Charlie Duke on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Charles Moss Duke Jr. (born October 3, 1935) is an American former

As a boy, Duke and his brother Bill made model aircraft. A congenital heart defect caused Bill to drop out of strenuous sports, and eventually inspired him to pursue a career in medicine, but

As a boy, Duke and his brother Bill made model aircraft. A congenital heart defect caused Bill to drop out of strenuous sports, and eventually inspired him to pursue a career in medicine, but

Duke made the list of 44 finalists selected to undergo medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base at

Duke made the list of 44 finalists selected to undergo medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base at

The Nineteen were divided into command and service module (CSM) and

The Nineteen were divided into command and service module (CSM) and

The next rung on the ladder after serving on a support crew was to serve on a backup crew. The pace of the early Apollo missions meant that multiple crews had to be training at the same time. Slayton developed a rotation scheme whereby the backup crew for one mission would become the prime crew for one three missions later, and then the backup for the one three missions after that. If the commander (CDR) declined the offer of another mission, the command module pilot (CMP), as the next most senior astronaut, would become the commander (CDR). Thus, the Apollo 10 crew became the backup crew for

The next rung on the ladder after serving on a support crew was to serve on a backup crew. The pace of the early Apollo missions meant that multiple crews had to be training at the same time. Slayton developed a rotation scheme whereby the backup crew for one mission would become the prime crew for one three missions later, and then the backup for the one three missions after that. If the commander (CDR) declined the offer of another mission, the command module pilot (CMP), as the next most senior astronaut, would become the commander (CDR). Thus, the Apollo 10 crew became the backup crew for

With the preparations finished, Young and Duke undocked ''Orion'' from Mattingly in the CSM ''Casper''. Mattingly prepared to shift ''Casper'' to a circular orbit while Young and Duke prepared ''Orion'' for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, a malfunction occurred in the engine's backup system, causing such severe oscillations that ''Casper'' seemed to be shaking itself to pieces. According to mission rules, ''Orion'' should have then re-docked with ''Casper'' in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use ''Orion''s engines for the return trip to Earth. This was not done, and the two spacecraft flew on in formation. A decision to land had to be made within five orbits (about ten hours), after which the spacecraft would have drifted too far to reach the landing site.

With the preparations finished, Young and Duke undocked ''Orion'' from Mattingly in the CSM ''Casper''. Mattingly prepared to shift ''Casper'' to a circular orbit while Young and Duke prepared ''Orion'' for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, a malfunction occurred in the engine's backup system, causing such severe oscillations that ''Casper'' seemed to be shaking itself to pieces. According to mission rules, ''Orion'' should have then re-docked with ''Casper'' in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use ''Orion''s engines for the return trip to Earth. This was not done, and the two spacecraft flew on in formation. A decision to land had to be made within five orbits (about ten hours), after which the spacecraft would have drifted too far to reach the landing site.

On the way back to Earth, Duke assisted in a deep-space EVA that lasted 1 hour and 23 minutes, when Mattingly climbed out of the ''Casper'' spacecraft and retrieved film cassettes from the service module. After a journey during which ''Casper'' had traveled , the Apollo 16 mission concluded with a

On the way back to Earth, Duke assisted in a deep-space EVA that lasted 1 hour and 23 minutes, when Mattingly climbed out of the ''Casper'' spacecraft and retrieved film cassettes from the service module. After a journey during which ''Casper'' had traveled , the Apollo 16 mission concluded with a

In 1973, Duke received an

In 1973, Duke received an

astronaut

An astronaut (from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'star', and (), meaning 'sailor') is a person trained, equipped, and deployed by a human spaceflight program to serve as a commander or crew member aboard a spacecraft. Although generally r ...

, United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

(USAF) officer and test pilot

A test pilot is an aircraft pilot with additional training to fly and evaluate experimental, newly produced and modified aircraft with specific maneuvers, known as flight test techniques.Stinton, Darrol. ''Flying Qualities and Flight Testing ...

. As Lunar Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

pilot of Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

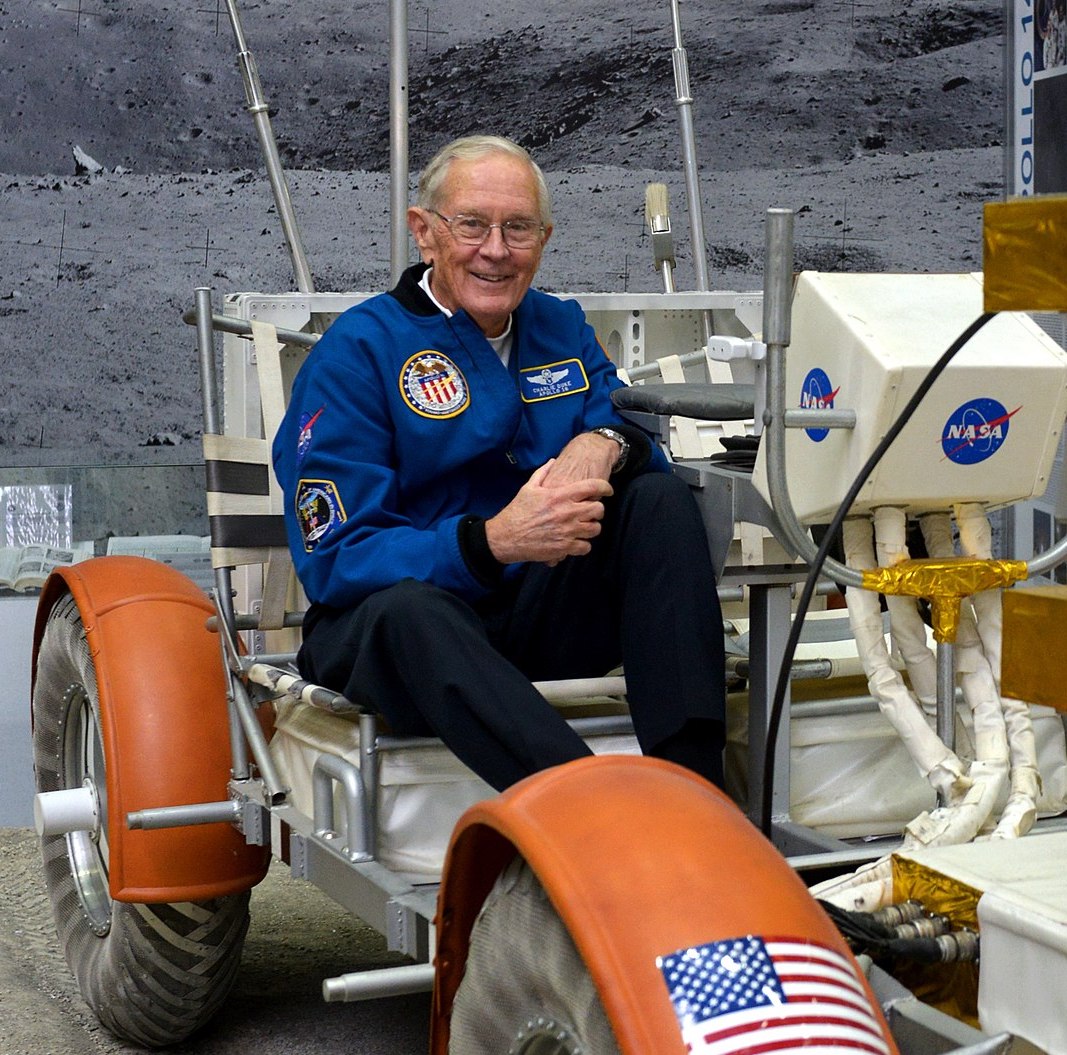

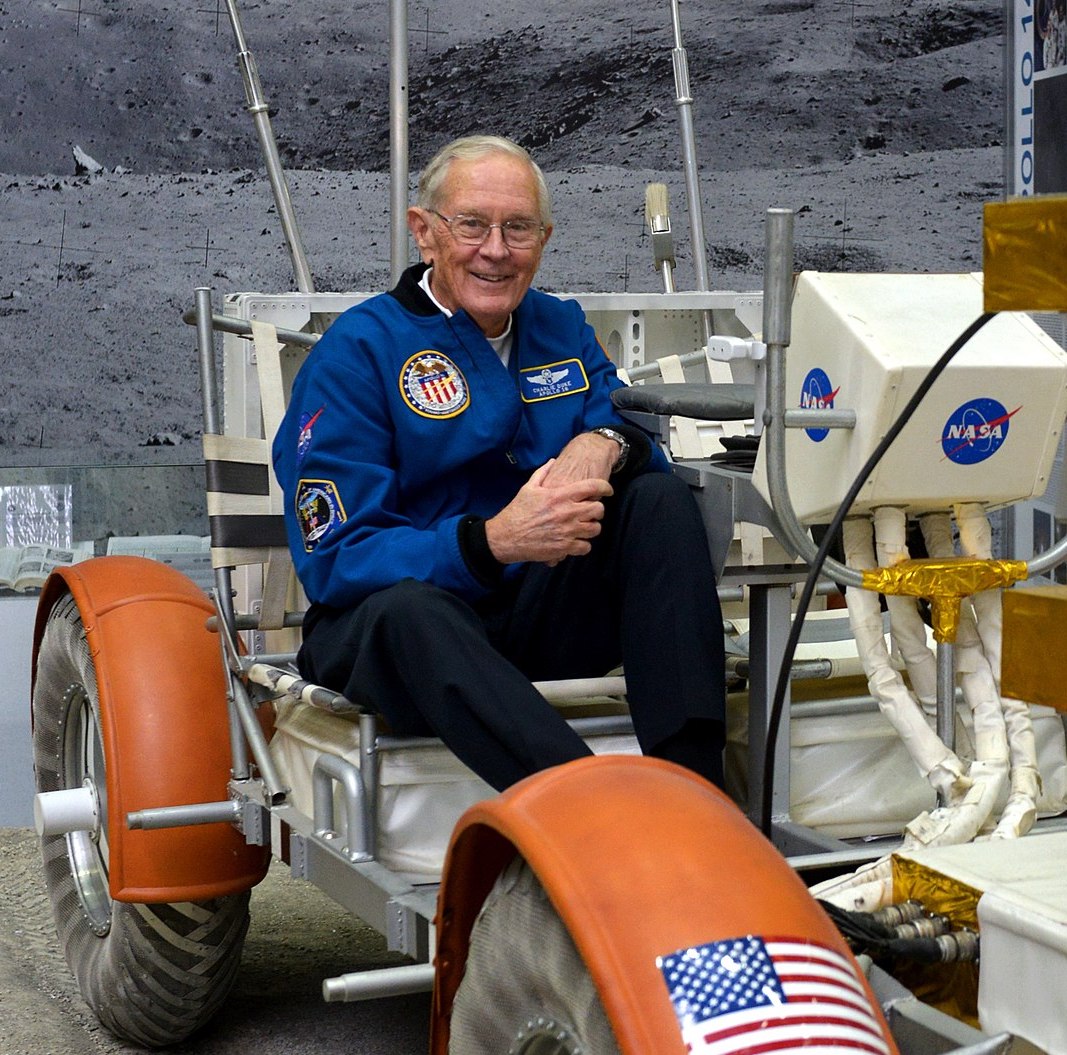

in 1972, he became the tenth and youngest person to walk on the Moon, at age 36 years and 201 days. Duke remains the youngest person to walk on the Moon.

A 1957 graduate of the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, he joined the USAF. He completed advanced flight training on the F-86 Sabre at Moody Air Force Base

Moody Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation near Valdosta, Georgia.

Geography

The base is in northeastern Lowndes County, Georgia, with the eastern border of the base following the Lanier County line. Georgia State Rout ...

in Georgia, where he was a distinguished graduate. After completion of this training, Duke served three years as a fighter pilot with the 526th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron

The 526th Fighter Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was with the 86th Operations Group, based at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. It was inactivated on 1 July 1994.

History

World War II

Initially activated ...

at Ramstein Air Base

Ramstein Air Base or Ramstein AB is a United States Air Force base in Rhineland-Palatinate, a state in southwestern Germany. It serves as headquarters for the United States Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa (USAFE-AFAFRICA) and also ...

in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. After graduating from the Aerospace Research Pilot School in September 1965, he stayed on as an instructor teaching control systems and flying in the F-101 Voodoo, F-104 Starfighter

The Lockheed F-104 Starfighter is an American single-engine, supersonic air superiority fighter which was extensively deployed as a fighter-bomber during the Cold War. Created as a day fighter by Lockheed as one of the "Century Series" of fi ...

, and T-33 Shooting Star

The Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star (or T-Bird) is an American subsonic jet trainer. It was produced by Lockheed and made its first flight in 1948. The T-33 was developed from the Lockheed P-80/F-80 starting as TP-80C/TF-80C in development, then d ...

.

In April 1966, Duke was one of nineteen men selected for NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

's fifth group of astronauts. In 1969, he was a member of the astronaut support crew for Apollo 10. He served as CAPCOM

is a Japanese video game developer and video game publisher, publisher. It has created a number of List of best-selling video game franchises, multi-million-selling game franchises, with its most commercially successful being ''Resident Evil' ...

for Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, an ...

, the first crewed landing on the Moon. His distinctive Southern drawl

A drawl is a perceived feature of some varieties of spoken English and generally indicates slower, longer vowel sounds and diphthongs. The drawl is often perceived as a method of speaking more slowly and may be erroneously attributed to laziness ...

became familiar to audiences around the world, as the voice of a Mission Control made nervous by a long landing that almost expended all of the Lunar Module ''Eagle'' descent stage's propellant. Duke's first words to the Apollo 11 crew on the surface of the Moon were flustered, "Roger, Twank...Tranquility, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again. Thanks a lot!"

Duke was backup lunar module pilot on Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

. Shortly before the mission, he caught rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and ...

(German measles) from a friend's child and inadvertently exposed the prime crew to the disease. As Ken Mattingly had no natural immunity to the disease, he was replaced as command module pilot by Jack Swigert

John Leonard Swigert Jr. (August 30, 1931 – December 27, 1982) was an American NASA astronaut, test pilot, mechanical engineer, aerospace engineer, United States Air Force pilot, and politician. In April 1970, as command module pilot of Apollo ...

. Mattingly was reassigned as command module pilot of Duke's flight, Apollo 16. On this mission, Duke and John Young John Young may refer to:

Academics

* John Young (professor of Greek) (died 1820), Scottish professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow

* John C. Young (college president) (1803–1857), American educator, pastor, and president of Centre Coll ...

landed at the Descartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after whi ...

, and conducted three extravehicular activities (EVAs). He also served as backup lunar module pilot for Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on ...

. Duke retired from NASA on January 1, 1976.

Following his retirement from NASA, Duke entered the Air Force Reserve

The Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) is a MAJCOM, major command (MAJCOM) of the United States Air Force, with its headquarters at Robins Air Force Base, Georgia. It is the federal Air Reserve Component (ARC) of the U.S. Air Force, consisting of ...

and served as a mobilization augmentee to the Commander, USAF Basic Military Training Center, and to the Commander, USAF Recruiting Service. He graduated from the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in 1978. He was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

in 1979, and retired in June 1986. He has logged 4,147 hours' flying time, of which 3,632 hours were in jet aircraft, and 265 hours were in space, including 21 hours and 38 minutes of EVA.

Duke resides in New Braunfels, Texas, and was named Texan of the Year in 2020. He is currently on the board of directors for the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation and previously served for two years as the chairman. He is a popular motivational speaker, with NASA films and personal stories of his Apollo mission on the moon. He is a born-again Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and he and his wife Dorothy speak to audiences regarding their faith and its effect on their marriage.

Early life and education

Charles Moss Duke Jr. was born inCharlotte, North Carolina

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

, on October 3, 1935, the son of Charles Moss Duke, an insurance salesman, and his wife Willie Catherine Waters, who worked as a buyer for Best & Co. He was followed six minutes later by his identical twin brother William Waters (Bill) Duke. His mother traced her ancestry back to Colonel Philemon Waters, who fought in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ju ...

on December 7, 1941, brought the United States into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, his father volunteered to join the Navy, and was assigned to Naval Air Station North Island

Naval Air Station North Island or NAS North Island , at the north end of the Coronado peninsula on San Diego Bay in San Diego, California, is part of the largest aerospace-industrial complex in the United States Navy – Naval Base Coronado (N ...

in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. The family moved to California to join him, but after a year he was shipped out to the South Pacific, and Willie took the boys to Johnston, South Carolina, where her mother lived. His father returned from the South Pacific in 1944, and was stationed at Naval Air Station Daytona Beach

Daytona Beach International Airport is a county-owned airport located three miles (5 km) southwest of Daytona Beach, next to Daytona International Speedway, in Volusia County, Florida, United States. The airport has 3 runways, a six-gate dom ...

, so the family moved there. In 1946, after the war ended, they settled in Lancaster, South Carolina, where his father sold insurance, and his mother ran a dress shop. A sister, Elizabeth (Betsy), was born in 1949.

As a boy, Duke and his brother Bill made model aircraft. A congenital heart defect caused Bill to drop out of strenuous sports, and eventually inspired him to pursue a career in medicine, but

As a boy, Duke and his brother Bill made model aircraft. A congenital heart defect caused Bill to drop out of strenuous sports, and eventually inspired him to pursue a career in medicine, but golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

was a sport that they enjoyed together. Duke was active in the Boy Scouts of America

The Boy Scouts of America (BSA, colloquially the Boy Scouts) is one of the largest scouting organizations and one of the largest youth organizations in the United States, with about 1.2 million youth participants. The BSA was founded i ...

and earned its highest rank, Eagle Scout

Eagle Scout is the highest achievement or rank attainable in the Scouts BSA program of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Since its inception in 1911, only four percent of Scouts have earned this rank after a lengthy review process. The Eagle Sc ...

in 1946. He attended Lancaster High School. Duke decided that he would like to pursue a military career. Since his father had served in the Navy, he wanted to go to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

.

As a first step, Duke went to see his local congressman

A Member of Congress (MOC) is a person who has been appointed or elected and inducted into an official body called a congress, typically to represent a particular constituency in a legislature. The term member of parliament (MP) is an equivalen ...

, James P. Richards

James Prioleau "Dick" Richards (August 31, 1894 – February 21, 1979) was a lawyer, judge, and Democratic Party (United States), Democrat United States House of Representatives, U.S. Representative from South Carolina between 1933 and 1957. H ...

, who lived in Lancaster. Richards said that he would be pleased to give Duke his nomination, as a local boy. Richards advised Duke that he would still need to pass the entrance examination, and recommended that he attend a military prep school

Preparatory school or prep school may refer to: Schools

*Preparatory school (United Kingdom), an independent school preparing children aged 8–13 for entry into fee-charging independent schools, usually public schools

*College-preparatory school, ...

. Duke and his parents accepted this advice, and chose the Admiral Farragut Academy

Admiral Farragut Academy, established in 1933, is a private, College-preparatory school, college-prep school serving students in grades K–12, K-12. Farragut is located in St. Petersburg, Florida in Pinellas County and is surrounded by the comm ...

in St. Petersburg, Florida

St. Petersburg is a city in Pinellas County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 258,308, making it the fifth-most populous city in Florida and the second-largest city in the Tampa Bay Area, after Tampa. It is the ...

, for his final two years of schooling. Duke sat the examination for Annapolis in the middle of his senior

Senior (shortened as Sr.) means "the elder" in Latin and is often used as a suffix for the elder of two or more people in the same family with the same given name, usually a parent or grandparent. It may also refer to:

* Senior (name), a surname ...

year, and soon after received a letter informing him that he had passed, and had been accepted into the class of 1957. The ''Lancaster News'' ran his picture on the front page along with the announcement of his acceptance. He graduated from Farragut as valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

and president of the senior class in 1953.

Duke entered the Naval Academy in June 1953. He was no athlete, but played golf for the academy team. During a two-month summer cruise to Europe on the escort carrier

The escort carrier or escort aircraft carrier (U.S. hull classification symbol CVE), also called a "jeep carrier" or "baby flattop" in the United States Navy (USN) or "Woolworth Carrier" by the Royal Navy, was a small and slow type of aircraft ...

, he suffered from seasickness, and began questioning his decision to join the Navy. On the other hand, he greatly enjoyed a familiarization flight in an N3N

The Naval Aircraft Factory N3N was an American tandem-seat, open cockpit, primary training biplane aircraft built by the Naval Aircraft Factory (NAF) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the 1930s and early 1940s.

Development and design

Built t ...

seaplane, and began thinking of a career in aviation. The United States Air Force Academy

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) is a United States service academy in El Paso County, Colorado, immediately north of Colorado Springs. It educates cadets for service in the officer corps of the United States Air Force and Uni ...

had just been established and would not graduate its first class until 1959, so up to a quarter of the Annapolis class were permitted to volunteer for the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

. In fact, more than a quarter of the class of 1957 did so, and names were drawn from a hat. At his commissioning physical, Duke was shocked to find that he had a minor astigmatism in his right eye, which precluded him from becoming a naval aviator

Naval aviation is the application of military air power by navies, whether from warships that embark aircraft, or land bases.

Naval aviation is typically projected to a position nearer the target by way of an aircraft carrier. Carrier-based a ...

, but the Air Force said that it would still take him. He received a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

degree in naval sciences in June 1957, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in the Air Force.

Air Force

In July 1957, Duke, along with the other graduates of Annapolis andWest Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

who had chosen the Air Force, reported to Maxwell Air Force Base

Maxwell Air Force Base , officially known as Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, is a United States Air Force (USAF) installation under the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The installation is located in Montgomery, Alabama, United States. O ...

in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

, for two weeks' orientation. He was then sent to Spence Air Force Base in Moultrie, Georgia, for primary flight training. The first three months involved classwork and training with the T-34 Mentor

The Beechcraft T-34 Mentor is an American propeller-driven, single-engined, military trainer aircraft derived from the Beechcraft Model 35 Bonanza. The earlier versions of the T-34, dating from around the late 1940s to the 1950s, were piston- ...

, while the next three were with the T-28 Trojan

The North American Aviation T-28 Trojan is a radial-engine military trainer aircraft manufactured by North American Aviation and used by the United States Air Force and United States Navy beginning in the 1950s. Besides its use as a trainer, ...

; both were propeller-driven aircraft. For the next phase of his training, he went to Webb Air Force Base

Webb Air Force Base , previously named Big Spring Air Force Base, was a United States Air Force facility of the Air Training Command that operated from 1951 to 1977 in West Texas within the current city limits of Big Spring. Webb AFB was a maj ...

in Big Spring, Texas

Big Spring is a city in and the county seat of Howard County, Texas, United States, at the crossroads of U.S. Highway 87 and Interstate 20. With a population of 27,282 as of the 2010 census, it is the largest city between Midland to the west, A ...

, in March 1958 for training with the T-33 Shooting Star

The Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star (or T-Bird) is an American subsonic jet trainer. It was produced by Lockheed and made its first flight in 1948. The T-33 was developed from the Lockheed P-80/F-80 starting as TP-80C/TF-80C in development, then d ...

, a jet aircraft. He graduated near the top of his class, and received his wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

and a certificate identifying him as a distinguished graduate, which gave him a choice of assignments. He chose to become a fighter pilot. He completed six months' advanced training on the F-86 Sabre aircraft at Moody Air Force Base

Moody Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation near Valdosta, Georgia.

Geography

The base is in northeastern Lowndes County, Georgia, with the eastern border of the base following the Lanier County line. Georgia State Rout ...

in Valdosta, Georgia

Valdosta is a city in and the county seat of Lowndes County, Georgia, Lowndes County, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia, United States. As of 2019, Valdosta had an estimated population of 56,457.

Valdosta is the principal city of the Valdosta Metr ...

, where he was also a distinguished graduate.

Once again, Duke had his choice of assignments, and chose the 526th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron

The 526th Fighter Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was with the 86th Operations Group, based at Ramstein Air Base, Germany. It was inactivated on 1 July 1994.

History

World War II

Initially activated ...

at Ramstein Air Base

Ramstein Air Base or Ramstein AB is a United States Air Force base in Rhineland-Palatinate, a state in southwestern Germany. It serves as headquarters for the United States Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa (USAFE-AFAFRICA) and also ...

in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

. This was at the height of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, and tensions ran high, especially during the Berlin Crisis of 1961

The Berlin Crisis of 1961 (german: Berlin-Krise) occurred between 4 June – 9 November 1961, and was the last major European politico-military incident of the Cold War about the occupational status of the German capital city, Berlin, and of po ...

. Duke chose the assignment precisely because it was the front line. Four of the 526th's F-86 (and later F-102 Delta Dagger

The Convair F-102 Delta Dagger was an American interceptor aircraft designed and manufactured by Convair.

Built as part of the backbone of the United States Air Force's air defenses in the late 1950s, it entered service in 1956. Its main purpos ...

) fighter-interceptors were always on alert, ready to scramble and intercept aircraft crossing the border from East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

.

As his three-year tour of duty in Europe came to an end, Duke considered that his best career option was to further his education, something that the USAF was encouraging. He applied to study aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: Aeronautics, aeronautical engineering and Astronautics, astronautical engineering. A ...

at North Carolina State University

North Carolina State University (NC State) is a public land-grant research university in Raleigh, North Carolina. Founded in 1887 and part of the University of North Carolina system, it is the largest university in the Carolinas. The universit ...

, but this was not available. Instead, he was offered a place at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

(MIT) in its Master of Science

A Master of Science ( la, Magisterii Scientiae; abbreviated MS, M.S., MSc, M.Sc., SM, S.M., ScM or Sc.M.) is a master's degree in the field of science awarded by universities in many countries or a person holding such a degree. In contrast to ...

degree course in aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design, and manufacturing of air flight–capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere. The British Royal Aeronautical Society identifies ...

and astronautics. He entered MIT in June 1962.

It was in Boston that he met Dotty Meade Claiborne, a graduate of Hollins College and the University of North Carolina

The University of North Carolina is the multi-campus public university system for the state of North Carolina. Overseeing the state's 16 public universities and the NC School of Science and Mathematics, it is commonly referred to as the UNC Sy ...

, who had recently returned from a summer trip to Europe. They became engaged on Christmas Day

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year, ...

, 1962, and were married by her uncle, Randolph Claiborne, the bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

of the Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta

The Episcopal Diocese of Atlanta is the diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, with jurisdiction over middle and north Georgia. It is in Province IV of the Episcopal Church and its cathedral, the Cathedral of St. Phi ...

, in the Cathedral of Saint Philip, on June 1, 1963. They went to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

for their honeymoon, but came down with food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the spoilage of contaminated food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites that contaminate food,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease) ...

.

While he was courting Dotty, Duke's grades had slipped, and he was placed on scholastic probation

Academic probation, sometimes known as flunking out, is the formal warning that is given to students at a higher educational institution as the result of poor academic achievement. Normally, if students that are on academic probation does not quic ...

, but the USAF allowed him to enroll for another term. For his dissertation, Duke teamed up with a classmate, Mike Jones, to perform statistical analysis for the Project Apollo guidance systems. As part of this work, they got to meet astronaut Charles Bassett. Their work earned them an A, bringing his average up to the required B, and he was awarded his Master of Science degree in May 1964.

For his next assignment, Duke applied for the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS), although he felt his chances of admission were slim given that he only barely met the minimum qualification. Nonetheless, orders came through for him to attend class 64-C, which commenced in August 1964 at Edwards Air Force Base

Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) is a United States Air Force installation in California. Most of the base sits in Kern County, but its eastern end is in San Bernardino County and a southern arm is in Los Angeles County. The hub of the base is E ...

in California. The commandant at the time was Chuck Yeager, and Duke's twelve-member class included Spence M. Armstrong, Al Worden

Alfred Merrill Worden (February 7, 1932 – March 18, 2020) was an American test pilot, engineer and NASA astronaut who was the command module pilot for the Apollo 15 lunar mission in 1971. One of only 24 people to have flown to the ...

, Stuart Roosa

Stuart Allen Roosa (August 16, 1933 – December 12, 1994) was an American aeronautical engineer, smokejumper, United States Air Force Aviator, pilot, test pilot, and NASA astronaut, who was the Apollo Command/Service Module, Command Module Pilo ...

and Hank Hartsfield. Peter Hoag topped the class; Duke tied for second place. After graduating from ARPS in September 1965, Duke stayed on as an instructor teaching control systems and flying in the F-101 Voodoo, F-104 Starfighter

The Lockheed F-104 Starfighter is an American single-engine, supersonic air superiority fighter which was extensively deployed as a fighter-bomber during the Cold War. Created as a day fighter by Lockheed as one of the "Century Series" of fi ...

, and T-33 Shooting Star aircraft. While he was stationed at Edwards, his first child, Charles Moss Duke III, was born at the base hospital in March 1965.

NASA

Selection and training

On September 10, 1965,NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

announced that it was recruiting a fifth group of astronauts. Duke spotted a front-page article in the ''Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

'', and realized that he met all the requirements. He went to see Yeager and the deputy commandant, Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Robert Buchanan, who informed him that there were two astronaut selections in progress: one for NASA, and one for the USAF's Manned Orbiting Laboratory

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) was part of the United States Air Force (USAF) human spaceflight program in the 1960s. The project was developed from early USAF concepts of crewed space stations as reconnaissance satellites, and was a s ...

(MOL) program. Nominations to NASA had to come through Air Force channels, so it got to pre-screen them. Buchanan told Duke that he could apply for both programs, but if he did, MOL would take him. Duke applied only to NASA, as did Roosa and Worden; Hartsfield applied for both and was taken by MOL.

Duke made the list of 44 finalists selected to undergo medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base at

Duke made the list of 44 finalists selected to undergo medical examinations at Brooks Air Force Base at San Antonio, Texas

("Cradle of Freedom")

, image_map =

, mapsize = 220px

, map_caption = Interactive map of San Antonio

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = United States

, subdivision_type1= State

, subdivision_name1 = Texas

, subdivision_t ...

. He arrived there on January 26, 1966, along with two fellow aviators from Edwards, Joe Engle and Bill Pogue. Psychological tests included Rorschach test

The Rorschach test is a projective psychological test in which subjects' perceptions of inkblots are recorded and then analyzed using psychological interpretation, complex algorithms, or both. Some psychologists use this test to examine a pe ...

s; physical ones included encephalogram

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method to record an electrogram of the spontaneous electrical activity of the brain. The biosignals detected by EEG have been shown to represent the postsynaptic potentials of pyramidal neurons in the neocortex ...

s, and sessions on treadmill

A treadmill is a device generally used for walking, running, or climbing while staying in the same place. Treadmills were introduced before the development of powered machines to harness the power of animals or humans to do work, often a type of ...

s and in a human centrifuge. The eye problem that the Naval Academy had reported was not found.

The final stage of the selection process was an interview by the seven-member selection panel. This was chaired by Deke Slayton, with the other members being astronauts Alan Shepard, John Young John Young may refer to:

Academics

* John Young (professor of Greek) (died 1820), Scottish professor of Greek at the University of Glasgow

* John C. Young (college president) (1803–1857), American educator, pastor, and president of Centre Coll ...

, Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

and C.C. Williams, NASA test pilot Warren North, and spacecraft designer Max Faget

Maxime Allen "Max" Faget (pronounced ''fah-ZHAY''; August 26, 1921 – October 9, 2004) was a Belizean-born American mechanical engineer. Faget was the designer of the Mercury spacecraft, and contributed to the later Gemini and Apollo spac ...

. These were conducted over a week at the Rice Hotel in Houston. In April 1966, a phone call from Slayton informed Duke that he had been selected. NASA officially announced the names of the 19 men selected on April 4, 1966. Young named the group the "Original Nineteen" in a parody of the original Mercury Seven astronauts.

Duke and his family moved to an apartment in League City, Texas, but when Dotty became pregnant again, they bought a vacant lot in El Lago, Texas

El Lago is a city in Harris County, Texas, United States. The population was 3,090 at the 2020 census.

El Lago has particular historical significance as it sits on the site of one of the main hide-outs for the French pirate and privateer Jean L ...

, next door to astronaut Bill Anders. They met and befriended a young couple, Glenn and Suzanne House. Glenn was an architect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

, and he agreed to design them a house for $300. Ground was broken in February 1967, but the house was not completed before a second son, Thomas, was born in May.

Astronaut training included four months of studies covering subjects such as astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, orbital mechanics and spacecraft systems. Some 30 hours of briefings were conducted on the Apollo command and service module, and twelve on the Apollo lunar module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

. An important feature was training in geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

, so that astronauts on the Moon would know what rocks to look out for. This training in geology included field trips to the Grand Canyon

The Grand Canyon (, yuf-x-yav, Wi:kaʼi:la, , Southern Paiute language: Paxa’uipi, ) is a steep-sided canyon carved by the Colorado River in Arizona, United States. The Grand Canyon is long, up to wide and attains a depth of over a m ...

and the Meteor Crater

Meteor Crater, or Barringer Crater, is a meteorite impact crater about east of Flagstaff and west of Winslow in the desert of northern Arizona, United States. The site had several earlier names, and fragments of the meteorite are official ...

in Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

, Philmont Scout Ranch

Philmont Scout Ranch is a ranch located in Colfax County, New Mexico, near the village of Cimarron; it covers of wilderness in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains on the east side of the Cimarron Range of the Rocky Mountains. Donated by oil baro ...

in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ker ...

, Horse Lava Tube System

The Horse Lava Tube System (or Horse system) is a series of lava tubes within Deschutes County, Oregon, of the United States. The system starts within the Deschutes National Forest on the northern flank of Newberry Volcano and heads north into a ...

in Bend, Oregon

Bend is a city in and the county seat of Deschutes County, Oregon, United States. It is the principal city of the Bend Metropolitan Statistical Area. Bend is Central Oregon's largest city, with a population of 99,178 at the time of the 2020 U.S ...

, and the ash flow in the Marathon Uplift

The Marathon Uplift is a Paleogene-age domal uplift, approximately in diameter, in southwest Texas. The Marathon Basin was created by erosion of Cretaceous and younger strata from the crest of the uplift.McBride, E.F. and Hayward, O.T., 1988''Ge ...

in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

, and other locations, including Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

and Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

. There was also jungle survival training in Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

, and desert survival training around Reno, Nevada

Reno ( ) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada-California border, about north from Lake Tahoe, known as "The Biggest Little City in the World". Known for its casino and tourism industry, Reno is the ...

. Water survival training was conducted at Naval Air Station Pensacola using the Dilbert Dunker

The Dilbert Dunker is a device for training pilots on how to correctly escape a submerged plane.

It was invented by Ensign Wilfred Kaneb, an aviation engineer at NAS Pensacola, in 1943–1944.

Originally named the "Underwater Cockpit Escape Devi ...

.

Once their initial training was complete, Duke and Roosa were assigned to oversee the development of the Saturn V

Saturn V is a retired American super heavy-lift launch vehicle developed by NASA under the Apollo program for human exploration of the Moon. The rocket was human-rated, with multistage rocket, three stages, and powered with liquid-propellant r ...

launch vehicle, as part of the Booster Branch of the Astronaut Office, headed by Frank Borman and C.C. Williams. He was part of the Mission Control team at the Kennedy Space Center

The John F. Kennedy Space Center (KSC, originally known as the NASA Launch Operations Center), located on Merritt Island, Florida, is one of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's (NASA) ten field centers. Since December 1968 ...

that monitored the launch of Gemini 11 on September 12, 1966, and Gemini 12 on November 11, 1966. His personal responsibility was the Titan II

The Titan II was an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) developed by the Glenn L. Martin Company from the earlier Titan I missile. Titan II was originally designed and used as an ICBM, but was later adapted as a medium-lift space l ...

booster. They frequently traveled to Marshall Space Flight Center

The George C. Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC), located in Redstone Arsenal, Alabama (Huntsville postal address), is the U.S. government's civilian rocketry and spacecraft propulsion research center. As the largest NASA center, MSFC's first ...

in Huntsville, Alabama

Huntsville is a city in Madison County, Limestone County, and Morgan County, Alabama, United States. It is the county seat of Madison County. Located in the Appalachian region of northern Alabama, Huntsville is the most populous city in t ...

, to confer with its director, Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

. NASA provided T-38 Talon

The Northrop T-38 Talon is a two-seat, twinjet supersonic jet trainer. It was the world's first, and the most produced, supersonic trainer. The T-38 remains in service in several air forces.

The United States Air Force (USAF) operates the most ...

aircraft for the astronauts' use, and like most astronauts, Duke flew at every opportunity.

Lunar Module specialist

The Nineteen were divided into command and service module (CSM) and

The Nineteen were divided into command and service module (CSM) and Lunar Module

The Apollo Lunar Module (LM ), originally designated the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM), was the lunar lander spacecraft that was flown between lunar orbit and the Moon's surface during the United States' Apollo program. It was the first crewed ...

(LM) specialists. Slayton asked each of them which specialty he preferred, but made the final decision himself. Once again, Duke received his choice, and became a lunar module specialist. He oversaw the development of the lunar module propulsion systems. A major concern was the ascent propulsion system, which was a critical component of the mission that had to work for the astronauts to survive. Testing at the White Sands Missile Range

White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) is a United States Army military testing area and firing range located in the US state of New Mexico. The range was originally established as the White Sands Proving Ground on 9July 1945. White Sands National P ...

in 1966 indicated combustion instability. George Low, the Apollo Spacecraft Program manager, convened a committee to review the situation, and Duke became the Astronaut Office representative on it. Although Bell was confident that it could resolve the problems, NASA hired Rocketdyne

Rocketdyne was an American rocket engine design and production company headquartered in Canoga Park, California, Canoga Park, in the western San Fernando Valley of suburban Los Angeles, California, Los Angeles, in southern California.

The Rocke ...

to develop an alternative engine just in case. The committee ultimately decided to use Rocketdyne's injector system with Bell's engine.

In 1969, Duke became a member of the support crew for Apollo 10, along with Joe Engle and Jim Irwin

James Benson Irwin (March 17, 1930 – August 8, 1991) was an American astronaut, aeronautical engineer, test pilot, and a United States Air Force pilot. He served as Apollo Lunar Module pilot for Apollo 15, the fourth human lunar landi ...

. During Projects Mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

and Gemini

Gemini may refer to:

Space

* Gemini (constellation), one of the constellations of the zodiac

** Gemini in Chinese astronomy

* Project Gemini, the second U.S. crewed spaceflight program

* Gemini Observatory, consisting of telescopes in the Northern ...

, each mission had a prime and a backup crew. For Apollo, a third crew of astronauts was added, known as the support crew. The support crew maintained the flight plan, checklists and mission ground rules, and ensured the prime and backup crews were apprised of changes. They developed procedures, especially those for emergency situations, so these were ready for when the prime and backup crews came to train in the simulators, allowing them to concentrate on practicing and mastering them. The mission commander, Tom Stafford, selected Duke for his familiarity with the LM, especially its propulsion systems. For this reason, Duke served as CAPCOM

is a Japanese video game developer and video game publisher, publisher. It has created a number of List of best-selling video game franchises, multi-million-selling game franchises, with its most commercially successful being ''Resident Evil' ...

for the LM orbit, activation, checkout, and rendezvous on Apollo 10.

It was unusual for someone to serve as CAPCOM on back-to-back missions, but for the same reason—familiarity with the LM—Neil Armstrong

Neil Alden Armstrong (August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an American astronaut and aeronautical engineer who became the first person to walk on the Moon in 1969. He was also a naval aviator, test pilot, and university professor.

...

, the commander of Apollo 11

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module ''Eagle'' on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, an ...

, asked Duke to reprise his role on that mission, which included the first crewed landing on the Moon. Duke told Armstrong that he would be honored to do so. Duke's distinctive Southern drawl

A drawl is a perceived feature of some varieties of spoken English and generally indicates slower, longer vowel sounds and diphthongs. The drawl is often perceived as a method of speaking more slowly and may be erroneously attributed to laziness ...

became familiar to audiences around the world, as the voice of a Mission Control made nervous by a long landing that almost expended all of the Lunar Module ''Eagle

Eagle is the common name for many large birds of prey of the family Accipitridae. Eagles belong to several groups of genera, some of which are closely related. Most of the 68 species of eagle are from Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just ...

''s fuel. Duke's first words to the Apollo 11 crew on the surface of the Moon were flustered, "Roger, Twank...Tranquility, we copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again. Thanks a lot!"

Apollo 13

The next rung on the ladder after serving on a support crew was to serve on a backup crew. The pace of the early Apollo missions meant that multiple crews had to be training at the same time. Slayton developed a rotation scheme whereby the backup crew for one mission would become the prime crew for one three missions later, and then the backup for the one three missions after that. If the commander (CDR) declined the offer of another mission, the command module pilot (CMP), as the next most senior astronaut, would become the commander (CDR). Thus, the Apollo 10 crew became the backup crew for

The next rung on the ladder after serving on a support crew was to serve on a backup crew. The pace of the early Apollo missions meant that multiple crews had to be training at the same time. Slayton developed a rotation scheme whereby the backup crew for one mission would become the prime crew for one three missions later, and then the backup for the one three missions after that. If the commander (CDR) declined the offer of another mission, the command module pilot (CMP), as the next most senior astronaut, would become the commander (CDR). Thus, the Apollo 10 crew became the backup crew for Apollo 13

Apollo 13 (April 1117, 1970) was the seventh crewed mission in the Apollo space program and the third meant to land on the Moon. The craft was launched from Kennedy Space Center on April 11, 1970, but the lunar landing was aborted aft ...

. Tom Stafford accepted the position of acting Chief of the Astronaut Office, so the CMP, John Young, stepped up to replace him as CDR; Gene Cernan remained lunar module pilot (LMP), and Jack Swigert

John Leonard Swigert Jr. (August 30, 1931 – December 27, 1982) was an American NASA astronaut, test pilot, mechanical engineer, aerospace engineer, United States Air Force pilot, and politician. In April 1970, as command module pilot of Apollo ...

, a command module specialist from the Nineteen, was designated the CMP. The intention was that this crew would eventually become the prime crew for Apollo 16

Apollo 16 (April 1627, 1972) was the tenth crewed mission in the United States Apollo space program, administered by NASA, and the fifth and penultimate to land on the Moon. It was the second of Apollo's " J missions", with an extended sta ...

, but Cernan did not agree with this; he wanted to command his own mission. Slayton therefore assigned Duke, who was well known to Young from Apollo 10, in Cernan's place. After Michael Collins, the CMP of Apollo 11, turned down the offer of command of the backup crew of Apollo 14

Apollo 14 (January 31, 1971February 9, 1971) was the eighth crewed mission in the United States Apollo program, the third to land on the Moon, and the first to land in the lunar highlands. It was the last of the " H missions", landings at s ...

, Slayton gave this command to Cernan.

Full-time training for Apollo 13 commenced in July 1969, although the selection of the Apollo 13 and 14 crews was not officially announced until August 7. The prime crew for Apollo 13 consisted of Jim Lovell (CDR), Fred Haise (LMP) and Ken Mattingly (CMP). The mission was originally scheduled to be flown in late 1969, but in view of the successful outcome of Apollo 11, it was postponed until March and then April 1970. Two or three weeks before the launch date, Duke contracted rubella

Rubella, also known as German measles or three-day measles, is an infection caused by the rubella virus. This disease is often mild, with half of people not realizing that they are infected. A rash may start around two weeks after exposure and ...

(German measles) from Paul House, the son of Glenn and Suzanne House. The disease is highly contagious, so the NASA doctors checked the prime crew. It was found that Lovell and Haise were immune to the disease, but Mattingly was not. The decision was taken to remove Mattingly and replace him with Swigert.

The subsequent explosion on Apollo 13 greatly affected the backup crew, especially Mattingly, who felt that he should have been on board. Young, Mattingly and Duke worked in the simulators to develop emergency procedures for the crew, who were ultimately returned safely to Earth. Haise and Swigert teased Duke, calling him "Typhoid Mary

Mary Mallon (September 23, 1869 – November 11, 1938), commonly known as Typhoid Mary, was an Irish Americans, Irish-born American cook believed to have infected between 51 and 122 people with typhoid fever. The infections caused three co ...

". The measles incident resulted in procedures being changed; starting with Apollo 14, the crew would be quarantined for three weeks before the flight as well as afterward. In the event, only the Apollo 14 crew had to endure two periods of quarantine; with no signs of life on the Moon, the post-mission quarantine was discontinued in April 1971.

Apollo 16

Training

Young, Mattingly and Duke were officially named as the crew of Apollo 16, the fifth lunar landing mission, on March 3, 1971. TheDescartes Highlands

The Descartes Highlands is an area of lunar highlands located on the near side that served as the landing site of the American Apollo 16 mission in early 1972. The Descartes Highlands is located in the area surrounding Descartes crater, after whi ...

were chosen as the landing site on June 3, 1971. This was the highest region on the near side of the Moon. It was believed to be volcanic in origin and mainly composed of basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

, based upon the tones of gray observed from Earth. It was hoped that rock samples retrieved by Apollo 16 would provide clues about the processes that formed the highlands, and perhaps even show that such processes were still active.

Training was conducted in the lunar module simulator, which used a TV camera and a scale model of the landing area. Other activities included driving a training version of the Lunar Roving Vehicle

The Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) is a battery-powered four-wheeled rover used on the Moon in the last three missions of the American Apollo program ( 15, 16, and 17) during 1971 and 1972. It is popularly called the Moon buggy, a play on the t ...

(LRV), and collecting geological samples. A final geological field trip was made to the big island of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii ) is the List of islands of the United States by area, largest island in the United States, located in the U.S. state, state of Hawaii. It is the southeasternmost of the Hawaiian Islands, a chain of High island, volcanic ...

in December 1971. On the second day of the trip, Duke caught the flu

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

. By New Year's Day he was so ill that he was unable to get out of bed, and asked the Astronaut Office to send someone to take him to the doctor at the Kennedy Space Center. The doctor took an X-ray that revealed pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

in both lungs and called an ambulance to take Duke to the Patrick Air Force Base Patrick may refer to:

*Patrick (given name), list of people and fictional characters with this name

*Patrick (surname), list of people with this name

People

*Saint Patrick (c. 385–c. 461), Christian saint

*Gilla Pátraic (died 1084), Patrick or ...

hospital.

Duke feared that he might not recover in time for the launch, which was scheduled for March 17, 1972. The spacecraft and Saturn V launch vehicle had already been rolled out to Launch Pad 39A

Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) is the first of Launch Complex 39's three launch pads, located at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. The pad, along with Launch Complex 39B, were first designed for the Saturn V launch vehicle. Ty ...

on December 13. Luck was with Duke: Grumman engineers wanted more time to test the increased capacity of the LM's batteries; a fault was found with the explosive cords that separate the LM from the CSM that warranted their replacement; and a failure of a clamp in Duke's spacesuit during training required the modification of all three astronauts' suits. This caused the launch date to be postponed to the next launch window, on April 16. This proved fortunate when an error by launch pad technicians caused one of the CM's Teflon fuel tank bladders to rupture, and the entire space vehicle had to be returned to the Vehicle Assembly Building

The Vehicle Assembly Building (originally the Vertical Assembly Building), or VAB, is a large building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC), designed to assemble large pre-manufactured space vehicle components, such as the massive Saturn V and th ...

. Slayton noted that "there wasn't even any discussion of replacing him; that was one of the lessons we'd learned on 13."

The astronauts went into quarantine and were allowed out only to fly T-38s for an hour a day. The day before liftoff, the Apollo Program director, Rocco Petrone

Rocco Anthony Petrone (March 31, 1926 – August 24, 2006) was an American mechanical engineer, U.S. Army officer and NASA official. He served as director of launch operations at NASA's Kennedy Space Center (KSC) from 1966 to 1969, as Apollo ...

saw someone he believed to be Duke around the pool at the Holiday Inn. A furious Petrone called the crew quarters demanding to know why Duke had broken quarantine. The staff's protestations that Duke was still there and had not left did not placate Petrone, and they had to track down Duke in training, who suggested that Petrone might have seen his brother Bill. When Apollo 16 was launched at 12:54 Eastern Standard Time (17:54 UTC) on April 16, 1972, Duke became the first twin to fly in space.

Outbound voyage

The launch was normal; the crew experienced vibration similar to that of previous crews. The first and second stages of the Saturn V performed flawlessly, and the spacecraft enteredlow Earth orbit

A low Earth orbit (LEO) is an orbit around Earth with a period of 128 minutes or less (making at least 11.25 orbits per day) and an eccentricity less than 0.25. Most of the artificial objects in outer space are in LEO, with an altitude never mor ...

just under 12 minutes after liftoff. In Earth orbit, the crew faced minor technical issues, including a potential problem with the environmental control system

In aeronautics, an environmental control system (ECS) of an aircraft is an essential component which provides air supply, Air conditioning, thermal control and cabin pressurization for the Aircrew, crew and passengers. Additional functions incl ...

and the S-IVB

The S-IVB (pronounced "S-four-B") was the third stage on the Saturn V and second stage on the Saturn IB launch vehicles. Built by the Douglas Aircraft Company, it had one J-2 (rocket engine), J-2 rocket engine. For lunar missions it was fired twi ...

third stage's attitude control system, but these were resolved or compensated for. After 1.5 orbits, it reignited for just over five minutes, propelling the craft towards the Moon at .

In lunar orbit, the crew faced a series of problems. Duke was unable to get the S-band steerable antenna on the LM ''Orion'' to move in the yaw axis

An aircraft in flight is free to rotate in three dimensions: '' yaw'', nose left or right about an axis running up and down; ''pitch'', nose up or down about an axis running from wing to wing; and ''roll'', rotation about an axis running from ...

, and therefore could not align it correctly. This resulted in poor communications with the ground stations, and consequently a loss of the computer uplink. This meant that Duke had to copy down 35 five-digit numbers and enter them into the computer. Correcting any mistake was a complicated procedure. Fortunately, the astronauts could still hear Mission Control clearly, although the reverse was not the case.

When Young went to activate the reaction control system

A reaction control system (RCS) is a spacecraft system that uses thrusters to provide attitude control and translation. Alternatively, reaction wheels are used for attitude control. Use of diverted engine thrust to provide stable attitude contr ...

, they suffered a double failure on the pressurization system. Young described this as "the worst jam I was ever in". A long debate between the astronauts and with Mission Control followed. It was the only time during the flight that Duke could recall arguing with Young. Although they could not fix the problem, they were able to work around it by shifting propellant into the ascent storage tank. None was lost; it was just moved into another tank.

With the preparations finished, Young and Duke undocked ''Orion'' from Mattingly in the CSM ''Casper''. Mattingly prepared to shift ''Casper'' to a circular orbit while Young and Duke prepared ''Orion'' for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, a malfunction occurred in the engine's backup system, causing such severe oscillations that ''Casper'' seemed to be shaking itself to pieces. According to mission rules, ''Orion'' should have then re-docked with ''Casper'' in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use ''Orion''s engines for the return trip to Earth. This was not done, and the two spacecraft flew on in formation. A decision to land had to be made within five orbits (about ten hours), after which the spacecraft would have drifted too far to reach the landing site.

With the preparations finished, Young and Duke undocked ''Orion'' from Mattingly in the CSM ''Casper''. Mattingly prepared to shift ''Casper'' to a circular orbit while Young and Duke prepared ''Orion'' for the descent to the lunar surface. At this point, during tests of the CSM's steerable rocket engine in preparation for the burn to modify the craft's orbit, a malfunction occurred in the engine's backup system, causing such severe oscillations that ''Casper'' seemed to be shaking itself to pieces. According to mission rules, ''Orion'' should have then re-docked with ''Casper'' in case Mission Control decided to abort the landing and use ''Orion''s engines for the return trip to Earth. This was not done, and the two spacecraft flew on in formation. A decision to land had to be made within five orbits (about ten hours), after which the spacecraft would have drifted too far to reach the landing site.

Lunar surface

After four hours and three orbits, Mission Control determined that the malfunction could be worked around and told Young and Duke to proceed with the landing. As a result of the delay, powered descent to the lunar surface began about six hours behind schedule, and Young and Duke began their descent to the surface at an altitude higher than normal. At an altitude of about , Young was able to view the landing site in its entirety. ''Orion'' landed on the Cayley Plains, northwest of the planned landing site, at 02:23:35 UTC on April 21. Duke became the tenth person to walk upon the surface of the Moon, following Young, who became the ninth. Apollo 16 was the first scientific expedition to inspect, survey, and sample materials and surface features in the rugged lunar highlands. In a stay of 71 hours and 14 minutes, Duke and Young conducted three excursions onto the lunar surface, during which Duke logged 20 hours and 15 minutes in extravehicular activities. These included the emplacement and activation of scientific equipment and experiments, the collection of nearly of rock and soil samples, and the evaluation and use of the LRV over the roughest surface yet encountered on the Moon. During their final few minutes on the surface, Duke attempted to set a lunar high jump record. He jumped about , but overbalanced, and fell over backwards on his primary life support system (PLSS). It could have been a fatal accident; had his suit ruptured or PLSS broken, he might have died. "That ain't very smart", Young noted.Return to Earth

On the way back to Earth, Duke assisted in a deep-space EVA that lasted 1 hour and 23 minutes, when Mattingly climbed out of the ''Casper'' spacecraft and retrieved film cassettes from the service module. After a journey during which ''Casper'' had traveled , the Apollo 16 mission concluded with a

On the way back to Earth, Duke assisted in a deep-space EVA that lasted 1 hour and 23 minutes, when Mattingly climbed out of the ''Casper'' spacecraft and retrieved film cassettes from the service module. After a journey during which ''Casper'' had traveled , the Apollo 16 mission concluded with a splashdown

Splashdown is the method of landing a spacecraft by parachute in a body of water. It was used by crewed American space capsules prior to the Space Shuttle program, by SpaceX Dragon and Dragon 2 capsules and by NASA's Orion Multipurpose Crew ...

in the Pacific Ocean at 19:45:05 UTC on April 27, and recovery by the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

.

Duke left two items on the Moon, both of which he photographed. The most famous is a plastic-encased photo portrait of his family taken by NASA photographer Ludy Benjamin. The reverse of the photo was signed and thumb printed by Duke's family and bore this message: "This is the family of Astronaut Duke from Planet Earth, who landed on the Moon on the twentieth of April 1972."

The other item was a commemorative medal issued by the Air Force, which was celebrating its 25th anniversary in 1972. Duke was the only Air Force officer to visit the Moon that year. With the approval of the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

The chief of staff of the Air Force (acronym: CSAF, or AF/CC) is a statutory office () held by a general in the United States Air Force, and as such is the principal military advisor to the secretary of the Air Force on matter pertaining to th ...

, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

John D. Ryan John or Johnny Ryan may refer to:

Business

*John Ryan (businessman) (born 1950), pioneer of cosmetic surgery and chairman of Doncaster Rovers

*John D. Ryan (industrialist) (1864–1933), American copper mining magnate

*John Ryan (printer) (1761� ...

, and the Secretary of the Air Force

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

, Robert Seamans

Robert Channing Seamans Jr. (October 30, 1918 – June 28, 2008) was an MIT professor who served as NASA Deputy Administrator and 9th United States Secretary of the Air Force.

Birth and education

He was born in Salem, Massachusetts, to Pauline ...

, Duke took two silver medallions commemorating the anniversary. He left one on the Moon and donated the other to the Air Force. Today it is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base

Wright-Patterson Air Force Base (WPAFB) is a United States Air Force base and census-designated place just east of Dayton, Ohio, in Greene County, Ohio, Greene and Montgomery County, Ohio, Montgomery counties. It includes both Wright and Patte ...

in Dayton, Ohio

Dayton () is the sixth-largest city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Montgomery County. A small part of the city extends into Greene County. The 2020 U.S. census estimate put the city population at 137,644, while Greater Day ...

, along with a Moon rock from the Apollo 16 mission.

In the wake of the Apollo 15 postal covers scandal, Slayton replaced the Apollo 15 crew as the backup for the Apollo 17

Apollo 17 (December 7–19, 1972) was the final mission of NASA's Apollo program, the most recent time humans have set foot on the Moon or traveled beyond low Earth orbit. Commander Gene Cernan and Lunar Module Pilot Harrison Schmitt walked on ...

mission with the Apollo 16 one. Duke became the backup LMP, Young the backup commander, and Roosa the backup CMP. They went into training again in June 1972, just two months after Duke and Young had returned from the Moon. There was only a slim chance that they would be called upon to fly the mission, and in the event were not. Duke never flew in space again. He retired from NASA on January 1, 1976. He had spent 265 hours and 51 minutes in space.

Later life

Following his retirement from NASA, Duke left active duty in the USAF as a colonel, and entered theAir Force Reserve

The Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) is a MAJCOM, major command (MAJCOM) of the United States Air Force, with its headquarters at Robins Air Force Base, Georgia. It is the federal Air Reserve Component (ARC) of the U.S. Air Force, consisting of ...

. He served as Mobilization Augmentee to the Commander, Air Force Basic Military Training Center and to the Commander, USAF Recruiting Service. He graduated from the Industrial College of the Armed Forces in 1978 and was promoted to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

the following year. He retired in June 1986. He has logged 4,147 hours of flying time, of which 3,632 hours was in jet aircraft.

Duke had always been fond of Coors Beer, which was only available in Texas around Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

and El Paso

El Paso (; "the pass") is a city in and the seat of El Paso County in the western corner of the U.S. state of Texas. The 2020 population of the city from the U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the 23rd-largest city in the U.S., the s ...