Chiricahua Apache on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chiricahua ( ) is a band of

They made a stronghold in the

They made a stronghold in the

In the Chiricahua culture, the "band" as a unit was much more important than the

American or European concept of "tribe". The Chiricahua had no name for themselves (autonym) as a people. The name Chiricahua is most likely the Spanish rendering of the

In the Chiricahua culture, the "band" as a unit was much more important than the

American or European concept of "tribe". The Chiricahua had no name for themselves (autonym) as a people. The name Chiricahua is most likely the Spanish rendering of the

The Cerro Rojo Site (LA 37188) – A Large Mountain-Top Ancestral Apache Site in Southern New Mexico

Digital History Project. New Mexico Office of the State Historian. * Seymour, Deni J. (2010) Cycles of Renewal, Transportable Assets: Aspects of the Ancestral Apache Housing Landscape. Accepted at Plains Anthropologist. * Seymour, Deni J. (2010) Contextual Incongruities, Statistical Outliers, and Anomalies: Targeting Inconspicuous Occupational Events. American Antiquity. (Winter, in press)

Fort Sill Apache Tribe

official website

Mescalero Apache Tribe

official website

Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache Texts

Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache artist

National Park Service {{DEFAULTSORT:Chiricahua Apache tribes Chiricahua Mountains History of Catron County, New Mexico Indigenous peoples in Mexico Native American history of Arizona Native American history of New Mexico Native American tribes in Arizona Native American tribes in New Mexico Native American tribes in Oklahoma

Apache

The Apache () are a group of culturally related Native American tribes in the Southwestern United States, which include the Chiricahua, Jicarilla, Lipan, Mescalero, Mimbreño, Ndendahe (Bedonkohe or Mogollon and Nednhi or Carrizaleño a ...

Native Americans.

Based in the Southern Plains and Southwestern United States, the Chiricahua (Tsokanende ) are related to other Apache groups: Ndendahe (Mogollon, Carrizaleño), Tchihende (Mimbreño), Sehende (Mescalero), Lipan, Salinero, Plains

In geography, a plain is a flat expanse of land that generally does not change much in elevation, and is primarily treeless. Plains occur as lowlands along valleys or at the base of mountains, as coastal plains, and as plateaus or uplands.

In ...

, and Western Apache. Chiricahua historically shared a common area, language, customs, and intertwined family relations with their fellow Apaches. At the time of European contact, they had a territory of 15 million acres (61,000 km2) in Southwestern New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe, New Mexico, Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque, New Mexico, Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Albuquerque metropolitan area, Tiguex

, Offi ...

and Southeastern Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

in the United States and in Northern Sonora

Sonora (), officially Estado Libre y Soberano de Sonora ( en, Free and Sovereign State of Sonora), is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the Federal Entities of Mexico. The state is divided into 72 municipalities; the ...

and Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

in Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

.

Today Chiricahua are enrolled in three federally recognized tribe

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the Unite ...

s in the United States: the Fort Sill Apache Tribe

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.

Government

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is headquartered in Apache, Oklahoma. Tribal member enrollment, which requires a ...

, located near Apache, Oklahoma

Apache is a town in Caddo County, Oklahoma, United States. The population was 1,444 at the 2010 census.

History

Before opening the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Reservation on August 1, 1901, for unrestricted settlement by non-Indians, Land Lott ...

, with a small reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

outside Deming, New Mexico

Deming (, ''DEM-ing'') is a city in Luna County, New Mexico, United States, west of Las Cruces and north of the Mexican border. The population was 14,855 as of the 2010 census. Deming is the county seat and principal community of Luna County ...

; the Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico; and the San Carlos Apache Tribe

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation ( Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed f ...

in southeastern Arizona.

Name

The Chiricahua Apache, also written as ''Chiricagui'', ''Apaches de Chiricahui'', ''Chiricahues'', ''Chilicague'', ''Chilecagez'', and ''Chiricagua'', were given that name by the Spanish. The White Mountain Coyotero Apache, including the ''Cibecue'' and ''Bylas'' groups of the Western Apache, referred to the Chiricahua by the name ''Ha'i’ą́há'', while the San Carlos Apache called them ''Hák'ą́yé'' which means ″Eastern Sunrise″, or ″People in the East″. Sometimes they adapted this appellation and referred to themselves also as ''Ha’ishu Na gukande'' ('Sunrise People'). The Mescalero Apache called the Western Apache and Chiricahua bands to their west ''Shá'i'áõde'' ("Western Apache People", "The People of the Sunset", "The People of the West"), when referring only to Chiricahuas they used ''Ch'úk'ânéõde'' ("People of a ridge or mountainside ade of loose rocks) or sometimes ''Tã'aa'ji k'ee'déõkaa'õde'' ("The Ones who are Covered ith breech cloths).Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest fe ...

refer to the Chiricahua as ''Chíshí'' ("Southern People").

The Chiricahua autonym

Autonym may refer to:

* Autonym, the name used by a person to refer to themselves or their language; see Exonym and endonym

* Autonym (botany), an automatically created infrageneric or infraspecific name

See also

* Nominotypical subspecies, in zo ...

, or name by which they refer to themselves, is simply (depending on dialect) ''Nde, Ne, Néndé, Héndé'', ''Hen-de'' or ''õne'' ("The People, Men", "the People of"); they never called themselves ″Apaches". The Chiricahua referred to outsiders, such as Americans, Mexicans or other Indians, as ''Enee'', ''ⁿdáa'' or ''Indah / N'daa''. This word has two possible meanings, the first being "strange people, non-Apache people" or "enemy", but another being "eye". Sometimes it is said that all Apaches referred to the Americans and European settlers (with exception of the Mexicans) as ''Bi'ndah-Li'ghi' / Bi'nda-li'ghi'o'yi'' ("White Eyes"), but this seems a name from Mescalero and Lipan Apache bands, as the Chiricahua bands called them ''Daadatlijende'', meaning "Blue/green eye people" or ''Indaaɫigáí / Indaaɫigánde'' meaning "White skinned or pale colored people" or literally "Strange, non-Apache people, which are white-skinned"). ''Łigáí'' means "it is white" or it can be translate as "it is pale colored". The í on the end usually translates as "the one that is", but in the context of human beings, can mean "the group who are".

Culture and organization

Several loosely affiliated bands of Apache came improperly to be usually known as the Chiricahuas. These included the ''Chokonen'' ( recte: Tsokanende), the ''Chihenne'' (recte: Tchihende), the ''Nednai'' (''Nednhi'') and ''Bedonkohe'' (recte, both of them together: Ndendahe). Today, all are commonly referred to as Chiricahua, but they were not historically a single band nor the same Apache division, being more correctly identified, all together, as "Central Apaches". Many other bands and groups of Apachean language-speakers ranged over eastern Arizona and the American Southwest. The bands that are grouped under the Chiricahua term today had much history together: they intermarried and lived alongside each other, and they also occasionally fought with each other. They formed short-term as well as longer alliances that have caused scholars to classify them as one people. The Apachean groups and the Navajo peoples were part of theAthabaskan

Athabaskan (also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large family of indigenous languages of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, Pacific ...

migration into the North American continent from Asia, across the Bering Strait from Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

. As the people moved south and east into North America, groups splintered off and became differentiated by language and culture over time. Some anthropologists believe that the Lipan Apache

Lipan Apache are a band of Apache, a Southern Athabaskan Indigenous people, who have lived in the Southwest and Southern Plains for centuries. At the time of European and African contact, they lived in New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Texas, and ...

and the Navajo

The Navajo (; British English: Navaho; nv, Diné or ') are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of the Southwestern United States.

With more than 399,494 enrolled tribal members , the Navajo Nation is the largest fe ...

were pushed south and west into what is now New Mexico and Arizona by pressure from other Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, a ...

Indians, such as the Comanche

The Comanche or Nʉmʉnʉʉ ( com, Nʉmʉnʉʉ, "the people") are a Native American tribe from the Southern Plains of the present-day United States. Comanche people today belong to the federally recognized Comanche Nation, headquartered in ...

and Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and e ...

. Among the last of such splits were those that resulted in the formation of the different Apachean bands whom the later Europeans encountered: the southwestern Apache groups and the Navajo. Although both speaking forms of Southern Athabaskan, the Navajo and Apache have become culturally distinct.

The "Chihenne (Tchihende)", "Nednai/Nednhi (Ndendahe)" and "Bedonkohe" intermarried sometimes with Mescalero Bands of New Mexico and Chihuahua and formed alliances with them; therefore their Mescalero kin did know the names of Chiricahua bands and local groups: ''Chíhéõde'' ("The People of Red Ceremonial Paint", "The Red Ceremonial Paint People"), ''Ndé'ndaa'õde / Ndé'ndaaõde'' ("The Apache People (who live among) Enemies") and ''Bidáõ'kaõde / Bidáõ'kahéõde'' ("The People whom We Met", "The People whom We Came Upon"), The Mescalero use the term -õde, -éõde, -néõde, or -héõde ("the people of") instead of the Chiricahua Nde, Ne, Néndé, Héndé, Hen-de or õne ("the people of").

History

The Tsokanende (Chiricahua) Apache division was once led, from the beginning of the 18th century, by chiefs such as Pisago Cabezón, Relles, Posito Moraga, Yrigollen, Tapilá, Teboca, Vívora, Miguel Narbona, Esquinaline, and finallyCochise

Cochise (; Apache: ''Shi-ka-She'' or ''A-da-tli-chi'', lit.: ''having the quality or strength of an oak''; later ''K'uu-ch'ish'' or ''Cheis'', lit. ''oak''; June 8, 1874) was leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokonen and principa ...

(whose name was derived from the Apache word ''Cheis,'' meaning "having the quality of oak") and, after his death, his sons Tahzay and, later, Naiche

Chief Naiche ( ; –1919) was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.Johansen, Bruce E"Naiche (ca. 1857–1919)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' (retrieved 25 Sept 2011 ...

, under the guardianship of Cochise's war chief and brother-in-law Nahilzay, and the independent chiefs Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

, Ulzana, Skinya and Pionsenay; Tchihende (Mimbreño) people was led, during the same period, by chiefs as Juan José Compa, Fuerte also known as Soldado Fiero, Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

, Cuchillo Negro, Delgadito

Atsidi Sani ( nv, ) (c. 1830 – c. 1870 or 1918) was the first known Navajo silversmith.

Background

Little is known of Atsidi Sani. However, it is known that he was born near Wheatfields, Arizona, c. 1830 as part of the Dibelizhini (Black Sheep) ...

, Ponce, Nana, Victorio, Loco, Mangus; Ndendahe (Mogollón and Carrizaleño / Janero) Apache people, in the meanwhile, was led by Mahko and, after him, Mano Mocha, Coleto Amarillo, Luis

Luis is a given name. It is the Spanish form of the originally Germanic name or . Other Iberian Romance languages have comparable forms: (with an accent mark on the i) in Portuguese and Galician, in Aragonese and Catalan, while is archai ...

, Laceres, Felipe, Natiza, and finally Juh

Juh (also known as Ju, Ho, Whoa, and sometimes Who;Kraft, Louis (2000). - ''Gatewood and Geronimo''. - Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. - p.4. - c. 1825 – Sept/Oct 1883) was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndé ...

and ''Goyaałé'' (known to the Americans as Geronimo). After Victorio's death, Nana, Gerónimo, Mangus (youngest Mangas Coloradas' son) and youngest Cochise's son ''Naiche

Chief Naiche ( ; –1919) was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.Johansen, Bruce E"Naiche (ca. 1857–1919)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' (retrieved 25 Sept 2011 ...

'' were the last leaders of the Central Apaches, and their mixed Apache group was the last to continue to resist U.S. government control of the American Southwest

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado ...

.

European-Apache relations

From the beginning of EuropeanAmerican/Apache relations, there was conflict between them, as they competed for land and other resources, and had very different cultures. Their encounters were preceded by more than 100 years of Spanish colonial and Mexican incursions and settlement on the Apache lands. The United States settlers were newcomers to the competition for land and resources in theSouthwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sepa ...

, but they inherited its complex history, and brought their own attitudes with them about American Indians and how to use the land. By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ( es, Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo), officially the Treaty of Peace, Friendship, Limits, and Settlement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States, is the peace treaty that was signed on 2 ...

of 1848, the US took on the responsibility to prevent and punish cross-border incursions by Apache who were raiding in Mexico.

The Apache viewed the United States colonists with ambivalence, and in some cases enlisted them as allies in the early years against the Mexicans. In 1852, the US and some of the Chiricahua signed a treaty, but it had little lasting effect. During the 1850s, American miners and settlers began moving into Chiricahua territory, beginning encroachment that had been renewed in the migration to the Southwest of the previous two decades.

This forced the Apachean people to change their lives as nomads, free on the land. The US Army defeated them and forced them into the confinement of reservation life, on lands ill-suited for subsistence farming, which the US proffered as the model of civilization. Today, the Chiricahua are preserving their culture as much as possible, while forging new relationships with the peoples around them. The Chiricahua are a living and vibrant culture, a part of the greater American whole and yet distinct based on their history and culture.

Hostilities

Although they had lived peaceably with most Americans in theNew Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomin ...

up to about 1860, the Chiricahua became increasingly hostile to American encroachment in the Southwest after a number of provocations had occurred between them.

In 1835, Mexico had placed a bounty on Apache scalps which further inflamed the situation. In 1837 Warm Springs Mimbreños' head chief and famed raider, Soldado Fiero also known as Fuerte was killed by Mexican soldiers of the garrison at Janos (only two days' travel from Santa Rita del Cobre), and his son Cuchillo Negro succeeded him as head chief and went to war against Chihuahua for revenge. In the same 1837, the American John (also known as James) Johnson invited the Coppermine Mimbreños in the Pinos Altos area to trade with his party (near the mines at Santa Rita del Cobre

Santa Rita is a ghost town in Grant County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. The site of Chino copper mine, Santa Rita was located fifteen miles east of Silver City.

History

Copper mining in the area began late in the Spanish colonial period, ...

, New Mexico) and, when they gathered around a blanket on which ''pinole'' (a ground corn flour) had been placed for them, Johnson and his men opened fire on the Chihenne with rifles and a concealed cannon loaded with scrap iron, glass, and a length of chain. They killed about 20 Apache, including the chief Juan José Compá. Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

is said to have witnessed this attack, which inflamed his and other Apache warriors' desires for vengeance for many years; he led the survivors to safety and subsequently, together with Cuchillo Negro, took Mimbreño revenge. The historian Rex W. Strickland argued that the Apache had come to the meeting with their own intentions of attacking Johnson's party, but were taken by surprise. In 1839 scalp-hunter James Kirker

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguati ...

was employed by Robert McKnight to re-open the road to Santa Rita del Cobre.

After the conclusion of the US/Mexican War (1848) and the Gadsden Purchase

The Gadsden Purchase ( es, region=MX, la Venta de La Mesilla "The Sale of La Mesilla") is a region of present-day southern Arizona and southwestern New Mexico that the United States acquired from Mexico by the Treaty of Mesilla, which took effe ...

(1853), Americans began to enter the territory in greater numbers. This increased the opportunities for incidents and misunderstandings. The Apaches, including Mangas Coloradas and Cuchillo Negro, were not at first hostile to the Americans, considering them enemies of their own Mexican enemies.

Cuchillo Negro, with Ponce, Delgadito

Atsidi Sani ( nv, ) (c. 1830 – c. 1870 or 1918) was the first known Navajo silversmith.

Background

Little is known of Atsidi Sani. However, it is known that he was born near Wheatfields, Arizona, c. 1830 as part of the Dibelizhini (Black Sheep) ...

, Victorio and other Mimbreño chiefs, signed a treaty at Fort Webster in April 1853, but, during the spring of 1857 the U.S. Army set out on a campaign, led by Col. Benjamin L.E. deBonneville, Col. Dixon S. Miles (3° Cavalry from Fort Thorn) and Col. William W. Loring (commanding a Mounted Rifles Regiment from Albuquerque), against Mogollon and Coyotero Apaches: Loring's Pueblo Indian scouts found out and attacked an Apache rancheria in the Canyon de Los Muertos Carneros (May 25, 1857), where Cuchillo Negro and some Mimbreño Apache were resting after a raid against the Navahos. Some Apaches, including Cuchillo Negro himself, were killed.

In December 1860, after several bad incidents provoked by the miners led by James H. Tevis in the Pinos Altos area, ''Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

'' went to Pinos Altos, New Mexico

Pinos Altos is a census-designated place in Grant County, New Mexico, United States. The community was a mining town, formed in 1860 following the discovery of gold in the nearby Pinos Altos Mountains. The town site is located about five to ten m ...

to try to convince the miners to move away from the area he loved and to go to the Sierra Madre and seek gold there, but they tied him to a tree and whipped him badly. His Mimbreño and Ndendahe followers and related Chiricahua bands were incensed by the treatment of their respected chief. Mangas had been just as great a chief in his prime (during the 1830s and 1840s), along with Cuchillo Negro, as Cochise was then becoming.

In 1861, the US Army seized and killed some of Cochise's relatives near Apache Pass, in what became known as the Bascom Affair. Remembering how Cochise had escaped, the Chiricahua called the incident "cut the tent." In 1863, Gen. James H. Carleton set out leading a new campaign against the Mescalero Apache, and Capt. Edmund Shirland (10° California Cavalry) invited Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

for a "parley" but, after he entered the U.S. camp to negotiate a peace, the great Mimbreño chief was arrested and convicted in Fort McLane

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

, where, probably on Gen. Joseph R. West's orders, Mangas Coloradas was killed by American soldiers (Jan. 18, 1863). His body was mutilated by the soldiers, and his people were enraged by his murder. The Chiricahuas began to consider the Americans as "enemies we go against them." From that time, they waged almost constant war against US settlers and the Army for the next 23 years. Cochise

Cochise (; Apache: ''Shi-ka-She'' or ''A-da-tli-chi'', lit.: ''having the quality or strength of an oak''; later ''K'uu-ch'ish'' or ''Cheis'', lit. ''oak''; June 8, 1874) was leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokonen and principa ...

, his brother-in-law Nahilzay (war chief of Cochise's people), Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

, Skinya, Pionsenay, Ulzana and other warring chiefs became a nightmare to settlers and military garrisons and patrols. In the meantime, the great Victorio, Delgadito

Atsidi Sani ( nv, ) (c. 1830 – c. 1870 or 1918) was the first known Navajo silversmith.

Background

Little is known of Atsidi Sani. However, it is known that he was born near Wheatfields, Arizona, c. 1830 as part of the Dibelizhini (Black Sheep) ...

(soon killed in 1864), Nana, Loco, young Mangus (last son of Mangas Coloradas) and other minor chiefs led on the warpath the Mimbreños, Chiricahuas' cousins and allies, and Juh

Juh (also known as Ju, Ho, Whoa, and sometimes Who;Kraft, Louis (2000). - ''Gatewood and Geronimo''. - Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. - p.4. - c. 1825 – Sept/Oct 1883) was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndé ...

led the Ndendahe (Nednhi and Bedonkohe together).

In 1872, General Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard lost his right arm while leading his men against ...

, with the help of Thomas Jeffords, succeeded in negotiating a peace with Cochise

Cochise (; Apache: ''Shi-ka-She'' or ''A-da-tli-chi'', lit.: ''having the quality or strength of an oak''; later ''K'uu-ch'ish'' or ''Cheis'', lit. ''oak''; June 8, 1874) was leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokonen and principa ...

. The US established a Chiricahua Apache Reservation with Jeffords as US Agent, near Fort Bowie

Fort Bowie was a 19th-century outpost of the United States Army located in southeastern Arizona near the present day town of Willcox, Arizona. The remaining buildings and site are now protected as Fort Bowie National Historic Site.

Fort Bowi ...

, Arizona Territory. It remained open for about 4 years, during which the chief Cochise died (from natural causes). In 1876, about two years after Cochise's death, the US moved the Chiricahua and some other Apache bands to the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation ( Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed f ...

, still in Arizona. This was in response to public outcry after the killings of Orizoba Spence and Nicholas Rogers at Sulpher Springs. The mountain people

Hill people, also referred to as mountain people, is a general term for people who live in the hills and mountains.

This includes all rugged land above and all land (including plateaus) above elevation.

The climate is generally harsh, with s ...

hated the desert environment of San Carlos, and some frequently began to leave the reservation and sometimes raided neighboring settlers.

They surrendered to General Nelson Miles in 1886. The best-known warrior leader of the "renegades", although he was not considered a 'chief', was the forceful and influential Geronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaałé, , ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache b ...

. He and ''Naiche

Chief Naiche ( ; –1919) was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.Johansen, Bruce E"Naiche (ca. 1857–1919)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' (retrieved 25 Sept 2011 ...

'' (the son of Cochise and hereditary leader after Tahzay's death) together led many of the resisters during those last few years of freedom.

Chiricahua Mountains

The Chiricahua Mountains massif is a large mountain range in southeastern Arizona which is part of the Basin and Range province of the west and southwestern United States and northwest Mexico; the range is part of the Coronado National Forest. ...

, part of which is now inside Chiricahua National Monument

Chiricahua National Monument is a unit of the National Park System located in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona. The monument was established on April 18, 1924, to protect its extensive hoodoos and balancing rocks. The Faraway Ra ...

, and across the intervening Willcox Playa to the northeast, in the Dragoon Mountains (all in southeastern Arizona). In late frontier times, the Chiricahua ranged from San Carlos and the White Mountains of Arizona, to the adjacent mountains of southwestern New Mexico around what is now Silver City, and down into the mountain sanctuaries of the Sierra Madre (of northern Mexico). There they often joined with their ''Nednai'' Apache kin.

General George Crook

George R. Crook (September 8, 1828 – March 21, 1890) was a career United States Army officer, most noted for his distinguished service during the American Civil War and the Indian Wars. During the 1880s, the Apache nicknamed Crook ''Nanta ...

, then General Miles' troops, aided by Apache scouts from other groups, pursued the exiles until they gave up. Mexico and the United States had negotiated an agreement allowing their troops in pursuit of the Apache to continue into each other's territories. This prevented the Chiricahua groups from using the border as an escape route, and as they could gain little time to rest and consider their next move, the fatigue, attrition and demoralization of the constant hunt led to their surrender.

The final 34 hold-outs, including Geronimo and Naiche, surrendered to units of General Miles' forces in September 1886. From Bowie Station, Arizona, they were entrained, along with most of the other remaining Chiricahua (as well as the Army's Apache scouts), and exiled to Fort Marion

The Castillo de San Marcos ( Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

, Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and ...

. At least two Apache warriors, Massai

Massai (also known as: Masai, Massey, Massi, Mah–sii, Massa, Wasse, Wassil or by the nickname "Big Foot" Massai; c. 1847–1906, 1911?Simmons, Marc. - "TRAIL DUST: Massai's escape part of Apache history". - ''The Santa Fe New Mexican''. - Nov ...

and Gray Lizard, escaped from their prison car and made their way back to San Carlos Arizona in a journey to their ancestral lands.

After a number of Chiricahua deaths at the Fort Marion

The Castillo de San Marcos ( Spanish for "St. Mark's Castle") is the oldest masonry fort in the continental United States; it is located on the western shore of Matanzas Bay in the city of St. Augustine, Florida.

It was designed by the Spanish ...

prison near St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine ( ; es, San Agustín ) is a city in the Southeastern United States and the county seat of St. Johns County on the Atlantic coast of northeastern Florida. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, it is the oldest continuously inhabi ...

, the survivors were moved, first to Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = " Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,7 ...

, and later to Fort Sill, Oklahoma

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (136.8 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost .

The fort was first built during the Indian Wars. It is designated as a National Historic Landma ...

. Geronimo's surrender ended the Indian Wars in the United States. However, another group of Chiricahua (also known as the ''Nameless Ones'' or ''Bronco Apache'') were not captured by U.S. forces and refused to surrender. They escaped over the border to Mexico, and settled in the remote Sierra Madre mountains. There they built hidden camps, raided homes for cattle and other food supplies, and engaged in periodic firefights with units of the Mexican Army and police. Most were eventually captured or killed by soldiers or by private ranchers armed and deputized by the Mexican government.

Eventually, the surviving Chiricahua prisoners were moved to the Fort Sill

Fort Sill is a United States Army post north of Lawton, Oklahoma, about 85 miles (136.8 km) southwest of Oklahoma City. It covers almost .

The fort was first built during the Indian Wars. It is designated as a National Historic Landmark ...

military reservation in Oklahoma. In August 1912, by an act of the U.S. Congress, they were released from their prisoner of war status as they were thought to be no further threat. Although promised land at Fort Sill, they met resistance from local non-Apache. They were given the choice to remain at Fort Sill or to relocate to the Mescalero reservation near Ruidoso, New Mexico. Two-thirds of the group, 183 people, elected to go to New Mexico, while 78 remained in Oklahoma. Their descendants still reside in these places. At the time, they were not permitted to return to Arizona because of hostility from the long wars.

in 1912 many different Apache bands returned to San Carlos Apache lands after their release from Fort Sill Apache Reservation.

Bands

In the Chiricahua culture, the "band" as a unit was much more important than the

American or European concept of "tribe". The Chiricahua had no name for themselves (autonym) as a people. The name Chiricahua is most likely the Spanish rendering of the

In the Chiricahua culture, the "band" as a unit was much more important than the

American or European concept of "tribe". The Chiricahua had no name for themselves (autonym) as a people. The name Chiricahua is most likely the Spanish rendering of the Opata

The Opata (written Ópata in Spanish, pronounced with stress on the first syllable: /ˈopata/) are three indigenous peoples of Mexico. Opata territory, the “Opatería” in Spanish, encompasses the mountainous northeast and central part of the ...

word ''Chihuicahui or Chiguicagui'' ('mountain of the wild turkey') for the Chiricahua Mountains

The Chiricahua Mountains massif is a large mountain range in southeastern Arizona which is part of the Basin and Range province of the west and southwestern United States and northwest Mexico; the range is part of the Coronado National Forest. ...

, later corrupted into Chiricahui/Chiricahua. The Chiricahua tribal territory encompassed today's SE Arizona, SW New Mexico, NE Sonora and NW Chihuahua. The Chiricahua range extended to the east as far as the Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico and to the west as far as the San Pedro River Valley in Arizona, north of Magdalena just below present day Hwy I-40 corridor in New Mexico and with the town Ciudad Madera (276 km northwest of the state capital, Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

, and 536 km southwest of Ciudad Juárez

Ciudad Juárez ( ; ''Juarez City''. ) is the most populous city in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. It is commonly referred to as Juárez and was known as El Paso del Norte (''The Pass of the North'') until 1888. Juárez is the seat of the Ju� ...

(formerly known as Paso del Norte) on the Mexico–United States border

The Mexico–United States border ( es, frontera Estados Unidos–México) is an international border separating Mexico and the United States, extending from the Pacific Ocean in the west to the Gulf of Mexico in the east. The border trave ...

), as their southernmost range.

According to Morris E. Opler

Morris Edward Opler (May 3, 1907 – May 13, 1996), American anthropologist and advocate of Japanese American civil rights, was born in Buffalo, New York. He was the brother of Marvin Opler, an anthropologist and social psychiatrist.

Morris Ople ...

(1941), the Chiricahuas consisted of three bands:

* Chíhéne or Chííhénee’ 'Red Paint People' (also known as Eastern Chiricahua, Warm Springs Apache, ''Gileños'', '' Ojo Caliente'' Apache, Coppermine Apache, Copper Mine, ''Mimbreños'', ''Mimbres'', Mogollones, Tcihende),

* Ch'úk'ánéń or Ch'uuk'anén ‘Ridge of the Mountainside People’ (also known as Central Chiricahua, ''Ch'ók'ánéń'', Cochise Apache, ''Chiricahua'' proper, Chiricaguis, ''Tcokanene''), or the Sunrise People;

* Ndé'indaaí or Nédnaa'í 'Enemy People' or 'The Apache People (who live among) Enemies' known as the Southern Chiricahua, Pinery Apache, Bronco Apache, ''Ne'na'i''), or "those ahead at the end".

Schroeder (1947) lists five bands:

* Mogollon

* Copper Mine

* Mimbres

* Warm Spring

* Chiricahua proper

The Chiricahua-Warm Springs Fort Sill Apache tribe in Oklahoma say they have four bands in Fort Sill: (some of the Arizona Apaches did not return to San Carlos or Fort Apache, White Mountain Apache warrior Eyelash is buried in Fort Sill cememtry, Southern Tonto Apache Chief/Scout Hosay is buried in Fort Apache cememtery, Hosay has family in Fort Sill and San Carlos today)

* Chíhéne (recte ''Tchi-he-nde'', more correctly known as the Warm Springs and Coppermine Mimbreño bands, ''Chinde''),

* Chukunen (recte ''Tsoka-ne-nde'', also known as the Chiricahua band, Chokonende),

* Bidánku (recte ''Bedonkohe Ndendahe'', also known as Bidanku, Bronco),

* Ndéndai (recte ''Nednhi Ndendahe'', also known as Ndénai, Nednai).

Today they use the word Chidikáágu (derived from the Spanish word ''Chiricahua'') to refer to the Chiricahua in general, and the word Indé, to refer to the Apache in general.

Other sources list these and additional bands (only the Chokonen and Chihuicahui local groups of the Chokonen band were considered by Chiricahua tribal members to be ''the real Chiricahua people''):

* Chokonen, Chukunende or Tsokanende (also known as ''Ch’ók’ánéń, Tsoka-ne-nde, Tcokanene, Chu-ku-nde, Chukunen, Ch’úk’ánéń, Ch’uuk’anén, Chuukonende'' or ''Ch'úk'ânéõne'' – ‘Ridge of the Mountainside People’, ''proper'' or Central Chiricahua)

** Chokonen local group (lived west of Safford, Arizona, along the upper reaches of the Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of ...

, along the San Francisco River in the north to the Mogollon Mountains

The Mogollon Mountains or Mogollon Range ( or ) are a mountain range in Grant County and Catron County of southwestern New Mexico, in the Southwestern United States. They are primarily protected within the Gila National Forest.

Geography

The Mo ...

in New Mexico in the east and the San Simon Valley

The San Simon Valley is a broad valley east of the Chiricahua Mountains, in the northeast corner of Cochise County, Arizona and southeastern Graham County, with a small portion near Antelope Pass in Hidalgo County of southwestern New Mexico. T ...

to the southwest, northeastern local group – headed by Chief Chihuahua (Kla-esh) and his segundo (war chief) and brother Ulzana)

** Chihuicahui group (lived in SE Arizona in the Huachuca Mountains

The Huachuca Mountains are part of the Sierra Vista Ranger District of the Coronado National Forest in Cochise County in southeastern Arizona, approximately south-southeast of Tucson and southwest of the city of Sierra Vista. Included in this a ...

("Wa-CHOO-ka" Mountains; Apache name meaning "thunder mountain") west of the San Pedro River, in the northwest along a line of today's Benson, Johnson, Willcox, and north along the San Simon River to east of SW New Mexico, controlled the southern Pinaleño, Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

, Dos Cabezas, Chiricahua, Dragoon and Mule Mountains

The Mule Mountains are a north/south running mountain range located in the south-central area of Cochise County, Arizona. The highest peak, Mount Ballard, rises to . Prior to mining operations commencing there, the mountains were heavily fo ...

, also known as ''Huachuca Mountains Apache'' or by the Apache name ''Shaiahene'' ("Western People", "Sunset People"), southwestern local group – headed by Cochise (Kùù'chish) (" akood") and after him by his sons, therefore known as ''Chishhéõne'' ("The People of Wood", "The Wood People") or ''Cochise Apache''.)

*** Cai-a-he-ne local group (′Sun Goes Down People, i.e. People of the West′, were the westernmost of all Chihuicahui, western local group)

*** Tse-ga-ta-hen-de / Tséghát'ahéõne local group (′Rock Pocket People′, 'The People beside the Rocks', 'The People on the side of the Rocks', lived in the Chiricahua Mountains

The Chiricahua Mountains massif is a large mountain range in southeastern Arizona which is part of the Basin and Range province of the west and southwestern United States and northwest Mexico; the range is part of the Coronado National Forest. ...

)

*** Dzil-dun-as-le-n / Tsétáguãgáõne local group (′Rocks at Foot of Grass-Expanse′, 'The People of the Plains among the Rocks', 'The People of Rocky Plains', 'The People among White Rocks', lived in the Dragoon Mountains – according to Christian Naiche Jr. this was Cochise's local group.)

** Dzilmora local group (in SW New Mexico in the Alamo Hueco, Little Hatchet and in the Big Hatchet Mountains (which were known to the Apache as ''Dzilmora''), southeastern local group)

** Animas local group (lived south of the Rio Gila, and west of the San Simon Valley in the Peloncillo Mountains (called by Apache ''Dziltilcil'' – "Black Mountain") along the Arizona–New Mexico border south to the Guadalupe Canyon and eastward in the Animas Valley

The Animas Valley is a lengthy and narrow, north–south long, valley located in western Hidalgo County, New Mexico in the Bootheel Region; the extreme south of the valley lies in Sonora- Chihuahua, in the extreme northwest of the Chihuahuan Des ...

and Animas Mountains

The Animas Mountains are a small mountain range in Hidalgo County, within the " Boot-Heel" region of far southwestern New Mexico, in the United States. They extend north–south for about 30 miles (50 km) along the Continental Divide,Since ...

in SW New Mexico, ''southern local group'')

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived in NE Sonora and adjacent Arizona, in Guadalupe Canyon, along the San Bernardino River, northwestern parts of the Sierra San Luis

The Sierra San Luis range is a mountain range in northwest Chihuahua, northeast Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental cordillera. The region contains sky island mountain ranges, called the Madrean Sky Islands, s ...

, in the Batepito Valley with the Sierra Pitaycachi, east of Fronteras

Fronteras is the seat of Fronteras Municipality in the northeastern part of the Mexican state of Sonora. Frontera translates as Border. The elevation is 1,120 meters and neighboring municipalities are Agua Prieta, Nacozari and Bacoachi. The ar ...

, as their stronghold)

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived east of Fronteras in der Sierra Pilares de Teras in Sonora)

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived in the Sierra de los Ajos northeast of the Sonora River

Río Sonora (''Sonora River'') is a 402-kilometer-long river of Mexico. It lies on the Pacific slope of the Mexican state of Sonora and it runs into the Gulf of California.

Watershed

The Sonora River watershed covers of public land. Slopes range ...

, along the Bavispe River towards Fronteras in the north)

* Bedonkohe, Bidánku or Bidankande (''Bi-dan-ku'' – 'In Front of the End People', ''Bi-da-a-naka-enda'' or ''Bedonkohe Ndendahe'' – 'Standing in front of the enemy', lived in West New Mexico between the San Francisco River in the West and the Gila River

The Gila River (; O'odham ima Keli Akimel or simply Akimel, Quechan: Haa Siʼil, Maricopa language: Xiil) is a tributary of the Colorado River flowing through New Mexico and Arizona in the United States. The river drains an arid watershed of ...

to the southeast, lived in the Tularosa Mountains and in their stronghold, the Mogollon Mountains

The Mogollon Mountains or Mogollon Range ( or ) are a mountain range in Grant County and Catron County of southwestern New Mexico, in the Southwestern United States. They are primarily protected within the Gila National Forest.

Geography

The Mo ...

, therefore often called ''Mogollon Apaches'', were also known – together with other Apache local groups living along the Gila River and in the Gila Mountains – as ''Gileños / Gila Apaches'', Northeastern Chiricahua – Geronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaałé, , ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache b ...

, a prominent leader and medicine man (but not a chief) belonged to this band)

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived in the Mogollon Mountains)

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived also in the Mogollon Mountains)

** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived in the Tularosa Mountains)

* Chihenne, Chihende or Tchihende (also known as ''Chi-he-nde, Tci-he-nde, Chíhéne, Chííhénee’, Chiende'' – 'Red Painted People', their autonym could relate to the mineral red coloration of the copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

-containing tribal area, often called ''Copper Mine, Ojo Caliente / Warm Springs, Mimbreños / Mimbres'' and ''Gileños / Gila Apaches'', improperly Eastern Chiricahua)

** Warm Springs Apache (The vicinity of a southern New Mexico hot spring known as Ojo Caliente (Spanish for Hot Spring) was their favourite retreat and was known to the Apache as ''Tih-go-tel'' – ′four broad plains′)

*** northern Warm Springs local group (lived in the northeast of the Bedonkohe in the Datil, Magdalena and Socorro Mountains, the Plains of San Agustin

The Plains of San Agustin (sometimes listed as the Plains of San Augustin) is a region in the southwestern U.S. state of New Mexico in the San Agustin Basin, south of U.S. Highway 60. The area spans Catron and Socorro Counties, about 50 miles ...

, and from today's Quemado east toward the Rio Grande

The Rio Grande ( and ), known in Mexico as the Río Bravo del Norte or simply the Río Bravo, is one of the principal rivers (along with the Colorado River) in the southwestern United States and in northern Mexico.

The length of the Rio G ...

, northern local group – headed by Victorio)

*** southern Warm Springs local group (Warm Springs proper, settled around a warm spring known as Ojo Caliente near present-day Monticello, New Mexico along the Cañada Alamosa, between the Cuchillo Negro Creek and the Animas Creek, controlled the San Mateo as well as the Black Range

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

(Dził Diłhił) west of the Rio Grande to the Rio Gila, used the warm springs in the vicinity of Truth or Consequences

''Truth or Consequences'' is an American game show originally hosted on NBC radio by Ralph Edwards (1940–1957) and later on television by Edwards (1950–1954), Jack Bailey (1954–1956), Bob Barker (1956–1975), Steve Dunne (1957–1958), ...

hence called Warm Springs or Ojo Caliente Apaches, southern local group – headed by Cuchillo Negro)

** Gileños / Gila Apache (often used as a collective name for different Apache groups living along the Gila River; sometimes for all Chiricahua local groups and sometimes for the Aravaipa / Arivaipa Apache and Pinaleño / Pinal Apache of the Western Apache)

*** Ne-be-ke-yen-de local group (′Country of People′ or ′Earth They Own It People′, presumably a mixed Chihenne-Bedonkohe local group, lived southwest of the Gila River, centered around the Santa Lucia Springs in the Little Burro and Big Burro Mountains, controlled the Pinos Altos Mountains, Pyramid Mountains and the vicinity of Santa Rita del Cobre

Santa Rita is a ghost town in Grant County in the U.S. state of New Mexico. The site of Chino copper mine, Santa Rita was located fifteen miles east of Silver City.

History

Copper mining in the area began late in the Spanish colonial period, ...

along the Mimbres River in the east, then called ''Gileños / Gila Apaches'', after discovering profitable copper mines at Santa Rita del Cobre they were called ''Copper Mine Apaches'', western local group – headed by Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

, an Bedonkohe by birth, and later by Loco)

*** Mimbreño / Mimbres local group (lived in southeast-central New Mexico, between the Mimbres River

The Mimbres is a river in southwestern New Mexico.

Course

The Mimbres forms from snowpack and runoff on the southwestern slopes of the Aldo Leopold Wilderness in the Black Range at in Grant County. The river ends in the Guzmán Basin, a smal ...

and the Rio Grande up in the Mimbres Mountains and the Cook's Range, hence called ''Mimbreño / Mimbres Apaches'', eastern local group; often the name Mimbreños is used to identify the whole Chihenne people, sometimes it is just thought of simply as an aggregation of some families belonging to the Chihenne people around the Mimbres Agency established by temporary Indian agent James M. Smith in 1853)

*** local group (today no longer known by name) (lived in southern New Mexico in the Pyramid Mountains and Florida Mountains

The Florida Mountains are a small long, mountain range in New Mexico. The mountains lie in southern Luna County about southeast of Deming, and north of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico; the range lies in the north of the Chihuahuan Desert reg ...

(called by the Chihenne DzilnokoneLong Hanging Mountain) moved to the Rio Grande in the east and south to the Mexican border, southern group)

* Nednhi, Nde’ndai or Ndendahe (also known as ''Ndéndai, Nde-nda-i, Nédnaa’í, Ndé’indaaí, Ndé’indaande, Ndaandénde'' – 'Enemy People', 'People who make trouble', the Mexicans adopted it as ''Bronco Apaches'' – ′Wild, Untamed Apaches′, lived in Sierra Madre Occidental

The Sierra Madre Occidental is a major mountain range system of the North American Cordillera, that runs northwest–southeast through northwestern and western Mexico, and along the Gulf of California. The Sierra Madre is part of the American ...

and desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

s of NW Chihuahua, NO Sonora and SE Arizona, therefore often called ''Sierre Madre Apaches'', Southern Chiricahua)William B. Griffen: ''Apaches at War and Peace: The Janos Presidio 1750–1858'', University of Oklahoma Press 1998,

** Nednhi / Ndendahe Apache (they were subdivided in three local groups)

*** Janeros local group (also known as ''real Nednhi'', lived in NW Chihuahua and NE Sonora, south into the Sierra San Luis

The Sierra San Luis range is a mountain range in northwest Chihuahua, northeast Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental cordillera. The region contains sky island mountain ranges, called the Madrean Sky Islands, s ...

, Sierra del Tigre

Sierra del Tigre is a mountain range in northeastern Sonora, Mexico at the northern region of the Sierra Madre Occidental. The region contains sky island mountain ranges, called the Madrean Sky Islands, some separated from the Sierra Madre Occide ...

, Sierra de Carcay, Sierra de Boca Grande, west beyond the Aros River to Bavispe, east along the Janos River and Casas Grandes River

The Casas Grandes River is a river of Mexico.

See also

*List of rivers of Mexico

References

*Atlas of Mexico, 1975 (http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/atlas_mexico/river_basins.jpg).

*The Prentice Hall American World Atlas, 1984.

*Rand McNally, T ...

toward the Lake Guzmán in the northern part of the Guzmán Basin The Guzmán Basin is an endorheic basin of northern Mexico and the southwestern United States. It occupies the northwestern portion of Chihuahua in Mexico, and extends into southwestern New Mexico in the United States.

Notable rivers of the Guzmán ...

, because they traded at the presidio of Janos they were called ''Janeros Apache'', because they preferred living in the nearly inaccessible Sierra Madre Occidental, their autonym for themselves was ''Dzilthdaklizhénde'' or ''Dził Dklishende'' – ′Blue Mountain People, i.e. People of the Sierra Madre′, northern local group – headed by Juh

Juh (also known as Ju, Ho, Whoa, and sometimes Who;Kraft, Louis (2000). - ''Gatewood and Geronimo''. - Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. - p.4. - c. 1825 – Sept/Oct 1883) was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndé ...

)

*** Tu-ntsa-nde local group (′Big Water People, i.e. People along the Aros River′, their stronghold called ''Guaynopa'' was in the bend of the Papigochic River (Aros River) east of the border of Sonora in the vicinity of a mountain, which called the Apache ''Dzil-da-na-tal'' – ′Mountain Holding Head Up And Peering Out′, smallest local group)

*** Haiahende local group (′People of the Rising Sun, i.e. People of the East′, lived in the Peloncillo Mountains, Animas Mountains and Florida Mountains in SE Arizona and in New Mexico Bootheel

The New Mexico Bootheel is a salient which comprises the southwestern corner of New Mexico. As part of the Gadsden Purchase it is bounded on the east by the Mexican state of Chihuahua along a line at extending south to latitude 31°20′0″N ...

and south into the deserts and mountains of NE of Sonora and the Mexican Plateau

The Central Mexican Plateau, also known as the Mexican Altiplano ( es, Altiplanicie Mexicana), is a large arid-to-semiarid plateau that occupies much of northern and central Mexico. Averaging above sea level, it extends from the United States b ...

in NW Chihuahua, eastern local group)

*** Hakaye local group (were part of Sierra Madre Mountains of Sonora Mexico)

** Carrizaleños local group (known by other Chiricahua as ''Gol-ga-he-ne'' – ′Open Place People′ or ''Gul-ga-ki'' – ′Prairie Dog People′, lived exclusively in Chihuahua, between the presidio

A presidio ( en, jail, fortification) was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire around between 16th and 18th centuries in areas in condition of their control or influence. The presidios of Spanish Philippines in particular, were cen ...

s of Janos in the west and Carrizal and Lake Santa Maria in the east, south toward Corralitos, Casas Grandes

Casas Grandes (Spanish for ''Great Houses''; also known as Paquimé) is a prehistoric archaeological site in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua. Construction of the site is attributed to the Mogollon culture. Casas Grandes has been design ...

and Agua Nuevas north of Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

, controlled the southern part of the Guzmán Basin, and the mountains along the Casas Grandes, Santa Maria and Carmen River, likely called ''TsebekinéndéStone House People' or 'Rock House People', southeastern group)

** Pinaleños / Pinery local group (lived south of Bavispe, between the Bavispe River and Aros River in NE Sonora and NW Chihuahua, controlled the Sierra Huachinera, Sierra de los Alisos and Sierra Nacori Chico, the mountains had a large stock of Apache Pine foresthence they were called ''Pinaleños / Pinery Apaches'', southwestern local group).

The Chokonen, Chihenne, Nednhi, and Bedonkohe had probably up to three other groups, named respectively after their leaders or homelands. By the end of the 19th century, surviving Apache no longer identified these groups. They may have been wiped out (like the Pinaleño-Nednhi) or had joined more powerful groups. For instance, the remnant of the Carrizaleño-Nedhni camped together with their northern kin, the Janero-Nednhi.

The Carrizaleňo-Nednhi shared overlapping territory in the surroundings of Casas Grandes and Aguas Nuevas with the ''Tsebekinéndé'', a southern Mescalero band (which was often called ''Aguas Nuevas'' by the Spanish). The Spanish referred to the Apache band by the same name of Tsebekinéndé. These two different Apache bands were often confused with each other. (Similar confusion arose over distinguishing the Janeros-Nednhi of the Chiricahua (''Dzilthdaklizhéndé'') and the ''Dzithinahndé'' of the Mescalero.

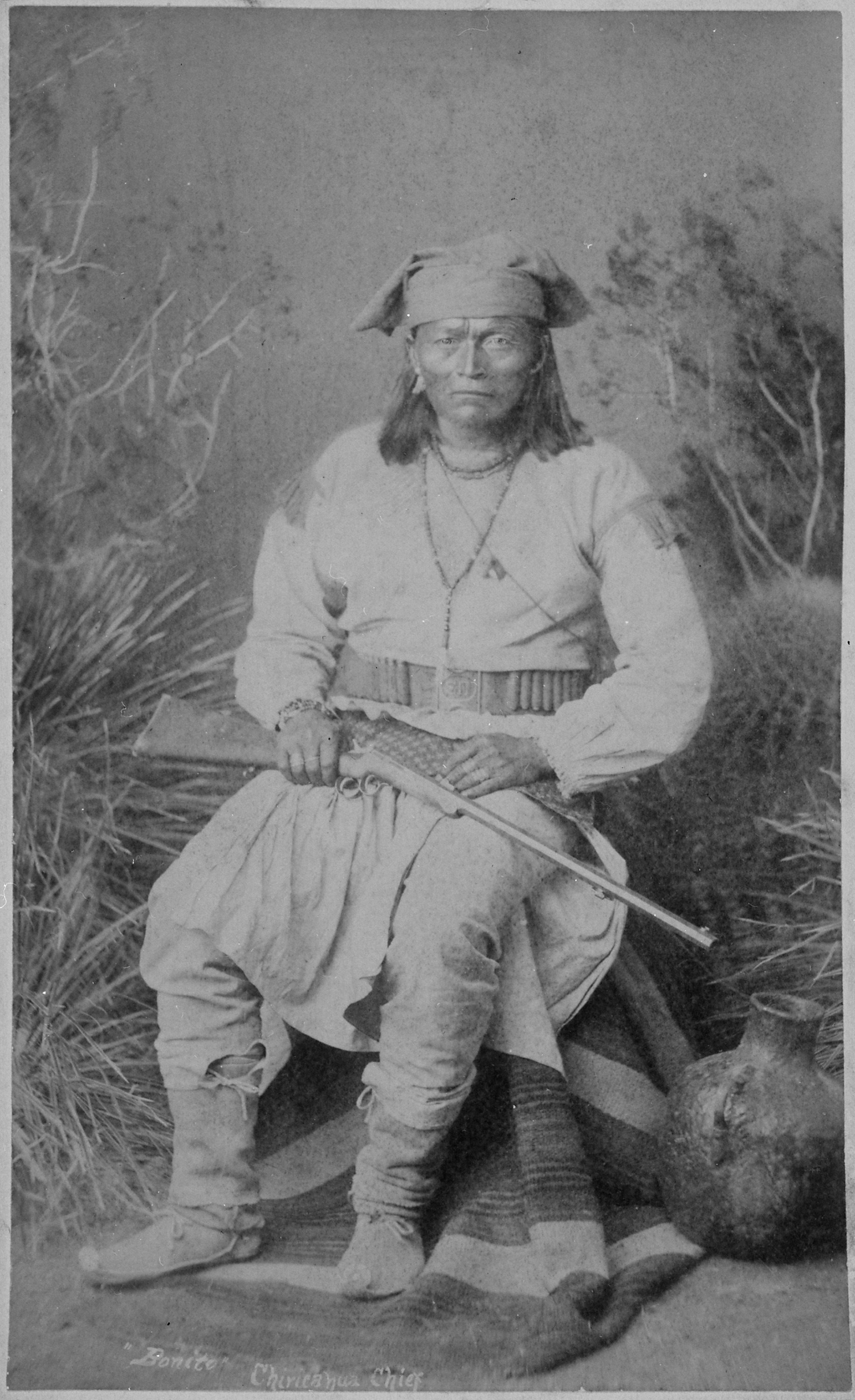

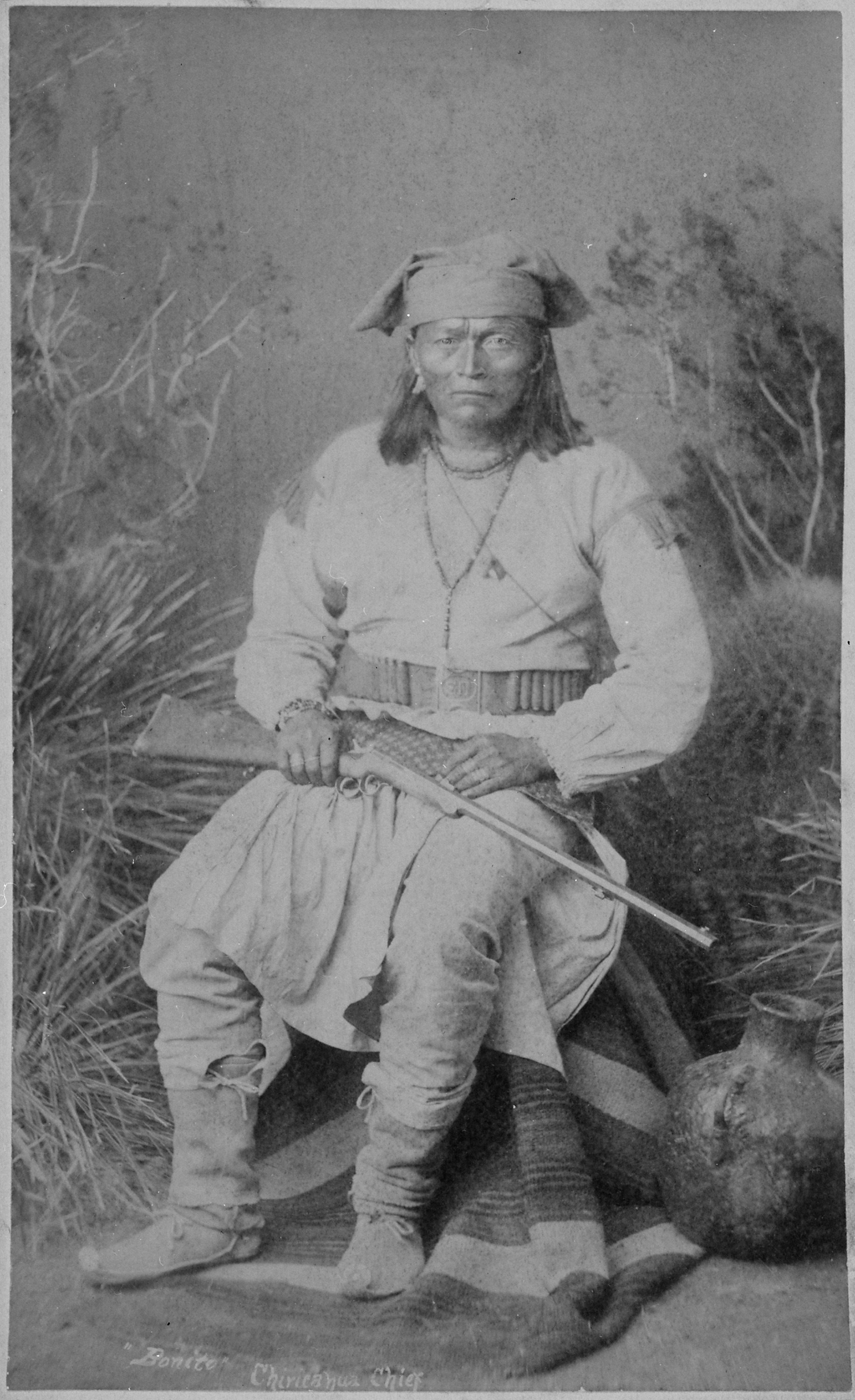

Notable Chiricahua Apache people

Please list 20th and 21st-century people under their specific tribes,Fort Sill Apache Tribe

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.

Government

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is headquartered in Apache, Oklahoma. Tribal member enrollment, which requires a ...

, Mescalero Apache Tribe of the Mescalero Reservation, and San Carlos Apache Tribe

The San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation ( Western Apache: Tsékʼáádn), in southeastern Arizona, United States, was established in 1872 as a reservation for the Chiricahua Apache tribe as well as surrounding Yavapai and Apache bands removed f ...

.

* Geronimo

Geronimo ( apm, Goyaałé, , ; June 16, 1829 – February 17, 1909) was a prominent leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people. From 1850 to 1886, Geronimo joined with members of three other Central Apache b ...

(1829–1909), warrior, medicine man of the Bedonkohe Ndendahe band

* Mildred Cleghorn Mildred Imoch Cleghorn (December 11, 1910 – April 15, 1997) was first chairperson of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe. Her Apache names were ''Eh-Ohn'' and ''Lay-a-Bet'', and she was one of the last Chiricahua Apaches born under "prisoner of war" status ...

(Fort Sill Apache Tribe), served as first tribal chairperson of the Fort Sill Apache Tribe

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is the federally recognized Native American tribe of Chiricahua Warm Springs Apache in Oklahoma.

Government

The Fort Sill Apache Tribe is headquartered in Apache, Oklahoma. Tribal member enrollment, which requires a ...

, elected in 1976

* Chato, also Bidayajislnl or Pedes-klinje (1854–1934), warrior, scout

* Chihuahua Chihuahua may refer to:

Places

* Chihuahua (state), a Mexican state

**Chihuahua (dog), a breed of dog named after the state

**Chihuahua cheese, a type of cheese originating in the state

**Chihuahua City, the capital city of the state

**Chihuahua Mu ...

, also Chewawa, Kla-esh, Tłá’í’ez (ca. 1825–1901)

* Cochise

Cochise (; Apache: ''Shi-ka-She'' or ''A-da-tli-chi'', lit.: ''having the quality or strength of an oak''; later ''K'uu-ch'ish'' or ''Cheis'', lit. ''oak''; June 8, 1874) was leader of the Chihuicahui local group of the Chokonen and principa ...

, chief of the Chihuicahui local group of the Tsokanende people

* Baishan

Baishan (, ko, 백산시) is a prefecture-level city in southeastern Jilin province, in the Dongbei (northeastern) part of China. "" literally means "White Mountain", and is named after Changbai Mountain (, also known as Paektu Mountain (Kor ...

, Cuchillo Negro, (ca. 1796–1857) war chief of the southern Warm Springs local group of the Tchihende people and principal chief of them after Fuerte's / Soldado Fiero's death

* Dahteste (Tahdeste), woman warrior and Lozen's companion; sister of Ilth-goz-ay, the wife of Chihuahua,

* Delgadito

Atsidi Sani ( nv, ) (c. 1830 – c. 1870 or 1918) was the first known Navajo silversmith.

Background

Little is known of Atsidi Sani. However, it is known that he was born near Wheatfields, Arizona, c. 1830 as part of the Dibelizhini (Black Sheep) ...

, (ca. 1810–1864), principal chief of the Copper Mine local group of the Tchihende people

* Gouyen, (ca. 1857–1903), woman from the Warm Springs group of Tchihende people

* Juh

Juh (also known as Ju, Ho, Whoa, and sometimes Who;Kraft, Louis (2000). - ''Gatewood and Geronimo''. - Albuquerque: University of New Mexico. - p.4. - c. 1825 – Sept/Oct 1883) was a warrior and leader of the Janeros local group of the Ndé ...

, (ca. 1825–1883), medicine man and chief of the Janero local group of Nednhi band

* Lozen, "Dextrous Horse Thief" (ca. 1840–1890), woman warrior and prophet of the Tchihende people

* Mangas Coloradas

Mangas Coloradas or Mangus-Colorado (La-choy Ko-kun-noste, alias "Red Sleeve"), or Dasoda-hae ("He Just Sits There") (c. 1793 – January 18, 1863) was an Apache tribal chief and a member of the Mimbreño (Tchihende) division of the Central ...

, (ca. 1793–1863) war chief of the Copper Mines local group of the Tchihende people and principal chief after Juan José Compà's death

* Massai

Massai (also known as: Masai, Massey, Massi, Mah–sii, Massa, Wasse, Wassil or by the nickname "Big Foot" Massai; c. 1847–1906, 1911?Simmons, Marc. - "TRAIL DUST: Massai's escape part of Apache history". - ''The Santa Fe New Mexican''. - Nov ...

, also Mah–sii (ca. 1847–1906/1911), warrior of the Mimbres Tchihende band

* Naiche

Chief Naiche ( ; –1919) was the final hereditary chief of the Chiricahua band of Apache Indians.Johansen, Bruce E"Naiche (ca. 1857–1919)." ''Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.'' (retrieved 25 Sept 2011 ...

(ca. 1857–1919), second son of Cochise, was the final hereditary chief of the Chihuicahui local group of the Tsokanende people

* Nana, (ca. 1805/1810?–1896), war chief of the Warm Springs Tchihende people

* Taza

Taza ( ber, ⵜⴰⵣⴰ, ar, تازة) is a city in northern Morocco occupying the corridor between the Rif mountains and Middle Atlas mountains, about 120 km east of Fez and 150 km west of Al hoceima. It recorded a population of ...

(ca. 1843–1876), son of Cochise and his successor as chief of the Chihuicahui local group of Tsokanende people

* Tso-ay

Tso-ay, also known as Panayotishn or Pe-nel-tishn, today widely known by his nickname as "Peaches", (c. 1853 – December 16, 1933) was a Chiricahua, Western Apache warrior, who also served as a scout for General George Crook during the Apache war ...

, also Panayotishn, Pe-nel-tishn, "Peaches," Scout for General Crook

* Ulzana (ca. 1821–1909), war chief Chihuahua of the Chokonen local group of Tsokanende people

* Victorio, also Bidu-ya, Beduiat (He who checks his horse) (ca. 1825–1880), chief of the Warm Springs Tchihende (Mimbreño) people

See also

*Mescalero-Chiricahua language

Chiricahua (also known as Chiricahua Apache) is a Southern Athabaskan language spoken by the Chiricahua people in Chihuahua and Sonora, México and in Oklahoma and New Mexico. It is related to Navajo and Western Apache and has been described i ...

* Southern Athabaskan languages

Southern Athabaskan (also Apachean) is a subfamily of Athabaskan languages spoken primarily in the Southwestern United States (including Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah) with two outliers in Oklahoma and Texas. The language is spoken to a ...

References

Cited works

* Debo, Angie. (1976) ''Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place,'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. . * Roberts, David. (1993) ''Once They Moved Like the Wind,'' New York: Simon & Schuster. * Thrapp, Dan L. (1988) ''The Conquest of Apacheria,'' Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.Further reading

* Castetter, Edward F. and Opler, Morris E. (1936). ''The ethnobiology of the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache: The use of plants for foods, beverages and narcotics''. Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest, (Vol. 3); Biological series (Vol. 4, No. 5); Bulletin, University of New Mexico, whole, (No. 297). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. * Hoijer, Harry and Opler, Morris E. (1938). ''Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache texts''. The University of Chicago publications in anthropology; Linguistic series. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Reprinted 1964 by Chicago: University of Chicago Press; in 1970 by Chicago: University of Chicago Press; & in 1980 under H. Hoijer by New York: AMS Press, ). * Opler, Morris E. (1933). ''An analysis of Mescalero and Chiricahua Apache social organization in the light of their systems of relationship''. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Chicago. * Opler, Morris E. (1935). The concept of supernatural power among the Chiricahua and Mescalero Apaches. ''American Anthropologist'', ''37'' (1), 65–70. * Opler, Morris E. (1936). The kinship systems of the Southern Athabaskan-speaking tribes. ''American Anthropologist'', ''38'' (4), 620–33. * Opler, Morris E. (1937). An outline of Chiricahua Apache social organization. In F. Egan (Ed.), ''Social anthropology of North American tribes'' (pp. 171–239). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * Opler, Morris E. (1938). A Chiricahua Apache's account of the Geronimo campaign of 1886. ''New Mexico Historical Review'', ''13'' (4), 360–86. * Opler, Morris E. (1941). ''An Apache life-way: The economic, social, and religious institutions of the Chiricahua Indians''. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Reprinted in 1962 by Chicago: University of Chicago Press; in 1965 by New York: Cooper Square Publishers; in 1965 by Chicago: University of Chicago Press; & in 1994 by Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, ). * Opler, Morris E. (1942). The identity of the Apache Mansos. ''American Anthropologist'', ''44'' (1), 725. * Opler, Morris E. (1946). Chiricahua Apache material relating to sorcery. ''Primitive Man'', ''19'' (3–4), 81–92. * Opler, Morris E. (1946). Mountain spirits of the Chiricahua Apache. ''Masterkey'', ''20'' (4), 125–31. * Opler, Morris E. (1947). Notes on Chiricahua Apache culture, I: Supernatural power and the shaman. ''Primitive Man'', ''20'' (1–2), 1–14. * Opler, Morris E. (1983). Chiricahua Apache. In A. Ortiz (Ed.), ''Southwest'' (pp. 401–18). Handbook of North American Indians (Vol. 10). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. * Opler, Morris E.; & French, David H. (1941). ''Myths and tales of the Chiricahua Apache Indians''. Memoirs of the American folk-lore society, (Vol. 37). New York: American Folk-lore Society. (Reprinted in 1969 by New York: Kraus Reprint Co.; in 1970 by New York; in 1976 by Millwood, NY: Kraus Reprint Co.; & in 1994 under M. E. Opler, Morris by Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ). * Opler, Morris E.; & Hoijer, Harry. (1940). The raid and war-path language of the Chiricahua Apache. ''American Anthropologist'', ''42'' (4), 617–34. * Schroeder, Albert H. (1974). ''A study of the Apache Indians: Parts IV and V''. Apache Indians (No. 4), American Indian ethnohistory, Indians of the Southwest. New York: Garland. * Seymour, Deni J. (2002) Conquest and Concealment: After the El Paso Phase on Fort Bliss. Conservation Division, Directorate of Environment, Fort Bliss. Lone Mountain Report 525/528. This document can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. * Seymour, Deni J. (2003) Protohistoric and Early Historic Temporal Resolution. Conservation Division, Directorate of Environment, Fort Bliss. Lone Mountain Report 560–003. This document can be obtained by contacting [email protected]. * Seymour, Deni J. (2003) The Cerro Rojo Complex: A Unique Indigenous Assemblage in the El Paso Area and Its Implications For The Early Apache. Proceedings of the XII Jornada Mogollon Conference in 2001. Geo-Marine, El Paso. * Seymour, Deni J. (2004) A Ranchería in the Gran Apachería: Evidence of Intercultural Interaction at the Cerro Rojo Site. Plains Anthropologist 49(190):153–92. * Seymour, Deni J. (2004) Before the Spanish Chronicles: Early Apache in the Southern Southwest, pp. 120–42. In "Ancient and Historic Lifeways in North America’s Rocky Mountains." Proceedings of the 2003 Rocky Mountain Anthropological Conference, Estes Park, Colorado, edited by Robert H. Brunswig and William B. Butler. Department of Anthropology, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley. * Seymour, Deni J. (2007) Sexually Based War Crimes or Structured Conflict Strategies: An Archaeological Example from the American Southwest. In Texas and Points West: Papers in Honor of John A. Hedrick and Carol P. Hedrick, edited by Regge N. Wiseman, Thomas C. O’Laughlin, and Cordelia T. Snow, pp. 117–34. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico No. 33. Archaeological Society of New Mexico, Albuquerque. * Seymour, Deni J. (2007) Apache, Spanish, and Protohistoric Archaeology on Fort Bliss. Conservation Division, Directorate of Environment, Fort Bliss. Lone Mountain Report 560–005. With Tim Church * Seymour, Deni J. (2007) An Archaeological Perspective on the Hohokam-Pima Continuum. Old Pueblo Archaeology Bulletin No. 51 (December 2007):1–7. (This discusses the early presence of Athapaskans.) * Seymour, Deni J. (2008) Despoblado or Athapaskan Heartland: A Methodological Perspective on Ancestral Apache Landscape Use in the Safford Area. Chapter 5 in Crossroads of the Southwest: Culture, Ethnicity, and Migration in Arizona's Safford Basin, pp. 121–62, edited by David E. Purcell, Cambridge Scholars Press, New York. * Seymour, Deni J. (2008) A Pledge of Peace: Evidence of the Cochise-Howard Treaty Campsite. Historical Archaeology 42(4):154–79. With George Robertson. * Seymour, Deni J. (2008) Apache Plain and Other Plainwares on Apache Sites in the Southern Southwest. In "Serendipity: Papers in Honor of Frances Joan Mathien," edited by R.N. Wiseman, T.C O'Laughlin, C.T. Snow and C. Travis, pp. 163–86. Papers of the Archaeological Society of New Mexico No. 34. Archaeological Society of New Mexico, Albuquerque. * Seymour, Deni J. (2008) Surfing Behind The Wave: A Counterpoint Discussion Relating To "A Ranchería In the Gran Apachería." Plains Anthropologist 53(206):241–62. * Seymour, Deni J. (2008) Pre-Differentiation Athapaskans (Proto-Apache) in the 13th and 14th Century Southern Southwest. Chapter in edited volume under preparation. Also paper in the symposium: The Earliest Athapaskans in Southern Southwest: Implications for Migration, organized and chaired by Deni Seymour, Society for American Archaeology, Vancouver. * Seymour, Deni J. (2009) Evaluating Eyewitness Accounts of Native Peoples along the Coronado Trail from the International Border to Cibola. New Mexico Historical Review 84(3):399–435. * Seymour, Deni J. (2009) Distinctive Places, Suitable Spaces: Conceptualizing Mobile Group Occupational Duration and Landscape Use. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 13(3): 255–81. * Seymour, Deni J. (2009) Nineteenth-Century Apache Wickiups: Historically Documented Models for Archaeological Signatures of the Dwellings of Mobile People. Antiquity 83(319):157–64. * Seymour, Deni J. (2009) Comments On Genetic Data Relating to Athapaskan Migrations: Implications of the Malhi et al. Study for the Apache and Navajo. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 139(3):281–83. * Seymour, Deni J. (2009The Cerro Rojo Site (LA 37188) – A Large Mountain-Top Ancestral Apache Site in Southern New Mexico

Digital History Project. New Mexico Office of the State Historian. * Seymour, Deni J. (2010) Cycles of Renewal, Transportable Assets: Aspects of the Ancestral Apache Housing Landscape. Accepted at Plains Anthropologist. * Seymour, Deni J. (2010) Contextual Incongruities, Statistical Outliers, and Anomalies: Targeting Inconspicuous Occupational Events. American Antiquity. (Winter, in press)

External links

Fort Sill Apache Tribe

official website

Mescalero Apache Tribe

official website

Chiricahua and Mescalero Apache Texts

Allan Houser, Chiricahua Apache artist

National Park Service {{DEFAULTSORT:Chiricahua Apache tribes Chiricahua Mountains History of Catron County, New Mexico Indigenous peoples in Mexico Native American history of Arizona Native American history of New Mexico Native American tribes in Arizona Native American tribes in New Mexico Native American tribes in Oklahoma