Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (30 January 1723,

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (30 January 1723,

''Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb''

Band 17, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig (1883). During the years 1733-1742 he attended the

''Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb''

Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin (1980). In 1742 Kratzenstein started to study

'' Maximilianus Hell (1720-1792) and the Eighteenth-Century Transits of Venus''

University of

Already during his upbringing in Wernigerode had Kratzenstein become acquainted with

Already during his upbringing in Wernigerode had Kratzenstein become acquainted with

After the first observed

After the first observed

''Kann was natürlicher, als Vox humana, klingen? Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der mechanischen Sprachsynthese''

PhD thesis, Universitetet i At the final evaluation by the academy in 1780, it was Kratzenstein's "vowel organ" that got the first prize. His contribution ''Tentamen resolvendi problema'' was published the year after. It consisted of a first part describing how the vowels could be produced in the

At the final evaluation by the academy in 1780, it was Kratzenstein's "vowel organ" that got the first prize. His contribution ''Tentamen resolvendi problema'' was published the year after. It consisted of a first part describing how the vowels could be produced in the

''Akustik des Sprechens''

Universität Duisburg-Essen. * C. Korpiun

Universität Duisburg-Essen. {{DEFAULTSORT:Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb 18th-century German physicists 1723 births 1795 deaths Rectors of the University of Copenhagen People from Wernigerode

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (30 January 1723,

Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (30 January 1723, Wernigerode

Wernigerode () is a town in the district of Harz, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Until 2007, it was the capital of the district of Wernigerode. Its population was 35,041 in 2012.

Wernigerode is located southwest of Halberstadt, and is picturesquely s ...

– 6 July 1795, Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

) was a German-born doctor

Doctor or The Doctor may refer to:

Personal titles

* Doctor (title), the holder of an accredited academic degree

* A medical practitioner, including:

** Physician

** Surgeon

** Dentist

** Veterinary physician

** Optometrist

*Other roles

** ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

and engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

. From 1753 to the end of his life he was a professor at the University of Copenhagen

The University of Copenhagen ( da, Københavns Universitet, KU) is a prestigious public university, public research university in Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Founded in 1479, the University of Copenhagen is the second-oldest university in ...

where he served as rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

four times. He is especially known for his investigations of the use of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

in medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

and the first attempts at mechanical speech synthesis

Speech synthesis is the artificial production of human speech. A computer system used for this purpose is called a speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or hardware products. A text-to-speech (TTS) system converts normal languag ...

. As a teacher he wrote the first textbook on experimental physics

Experimental physics is the category of disciplines and sub-disciplines in the field of physics that are concerned with the observation of physical phenomena and experiments. Methods vary from discipline to discipline, from simple experiments and ...

in the united kingdom of Denmark-Norway.

Biography

Kratzenstein was baptized on 2 February 1723 in Wernigerode,Sachsen-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it the ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and grew up there in an academic family together with three brothers. His father gave them a good upbringing and education.E. Jacobs, Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie''Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb''

Band 17, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig (1883). During the years 1733-1742 he attended the

Latin school

The Latin school was the grammar school of 14th- to 19th-century Europe, though the latter term was much more common in England. Emphasis was placed, as the name indicates, on learning to use Latin. The education given at Latin schools gave gre ...

in the same city. Already at this age he was recognized for his interests in reading and learning. He was especially fascinated by the latest discoveries within the natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

s and mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

.W.D. Kühnelt, Neue Deutsche Biographie''Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb''

Band 12, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin (1980). In 1742 Kratzenstein started to study

physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

at the university in Halle which at that time had a leading position in that region. His interests turned now to the investigations of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

and in particular the effects on living organisms.E. Snorrason, ''C.G. Kratzenstein, professor physices experimentalis Petropol. et Havn. and his studies on electricity during the eighteenth century'', Odense University Press (1974). . After four years he received in 1746 doctoral degrees

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''l ...

in physics and in medicine. He was then only 23 years old. After two years as a privatdozent

''Privatdozent'' (for men) or ''Privatdozentin'' (for women), abbreviated PD, P.D. or Priv.-Doz., is an academic title conferred at some European universities, especially in German-speaking countries, to someone who holds certain formal qualific ...

he was in 1748 elected to the Academy of Sciences Leopoldina

The German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina (german: Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina – Nationale Akademie der Wissenschaften), short Leopoldina, is the national academy of Germany, and is located in Halle (Saale). Founded ...

in the same city.

At that time Kratzenstein had achieved international recognition and was in 1748 called to the science academy in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

. It is likely that Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries in ma ...

, who had worked there earlier before he took up a new position at the Prussian Academy of Sciences

The Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (german: Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften) was an academy established in Berlin, Germany on 11 July 1700, four years after the Prussian Academy of Arts, or "Arts Academy," to which "Berlin ...

in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, had used his influence in this connection. He had corresponded with Kratzenstein over a period of several years.

In his new position Kratzenstein worked among other projects on improving instruments for navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

on the open seas. These were tried out in 1753 on a ship expedition from Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

along the Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

coast through Kattegat

The Kattegat (; sv, Kattegatt ) is a sea area bounded by the Jutlandic peninsula in the west, the Danish Straits islands of Denmark and the Baltic Sea to the south and the provinces of Bohuslän, Västergötland, Halland and Skåne in Sweden ...

and the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

back to Saint Petersburg. During the voyage he had made a stop-over in Copenhagen and received a short time later an offer from the university there. In the fall of 1753 he was appointed professor of experimental physics

Experimental physics is the category of disciplines and sub-disciplines in the field of physics that are concerned with the observation of physical phenomena and experiments. Methods vary from discipline to discipline, from simple experiments and ...

and medicine. At the same time he was elected to the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters

{{Infobox organization

, name = The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters

, full_name =

, native_name = Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab

, native_name_lang =

, logo = Royal ...

. He would remain in that city until his death.Susan Splinter, ''Zwischen Nützlichkeit und Nachahmung : Eine Biografie des Gelehrten Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein (1723-1795)'', P. Lang, (2006). ,

Kratzenstein became known in a short time as an engaging lecturer and attracted a large audience of both regular students and interested persons from the citizenry. He covered topics ranging from the newest insights about plants and animals, through geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

, physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemical ...

to physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

and chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

. At that time there were often rather diffuse separations between these disciplines. When he died, he had saved 12000 riksdaler

The svenska riksdaler () was the name of a Swedish coin first minted in 1604. Between 1777 and 1873, it was the currency of Sweden. The daler, like the dollar,''National Geographic''. June 2002. p. 1. ''Ask Us''. was named after the German Thaler. ...

which were bestowed to the university. A few years later this fund enabled Hans Christian Ørsted

Hans Christian Ørsted ( , ; often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 17779 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity ...

to build up his own laboratory for physical experiments.D.C. Christensen, ''Hans Christian Ørsted: Reading Nature's Mind'', Oxford University Press, Oxford (2013). .

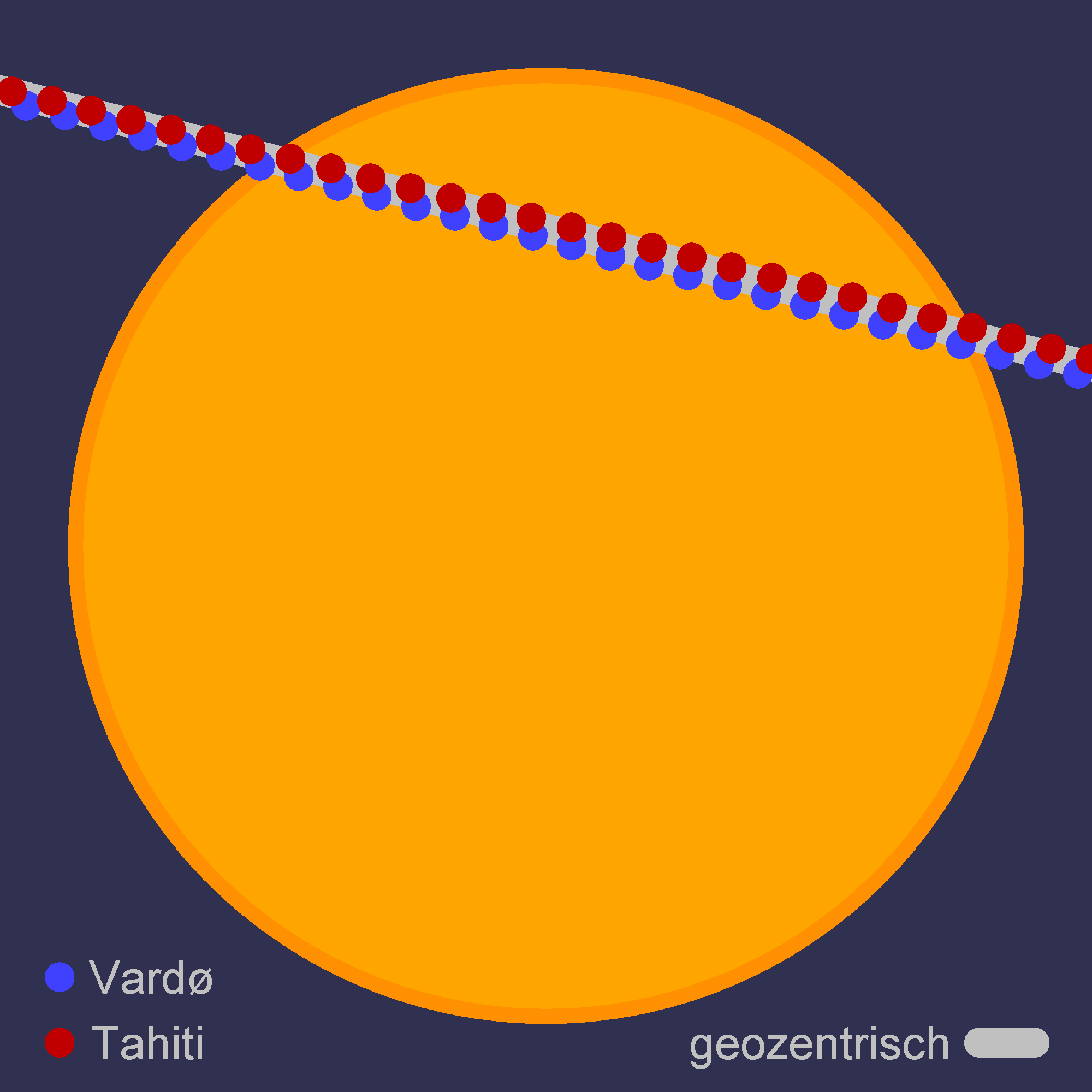

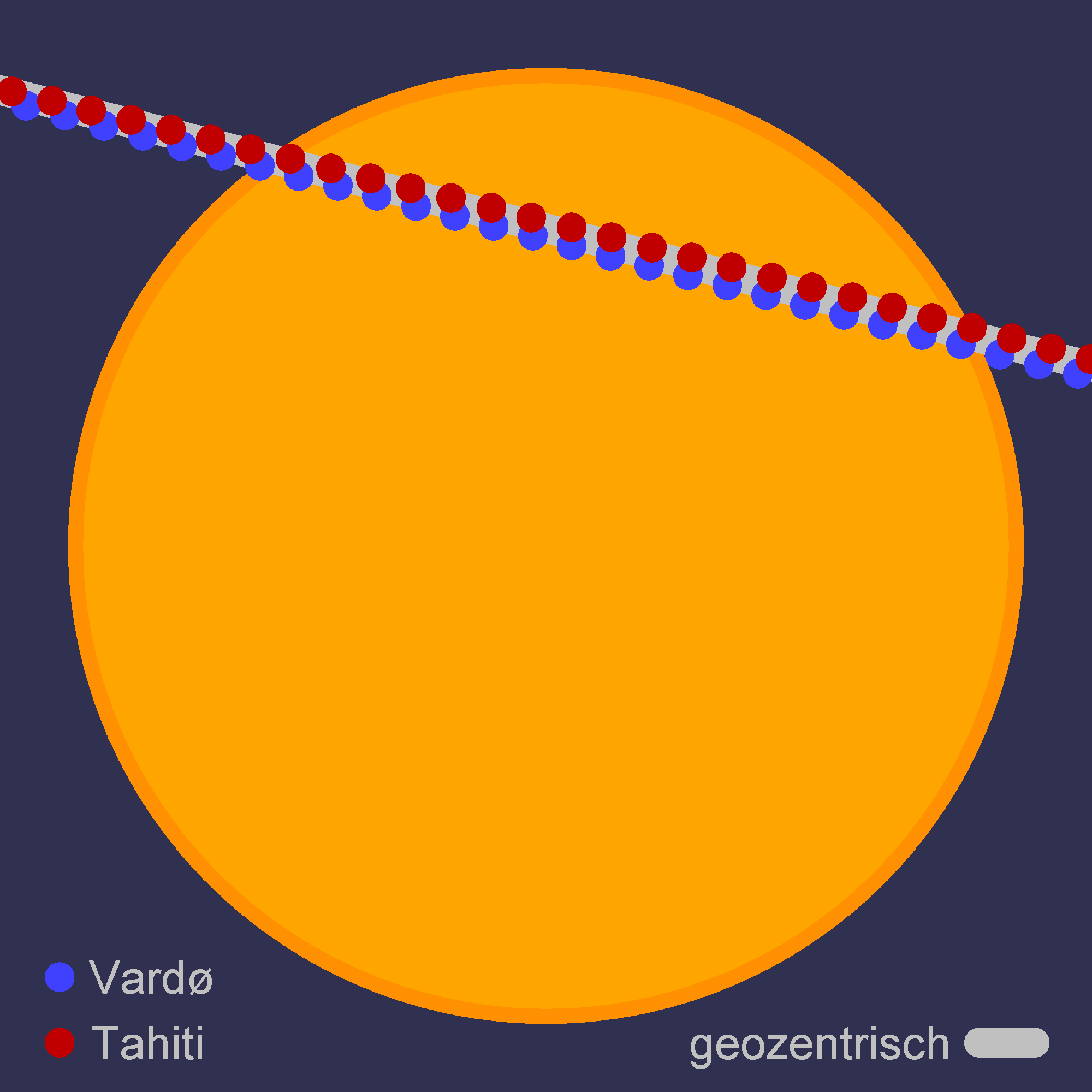

His work at the university strengthened the academic standards and manifested itself in many ways. Thus it was Kratzenstein who seized the initiative before the important transits of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a tran ...

in 1761 and 1769 instead of the astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. They observe astronomical objects such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, g ...

s at the Rundetårn

The Round Tower (Danish: Rundetårn) is a 17th-century tower in Copenhagen, Denmark, one of the many architectural projects of Christian IV of Denmark. Built as an astronomical observatory, it is noted for its equestrian staircase, a 7.5-turn hel ...

observatory.P. Pippin Aspaas'' Maximilianus Hell (1720-1792) and the Eighteenth-Century Transits of Venus''

University of

Tromsø

Tromsø (, , ; se, Romsa ; fkv, Tromssa; sv, Tromsö) is a List of municipalities of Norway, municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the Tromsø (city), city of Tromsø.

Tromsø lies ...

(2012). In order to spread the impact of his lectures he wrote a textbook in experimental physics. It was published in several editions and appeared in German, French and Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

in addition to the Danish version. As a result of all his efforts and engagements he served as rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

at the university during four periods.

During his time in Copenhagen he maintained contacts with his former colleagues in Saint Petersburg. The science academy there announced in 1778 a prize competition concerning the mechanisms behind the vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s A, E, I, O and U in human speech

Speech is a human vocal communication using language. Each language uses phonetic combinations of vowel and consonant sounds that form the sound of its words (that is, all English words sound different from all French words, even if they are th ...

. Euler had previously been interested in this problem and it is likely that he was behind the formulation of the task.C.G. Kratzenstein, ''Tentamen resolvendi problema'', translated to German by C. Korpiun, Band 82, Studientexte zur Sprachkommunikation (ed R. Hoffmann), TUDpress, Dresden (2016). . Kratzenstein won the first prize in 1780 by constructing a «vowel organ» which could produce these special sounds. This represents one of the first contributions to modern speech synthesis

Speech synthesis is the artificial production of human speech. A computer system used for this purpose is called a speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or hardware products. A text-to-speech (TTS) system converts normal languag ...

.

By his wide range of engagements and temperament Kratzenstein would often end up in conflicts with his colleagues. In later years he suffered in addition from illnesses which could have been caused by his chemical experiments. After his wife Anna Margrethe Hagen, with whom he had four children, died in 1783, he actively sought a new wife and married the year after Anna Maria Thuun from Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

. At the big fire in Copenhagen 1795 he lost most of his possessions and scientific equipment. He moved out to the suburb Frederiksberg

Frederiksberg () is a part of the Capital Region of Denmark. It is formally an independent municipality, Frederiksberg Municipality, separate from Copenhagen Municipality, but both are a part of the City of Copenhagen. It occupies an area of ...

where he died a month later.

Important contributions

Kratzenstein was apolymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and a typical representative of the Enlightenment. New ideas and discoveries were changing the understanding of the world. Observations and experiments should replace old dogmas and superstition. This conviction characterized the whole life of Kratzenstein whose curiosity led him in many directions. He excelled more by practical investigations and building of instruments than by developing new theoretical insights that would survive his own times.

Body and soul

As a student in Halle Kratzenstein made his first step to fame by his pamphlet ''Beweis, dass die Seele ihren Körper baue'' in 1743. This was typical for the philosophical discourse at the university at that time. In this work he discussed the location of the soul in the body and how living organisms can continue to function after amputations and other severe changes to the body. If animals also had a soul, one had to explain what it does in a polyp which can grow up from a smaller part of an existing polyp. Such questions continued to occupy him in the following years in Halle where he also investigatedparasites

Parasitism is a Symbiosis, close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the Host (biology), host, causing it some harm, and is Adaptation, adapted structurally to this way of lif ...

in the human body, for example tapeworms

Cestoda is a class of parasitic worms in the flatworm phylum (Platyhelminthes). Most of the species—and the best-known—are those in the subclass Eucestoda; they are ribbon-like worms as adults, known as tapeworms. Their bodies consist of man ...

.

At the same time in 1744 he also wrote the essay ''Théorie sur l'Elévation des Vapeurs et des Exhalaisons dans l'Air'' in a prize competition announced by the science academy in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

. Here he is the physicist trying to arrive at a more microscopic explanation of what today is called gas

Gas is one of the four fundamental states of matter (the others being solid, liquid, and plasma).

A pure gas may be made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon), elemental molecules made from one type of atom (e.g. oxygen), or ...

es and vapor

In physics, a vapor (American English) or vapour (British English and Canadian English; see spelling differences) is a substance in the gas phase at a temperature lower than its critical temperature,R. H. Petrucci, W. S. Harwood, and F. G. Her ...

s. He estimated that a drop of water would transform into five hundred million smaller pieces by evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humidi ...

.

Electricity and electrotherapy

Already during his upbringing in Wernigerode had Kratzenstein become acquainted with

Already during his upbringing in Wernigerode had Kratzenstein become acquainted with electrostatic generator

An electrostatic generator, or electrostatic machine, is an electrical generator that produces ''static electricity'', or electricity at high voltage and low continuous current. The knowledge of static electricity dates back to the earliest ci ...

s and seen the effects an electric current

An electric current is a stream of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is measured as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface or into a control volume. The moving pa ...

could have. This interest he widened during his studies in Halle with a special emphasis on the potential use of electricity in medicine. His thoughts in this direction he published in 1744 under the title ''Abhandlung von dem Nutzen der Electricität in der Arzeneiwissenschaft''. From experiments and observations he had seen how electricity could affect the human pulse

In medicine, a pulse represents the tactile arterial palpation of the cardiac cycle (heartbeat) by trained fingertips. The pulse may be palpated in any place that allows an artery to be compressed near the surface of the body, such as at the nec ...

and perspiration

Perspiration, also known as sweating, is the production of fluids secreted by the sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distrib ...

. In the same way he saw how electrical discharges could heal certain neurological disorder

A neurological disorder is any disorder of the nervous system. Structural, biochemical or electrical abnormalities in the brain, spinal cord or other nerves can result in a range of symptoms. Examples of symptoms include paralysis, muscle weakn ...

s. These ideas were later taken up by others and developed into what today is generically called electrotherapy

Electrotherapy is the use of electrical energy as a medical treatment. In medicine, the term ''electrotherapy'' can apply to a variety of treatments, including the use of electrical devices such as deep brain stimulators for neurological dise ...

.

Based on these ideas and investigations by Kratzenstein there have been speculations that he could have been a model for the fictitious doctor Frankenstein in the book of the same name written by Mary Shelley

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (; ; 30 August 1797 – 1 February 1851) was an English novelist who wrote the Gothic fiction, Gothic novel ''Frankenstein, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus'' (1818), which is considered an History of scie ...

several decades later.

Two years later Kratzenstein wrote the more theoretical work ''Theoria electricitatis mores geometrica explicata'' on the nature of electricity. Around this time he made measurements to find out how the electric force between two charged objects varied with their separation. On the theoretical side he argued that the electrical current was due to the motion of two fluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that continuously deforms (''flows'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are substances which cannot resist any shear ...

s which today would correspond to the flow of positive and negative electric charge

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes charged matter to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative'' (commonly carried by protons and electrons respe ...

s. The charges themselves should be due to vortices

In fluid dynamics, a vortex ( : vortices or vortexes) is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in th ...

in these fluids. Around the same time Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

explained the same phenomena based on a one-fluid picture where negative charge was due to a lack of positive charge. It was this explanation that prevailed.

Together with a similar thesis about bodily fluids and their properties, Kratzenstein received in 1746 a doctor's degree both in physics and in medicine.

Navigation

During the five years at the science academy in Saint Petersburg Kratzenstein was to a large extent occupied by improving methods and equipment for navigation on thehigh seas

The terms international waters or transboundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water (or their drainage basins) transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed regiona ...

. The magnetic compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

was made more reliable, astronomical observations should be made more precise together with the development of more accurate clock

A clock or a timepiece is a device used to measure and indicate time. The clock is one of the oldest human inventions, meeting the need to measure intervals of time shorter than the natural units such as the day, the lunar month and the ...

s to be used on ships for the determination of geographical longitude

Longitude (, ) is a geographic coordinate that specifies the east–west position of a point on the surface of the Earth, or another celestial body. It is an angular measurement, usually expressed in degrees and denoted by the Greek letter l ...

.

These new instruments were tried out on the voyage from Arkhangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ; rus, Арха́нгельск, p=ɐrˈxanɡʲɪlʲsk), also known in English as Archangel and Archangelsk, is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies o ...

to Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in 1753 Kratzenstein discovered that the Norwegian

Norwegian, Norwayan, or Norsk may refer to:

*Something of, from, or related to Norway, a country in northwestern Europe

* Norwegians, both a nation and an ethnic group native to Norway

* Demographics of Norway

*The Norwegian language, including ...

coast was placed 150 km too far east on contemporary maps. This can seem unlikely due to the lack of accuracy of the watches being used. Many years later in 1793 Kratzenstein received a prize from the academy in Saint Petersburg for these observations and other magnetic measurements made on the same voyage.

Mathematical Calculation

In April 1765 at Saint Petersburg, Kratzenstein presented to the Russian Academy of Sciences a perfected version of the stepped reckoner arithmetical machine originally invented byGottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

. Kratzenstein claimed that his machine solved the problem the Leibniz machine had with calculations above four digits, perfecting the flaw where the machine is "prone to err whenever it is necessary to make a number of 9999 move to 10000", but the machine was not developed further.Matthew L. Jones, ''Reckoning with Matter: Calculating Machines, Innovation, and Thinking about Thinking from Pascal to Babbage'' (University of Chicago Press, 2016) p133

Transits of Venus

After the first observed

After the first observed transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a trans ...

in 1619, Edmund Halley

Edmond (or Edmund) Halley (; – ) was an English astronomer, mathematician and physicist. He was the second Astronomer Royal in Britain, succeeding John Flamsteed in 1720.

From an observatory he constructed on Saint Helena in 1676–77, Ha ...

had stressed the importance of the two upcoming transits in 1761 and 1769. Also in the Nordic countries there was great interest in taking part in these observations. In Copenhagen it was the astronomers in the local observatory Rundetårn

The Round Tower (Danish: Rundetårn) is a 17th-century tower in Copenhagen, Denmark, one of the many architectural projects of Christian IV of Denmark. Built as an astronomical observatory, it is noted for its equestrian staircase, a 7.5-turn hel ...

who formally were responsible for such activities. But in practice it was Kratzenstein who became the leader of this endeavour. In public lectures before the transit in 1761 he presented the theoretical background for this rare phenomenon and calculated transit times together with suggestions for suitable places of observation.

For the first transit he thus knew that it would be important to make the measurements further nord. He thus organized an expedition to Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

consisting of two students. One of them was Thomas Bugge

Thomas Bugge (12 October 1740 – 15 January 1815) was a Danish astronomer, mathematician and surveyor. He succeeded Christian Horrebow as professor of astronomy at the University of Copenhagen in 1777. His triangulation surveys of Denmark carri ...

, who was then 20 years old and later would become an astronomer and important land surveyor

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is c ...

in Denmark. The other student was Urban Bruun Aaskow, who was even younger and studied medicine. Because of bad weather their observations in Trondheim were of little use. In Copenhagen the weather conditions were much better, but there the observations in Rundetårn failed due to inaccurate clocks.

The next transit in the summer of 1769 would take place during the night in the continental Europe and could thus not so easily be observed. But north of the polar circle

A polar circle is a geographic term for a conditional circular line (arc) referring either to the Arctic Circle or the Antarctic Circle. These are two of the keynote circles of latitude (parallels). On Earth, the Arctic Circle is currently ...

there would be midnight sun

The midnight sun is a natural phenomenon that occurs in the summer months in places north of the Arctic Circle or south of the Antarctic Circle, when the Sun remains visible at the local midnight. When the midnight sun is seen in the Arctic, t ...

and thus ideal for observations. The united kingdom Denmark-Norway could therefore make important contributions to this transit. Thus by a royal decree from Christian VII

Christian VII (29 January 1749 – 13 March 1808) was a monarch of the House of Oldenburg who was King of Denmark–Norway and Duke of Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswig and Duchy of Holstein, Holstein from 1766 until his death in 1808. For his motto ...

an expedition to the northernmost military post in Vardø

( fi, Vuoreija, fkv, Vuorea, se, Várggát) is a municipality in Troms og Finnmark county in the extreme northeastern part of Norway. Vardø is the easternmost town in Norway, more to the east than Saint Petersburg or Istanbul. The administra ...

was established. But in this process Kratzenstein was sidelined in favour of the Hungarian astronomer Maximilian Hell

Maximilian Hell ( hu, Hell Miksa) (born Rudolf Maximilian Höll; May 15, 1720 – April 14, 1792) was an astronomer and an ordained Jesuit priest from the Kingdom of Hungary.

Biography

Born as Rudolf Maximilian Höll in Selmecbánya, Hont Co ...

. The expedition was successful and the observations turned out to be of great value.

A disappointed Kratzenstein had in the meantime organized a private expedition to Trondheim. On the way there it suffered a shipwreck where Kratzenstein saved himself by swimming ashore. He reached Tronheim barely in time but bad weather made meaningful observations impossible.

Speech synthesis

The physical understanding ofsound waves

In physics, sound is a vibration that propagates as an acoustic wave, through a transmission medium such as a gas, liquid or solid.

In human physiology and psychology, sound is the ''reception'' of such waves and their ''perception'' by the ...

was established around 1750 by Leonhard Euler

Leonhard Euler ( , ; 15 April 170718 September 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries in ma ...

and others. From 1766 Euler was again back at the science academy in Saint Petersburg. In a letter from 1773 he asked the question how speech could arise from the flow of air through the vocal folds

In humans, vocal cords, also known as vocal folds or voice reeds, are folds of throat tissues that are key in creating sounds through vocalization. The size of vocal cords affects the pitch of voice. Open when breathing and vibrating for speech ...

and tract

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

...

. An unanswered question was related to what tonal qualities characterised the different letters when spoken. Euler speculated that it should perhaps be possible to build some kind of musical instrument which could produce similar sounds and string them together to understandable words. One possibility was to build on the existing vox humana which could be found in some pipe organ

The pipe organ is a musical instrument that produces sound by driving pressurized air (called ''wind'') through the organ pipes selected from a keyboard. Because each pipe produces a single pitch, the pipes are provided in sets called ''ranks ...

s. The result would then be a mechanical speech synthesizer

Speech synthesis is the artificial production of human speech. A computer system used for this purpose is called a speech synthesizer, and can be implemented in software or Computer hardware, hardware products. A text-to-speech (TTS) system conve ...

. He pointed also out that the vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (leng ...

s would be of special importance.F. Brackhane''Kann was natürlicher, als Vox humana, klingen? Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der mechanischen Sprachsynthese''

PhD thesis, Universitetet i

Saarland

The Saarland (, ; french: Sarre ) is a state of Germany in the south west of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and ...

(2015).

Kratzenstein had followed this discussion since he remained in contact with Euler and already from 1770 had been investigating the same problems. From his textbooks in experimental physics it is clear that he had a good understanding of the physics behind sound. It was therefore not so surprising that the academy in Saint Petersburg in 1778 announced a new prize problem exactly around these questions. The first part should investigate the tonal differences between the five vowels A, E, I, O and U, while the latter part asked for a device which could generate these sounds.

vocal tract

The vocal tract is the cavity in human bodies and in animals where the sound produced at the sound source ( larynx in mammals; syrinx in birds) is filtered.

In birds it consists of the trachea, the syrinx, the oral cavity, the upper part of th ...

. His medical background was here of great help. The second part was the construction of a new kind of organ with pipes for each of the vowels. Each pipe had a characteristic resonant cavity

A resonator is a device or system that exhibits resonance or resonant behavior. That is, it naturally oscillates with greater amplitude at some frequencies, called resonant frequencies, than at other frequencies. The oscillations in a resonato ...

which should emulate the vocal tract for the corresponding vowel. In order to excite these resonators he made use of free reeds which at that time were little known.

This instrument was demonstrated in Saint Petersburg to the full satisfaction of the academy, but was damaged and disappeared shortly afterwards. But the use of free reeds in musical instruments became later widespread and can today be found in the harmonica

The harmonica, also known as a French harp or mouth organ, is a free reed wind instrument used worldwide in many musical genres, notably in blues, American folk music, classical music, jazz, country, and rock. The many types of harmonica inclu ...

, accordion

Accordions (from 19th-century German ''Akkordeon'', from ''Akkord''—"musical chord, concord of sounds") are a family of box-shaped musical instruments of the bellows-driven free-reed aerophone type (producing sound as air flows past a reed ...

, harmonium

The pump organ is a type of free-reed organ that generates sound as air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame. The piece of metal is called a reed. Specific types of pump organ include the reed organ, harmonium, and melodeon. T ...

and bandoneon

The bandoneon (or bandonion, es, bandoneón) is a type of concertina particularly popular in Argentina and Uruguay. It is a typical instrument in most tango ensembles. As with other members of the concertina family, the bandoneon is held bet ...

. It is not known how Kratzenstein got the idea to use them, but they had for a long time been a central part of the Chinese musical instrument sheng.

References

Further reading

* Sieghard Scheffczyk: ''Aus Wernigerode nach Europa – Das bewegte Leben des Christian Gottlieb Kratzendsten''. In ''Neue Wernigeröder Zeitung''; 4, 2011, p. 21External links

* C. Korpiun''Akustik des Sprechens''

Universität Duisburg-Essen. * C. Korpiun

Universität Duisburg-Essen. {{DEFAULTSORT:Kratzenstein, Christian Gottlieb 18th-century German physicists 1723 births 1795 deaths Rectors of the University of Copenhagen People from Wernigerode