Colombia–Panama border on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Colombia–Panama border is the international boundary between Colombia and

The Colombia–Panama border is the international boundary between Colombia and

The border starts in the north at Cabo Tiburón on the

The border starts in the north at Cabo Tiburón on the

Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cost ...

. It also splits the Darién Gap

The Darién Gap (, , es, Tapón del Darién , ) is a geographic region between the North and South American continents within Central America, consisting of a large watershed, forest, and mountains in Panama's Darién Province and the norther ...

, a break across the South American and North American continents. This large watershed, forest, and mountainous area is in the north-western portion of Colombia's Chocó Department

Choco Department is a department of Western Colombia known for its large Afro-Colombian population. It is in the west of the country, and is the only Colombian department to have coastlines on both the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean. It ...

and south-eastern portion of Panama's Darién Province

Darién (, , ) is a province in Panama whose capital city is La Palma. With an area of , it is located at the eastern end of the country and bordered to the north by the province of Panamá and the region of Kuna Yala. To the south, it is border ...

.

There is also a gap in the Pan-American Highway

The Pan-American Highway (french: (Auto)route panaméricaine/transaméricaine; pt, Rodovia/Auto-estrada Pan-americana; es, Autopista/Carretera/Ruta Panamericana) is a network of roads stretching across the Americas and measuring about in to ...

that begins in Turbo

In an internal combustion engine, a turbocharger (often called a turbo) is a forced induction device that is powered by the flow of exhaust gases. It uses this energy to compress the intake gas, forcing more air into the engine in order to pro ...

, Colombia, and ends in Yaviza Yaviza is a town and corregimiento in Pinogana District, Darién Province, Panama with a population of 4,441 as of 2010.

Location

The town marks the southeastern end of the northern half of the Pan-American Highway, at the north end of the Dar ...

, Panama, and is long. Road-building through this area is expensive and the environmental cost is high, and no political consensus in favour of road construction has emerged.

Description

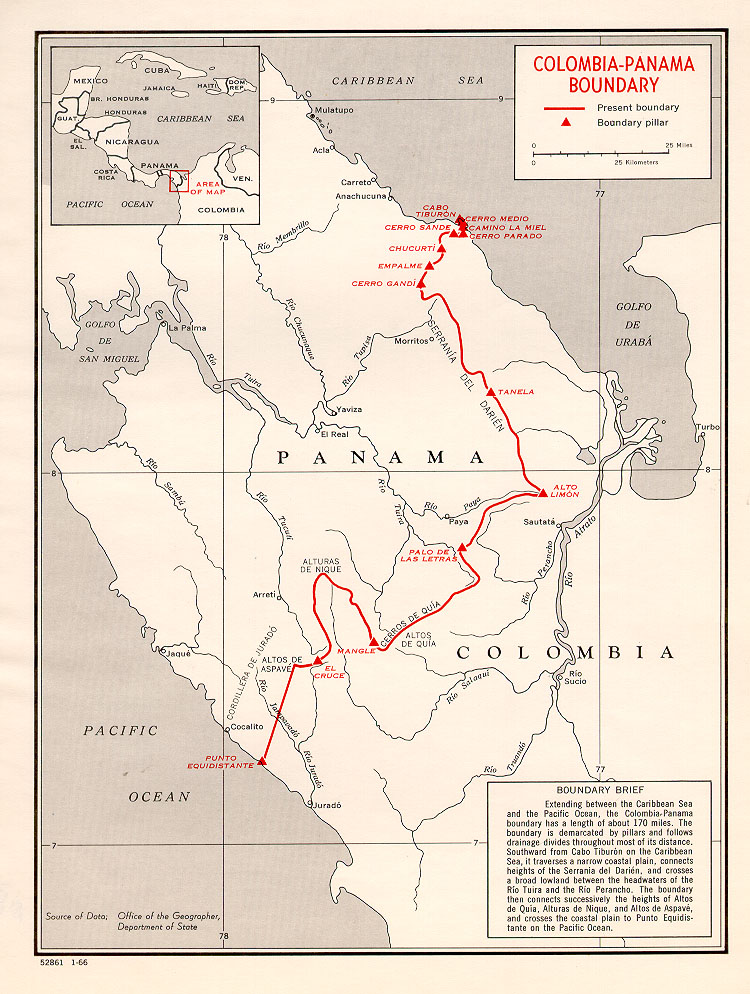

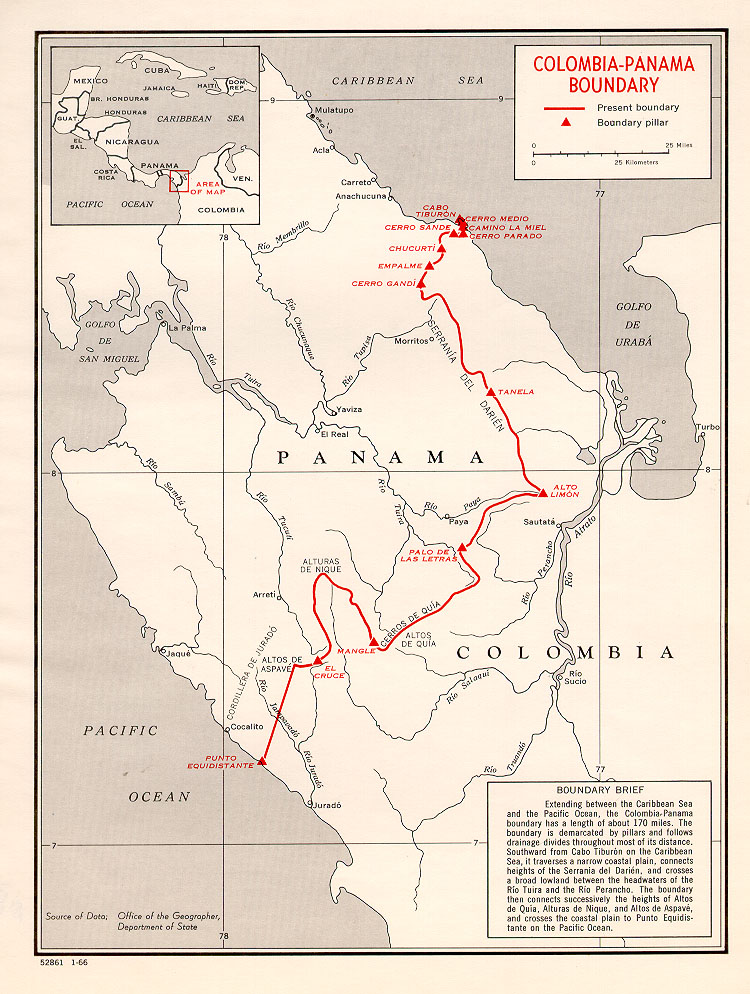

The border starts in the north at Cabo Tiburón on the

The border starts in the north at Cabo Tiburón on the Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea ( es, Mar Caribe; french: Mer des Caraïbes; ht, Lanmè Karayib; jam, Kiaribiyan Sii; nl, Caraïbische Zee; pap, Laman Karibe) is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean in the tropics of the Western Hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico ...

coast and proceeds overland to the south-west and then south-east via various peaks of the Serranía del Darién

The Serranía del Darién is a small mountain range on the border between Colombia and Panamá in the area called the Darién Gap. It is located in the southeastern part of the Darién Province of Panamá and the northwestern part of the Chocó ...

range as far as Alto Limón. It then proceeds south-westwards, except for a northwards Colombian protrusion in the vicinity of Cerro Pirre, terminating in the south on the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

coast at Punto Equidistante.

The geography of the Colombian side is dominated primarily by the river delta

A river delta is a landform shaped like a triangle, created by deposition of sediment that is carried by a river and enters slower-moving or stagnant water. This occurs where a river enters an ocean, sea, estuary, lake, reservoir, or (more rar ...

of the Atrato River

The Atrato River () is a river of northwestern Colombia. It rises in the slopes of the Western Cordillera and flows almost due north to the Gulf of Urabá (or Gulf of Darién), where it forms a large, swampy delta. Its course crosses the Ch ...

, which creates a flat marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

land at least wide, half of this being swampland. The Serranía del Baudó

The Serranía del Baudó is a coastal mountain range on the Pacific coast of Colombia. It is separated from the West Andes by the Atrato valley where the Atrato River flows and Quibdó is located. From the south the range extends from the Baud ...

range extends along Colombia's Pacific coast and into Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cost ...

. The Panamanian side, in sharp contrast, is a mountainous rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainforest, ...

, with terrain reaching from in the valley floors to at the tallest peak (Cerro Tacarcuna, in the Serranía del Darién).

History

Pre-Columbian history

Archaeological knowledge of this area has received relatively little attention compared to its adjoining neighbors to the north and south, despite the fact that scholars such asMax Uhle

Friedrich Max Uhle (25 March 1856 – 11 May 1944) was a German archaeologist, whose work in Peru, Chile, Ecuador and Bolivia at the turn of the Twentieth Century had a significant impact on the practice of archaeology of South America.

Biogr ...

, William Henry Holmes

William Henry Holmes (December 1, 1846 – April 20, 1933), known as W. H. Holmes, was an American explorer, anthropologist, archaeologist, artist, scientific illustrator, cartographer, mountain climber, geologist and museum curator and direc ...

, C. V. Hartman, and George Grant MacCurdy

George Grant MacCurdy (April 17, 1863 – November 15, 1947) was an American anthropologist, born at Warrensburg, Mo., where he graduated from the State Normal School in 1887, after which he attended Harvard (AB, 1893; AM, 1894); then studied in ...

undertook studies of archaeological sites and collections here over a century ago that were augmented by further research by Samuel Kirkland Lothrop

Samuel Kirkland Lothrop (July 6, 1892 – January 10, 1965) was an American archaeologist and anthropologist who specialized in Central and South American Studies. His two-volume 1926 work ''Pottery of Costa Rica and Nicaragua'' is regarded as a ...

, John Alden Mason

John Alden Mason (January 14, 1885 – November 7, 1967) was an American archaeological anthropologist and linguist.

Mason was born in Orland, Indiana, but grew up in Philadelphia's Germantown. He received his undergraduate degree from the Uni ...

, Doris Zemurray Stone

Doris Zemurray Stone (November 19, 1909 – October 21, 1994) was an archaeologist and ethnographer, specializing in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica and the so-called "Intermediate Area" of lower Central America. She served as the director of the Natio ...

, William Duncan Strong William Duncan Strong (1899–1962) was an American archaeologist and anthropologist noted for his application of the direct historical approach to the study of indigenous peoples of North and South America.

Early life and education

Strong was bor ...

, Gordon Willey

Gordon Randolph Willey (7 March 1913 – 28 April 2002) was an American archaeologist who was described by colleagues as the "dean" of New World archaeology.Sabloff 2004, p.406 Willey performed fieldwork at excavations in South America, Central ...

, and others in the early 20th century. One of the reasons for the relative lack of attention is the lack of research by locals themselves into ancestral monuments and architecture and a long history of ethnocentric

Ethnocentrism in social science and anthropology—as well as in colloquial English discourse—means to apply one's own culture or ethnicity as a frame of reference to judge other cultures, practices, behaviors, beliefs, and people, instead of ...

perceptions by Western scholars of what represents civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

. There are a large number of sites with impressive platform mounds, plazas, paved roads, stone sculpture, and artifacts made from jade

Jade is a mineral used as jewellery or for ornaments. It is typically green, although may be yellow or white. Jade can refer to either of two different silicate minerals: nephrite (a silicate of calcium and magnesium in the amphibole group of ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile m ...

, and ceramic materials.

The Darién Gap is home to the Embera-Wounaan

The Embera–Wounaan are a semi-nomadic indigenous people in Panama living in Darién Province on the shores of the Chucunaque, Sambú, Tuira Rivers and its waterways. The Embera-Wounaan were formerly and widely known by the name Chocó, an ...

and Kuna

Kuna may refer to:

Places

* Kuna, Idaho, a town in the United States

** Kuna Caves, a lava tube in Idaho

* Kuna Peak, a mountain in California

* , a village in the Orebić municipality, Croatia

* , a village in the Konavle municipality, Croatia ...

(and the former home of the Cueva people

The Cueva were an indigenous tribe which was one of the first in Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a List of transcontinental countries#North America and Sout ...

before the 16th century). Travel is often by specialized canoes ( piragua). On the Panamanian side, La Palma

La Palma (, ), also known as ''La isla bonita'' () and officially San Miguel de La Palma, is the most north-westerly island of the Canary Islands, Spain. La Palma has an area of making it the fifth largest of the eight main Canary Islands. Th ...

is the capital of the province and the main cultural centre. Corn

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. The ...

, cassava

''Manihot esculenta'', commonly called cassava (), manioc, or yuca (among numerous regional names), is a woody shrub of the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, native to South America. Although a perennial plant, cassava is extensively cultivated ...

, plantains

Plantain may refer to:

Plants and fruits

* Cooking banana, banana cultivars in the genus ''Musa'' whose fruits are generally used in cooking

** True plantains, a group of cultivars of the genus ''Musa''

* ''Plantaginaceae'', a family of floweri ...

, and banana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

s are staple crops wherever land is developed.

The Cunas were living in what is now Northern Colombia and the Darién Province of Panama at the time of the Spanish invasion, and only later began to move westward due to a conflict with the Spanish and other indigenous groups. Centuries before the conquest, the Cunas arrived in South America as part of a Chibchan

The Chibchan languages (also Chibchan, Chibchano) make up a language family indigenous to the Isthmo-Colombian Area, which extends from eastern Honduras to northern Colombia and includes populations of these countries as well as Nicaragua, Cost ...

migration moving east from Central America. At the time of the Spanish invasion, they were living in the region of Uraba and near the borders of what are now Antioquia and Caldas. The Cuna themselves attribute their migrations to conflicts with other chiefdoms, and their migration to nearby islands to the mosquito populations on the mainland.

European settlement

Alonso de Ojeda

Alonso de Ojeda (; c. 1466 – c. 1515) was a Spanish explorer, governor and conquistador. He travelled through modern-day Guyana, Venezuela, Trinidad, Tobago, Curaçao, Aruba and Colombia. He navigated with Amerigo Vespucci who is famous for ...

and Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for having crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an e ...

explored the coast of Colombia in 1500 and 1501. They spent the most time in the Gulf of Urabá

The Gulf of Urabá is a gulf on the northern coast of Colombia. It is part of the Caribbean Sea. It is a long, wide inlet located on the coast of Colombia, close to the connection of the continent to the Isthmus of Panama. The town of Turbo, Co ...

, where they made contact with the Cunas. The regional border was initially created in 1508 after royal decree, to separate the colonial governorships of Castilla de Oro

Castilla de Oro or del Oro () was the name given by the Spanish settlers at the beginning of the 16th century to the Central American territories from the Gulf of Urabá, near today's Colombian-Panamanian border, to the Belén River. Beyond th ...

and Nueva Andalucía, using the River Atrato as the boundary between the two governorships.

Vasco Núñez de Balboa

Vasco Núñez de Balboa (; c. 1475around January 12–21, 1519) was a Spanish explorer, governor, and conquistador. He is best known for having crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific Ocean in 1513, becoming the first European to lead an e ...

heard of the South Sea from locals while sailing along the Caribbean coast. On 25 September 1513 he saw the Pacific. In 1519 the town of Panamá was founded near a small indigenous settlement on the Pacific coast. After the European discovery of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = National seal

, national_motto = "Firm and Happy f ...

, it developed into an important port of trade and became an administrative centre. In 1671 the Welsh pirate Henry Morgan

Sir Henry Morgan ( cy, Harri Morgan; – 25 August 1688) was a privateer, plantation owner, and, later, Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica. From his base in Port Royal, Jamaica, he raided settlements and shipping on the Spanish Main, becoming w ...

crossed the Isthmus of Panamá from the Caribbean side and destroyed the city. The town was relocated some kilometers to the west at a small peninsula. The ruins of the old town, Panamá Viejo

Panamá Viejo (English: "Old Panama"), also known as Panamá la Vieja, is the remaining part of the original Panama City, the former capital of Panama, which was destroyed in 1671 by the Welsh privateer Henry Morgan. It is located in the suburbs ...

, are preserved and were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

in 1997.

The area of modern Colombia (then including Panama) was organised into the Presidency of New Granada in 1564, later upgraded to a Viceroyalty in 1718, being demoted the following year, but restored as a Viceroyalty in 1739. New Granada encompassed the territory of modern Panama, Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador. Silver and gold from the viceroyalty of Peru

The Viceroyalty of Peru ( es, Virreinato del Perú, links=no) was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed fro ...

were transported overland across the Darién isthmus by Spanish Silver Train The Spanish Silver Train was an improvised trail used to transport silver from Potosí, Peru across the isthmus of Panama in order to ship it to Spain via the Spanish treasure fleet. The silver was usually unloaded in Panama City, then put in mule ...

to Porto Bello, where Spanish treasure fleet

The Spanish treasure fleet, or West Indies Fleet ( es, Flota de Indias, also called silver fleet or plate fleet; from the es, label=Spanish, plata meaning "silver"), was a convoy system of sea routes organized by the Spanish Empire from 1566 to ...

s shipped them to Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

and Cádiz

Cádiz (, , ) is a city and port in southwestern Spain. It is the capital of the Province of Cádiz, one of eight that make up the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Cádiz, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Western Europe, ...

from 1707. Lionel Wafer

Lionel Wafer (1640–1705) was a Welsh explorer, buccaneer and privateer.

A ship's surgeon, Wafer made several voyages to the South Seas and visited Maritime Southeast Asia in 1676. In 1679 he sailed again as a surgeon, soon after settling in ...

spent four years between 1680 and 1684 among the Cuna Indians

The Guna, are an Indigenous people of Panama and Colombia. In the Guna language, they call themselves ''Dule'' or ''Tule'', meaning "people", and the name of the language is ''Dulegaya'', literally "people-mouth".

The term was in the language ...

.

Scotland tried to establish a settlement in 1698 through the Darien scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing ''New Caledonia'', a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The plan was for the co ...

, independent Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

's one major attempt at colonialism. The first expedition of five ships (''Saint Andrew'', ''Caledonia'', ''Unicorn'', ''Dolphin'', and ''Endeavour'') set sail from Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by '' Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

on July 14, 1698, with around 1,200 people on board. Their orders were "to proceed to the Bay of Darien, and make the Isle called the Golden Island ... some few leagues to the leeward of the mouth of the great River of Darien ... and there make a settlement on the mainland". After calling at Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater ...

, the fleet made landfall off the coast of Darien on November 2. The settlers christened their new home "New Caledonia".

The aim was for the colony to have an overland route that connected the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. From its contemporary time to the present day, claims have been made that the undertaking was beset by poor planning and provisioning, divided leadership, a poor choice of trade goods, devastating epidemics of disease, reported attempts by the East India Company to frustrate it, as well as a failure to anticipate the Spanish Empire's military response. It was finally abandoned in March 1700 after a siege by Spanish forces, which also blockaded the harbour. As the Company of Scotland was backed by approximately 20% of all the money circulating in Scotland, its failure left the entire Lowlands in substantial financial ruin and English financial incentives were a factor in persuading those in power to support the 1707 Acts of Union. According to this argument, the Scottish establishment (landed aristocracy and mercantile elites) considered that their best chance of being part of a major power would be to share the benefits of England's international trade and the growth of the English overseas possessions, so its future would have to lie in unity with England. Furthermore, Scotland's nobles were almost bankrupted by the Darien fiasco. The land where the Darien colony was built, in the modern province of Guna Yala, is virtually uninhabited today.

Post-colonial period

In 1810, Colombia declared independence from Spain, and united with Venezuela (and later Panama and Ecuador) to formGran Colombia

Gran Colombia (, "Great Colombia"), or Greater Colombia, officially the Republic of Colombia ( Spanish: ''República de Colombia''), was a state that encompassed much of northern South America and part of southern Central America from 1819 to ...

in 1819. The union split however in 1829–30, with Colombia (including Panama) separating off as the Republic of New Granada

The Republic of New Granada was a 1831–1858 centralist unitary republic consisting primarily of present-day Colombia and Panama with smaller portions of today's Costa Rica, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru and Brazil. On 9 May 1834, the national flag ...

. In 1858 this was renamed the Granadine Confederation

The Granadine Confederation ( es, Confederación Granadina) was a short-lived federal republic established in 1858 as a result of a constitutional change replacing the Republic of New Granada. It consisted of the present-day nations of Colombia a ...

and in 1855 the state of Panama was created within it, with the border with the rest of the Confederation fixed the same years. The federal country was renamed the United States of Colombia

United States of Colombia () was the name adopted in 1863 by the for the Granadine Confederation, after years of civil war. Colombia became a federal state itself composed of nine "sovereign states.” It comprised the present-day nations ...

in 1863, however the country was centralised in 1885. Panamanian separatism grew, with the country declaring independence in 1903 with the backing the United States, who wished to build a canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface fl ...

across the country.

On April 6, 1914 Colombia and the United States signed a treaty which recognised the 1855 Colombia–Panama border. Colombia and Panama concluded the Victoria-Velez Treaty in Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city of Colombia, and one of the largest ...

on August 20, 1924, a border treaty signed by the Foreign Ministers of Panama, Nicolas Victoria, and Colombia, Jorge Velez. This treaty was officially registered in the Register No. 814 of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

Treaty Series, on August 17, 1925. The border was again based on the same Colombian law of June 9, 1855.De Leon, Raquel Maria. '' Boundaries and Borders'. Panama. 1965. The border was then demarcated on the ground via series of pillars, with the final alignment confirmed on June 17, 1938.

Migrant crises

In May 2016, Panama closed key border crossings to prevent undocumented migrants from Cuba and Africa entering the country. Cubans entering the United States are typically able to receive residency under theCuban Adjustment Act

The Cuban Adjustment Act (in Spanish, Ley de Ajuste Cubano), Public Law 89-732, is a United States federal law enacted on November 2, 1966. Passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson, the law applie ...

of 1966, making Puerto Obaldia a popular crossing point for Cuban migrants traveling to the United States. The decision to close the border was made because Costa Rica and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the countr ...

had closed their borders to Cubans heading north. The closing of the Panama-Colombia border resulted in a number of migrants being stranded in Turbo, a transit point for migrants. Some of the Cubans began protesting, demanding to be airlifted to Mexico.

See also

*Darién Gap

The Darién Gap (, , es, Tapón del Darién , ) is a geographic region between the North and South American continents within Central America, consisting of a large watershed, forest, and mountains in Panama's Darién Province and the norther ...

* Darien scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing ''New Caledonia'', a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The plan was for the co ...

* Gulf of Darién

* Lionel Wafer

Lionel Wafer (1640–1705) was a Welsh explorer, buccaneer and privateer.

A ship's surgeon, Wafer made several voyages to the South Seas and visited Maritime Southeast Asia in 1676. In 1679 he sailed again as a surgeon, soon after settling in ...

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Colombia-Panama border Borders of Colombia Borders of Panama International borders