Christian Rakovsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian Georgievich Rakovsky (russian: Христиа́н Гео́ргиевич Рако́вский; bg, Кръстьо Георги́ев Рако́вски; – September 11, 1941) was a

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

n-born socialist revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

, a Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

politician and Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

diplomat and statesman; he was also noted as a journalist, physician, and essayist. Rakovsky's political career took him throughout the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and into France and Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

; for part of his life, he was also a Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n citizen.

A lifelong collaborator of Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, he was a prominent activist of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

, involved in politics with the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party

The Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party ( bg, Българска работническа социалдемократическа партия, translit=Bŭlgarska rabotnicheska sotsialdemokraticheska partiya; BRSDP) was a Bulgarian leftis ...

, Romanian Social Democratic Party, and the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

. Rakovsky was expelled at different times from various countries as a result of his activities, and, during World War I, became a founding member of the Revolutionary Balkan Social Democratic Labor Federation while helping to organize the Zimmerwald Conference. Imprisoned by Romanian authorities, he made his way to Russia, where he joined the Bolshevik Party after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

, and, as head of the '' Rumcherod'', unsuccessfully attempted to generate a communist revolution in the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

. Subsequently, he was a founding member of the Comintern

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by ...

, served as head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, a ...

in the Ukrainian SSR

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic ( uk, Украї́нська Радя́нська Соціалісти́чна Респу́бліка, ; russian: Украи́нская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респ ...

, and took part in negotiations at the Genoa Conference.

He came to oppose Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

and rallied with the Left Opposition, being marginalized inside the government and sent as Soviet ambassador to London and Paris, where he was involved in renegotiating financial settlements. He was ultimately recalled from France in autumn 1927, after signing his name to a controversial Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

platform which endorsed world revolution. Credited with having developed the Trotskyist critique of Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the the ...

as "bureaucratic centrism", Rakovsky was subject to internal exile. Submitting to Stalin's leadership in 1934 and being briefly reinstated, he was nonetheless implicated in the Trial of the Twenty One

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribunal, ...

(part of the Moscow Trials

The Moscow trials were a series of show trials held by the Soviet Union between 1936 and 1938 at the instigation of Joseph Stalin. They were nominally directed against " Trotskyists" and members of " Right Opposition" of the Communist Party o ...

), imprisoned, and executed by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

during World War II. He was rehabilitated in 1988, during the Soviet ''Glasnost

''Glasnost'' (; russian: link=no, гласность, ) has several general and specific meanings – a policy of maximum openness in the activities of state institutions and freedom of information, the inadmissibility of hushing up problems, ...

'' period.

Names

Rakovsky's original Bulgarian name was Krastyo Georgiev Stanchev (Кръстьо Георгиев Станчев), which he himself changed to ''Krastyo Rakovski'' (Кръстьо Раковски), being a descendant of the Bulgarian national hero Georgi Rakovski. The usual form his first name took inRomanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

** Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditiona ...

was ''Cristian'' (occasionally rendered as ''Christian''), while his last name was spelled ''Racovski'', ''Racovschi'', or ''Rakovski''. His given name was occasionally rendered as ''Ristache'', an antiquated hypocoristic—he was known as such to his acquaintance, writer Ion Luca Caragiale.Cioculescu, pp. 28, 46, 246–248

In Russian, his full name, including patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor.

Patronymics are still in use, including mandatory use, in many countries worldwide, alt ...

, was ''Khristian Georgievich Rakovsky'' (Христиан Георгиевич Раковский). ''Christian'' (as well as ''Cristian'' and ''Kristian'') is an approximate rendition of ''Krastyo'' (the Bulgarian for "cross"), as used by Rakovsky himself.Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans'' In Ukrainian

Ukrainian may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Ukraine

* Something relating to Ukrainians, an East Slavic people from Eastern Europe

* Something relating to demographics of Ukraine in terms of demography and population of Ukraine

* So ...

, Rakovsky's name is rendered as Християн Георгійович Раковський, and usually transliterated

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus ''trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → , Cyrillic → , Greek → the digraph , Armenian → or L ...

as ''Khrystyian Heorhiiovych Rakovskyi''.

During his lifetime, he was also known under the pseudonyms ''H. Insarov'' and ''Grigoriev'', which he used in signing several articles for the Russian-language press.

Biography

Revolutionary beginnings

Christian Rakovsky was born to a wealthy Bulgarian family in Gradets — near Kotel — at the time still part of Ottoman-ruledRumelia

Rumelia ( ota, روم ايلى, Rum İli; tr, Rumeli; el, Ρωμυλία), etymologically "Land of the Romans", at the time meaning Eastern Orthodox Christians and more specifically Christians from the Byzantine rite, was the name of a hi ...

. He was, on his mother's side, the nephew of Georgi Sava Rakovski, a revolutionary hero of the Bulgarian National Revival;Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography"; Upson Clark that side of his family also included Georgi Mamarchev, who had fought against the Ottomans in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

.Rakovsky, "An Autobiography" Rakovsky's father was a merchant who belonged to the Democratic Party.

He later stated that, as early as his childhood years, he had felt a special admiration towards Russia, and that he had been impressed by witnessing, at age 5, the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

and Russian presence (he claimed to have met General Eduard Totleben during the conflict).

Although his parents moved to the Kingdom of Romania

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

in 1880, settling in Gherengic (Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( ro, Dobrogea de Nord or simply ; bg, Северна Добруджа, ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube river and the Black Sea, bordered in the south ...

), he completed his education in newly emancipated Bulgaria.Rakovsky, ''An Autobiography''; Upson Clark. Rakovsky was expelled from the gymnasium in Gabrovo

Gabrovo ( bg, Габрово ) is a town in central northern Bulgaria, the administrative centre of Gabrovo Province.

It is situated at the foot of the central Balkan Mountains, in the valley of the Yantra River, and is known as an internat ...

for his political activities (in 1887 and then again, after organizing a riot, in 1890). It was around that time that he became a Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

, and began collaborating with the socialist journalist Evtim Dabev, whom he aided in printing works by Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography". Since, after having ultimately been banned from attending any public school in the country, he could not complete his education in Bulgaria, in September 1890, Rakovsky went to

'' Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Rakovsky, "An Autobiography". Since, after having ultimately been banned from attending any public school in the country, he could not complete his education in Bulgaria, in September 1890, Rakovsky went to

Geneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaking part of Switzerland. Situa ...

to begin his studies and become a physician. While in Switzerland, he joined the Socialist Student Circle at the University of Geneva

The University of Geneva (French: ''Université de Genève'') is a public research university located in Geneva, Switzerland. It was founded in 1559 by John Calvin as a theological seminary. It remained focused on theology until the 17th centur ...

, which was largely composed of non-Swiss youth.

A polyglot

Multilingualism is the use of more than one language, either by an individual speaker or by a group of speakers. It is believed that multilingual speakers outnumber monolingual speakers in the world's population. More than half of all Eu ...

,Anghel & Iosif, pg. 257; Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''. Rakovsky became close to Georgy Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (; rus, Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revoluti ...

, the founder of Russian Marxism, and his circle, eventually writing a number of articles and a book in Russian. He briefly worked with Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialism, revolutionary socialist, Marxism, Marxist philosopher and anti-war movement, anti-war activist. Succ ...

, Pavel Axelrod

Pavel Borisovich Axelrod (russian: Па́вел Бори́сович Аксельро́д; 25 August 1850 – 16 April 1928) was an early Russian Marxist revolutionary. Along with Georgi Plekhanov, Vera Zasulich, and Leo Deutsch, he was one ...

, and Vera Zasulich

Vera Ivanovna Zasulich (russian: link=no, Ве́ра Ива́новна Засу́лич; – 8 May 1919) was a Russian socialist activist, Menshevik writer and revolutionary.

Radical beginnings

Zasulich was born in Mikhaylovka, in the Smol ...

. Unable to attend the First International Congress of Socialist Students in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

(1892), he became involved in organizing the Second Congress, held in Geneva during the fall of 1893.

He was a founding editor of the Geneva-based Bulgarian-language magazine ''Sotsial-Demokrat'' and later a major contributor to the Bulgarian Marxist publications ''Den, ''Rabotnik'', and ''Drugar''. At the time, Rakovsky and Balabanov, with Plekhanov's encouragement, stressed the importance for moderation in socialist policies—''Sotsial-Demokrat'' rallied with the Bulgarian Social Democratic Union

The Bulgarian Social Democratic Union ( bg, Български социалдемократически съюз) was a Bulgarian leftist group founded in 1892.

History

In 1892 a group, led by Yanko Sakazov, founded a reformist organization, the ...

and rejected the more radical Bulgarian Social Democratic Party

The Bulgarian Social Democratic Party ( bg, Българска социалдемократическа партия, ''Balgarska Sotsialdemokraticheska Partiya'', BSDP) is a social democratic political party in Bulgaria.

It was part of the Blue ...

. He soon became involved in distributing socialist propaganda inside Bulgaria, at a time when Stefan Stambolov organized a crackdown on political opposition.

Later in 1893, Rakovsky enrolled in a medical school in Berlin, contributing articles for ''Vorwärts

''Vorwärts'' (, "Forward") is a newspaper published by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Founded in 1876, it was the central organ of the SPD for many decades. Following the party's Halle Congress (1891), it was published daily as ...

'' and becoming close to Wilhelm Liebknecht

Wilhelm Martin Philipp Christian Ludwig Liebknecht (; 29 March 1826 – 7 August 1900) was a German socialist and one of the principal founders of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). As a Bulgarian delegate to the

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the  Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the

In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the

''Russia in 1919''

Retrieved 19 July 2007. While in office, Rakovsky totally ignored Ukrainian issues, considering Ukraine and its language merely "an invention" of intellectuals.Fagan, ''Rakovsky and the Ukraine (1919–23)''. At the time, Rakovsky assessed the situation created by the Rakovsky simultaneously served as Soviet Ukraine's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and a member of the South West Front's Revolutionary Military Council, contributing to the defeat of the

Rakovsky simultaneously served as Soviet Ukraine's Commissar for Foreign Affairs and a member of the South West Front's Revolutionary Military Council, contributing to the defeat of the

In February 1922, he was sent to Berlin in order to negotiate with German officials, and, in March, was part of the official delegation to the Genoa Conference — under the leadership of

In February 1922, he was sent to Berlin in order to negotiate with German officials, and, in March, was part of the official delegation to the Genoa Conference — under the leadership of

In parallel, he had begun negotiations with France's

In parallel, he had begun negotiations with France's  Together with his second wife, Rakovsky gave full approval to Max Eastman's volume ''Since Lenin Died'', which centered on heavy criticism of Soviet realities, and which they reviewed before it was published. He became acquainted with the former

Together with his second wife, Rakovsky gave full approval to Max Eastman's volume ''Since Lenin Died'', which centered on heavy criticism of Soviet realities, and which they reviewed before it was published. He became acquainted with the former

After that moment, although branded "

After that moment, although branded "

РаковскийПотапенко1927.jpg, Rakovsky on the cigarettes pack, 1927, Kharkiv, U.S.S.R.

Christian Rakovsky Internet Archive

at

Biographical Introduction to Christian Rakovsky, ''Selected Writings on Opposition in the USSR 1923–30'' (editor: Gus Fagan), Allison & Busby, London & New York, 1980

retrieved July 19, 2007 ** Christian Rakovsky

translated by Gus Fagan; retrieved July 19, 2007 *

''110 ani de social-democraţie în România'' ("110 Years of Social Democracy in Romania")

''Arbitrary Justice: Courts and Politics in Post-Stalin Russia''

National Council for Soviet and East European Research and

''Les socialistes et la guerre'' ("The Socialists and the War"), 1915

at Marxists.org (French edition); retrieved July 19, 2007 * Judith Shapiro

in '' Revolutionary History'', Vol. 2, No. 2, Summer 1989; retrieved July 19, 2007 *

"Cristian Racovski" (Part I)

in ''

"The Renegade Istrati", excerpt from ''Auntie Varvara's Clients''

translated by Alistair Ian Blyth, in ''Archipelago'', Vol.10–12; retrieved July 19, 2007 * Vladimir Tismăneanu, ''Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism'',

''Christian Rakovsky et Basile Kolarov'' ("Christian Rakovsky and Vasil Kolarov"), 1915

at Marxists.org (French edition); retrieved July 19, 2007 *

''Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea'': Chapter XXI, "Rakovsky's Roumanian Career"

at the

Trotsky's unfinished biography of Rakovsky

*

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Rakovsky, Christian 1873 births 1941 deaths People from Kotel, Bulgaria Bulgarian expatriates in Ukraine Bulgarian activists Bulgarian communists Bulgarian journalists Bulgarian people of World War I Romanian activists Romanian communists Romanian escapees Romanian Land Forces officers Romanian magazine editors Romanian newspaper editors Romanian people of World War I Romanian military doctors Romanian political candidates People deported from Romania Escapees from Romanian detention Marxist journalists Social Democratic Party of Romania (1910–1918) politicians Leaders of political parties in Romania Anti–World War I activists People of the Russian Revolution Romanian Comintern people Communist Party of the Soviet Union members Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) politicians Politicians of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to France Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to the United Kingdom Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Japan Romanian Trotskyists Romanian people of Bulgarian descent Romanian writers in French Bulgarian expatriates in Romania Bulgarian Comintern people Great Purge victims Case of the Anti-Soviet "Bloc of Rightists and Trotskyites" Bulgarian people imprisoned abroad Bulgarian people executed by the Soviet Union Executed Soviet people Civilians killed in World War II Deaths by firearm in the Soviet Union Soviet rehabilitations Soviet show trials Executed Bulgarian people Anti-Ukrainian sentiment Ukrainian diplomats Chairpersons of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine Left Opposition Old Bolsheviks Soviet interior ministers of Ukraine Soviet foreign ministers of Ukraine Marxian economists Executed communists

Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

Congress in Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z ...

, he also met with Engels and Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

.

Six months later, he was arrested and expelled from the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

for maintaining close contacts with the Russian revolutionaries there. He finished his education in 1894–1896 in Zürich

, neighboring_municipalities = Adliswil, Dübendorf, Fällanden, Kilchberg, Maur, Oberengstringen, Opfikon, Regensdorf, Rümlang, Schlieren, Stallikon, Uitikon, Urdorf, Wallisellen, Zollikon

, twintowns = Kunming, San Francisco

Z ...

, Nancy and Montpellier

Montpellier (, , ; oc, Montpelhièr ) is a city in southern France near the Mediterranean Sea. One of the largest urban centres in the region of Occitania, Montpellier is the prefecture of the department of Hérault. In 2018, 290,053 people l ...

, where he wrote for '' La Jeunesse Socialiste'' and '' La Petite République'', maintaining a friendship with Guesde and becoming an opponent of Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

' reformist

Reformism is a political doctrine advocating the reform of an existing system or institution instead of its abolition and replacement.

Within the socialist movement, reformism is the view that gradual changes through existing institutions can ...

views.

According to his own testimony, he became active in supporting the Anti-Ottoman upsurge in Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, ...

and Macedonia, as well as Dashnak revolutionary activities. In 1896, he was the Bulgarian representative to the Second International's London Congress (part of his speech was published in Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels ...

's ''Die Neue Zeit

''Die Neue Zeit'' (German: "The New Times") was a German socialist theoretical journal of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) that was published from 1883 to 1923. Its headquarters was in Stuttgart, Germany.

History and profile

Founded ...

'').

Military service and first stay in Russia

Although actively involved in many European countries' socialist movements, prior to 1917 Rakovsky's focus remained on the Balkans and especially on his native country and Romania; his activities in support of the international socialist movement led to his expulsion, at different times, from Germany, Bulgaria, Romania, France and Russia. In 1897, he published ''Russiya na Istok'' (''Russia in the East''), a book sharply critical of theRussian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

's foreign policy, which, according to Rakovsky, followed one of Georgy Plekhanov

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (; rus, Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов, p=ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪj vəlʲɪnˈtʲinəvʲɪtɕ plʲɪˈxanəf, a=Ru-Georgi Plekhanov-JermyRei.ogg; – 30 May 1918) was a Russian revoluti ...

's guidelines ("Tsarist Russia must be isolated in its foreign relations"). On several occasions, he publicly criticized Russia's policies towards Romania and in Bessarabia

Bessarabia (; Gagauz: ''Besarabiya''; Romanian: ''Basarabia''; Ukrainian: ''Бессара́бія'') is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds o ...

(describing Russia's rule over the latter as " absolutist conquest", "mischievous action", and "abduction"). According to Rakovsky, "Russophile

Russophilia (literally love of Russia or Russians) is admiration and fondness of Russia (including the era of the Soviet Union and/or the Russian Empire), Russian history and Russian culture. The antonym is Russophobia. In the 19th Cen ...

papers" in Bulgaria had begun to target him as a consequence.

After completing his education as a physician at the University of Montpellier

The University of Montpellier (french: Université de Montpellier) is a public research university located in Montpellier, in south-east of France. Established in 1220, the University of Montpellier is one of the oldest universities in the wor ...

Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Tănase, "Cristian Racovski". (with the thesis ''L'Éthiologie du crime et de la dégénérescence'' – "The Cause of Crime and Degeneration", submitted in 1897),Fagan, ''Socialist leader in the Balkans''; Upson Clark Rakovsky, who had married the Russian student E. P. Ryabova, was summoned to Romania in order to be drafted in the Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

, and served as a medic

A medic is a person involved in medicine such as a medical doctor, medical student, paramedic or an emergency medical responder.

Among physicians in the UK, the term "medic" indicates someone who has followed a "medical" career path in postgra ...

in the 9th Cavalry Regiment stationed in Constanţa, Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; bg, Добруджа, Dobrudzha or ''Dobrudža''; ro, Dobrogea, or ; tr, Dobruca) is a historical region in the Balkans that has been divided since the 19th century between the territories of Bulgaria and Romania. I ...

(1899–1900). He rose to the rank of lieutenant.Upson Clark

Rakovsky subsequently rejoined his wife in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, where he hoped to settle down and engage in revolutionary activities (he was probably expelled after an initial attempt to enter the country, but was allowed to return). An adversary of Peter Berngardovich Struve after the latter moved towards market liberalism, he became acquainted with, among others, Nikolay Mikhaylovsky

Nikolay Konstantinovich Mikhaylovsky () (, Meshchovsk–, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian literary critic, sociologist, writer on public affairs, and one of the theoreticians of the Narodniki movement.

Biography

The school of thinkers he bel ...

and Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky, while authoring articles for ''Nashe Slovo

''Nashe Slovo'' ( rus, Наше Слово, Our Word) was a daily Russian language socialist newspaper published in France during the First World War. Although it only appeared for a little over a year and a half, it had an impact across Europe.

...

'' and helping distribute ''Iskra

''Iskra'' ( rus, Искра, , ''the Spark'') was a political newspaper of Russian socialist emigrants established as the official organ of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).

History

Due to political repression under Tsar Nicho ...

''. His close relationship with Plekhanov led Rakovsky to a position between the Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

and Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

, one he kept from 1903 to 1917; the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

was initially hostile to Rakovsky, and at one point wrote to Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (russian: Карл Бернгардович Радек; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and a Marxist active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a ...

that "we he Bolsheviksdo not have the same road as his kind of people".

Initially, Rakovsky was expelled from Russia and had to move back to Paris. Returning to the Russian capital in 1900, he remained there until 1902, when his wife's death and the crackdown on socialist groups ordered by Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pol ...

forced him to return to France. Working for a while as a physician in the village of Beaulieu, Haute-Loire

Beaulieu () is a commune in the Haute-Loire department and Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of south-east central France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Haute-Loire department

The following is a list of the 257 communes of the Haute- ...

, he asked French officials to review his case for naturalization

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

, but was refused.

In 1903, following the death of his father, Rakovsky again lived in Paris, where he followed developments of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

and spoke out against Russia, attracting, according to Rakovsky himself, the criticism of both Plekhanov and Jules Guesde

Jules Bazile, known as Jules Guesde (; 11 November 1845 – 28 July 1922) was a French socialist journalist and politician.

Guesde was the inspiration for a famous quotation by Karl Marx. Shortly before Marx died in 1883, he wrote a letter ...

. He voiced his opposition to the concession made by Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels ...

to Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

, one which had allowed socialists to join "bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. ...

" governments in times of crisis.Rakovsky, ''Les socialistes et la guerre''.

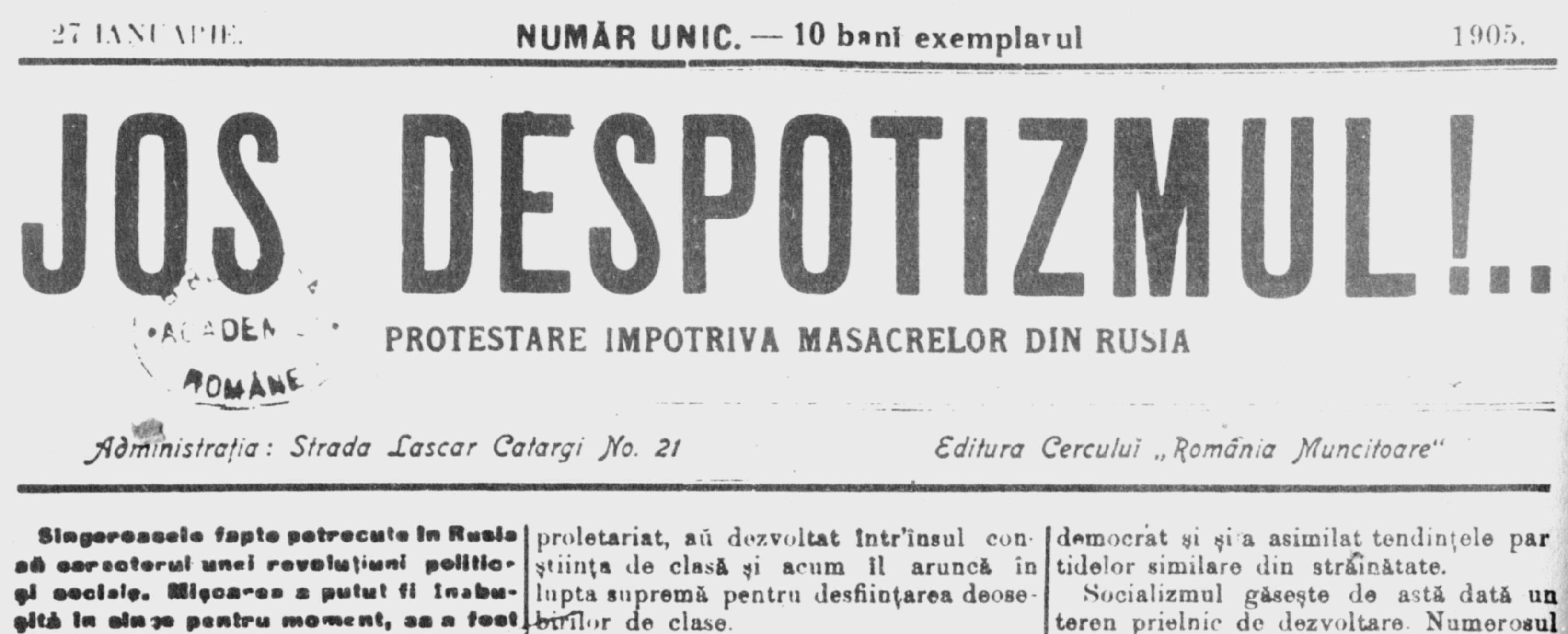

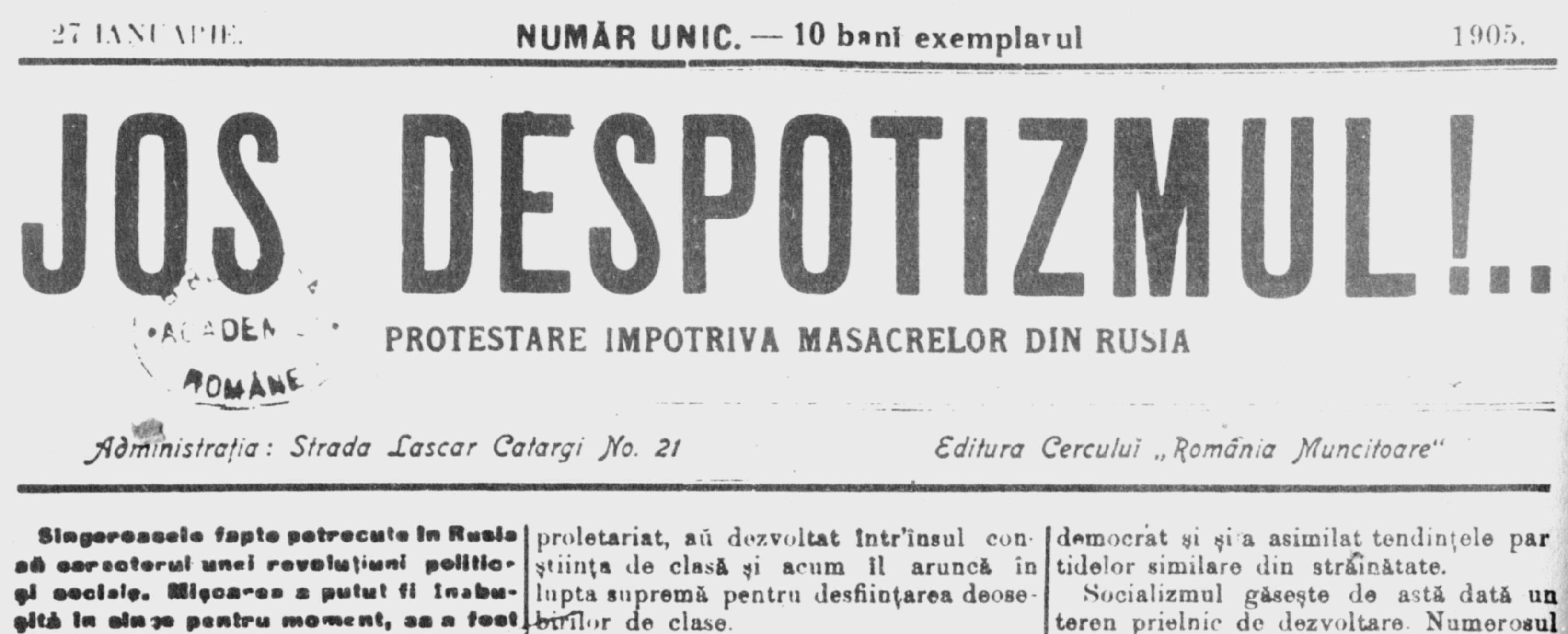

''România Muncitoare''

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near

He ultimately settled in Romania (1904) having inherited his father's estate near Mangalia

Mangalia (, tr, Mankalya), ancient Callatis ( el, Κάλλατις/Καλλατίς; other historical names: Pangalia, Panglicara, Tomisovara), is a city and a port on the coast of the Black Sea in the south-east of Constanța County, Norther ...

. In 1913, his property, valued at some 40,000 United States dollars at the time, was home to Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

when the latter visited the Balkans as a press envoy during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

. He was usually present in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

on a weekly basis, and started an intense activity as a journalist, doctor and lawyer. The Balkans correspondent for ''L'Humanité

''L'Humanité'' (; ), is a French daily newspaper. It was previously an organ of the French Communist Party, and maintains links to the party. Its slogan is "In an ideal world, ''L'Humanité'' would not exist."

History and profile

Pre-World Wa ...

'', he was also personally responsible for reviving '' România Muncitoare'', the defunct journal of the Romanian socialist group, provoking successful strike actions which brought him to the attention of officials.

Christian Rakovsky also traveled to Bulgaria, where he eventually sided with the '' Tesnyatsi'' in their conflict with other socialist groups. In 1904, he was present at the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

's Congress in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

, where he gave a speech celebrating the assassination of Russian police chief Vyacheslav von Plehve

Vyacheslav Konstantinovich von Plehve ( rus, Вячесла́в (Wenzel (Славик)) из Плевны Константи́нович фон Пле́ве, p=vʲɪtɕɪˈslaf fɐn ˈplʲevʲɪ; – ) served as a director of Imperial Russ ...

by Socialist-Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major polit ...

members.

Rakovsky became noted locally especially after 1905, when he organized rallies in support of the Battleship Potemkin revolt (the events worsened relations between Russia and the Romanian Kingdom

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romania ...

), carried out a relief operation for the ''Potemkin'' crew as their ship sought refuge in Constanţa, and attempted to persuade them to set sail for Batumi

Batumi (; ka, ბათუმი ) is the List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), second largest city of Georgia (country), Georgia and the capital of the Autonomous Republic of Adjara, located on the coast of the Black Sea in Georgia's ...

and aid striking workers there. According to his own account, a parallel scandal occurred when an armed Bolshevik ship was captured in Romanian territorial waters; Rakovsky, who indicated that the weapons on board were to be used in Batumi, faced allegations in the Romanian press that he was preparing a Dobruja

Dobruja or Dobrudja (; bg, Добруджа, Dobrudzha or ''Dobrudža''; ro, Dobrogea, or ; tr, Dobruca) is a historical region in the Balkans that has been divided since the 19th century between the territories of Bulgaria and Romania. I ...

n insurrection.

His head was injured during street clashes with police forces

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

over the ''Potemkin'' issue; while recovering, Rakovsky befriended the Romanian poets Ştefan Octavian Iosif and Dimitrie Anghel

Dimitrie Anghel (; July 16, 1872 – November 13, 1914) was a Romanian poet.

Anghel was of Aromanian descent from his father. His first poem was published in ''Contemporanul'' (1890). His debut editorial ''Traduceri din Paul Verlaine'' was publi ...

, who were publishing works under a common signature—one of the two authored a sympathetic portrait of the socialist leader, based on his recollections from the early 1900s. Throughout these years, Rakovsky, was, according to Iosif and Anghel, "continuously bustling; disappearing and appearing in workers' centers, be it in Brăila

Brăila (, also , ) is a city in Muntenia, eastern Romania, a port on the Danube and the capital of Brăila County. The Sud-Est (development region), ''Sud-Est'' Regional Development Agency is located in Brăila.

According to the 2011 Romanian ...

, be it in Galaţi, be it in Iaşi, be it anywhere, always preaching with the same undaunted fervor and fanatical conviction his social credo".

Rakovsky was drawn into a polemic with the Romanian authorities, facing public accusations that, as a Bulgarian, he lacked patriotism. In return, he commented that, if patriotism meant " race prejudice, international and civil war, political tyranny

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

and plutocratic

A plutocracy () or plutarchy is a society that is ruled or controlled by people of great wealth or income. The first known use of the term in English dates from 1631. Unlike most political systems, plutocracy is not rooted in any establish ...

domination", he refused to be identified with it. Upon the outbreak of Romanian Peasants' Revolt of 1907, Rakovsky was especially vocal: he launched accusations at the National Liberal

National liberalism is a variant of liberalism, combining liberal policies and issues with elements of nationalism. Historically, national liberalism has also been used in the same meaning as conservative liberalism (right-liberalism).

A seri ...

government, arguing that, having profited from the early antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

message of the revolt, it had violently repressed it from the moment peasants began to attack landowners. Supportive of the thesis according to which the peasantry had revolutionary importance inside Romanian society and Eastern Europe at large, Rakovsky publicized his perspective in the socialist press (writing articles on the subject for ''România Muncitoare'', ''L'Humanité'', ''Avanti!

''Avanti!'' is a 1972 American/Italian international co-production comedy film produced and directed by Billy Wilder, and starring Jack Lemmon and Juliet Mills. The screenplay by Wilder and I. A. L. Diamond is based on Samuel A. Taylor's play, ...

'', ''Vorwärts

''Vorwärts'' (, "Forward") is a newspaper published by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Founded in 1876, it was the central organ of the SPD for many decades. Following the party's Halle Congress (1891), it was published daily as ...

'' and others).

Rakovsky was also one of the journalists suspected of having greatly exaggerated the overall death toll in their accounts: his estimates speak of over 10,000 peasants killed, whereas the government data counted only 421.

He became close to the influential dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale, who was living in Berlin at the time. Caragiale authored his own virulent critique of the Romanian state and its handling of the revolt, an essay titled ''1907, din primăvară până în toamnă'' ("1907, From Spring to Autumn"), which, in its final version, adopted some of Rakovsky's suggestions.

1907 expulsion

After repeatedly condemning repression of the revolt, Rakovsky was, together with other socialists, officially accused of having agitated rebellious sentiment, and consequently expelled from Romanian soil (late 1907). He received news of this action while already abroad, inStuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the Sw ...

(at the Seventh Congress of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

). He decided not to recognize it, and contended that his father had settled in Northern Dobruja

Northern Dobruja ( ro, Dobrogea de Nord or simply ; bg, Северна Добруджа, ''Severna Dobrudzha'') is the part of Dobruja within the borders of Romania. It lies between the lower Danube river and the Black Sea, bordered in the south ...

before the Treaty of Berlin that had awarded the region to Romania; the plea was rejected by the Court of Appeal

A court of appeals, also called a court of appeal, appellate court, appeal court, court of second instance or second instance court, is any court of law that is empowered to hear an appeal of a trial court or other lower tribunal. In much ...

, based on evidence that Rakovsky's father was not in Dobruja before 1880, and that Rakovsky himself used a Bulgarian passport when moving across borders. During the 1920s, Rakovsky was still viewing the incident as a "blatantly illegal act".

The action itself caused protests from leftist politicians and sympathizers, including, among others, the influential Marxist thinker Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 1855, village of Slavyanka near Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipro), then in Imperial Russia – 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and ...

(whose appeal in favor of Rakovsky was described by Iosif and Anghel as evidence of "an almost parental love"). The local socialists organized several rallies in his support, and the return of his citizenship was also backed by Take Ionescu's opposition group, the Conservative-Democratic Party

The Conservative-Democratic Party (, PCD) was a political party in Romania. Over the years, it had the following names: the Democratic Party, the Nationalist Conservative Party, or the Unionist Conservative Party.

The Conservative-Democratic Part ...

. In exile, Rakovsky authored the pamphlet ''Les persécutions politiques en Roumanie'' ("Political Persecutions in Romania") and two books (''La Roumanie des boyars'' – "Boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

Romania", and the since-lost ''From the Kingdom of Arbitrariness and Cowardice'').

Eventually, he traveled back into Romania in October 1909, only to be arrested upon his transit through Brăila County

Brăila County () is a county (județ) of Romania, in Muntenia, with the capital city at Brăila.

Demographics

In 2011, Brăila had a population of 304,925 and the population density was 64/km2.

* Romanians – 98%

* Romani, Russians, Lipo ...

.

According to his recollections, he was for long left stranded on the border with Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, as officials in the latter country refused to let him pass; the situation had to be settled by negotiations between the two countries. Also according to Rakovsky, the arrest was hidden by the Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion Ionel Constantin Brătianu (, also known as Ionel Brătianu; 20 August 1864 – 24 November 1927) was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL), Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on se ...

cabinet until it leaked to the press — this, coupled with rumors that he was about to be killed, and Brătianu's statement that he would "rather destroy akovskythan let imback into Rumania", caused a series of important street clashes between his supporters and government forces. On 9 December 1909, a Romanian Railways

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

employee named Stoenescu attempted to assassinate Brătianu. The event, which was attributed by Rakovsky to support for his return and by other sources to government manipulation,Ornea, pp. 521-522 caused a clampdown on '' România Muncitoare'' (among those socialists arrested and interrogated were Gheorghe Cristescu, I. C. Frimu, and Dumitru Marinescu).

Rakovsky secretly returned to Romania in 1911, giving himself up in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

. According to Rakovsky, he was again expelled, holding a Romanian passport, to Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

, where he was swiftly arrested by the Young Turks government but released soon after. He subsequently left for Sofia

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and h ...

, where he established the Bulgarian socialist journal '' Napred''. Ultimately, the new Petre P. Carp Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

cabinet agreed to allow his return to Romania, following pressures from the French Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

Georges Clemenceau

Georges Benjamin Clemenceau (, also , ; 28 September 1841 – 24 November 1929) was a French statesman who served as Prime Minister of France from 1906 to 1909 and again from 1917 until 1920. A key figure of the Independent Radicals, he was a ...

(who answered an appeal by Jean Jaurès

Auguste Marie Joseph Jean Léon Jaurès (3 September 185931 July 1914), commonly referred to as Jean Jaurès (; oc, Joan Jaurés ), was a French Socialist leader. Initially a Moderate Republican, he later became one of the first social dem ...

). According to Rakovsky, this was also determined by the Conservative change in policies towards the peasantry. He unsuccessfully ran for Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries. Th ...

during the elections of that year (and several others in succession), being fully reinstated as a citizen in April 1912. Romanian journalist Stelian Tănase

Stelian Tănase (born February 17, 1952) is a Romanian writer, journalist, political analyst, and talk show host. Tănase was from November 2013 to October 2015 the president of TVR. Having briefly engaged in politics during the early 1990s, aft ...

contends that the expulsion had instilled resentment in Rakovsky;Tănase, "Cristian Racovski" earlier, the leading National Liberal politician Ion G. Duca himself had argued that Rakovsky was developing a "hatred for Romania".

PSDR and Zimmerwald Movement

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the

Alongside Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor and Frimu, Rakovsky was one of the founders of the Romanian Social Democratic Party (PSDR), serving as its president.

In May 1912, he helped organize a mourning session for the centennial of Russian rule in Bessarabia, and authored numerous new articles on the matter. He was afterwards involved in calling for peace during the Balkan Wars

The Balkan Wars refers to a series of two conflicts that took place in the Balkan States in 1912 and 1913. In the First Balkan War, the four Balkan States of Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Bulgaria declared war upon the Ottoman Empire and def ...

; notably, Rakovsky expressed criticism of Romania's invasion of Bulgaria during the Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 ( O.S.) / 29 (N.S.) June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies ...

, and called on Romanian authorities not to annex Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja, South Dobruja or Quadrilateral ( Bulgarian: Южна Добруджа, ''Yuzhna Dobrudzha'' or simply Добруджа, ''Dobrudzha''; ro, Dobrogea de Sud, or ) is an area of northeastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silis ...

. Alongside Frimu, Bujor, Ecaterina Arbore and others, he lectured at the PSDR's propaganda school during the short period the latter was in existence (in 1910 and again in 1912–1913).

In 1913, Rakovsky was married a second time, to Alexandrina Alexandrescu (also known as Ileana Pralea), a socialist militant and intellectual, who taught mathematics in Ploieşti.Brătescu, pg. 425 Alexandrescu was herself a friend of Dobrogeanu-Gherea and an acquaintance of Caragiale. She had previously been married to Filip Codreanu, a Narodnik

The Narodniks (russian: народники, ) were a politically conscious movement of the Russian intelligentsia in the 1860s and 1870s, some of whom became involved in revolutionary agitation against tsarism. Their ideology, known as Narodism, ...

activist born in Bessarabia, with whom she had a daughter, Elena, and a son, Radu.

Rallying with the left wing of international social democracy

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote s ...

during the early stages of World War I, Rakovsky later indicated that he had been purposely informed of the controversial pro-war stance taken by the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

by the pro- Entente Romanian Foreign Minister Emanoil Porumbaru

Emanoil Porumbaru (1845 – 11 October 1921) was a Romanian politician who served as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Romania from 4 January 1914 until 7 December 1916 under the reign of Romanian kings Carol I and Ferdinand, and as President o ...

.Fagan, ''Regroupment of the socialist movement'' With staff of the Menshevik paper ''Nashe Slovo

''Nashe Slovo'' ( rus, Наше Слово, Our Word) was a daily Russian language socialist newspaper published in France during the First World War. Although it only appeared for a little over a year and a half, it had an impact across Europe.

...

'' (edited by Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

), he was among the most prominent socialist pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigne ...

of the period. Reflecting his ideological priorities, '' România Muncitoares title was changed into ''Jos Răsboiul!'' ("Down with war!")—it was later to be known as ''Lupta Zilnică'' (the "Daily combat").

Heavily critical of the French Socialist Party

The Socialist Party (french: Parti socialiste , PS) is a French centre-left and social-democratic political party. It holds pro-European views.

The PS was for decades the largest party of the "French Left" and used to be one of the two major po ...

's decision to join the René Viviani cabinet (deeming it "an abdication"), he stressed the responsibility of all European countries in provoking the war, and adhered to Trotsky's vision of a "Peace without indemnities or annexations" as an alternative to "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power ( economic and ...

war". According to Rakovsky, tensions between the French SFIO and the German Social Democrats were reflecting not just context, but major ideological differences.

Present in Italy in March 1915, he attended the Milan

Milan ( , , Lombard: ; it, Milano ) is a city in northern Italy, capital of Lombardy, and the second-most populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of about 1.4 million, while its metropolitan city ...

Congress of the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 189 ...

, during which he attempted to persuade it to condemn irredentist goals.Rakovsky, "An Autobiography"; Tănase, "Cristian Racovski". In July, after convening the Bucharest Conference, he and Vasil Kolarov established the Revolutionary Balkan Social Democratic Labor Federation (comprising the left-leaning socialist parties of Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

and Greece), and Rakovsky was elected first secretary of its Central Bureau.

Subsequently, together with the Italian Socialist delegates (Oddino Morgari

Oddino Morgari (November 16, 1865 – November 24, 1944) was an Italian socialist journalist and politician. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies from 1897 to 1929, for eight legislatures.

Early life

Initially a Mazzinian radical, he ...

, Giacinto Menotti Serrati

Giacinto Menotti Serrati (25 November 1872 – 10 May 1926) was an Italian communist politician and newspaper editor.

Biography

He was born in Spotorno, near Savona and died in Asso, near Como.

Serrati was a central leader of the Italian Soc ...

, and Angelica Balabanoff among them), Rakovsky was instrumental in convening the anti-war international socialist Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915. During the congress, he came into open conflict with Lenin, after the latter voiced the Zimmerwald Left's opposition to the resolution (at one point, Rakovsky reportedly lost his temper and grabbed Lenin, causing him to temporarily leave the hall in protest). Later, he continued to mediate between Lenin and the Second International, a situation from which emerged a circular letter that complemented the ''Zimmerwald Manifesto'' while being more radical in tone. In October 1915, he reportedly did not protest Bulgaria's entry into the war — this information was contradicted by Trotsky, who also indicated that the '' Tesniatsy'' had been the target of a government crackdown at that exact moment.

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in

Rakovsky ran for Parliament for a final time during 1916, and again lost when contesting a seat in Covurlui County

Covurlui County is one of the historic counties of Moldavia, Romania. The county seat was Galați.

In 1938, the county was disestablished and incorporated into the newly formed Ținutul Dunării, but it was re-established in 1940 after the fall o ...

. Again arrested in 1916, after being accused of planning rebellion during a violent incident in Galaţi, he was, according to his own account, freed by a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coa ...

which constituted "an outburst of indignation among the workers". Evaluating the situation in Romania, he identified the two main pro-Entente political forces of the moment, the groups led by Take Ionescu and Nicolae Filipescu

Nicolae Filipescu (December 5, 1862 – September 30, 1916) was a Romanian politician.

Filipescu was the mayor of Bucharest between February 1893 and October 1895. It was during his term the first electric tramways circulated in Bucharest.

Betw ...

, with, respectively, "corruption" and "reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

* Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and m ...

".

Suspicions also rose that he had been contacted by German intelligence, that his 1915 trip to Italy had served German interests, and that he was being subsidized with German money. Rakovsky also drew attention to himself after welcoming to Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north o ...

the pro-German maverick socialist Alexander Parvus

Alexander Lvovich Parvus, born Israel Lazarevich Gelfand (8 September 1867 – 12 December 1924) and sometimes called Helphand in the literature on the Russian Revolution, was a Marxist theoretician, publicist, and controversial activist in the ...

. His independence was consequently challenged by the interventionist paper ''Adevărul

''Adevărul'' (; meaning "The Truth", formerly spelled ''Adevĕrul'') is a Romanian daily newspaper, based in Bucharest. Founded in Iași, in 1871, and reestablished in 1888, in Bucharest, it was the main left-wing press venue to be published du ...

'', a former socialist venue, who called Rakovsky "an adventurer without scruples", and viewed him as employed by Parvus and other German socialists.

Rakovsky himself alleged that, "under the mask of independence", ''Adevărul'' and its editor Constantin Mille were in the pay of Take Ionescu. After Romania's entry into the conflict on the side of the Entente in August 1916, having failed to attend the Kienthal Conference The Kienthal Conference (also known as the Second Zimmerwald Conference) was held, in the Swiss village of Kienthal, between April 24 and 30, 1916. Like its 1915 predecessor, the Zimmerwald Conference, it was an international conference of socialist ...

due to the closure of borders,Fagan, ''Regroupment of the socialist movement''; Rakovsky, ''An Autobiography''. he was placed under surveillance and ultimately imprisoned in September, based on the belief that he was acting as a German spy.

As Bucharest fell to the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

during the 1916 campaign, he was taken by Romanian authorities to their refuge in Iaşi. Held until after the February Revolution

The February Revolution ( rus, Февра́льская револю́ция, r=Fevral'skaya revolyutsiya, p=fʲɪvˈralʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and some ...

, he was freed by the Russian Army on May 1, 1917, and immediately left for Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

.

October Revolution

Rakovsky moved toPetrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

(the new name of Saint Petersburg) in the spring of 1917. His anti-war activism almost got him arrested; Rakovsky managed to flee in August, and was present in Stockholm

Stockholm () is the capital and largest city of Sweden as well as the largest urban area in Scandinavia. Approximately 980,000 people live in the municipality, with 1.6 million in the urban area, and 2.4 million in the metropo ...

for the Third Zimmerwald Conference; he remained there and, with Karl Radek

Karl Berngardovich Radek (russian: Карл Бернгардович Радек; 31 October 1885 – 19 May 1939) was a Russian revolutionary and a Marxist active in the Polish and German social democratic movements before World War I and a ...

, issued propaganda material in support of the Russian revolutionaries. Present in the internationalist

Internationalist may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Liberal internationalism, a doctrine in international relations

* Internationalist/Defencist Schism, socialists opposed to ...

faction of the Mensheviks, he joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

s in December 1917 or early 1918, after the October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key mom ...

(although he was occasionally listed among the Old Bolsheviks

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

).George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalit ...

, "Arthur Koestler. Essay". Retrieved 19 July 2007. Rakovsky later stated that he had friendly relations with the Bolsheviks from early autumn 1917, when, during the attempted putsch of Lavr Kornilov

Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov (russian: Лавр Гео́ргиевич Корни́лов, ; – 13 April 1918) was a Russian military intelligence officer, explorer, and general in the Imperial Russian Army during World War I and the ensuing Rus ...

, he was hidden by these in Sestroretsk

Sestroretsk (russian: Сестроре́цк; fi, Siestarjoki; sv, Systerbäck) is a municipal town in Kurortny District of the federal city of St. Petersburg, Russia, located on the shores of the Gulf of Finland, the Sestra River ...

.

His rise in influence and his approval of world revolution led him to seek Lenin's support for a Bolshevik government over Romania, at a time when a similar attempt was being made by the Odessa-based ''Romanian Social Democratic Action Committee'', under the guidance of Mihai Gheorghiu Bujor; Stelian Tănase claims that during the period, a group of one hundred Russian Bolsheviks had infiltrated Iaşi with the goal of assassinating King

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen regnant, queen, which title is also given to the queen consort, consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contempora ...

Ferdinand I and organizing a coup. Eventually, Lenin decided in favor of a unified project, and called on Bujor and Rakovsky to form a single leadership (which also included the Romanian expatriates Alecu Constantinescu and Ion Dic Dicescu).

As the coup was under preparation in December 1917, Rakovsky was present on the border and waiting a signal to enter the country. When Bolsheviks were arrested and the move was overturned, he was probably responsible for ordering the arrest of Romania's representative to Petrograd, Constantin I. Diamandy, and his entire staff (all of whom were used as hostage

A hostage is a person seized by an abductor in order to compel another party, one which places a high value on the liberty, well-being and safety of the person seized, such as a relative, employer, law enforcement or government to act, or refr ...

s, pending the release of prisoners taken in Iaşi). Trotsky, who was by then Russia's People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs (Foreign Minister

A foreign affairs minister or minister of foreign affairs (less commonly minister for foreign affairs) is generally a cabinet minister in charge of a state's foreign policy and relations. The formal title of the top official varies between co ...

), called on the Romanian government of Ion I. C. Brătianu

Ion Ionel Constantin Brătianu (, also known as Ionel Brătianu; 20 August 1864 – 24 November 1927) was a Romanian politician, leader of the National Liberal Party (PNL), Prime Minister of Romania for five terms, and Foreign Minister on se ...

to hand in persons captured, indicating that he would otherwise encourage the communist activities of Romanian refugees on Russian soil, and receiving a reply according to which no such arrests had occurred.

At the same time, Rakovsky regained Odessa, where he became a leader of the Bolshevik administrative body ('' Rumcherod''), and, according to the claims of Stelian Tănase, ordered violent reprisals to be aimed at Romanian nationals present in the city, and issued agitprop

Agitprop (; from rus, агитпроп, r=agitpróp, portmanteau of ''agitatsiya'', "agitation" and ''propaganda'', " propaganda") refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in Soviet Russia where it referred ...

literature in Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

** Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditiona ...

.

As Russia negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (also known as the Treaty of Brest in Russia) was a separate peace treaty signed on 3 March 1918 between Russia and the Central Powers ( Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria, and the Ottoman Empire), that ended Russi ...

with Germany, he ordered ''Rumcherod'' troops to march towards Romania, which was by then giving in to the German advances and preparing to sign its own peace. Initially stalled by a much-criticized temporary armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

with Romanian Army

The Romanian Land Forces ( ro, Forțele Terestre Române) is the army of Romania, and the main component of the Romanian Armed Forces. In recent years, full professionalisation and a major equipment overhaul have transformed the nature of the Lan ...

leader Alexandru Averescu, Rakovsky ordered a fresh offensive in Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

, but had to retreat when the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,german: Mittelmächte; hu, Központi hatalmak; tr, İttifak Devletleri / ; bg, Централни сили, translit=Tsentralni sili was one of the two main coalitions that fought in W ...

, confronted with Trotsky's refusal to accept their version of a Russo-German peace, began their own military operation and occupied Odessa (setting free Romanians who had been imprisoned there). On 9 March 1918, Rakovsky signed a treaty with Romania regarding the evacuation of troops from Bessarabia, which Stelian Tănase claims allowed for the Moldavian Democratic Republic

The Moldavian Democratic Republic (MDR; ro, Republica Democratică Moldovenească, ), also known as the Moldavian Republic, was a state proclaimed on by the '' Sfatul Țării'' (National Council) of Bessarabia, elected in October–Novemb ...

to join Romania. In May, Romania conceded to the demands of the Central Powers (''see Treaty of Bucharest, 1918''). In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the

In April–May 1918, he negotiated with the Tsentral'na Rada

The Central Council of Ukraine ( uk, Українська Центральна Рада, ) (also called the Tsentralna Rada or the Central Rada) was the All-Ukrainian council (soviet) that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputie ...

of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR), or Ukrainian National Republic (UNR), was a country in Eastern Europe that existed between 1917 and 1920. It was declared following the February Revolution in Russia by the First Universal. In March 1 ...

, then with the Hetmanate of Pavlo Skoropadsky