Christopher Cradock on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In May Cradock shifted his flag to the predreadnought battleship where he took charge of experiments that the RN was conducting with launching aircraft from ships. Commander

In May Cradock shifted his flag to the predreadnought battleship where he took charge of experiments that the RN was conducting with launching aircraft from ships. Commander

When the preliminary warning for war with Imperial Germany reached Cradock on 27 July, there were two German

When the preliminary warning for war with Imperial Germany reached Cradock on 27 July, there were two German

Cradock found Spee's force off

Cradock found Spee's force off

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Sir Christopher "Kit" George Francis Maurice Cradock (2 July 1862 – 1 November 1914) was an English senior officer of the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

. He earned a reputation for great gallantry.

Appointed to the royal yacht, he was close to the British royal family. Prior to the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, his combat service during the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

and the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

was all ashore. Appointed Commander-in-Chief of the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

before the war, his mission was to protect Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

merchant shipping by hunting down German commerce raider

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

s.

Late in 1914 he was tasked to search for and destroy the East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the ...

of the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

as it headed home around the tip of South America. Believing that he had no choice but to engage the squadron in accordance with his orders, despite his numerical and tactical inferiority, he was killed during the Battle of Coronel

The Battle of Coronel was a First World War Imperial German Navy victory over the Royal Navy on 1 November 1914, off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. The East Asia Squadron (''Ostasiengeschwader'' or ''Kreuzergeschwader'') ...

off the coast of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

in November when the German ships sank his flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

.

Early life and career

Cradock was born atHartforth

Hartforth is a small village in the Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire, England. The village is situated approximately south-west from the market town of Darlington, and is part of the civil parish of Gilling with Hartforth and Sedbury ...

, Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

, North Riding of Yorkshire

The North Riding of Yorkshire is a subdivision of Yorkshire, England, alongside York, the East Riding and West Riding. The riding's highest point is at Mickle Fell with 2,585 ft (788 metres).

From the Restoration it was used as ...

, on 2 July 1862, the fourth son of Christopher and Georgina Cradock (née Duff). He joined the Royal Navy's cadet training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

on 15 January 1875 and was appointed to the armoured corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the slo ...

of the Mediterranean Station

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

on 22 December 1876. Cradock was promoted to midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest rank, in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Canada (Naval Cadet), Australia, Bangladesh, Namibia, New Zealand, South Afr ...

on 22 December 1877 and was present when the British occupied the island of Cyprus

Cyprus is an island in the Eastern Basin of the Mediterranean Sea. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean, after the Italian islands of Sicily and Sardinia, and the 80th largest island in the world by area. It is located south of th ...

the following year. He was transferred to the ironclad on 25 July 1879 and then to the corvette on the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 18 ...

on 24 August 1880. Promoted to acting sub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second high ...

on 21 December 1881, Cradock returned to England on 6 March 1882 to prepare for his lieutenant's exams which he passed a year later. His rank confirmed, he then passed gunnery and torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

courses later in 1883.

Cradock was assigned to the ironclad in the Mediterranean after completing his courses and in 1884 was assigned to the naval brigade which had been formed for service during the Mahdist War

The Mahdist War ( ar, الثورة المهدية, ath-Thawra al-Mahdiyya; 1881–1899) was a war between the Mahdist Sudanese of the religious leader Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah, who had proclaimed himself the "Mahdi" of Islam (the "Guided On ...

. After serving in a support role during the war, he returned to his ship where he was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

on 30 June 1885. Cradock was then appointed to the gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-steam ...

as her first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

and remained there until he was placed on half-pay Half-pay (h.p.) was a term used in the British Army and Royal Navy of the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries to refer to the pay or allowance an officer received when in retirement or not in actual service.

Past usage United Kingdom

In the En ...

on 9 May 1889. He was briefly recalled to active duty aboard the new battleship to help during her shakedown cruise

Shakedown cruise is a nautical term in which the performance of a ship is tested. Generally, shakedown cruises are performed before a ship enters service or after major changes such as a crew change, repair or overhaul. The shakedown cruise s ...

and to prepare her for the fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

in Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

in August. Cradock then spent a year on the corvette , assigned to the Training Squadron. During this time, he published his first book, ''Sporting Notes from the East'', about the shooting of game

A game is a structured form of play (activity), play, usually undertaken for enjoyment, entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an educational tool. Many games are also considered to be work (such as professional players of spectator s ...

.

On 6 September 1890, Cradock was appointed first lieutenant of the sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

which arrived in the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

shortly afterwards. The Mahdist War had flared up again and the British formed the Eastern Sudan Field Force around the garrison at Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

, on Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

's Red Sea coast. Cradock was assigned to the force in 1891 and participated in the capture of Tokar. He then became aide-de-camp to Colonel Charles Holled Smith, Governor-General of the Red Sea Littoral and Commandant, Suakin. For his service in this campaign, he was awarded the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's Order of the Medjidie

Order of the Medjidie ( ota, نشانِ مجیدی, August 29, 1852 – 1922) is a military and civilian order of the Ottoman Empire. The Order was instituted in 1851 by Sultan Abdulmejid I.

History

Instituted in 1851, the Order was awarded in f ...

, 4th Class and the Khedive's Star

The Khedive's Star was a campaign medal established by Khedive Tewfik Pasha to reward those who had participated in the military campaigns in Egypt and the Sudan between 1882 and 1891. This included British forces who served during the 1882 Anglo- ...

with the Tokar Clasp. After returning to ''Dolphin'', Cradock helped to rescue the crew of the , which was wrecked on the coast of the Red Sea near Ras Zeith on 21 May 1893 during an around-the-world cadet cruise.

After a brief time on half-pay and another gunnery course, Cradock was appointed to the royal yacht

A royal yacht is a ship used by a monarch or a royal family. If the monarch is an emperor the proper term is imperial yacht. Most of them are financed by the government of the country of which the monarch is head. The royal yacht is most often c ...

on 31 August 1894 and published his second book, ''Wrinkles in Seamanship, or, Help to a Salt Horse''. He served as a pallbearer

A pallbearer is one of several participants who help carry the casket at a funeral. They may wear white gloves in order to prevent damaging the casket and to show respect to the deceased person.

Some traditions distinguish between the roles of ...

at the funeral of Prince Henry of Battenberg

Prince Henry of Battenberg (Henry Maurice; 5 October 1858 – 20 January 1896) was a morganatic descendant of the Grand Ducal House of Hesse. He became a member of the British royal family by marriage to Princess Beatrice of the United Kingdom ...

on 5 February 1896. Promoted to commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countries this naval rank is termed frigate captain.

...

on 31 August, he became the second-in-command

Second-in-command (2i/c or 2IC) is a title denoting that the holder of the title is the second-highest authority within a certain organisation.

Usage

In the British Army or Royal Marines, the second-in-command is the deputy commander of a unit, ...

of HMS ''Britannia''. Before the beginning of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

in October 1899, Cradock was briefly transferred to the drill ship to serve as a transport officer, supervising the loading of troops and supplies for South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

, and was reduced to half-pay before the end of the year.

Command and flag rank

On 1 February 1900 he was appointed in command of the third-classcruiser

A cruiser is a type of warship. Modern cruisers are generally the largest ships in a fleet after aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships, and can usually perform several roles.

The term "cruiser", which has been in use for several hu ...

, which was posted ater that year to the China Station during the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

. He commanded a mixture of British, German and Japanese sailors during the capture of the Taku forts on 17 June, led a contingent of British and Italian sailors into the Tientsin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

on 23 June, and then led the naval brigade that relieved Vice-Admiral Edward Seymour's troops besieged in the Pei-yang Arsenal three days later. Cradock was promoted to captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

effective 18 April 1901 and also received the Prussian Order of the Crown, 2nd Class with swords as a result of his actions. ''Alacrity'' arrived back in Britain on 32 July 1901 and Cradock was placed on half-pay.

On 24 March 1902 he was posted to the protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of naval cruiser of the late-19th century, gained their description because an armoured deck offered protection for vital machine-spaces from fragments caused by shells exploding above them. Protected cruisers re ...

on the Mediterranean Station, where from June that year he served as flag captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a "captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "First ...

to Rear-Admiral Sir Baldwin Wake Walker, who commanded the fleet's cruiser squadron. Cradock was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Bath

Companion may refer to:

Relationships Currently

* Any of several interpersonal relationships such as friend or acquaintance

* A domestic partner, akin to a spouse

* Sober companion, an addiction treatment coach

* Companion (caregiving), a caregive ...

on 26 June. He assumed command of the armoured cruiser on 19 December and Wake Walker shifted his flag to the ship the following day. When King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

visited Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on 2 June 1903, he appointed Cradock a Member of the Royal Victorian Order

The Royal Victorian Order (french: Ordre royal de Victoria) is a dynastic order of knighthood established in 1896 by Queen Victoria. It recognises distinguished personal service to the British monarch, Canadian monarch, Australian monarch, o ...

. Off the coast of Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label=Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after ...

, Cradock saved Prince Vudhijaya Chalermlabha

Admiral Prince Vudhijaya Chalermlabh, Prince of Singha (5 December 1883 – 18 October, 1947) was a member of Chakri Dynasty. He served as Minister of Defence and commander of Royal Thai Army between 1931 and 1932. Before then he served as th ...

, then serving as a midshipman in the Royal Navy, from drowning in April 1904. After the Dogger Bank Incident

The Dogger Bank incident (also known as the North Sea Incident, the Russian Outrage or the Incident of Hull) occurred on the night of 21/22 October 1904, when the Baltic Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy mistook a British trawler fleet from ...

, Wake Walker commanded the cruisers, including ''Bacchante'', shadowing the Russian Baltic Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Baltic fleet.svg

, image_size = 150

, caption = Baltic Fleet Great ensign

, dates = 18 May 1703 – present

, country =

, allegiance = (1703–1721) (1721–1917) (1917–1922) (1922–1991)(1991–present)

...

as it steamed through the Mediterranean in October en route to the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

. On 17 January 1905, Cradock assumed command of the armoured cruiser , but was invalided home on 17 June. He was on sick leave until September and was then placed on half-pay.

Cradock became captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the battleship on 17 July 1906 and was relieved on 6 August 1908, publishing his last book, ''Whispers from the Fleet'', in 1907. During this time the Royal Navy was riven by the feud between the reforming First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed ...

, Admiral Jackie Fisher and the traditionalist Admiral Charles Beresford and their followers. While Cradock's position on the issues dividing the navy are not positively known, a passage from ''Whispers from the Fleet'' may offer a clue: "... we require – and quickly too – some strong Imperial body of men who will straightway choke the irrepressible utterings of a certain class of individuals who, to their shame, are endeavouring to break down the complete loyalty and good comradeship that now exists in the service between the officers and the men; and who are also willing to commit the heinous crime of trifling with the sacred laws of naval discipline". After leaving command, he was again put on half-pay. He was appointed Naval Aide-de-Camp to Edward VII in February 1909 although he remained on half-pay. On 1 July Cradock was appointed in command of the Royal Naval Barracks, Portsmouth and promoted to Commodore second class while retaining his duties as aide-de-camp. Edward VII died on 6 May 1910 and Cradock stayed on until the end of October to assist his newly crowned son, King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

.

In the meantime he had been promoted to rear-admiral on 24 August 1910, and was relieved of his command in October. Still on half-pay Cradock reported to the Royal Hospital Haslar on 24 February 1911 with kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood ...

troubles and discharged himself on 7 March to attend a staff course at the Royal Naval War College at Portsmouth that lasted until 23 June. He came in sixth out of seven students, and was noted as "very attentive, but sick 1/3 of the term". On the 24th Cradock escorted visitors aboard a merchant ship to the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead. He became second-in-command of the Atlantic Fleet on 29 August, hoisting his flag aboard the predreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built between the mid- to late- 1880s and 1905, before the launch of in 1906. The pre-dreadnought ships replaced the ironclad battleships of the 1870s and 1880s. Built from steel, prot ...

. When the ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

ran aground during the night of 12/13 December near Cape Spartel

Cape Spartel ( ar, رأس سبارطيل; french: Cap Spartel; ary, أشبرتال) is a promontory in Morocco about above sea level at the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, 12 km West of Tangier. Below the cape are the Caves of Hercules. ...

, Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, smashing all of her lifeboat

Lifeboat may refer to:

Rescue vessels

* Lifeboat (shipboard), a small craft aboard a ship to allow for emergency escape

* Lifeboat (rescue), a boat designed for sea rescues

* Airborne lifeboat, an air-dropped boat used to save downed airmen

...

s, Cradock was ordered to take ''London'' and the armoured cruiser to rescue the survivors in heavy seas. It took five days to get all of the passengers and crewmen off the ship, including Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife, his wife, the Princess Royal

Princess Royal is a substantive title, style customarily (but not automatically) awarded by a United Kingdom, British monarch to their eldest daughter. Although purely honorary, it is the highest honour that may be given to a female member of th ...

, and the king's granddaughters. In recognition of his efforts, he was appointed a Knight Commander of the Royal Victorian Order on 28 February 1912 and later awarded the Sea Gallantry Medal

The Sea Gallantry Medal (SGM) (officially the 'Medal for Saving Life at Sea', and originally the ' Board of Trade Medal for Saving Life at Sea'), is a United Kingdom award for civil gallantry at sea.

History

The Merchant Shipping Act 1854 pro ...

.

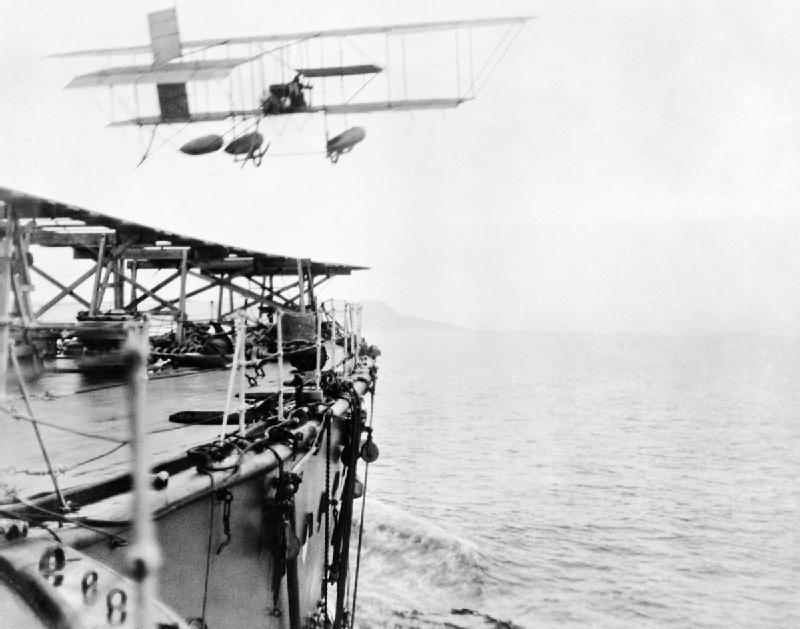

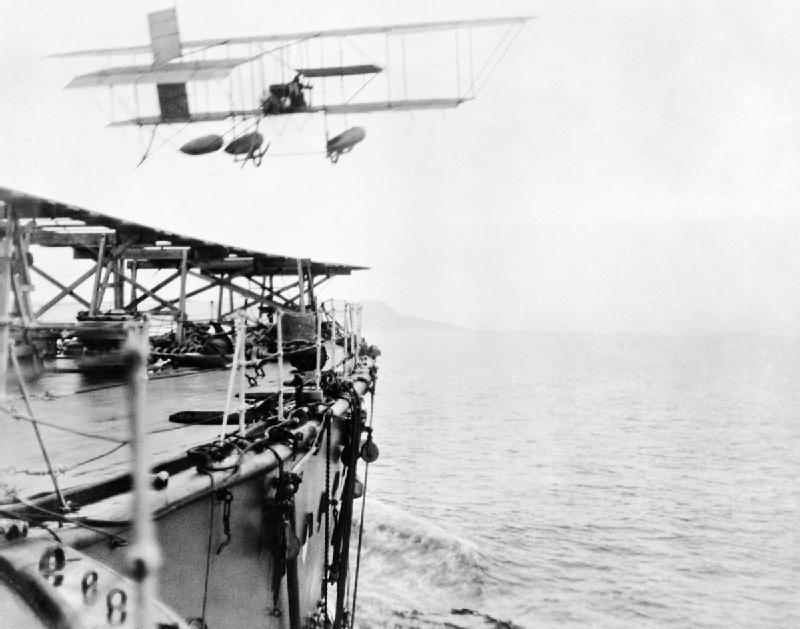

In May Cradock shifted his flag to the predreadnought battleship where he took charge of experiments that the RN was conducting with launching aircraft from ships. Commander

In May Cradock shifted his flag to the predreadnought battleship where he took charge of experiments that the RN was conducting with launching aircraft from ships. Commander Charles Samson

Air Commodore Charles Rumney Samson, (8 July 1883 – 5 February 1931) was a British naval aviation pioneer. He was one of the first four officers selected for pilot training by the Royal Navy and was the first person to fly an aircraft fr ...

had already flown off from ''Hibernia''s sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They often share a ...

while anchored earlier and she transferred her flying-off equipment to ''Hibernia'', including a runway constructed over her forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " be ...

above her forward 12-inch turret that stretched from her bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

to her bows. Samson took off from ''Hibernia'' in his Short Improved S.27

The Short S.27 and its derivative, the Short Improved S.27 (sometimes called the Short-Sommer biplane), were a series of early British aircraft built by Short Brothers. They were used by the Admiralty and Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps fo ...

biplane

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While ...

while the ship steamed at in front of George V at the Royal Fleet Review in Weymouth Bay

Weymouth Bay is a sheltered bay on the south coast of England, in Dorset. It is protected from erosion by Chesil Beach and the Isle of Portland, and includes several beaches, notably Weymouth Beach, a gently curving arc of golden sand which st ...

on 9 May, the first person to take off from a moving ship. Cradock hauled down his flag on 29 August and went on half-pay.

On 8 February 1913, he was given command of the 4th Cruiser Squadron, formerly the North America and West Indies Station

The North America and West Indies Station was a formation or command of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy stationed in North American waters from 1745 to 1956. The North American Station was separate from the Jamaica Station until 1830 when the t ...

(the main base remaining the Royal Naval Dockyard and the Admiralty House at the North Atlantic Imperial fortress

Imperial fortress was the designation given in the British Empire to four colonies that were located in strategic positions from each of which Royal Navy squadrons could control the surrounding regions and, between them, much of the planet.

His ...

colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

of Bermuda

)

, anthem = "God Save the King"

, song_type = National song

, song = " Hail to Bermuda"

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, mapsize2 =

, map_caption2 =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name =

, e ...

, and hoisted his flag in the armoured cruisers then . His orders from the Admiralty were to protect British lives and property during the ongoing Mexican Revolution, but to avoid any action that could be construed as British interference in internal Mexican affairs. The British Minister to Mexico, Sir Lionel Carden strongly disagreed with the official policy and argued for some sort of intervention. The situation was further confused by American suspicion of British actions, believing that the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile ac ...

meant that the Americans alone could intervene in Mexico.

Together with the American Rear Admiral Frank Friday Fletcher

Frank Friday Fletcher (November 23, 1855 – November 28, 1928) was a United States Navy admiral who served in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was awarded the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions ...

, Cradock coordinated the evacuation of British and American citizens from Tampico

Tampico is a city and port in the southeastern part of the state of Tamaulipas, Mexico. It is located on the north bank of the Pánuco River, about inland from the Gulf of Mexico, and directly north of the state of Veracruz. Tampico is the fifth ...

, Mexico, when that city was threatened by rebels. He then transferred his flag to on 18 February 1914 and sailed to Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a coastal resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a population of 47,743 in 2010, is the county seat of surrounding Galvesto ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, where he arrived at the end of the month. There he visited some of the refugees and was feted by the Americans, including a visit with the Governor of Texas

The governor of Texas heads the state government of Texas. The governor is the leader of the executive and legislative branch of the state government and is the commander in chief of the Texas Military. The current governor is Greg Abbott, who ...

, Oscar Colquitt before returning to Mexican waters. Cradock was in Tampico, when the Mexican Army briefly arrested nine American sailors who were purchasing petrol in the city on 9 April. Rear Admiral Henry T. Mayo, commander of the American forces off-shore, demanded an apology, but the Mexican government refused. The incident contributed to the American decision to occupy Veracruz on 21 April. Cradock was able to evacuate some 1,500 refugees from Tampico, Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

and Veracruz without incident.

First World War

When the preliminary warning for war with Imperial Germany reached Cradock on 27 July, there were two German

When the preliminary warning for war with Imperial Germany reached Cradock on 27 July, there were two German light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s in his area as the brand-new was in the process of . Cradock dispersed his cruisers to search and track the German ships, but the Admiralty was concerned about the presence of numerous ocean liners in New York that it deemed capable of being converted into armed merchant cruisers and ordered him to concentrate three of his cruisers off New York harbour. He was able to order a pair of his ships northwards and followed them in ''Suffolk'' before the declaration of war on 4 August.

On the morning of 6 August, ''Suffolk'' spotted ''Karlsruhe'' in the process of transferring guns and equipment to the liner about north of Watling Island

San Salvador Island (known as Watling's Island from the 1680s until 1925) is an island and district of The Bahamas. It is widely believed that during Christopher Columbus's first expedition to the New World, this island was the first land he s ...

. The two ships quickly departed in different directions; ''Suffolk'' followed ''Karlsruhe'' and Craddock ordered the light cruiser to intercept her. ''Karlsruhe''s faster speed allowed her to quickly outpace ''Suffolk'', but ''Bristol'' caught her that evening and fruitlessly fired at her before the German ship disengaged in the darkness. Craddock had anticipated her manoeuvres and continued eastwards, but ''Karlsruhe'' was almost out of coal and had slowed down to her most economical speed and passed behind ''Suffolk'' the following morning without being spotted before putting into Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

with only of coal remaining.

Cradock continued northward in obedience to his orders and, after rendezvousing with the newly arrived armoured cruiser at the old Royal Naval Dockyard (which had closed in 1905 and transferred to the Dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

government to become Her Majesty's Canadian Dockyard) in the former Imperial fortress

Imperial fortress was the designation given in the British Empire to four colonies that were located in strategic positions from each of which Royal Navy squadrons could control the surrounding regions and, between them, much of the planet.

His ...

of Halifax, in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, transferred his flag to her because she was faster than ''Suffolk''. ''Dresden'' was under orders to rendezvous with the East Asia Squadron in the Pacific and ''Karlsruhe'' to intercept Allied merchantmen off the north-eastern coast of Brazil, so the reported losses of shipping showed both ships moving south. In response, the Admiralty ordered Cradock southward on 22 August and appointed him in command of the South American Station the following month whilst reinforcing him with the elderly and slow predreadnought battleship . ''Good Hope'' was coaled at the Royal Naval Dockyard in Bermuda (by Bermuda Militia Artillery

The Bermuda Militia Artillery was a unit of part-time soldiers organised in 1895 as a reserve for the Royal Garrison Artillery detachment of the Regular Army garrison in Bermuda. Militia Artillery units of the United Kingdom and Colonies were in ...

gunners assisting with coaling).

On 14 September, Cradock received new orders from the Admiralty: he was apprised that the East Asia Squadron was probably heading for either the west coast of South America or the Strait of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and Tierra del Fuego to the south. The strait is considered the most important natural pass ...

and that he was to detach sufficient force to deal with ''Dresden'' and ''Karlsruhe'' while concentrating his remaining ships to meet the Germans, using the Falkland Islands to re-coal. To achieve this aim, he was to be reinforced by the modern armoured cruiser arriving from the Mediterranean. Until she arrived Cradock was to keep ''Canopus'' and one with his flagship, ''Good Hope''. Once he had superior force, he was to search for and destroy the German cruisers and break up German trade on the west coast whilst being prepared to fall back and cover the River Plate area.

The day that the Admiralty issued its order, the East Asia Squadron appeared at occupied German Samoa. Its apparent movement to the west, and the continuing depredations of the light cruiser in the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line between ...

, caused the Admiralty to conclude that Vice-Admiral Graf

(feminine: ) is a historical title of the German nobility, usually translated as "count". Considered to be intermediate among noble ranks, the title is often treated as equivalent to the British title of "earl" (whose female version is "coun ...

Maximilian von Spee

Maximilian Johannes Maria Hubert Reichsgraf von Spee (22 June 1861 – 8 December 1914) was a naval officer of the German ''Kaiserliche Marine'' (Imperial Navy), who commanded the East Asia Squadron during World War I. Spee entered the navy in ...

, commander of the East Asia Squadron, meant to rendezvous with ''Emden'' in the south western Pacific and cancelled the transfer of ''Defence'' to Cradock's command. Two days later the Admiralty messaged Cradock that von Spee was moving away from South America and that he should search the south western coast of South America for German ships without worrying about keeping his ships concentrated, but failed to inform him that ''Defence'' would not now be sent to him.

By late September, it had become clear that ''Dresden'' had passed into the Pacific Ocean and Cradock's ships fruitlessly searched several different anchorages in the area of Tierra del Fuego

Tierra del Fuego (, ; Spanish for "Land of the Fire", rarely also Fireland in English) is an archipelago off the southernmost tip of the South American mainland, across the Strait of Magellan. The archipelago consists of the main island, Isla G ...

before having to return to Port Stanley

Stanley (; also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a popula ...

in the Falklands to re-coal on 3 October. Based on intercepted radio signals, the Admiralty advised him two days later that the East Asia Squadron was probably headed his way, although he did not receive the message until 7 October.

The Hunt for the East Asia Squadron

By late October Cradock had reliable intelligence that the East Asia Squadron had reached the western coast of South America. Cradock's fleet was significantly weaker than Spee's, mainly consisting of elderly vessels manned by largely inexperienced crews. However, the orders he received from the Admiralty were ambiguous; although they were meant to make him concentrate his ships on the old battleship ''Canopus'', Cradock interpreted them as instructing him to seek and engage the enemy forces. Clarifying instructions from the Admiralty were not issued until 3 November, by which time the battle had already been fought.Battle of Coronel

Cradock found Spee's force off

Cradock found Spee's force off Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

in the late afternoon of 1 November, and decided to engage, starting the Battle of Coronel

The Battle of Coronel was a First World War Imperial German Navy victory over the Royal Navy on 1 November 1914, off the coast of central Chile near the city of Coronel. The East Asia Squadron (''Ostasiengeschwader'' or ''Kreuzergeschwader'') ...

. Useless for anything other than searching, he sent the armed merchant cruiser ''Otranto'' away. He tried to close the range immediately to engage with his shorter-ranged six-inch guns and so that the enemy would have the setting sun in their eyes, but von Spee kept the range open until dusk, when the British cruisers were silhouetted in the afterglow, while his ships were hidden by darkness. Heavily disadvantaged because the high seas had rendered the main-deck six-inch guns on ''Good Hope'' and unusable, and with partially trained crews, Cradock's two armoured cruisers were destroyed with the loss of all 1,660 lives, including his own; the light cruiser managed to escape. This battle was the first defeat of the Royal Navy in a naval action in more than a hundred years.

Departing from Port Stanley he had left behind a letter to be forwarded to Admiral Hedworth Meux

Admiral of the Fleet The Honourable Sir Hedworth Meux (pronounced ''Mews''; ''né'' Lambton; 5 July 1856 – 20 September 1929) was a Royal Navy officer. As a junior officer he was present at the bombardment of Alexandria during the Anglo-Egypt ...

in the event of his death. In this he commented that he did not intend to suffer the fate of Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge

Admiral Sir Ernest Charles Thomas Troubridge, (15 July 1862 – 28 January 1926) was an officer of the Royal Navy who served during the First World War.

Troubridge was born into a family with substantial military connections, with several of hi ...

, who had been court-martialled in August for failing to engage the enemy despite the odds being severely against him, during the pursuit of the German warships ''Goeben'' and ''Breslau''. The Governor of the Falklands and the Governor's aide both reported that Cradock had not expected to survive.

A monument to Cradock, sculpted by F. W. Pomeroy

Frederick William Pomeroy (9 October 1856 – 26 May 1924) was a prolific British sculptor of architectural and monumental works. He became a leading sculptor in the New Sculpture movement, a group distinguished by a stylistic turn towards Natu ...

, was placed in York Minster

The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, commonly known as York Minster, is the cathedral of York, North Yorkshire, England, and is one of the largest of its kind in Northern Europe. The minster is the seat of the Archbis ...

on 16 June 1916. It is on the east side of the North Transept towards the Chapter House entrance. There is another monument to Cradock in Catherington

Catherington is a village in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. It is 1 mile (1.8 km) northwest of Horndean. The village is also close to Cowplain and Clanfield. It is situated about 10 miles north of Portsmouth and eight mi ...

churchyard, Hampshire. There is a monument and a stained glass window in Cradock's memory in his parish church at Gilling West

Gilling West is a village about north of Richmond, North Yorkshire, Richmond in the Richmondshire district of North Yorkshire, England. It is located in the List of civil parishes in North Yorkshire, civil parish of Gilling with Hartforth and ...

. Having no known grave, he is commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an intergovernmental organisation of six independent member states whose principal function is to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations mil ...

on Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

Personal life

Cradock never married, but kept a dog which accompanied him at sea. He commented that he would choose to die either during an accident while hunting (his favourite pastime), or during action at sea.Massie, pp. 218–219References

Bibliography

* * * * *Further reading

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Cradock, Christopher 1862 births 1914 deaths Captains who went down with the ship Royal Navy admirals of World War I Knights Commander of the Royal Victorian Order Companions of the Order of the Bath British military personnel killed in World War I Royal Navy personnel of the Boxer Rebellion People from Richmond, North Yorkshire 19th-century British writers 20th-century British writers Recipients of the Sea Gallantry Medal