Cheap talk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Crawford and Sobel characterize possible

Crawford and Sobel characterize possible

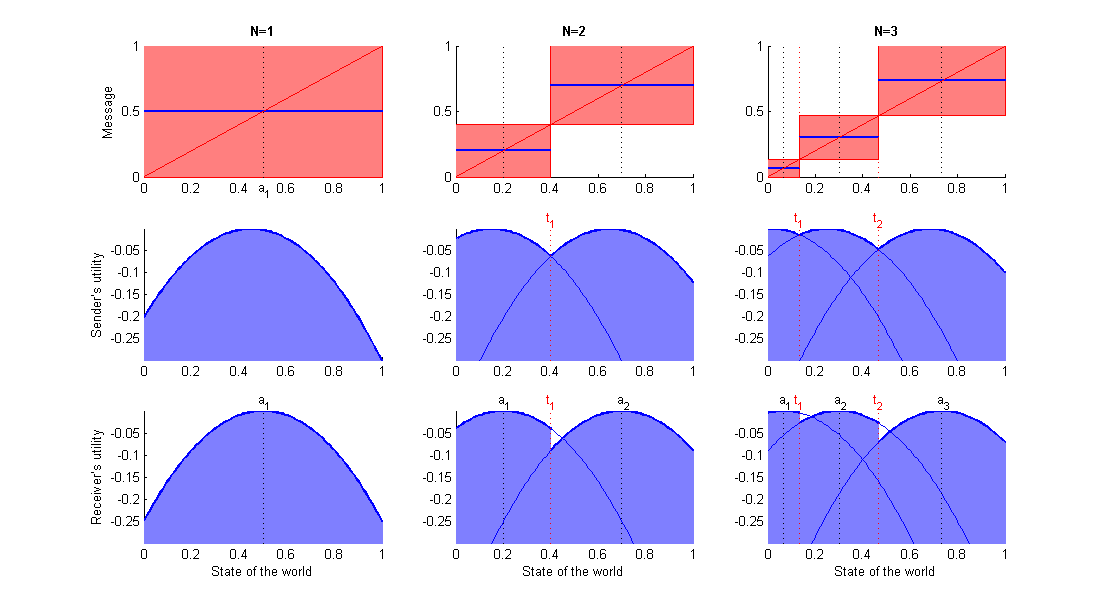

''N = 1:'' This is the babbling equilibrium. ''t0 = 0, t1 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/2 = 0.5''.

''N = 2:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/5 = 0.4, t2 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/5 = 0.2, a2 = 7/10 = 0.7''.

''N = N* = 3:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/15, t2 = 7/15, t3 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/15, a2 = 3/10 = 0.3, a3 = 11/15''.

With ''N = 1'', we get the ''coarsest'' possible message, which does not give any information. So everything is red on the top left panel. With ''N = 3'', the message is ''finer''. However, it remains quite coarse compared to full revelation, which would be the 45° line, but which is not a Nash equilibrium.

With a higher ''N'', and a finer message, the blue area is more important. This implies higher utility. Disclosing more information benefits both parties.

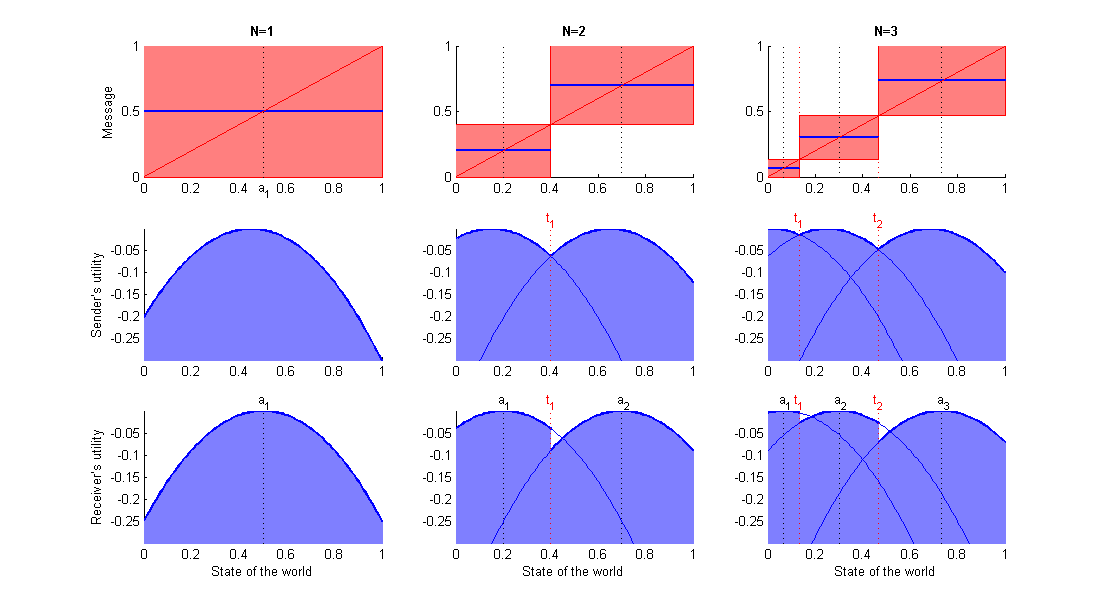

''N = 1:'' This is the babbling equilibrium. ''t0 = 0, t1 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/2 = 0.5''.

''N = 2:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/5 = 0.4, t2 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/5 = 0.2, a2 = 7/10 = 0.7''.

''N = N* = 3:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/15, t2 = 7/15, t3 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/15, a2 = 3/10 = 0.3, a3 = 11/15''.

With ''N = 1'', we get the ''coarsest'' possible message, which does not give any information. So everything is red on the top left panel. With ''N = 3'', the message is ''finer''. However, it remains quite coarse compared to full revelation, which would be the 45° line, but which is not a Nash equilibrium.

With a higher ''N'', and a finer message, the blue area is more important. This implies higher utility. Disclosing more information benefits both parties.

game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions. It has applications in many fields of social science, and is used extensively in economics, logic, systems science and computer science. Initially, game theory addressed ...

, cheap talk is communication between players that does not directly affect the payoffs of the game. Providing and receiving information is free. This is in contrast to signalling

A signal is both the process and the result of transmission of data over some media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processing, information theory and biology.

In ...

, in which sending certain messages may be costly for the sender depending on the state of the world.

This basic setting set by Vincent Crawford and Joel Sobel has given rise to a variety of variants.

To give a formal definition, cheap talk is communication that is:

# costless to transmit and receive

# non-binding (i.e. does not limit strategic choices by either party)

# unverifiable (i.e. cannot be verified by a third party like a court)

Therefore, an agent engaging in cheap talk could lie with impunity, but may choose in equilibrium not to do so.

Applications

Game theory

Cheap talk can, in general, be added to any game and has the potential to enhance the set of possible equilibrium outcomes. For example, one can add a round of cheap talk in the beginning of the game Battle of the Sexes, a game in which each player announces whether they intend to go to the football game, or the opera. Because the Battle of the Sexes is acoordination game

A coordination game is a type of simultaneous game found in game theory. It describes the situation where a player will earn a higher payoff when they select the same course of action as another player. The game is not one of pure conflict, which ...

, this initial round of communication may enable the players to select among multiple equilibria, thereby achieving higher payoffs than in the uncoordinated case. The messages and strategies which yield this outcome are symmetric for each player. One strategy is to announce opera or football with even probability; another is to listen to whether a person announces opera (or football), and on hearing this message say opera (or football) as well. If both players announce different options, then no coordination is achieved. In the case of only one player messaging, this could also give that player a first-mover advantage.

It is not guaranteed, however, that cheap talk will have an effect on equilibrium payoffs. Another game, the Prisoner's Dilemma

The prisoner's dilemma is a game theory thought experiment involving two rational agents, each of whom can either cooperate for mutual benefit or betray their partner ("defect") for individual gain. The dilemma arises from the fact that while def ...

, is a game whose only equilibrium is in dominant strategies. Any pre-play cheap talk will be ignored and players will play their dominant strategies (Defect, Defect) regardless of the messages sent.

Biological applications

It has been commonly argued that cheap talk will have no effect on the underlying structure of the game. Inbiology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

authors have often argued that costly signalling best explains signalling between animals (see Handicap principle

The handicap principle is a hypothesis proposed by the Israeli biologist Amotz Zahavi in 1975. It is meant to explain how "signal selection" during mate choice may lead to Signalling theory, "honest" or reliable signalling between male and femal ...

, Signalling theory

Within evolutionary biology, signalling theory is a body of theoretical work examining communication between individuals, both within species and across species. The central question is how organisms with conflicting interests, such as in se ...

). This general belief has been receiving some challenges (see work by Carl Bergstrom and Brian Skyrms

Brian Skyrms (born 1938) is an American philosopher, Distinguished Professor of Logic and Philosophy of Science and Economics at the University of California, Irvine, and a professor of philosophy at Stanford University. He has worked on problem ...

2002, 2004). In particular, several models using evolutionary game theory

Evolutionary game theory (EGT) is the application of game theory to evolving populations in biology. It defines a framework of contests, strategies, and analytics into which Darwinism, Darwinian competition can be modelled. It originated in 1973 wi ...

indicate that cheap talk can have effects on the evolutionary dynamics of particular games.

Crawford and Sobel's definition

Setting

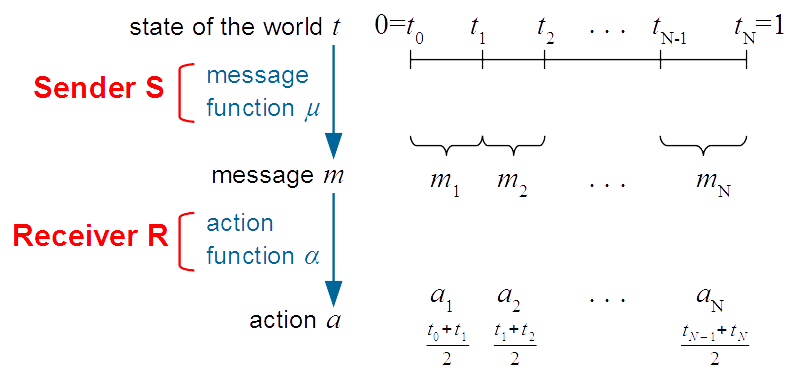

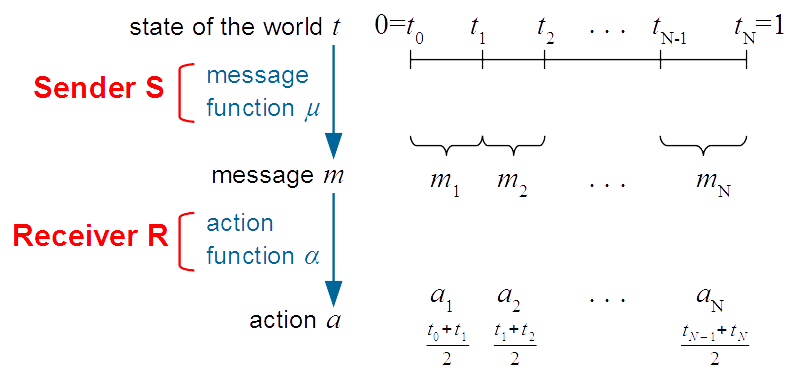

In the basic form of the game, there are two players communicating, one sender ''S'' and one receiver ''R''.Type

Sender ''S'' gets knowledge of the state of the world or of his "type" ''t''. Receiver ''R'' does not know ''t'' ; he has only ex-ante beliefs about it, and relies on a message from ''S'' to possibly improve the accuracy of his beliefs.Message

''S'' decides to send message ''m''. Message ''m'' may disclose full information, but it may also give limited, blurred information: it will typically say "The state of the world is between ''t1'' and ''t2''". It may give no information at all. The form of the message does not matter, as long as there is mutual understanding, common interpretation. It could be a general statement from a central bank's chairman, a political speech in any language, etc. Whatever the form, it is eventually taken to mean "The state of the world is between ''t1'' and ''t2''".Action

Receiver ''R'' receives message ''m''. ''R'' updates his beliefs about the state of the world given new information that he might get, using Bayes's rule. ''R'' decides to take action ''a''. This action impacts both his own utility and the sender's utility.Utility

The decision of ''S'' regarding the content of ''m'' is based on maximizing his utility, given what he expects ''R'' to do. Utility is a way to quantify satisfaction or wishes. It can be financial profits, or non-financial satisfaction—for instance the extent to which the environment is protected. ''→ Quadratic utilities:'' The respective utilities of ''S'' and ''R'' can be specified by the following: The theory applies to more general forms of utility, but quadratic preferences makes exposition easier. Thus ''S'' and ''R'' have different objectives if ''b ≠ 0''. Parameter ''b'' is interpreted as ''conflict of interest'' between the two players, or alternatively as bias.''UR'' is maximized when ''a = t'', meaning that the receiver wants to take action that matches the state of the world, which he does not know in general. ''US'' is maximized when ''a = t + b'', meaning that ''S'' wants a slightly higher action to be taken, if ''b > 0''. Since ''S'' does not control action, ''S'' must obtain the desired action by choosing what information to reveal. Each player's utility depends on the state of the world and on both players' decisions that eventually lead to action ''a''.Nash equilibrium

We look for an equilibrium where each player decides optimally, assuming that the other player also decides optimally. Players are rational, although ''R'' has only limited information. Expectations get realized, and there is no incentive to deviate from this situation.Theorem

Crawford and Sobel characterize possible

Crawford and Sobel characterize possible Nash equilibria

In game theory, the Nash equilibrium is the most commonly used solution concept for non-cooperative games. A Nash equilibrium is a situation where no player could gain by changing their own strategy (holding all other players' strategies fixed) ...

.

* There are typically multiple equilibria, but in a finite number.

* Separating, which means full information revelation, is not a Nash equilibrium.

* Babbling, which means no information transmitted, is always an equilibrium outcome.

When interests are aligned, then information is fully disclosed. When conflict of interest is very large, all information is kept hidden. These are extreme cases. The model allowing for more subtle case when interests are close, but different and in these cases optimal behavior leads to some but not all information being disclosed, leading to various kinds of carefully worded sentences that we may observe.

More generally:

*There exists ''N* > 0'' such that for all ''N'' with ''1 ≤ N ≤ N*'',

*there exists at least an equilibrium in which the set of induced actions has cardinality ''N''; and moreover

*there is no equilibrium that induces more than ''N*'' actions.

Messages

While messages could ex-ante assume an infinite number of possible values ''μ(t)'' for the infinite number of possible states of the world ''t'', actually they may take only a finite number of values ''(m1, m2, . . . , mN)''. Thus an equilibrium may be characterized by a partition ''(t0(N), t1(N). . . tN(N))'' of the set of types, 1

The comma is a punctuation mark that appears in several variants in different languages. Some typefaces render it as a small line, slightly curved or straight, but inclined from the vertical; others give it the appearance of a miniature fille ...

where ''0 = t0(N) < t1(N) < . . . < tN(N) = 1''. This partition is shown on the top right segment of Figure 1.

The ''ti(N)''s are the bounds of intervals where the messages are constant: for ''ti-1(N) < t < ti(N), μ(t) = mi''.

Actions

Since actions are functions of messages, actions are also constant over these intervals: for ''ti-1(N) < t < ti(N)'', ''α(t) = α(mi) = ai''. The action function is now indirectly characterized by the fact that each value ''ai'' optimizes return for the ''R'', knowing that ''t'' is between ''t1'' and ''t2''. Mathematically (assuming that ''t'' is uniformly distributed over, 1

The comma is a punctuation mark that appears in several variants in different languages. Some typefaces render it as a small line, slightly curved or straight, but inclined from the vertical; others give it the appearance of a miniature fille ...

,

→ ''Quadratic utilities:''

Given that ''R'' knows that ''t'' is between ''ti-1'' and ''ti'', and in the special case quadratic utility where ''R'' wants action ''a'' to be as close to ''t'' as possible, we can show that quite intuitively the optimal action is the middle of the interval:

Indifference condition

At , The sender has to be indifferent between sending either message or . ''1 ≤ i≤ N-1'' This gives information about ''N'' and the ''ti''. ''→ Practically:'' We consider a partition of size ''N''. One can show that ''N'' must be small enough so that the numerator is positive. This determines the maximum allowed value where is the ceiling of , i.e. the smallest positive integer greater or equal to . Example: We assume that ''b = 1/20''. Then ''N* = 3''. We now describe all the equilibria for ''N=1'', ''2'', or ''3'' (see Figure 2). ''N = 1:'' This is the babbling equilibrium. ''t0 = 0, t1 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/2 = 0.5''.

''N = 2:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/5 = 0.4, t2 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/5 = 0.2, a2 = 7/10 = 0.7''.

''N = N* = 3:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/15, t2 = 7/15, t3 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/15, a2 = 3/10 = 0.3, a3 = 11/15''.

With ''N = 1'', we get the ''coarsest'' possible message, which does not give any information. So everything is red on the top left panel. With ''N = 3'', the message is ''finer''. However, it remains quite coarse compared to full revelation, which would be the 45° line, but which is not a Nash equilibrium.

With a higher ''N'', and a finer message, the blue area is more important. This implies higher utility. Disclosing more information benefits both parties.

''N = 1:'' This is the babbling equilibrium. ''t0 = 0, t1 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/2 = 0.5''.

''N = 2:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/5 = 0.4, t2 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/5 = 0.2, a2 = 7/10 = 0.7''.

''N = N* = 3:'' ''t0 = 0, t1 = 2/15, t2 = 7/15, t3 = 1''; ''a1 = 1/15, a2 = 3/10 = 0.3, a3 = 11/15''.

With ''N = 1'', we get the ''coarsest'' possible message, which does not give any information. So everything is red on the top left panel. With ''N = 3'', the message is ''finer''. However, it remains quite coarse compared to full revelation, which would be the 45° line, but which is not a Nash equilibrium.

With a higher ''N'', and a finer message, the blue area is more important. This implies higher utility. Disclosing more information benefits both parties.

See also

* Costly signaling theory in evolutionary psychology *Game theory

Game theory is the study of mathematical models of strategic interactions. It has applications in many fields of social science, and is used extensively in economics, logic, systems science and computer science. Initially, game theory addressed ...

*Handicap principle

The handicap principle is a hypothesis proposed by the Israeli biologist Amotz Zahavi in 1975. It is meant to explain how "signal selection" during mate choice may lead to Signalling theory, "honest" or reliable signalling between male and femal ...

*Screening game

A screening game is a two-player principal–agent type game used in economic and game theoretical modeling. Principal–agent problems are situations where there are two players whose interests are not necessarily matching with each other, and ...

*Signaling game

In game theory, a signaling game is a type of a dynamic game, dynamic Bayesian game.Subsection 8.2.2 in Fudenberg Trole 1991, pp. 326–331

The essence of a signaling game is that one player takes action, the signal, to convey information to anot ...

Notes

References

* * * * * {{Game theory Game theory Asymmetric information Strategy (game theory)