Chicago school of political economy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Chicago school of economics is a neoclassical

The term was coined in the 1950s to refer to economists teaching in the Economics Department at the

The term was coined in the 1950s to refer to economists teaching in the Economics Department at the

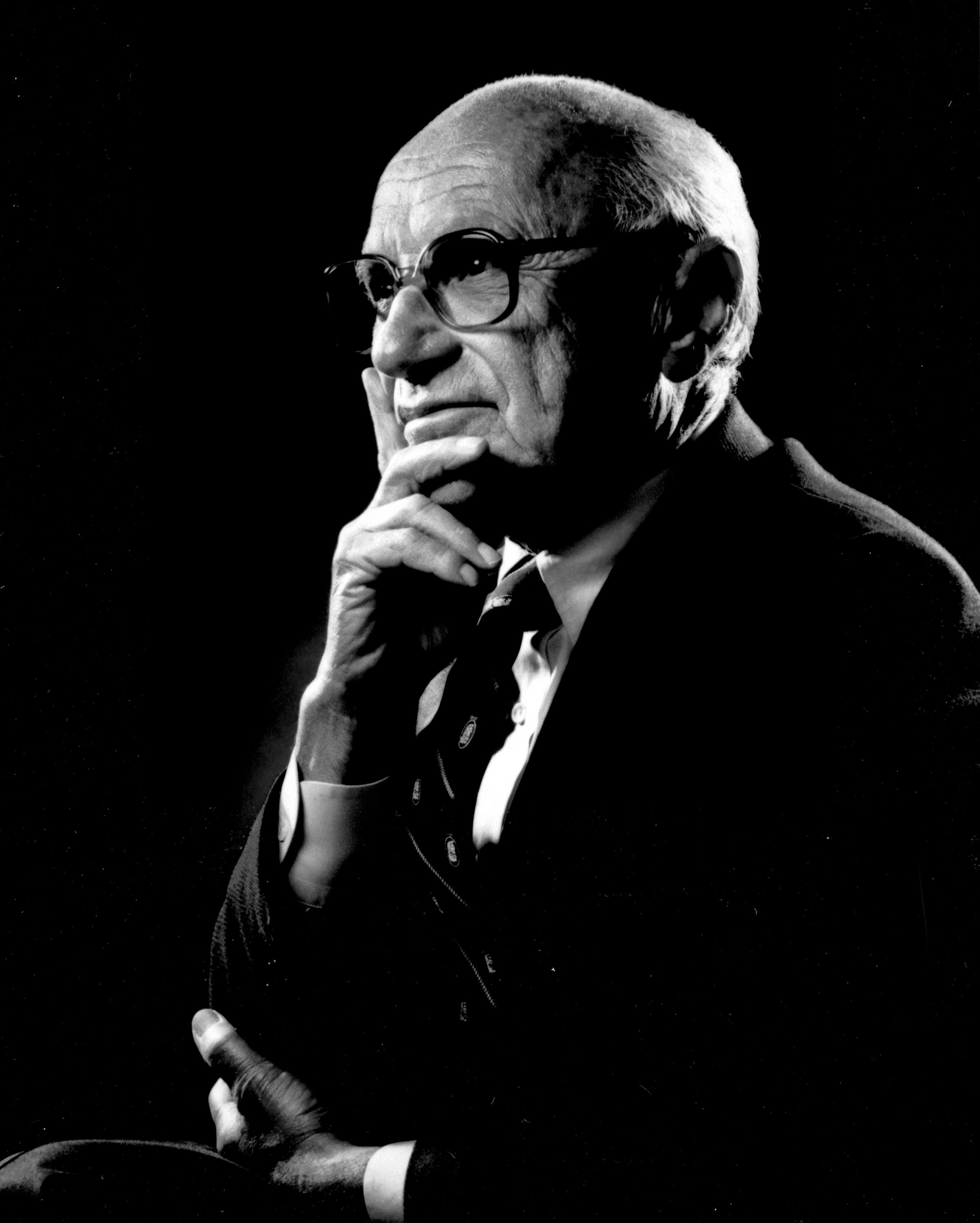

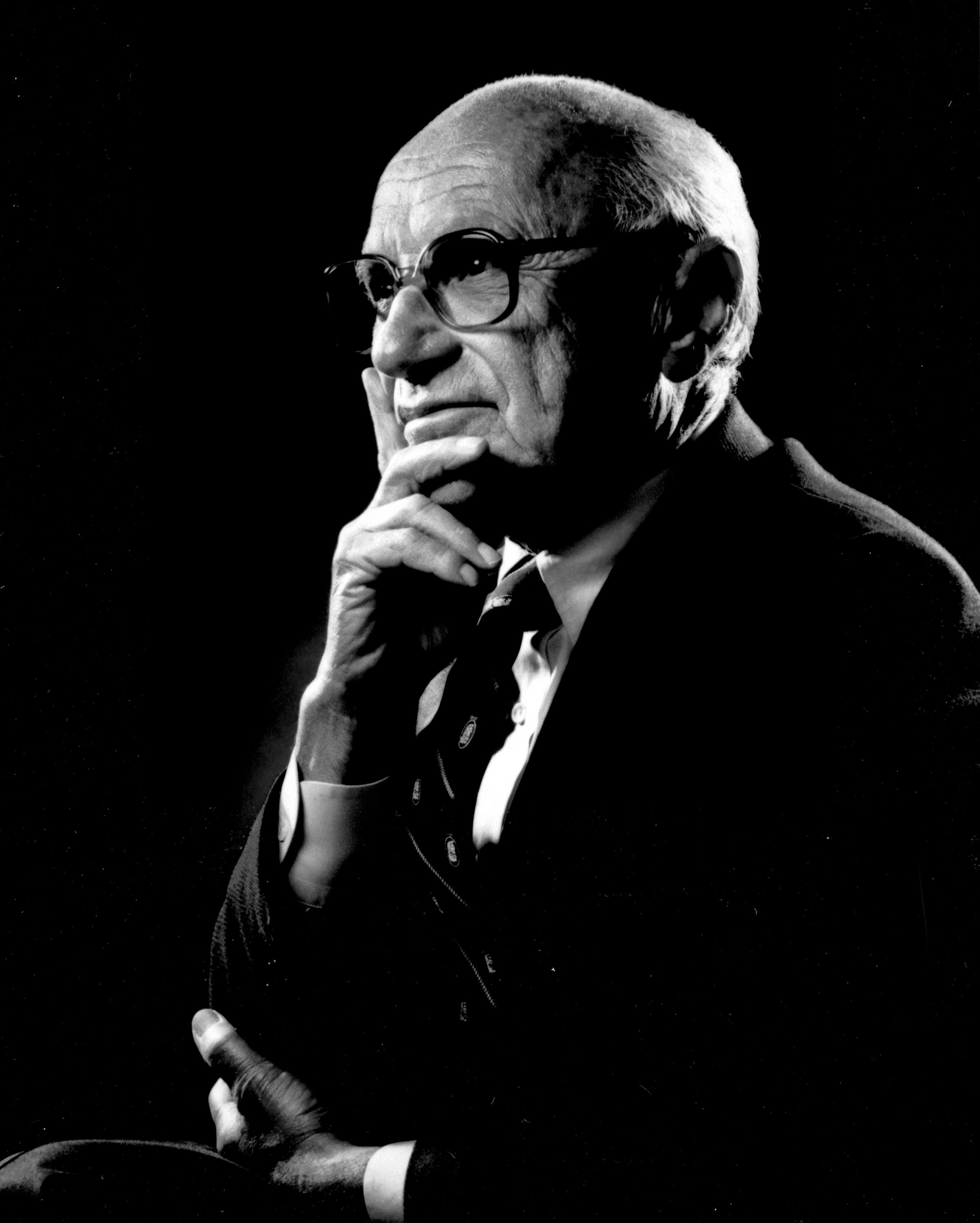

Milton Friedman (1912–2006) stands as one of the most influential economists of the late twentieth century. A student of

Milton Friedman (1912–2006) stands as one of the most influential economists of the late twentieth century. A student of

Eugene Fama (born 1939) is an American financial economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 for his work on empirical asset pricing and is the fourth most highly cited economist of all time. He has spent all of his teaching career at the University of Chicago and is the originator of the efficient-market hypothesis, first defined in his 1965 article as market where "at any point in time, the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value". The notion was further explored in his 1970 article, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work", which brought the notion of efficient markets into the forefront of modern economic theory, and his 1991 article, "Efficient Markets II". Whilst his 1965 Ph.D. thesis, "The Behavior of Stock Market Prices", showed that stock prices can be approximated by a

Eugene Fama (born 1939) is an American financial economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 for his work on empirical asset pricing and is the fourth most highly cited economist of all time. He has spent all of his teaching career at the University of Chicago and is the originator of the efficient-market hypothesis, first defined in his 1965 article as market where "at any point in time, the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value". The notion was further explored in his 1970 article, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work", which brought the notion of efficient markets into the forefront of modern economic theory, and his 1991 article, "Efficient Markets II". Whilst his 1965 Ph.D. thesis, "The Behavior of Stock Market Prices", showed that stock prices can be approximated by a

Richard Posner (born 1939) is known primarily for his work in

Richard Posner (born 1939) is known primarily for his work in

Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) made frequent contacts with many at the University of Chicago during 1940s. His book ''

Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) made frequent contacts with many at the University of Chicago during 1940s. His book ''

World Development Indicators database

Chile's Gini index (measure of income distribution) was 52.0 in 2006, compared to 24.7 of Denmark (most equally distributed) and 74.3 of Namibia (most unequally distributed). Chile has the widest inequality gap of any nation in the

Abstract

* Emmett, Ross B. (2009). Frank Knight and the Chicago school in American economics. Routledge * * * * * Johnson, Marianne. 2020. "''Where Economics Went Wrong'': A Review Essay." Journal of Economic Literature, 58 (3): 749–776. * * McCloskey, Deirdre N. (2010). Bourgeois dignity: Why economics can't explain the modern world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. . * * * * Reprinted in John Cunningham Wood & R.N. Woods (1990), ''Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments'', pp

343–393

* Shils, Edward, ed. (1991). Remembering the University of Chicago: teachers, scientists, and scholars. University of Chicago Press. * *

Description

preview

* *

Thomas Sowell

The University of Chicago Department of Economics

* ttps://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.ECONOMICSDEPT Guide to the University of Chicago Department of Economics Records 1912–1961at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chicago School Of Economics Conservatism in the United States Libertarianism in the United States Schools of economic thought

school of economic thought

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, particularly in moder ...

associated with the work of the faculty at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, some of whom have constructed and popularized its principles. Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

are considered the leading scholars of the Chicago school.

Chicago macroeconomic theory rejected Keynesianism

Keynesian economics ( ; sometimes Keynesianism, named after British economist John Maynard Keynes) are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand (total spending in the economy) strongly influences economic output ...

in favor of monetarism

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on nation ...

until the mid-1970s, when it turned to new classical macroeconomics

New classical macroeconomics, sometimes simply called new classical economics, is a school of thought in macroeconomics that builds its analysis entirely on a neoclassical framework. Specifically, it emphasizes the importance of rigorous founda ...

heavily based on the concept of rational expectations

In economics, "rational expectations" are model-consistent expectations, in that agents inside the model are assumed to "know the model" and on average take the model's predictions as valid. Rational expectations ensure internal consistency i ...

.

The freshwater–saltwater distinction is largely antiquated today, as the two traditions have heavily incorporated ideas from each other. Specifically, new Keynesian economics

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroec ...

was developed as a response to new classical economics, electing to incorporate the insight of rational expectations without giving up the traditional Keynesian focus on imperfect competition In economics, imperfect competition refers to a situation where the characteristics of an economic market do not fulfil all the necessary conditions of a perfectly competitive market. Imperfect competition will cause market inefficiency when it hap ...

and sticky wages.

Chicago economists have also left their intellectual influence in other fields, notably in pioneering public choice theory and law and economics

Law and economics, or economic analysis of law, is the application of microeconomic theory to the analysis of law, which emerged primarily from scholars of the Chicago school of economics. Economic concepts are used to explain the effects of law ...

, which have led to revolutionary changes in the study of political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

and law. Other economists affiliated with Chicago have made their impact in fields as diverse as social economics

Socioeconomics (also known as social economics) is the social science that studies how economic activity affects and is shaped by social processes. In general it analyzes how modern societies progress, stagnate, or regress because of their local ...

and economic history

Economic history is the academic learning of economies or economic events of the past. Research is conducted using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the application of economic theory to historical situations and i ...

. Kaufman (2010) says that the Chicago school can be generally characterized by the following:

As of 2018, the University of Chicago Economics department, considered one of the world's foremost economics departments, has been awarded 14 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences—more than any other university—and has been awarded six John Bates Clark Medal

The John Bates Clark Medal is awarded by the American Economic Association to "that American economist under the age of forty who is adjudged to have made a significant contribution to economic thought and knowledge." The award is named after the ...

s. Not all members of the department belong to the Chicago school of economics, which is a school of thought rather than an organization.

History and terminology

The term was coined in the 1950s to refer to economists teaching in the Economics Department at the

The term was coined in the 1950s to refer to economists teaching in the Economics Department at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, and closely related academic areas at the university such as the Booth School of Business

The University of Chicago Booth School of Business (Chicago Booth or Booth) is the graduate business school of the University of Chicago. Founded in 1898, Chicago Booth is the second-oldest business school in the U.S. and is associated with 10 N ...

, Harris School of Public Policy

The University of Chicago Harris School of Public Policy, also referred to as "Harris Public Policy," is the public policy school of the University of Chicago in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is located on the University's main campus in H ...

and the Law School. In the context of macroeconomics, it is connected to the freshwater school of macroeconomics, in contrast to the saltwater school based in coastal universities (notably Harvard, Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

, Penn, UC Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant uni ...

, and UCLA

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California. UCLA's academic roots were established in 1881 as a teachers college then known as the southern branch of the California ...

).

The Chicago economists met together in frequent intense discussions that helped set a group outlook on economic issues, based on price theory. The 1950s saw the height of popularity of the Keynesian school of economics, so the members of the University of Chicago were considered outside the mainstream.

Besides what is popularly known as the "Chicago school", there is also an "Old Chicago" or the ''first-generation'' Chicago school of economics, consisting of an earlier generation of economists such as Frank Knight

Frank Hyneman Knight (November 7, 1885 – April 15, 1972) was an American economist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago, where he became one of the founders of the Chicago School. Nobel laureates Milton Friedman, George ...

, Henry Simons, Lloyd Mints

Lloyd Wynn Mints (1888–1989) was an American economist, notable for his contributions to the quantity theory of money.

Biography

Born in South Dakota, Lloyd Mints moved with his family in 1888 to Missouri and then in 1901 to Boulder, Colorado. ...

, Jacob Viner

Jacob Viner (3 May 1892 – 12 September 1970) was a Canadian economist and is considered with Frank Knight and Henry Simons to be one of the "inspiring" mentors of the early Chicago school of economics in the 1930s: he was one of the leading fig ...

, Aaron Director

Aaron Director (; September 21, 1901 – September 11, 2004) was a Russian-born American economist and academic who played a central role in the development of the field Law and Economics and the Chicago school of economics. Director was a profe ...

and others. This group had diverse interests and approaches, but Knight, Simons, and Director in particular advocated a focus on the role of incentives and the complexity of economic events rather than on general equilibrium

In economics, general equilibrium theory attempts to explain the behavior of supply, demand, and prices in a whole economy with several or many interacting markets, by seeking to prove that the interaction of demand and supply will result in an ov ...

. Outside of Chicago, these early leaders were important influences on the Virginia school of political economy. Nonetheless, these scholars had an important influence on the thought of Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

and George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

who were the leaders of the ''second-generation'' Chicago school, most notably in the development of price theory

Microeconomics is a branch of mainstream economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics foc ...

and transaction cost

In economics and related disciplines, a transaction cost is a cost in making any economic trade when participating in a market. Oliver E. Williamson defines transaction costs as the costs of running an economic system of companies, and unlike pro ...

economics. The ''third generation'' of Chicago economics is led by Gary Becker

Gary Stanley Becker (; December 2, 1930 – May 3, 2014) was an American economist who received the 1992 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences. He was a professor of economics and sociology at the University of Chicago, and was a leader of ...

, as well as macroeconomists Robert Lucas Jr. and Eugene Fama

Eugene Francis "Gene" Fama (; born February 14, 1939) is an American economist, best known for his empirical work on portfolio theory, asset pricing, and the efficient-market hypothesis.

He is currently Robert R. McCormick Distinguished Servic ...

.

A further significant branching of Chicago thought was dubbed by George Stigler as "Chicago political economy". Inspired by the Coasian view that institutions evolve to maximize the Pareto efficiency

Pareto efficiency or Pareto optimality is a situation where no action or allocation is available that makes one individual better off without making another worse off. The concept is named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923), Italian civil engi ...

, Chicago political economy came to the surprising and controversial view that politics tends towards efficiency and that policy advice is irrelevant.

Awards and honors

Nobel Prizes

As of 2018, the University of Chicago Economics Department has been awarded 14Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

(laureates were affiliated with the department when receiving the prizes) since the prize was first awarded in 1969. In addition, as of October 2018, 32 out of the total 81 Nobel laureates in Economics have been affiliated with the university as alumni, faculty members or researchers. However, not all members of the department belong to the Chicago school of economics.

John Bates Clark Medals

As of 2019, the University of Chicago Economics Department has been awarded 6 John Bates Clark Medals (medalists were affiliated with the department when receiving the medals) since the medal was first awarded in 1947. However, some medalists may ''not'' belong to the Chicago school of economics.Notable scholars

Early members

Frank Knight

Frank Knight (1885–1972) was an early member of the University of Chicago department. He joined the department in 1929, coming from theUniversity of Iowa

The University of Iowa (UI, U of I, UIowa, or simply Iowa) is a public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized into 12 col ...

. His most influential work was ''Risk, Uncertainty and Profit'' (1921) from which the term Knightian uncertainty

In economics, Knightian uncertainty is a lack of any quantifiable knowledge about some possible occurrence, as opposed to the presence of quantifiable risk (e.g., that in statistical noise or a parameter's confidence interval). The concept acknow ...

was derived. Knight's perspective was iconoclastic, and markedly different from later Chicago school thinkers. He believed that while the free market could be inefficient, government programs were even less efficient. He drew from other economic schools of thought such as institutional economics to form his own nuanced perspective.

Henry Simons

Henry Calvert Simons (1899–1946) did his graduate work at the University of Chicago but did not submit his final dissertation to receive a degree. In fact, he was initially influenced by Frank Knight while he was an assistant professor at theUniversity of Iowa

The University of Iowa (UI, U of I, UIowa, or simply Iowa) is a public research university in Iowa City, Iowa, United States. Founded in 1847, it is the oldest and largest university in the state. The University of Iowa is organized into 12 col ...

from 1925 to 1927, and in summer 1927 Simons decided to join the Department of Economics at the University of Chicago (earlier than Knight did). He was a long-term member in the Chicago economics department, most notable for his antitrust and monetarist models.

Jacob Viner

Jacob Viner (1892–1970) was in the faculty of Chicago's economics department for 30 years (1916–1946). He inspired a generation of economists at Chicago, including Milton Friedman.Aaron Director

Aaron Director (1901–2004) had been a professor at Chicago's Law School since 1946. He is regarded as a founder of the fieldLaw and economics

Law and economics, or economic analysis of law, is the application of microeconomic theory to the analysis of law, which emerged primarily from scholars of the Chicago school of economics. Economic concepts are used to explain the effects of law ...

, and established ''The Journal of Law & Economics

''The Journal of Law and Economics'' is an academic journal published by the University of Chicago Press. It publishes articles on the economic analysis of regulation and the behavior of regulated firms, the political economy of legislation and leg ...

'' in 1958''.'' Director influenced some of the next generation of jurists, including Richard Posner

Richard Allen Posner (; born January 11, 1939) is an American jurist and legal scholar who served as a federal appellate judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit from 1981 to 2017. A senior lecturer at the University of Chic ...

, Antonin Scalia and Chief Justice William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

.

Theodore Schultz

A group of agricultural economists led by Theodore Schultz (1902–1998) and D. Gale Johnson (1916–2003) moved from Iowa State to the University of Chicago in the mid-1940s. Schultz served as the chair of economics from 1946 to 1961. He became president of the American Economic Association in 1960, retired in 1967, though he remained active at the University of Chicago until his death in 1998. Johnson served as department chair from 1971 to 1975 and 1980–1984 and was president of the American Economics Association in 1999. Their research in farm and agricultural economics was widely influential and attracted funding from the Rockefeller Foundation to the agricultural economics program at the university. Among the graduate students and faculty affiliated with the pair in the 1940s and 1950s wereClifford Hardin

Clifford Morris Hardin (October 9, 1915April 4, 2010) was an American politician and was the Chancellor of the University of Nebraska. He served as the United States Secretary of Agriculture from 1969 to 1971 under President Richard Nixon.

Biog ...

, Zvi Griliches

Hirsh Zvi Griliches ( ; 12 September 1930 – 4 November 1999) was an economist at Harvard University. The works by Zvi Griliches mostly concerned the economics of technological change, including empirical studies of diffusion of innovations and ...

, Marc Nerlove

Marc Leon Nerlove (born 12 October 1933) is an American agricultural economist and econometrician and a distinguished university professor emeritus in agricultural and resource economics at the University of Maryland. He was awarded the John Bat ...

, and George S. Tolley. In 1979, Schultz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work in human capital theory and economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and ...

.

Second generation

Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (1912–2006) stands as one of the most influential economists of the late twentieth century. A student of

Milton Friedman (1912–2006) stands as one of the most influential economists of the late twentieth century. A student of Frank Knight

Frank Hyneman Knight (November 7, 1885 – April 15, 1972) was an American economist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago, where he became one of the founders of the Chicago School. Nobel laureates Milton Friedman, George ...

, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976 for, among other things, ''A Monetary History of the United States'' (1963). Friedman argued that the Great Depression had been caused by the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

's policies through the 1920s, and worsened in the 1930s. Friedman argued that laissez-faire government policy is more desirable than government intervention in the economy.

Governments should aim for a neutral monetary policy oriented toward long-run economic growth, by gradual expansion of the money supply. He advocated the quantity theory of money

In monetary economics, the quantity theory of money (often abbreviated QTM) is one of the directions of Western economic thought that emerged in the 16th-17th centuries. The QTM states that the general price level of goods and services is directly ...

, that general prices are determined by money. Therefore, active monetary (e.g. easy credit) or fiscal (e.g. tax and spend) policy can have unintended negative effects. In ''Capitalism and Freedom

''Capitalism and Freedom'' is a book by Milton Friedman originally published in 1962 by the University of Chicago Press which discusses the role of economic capitalism in liberal society. It has sold more than half a million copies since 1962 and ...

'' (1992) Friedman wrote:

The slogan that "money matters" has come to be associated with Friedman, but Friedman had also leveled harsh criticism of his ideological opponents. Referring to Thorstein Veblen

Thorstein Bunde Veblen (July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was a Norwegian-American economist and sociologist who, during his lifetime, emerged as a well-known critic of capitalism.

In his best-known book, ''The Theory of the Leisure Class'' ...

's assertion that economics unrealistically models people as "lightning calculator of pleasure and pain", Friedman wrote:

George Stigler

George Stigler (1911–1991) was tutored for his thesis byFrank Knight

Frank Hyneman Knight (November 7, 1885 – April 15, 1972) was an American economist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago, where he became one of the founders of the Chicago School. Nobel laureates Milton Friedman, George ...

and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1982. He is best known for developing the ''Economic Theory of Regulation'', also known as regulatory capture

In politics, regulatory capture (also agency capture and client politics) is a form of corruption of authority that occurs when a political entity, policymaker, or regulator is co-opted to serve the commercial, ideological, or political interests ...

, which says that interest groups and other political participants will use the regulatory and coercive powers of government to shape laws and regulations in a way that is beneficial to them. This theory is an important component of the Public Choice

Public choice, or public choice theory, is "the use of economic tools to deal with traditional problems of political science". Gordon Tullock, 9872008, "public choice," ''The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics''. . Its content includes the s ...

field of economics. He also carried out extensive research into the history of economic thought. His 1962 article "Information in the Labor Market" developed the theory of search unemployment

Frictional unemployment is a form of unemployment reflecting the gap between someone voluntarily leaving a job and finding another. As such, it is sometimes called search unemployment, though it also includes gaps in employment when transferring ...

.

Ronald Coase

Ronald Coase (1910–2013) was the most prominent economic analyst of law and the 1991Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

-winner. His first major article, "The Nature of the Firm

"The Nature of the Firm" (1937) is an article by Ronald Coase. It offered an economic explanation of why individuals choose to form partnerships, companies, and other business entities rather than trading bilaterally through contracts on a market. ...

" (1937), argued that the reason for the existence of firms (companies

A company, abbreviated as co., is a legal entity representing an association of people, whether natural, legal or a mixture of both, with a specific objective. Company members share a common purpose and unite to achieve specific, declared go ...

, partnerships, etc.) is the existence of transaction costs. Rational individuals trade through bilateral contracts on open markets until the costs of transactions mean that using corporations to produce things is more cost-effective.''Sturges v. Bridgman'' (1879) 11 Ch D 852

His second major article, "The Problem of Social Cost

"The Problem of Social Cost" (1960) by Ronald Coase, then a faculty member at the University of Virginia, is an article dealing with the economic problem of externalities. It draws from a number of English legal cases and statutes to illustrate Co ...

" (1960), argued that if we lived in a world without transaction costs, people would bargain with one another to create the same allocation of resources, regardless of the way a court might rule in property disputes. Coase used the example of an 1879 London legal case about nuisance

Nuisance (from archaic ''nocence'', through Fr. ''noisance'', ''nuisance'', from Lat. ''nocere'', "to hurt") is a common law tort. It means that which causes offence, annoyance, trouble or injury. A nuisance can be either public (also "common") ...

named ''Sturges v Bridgman

''Sturges v Bridgman'' (1879) LR 11 Ch D 852 is a landmark case in nuisance decided by the Court of Appeal of England and Wales. It decides that what constitutes reasonable use of one's property depends on the character of the locality and tha ...

'', in which a noisy sweetmaker and a quiet doctor were neighbours; the doctor went to court seeking an injunction against the noise produced by the sweetmaker. Coase said that regardless of whether the judge ruled that the sweetmaker had to stop using his machinery, or that the doctor had to put up with it, they could strike a mutually beneficial bargain that reaches the same outcome of resource distribution. Only the existence of transaction costs may prevent this.

So, the law ought to pre-empt what ''would'' happen, and be guided by the most efficient solution. The idea is that law and regulation are not as important or effective at helping people as lawyers and government planners believe. Coase and others like him wanted a change of approach, to put the burden of proof for positive effects on a government that was intervening in the market, by analysing the costs of action.

Third generation

Gary Becker

Gary Becker (1930–2014) received theNobel Prize in Economics

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

1992 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is the highest civilian award of the United States, along with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is an award bestowed by the president of the United States to recognize people who have made "an especially merit ...

in 2007. Becker received his PhD at the University of Chicago in 1955 under H. Gregg Lewis, and was influenced by Milton Friedman. In 1970, he returned to Chicago as a professor and stayed affiliated with the university until his death. He is considered one of the founding fathers of Chicago political economy, and one of the most influential economists and social scientists in the second half of the twentieth century.

Becker was known in his work for applying economic methods of thinking to other fields, such as crime, sexual relationships, slavery and drugs, assuming that people act rationally. His work was originally focused in labor economics. His work partly inspired the popular economics book ''Freakonomics

''Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything'' is the debut non-fiction book by University of Chicago economist Steven Levitt and ''New York Times'' journalist Stephen J. Dubner. Published on April 12, 2005, by Will ...

''. In June 2011, the Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics

The Gary Becker Milton Friedman Institute for Research in Economics is a collaborative, cross-disciplinary center for research in economics. The institute was established at the University of Chicago in June 2011. It brought together the activit ...

was established at the University of Chicago in honor of Gary Becker and Milton Friedman.

Robert E. Lucas

Robert Lucas (born 1937), who won the Nobel Prize in 1995, has dedicated his life to unwinding Keynesianism. His major contribution is the argument that macroeconomics should not be seen as a separate mode of thought from microeconomics, and that analysis in both should be built on the same foundations. Lucas's works cover several topics in macroeconomics, included economic growth, asset pricing, and monetary economics.Eugene Fama

Eugene Fama (born 1939) is an American financial economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 for his work on empirical asset pricing and is the fourth most highly cited economist of all time. He has spent all of his teaching career at the University of Chicago and is the originator of the efficient-market hypothesis, first defined in his 1965 article as market where "at any point in time, the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value". The notion was further explored in his 1970 article, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work", which brought the notion of efficient markets into the forefront of modern economic theory, and his 1991 article, "Efficient Markets II". Whilst his 1965 Ph.D. thesis, "The Behavior of Stock Market Prices", showed that stock prices can be approximated by a

Eugene Fama (born 1939) is an American financial economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 for his work on empirical asset pricing and is the fourth most highly cited economist of all time. He has spent all of his teaching career at the University of Chicago and is the originator of the efficient-market hypothesis, first defined in his 1965 article as market where "at any point in time, the actual price of a security will be a good estimate of its intrinsic value". The notion was further explored in his 1970 article, "Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work", which brought the notion of efficient markets into the forefront of modern economic theory, and his 1991 article, "Efficient Markets II". Whilst his 1965 Ph.D. thesis, "The Behavior of Stock Market Prices", showed that stock prices can be approximated by a random walk

In mathematics, a random walk is a random process that describes a path that consists of a succession of random steps on some mathematical space.

An elementary example of a random walk is the random walk on the integer number line \mathbb Z ...

in the short-term; in later work he showed that insofar as stock prices are predictable in the long-term, it is largely due to rational time-varying risk premia which can be modelled using the Fama–French three-factor model (1993, 1996) or their updated five-factor model (2014). His work showing that the value premium can persist despite rational forecasts of future earnings and that the performance of actively managed funds is almost entirely due to chance or exposure to risk are all supportive of an efficient-markets view of the world.

Robert Fogel

Robert Fogel (1926–2013), a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in 1993, is well known for his historical analysis and his introduction ofNew economic history

Cliometrics (, also ), sometimes called new economic history or econometric history, is the systematic application of economic theory, econometric techniques, and other formal or mathematical methods to the study of history (especially social and e ...

, and invention of cliometrics

Cliometrics (, also ), sometimes called new economic history or econometric history, is the systematic application of economic theory, econometric techniques, and other formal or mathematical methods to the study of history (especially social and e ...

. In his tract, ''Railroads and American Economic Growth: Essays in Econometric History,'' Fogel set out to rebut comprehensively the idea that railroads contributed to economic growth in the 19th century. Later, in '' Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery'', he argued that slaves in the Southern states of America had a higher standard of living than the industrial proletariat of the Northern states before the American civil war

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.

James Heckman

James Heckman (born 1944) is a Nobel Prize-winner from 2000, is known for his pioneering work in econometrics and microeconomics.Lars Peter Hansen

Lars Peter Hansen (born 1952) is an American economist who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2013 with Eugene Fama and Robert Shiller for their work on asset pricing. Hansen began teaching at the University of Chicago in 1981 and is the David Rockefeller Distinguished Service Professor of economics at the University of Chicago. Although best known for his work on the Generalized method of moments, he is also a distinguished macroeconomist, focusing on the linkages between the financial and real sectors of the economy.Richard Posner

Richard Posner (born 1939) is known primarily for his work in

Richard Posner (born 1939) is known primarily for his work in law and economics

Law and economics, or economic analysis of law, is the application of microeconomic theory to the analysis of law, which emerged primarily from scholars of the Chicago school of economics. Economic concepts are used to explain the effects of law ...

, though Robert Solow

Robert Merton Solow, GCIH (; born August 23, 1924) is an American economist whose work on the theory of economic growth culminated in the exogenous growth model named after him. He is currently Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at the ...

describes Posner's grasp of certain economic ideas as "in some respects,... precarious". A federal appellate judge rather than an economist, Posner's main work, ''Economic Analysis of Law'' attempts to apply rational choice models to areas of law. He has chapters on tort

A tort is a civil wrong that causes a claimant to suffer loss or harm, resulting in legal liability for the person who commits the tortious act. Tort law can be contrasted with criminal law, which deals with criminal wrongs that are punishable ...

, contract, corporations, labor law

Labour laws (also known as labor laws or employment laws) are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, ...

, but also criminal law, discrimination and family law

Family law (also called matrimonial law or the law of domestic relations) is an area of the law that deals with family matters and domestic relations.

Overview

Subjects that commonly fall under a nation's body of family law include:

* Marriage ...

. Posner goes so far as to say that:

Related scholars

Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) made frequent contacts with many at the University of Chicago during 1940s. His book ''

Friedrich Hayek (1899–1992) made frequent contacts with many at the University of Chicago during 1940s. His book ''The Road to Serfdom

''The Road to Serfdom'' ( German: ''Der Weg zur Knechtschaft'') is a book written between 1940 and 1943 by Austrian-British economist and philosopher Friedrich Hayek. Since its publication in 1944, ''The Road to Serfdom'' has been popular among ...

,'' published in the U.S. by the University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It is operated by the University of Chicago and publishes a wide variety of academic titles, including ''The Chicago Manual of Style'', ...

in September 1944 with the help of Aaron Director

Aaron Director (; September 21, 1901 – September 11, 2004) was a Russian-born American economist and academic who played a central role in the development of the field Law and Economics and the Chicago school of economics. Director was a profe ...

, played a seminal role in transforming how Milton Friedman and others understood how society works. The University Press continued to publish a large number of Hayek's works in later years, such as ''The Fatal Conceit

''The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism'' is a book written by the economist and political philosopher Friedrich Hayek and edited by the philosopher William Warren Bartley. The book was first published in 1988 by the University of Chicago Pr ...

'' and '' The Constitution of Liberty''. In 1947, Hayek, Frank Knight

Frank Hyneman Knight (November 7, 1885 – April 15, 1972) was an American economist who spent most of his career at the University of Chicago, where he became one of the founders of the Chicago School. Nobel laureates Milton Friedman, George ...

, Friedman and George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

worked together in forming the Mont Pèlerin Society, an international forum for libertarian economists.

During 1950–1962, Hayek was a faculty member of the Committee of Social Thought at the University of Chicago, where he conducted a number of influential faculty seminars. There were a number of Chicago academics who worked on research projects sympathetic to some of Hayek's own, such as Aaron Director, who was active in the Chicago School in helping to fund and establish what became the "Law and Society" program in the University of Chicago Law School. Hayek and Friedman also cooperated in support of the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists, later renamed the Intercollegiate Studies Institute

The Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ISI) is a nonprofit educational organization that promotes conservative thought on college campuses.

It was founded in 1953 by Frank Chodorov with William F. Buckley Jr. as its first president. It sponsor ...

, an American student organisation devoted to libertarian ideas.

James M. Buchanan

James M. Buchanan (1919–2013) won the 1986Nobel Prize in Economics

The Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, officially the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel ( sv, Sveriges riksbanks pris i ekonomisk vetenskap till Alfred Nobels minne), is an economics award administered ...

for his public choice theory. He studied under Frank H. Knight at the University of Chicago, receiving PhD in 1948. Although he did not hold any position at the university afterwards, his later work is closely related to the thought of the Chicago school. Buchanan was the foremost proponent of the Virginia school of political economy.

Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell (born in 1930) received his PhD at the University of Chicago in 1968, underGeorge Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

. A libertarian conservative

Libertarian conservatism, also referred to as conservative libertarianism and conservatarianism, is a Political philosophy, political and social philosophy that combines Conservatism in the United States, conservatism and Libertarianism in the ...

in his perspective, he is considered to be a representative of the Chicago school.

Criticisms

Paul Douglas

Paul Howard Douglas (March 26, 1892 – September 24, 1976) was an American politician and Georgist economist. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Senator from Illinois for eighteen years, from 1949 to 1967. During his Senat ...

, economist and Democratic senator from Illinois for 18 years, was uncomfortable with the environment he found at the university. He stated that, "…I was disconcerted to find that the economic and political conservatives had acquired almost complete dominance over my department and taught that market decisions were always right and profit values the supreme ones… The opinions of my colleagues would have confined government to the eighteenth-century functions of justice, police, and arms, which I thought had been insufficient even for that time and were certainly so for ours. These men would neither use statistical data to develop economic theory nor accept critical analysis of the economic system… (Frank) Knight was now openly hostile, and his disciples seemed to be everywhere. If I stayed, it would be in an unfriendly environment."

While the efficacy of Eugene Fama

Eugene Francis "Gene" Fama (; born February 14, 1939) is an American economist, best known for his empirical work on portfolio theory, asset pricing, and the efficient-market hypothesis.

He is currently Robert R. McCormick Distinguished Servic ...

's efficient-market hypothesis

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) is a hypothesis in financial economics that states that asset prices reflect all available information. A direct implication is that it is impossible to "beat the market" consistently on a risk-adjusted bas ...

(EMH) was debated after the financial crisis of 2007–08

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of f ...

, proponents emphasized that the EMH is consistent with the large decline in asset prices since the event was unpredictable. Specifically, if market crashes never occurred, ''this'' would contradict the EMH since the average return of risky assets would be too large to justify the decreased risk of a large decline in prices; and if anything, the equity premium puzzle

The equity premium puzzle refers to the inability of an important class of economic models to explain the average equity risk premium (ERP) provided by a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities over that of U.S. Treasury Bills, which has been obser ...

implies that market crashes do not happen ''enough'' to justify the high Sharpe ratio

In finance, the Sharpe ratio (also known as the Sharpe index, the Sharpe measure, and the reward-to-variability ratio) measures the performance of an investment such as a security or portfolio compared to a risk-free asset, after adjusting for its ...

of US stocks and other risky assets.

Economist Brad DeLong

James Bradford "Brad" DeLong (born June 24, 1960) is an economic historian who is a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley. DeLong served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury in the Clin ...

of the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

says the Chicago School has experienced an "intellectual collapse", while Nobel laureate Paul Krugman

Paul Robin Krugman ( ; born February 28, 1953) is an American economist, who is Distinguished Professor of Economics at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and a columnist for ''The New York Times''. In 2008, Krugman was ...

of Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the ...

says that some recent comments from Chicago school economists are "the product of a Dark Age of macroeconomics in which hard-won knowledge has been forgotten", claiming that most peer-reviewed macroeconomic research since the mid-1960s has been wrong, preferring models developed in the 1930s. Chicago finance economist John Cochrane countered that these criticisms were ad hominem, displayed a "deep and highly politicized ignorance of what economics and finance is really all about", and failed to disentangle bubbles from rational risk premiums and crying wolf too many times in a row, emphasizing that even if these criticisms were true, it would make a stronger argument ''against'' regulation and control.

Finally, the school also has been criticized for training economists who advised the Chilean military junta during the 1970s and 1980s. However, they were credited with transforming Chile into Latin America's best performing economy (see Miracle of Chile

The "Miracle of Chile" was a term used by economist Milton Friedman to describe the reorientation of the Chilean economy in the 1980s and the effects of the economic policies applied by a large group of Chilean economists who collectively came ...

) with GDP per capita increasing from US$693 at the start of 1975 (the year Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and the ...

met with dictator Augusto Pinochet

Augusto José Ramón Pinochet Ugarte (, , , ; 25 November 1915 – 10 December 2006) was a Chilean general who ruled Chile from 1973 to 1990, first as the leader of the Military Junta of Chile from 1973 to 1981, being declared President of ...

; ninth highest of 12 South American countries) to $14,528 by the end of 2014 (the second highest in South America).

In the years since the reforms were introduced, the economic system implemented by the " Chicago Boys" (a label given to this group of economists) has mostly remained in place. The percent of total income earned by the richest 20% of the Chilean population in 2006 was 56.8%, while the percent of total income earned by the poorest 20% of the Chilean population was 4.1%, leaving a strong middle class earning 39.1% of total income.World Bank. (April 2010). Washington, DC: World Bank. Statistics retrieved October 1, 2010, froWorld Development Indicators database

Chile's Gini index (measure of income distribution) was 52.0 in 2006, compared to 24.7 of Denmark (most equally distributed) and 74.3 of Namibia (most unequally distributed). Chile has the widest inequality gap of any nation in the

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate e ...

.

A film titled ''Chicago Boys'', which had a highly critical view of the economic reforms, was released in Chile in November 2015.

See also

* Austrian school of economics *Chicago plan

The Chicago plan was a monetary and banking reform program suggested in the wake of the Great Depression by a group of University of Chicago economists including Henry Simons, Garfield Cox, Aaron Director, Paul Douglas, Albert G. Hart, Fra ...

* Mainstream economics

* Market monetarism

* Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought

References

Further reading

* Colander, David and Craig Freedman. 2019. ''Where Economics Went Wrong: Chicago’s Abandonment of Classical Liberalism''. Princeton: Princeton University Press. * Emmett, Ross B., ed. ''The Elgar Companion to the Chicago School of Economics'' (Edward Elgar, 2010), 350 pp.; * Emmett, Ross B. (2008). "Chicago School (new perspectives)", ''The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics

''The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics'' (2018), 3rd ed., is a twenty-volume reference work on economics published by Palgrave Macmillan. It contains around 3,000 entries, including many classic essays from the original Inglis Palgrave Diction ...

'', 2nd EditionAbstract

* Emmett, Ross B. (2009). Frank Knight and the Chicago school in American economics. Routledge * * * * * Johnson, Marianne. 2020. "''Where Economics Went Wrong'': A Review Essay." Journal of Economic Literature, 58 (3): 749–776. * * McCloskey, Deirdre N. (2010). Bourgeois dignity: Why economics can't explain the modern world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. . * * * * Reprinted in John Cunningham Wood & R.N. Woods (1990), ''Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments'', pp

343–393

* Shils, Edward, ed. (1991). Remembering the University of Chicago: teachers, scientists, and scholars. University of Chicago Press. * *

Description

preview

* *

External links

Thomas Sowell

The University of Chicago Department of Economics

* ttps://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.ECONOMICSDEPT Guide to the University of Chicago Department of Economics Records 1912–1961at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Chicago School Of Economics Conservatism in the United States Libertarianism in the United States Schools of economic thought

School of economics

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, particularly in modern ...

*