Cherokee History on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cherokee history is the

Cherokee history is the

The Cherokee are members of the

The Cherokee are members of the

"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs."

''Chronicles of Oklahoma.'' Vol. 16, No. 1, March 1938. (retrieved 21 Sept 2009) Other indigenous peoples also occupied territory and villages in Eastern Tennessee. For instance, the Long Hunter colonial expeditions of the 1760s recorded encountering Yuchi and

Much of what is known about pre-19th century

Much of what is known about pre-19th century

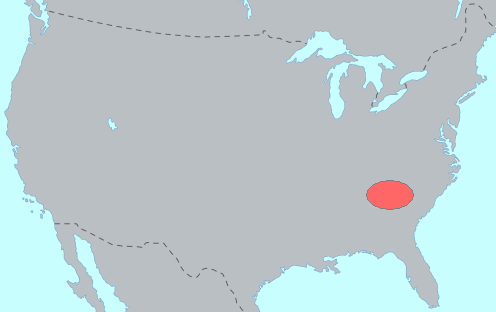

Regular encounter with English colonists began to take place in the mid-17th century. In 1650 the Cherokee were estimated to have a population of 22,500 persons, living primarily in independent towns and smaller villages along the river valleys of the South Appalachian Mountains in parts of present-day eastern Tennessee, the western parts of what are now defined as the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia. Their territory had an area of approximately 40,000 square miles (100,000 square km).

The first Anglo-Cherokee contact may have been in 1656, when English settlers in

Regular encounter with English colonists began to take place in the mid-17th century. In 1650 the Cherokee were estimated to have a population of 22,500 persons, living primarily in independent towns and smaller villages along the river valleys of the South Appalachian Mountains in parts of present-day eastern Tennessee, the western parts of what are now defined as the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia. Their territory had an area of approximately 40,000 square miles (100,000 square km).

The first Anglo-Cherokee contact may have been in 1656, when English settlers in

Cherokee history is the

Cherokee history is the written

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically inscribed, mechanically transferred, or digitally represented symbols.

Writing systems do not themselves constitute h ...

and oral

The word oral may refer to:

Relating to the mouth

* Relating to the mouth, the first portion of the alimentary canal that primarily receives food and liquid

**Oral administration of medicines

** Oral examination (also known as an oral exam or oral ...

lore, traditions, and historical record maintained by the living Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

people and their ancestors. In the 21st century, leaders of the Cherokee people define themselves as those persons enrolled in one of the three federally recognized

This is a list of federally recognized tribes in the contiguous United States of America. There are also federally recognized Alaska Native tribes. , 574 Indian tribes were legally recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) of the United ...

Cherokee tribes: The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

, The Cherokee Nation

The Cherokee Nation (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᎯ ᎠᏰᎵ ''Tsalagihi Ayeli'' or ᏣᎳᎩᏰᎵ ''Tsalagiyehli''), also known as the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, is the largest of three Cherokee federally recognized tribes in the United States. It ...

, and The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma ( or , abbreviated United Keetoowah Band or UKB) is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Native Americans headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. According to the UKB website, its member ...

.

The first live predominantly in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, the traditional heartland of the people; the latter two tribes are based in what is now Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, and was Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

when their ancestors were forcibly relocated there from the Southeast. The Cherokee people have extensive written records, including detailed genealogical records, preserved in the Cherokee language

200px, Number of speakers

Cherokee or Tsalagi ( chr, ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ, ) is an endangered-to-moribund Iroquoian language and the native language of the Cherokee people. ''Ethnologue'' states that there were 1,520 Cherokee speaker ...

, known as the Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s to write the Cherokee language. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy as he was illiterate until the creation of his syllabary. He f ...

, and in the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the is ...

.

Origins

The Cherokee are members of the

The Cherokee are members of the Iroquoian language

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian ...

-family of North American indigenous peoples, and are believed to have migrated in ancient times from the Great Lakes area, where most of such language families were located. The migration is recounted in their oral history. They established a homeland in the Southeastern Woodlands

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the nor ...

, an area that includes present-day western Virginia, southeastern Tennessee, western North and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia. In the late eighteenth century, the Cherokee moved further south and west, deeper into Georgia and Alabama.

The Mississippian culture was a civilization that influenced peoples throughout the Ohio and Mississippi valleys and into the Southeast. It was marked by dense town sites and extensive construction of platform mounds and other earthworks, used for religious and political purposes, and sometimes elite residences or burials.

In the Cherokee homeland of what is now western North Carolina, prehistoric platform mounds have been identified archeologically as built during the periods of the Woodland and South Appalachian Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, earth ...

s, by peoples who were ancestral to the historic Cherokee. The Mississippian culture was influential here beginning about 1000 CE, later than further north. Also, rather than large settlements featuring multiple mounds, in this homeland, most settlements with mounds featured one. They were often surrounded by smaller villages.

According to Benjamin A. Steere and the Western North Carolina Mounds and Towns Project, in association with the Eastern Band of Cherokee

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the United States. They are descended from the small ...

and University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

, as the historic Cherokee developed in this area, they began to create a different kind of public architecture, one that emphasized large townhouses standing on top of the mounds. During the next centuries, the Cherokee would add to or replace the townhouses and also maintain and enlarge the mounds in the process.

Cherokee culture shows association with Pisgah phase archeological sites, which were part of the Southern Appalachian Mississippian culture in this region. Artifacts from historic Cherokee towns also featured iconography from the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (formerly the Southern Cult), aka S.E.C.C., is the name given to the regional stylistic similarity of artifacts, iconography, ceremonies, and mythology of the Mississippian culture. It coincided with their ado ...

. This is believed likely to have been due to Cherokee assimilation of regional survivors during the expansion of this people.

Corn is traditionally central to the religious ceremonies of the Cherokee, especially the Green Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn Ceremony (Busk) is an annual ceremony practiced among various Native American peoples associated with the beginning of the yearly corn harvest. Busk is a term given to the ceremony by white traders, the word being a corruption of t ...

. This tradition was shared with other Iroquois-language tribes, as well as with the Creek, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, Yuchi, and Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

of the Southeast.

European contact

In 1540, at the time of theHernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

expedition, the Southeastern Woodlands region was inhabited by peoples of several mound-building cultures.

By the 1720s, the powerful Cherokee were well established at the southern end of the Great Appalachian Valley

The Great Appalachian Valley, also called The Great Valley or Great Valley Region, is one of the major landform features of eastern North America. It is a gigantic trough—a chain of valley lowlands—and the central feature of the Appalachian M ...

, having displaced the Muscogee Creek and other tribes.Brown, John P"Eastern Cherokee Chiefs."

''Chronicles of Oklahoma.'' Vol. 16, No. 1, March 1938. (retrieved 21 Sept 2009) Other indigenous peoples also occupied territory and villages in Eastern Tennessee. For instance, the Long Hunter colonial expeditions of the 1760s recorded encountering Yuchi and

Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the entire ...

-speaking traders and villages.

The Cherokee are believed to have settled more deeply into Georgia and Alabama in the late eighteenth century.

A Cherokee myth recorded in the late 18th century says that a "Moon-eyed people

The moon-eyed people are a legendary group of short, bearded white-skinned people who are said to have lived in Appalachia until the Cherokee expelled them. Stories about them, attributed to Cherokee tradition, are mentioned by early European se ...

" had lived in the Cherokee regions before they arrived. The group was described in 1797 by Colonel Leonard Marbury to Benjamin Smith Barton

Benjamin Smith Barton (February 10, 1766 – December 19, 1815) was an American botanist, naturalist, and physician. He was one of the first professors of natural history in the United States and built the largest collection of botanical specimen ...

. According to Marbury, when the Cherokee arrived in the area, they had encountered a "moon-eyed" people who could not see in the day-time.

Early culture

Cherokee culture

Cherokee society ( in the Cherokee language) is the culture and societal structures shared by the Cherokee Peoples. It can also mean the extended family or village. The Cherokee are Indigenous to the mountain and inland regions of the southeaster ...

and society comes from the papers of American writer John Howard Payne

John Howard Payne (June 9, 1791 – April 10, 1852) was an American actor, poet, playwright, and author who had nearly two decades of a theatrical career and success in London. He is today most remembered as the creator of "Home! Sweet Home ...

. The Payne papers describe the oral account by Cherokee elders of a traditional societal structure in which a "white" organization of elders represented the seven clans. According to Payne, this group, which was hereditary and described as priestly, was responsible for religious activities such as healing, purification, and prayer. A second group of younger men, the "red" organization, was responsible for warfare. Because warfare was considered a polluting activity, the priestly class conducted purification ceremonies of participants before they could reintegrate into normal village life. This hierarchy had disappeared long before the 18th century. The reasons for the change have been debated, with the origin of the decline traced to a revolt by the Cherokee against the abuses of the priestly class known as the Ani-kutani The Ani-kutani (ᎠᏂᎫᏔᏂ) were the ancient priesthood of the Cherokee people. According to Cherokee legend, the Ani-Kutani were slain during a mass uprising by the Cherokee people approximately 300 years prior to European contact. This upr ...

. ("Aní-" is a prefix referring to a group of individuals, while the meaning of "kutáni" is unknown).Irwin 1992.

Early American ethnographer James Mooney

James Mooney (February 10, 1861 – December 22, 1921) was an American ethnographer who lived for several years among the Cherokee. Known as "The Indian Man", he conducted major studies of Southeastern Indians, as well as of tribes on the Gr ...

, who lived with and studied the Cherokee in the late 1880s, was the first to write about the decline of the former hierarchy in relation to this revolt.Mooney (1900/1995), ''Myths of the Cherokee'', p. 392. By the time Mooney lived with the Cherokee, their development of religious practitioners was more informal. It was based more on individual knowledge and ability than upon heredity.

Another major source of early cultural history comes from materials written in the 19th century by the ''didanvwisgi'' (Cherokee:ᏗᏓᏅᏫᏍᎩ), Cherokee medicine men

A medicine man is a traditional healer and spiritual leader among the indigenous people of the Americas.

Medicine Man or The Medicine Man may also refer to:

Films

* ''The Medicine Man'' (1917 film), an American silent film directed by Clifford S ...

, using the Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s to write the Cherokee language. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy as he was illiterate until the creation of his syllabary. He f ...

created by Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

in the 1820s. Initially only the ''didanvwisgi'' used these materials, which were considered extremely powerful. Later, the writings were widely adopted by the Cherokee people.

Unlike most other Indians in the American southeast at the start of the historic era, the Cherokee spoke an Iroquoian language

The Iroquoian languages are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, all surviving Iroquoian ...

. Since the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

region was the core of Iroquoian-language speakers, scholars have theorized that the Cherokee migrated south from that region. However, some argue that the Iroquois all migrated north from the southeast, with the Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

breaking off from that group during the migration and settling in South Carolina. Linguistic analysis shows a relatively large difference between Cherokee and the northern Iroquoian languages, suggesting a split between the peoples in the distant past. Glottochronology Glottochronology (from Attic Greek γλῶττα ''tongue, language'' and χρόνος ''time'') is the part of lexicostatistics which involves comparative linguistics and deals with the chronological relationship between languages.Sheila Embleton ( ...

studies suggest the split occurred between about 1,500 and 1,800 B.C.

The Cherokee identify their ancient settlement of Kituwa

Kituwa (also spelled Kituwah, Keetoowah, Kittowa, Kitara and other similar variations) or ''giduwa'' (Cherokee: ᎩᏚᏩ) is an ancient Native American settlement near the upper Tuckasegee River, and is claimed by the Cherokee people as their ori ...

on the Tuckasegee River

The Tuckasegee River (variant spellings include Tuckaseegee and Tuckaseigee) flows entirely within western North Carolina. It begins its course in Jackson County above Cullowhee at the confluence of Panthertown and Greenland creeks.

It flows ...

, formerly next to and now part of Qualla Boundary

The Qualla Boundary or The Qualla is territory held as a land trust by the United States government for the federally recognized Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, who reside in western North Carolina. The area is part of the large historic Chero ...

(the reservation of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

), as the original Cherokee settlement in the Southeast.

16th century: Spanish contact

The first known Cherokee contact with Europeans was in late May 1540, when a Spanish expedition led byHernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and '' conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

passed through Cherokee country near present-day Embreeville, Tennessee

Embreeville is an unincorporated community and census-designated place in southern Washington County, Tennessee. It is located along the Nolichucky River and on State Routes 81 and 107.

The population of the CDP was 429 at the 2020 census.

Demog ...

, which the Spaniards referred to as ''Guasili''. De Soto's expedition visited many of the villages later identified as Cherokee in Georgia and Tennessee. It recorded a ''Chalaque'' nation as living around the Keowee River

The Keowee River is created by the confluence of the Toxaway River and the Whitewater River in northern Oconee County, South Carolina. The confluence is today submerged beneath the waters of Lake Jocassee, a reservoir created by Lake Jocassee D ...

where present-day North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia meet. New infectious diseases carried by the Spaniards and their animals decimated the Cherokee and other Eastern tribes, who had no immunity.

A second Spanish expedition came through Cherokee country in 1567 led by Juan Pardo. He was seeking an overland route to Mexican silver mines; the Spanish mistakenly thought the Appalachians were connected to a range in Mexico. Spanish troops built six forts in the interior southeast, including at Joara

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles from the Atlantic coast in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joara is n ...

, a Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

. They also visited the Cherokee towns Nikwasi

Nikwasi ( chr, ᏁᏆᏏ, translit=Nequasi or Nequasee) comes from the Cherokee word for "star", ''Noquisi'' (No-kwee-shee), and is the site of the Cherokee town which is first found in colonial records in the early 18th century, but is much older ...

, Estatoe, Tugaloo

Tugaloo (''Dugiluyi'' (ᏚᎩᎷᏱ)) was a Cherokee town located on the Tugaloo River, at the mouth of Toccoa Creek. It was south of Toccoa and Travelers Rest State Historic Site in present-day Stephens County, Georgia. Cultures of ancient ind ...

, Conasauga, and Kituwa

Kituwa (also spelled Kituwah, Keetoowah, Kittowa, Kitara and other similar variations) or ''giduwa'' (Cherokee: ᎩᏚᏩ) is an ancient Native American settlement near the upper Tuckasegee River, and is claimed by the Cherokee people as their ori ...

, but ultimately failed to gain dominion over the region and retreated to the coast. The Native Americans rebelled against their efforts, killing all but one of the garrison soldiers among the six forts. Pardo had already returned to his base. The Spanish did not try to settle this area again.

17th century: English contact

Regular encounter with English colonists began to take place in the mid-17th century. In 1650 the Cherokee were estimated to have a population of 22,500 persons, living primarily in independent towns and smaller villages along the river valleys of the South Appalachian Mountains in parts of present-day eastern Tennessee, the western parts of what are now defined as the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia. Their territory had an area of approximately 40,000 square miles (100,000 square km).

The first Anglo-Cherokee contact may have been in 1656, when English settlers in

Regular encounter with English colonists began to take place in the mid-17th century. In 1650 the Cherokee were estimated to have a population of 22,500 persons, living primarily in independent towns and smaller villages along the river valleys of the South Appalachian Mountains in parts of present-day eastern Tennessee, the western parts of what are now defined as the states of North Carolina and South Carolina, and northeastern Georgia. Their territory had an area of approximately 40,000 square miles (100,000 square km).

The first Anglo-Cherokee contact may have been in 1656, when English settlers in Virginia Colony

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

recorded that six to seven hundred "Mahocks, Nahyssan

The Tutelo (also Totero, Totteroy, Tutera; Yesan in Tutelo) were Native American people living above the Fall Line in present-day Virginia and West Virginia. They spoke a Siouan dialect of the Tutelo language thought to be similar to that of thei ...

s and Rechahecrians" had encamped at Bloody Run, located on the eastern edge of present-day Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. A combined force of English and tributary Pamunkey

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe is one of 11 Virginia Indian tribal governments recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the state's first federally recognized tribe, receiving its status in January 2016. Six other Virginia tribal governments, t ...

drove them off, but the Pamunkey chief Totopotomoi

Totopotomoi (c. 1615–1656) was a Native American leader from what is now Virginia. He served as the chief of Pamunkey and as ''werowance'' of the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom for the term lasting from about 1649-1656, when he died in the Battle ...

was slain in the battle. While the first two named groups are considered to be Virginia Siouan, the identity of the ''Rechahecrians'' has been much debated. Historians have noted that the name closely resembles that of the ''Eriechronon'', commonly known as the Erie tribe

The Erie people (also Eriechronon, Riquéronon, Erielhonan, Eriez, Nation du Chat) were Indigenous people historically living on the south shore of Lake Erie. An Iroquoian group, they lived in what is now western New York, northwestern Pennsylvani ...

, an Iroquoian people who had been driven away from the southern shore of Lake Erie

Lake Erie ( "eerie") is the fourth largest lake by surface area of the five Great Lakes in North America and the eleventh-largest globally. It is the southernmost, shallowest, and smallest by volume of the Great Lakes and therefore also has t ...

in 1654 during the Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

by the powerful Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

Five Nations based to the east. Anthropologist

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and ...

Martin Smith theorized that remnants of the Erie migrated to Virginia after the wars. ( 1986:131–32) Robert J. Conley (Cherokee) and a few other historians have suggested that the Erie were identical to the Cherokee, but this view does not have a consensus. Although believed to have been Iroquoian, the Erie language

Erie was believed to have been an Iroquoian language spoken by the Erie people, similar to Wyandot. But it was poorly documented, and linguists are not certain that this conclusion is correct. There have been no known connections between the Erie ...

was too scarcely documented for linguists to fully place its relationship to Cherokee or other Iroquoian languages.

In 1673, fur trader Abraham Wood

Abraham Wood (1610–1682), sometimes referred to as "General" or "Colonel" Wood, was an English fur trader, militia officer, politician and explorer of 17th century colonial Virginia. Wood helped build and maintained Fort Henry at the falls of ...

from Fort Henry (modern Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines Petersburg (along with the city of Colonial Heights) with Din ...

) sent two English traders, James Needham and Gabriel Arthur, to the Overhill Cherokee

Overhill Cherokee was the term for the Cherokee people located in their historic settlements in what is now the U.S. state of Tennessee in the Southeastern United States, on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. This name was used by 1 ...

country on the west side of the Appalachians. Wood hoped to forge a direct trading connection with the Cherokee to bypass the Occaneechi

The Occaneechi (also Occoneechee and Akenatzy) are Native Americans who lived in the 17th century primarily on the large, long Occoneechee Island and east of the confluence of the Dan and Roanoke rivers, near current-day Clarksville, Virginia. ...

people in Virginia, who acted as middlemen on the Trading Path

The Trading Path (a.k.a. Occaneechi Path, The Path to the Catawba, the Catawba Road, Indian Trading Path, Unicoi Turnpike, Warriors' Path, etc.) is not simply one wide path, as many named historic roads were or are. It was a corridor of roads an ...

. The two Virginia colonists likely made contact with the Cherokee. Wood called the people ''Rickohockens'' in his book of the expedition. The map accompanying the book, showed the Rickohockens occupying all of present-day southwestern Virginia, southeastern Kentucky, northwestern North Carolina and the northeastern tip of Tennessee. These areas on both sides of the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

have been considered the homelands of the Cherokee, together with western South Carolina and northeastern Georgia.

Needham departed with a guide nicknamed 'Indian John,' while Arthur stayed in Chota to learn the Cherokee language. On his journey, Needham argued with 'Indian John', who killed him. 'Indian John' tried to encourage his people to kill Arthur, too, but the chief prevented this. Disguised as a Cherokee, Arthur accompanied the Chota chief on raids of Spanish settlements in Florida, Indian communities on the southeast coast, and Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

towns on the Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

. In 1674 he was captured by the Shawnee, who discovered that he was a white man. The Shawnee allowed him to return to Chota. In June 1674, the Chota chief escorted Arthur back to his English settlement in Virginia.

By the late 17th century, colonial traders from both Virginia and South Carolina were making regular journeys to Cherokee lands, but few wrote about their experiences. Historians have studied records of colonial laws and lawsuits involving traders to learn more about these early years. The English and other Europeans were seeking mainly deerskins, raw material for the booming European leather industry, in exchange for which they traded European "trade goods" that featured technology new to the Native Americans, such as iron and steel tools (kettles, knives, etc.), firearms, gunpowder, and ammunition. In 1705, traders complained that they were losing business to the Indian slave trade

Slavery among Native Americans in the United States includes slavery by and slavery of Native Americans roughly within what is currently the United States of America.

Tribal territories and the slave trade ranged over present-day borders. ...

, instigated and supported by Governor James Moore of the Province of South Carolina. Moore had commissioned people to "set upon, assault, kill, destroy, and take captive as many Indians as possible".Mooney, p. 32. When the captives were sold, slave traders split profits with the Governor. Although colonial governments from an early period prohibited selling alcohol to Indians, traders commonly used rum, and later whiskey, as common items of trade.

During the early historic era, Europeans classified the Cherokee towns by such terms as Lower, Middle, and Overhill to designate them geographically, in relation to the colonists' bases on the Atlantic coast. The Lower Towns were situated along the headwater streams of the Keowee River

The Keowee River is created by the confluence of the Toxaway River and the Whitewater River in northern Oconee County, South Carolina. The confluence is today submerged beneath the waters of Lake Jocassee, a reservoir created by Lake Jocassee D ...

(known as the Savannah River

The Savannah River is a major river in the southeastern United States, forming most of the border between the states of South Carolina and Georgia. Two tributaries of the Savannah, the Tugaloo River and the Chattooga River, form the norther ...

in its lower reaches), mainly in present-day western South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and northeastern Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. ''Keowee

Keowee ( chr, ᎫᏩᎯᏱ, translit=Guwahiyi) was a Cherokee town in the far northwest corner of present-day South Carolina. It was the principal town of what were called the seven Lower Towns, located along the Keowee River (Colonists referred ...

'' was one of the chief Lower towns, as was ''Tugaloo

Tugaloo (''Dugiluyi'' (ᏚᎩᎷᏱ)) was a Cherokee town located on the Tugaloo River, at the mouth of Toccoa Creek. It was south of Toccoa and Travelers Rest State Historic Site in present-day Stephens County, Georgia. Cultures of ancient ind ...

''.

The Middle Towns were located in present Western North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, on the headwater streams of the Tennessee River, such as the upper Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portio ...

, upper Hiwassee River, and upper French Broad River. Among several chief towns were ''Nikwasi

Nikwasi ( chr, ᏁᏆᏏ, translit=Nequasi or Nequasee) comes from the Cherokee word for "star", ''Noquisi'' (No-kwee-shee), and is the site of the Cherokee town which is first found in colonial records in the early 18th century, but is much older ...

''. The Out Towns, including the ancient 'mother town' of Kituwa

Kituwa (also spelled Kituwah, Keetoowah, Kittowa, Kitara and other similar variations) or ''giduwa'' (Cherokee: ᎩᏚᏩ) is an ancient Native American settlement near the upper Tuckasegee River, and is claimed by the Cherokee people as their ori ...

, were along the upper Tuckaseegee River

The Tuckasegee River (variant spellings include Tuckaseegee and Tuckaseigee) flows entirely within western North Carolina. It begins its course in Jackson County above Cullowhee at the confluence of Panthertown and Greenland creeks.

It flows ...

and Oconaluftee River

The Oconaluftee River drains the south-central Oconaluftee valley of the Great Smoky Mountains in Western North Carolina before emptying into the Tuckasegee River. The river flows through the Qualla Boundary, a federal land trust that serves as ...

. The Valley Towns were along the Nantahala River

The Nantahala River ()

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

In the 1660s, the Cherokee had given sanctuary to a band of Shawnee. But 50 years later, from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw, allied with the English, fought the Shawnee, who were allied with the French, and forced them to move north. The Cherokee were also allied with the English and the

In the 1660s, the Cherokee had given sanctuary to a band of Shawnee. But 50 years later, from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw, allied with the English, fought the Shawnee, who were allied with the French, and forced them to move north. The Cherokee were also allied with the English and the

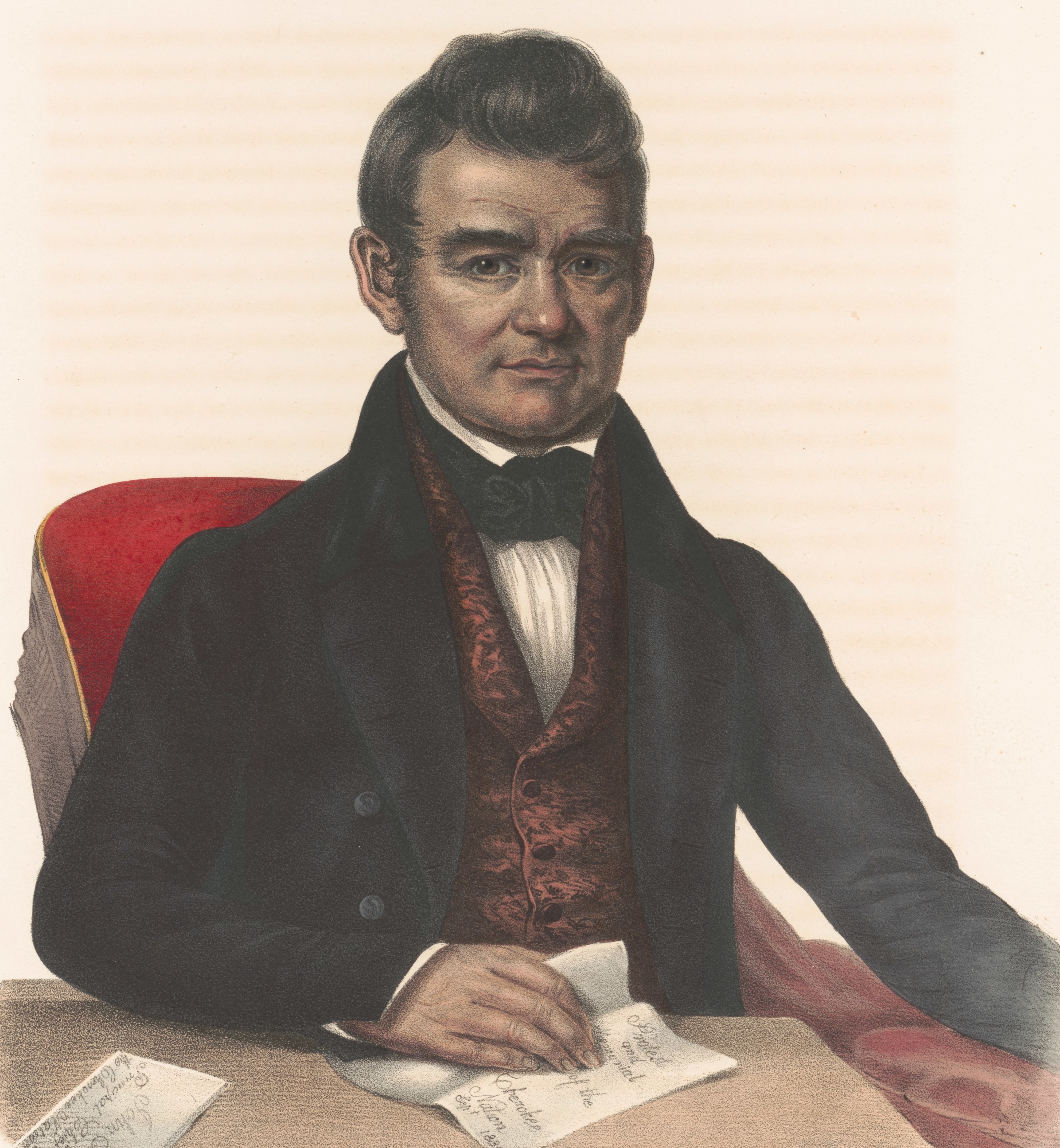

Early in the 19th century, the Cherokees were led by Principal Chiefs

Early in the 19th century, the Cherokees were led by Principal Chiefs

Cherokees were displaced from their ancestral lands in northern Georgia and the Carolinas in a period of rapidly expanding white population. Some of the rapid expansion was due to a

Cherokees were displaced from their ancestral lands in northern Georgia and the Carolinas in a period of rapidly expanding white population. Some of the rapid expansion was due to a

Some Cherokee in the western area of North Carolina were able to evade removal, and they became the East Band of Cherokee Indians.

Some Cherokee in the western area of North Carolina were able to evade removal, and they became the East Band of Cherokee Indians.

''History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians).'' (2007-03-10) or negotiated directly with the state government to stay locally. Many were from the former Valley Towns area around the

''History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians).'' (2007-03-10) The Cherokee in Indian Territory split into Confederate (the majority) and Union factions. They were influenced both by many leaders being slaveholders and by Confederate promises to establish an Indian state if they won the war. There was warfare within the tribe, and many Union supporters escaped to Kansas to survive.

The United States required the Cherokee and other tribes that had allied with the Confederacy to make new treaties. Among the new terms was a requirement to emancipate their slaves, and to provide citizenship to those freedmen who wanted to remain with the Cherokee Nation. If they went to US territory, the African Americans would become US citizens. By an 1866 treaty with the US government, the Cherokee agreed to grant tribal citizenship to

The United States required the Cherokee and other tribes that had allied with the Confederacy to make new treaties. Among the new terms was a requirement to emancipate their slaves, and to provide citizenship to those freedmen who wanted to remain with the Cherokee Nation. If they went to US territory, the African Americans would become US citizens. By an 1866 treaty with the US government, the Cherokee agreed to grant tribal citizenship to  The

The

"Sequoyah"

''New Georgia Encyclopedia'', accessed 3 January 2009.

*

A Cherokee Encyclopedia.

' Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007. . * Halliburton, R., jr.: ''Red over Black – Black Slavery among the Cherokee Indians'', Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, U.S.A, 1977, * Hill, Sarah H

''Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry''

Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997. . * Irwin, L, "Cherokee Healing: Myth, Dreams, and Medicine." ''American Indian Quarterly''. Vol. 16, 2, 1992, p. 237. * Mooney, James. "Myths of the Cherokees." Bureau of American Ethnology, Nineteenth Annual Report, 1900, Part I. pp. 1–576. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. * Perdue, Theda. "Clan and Court: Another Look at the Early Cherokee Republic." ''American Indian Quarterly''. Vol. 24, 4, 2000, p. 562. * Wishart, David M. "Evidence of Surplus Production in the Cherokee Nation Prior to Removal." ''Journal of Economic History''. Vol. 55, 1, 1995, p. 120. {{DEFAULTSORT:Cherokee History Indian Territory History of Oklahoma Pre-statehood history of Alabama Pre-statehood history of Tennessee Pre-statehood history of Oklahoma History of the Southern United States Native American history by tribe

, from the North Carolina Collection's website at the

Valley River

A valley is an elongated low area often running between hills or mountains, which will typically contain a river or stream running from one end to the other. Most valleys are formed by erosion of the land surface by rivers or streams ove ...

s.

The Overhill Towns were located across the higher mountains in present-day eastern Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and northwestern Georgia, along the Tennessee and Tellico River, one of its tributaries. Principal towns included ''Chota'', ''Tellico'', and ''Tanasi

Tanasi ( chr, ᏔᎾᏏ, translit=Tanasi) (also spelled Tanase, Tenasi, Tenassee, Tunissee, Tennessee, and other such variations) was a historic Overhill settlement site in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. ...

''. The Europeans, primarily English, used these terms to describe their changing geopolitical relationship with the Cherokee.

Two more groups of towns were often listed in these groupings, both in Western North Carolina: the Out Towns, based along the Tuckaseegee and Onconaluftee rivers. The chief town was ''Kituwa'' on the Tuckaseegee River, considered by the Cherokee as their 'mother town'. The Valley Towns were along the Nantahala and Valley rivers. Their chief town was ''Tomotley'' on the Valley River (this is not the same as Tomotley

Tomotley (also known as Tamahli) is a prehistoric and historic Native American site along the lower Little Tennessee River in Monroe County, Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. Occupied as early as the Archaic period (8000 to 1000 BCE), ...

on the lower Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portio ...

in what is now Tennessee). The former shared the dialect of the Middle Towns and the latter that of the Overhill people (later known as Upper) Towns.

Of the southeastern Indian confederacies of the late 17th and early 18th centuries (Creek

A creek in North America and elsewhere, such as Australia, is a stream that is usually smaller than a river. In the British Isles it is a small tidal inlet.

Creek may also refer to:

People

* Creek people, also known as Muscogee, Native Americans

...

(Muscogee), Chickasaw

The Chickasaw ( ) are an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Their traditional territory was in the Southeastern United States of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee as well in southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as ...

, Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

, etc.), the Cherokee were one of the most populous and powerful. They were relatively isolated by their hilly and mountainous homeland. Virginia colonists started trading with them in the late 17th century. In the 1690s, the Cherokee founded a much stronger and more important trade relationship with the colony of South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, which was based in the port of Charles Town on the Atlantic coast. By the 18th century, South Carolina overshadowed Virginia trading with the Cherokee.

18th century history

In the 1660s, the Cherokee had given sanctuary to a band of Shawnee. But 50 years later, from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw, allied with the English, fought the Shawnee, who were allied with the French, and forced them to move north. The Cherokee were also allied with the English and the

In the 1660s, the Cherokee had given sanctuary to a band of Shawnee. But 50 years later, from 1710 to 1715, the Cherokee and Chickasaw, allied with the English, fought the Shawnee, who were allied with the French, and forced them to move north. The Cherokee were also allied with the English and the Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

, and Catawba Catawba may refer to:

*Catawba people, a Native American tribe in the Carolinas

*Catawba language, a language in the Catawban languages family

*Catawban languages

Botany

* Catalpa, a genus of trees, based on the name used by the Catawba and other ...

in late 1712 and early 1713, against the Tuscarora Tuscarora may refer to the following:

First nations and Native American people and culture

* Tuscarora people

**''Federal Power Commission v. Tuscarora Indian Nation'' (1960)

* Tuscarora language, an Iroquoian language of the Tuscarora people

* ...

in the Second Tuscarora War

The Tuscarora War was fought in North Carolina from September 10, 1711 until February 11, 1715 between the Tuscarora people and their allies on one side and European American settlers, the Yamassee, and other allies on the other. This was cons ...

. Following their defeat, most of the Tuscarora, another Iroquoian-language tribe, migrated north to New York. By 1722 they had been accepted as the 6th Nation in the League of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

.

In the Southeast, the English and Cherokee began an alliance that remained strong for much of the 18th century. In January 1716, Cherokee warriors murdered a delegation of Muscogee Creek leaders who were visiting at Tugaloo

Tugaloo (''Dugiluyi'' (ᏚᎩᎷᏱ)) was a Cherokee town located on the Tugaloo River, at the mouth of Toccoa Creek. It was south of Toccoa and Travelers Rest State Historic Site in present-day Stephens County, Georgia. Cultures of ancient ind ...

, marking the Cherokee's entry into the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

. This ended in 1717 with peace treaties between South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

and the Creek. Hostility and sporadic raids between the Cherokee and Creek continued for decades.Oatis, Steven J. ''A Colonial Complex: South Carolina's Frontiers in the Era of the Yamasee War, 1680–1730.'' Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004. . These raids came to a head at the Battle of Taliwa

The Battle of Taliwa was fought in Ball Ground, Georgia in 1755. The battle was part of a larger campaign of the Cherokee against the Muscogee Nation, Muscogee Creek people, where an army of 500 Cherokee warriors led by Oconostota (c. 1710–1783) ...

in 1755 (in present-day Ball Ground, Georgia

Ball Ground is a city in Cherokee County, Georgia, United States. The city was originally Cherokee territory before they were removed from the land and it was given to white settlers. A railroad was built in 1882 and a town was formed around th ...

), resulting in the defeat of the Muscogee.

In 1721, the Cherokee ceded lands to South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. In 1730, at Nikwasi

Nikwasi ( chr, ᏁᏆᏏ, translit=Nequasi or Nequasee) comes from the Cherokee word for "star", ''Noquisi'' (No-kwee-shee), and is the site of the Cherokee town which is first found in colonial records in the early 18th century, but is much older ...

, Sir Alexander Cumming persuaded the Cherokee to crown Moytoy of Tellico

Moytoy of Tellico, (died 1741) was a prominent leader of the Cherokee in the American Southeast.

Titles

Moytoy was given the title of "Emperor of the Cherokee" by Sir Alexander Cumming, a Scots-Anglo trade envoy in what was then the Province of ...

as "Emperor." Moytoy agreed to recognize King George II of Great Britain

, house = Hanover

, religion = Protestant

, father = George I of Great Britain

, mother = Sophia Dorothea of Celle

, birth_date = 30 October / 9 November 1683

, birth_place = Herrenhausen Palace,Cannon. or Leine ...

as the Cherokee protector. Seven prominent Cherokee, including Attakullakulla

Attakullakulla (Cherokee language, Cherokee”Tsalagi”, (ᎠᏔᎫᎧᎷ) ''Atagukalu''; also spelled Attacullaculla and often called Little Carpenter by the English) (c. 1715 – c. 1777) was an influential Cherokee leader and the tr ...

, traveled with Cuming back to London, England

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

. The Cherokee delegation signed the Treaty of Whitehall with the British. Moytoy's son, Amo-sgasite (Dreadful Water) attempted to succeed him as "Emperor" in 1741, but the Cherokee elected their own leader, Old Hop

Conocotocko of Chota ( chr, ᎬᎾᎦᏙᎦ, Gvnagadoga, "Standing Turkey"), known in English as Old Hop, was a Cherokee elder, serving as the First Beloved Man of the Cherokee from 1753 until his death in 1760. Settlers of European ancestry r ...

of Chota (sometimes spelled or recorded as Echota).

Political power among the Cherokee remained decentralized, with towns acting autonomously. In 1735 the Cherokee were estimated to have sixty-four towns and villages and 6000 fighting men. A significant interaction between European and American peoples was embodied in the assimilation of Gottlieb Priber into Cherokee society, a German radical who advocated for a trans-tribal region-wide Indian confederation to oppose European colonization of Native land. In 1738 and 1739 smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

epidemics broke out among the Cherokee, who had no natural immunity to the new infectious disease. It was endemic among English and European populations, who had been living (and dying) with the virus for centuries. Nearly half the Cherokee population died within a year. Many other —possibly hundreds —of Cherokee survivors committed suicide, due to the disfigurement of their skin from the disease.

From 1753 to 1755, battles broke out between the Cherokee and Muscogee over disputed hunting grounds in North Georgia

North Georgia is the northern hilly/mountainous region in the U.S. state of Georgia. At the time of the arrival of settlers from Europe, it was inhabited largely by the Cherokee. The counties of north Georgia were often scenes of important eve ...

. The Cherokee were victorious in the Battle of Taliwa. British soldiers built forts in Cherokee country to confront the French during the years of the French and Indian War, the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe. These included Fort Loudoun, along the Little Tennessee River

The Little Tennessee River is a tributary of the Tennessee River that flows through the Blue Ridge Mountains from Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, into North Carolina, and then into Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. It drains portio ...

near Chota, a major Cherokee town.

In 1756 the Cherokee fought alongside the British in the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

; however, serious misunderstandings between the two allies arose quickly, resulting in the 1760 Anglo-Cherokee War

The Anglo-Cherokee War (1758–1761; in the Cherokee language: the ''"war with those in the red coats"'' or ''"War with the English"''), was also known from the Anglo-European perspective as the Cherokee War, the Cherokee Uprising, or the Cherok ...

. In the peace treaty ending the Seven Years' War, Britain took over the North American territories of defeated France east of the Mississippi River. King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

forbidding British settlements west of the Appalachian crest, attempting to afford some protection from colonial encroachment to the Cherokee and other tribes, but the prohibition proved difficult to enforce.

In 1769–72, predominantly Virginian settlers squatting on Cherokee lands in Tennessee, formed the Watauga Association

The Watauga Association (sometimes referred to as the Republic of Watauga) was a semi-autonomous government created in 1772 by frontier settlers living along the Watauga River in what is now Elizabethton, Tennessee. Although it lasted only a few ...

. In "Kentuckee", Daniel Boone

Daniel Boone (September 26, 1820) was an American pioneer and frontiersman whose exploits made him one of the first folk heroes of the United States. He became famous for his exploration and settlement of Kentucky, which was then beyond the we ...

and his party tried to create a settlement in what would become the Transylvania colony

The Transylvania Colony, also referred to as the Transylvania Purchase, was a short-lived, extra-legal colony founded in early 1775 by North Carolina land speculator Richard Henderson, who formed and controlled the Transylvania Company. Henders ...

. Some Shawnee, Lenape

The Lenape (, , or Lenape , del, Lënapeyok) also called the Leni Lenape, Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada. Their historical territory includ ...

(Delaware), Mingo

The Mingo people are an Iroquoian group of Native Americans, primarily Seneca and Cayuga, who migrated west from New York to the Ohio Country in the mid-18th century, and their descendants. Some Susquehannock survivors also joined them, and ...

, and Cherokee attacked a scouting and foraging party that included Boone's son. This sparked the beginning of what was known as Dunmore's War

Lord Dunmore's War—or Dunmore's War—was a 1774 conflict between the Colony of Virginia and the Shawnee and Mingo American Indian nations.

The Governor of Virginia during the conflict was John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore—Lord Dunmore. He a ...

(1773–1774).

In 1776, allied with the Shawnee and led by Cornstalk

Cornstalk (c. 1720? – November 10, 1777) was a Shawnee leader in the Ohio Country in the 1760s and 1770s. His name in the Shawnee language was Hokoleskwa. Little is known about his early life. He may have been born in the Province of Pennsylv ...

, Cherokee attacked settlers in South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, the Washington District

The Washington District is a Norfolk Southern Railway line in the U.S. state of Virginia that connects Alexandria and Lynchburg. Most of the line was originally built from 1850 to 1860 by the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, with a small portion ...

and North Carolina in the Second Cherokee War. Nancy Ward

''Nanyehi'' (Cherokee: ᎾᏅᏰᎯ: "One who goes about"), known in English as Nancy Ward (c. 1738 – 1822 or 1824), was a Beloved Woman and political leader of the Cherokee. She advocated for peaceful coexistence with European Americans and, ...

(Overhill Cherokee and a niece of Dragging Canoe

Dragging Canoe (ᏥᏳ ᎦᏅᏏᏂ, pronounced ''Tsiyu Gansini'', "he is dragging his canoe") (c. 1738 – February 29, 1792) was a Cherokee war chief who led a band of Cherokee warriors who resisted colonists and United States settlers in the ...

), had warned pioneer settlers of the impending attacks. European-American militias retaliated, destroying over 50 Cherokee towns. In 1777, most of the surviving Cherokee town leaders signed treaties with the newly established states during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

Dragging Canoe and his band, however, moved to the area near present-day Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, establishing 11 new towns. Chickamauga was his headquarters and his band became known as the Chickamauga; some people mistakenly described them as a distinct tribe of Cherokee. From here he led fighting of a guerrilla-style war against settlers, which became known as the Cherokee–American wars

The Cherokee–American wars, also known as the Chickamauga Wars, were a series of raids, campaigns, ambushes, minor skirmishes, and several full-scale frontier battles in the Old Southwest from 1776 to 1794 between the Cherokee and American se ...

. The Treaty of Tellico Blockhouse, signed 7 November 1794 with , ended the Cherokee–American wars.

19th century

Early in the 19th century, the Cherokees were led by Principal Chiefs

Early in the 19th century, the Cherokees were led by Principal Chiefs Little Turkey

Little Turkey (1758–1801) was First Beloved Man of the Cherokee people, becoming, in 1794, the first Principal Chief of the original Cherokee Nation.

Headman

Little Turkey, born in 1758, was elected First Beloved Man by the general council of ...

(1788–1801), Black Fox (1801–1811), and Pathkiller

Pathkiller, (died January 8, 1827) was a Cherokee warrior and Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

Warrior life

PathkillerPathkiller is a Cherokee rank or title—not a name. His original name is unknown. fought against the Overmountain Men ...

(1811–1827). The seat of the Cherokee after 1788 was at Ustanali

New Town( chr, ᎤᏍᏔᎾᎵ, translit=Ustanali) is an unincorporated community in Gordon County, Georgia, United States, located northeast of Calhoun. New Town is near the New Echota historic site, which was formerly part of the Cherokee Natio ...

(near Calhoun, Georgia

Calhoun is a city in Gordon County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 16,949. Calhoun is the county seat of Gordon County.

History

In December 1827, Georgia had already claimed the Cherokee lands that be ...

); in 1825 nearby New Echota

New Echota was the capital of the Cherokee Nation (1794–1907), Cherokee Nation in the Southeast United States from 1825 until their Cherokee removal, forced removal in the late 1830s. New Echota is located in present-day Gordon County, Georgi ...

became the Cherokee capital. Former warriors James Vann and his protégés Major Ridge

Major Ridge, The Ridge (and sometimes Pathkiller II) (c. 1771 – 22 June 1839) (also known as ''Nunnehidihi'', and later ''Ganundalegi'') was a Cherokee leader, a member of the tribal council, and a lawmaker. As a warrior, he fought in the C ...

(son of Pathkiller) and Charles R. Hicks

Charles Renatus Hicks (December 23, 1767 – January 20, 1827) (Cherokee) was one of the three most important leaders of his people in the early 19th century, together with James Vann and Major Ridge. The three men all had some European ancestry, ...

, made up the "Cherokee Triumvirate" and became the dominant leaders, particularly of the younger, more acculturated generation. These leaders had had more dealings with European Americans and tended to favor acculturation, formal education, and American methods of farming.

The Cherokee attempted to deal with the United States government as one sovereign and independent nation to another, but they suffered from internal divisions plus encroachment on their land and hostility by white settlers. After several land giveaways by Cherokee leaders acting for their own benefit, the group of "young chiefs," including Ridge and Hicks, arose from 1806-1810 and succeeded in persuading the majority of Cherokees that their survival as a people depended upon unity and tribal ownership of their lands. In 1816-1817, Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

led an effort to force the Cherokee to migrate west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and surrender their lands to the U.S. government. Jackson's attempt led to the Cherokee adopting a political reform that has been called "the first Cherokee constitution." The reform moved away from traditional decision making and decentralized power to establishing a Cherokee nation based on laws, institutions, and centralized authority. The reform also prohibited any additional cession of Cherokee lands to the U.S. government without the consent of a National Committee representing all 54 Cherokee towns.

In 1827 the Cherokees adopted a constitution, similar to that of the U.S., which called for a bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

, an executive

leader, and an independent judiciary. The constitution delineated the boundaries of Cherokee land and, in 1829, the Cherokee government imposed a death penalty on anyone who sold Cherokee land illegally.

The Cherokee continued to be creative. Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

began to develop his writing system, the Cherokee syllabary

The Cherokee syllabary is a syllabary invented by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s to write the Cherokee language. His creation of the syllabary is particularly noteworthy as he was illiterate until the creation of his syllabary. He f ...

, about 1808. He is one of the few individuals from a pre-literate society to create an independent and effective writing system. In the 21st century, carvings representing several symbols of the syllabary were discovered in a Kentucky cave, a sacred site of a burial of a Cherokee chief. A nearby carved date may be 1808 or 1818. Soon after this, Sequoyah moved with his people to Alabama, where he completed his syllabary by 1821 and began to promote it.

Facing removal, members of the Lower Cherokee, who lived in areas of the Piedmont of North Carolina and Georgia, were the first to move west. Remaining Lower Town leaders, such as Young Dragging Canoe and Sequoyah

Sequoyah (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏍᏏᏉᏯ, ''Ssiquoya'', or ᏎᏉᏯ, ''Se-quo-ya''; 1770 – August 1843), also known as George Gist or George Guess, was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American polymath of the Ch ...

, were strong advocates of voluntary relocation in order to preserve the Cherokee people, as they believed that the increasing number of European-American settlers, backed by the military of the US, were too much to resist.

Removal era

In 1815, the US government established a Cherokee Reservation in Arkansas. The reservation boundaries extended from north of theArkansas River

The Arkansas River is a major tributary of the Mississippi River. It generally flows to the east and southeast as it traverses the U.S. states of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. The river's source basin lies in the western United Stat ...

to the southern bank of the White River. The Bowl, Sequoyah, Spring Frog, and Tatsi (Dutch) and their bands settled there. These Cherokee became known as "Old Settlers," or Western Cherokee.

John Ross became the Principal Chief of the tribe in 1828 and remained the chief until he died in Washington, DC in 1866. During the American Civil War, he led the minority group of Cherokee who allied with the Union. He and followers withdrew because of the hostility from Cherokee who allied with the Confederacy.

Treaty party

Among the Cherokee in the early 19th century, John Ross led the battle to resist their removal from their lands in the Southeast. Ross's supporters, commonly referred to as the "National Party," were opposed by a group known as the "Ridge Party" or the "Treaty Party". The Treaty Party, believing that the Cherokee could get the best deal from the US by signing a treaty and negotiating terms, represented the people by signing theTreaty of New Echota

The Treaty of New Echota was a treaty signed on December 29, 1835, in New Echota, Georgia, by officials of the United States government and representatives of a minority Cherokee political faction, the Treaty Party.

The treaty established terms ...

. They believed that removal was finally inevitable, given the numbers and might of the Americans. Among the terms and conditions for removal, they agreed to cede much of the remaining Cherokee lands in the Southeast, in exchange for lands in Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

, plus annuities, supplies and other incentives.

Trail of Tears

Cherokees were displaced from their ancestral lands in northern Georgia and the Carolinas in a period of rapidly expanding white population. Some of the rapid expansion was due to a

Cherokees were displaced from their ancestral lands in northern Georgia and the Carolinas in a period of rapidly expanding white population. Some of the rapid expansion was due to a gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

around Dahlonega, Georgia

The city of Dahlonega () is the county seat of Lumpkin County, Georgia, United States. As of the 2010 census, the city had a population of 5,242, and in 2018 the population was estimated to be 6,884.

Dahlonega is located at the north end of ...

in the 1830s. President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

said removal policy was an effort to prevent the Cherokee from facing extinction, which he said was the fate of "the Mohegan

The Mohegan are an Algonquian Native American tribe historically based in present-day Connecticut. Today the majority of the people are associated with the Mohegan Indian Tribe, a federally recognized tribe living on a reservation in the easte ...

, the Narragansett, and the Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

". There is ample evidence that the Cherokee were adapting modern farming techniques. A late 20th-century analysis shows that their area was in general in a state of economic surplus. Jackson was under immense pressure from European Americans who wanted to take over and exploit the Cherokee lands for themselves.

In June 1830, a delegation of Cherokee led by Chief Ross brought their grievances about tribal sovereignty over state government to the US Supreme Court in the ''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia

''Cherokee Nation v. Georgia'', 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831), was a United States Supreme Court case. The Cherokee Nation sought a federal injunction against laws passed by the U.S. state of Georgia depriving them of rights within its boundaries, but ...

'' case. In the case ''Worcester v. Georgia

''Worcester v. Georgia'', 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832), was a landmark case in which the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court Vacated judgment, vacated the conviction of Samuel Worcester and held that the Georgia criminal ...

'', the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

held that Cherokee Native Americans were entitled to federal protection from the actions of state governments. ''Worcester v. Georgia'' is considered one of the most important decisions in law dealing with Native Americans But the Georgia government essentially ignored it, and removal pressure continued.

The majority of Cherokees were forcibly relocated westward to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in 1838–1839, a migration known as the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

or in Cherokee ᏅᎾ ᏓᎤᎳ ᏨᏱ or ''Nvna Daula Tsvyi'' (Cherokee: The Trail Where They Cried). This took place under the authority of the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830. The harsh treatment the Cherokee received at the hands of white settlers caused some to enroll to emigrate west. As some Cherokees were slaveholders, they took enslaved African-Americans with them west of the Mississippi. Intermarried European-Americans and missionaries also walked the Trail of Tears.

On June 22, 1839, in the Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, Major Ridge, John Ridge and Elias Boudinot

Elias Boudinot ( ; May 2, 1740 – October 24, 1821) was a lawyer and statesman from Elizabeth, New Jersey who was a delegate to the Continental Congress (more accurately referred to as the Congress of the Confederation) and served as Presiden ...

were assassinated by a party of twenty-five Ross supporters. They included Daniel Colston, John Vann, Archibald Spear, James Spear, Joseph Spear, Hunter, and others. They had considered the Treaty of New Echota to be an attempt to sell communal lands, a capital offense. Stand Watie

Brigadier-General Stand Watie ( chr, ᏕᎦᏔᎦ, translit=Degataga, lit=Stand firm; December 12, 1806September 9, 1871), also known as Standhope Uwatie, Tawkertawker, and Isaac S. Watie, was a Cherokee politician who served as the second princ ...

was among the men who were attacked, but he survived and escaped to Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

.

Eastern Band

Some Cherokee in the western area of North Carolina were able to evade removal, and they became the East Band of Cherokee Indians.

Some Cherokee in the western area of North Carolina were able to evade removal, and they became the East Band of Cherokee Indians. William Holland Thomas

William Holland Thomas (February 5, 1805 – May 10, 1893) was an American merchant and soldier.

He was the son of Temperance Thomas (née Colvard) and Richard Thomas, who died before he was born. He was raised by his mother on Raccoon Cr ...

, a white storeowner and state legislator from Jackson County, North Carolina

Jackson County is a county located in the far southwest of the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2020 census, the population was 43,109. Since 1913 its county seat has been Sylva, which replaced Webster.

Jackson County comprises the Cu ...

, helped more than 600 Cherokee from Qualla Town to obtain North Carolina citizenship. As they were willing to give up tribal citizenship, they were exempted from forced removal. Over 400 other Cherokee either hid from Federal troops in the remote Snowbird Mountains, under the leadership of Tsali

Tsali ( chr, ᏣᎵ), originally of Coosawattee Town (''Kusawatiyi''), was a noted leader of the Cherokee during two different periods of the history of the tribe. As a young man, he followed the Chickamauga Cherokee war chief, Dragging Canoe, from ...

(ᏣᎵ),"Tsali."''History and culture of the Cherokee (North Carolina Indians).'' (2007-03-10) or negotiated directly with the state government to stay locally. Many were from the former Valley Towns area around the

Cheoah River

The Cheoah River is a tributary of the Little Tennessee River in North Carolina in the United States.

It is located in Graham County in far western North Carolina, near Robbinsville, and is approximately 20 miles in length. Its headwaters are i ...

. An additional 400 Cherokee stayed on reserves in Southeast Tennessee, North Georgia, and Northeast Alabama, as citizens of their respective states. Many were of mixed-blood or mixed-race descent, and some were Cherokee women married to white men, and their families. Together, these groups were the ancestors of most of the current members of what is now one of three federally recognized Cherokee tribes, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI), (Cherokee language, Cherokee: ᏣᎳᎩᏱ ᏕᏣᏓᏂᎸᎩ, ''Tsalagiyi Detsadanilvgi'') is a Federally recognized tribe, federally recognized Indian Tribe based in Western North Carolina in the U ...

.

Civil War

TheAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...