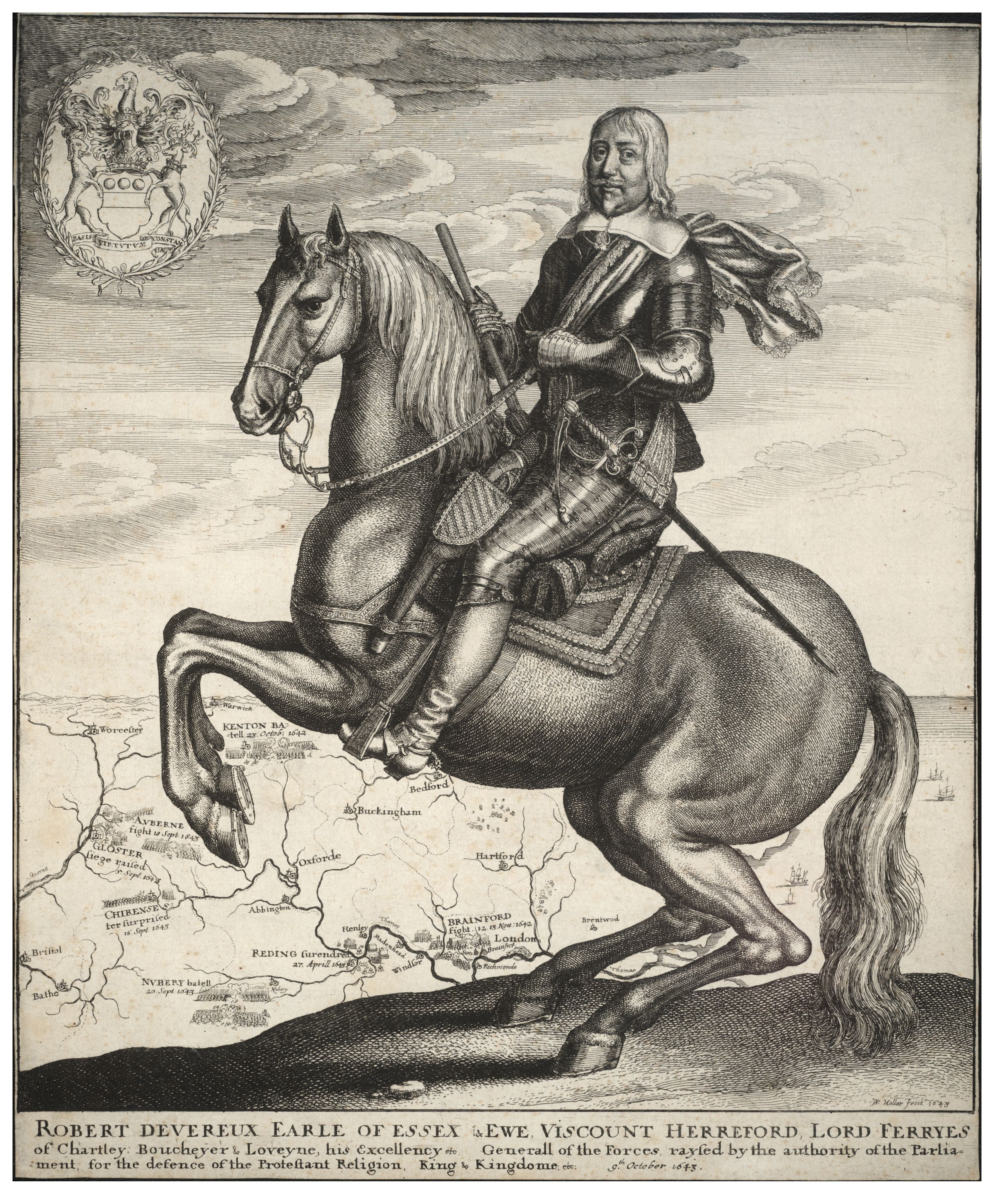

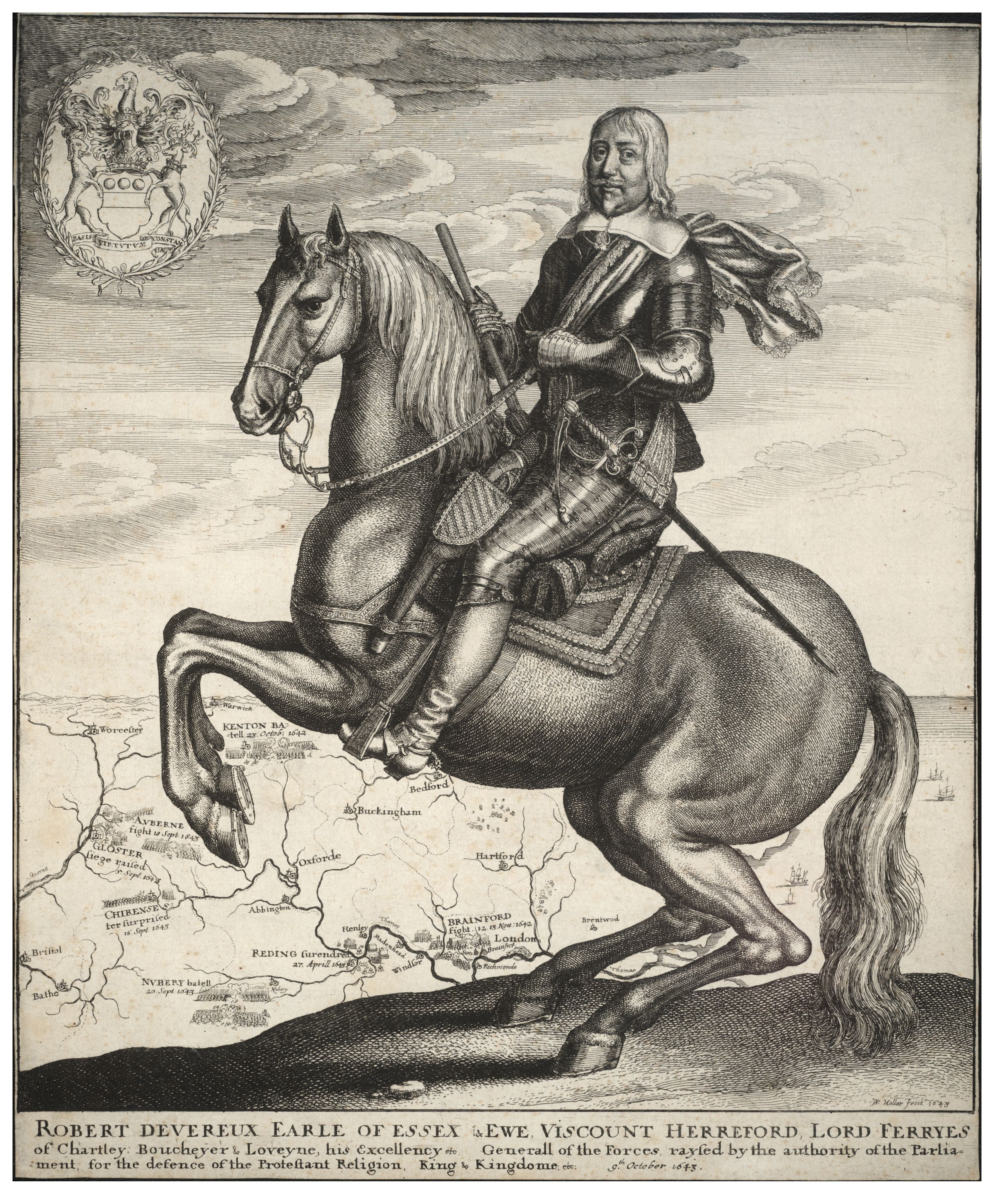

* Robert, Earl of Essex (1591–1646), in 1642 became the first Captain-General of the Parliamentary army, but was overshadowed by the ascendancy of Oliver Cromwell and resigned in 1646, dying later the same year.

* Robert, Earl of Warwick (1587–1658), from 1642 Lord High Admiral, appointed by Parliament. In 1648, he captured the Castles of Walmer, Deal, and Sandown for Parliament.

* Edward, Earl of Manchester (1602–1671), in August 1643 was appointed major-general of the parliamentary forces in the east, with Cromwell as his deputy; he was in command at

The seven members appointed from among the House of Lords were:

* Algernon, Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), one of the "peace lords", in 1642 he was dismissed as Lord High Admiral and in 1643 headed the parliamentary delegation to negotiate with the king at Oxford.

* Robert, Earl of Essex (1591–1646), in 1642 became the first Captain-General of the Parliamentary army, but was overshadowed by the ascendancy of Oliver Cromwell and resigned in 1646, dying later the same year.

* Robert, Earl of Warwick (1587–1658), from 1642 Lord High Admiral, appointed by Parliament. In 1648, he captured the Castles of Walmer, Deal, and Sandown for Parliament.

* Edward, Earl of Manchester (1602–1671), in August 1643 was appointed major-general of the parliamentary forces in the east, with Cromwell as his deputy; he was in command at

On 27 April 1646, Charles left Oxford and surrendered to the

On 27 April 1646, Charles left Oxford and surrendered to the

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities united in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bi ...

by the Parliamentarian faction in association with representatives from the Scottish Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

s, after they made an alliance (the Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August 1 ...

) in late 1643.

When the Scottish army entered England by invitation of the English Parliament in January 1644 the Parliamentary Committee of Safety was replaced by an ad hoc committee representative of both kingdoms which, by parliamentary ordinance of 16 February, was formally constituted as the Committee of Both Kingdoms. The English contingent consisted of seven peers and 14 commoners. Its object was the management of peace overtures to, or making war on, the King. It was conveniently known as the Derby House Committee from 1647, when the Scots withdrew. Its influence long reduced by the growth of the army's, it was dissolved by Parliament on 7 February 1649 (soon after the execution of Charles I

The execution of Charles I by beheading occurred on Tuesday, 30 January 1649 outside the Banqueting House on Whitehall. The execution was the culmination of political and military conflicts between the royalists and the parliamentarians in E ...

on 30 January) and replaced by the Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.

A sub-committee on Irish affairs met from 1646 to 1648. The sub-committee spent, in Ireland, money raised by the Committee of Both Houses.

Creation

On 9 January 1644 theEstates of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council of ...

sitting in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

arranged for a special commission to go to London with full powers to represent the Scottish Estates.Dates are in the Julian Calendar with the start of year on 1 January (see Old Style and New Style dates

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

) The special commission had four members:

*Earl of Loudoun

Earl of Loudoun (pronounced "loud-on" ), named after Loudoun in Ayrshire, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland. It was created in 1633 for John Campbell, 2nd Lord Campbell of Loudoun, along with the subsidiary title Lord Tarrinzean and Mauchlin ...

— High Chancellor of Scotland

* Lord Maitland—already in London as Scottish Commissioner to the Westminster Assembly

The Westminster Assembly of Divines was a council of divines (theologians) and members of the English Parliament appointed from 1643 to 1653 to restructure the Church of England. Several Scots also attended, and the Assembly's work was adopt ...

* Lord Warriston—due in London as a Commissioner to the Westminster Assembly

*Robert Barclay

Robert Barclay (23 December 16483 October 1690) was a Scottish Quaker, one of the most eminent writers belonging to the Religious Society of Friends and a member of the Clan Barclay. He was a son of Col. David Barclay, Laird of Urie, and his ...

—Provost of Irvine in Ayrshire.

The four Scottish commissioners presented their commission from Scottish Estates to the English Parliament on 5 February. On 16 February, so that the two kingdoms should be "joined in their counsels as well as in their forces", the English Parliament passed an ordinance (''Ordinance concerning the Committee of both Kingdoms'') to form a joint "Committee of the Two Kingdoms" to sit with the four Scottish Commissioners. The ordinance named seven members from the House of Lords and fourteen from the House of Commons to sit on the committee and ordained that six were to be a quorum, always in the proportion of one Lord to two Commoners, and of the Scottish Commissioners meeting with them two were to be a quorum.

The seven members appointed from among the House of Lords were:

* Algernon, Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), one of the "peace lords", in 1642 he was dismissed as Lord High Admiral and in 1643 headed the parliamentary delegation to negotiate with the king at Oxford.

* Robert, Earl of Essex (1591–1646), in 1642 became the first Captain-General of the Parliamentary army, but was overshadowed by the ascendancy of Oliver Cromwell and resigned in 1646, dying later the same year.

* Robert, Earl of Warwick (1587–1658), from 1642 Lord High Admiral, appointed by Parliament. In 1648, he captured the Castles of Walmer, Deal, and Sandown for Parliament.

* Edward, Earl of Manchester (1602–1671), in August 1643 was appointed major-general of the parliamentary forces in the east, with Cromwell as his deputy; he was in command at

The seven members appointed from among the House of Lords were:

* Algernon, Earl of Northumberland (1602–1668), one of the "peace lords", in 1642 he was dismissed as Lord High Admiral and in 1643 headed the parliamentary delegation to negotiate with the king at Oxford.

* Robert, Earl of Essex (1591–1646), in 1642 became the first Captain-General of the Parliamentary army, but was overshadowed by the ascendancy of Oliver Cromwell and resigned in 1646, dying later the same year.

* Robert, Earl of Warwick (1587–1658), from 1642 Lord High Admiral, appointed by Parliament. In 1648, he captured the Castles of Walmer, Deal, and Sandown for Parliament.

* Edward, Earl of Manchester (1602–1671), in August 1643 was appointed major-general of the parliamentary forces in the east, with Cromwell as his deputy; he was in command at Marston Moor

The Battle of Marston Moor was fought on 2 July 1644, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of 1639 – 1653. The combined forces of the English Parliamentarians under Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester and the Scottish Covenanters und ...

, but later fell out with Cromwell, and in November 1644 opposed continuing the war.

* William, Viscount Saye and Sele (1582–1662), was mainly responsible for passing the Self-denying Ordinance

The Self-denying Ordinance was passed by the English Parliament on 3 April 1645. All members of the House of Commons or Lords who were also officers in the Parliamentary army or navy were required to resign one or the other, within 40 days fr ...

through the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminst ...

; and by 1648 wanted a negotiated settlement with the king; he retired into private life after Charles's execution.

* Philip, Lord Wharton (1613–1696), a Puritan and a favourite of Oliver Cromwell, was one of the youngest members of the Committee.

* John, Lord Roberts (1606–1685), with the Self-denying Ordinance of April 1645 he lost his command in Plymouth and was sidelined. Shocked by the execution of the king, he withdrew from public life, but after the Restoration he became Lord Privy Seal

The Lord Privy Seal (or, more formally, the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal) is the fifth of the Great Officers of State in the United Kingdom, ranking beneath the Lord President of the Council and above the Lord Great Chamberlain. Originally, ...

and later Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the King ...

.

The fourteen members appointed from the House of Commons were:

* William Pierrepoint (''c.'' 1607–1678), a Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Great Wenlock, represented parliament in negotiations with the king at Oxford in 1643 and at Uxbridge in 1645

* Henry Vane the Elder (1589–1655), a former Secretary of State and a member for Wilton

* Sir Philip Stapleton (1603–1647), a colonel of horse who commanded the Earl of Essex's bodyguard and a brigade of cavalry at the Battle of Edgehill

The Battle of Edgehill (or Edge Hill) was a pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642.

All attempts at constitutional compromise between ...

, a member for Boroughbridge

Boroughbridge () is a town and civil parish in the Harrogate district of North Yorkshire, England. Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is north-west of the county town of York. Until a bypass was built the town lay on t ...

*Sir William Waller

Sir William Waller JP (c. 159719 September 1668) was an English soldier and politician, who commanded Parliamentarian armies during the First English Civil War, before relinquishing his commission under the 1645 Self-denying Ordinance.

...

(''c.'' 1597–1668), a strict Presbyterian and a major-general of the parliamentary forces, one of the members for Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

*Sir Gilbert Gerard

Sir Gilbert Gerard (died 4 February 1593) was a prominent lawyer, politician, and landowner of the Tudor period. He was returned six times as a member of the English parliament for four different constituencies. He was Attorney-General for more ...

(1587–1670), a member for Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a historic county in southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the ceremonial county of Greater London, with small sections in neighbour ...

, paymaster of the Parliamentary army and from 1648 to 1649 Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

The chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster is a ministerial office in the Government of the United Kingdom. The position is the second highest ranking minister in the Cabinet Office, immediately after the Prime Minister, and senior to the Minist ...

* Sir William Airmine (1593–1651), a member for Grantham

Grantham () is a market and industrial town in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England, situated on the banks of the River Witham and bounded to the west by the A1 road. It lies some 23 miles (37 km) south of the Lincoln a ...

, later a member of the Council of State

* Sir Arthur Haselrig (1601–1661), a knight of the shire

Knight of the shire ( la, milites comitatus) was the formal title for a member of parliament (MP) representing a county constituency in the British House of Commons, from its origins in the medieval Parliament of England until the Redistributio ...

for Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire ...

; following the Restoration he was imprisoned in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sep ...

and died there.

*Henry Vane the Younger

Sir Henry Vane (baptised 26 March 161314 June 1662), often referred to as Harry Vane and Henry Vane the Younger to distinguish him from his father, Henry Vane the Elder, was an English politician, statesman, and colonial governor. He was bri ...

(1613–1662), a member for Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually abbreviated to Hull, is a port city and unitary authority in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, inland from the North Sea and south- ...

; although he took no part in the regicide, in 1662 he was charged with high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and beheaded

* John Crew (1598–1679), a member for Brackley

Brackley is a market town and civil parish in West Northamptonshire, England, bordering Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire, from Oxford and from Northampton. Historically a market town based on the wool and lace trade, it was built on the inter ...

and a Justice of the Peace

A justice of the peace (JP) is a judicial officer of a lower or '' puisne'' court, elected or appointed by means of a commission ( letters patent) to keep the peace. In past centuries the term commissioner of the peace was often used with the s ...

, was later created Baron Crew by King Charles II

*Robert Wallop

Robert Wallop (20 July 1601 – 19 November 1667) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times from 1621 to 1660. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil War and was one of the regicides of King Char ...

(1601–1667), a member for Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

*Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Andov ...

, was later one of the Commissioners who sat in judgment at the trial of Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

*Oliver St John

Sir Oliver St John (; c. 1598 – 31 December 1673) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1640-53. He supported the Parliamentary cause in the English Civil War.

Early life

St John was the son of Oliver S ...

(''c.'' 1598–1673), a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and givin ...

and judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

who was married to a cousin of Oliver Cromwell; he was a member for Totnes

Totnes ( or ) is a market town and civil parish at the head of the estuary of the River Dart in Devon, England, within the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is about west of Paignton, about west-southwest of Torquay and abo ...

and became Solicitor General

*Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three ...

(1599–1658), a member for Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a university city and the county town in Cambridgeshire, England. It is located on the River Cam approximately north of London. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, the population of Cambridge was 145,700. Cambridge bec ...

, later Lord Protector

Lord Protector (plural: ''Lords Protector'') was a title that has been used in British constitutional law for the head of state. It was also a particular title for the British heads of state in respect to the established church. It was sometimes ...

* Samuel Browne (''c.'' 1598–1668), a member for Clifton, Dartmouth and Hardness

* Serjeant John Glynne (1602–1666), a member for Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, B ...

and Recorder of London

The Recorder of London is an ancient legal office in the City of London. The Recorder of London is the senior circuit judge at the Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey), hearing trials of criminal offences. The Recorder is appointed by the Cr ...

David Masson states that the Earl of Essex, the Lord General, was opposed to the formation of the committee as it was constituted because "there can be no doubt that the object was that the management of the war should be less in Essex's hands than it had been".

Administration

The Committee met inDerby House

The College of Arms, or Heralds' College, is a royal corporation consisting of professional officers of arms, with jurisdiction over England, Wales, Northern Ireland and some Commonwealth realms. The heralds are appointed by the British Sovereig ...

at three o'clock every day of the week—including Sundays. Attendance in 1644 was patchy, since before the enactment of the Self-denying Ordinance

The Self-denying Ordinance was passed by the English Parliament on 3 April 1645. All members of the House of Commons or Lords who were also officers in the Parliamentary army or navy were required to resign one or the other, within 40 days fr ...

, many of the members of the Committee had commands in the field. Warwick, for example, was the Lord High Admiral. The more active and influential members on the Committee were Lord Wharton and Henry Vane the Younger, and Lord Warriston for the Scots.

The Committee had to accommodate several factions within its ranks, and jealousies and personal animosities between some of its members, such as Waller and Essex. It was also subject to control by Parliament (though the need to pass legislation or resolutions through both Houses meant that the Committee could control matters day by day without much interference).

Its greatest achievement was the establishment of the New Model Army

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Th ...

, and the maintenance of this army and other forces in the field until King Charles was defeated in 1646. The Committee provided a continuity of policy and administration which the King could not match.

Dissolution

On 27 April 1646, Charles left Oxford and surrendered to the

On 27 April 1646, Charles left Oxford and surrendered to the Covenanter

Covenanters ( gd, Cùmhnantaich) were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland, and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. The name is derived from '' Covena ...

army outside Newark. A few days later, they withdrew north to Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

, taking the king with them despite the furious objections of the English. In July, the Committee presented Charles with the Newcastle Propositions, which included his acceptance of a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their n ...

union between the kingdoms. Once Charles rejected the terms, it left the Covenanters in a difficult position; keeping him was too dangerous since many Scots, regardless of political affiliation, wanted him restored to the throne. On 28 January 1647, they handed Charles over to Parliament in return for £400,000 and retreated into Scotland.

The Committee was now dissolved but its English members continued to sit as the Derby House Committee, dominated by Holles and moderate MPs, many of whom were Presbyterian. Internal political conflict was exacerbated by economic crisis, caused by the war and a failed 1646 harvest. By March 1647, the New Model was owed more than £3 million in unpaid wages; led by Holles, Parliament ordered it to Ireland, stating only those who agreed to go would be paid. When regimental representatives or Agitators

The Agitators were a political movement as well as elected representatives of soldiers, including members of the New Model Army under Lord General Fairfax, during the English Civil War. They were also known as ''adjutators''. Many of the ideas o ...

supported by the Army Council demanded full payment for all in advance, it was disbanded but the army refused to comply.

In response, Holles and his allies formed a new Committee of Safety and attempted to raise a new army commanded by Edward Massie

Sir Edward Massey () was an English soldier and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1646 and 1674. He fought for the Parliamentary cause for the first and second English Civil Wars before changing allegiance and ...

. On 21 July, eight peers and fifty-seven Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independe ...

MPs left London and took refuge with the New Model; on 6 August, the army occupied the city, dissolved the Committee and issued a list of Eleven Members who they wanted removed from Parliament.

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * Attribution *Further reading

* * {{cite web, last=Plant , first=David , date=17 December 2006 , url=http://www.british-civil-wars.co.uk/glossary/committee-both-kingdoms.htm , title=The Committee for Both Kingdoms , publisher=British Civil Wars & Commonwealth website English Civil War Parliament of England Covenanters 1643 establishments in England