Colloquy of Marburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

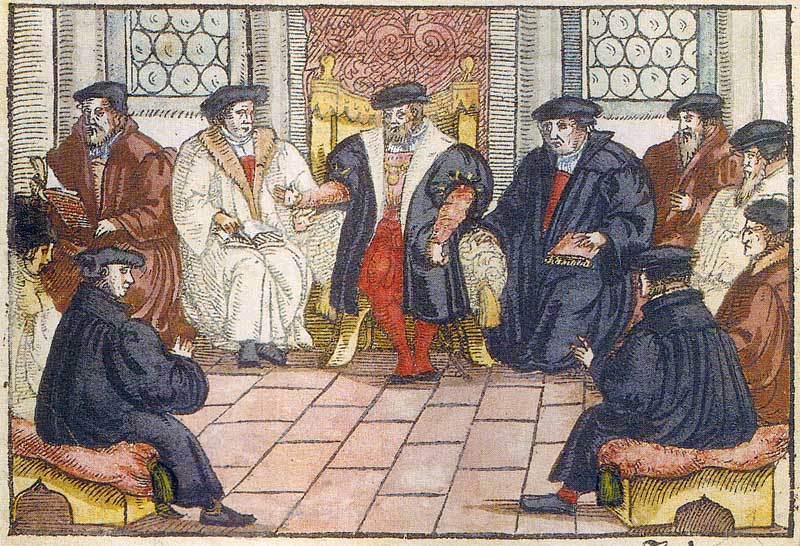

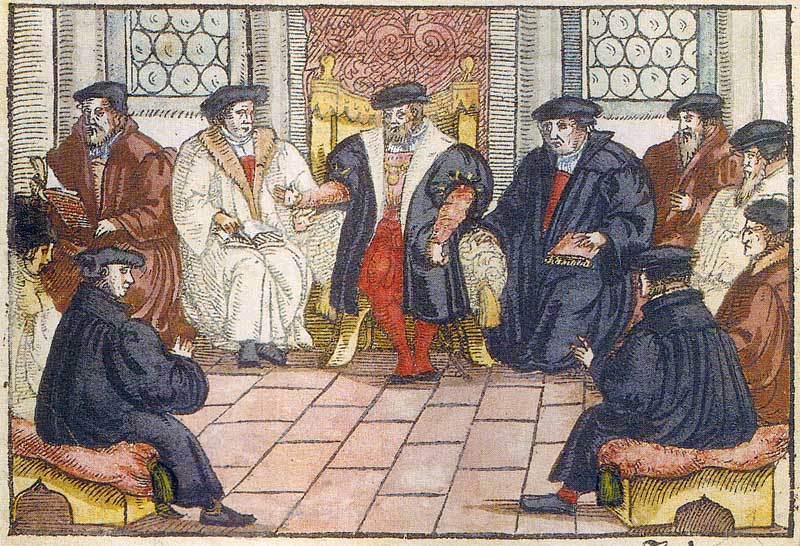

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at

Although the two prominent reformers, Luther and Zwingli, found a consensus on fourteen theological points, they could not find agreement on the fifteenth point pertaining to the

Although the two prominent reformers, Luther and Zwingli, found a consensus on fourteen theological points, they could not find agreement on the fifteenth point pertaining to the

The Marburg Articles (1529)

(Text of the 15 Marburg Articles), German History in Documents and Images, Translated by Ellen Yutzy Glebe, from the German source: ''D. Martin Luthers Werke'', Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Band 30, Teil 3. Weimar, 1910, pp. 160–71.

''Huldreich Zwingli, the Reformer of German Switzerland''

edited by Samuel Macauley Jackson et al., 1903. Online from

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at

The Marburg Colloquy was a meeting at Marburg Castle

The Marburger Schloss (or ''Marburg castle''), also known as Landgrafenschloss Marburg, is a castle in Marburg, Hesse, Germany, located on top of Schlossberg (287 m NAP). Built in the 11th century as a fort, it became the first residence o ...

, Marburg

Marburg ( or ) is a university town in the German federal state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district (''Landkreis''). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has a population of approxima ...

, Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major historic cities are Dar ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, which attempted to solve a disputation

In the scholastic system of education of the Middle Ages, disputations (in Latin: ''disputationes'', singular: ''disputatio'') offered a formalized method of debate designed to uncover and establish truths in theology and in sciences. Fixed ru ...

between Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and Ulrich Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

over the Real Presence

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

There are a number of Christian denomin ...

of Christ in the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. It took place between 1 October and 4 October 1529. The leading Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

reformers of the time attended at the behest of Philip I of Hessen. Philip's primary motivation for this conference was political; he wished to unite the Protestant states in political alliance, and to this end, religious harmony was an important consideration.

After the Diet of Speyer had confirmed the edict of Worms

The Diet of Worms of 1521 (german: Reichstag zu Worms ) was an imperial diet (a formal deliberative assembly) of the Holy Roman Empire called by Emperor Charles V and conducted in the Imperial Free City of Worms. Martin Luther was summoned to t ...

, Philip I felt the need to reconcile the diverging views of Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Protestant Reformation and the namesake of Lutherani ...

and Ulrich Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland, born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system. He attended the Univ ...

in order to develop a unified Protestant theology. Besides Luther and Zwingli, the reformers Stephan Agricola Stephan Agricola (c. 1491–1547) was a Lutheran church reformer. Born in Abensberg, at a young age he joined the Augustinian order. As a monk, he studied Augustine deeply.Henry Eyster JacobsLutheran Cyclopediap. 6, "Agricola, Stephen" As a student, ...

, Johannes Brenz

Johann (Johannes) Brenz (24 June 1499 – 11 September 1570) was a German Lutheran theologian and the Protestant Reformer of the Duchy of Württemberg.

Early advocacy of the Reformation

Brenz was born in the then Imperial City of Weil der S ...

, Martin Bucer, Caspar Hedio

Caspar Hedio, also written as Kaspar Hedio, Kaspar Heyd, Kaspar Bock or Kaspar Böckel (Ettlingen, 1494 - Strasbourg, 17 October 1552) was a German historian, theologian and Protestant reformer.

He was born into a prosperous family and attende ...

, Justus Jonas

Justus Jonas, the Elder (5 June 1493 – 9 October 1555), or simply Justus Jonas, was a German Lutheran theologian and reformer. He was a Jurist, Professor and Hymn writer. He is best known for his translations of the writings of Martin Luther ...

, Philipp Melanchthon, Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius (also ''Œcolampadius'', in German also Oekolampadius, Oekolampad; 1482 – 24 November 1531) was a German Protestant reformer in the Calvinist tradition from the Electoral Palatinate. He was the leader of the Protestant ...

, Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander (; 19 December 1498 – 17 October 1552) was a German Lutheran theologian and Protestant reformer.

Career

Born at Gunzenhausen, Ansbach, in the region of Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before ...

, and Bernhard Rothmann

Bernhard (or Bernard) Rothmann (c. 1495 – c. 1535) was a 16th-century radical and Anabaptist leader in the city of Münster. He was born in Stadtlohn, Westphalia, around 1495.

Overview

In the late 1520s Bernard Rothmann became the leader for re ...

participated in the meeting.

If Philip wanted the meeting to be a symbol of Protestant unity he was disappointed. Both Luther and Zwingli fell out over the sacrament of the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

.

Background

Philip of Hesse had a political motivation to unify all the leading Protestants because he believed that as a divided entity they were vulnerable to Charles V. As a unified force, they would appear to be more powerful. Religious harmony was vital amongst the Protestants for there to be a unification.Participants

The colloquy

Although the two prominent reformers, Luther and Zwingli, found a consensus on fourteen theological points, they could not find agreement on the fifteenth point pertaining to the

Although the two prominent reformers, Luther and Zwingli, found a consensus on fourteen theological points, they could not find agreement on the fifteenth point pertaining to the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

. Timothy George

Timothy George (born 9 January 1950) is an American theologian and journalist. He became the founding dean of Beeson Divinity School at the school's inception in 1988 and was the dean from 1989–2019, now serving as Research Professor of Divinity ...

, an author and professor of Church History, summarized the incompatible views, "On this issue, they parted without having reached an agreement. Both Luther and Zwingli agreed that the bread in the Supper was a sign. For Luther, however, that which the bread signified, namely the body of Christ, was present "in, with, and under" the sign itself. For Zwingli, though, sign and thing signified were separated by a distance—the width between heaven and earth."

Underlying this disagreement was their theology of Christ. Luther believed that the human body of Christ was ubiquitous (present in all places) and so present in the bread and wine. This was possible because the attributes of God infused Christ's human nature. Luther emphasized the oneness of Christ's person. Zwingli, who emphasized the distinction of the natures, believed that while Christ in his deity was omnipresent, Christ's human body could only be present in one place, that is, at the right hand of the Father. The executive editor for Christianity Today magazine carefully detailed the two views that would forever divide the Lutheran and Reformed view of the Supper:

Near the end of the colloquy when it was clear an agreement would not be reached, Philipp asked Luther to draft a list of doctrines all that both sides agreed upon. The Marburg Articles

Marburg ( or ) is a university town in the German federal state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district (''Landkreis''). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has a population of approximate ...

, based on what would become the Articles of Schwabach

Beginning in July 1529,Johann Michael Reu, ''The Augsburg Confession'' (1930), p. 28. Philipp Melanchthon, along with Martin Luther and probably Justus Jonas, wrote the Articles of Schwabach (so named because they were presented at the Convention ...

, had 15 points, and every person at the colloquy could agree on the first 14. The 15th article of the Marburg Articles reads:

The failure to find agreement resulted in strong emotions on both sides. "When the two sides departed, Zwingli cried out in tears, 'There are no people on earth with whom I would rather be at one than the utheranWittenbergers.'" Because of the differences, Luther initially refused to acknowledge Zwingli and his followers as Christians, though following the colloquy the two Reformers showed relatively more mutual respect in their writings. G. R. Potter, ''Zwingli'', Cambridge University Press, 1976

Aftermath

At the laterDiet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the German city of Augsburg. Both an Imperial City and the residence of the Augsburg prince-bishops, the town had hosted the Estates in many such sessi ...

, the Zwinglians and Lutherans again explored the same territory as that covered in the Marburg Colloquy and presented separate statements which showed the differences in opinion.

See also

* First war of Kappel (1529)References

External links

The Marburg Articles (1529)

(Text of the 15 Marburg Articles), German History in Documents and Images, Translated by Ellen Yutzy Glebe, from the German source: ''D. Martin Luthers Werke'', Kritische Gesamtausgabe, Band 30, Teil 3. Weimar, 1910, pp. 160–71.

''Huldreich Zwingli, the Reformer of German Switzerland''

edited by Samuel Macauley Jackson et al., 1903. Online from

Google Books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

* Phillip Cary. ''Luther: Gospel, Law and Reformation'', ound recording Lecture 14. 2004, The Teaching Company Limited Partnership

*

{{Authority control

1529 in Europe

Marburg

Marburg ( or ) is a university town in the German federal state (''Bundesland'') of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district (''Landkreis''). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has a population of approxima ...

History of Hesse

Lutheran Eucharistic theology

Marburg

Martin Luther